Abstract

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) increases lipogenesis at the transcriptional level, and its expression is upregulated by liver X receptor α (LXRα). The LXRα/SREBP-1c signaling may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). We previously reported that a cholesterol metabolite, 5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfate (25HC3S), inhibits the LXRα signaling and reduces lipogenesis by decreasing SREBP-1c expression in primary hepatocytes. The present study aims to investigate the effects of 25HC3S on lipid homeostasis in diet-induced NAFLD mouse models. NAFLD was induced by feeding a high-fat diet (HFD) in C57BL/6J mice. The effects of 25HC3S on lipid homeostasis, inflammatory responses, and insulin sensitivity were evaluated after acute treatments or long-term treatments. Acute treatments with 25HC3S decreased serum lipid levels, and long-term treatments decreased hepatic lipid accumulation in the NAFLD mice. Gene expression analysis showed that 25HC3S significantly suppressed the SREBP-1c signaling pathway that was associated with the suppression of the key enzymes involved in lipogenesis: fatty acid synthase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, and glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase. In addition, 25HC3S significantly reduced HFD-induced hepatic inflammation as evidenced by decreasing tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 α/β mRNA levels. A glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test showed that 25HC3S administration improved HFD-induced insulin resistance. The present results indicate that 25HC3S as a potent endogenous regulator decreases lipogenesis, and oxysterol sulfation can be a key protective regulatory pathway against lipid accumulation and lipid-induced inflammation in vivo.

Introduction

The liver plays a pivotal role in maintenance of lipid homeostasis. Accumulation of lipids in liver tissue leads to nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD) (Clark et al., 2002). NAFLD affects 45% of the general population in the United States, with a prevalence of 60–95% in obese patients (Mazza et al., 2012). The spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple nonprogressive steatosis to progressive nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that results in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver. Hepatocyte lipotoxicity is a key histologic feature of NAFLD, and is correlated with progressive inflammation and fibrosis (Neuschwander-Tetri, 2010). The hallmark feature of NAFLD is the accumulation of fat in the form of neutral lipid droplets in hepatocytes (Tiniakos et al., 2010). To date, caloric restriction and aerobic exercise are the effective treatments of NAFLD, but they are difficult to achieve for most NAFLD patients. The most promising pharmacological treatment of NAFLD is the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonist that decreases lipid accumulation and attenuates inflammatory response in hepatocytes (Ahmed and Byrne, 2007). The results suggest that lowering hepatic lipid levels is a key factor in successful NAFLD therapy. Recently, sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) has been highly evaluated as a potential target for the treatment of NAFLD, based on its ability to control lipogenic gene expression and regulate fatty acid and triglyceride homeostasis (Horton et al., 2003; Goldstein et al., 2006; Ahmed and Byrne, 2007). Its role in de novo lipogenesis and NAFLD pathogenesis is fully justified (Grefhorst et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004). Thus, inhibition of the hepatic SREBP-1c signaling pathway could improve dyslipidemia and NAFLD.

Oxysterols can act at multiple points in cholesterol homeostasis and lipid metabolism (van Reyk et al., 2006; Gill et al., 2008; Javitt, 2008). The liver oxysterol receptor, or liver X receptor (LXR), is an oxysterol-regulated transcription factor in lipid metabolism (Chen et al., 2004; Cha and Repa, 2007). Activation of LXR limits cholesterol synthesis through degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, and stimulates cholesterol efflux and clearance through ATP-binding cassette, subfamily (ABC)A1 and ABCG5/8. However, activation of LXR upregulates the expression of SREBP-1c, which in turn regulates at least 32 genes involved in lipid biosynthesis and transport (Horton et al., 2002). Therefore, modulation of LXR activation by synthetic ligands could have a profound effect on serum cholesterol levels, but its inappropriate activation of SREBP-1c could lead to hepatic steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia due to the elevated fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis (Grefhorst et al., 2002). Hepatocytes have a limited capacity to store fatty acids in the form of triglycerides, and once overwhelmed, cell damage occurs (Reddy and Rao, 2006).

We have identified an endogenous sulfated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfate (25HC3S), which accumulates in hepatocyte nuclei after overexpression of the mitochondrial cholesterol delivery protein, StarD1 (Ren et al., 2006). 25HC3S is synthesized from 25-hydroxycholesrol (25HC) by sulfotransferase 2B1b, SULT2B1b, via oxysterol sulfation (Javitt et al., 2001; Fuda et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007). Overexpression of SULT2B1b inactivates the response of LXRα triggered by oxysterol and inhibits the expression of LXR target genes, including SREBP-1c and ABCA1. The oxysterol sulfation was believed to be an inactivation process (Chen et al., 2007). However, overexpression of SULT2B1b or addition of the sulfation product, 25HC3S, into cells decreases both SREBP-1c expression and processing, and suppresses the expression of key enzymes involved in lipid metabolism, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) and fatty acid synthase (FAS). Subsequently, it decreases intracellular neutral lipid and cholesterol accumulation (Ren et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010; Bai et al., 2011). These results indicate that oxysterol sulfation and its products may act as a cholesterol satiety signal that suppresses fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis via inhibition of the LXRα/SREBP-1c signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2008). These findings have been further addressed in vivo by overexpression of SULT2B1b in C57BL/6 and low-density lipoprotein receptor (−/−) [LDLR(−/−)] mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) or high-cholesterol diet (Bai et al., 2012). In the presence of 25HC, overexpression of SULT2B1b significantly increases sulfated oxysterols, especially 25HC3S, and thus decreases nuclear LXRα levels and the expression of SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS. As a result, overexpression of SULT2B1b in mice reduces lipid levels in sera and lipid accumulation in liver tissues (Bai et al., 2012). Furthermore, 25HC3S increases the expression of cytoplasmic IκBα levels in THP-1 microphages by activation of PPARγ. It reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced IκBα degradation, nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells (NFκB) nuclear translocation, and the expression and release of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). These results suggest that 25HC3S may act as an endogenous PPARγ ligand that suppresses inflammatory responses via the PPARγ/IκB/NFκB signaling pathway. In contrast, 25HC acts in an opposite manner by inducing IκBα degradation and nuclear NFκB accumulations (Xu et al., 2010, 2012). These findings indicate that oxysterol sulfation may also be involved in inflammatory responses, and may represent a novel regulatory pathway between lipid homeostasis and inflammatory responses.

In the present study, we demonstrate that acute treatments with 25HC3S substantially decrease serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels, and long-term treatments decrease lipid levels in liver tissues in NAFLD mouse models. The LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway as a potential molecular mechanism may be involved in 25HC3S administration. These findings provide strong evidence that the oxysterol sulfation product, 25HC3S, acts as a potent regulator involved in lipid metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Synthesis of 5-Cholesten-3β, 25-Diol 3-Sulfate.

A mixture of 25-hydroxycholesterol (6.5 mg, 0.016 mmol) and triethylamine-sulfur trioxide (3.5 mg, 0.019 mmol) was dissolved in dry pyridine (300 μl) and stirred at room temperature for 2 hours. The solvents were evaporated at 40°C under a nitrogen stream, and the syrup was added into 100 ml of alkalined CH3OH, pH 8.0. After the pellets were dissolved completely, the products were filtered and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a C18 column with a gradient elution system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). A binary system of solvent A [20% CH3CN in H2O (v/v)] and solvent B [20% CH3CN in CH3OH (v/v)] was used. It began at 50% A and 50% B with an initial flow rate of 1 ml/min for 10 minutes and increased to 100% B with a flow rate that was increased linearly to 2 ml/min over a 30-minute period, followed by an additional isocratic period of 20 minutes. 25HC3S was obtained as its sodium salt (4.7 mg, 57%) in white powder. The structure was characterized by mass spectrometry (Supplemental Fig. 1) and NMR spectroscopy analysis (Supplemental Fig. 2), as previously shown (Harney and Macrides, 2008; Ogawa et al., 2009).

Animal Studies.

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all applicable regulations. To examine the effect of 25HC3S on diet-induced lipid accumulation in sera and liver, 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were randomly assigned to two groups. The control group was fed a chow diet; the HFD group was fed HFD (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) containing 42% kcal from fat, 43% kcal from carbohydrate, 15% kcal from protein, and 0.2% cholesterol for 10 weeks. All mice were housed under identical conditions in an aseptic facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and given free access to water and food. At the end of the 10-week period, the mice (n = 10–17 in each treatment) were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle solution (ethanol/phosphate-buffered saline) or 25HC3S (25 mg/kg) twice and fasted overnight (14 hours) for acute treatments, or once every 3 days for 6 weeks and fasted 5 hours for long-term treatments. During the long-term treatments, the mice were continually fed with HFD, and their body mass and caloric intake were monitored every week. Blood samples were collected before sacrifice. Serum triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (CHOL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using standard enzymatic techniques in the clinical laboratory at McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Lipoprotein profiles in sera were analyzed by HPLC in the following descriptions.

HPLC Analysis of Serum Lipoprotein Profiles.

The lipoproteins of triglyceride and cholesterol in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) were measured by gel filtration using HPLC as previously described (Bai et al., 2012). Briefly, mouse serum (100 μl) was eluted with a solvent of 154 mM NaCl with 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min via a Pharmacia Superose 6 HR 10/30 fast protein liquid chromatography column (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA), and the signal was read at a wavelength of 280 nm. Fractions were collected for 1.2 minutes each from 20 minutes up to 100 minutes. A total of 180 μl of each fraction plus 20 μl of a 10× solution of Wako Total Cholesterol E Reagent (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA) was incubated in a 96-well plate at 37°C for 3 hours in the dark to analyze cholesterol level, and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 595 nm. Two microliters of each fraction plus 200 μl of Infinity Triglycerides Reagent (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was incubated in a 96-well plate at 37°C for 5 minutes in the dark to analyze triglyceride level, and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 500 nm. The lipoprotein profile was monitored as an internal control.

Histomorphology Analysis.

Three specimens from different regions of the liver of each mouse were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at room temperature overnight. The regions of the specimens were standardized for all mice. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 μm) were stained hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). 3-3′-Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen, and hematoxylin was used as the nuclear counterstain.

Quantification of Hepatic Lipids.

Liver tissues were homogenized, and the hepatic total lipids were extracted by a mixture of chloroform and methanol [2:1 (v/v)]. After the extracts were filtered, 0.2 ml of each was evaporated to dryness and dissolved in 100 μl of isopropanol containing 10% of Triton X-100 for the cholesterol assay (Wako Chemicals USA), 100 μl of the NEFA solution (0.5 g of EDTA-Na2, 2 g of Triton X-100, 0.76 ml of 1N NaOH, and 0.5 g of sodium azide/l, pH 6.5) for the free fatty acid assay (Wako Chemicals USA), or 100 μl of isopropanol only for the triglyceride assay (Fisher Scientific). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each lipid concentration was normalized by liver weight.

Western Blot Analysis of Special Protein in Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Extraction.

Liver tissues were homogenized, and cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from liver tissues were extracted by the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Fisher Scientific). The levels of expression of ACC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-30212), FAS (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; sc-55580), SREBP-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; sc-8984), and SREBP-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; sc-5603) were detected by the specific antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control for cytoplasmic fractions, and lamin B1 was used as a loading control for nuclear fractions. Each positive band was quantified by Advanced Image Data Analyzer (Aida, Straubenhardt, Germany).

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis.

The relative mRNA levels were measured by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction as previously described (Ren et al., 2004). Briefly, total RNA was isolated with an SV Total RNA Isolation Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) that included DNase treatment. Two micrograms of total RNA was used in the first-strand cDNA synthesis as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed using SYBR green (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) as an indicator in an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Amplifications of both β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were used as internal controls. Relative mRNA expression was quantified with the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method and expressed as 2-ΔΔCt. The sequences of primers were obtained from the Harvard Medical School PrimerBank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) and summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Insulin Sensitivity Analysis.

Glucose tolerance tests were performed by an intraperitoneal injection of D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a dose of 2 g/kg of body weight after an overnight (12-hour) fasting. Insulin tolerance tests were performed by an intraperitoneal injection of insulin (Novolin R; Novo Nordisk Inc., Princeton, NJ) at a dose of 0.5 U/kg of body weight after a 4-hour fasting. Blood samples were collected via the tail vein, and plasma glucose was monitored by a Precision Xtra Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., Alameda, CA).

Analysis of Hepatic Oxysterols and Oxysterol Sulfates by HPLC.

Mouse liver samples (400 mg) were digested by 2 mg/ml of proteinase K in phosphate-buffered saline (1 ml) at 50°C for 12 hours, and 40 ml of chloroform:methanol [2:1 (v/v)] was added to the digests. The mixture was sonicated for 30 minutes and filtered to remove insoluble materials. Then, 6 ml of water with 100 μl of 1 M K2CO3 was added into the mixture and shaken well before allowing it to stand for about 3 hours for phase separation.

The water/methanol phase that mainly contained sulfated oxysterols was evaporated under N2. The residues were resuspended in 20% methanol by sonication and passed through a Sep-Pak tC18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA). After the cartridge was washed by 20% methanol three times, the sulfated oxysterol fractions were eluted by 60% methanol and taken to dryness under an N2 stream below 40°C. The extracts were then solvolyzed in a mixture of acetone (1 ml), methanol (9 ml), and concentrated HCl (20 μl) at 39°C overnight. After the mixture was neutralized by 5% KOH in methanol, 30 μl of testosterone in chloroform solution (50 μg/ml) was added, and the whole mixture was evaporated to dryness. The residues were resuspended in 8 ml of hexane and loaded into a Waters Sep-Pak silica cartridge (400 mg) that had been prewashed with 2% isopropanol in hexane. The purified oxysterol fractions were finally eluted by 8 ml of isopropanol:hexane [1:9 (v/v)] and evaporated under N2.

The chloroform phase that mainly contains nonsulfated oxysterols was added to 30 μl of testosterone in chloroform solution (50 μg/ml) and evaporated under N2 below 40°C. The residue was resuspended in 8 ml of hexane and passed through a Waters Sep-Pak silica cartridge to purify the oxysterol fraction as described earlier.

Both the methanol/water phase and the chloroform phase hereby containing the oxysterols were derivatized to the corresponding 3-keto-Δ4 form with cholesterol oxidase essentially according to the reported method (Zhang et al., 2001), and were analyzed by the Water Alliance series 2695 HPLC module fitted with a 2487 Dual λ absorbance detector (Waters). The separation was carried out by an eluent of hexane:isopropanol:acetic acid [965:25:10 (v/v/v)] at a flow rate of 1.3 ml/min through an Ultrasphere silica column (5 μm, 4.6 mm i.d. × 250 mm; Beckman, Urbana, IL). The column temperature was kept constant at 30°C, and the enones were monitored at the absorption at 240 nm.

Statistical Analysis.

All results were expressed as the mean ± S.E. Western blot results were repeated at least three times. Statistical analysis was performed with Student t test for unpaired samples. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

25HC3S Administration Reduces Serum Lipid Levels in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet.

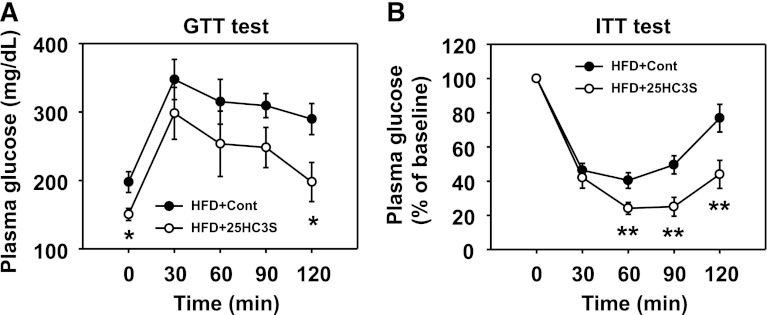

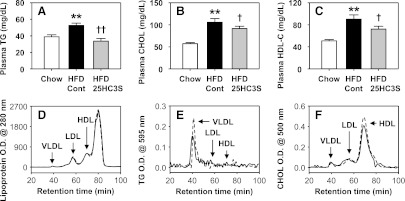

25HC3S has been shown to reduce lipid accumulation in both primary hepatocytes and THP-1 macrophages (Ren et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010). To investigate the effects of 25HC3S on hyperlipidemia in vivo, 8-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were fed an HFD to establish an NAFLD model, and mice were fed with chow diet as a negative control. After 10 weeks of feeding, the mice were treated with 25HC3S or vehicle twice in 14 hours and fasted overnight as acute treatments. Caloric intake and weight gain were similar in both treated groups. As expected, 10 weeks of feeding an HFD significantly elevated plasma TG, CHOL, and HDL-C by 1.4-fold, 1.9-fold, and 1.8-fold, respectively. In the HFD group, compared with the vehicle treatments, the acute treatments with 25HC3S significantly decreased plasma TG, CHOL, and HDL-C by 40, 15, and 20%, respectively (Fig. 1, A-C). The plasma triglyceride level was reduced to the same level as in healthy mice fed a chow diet (Fig. 1A). Liver function analysis showed that HFD raised serum ALT and AST levels, but there was no significant difference between 25HC3S-treated and vehicle-treated mice (data not shown), indicating acute administration of 25HC3S had no effect on liver function.

Fig. 1.

Effects of 25HC3S on serum lipid profiles in HFD-fed mice. Eight-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were fed an HFD or chow diet (Chow) for 10 weeks, treated with either 25HC3S or vehicle twice, and fasted overnight. Plasma triglyceride (A), total cholesterol (B), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (C) were determined. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. **P < 0.01 versus chow diet–fed vehicle-treated mouse liver; †P < 0.05 and ††P < 0.01 versus HFD-fed vehicle-treated mouse liver (n = 15–17). Serum lipoproteins were separated by HPLC with a Superose 6 column (D), and each fraction was collected for the measurement of concentration of triglycerides (E) and cholesterol (F). The data represent one of three separate experiments. Cont, vehicle control; O.D., optical density (absorbence).

The serum lipid profiles were further confirmed by HPLC analysis. Acute treatments with 25HC3S did not change LDL, VLDL, and HDL protein levels (Fig. 1D) but markedly decreased triglyceride contents in VLDL fractions and slightly decreased cholesterol contents in HDL fractions (Fig. 1, E and F), which is consistent with enzymatic analysis (Fig. 1, A-C). These results indicate that acute administration of 25HC3S significantly lowers serum lipid levels in the circulation in the NAFLD mouse model.

Analysis of 25HC3S in Liver Tissues.

To study the effects of 25HC3S on hepatic lipid metabolism in the mice fed an HFD, the concentration of 25HC3S in liver tissue from treated mice was determined by HPLC analysis. The results indicated that acute treatments of 25HC3S significantly increased its accumulation in the liver (Fig. 2). It was observed that a small peak of 25HC presented in the livers of 25HC3S-treated mice (Fig. 2), indicating that a small amount of 25HC3S was degraded to 25HC, where steroid sulfatase may be involved (Snyder et al., 2000).

Fig. 2.

HPLC analysis of 25HC3S and 25HC levels in treated mouse liver tissues. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 1. Total neutral lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol mixture and analyzed by HPLC. 24HC, 25HC, 27HC, and 7α-hydroxycholesterol (7α-HC) were used as standard controls; testosterone in the chloroform phase was used as an internal control. Oxysterols in the chloroform phase from vehicle- or 25HC3S-treated mouse liver were determined (left panel). Chemical synthesis of 25HC3S was used as a standard control in the water/methanol phase. 25HC3S levels in the water/methanol phase from vehicle- and 25HC3S-treated mouse liver were determined (right panel). The data represent one of three separate experiments.

Hepatic mRNA Expression in the 25HC3S-Treated Mice.

To compare the regulation of lipogenic gene expression in response to acute treatments of 25HC3S in the liver, we determined the mRNA expression by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction as shown in Table 1. Acute treatments with 25HC3S significantly suppressed the expression of the genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis. Compared with vehicle-treated mouse liver, 25HC3S reduced the mRNA levels of SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS by 46, 57, and 49%, respectively, which was consistent with previous in vitro results (Ren et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2010). However, there was no significant difference in the mRNA levels of PPARα, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1, acyl-CoA oxidase 1, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase between 25HC3S and vehicle treatment (Table 1). These results suggest that acute administration of 25HC3S lowers serum TG by inhibition of fatty acid synthesis but not stimulation of its oxidation. In addition, 25HC3S significantly suppressed ABCA1 expression, which may explain the lower level of plasma HDL cholesterol (Fig. 1, C and F).

TABLE 1.

Relative hepatic mRNA expression in mice fed an HFD with or without 25HC3S

Animals were treated as described in Fig. 1. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.D. (n = 5–6).

| Gene Name | Gene Description | HFD | HFD + 25HC3S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | |||

| SREBP-1c | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c | 1 ± 0.09 | 0.54 ± 0.13* |

| ACC1 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 | 1 ± 0.20 | 0.43 ± 0.12* |

| FAS | Fatty acid synthase | 1 ± 0.37 | 0.51 ± 0.37** |

| LXRα | Liver X receptor α | 1 ± 0.20 | 0.90 ± 0.42 |

| FABP1 | Fatty acid binding protein 1 | 1 ± 0.23 | 1.15 ± 0.46 |

| FATP1 | Fatty acid transport protein 1 | 1 ± 0.38 | 1.03 ± 0.28 |

| Fatty acid oxidation | |||

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α | 1 ± 0.37 | 0.95 ± 0.36 |

| CPT1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 | 1 ± 0.24 | 1.07 ± 0.19 |

| ACOX1 | Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 | 1 ± 0.23 | 0.79 ± 0.16 |

| MCAD | Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1 ± 0.19 | 1.30 ± 0.29 |

| SCAD | Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1 ± 0.21 | 0.95 ± 0.28 |

| Triglyceride metabolism | |||

| GPAM | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | 1 ± 0.22 | 1.06 ± 0.07 |

| MTTP | Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein | 1 ± 0.30 | 1.11 ± 0.17 |

| PLTP | Phospholipid transfer protein | 1 ± 0.17 | 0.96 ± 0.54 |

| Cholesterol metabolism | |||

| SREBP-2 | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 | 1 ± 0.30 | 1.07 ± 0.11 |

| HMGR | Hydroxy-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | 1 ± 0.41 | 0.94 ± 0.18 |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A1 | 1 ± 0.16 | 0.70 ± 0.12* |

| ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G1 | 1 ± 0.44 | 0.99 ± 0.65 |

| ABCG5 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G5 | 1 ± 0.15 | 0.99 ± 0.30 |

| CYP7α | Cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase | 1 ± 0.27 | 0.55 ± 0.17** |

| CYP27α | Mitochondrial cholesterol 27a-hydroxylase | 1 ± 0.12 | 1.06 ± 0.22 |

| Lipid uptake | |||

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor | 1 ± 0.43 | 0.91 ± 0.07 |

| CD36 | Thrombospondin receptor | 1 ± 0.27 | 0.93 ± 0.36 |

| SRB1 | Scavenger receptor class B, member 1 | 1 ± 0.12 | 1.25 ± 0.22 |

| Inflammatory response | |||

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ | 1 ± 0.23 | 1.63 ± 0.41** |

| IκBα | Nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor α | 1 ± 0.20 | 1.04 ± 0.14 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor α | 1 ± 0.21 | 0.65 ± 0.28** |

| NFκB (Rela) | V-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A | 1 ± 0.22 | 0.83 ± 0.19 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin 1α | 1 ± 0.29 | 0.92 ± 0.23 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β | 1 ± 0.78 | 1.11 ± 0.64 |

| Glucose metabolism | |||

| G6Pase | Glucose-6-phosphatase | 1 ± 0.23 | 1.23 ± 0.70 |

| PCK1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | 1 ± 0.20 | 1.07 ± 0.26 |

| GCK | Glucokinase | 1 ± 0.21 | 1.21 ± 0.75 |

| Pklr | Pyruvate kinase, liver and red blood cell | 1 ± 0.22 | 0.56 ± 0.16* |

25HC3S, 5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfate; HFD, high-fat diet.

P < 0.01 and **P < 0.05 compared with HFD mice.

25HC3S Administration Decreases Nuclear SREBP-1 Protein Levels and Cytoplasmic FAS and ACC1 Protein levels in Liver Tissue.

SREBP-1c upregulates fatty acid and triglyceride biosynthesis by binding with SREBP-1 response elements and increasing expression of rate-limiting enzymes, including FAS and ACC1. To determine if 25HC3S inactivated the SREBP-1c pathway, nuclear SREBP-1 protein levels in liver tissues were determined by Western blot analysis. Interestingly, HFD feeding markedly increased the nuclear SREBP-1 mature form and induced its target-gene ACC1 expression (unpublished data). 25HC3S significantly suppressed nuclear SREBP-1, cytoplasmic ACC1, and FAS protein levels by 74, 58, and 47%, respectively (Fig. 3), which is consistent with mRNA levels as shown in Table 1. These results suggest that acute administration of 25HC3S suppresses lipogenesis by inhibition of the SREBP-1c signaling pathway.

Fig. 3.

The effects of 25HC3S on protein expressions in lipid metabolism in liver tissues. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 1. Specific protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were determined by Western blot analysis. Cytoplasmic ACC1 and FAS protein levels are shown in (A), normalized by β-actin, and nuclear SREBP1 and SREBP2 are shown in (B), normalized by lamin B1. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05 versus HFD-fed vehicle-treated mouse liver (n = 6–8). CONT, vehicle control.

Effects of Long-Term Treatments of 25HC3S on Lipid Homeostasis in HFD-Fed Mice.

To study the effects of long-term treatments of 25HC3S on lipid homeostasis, 8-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were fed an HFD for 10 weeks, and were then divided into two groups. One was treated with 25HC3S by peritoneal injection once every 3 days for 6 weeks, and the other was treated with vehicle under the same conditions. During the treatments, the mice were continuously fed an HFD. Body mass and caloric intakes were monitored every week. The body mass of 25HC3S-treated mice increased significantly slower than the control mice, but there was no significant difference in the caloric intake between these two groups (Fig. 4, A and B). After the 6-week injection, the mice were fasted for 5 hours before sacrifice. The average liver weight was significantly decreased in the 25HC3S-treated group (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The effects of long term-treatment with 25HC3S on mouse body mass and food intake. C57BL/6J female mice were fed an HFD, separated into two groups, and treated with either 25HC3S or vehicle once every 3 days for 6 weeks. During these 6 weeks, total food intake (A) and body weight (B) were monitored. After 5 hours of fasting, liver weight was determined (C), as were plasma alkaline phosphatase (ALK) (D), ALT (E), and AST (F). All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 10). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus HFD-fed vehicle-treated mouse liver. CONT, vehicle control; CT, control vehicle treatment.

As expected, 25HC3S significantly decreased plasma cholesterol levels as compared with vehicle-treated mice, but surprisingly, 25HC3S did not significantly decrease plasma TG levels (unpublished data). The liver function analysis indicated that 25HC3S treatment significantly reduced serum alkaline phosphatase, ALT, and AST levels (Fig. 4, D-F). These results indicate that 25HC3S treatment protects the liver from injury, possibly by suppressing hepatic inflammation.

To study the effect of 25HC3S on hepatic lipid metabolism, we measured hepatic lipid level and gene expression. As expected, HFD feeding in mice significantly increased triglyceride, total cholesterol, free cholesterol, and free fatty acid levels in the liver by 3-, 3.5-, 3.2-, and 2.5-fold compared with chow diet feeding (P < 0.01). However, long-term treatments with 25HC3S significantly reduced these levels by 30, 15, 28, and 23%, respectively (Fig. 5, A-D). Cholesterol ester concentration was not affected by the administration of 25HC3S (Fig. 5E). The decreases in lipid levels were further confirmed by morphologic analysis (Fig. 5F). Livers from the mice fed an HFD were pale and were distended by large cytoplasmic lipid inclusions compared with the livers from the mice fed a chow diet, suggesting the NAFLD model was successfully established following HFD feeding. Long-term treatments with 25HC3S significantly decreased lipid inclusions in hepatocytes.

Fig. 5.

Long-term treatment with 25HC3S decreases lipid accumulation in liver tissue in mouse NAFLD models. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 4. Hepatic triglyceride (A), free fatty acid (B), total cholesterol (C), free cholesterol (D), and cholesterol ester (E) are shown. Each individual level was normalized by liver weight. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.D. #P < 0.001 versus chow-fed vehicle-treated mice; **P < 0.01 versus HFD-fed vehicle-treated mouse liver. In a morphology study, liver sections from chow diet–fed (chow), HFD-fed, and HFD-fed and 25HC3S-treated (HFD-25HC3S) mice were stained by H&E staining (F). Arrows indicate unstained lipid inclusions. CT, control vehicle treatment.

Gene expression analysis showed that long-term treatments with 25HC3S significantly decreased mRNA levels of SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS by 23, 41, and 27%, respectively (Table 2), which is consistent with the acute treatments (Table 1). More interestingly, long-term treatments with 25HC3S significantly decreased the expression of the key enzymes involved in triglyceride synthesis, glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAM), by 21%, as well as lipid transfer proteins, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP), by 23 and 39%, respectively. In addition, long-term treatments with 25HC3S decreased the expression of the genes involved in oxidized LDL uptake, CD36 and scavenger receptor class B, member 1, by 48 and 21%, respectively. Both genes are known to contribute to the development of foam cells (Abumrad and Davidson, 2012), but CD36 is also known to be involved in hepatic inflammation (Bieghs et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012).

TABLE 2.

Relative hepatic mRNA expression in mice fed an HFD with or without 25HC3S

Animals were treated as described in Fig. 4. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.D. (n = 5–6).

| Gene Name | Gene Description | HFD | HFD + 25HC3S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | |||

| SREBP-1c | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c | 1 ± 0.12 | 0.77 ± 0.06* |

| ACC1 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 | 1 ± 0.33 | 0.59 ± 0.05* |

| FAS | Fatty acid synthase | 1 ± 0.47 | 0.73 ± 0.07* |

| LXRα | Liver X receptor α | 1 ± 0.27 | 1.07 ± 0.45 |

| FABP1 | Fatty acid binding protein 1 | 1 ± 0.36 | 0.98 ± 0.41 |

| FATP1 | Fatty acid transport protein 1 | 1 ± 0.53 | 0.69 ± 0.25 |

| Fatty acid oxidation | |||

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α | 1 ± 0.16 | 0.81 ± 0.18 |

| CPT1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 | 1 ± 0.16 | 0.79 ± 0.11* |

| ACOX1 | Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 | 1 ± 0.21 | 0.95 ± 0.14 |

| MCAD | Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.15* |

| SCAD | Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1 ± 0.12 | 0.95 ± 0.14 |

| Triglyceride metabolism | |||

| GPAM | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | 1 ± 0.21 | 0.79 ± 0.08* |

| MTTP | Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein | 1 ± 0.22 | 0.77 ± 0.07* |

| PLTP | Phospholipid transfer protein | 1 ± 0.43 | 0.61 ± 0.07* |

| Cholesterol metabolism | |||

| SREBP-2 | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 | 1 ± 0.26 | 1.07 ± 0.31 |

| HMGR | Hydroxy-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | 1 ± 0.09 | 1.19 ± 0.22 |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A | 1 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.10* |

| ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G | 1 ± 0.24 | 0.66 ± 0.13* |

| CYP7α | Cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase | 1 ± 0.59 | 0.68 ± 0.34 |

| CYP27α | Mitochondrial cholesterol 27a-hydroxylase | 1 ± 0.17 | 0.91 ± .15 |

| Lipid uptake | |||

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor | 1 ± 0.39 | 0.80 ± 0.21 |

| CD36 | Thrombospondin receptor | 1 ± 0.24 | 0.52 ± 0.04** |

| SRB1 | Scavenger receptor class B, member 1 | 1 ± 0.17 | 0.79 ± 0.06* |

| Inflammatory response | |||

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ | 1 ± 0.23 | 0.78 ± 0.21 |

| IκBα | Νuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor α | 1 ± 0.31 | 1.11 ± 0.66 |

| NFκB (Rela) | V-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A | 1 ± 0.33 | 1.00 ± 0.48 |

| TNFα | Τumor necrosis factor α | 1 ± 0.20 | 0.53 ± 0.18* |

| IL-1α | Interleukin 1α | 1 ± 0.30 | 0.52 ± 0.07* |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β | 1 ± 0.49 | 0.50 ± 0.14* |

| Glucose metabolism | |||

| G6Pase | Glucose-6-phosphatase | 1 ± 0.31 | 1.05 ± 0.44 |

| PCK1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | 1 ± 0.20 | 1.30 ± 0.99 |

| GCK | Glucokinase | 1 ± 0.30 | 1.19 ± 0.67 |

| Pklr | Pyruvate kinase, liver and red blood cell | 1 ± 0.17 | 0.97 ± 0.17 |

25HC3S, 5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfate; HFD, high-fat diet.

P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with HFD mice.

Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is frequently associated with inflammatory conditions. Elevated circulating free fatty acid (FFA) may be directly cytotoxic to the liver by stimulating TNFα expression via a lysosomal pathway, activating mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and oxidative stress (Feldstein et al., 2004; Malhi et al., 2006). Thus, it was of interest to investigate the effect of 25HC3S on hepatic inflammatory response. Long-term treatments with 25HC3S significantly suppressed the mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines, TNFα, IL-1α, and IL-1β, by 47, 48, and 50%, respectively (Table 2). A similar effect has been observed in the acute treatments with 25HC3S, where the mRNA expression of TNFα was decreased by 35% (Table 1). These results are consistent with the liver function assay, which showed that 25HC3S suppresses liver inflammatory responses and prevents liver damage (Fig. 4, E and F).

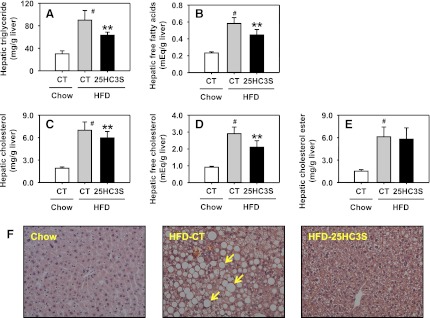

Under the condition of metabolic disorders, lipid accumulation in the liver is always associated with the development of insulin resistance. As reported, HFD feeding significantly elevated fasting glucose and insulin levels in mice compared with chow diet feeding (Li et al., 2010). To study the effect of 25HC3S on glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity, a glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test were performed after long-term treatments with 25HC3S. As shown in Fig. 6A, administration of 25HC3S significantly decreased fasting glucose levels and improved insulin sensitivity (Fig. 6B), suggesting that repression of lipid accumulation in the liver and circulation by 25HC3S administration improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in HFD-fed mice.

Fig. 6.

Long-term treatment with 25HC3S improved insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis in HFD-fed mice. Animals were treated as described in Fig. 4. GTT (A) and ITT (B) were performed. All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 9–10). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus HFD-fed vehicle-treated mice. Cont, control vehicle; GTT, glucose tolerance test; ITT, insulin tolerance test.

Discussion

The liver is a key metabolic organ that responds to the imbalance of high-caloric diets, especially HFD, and it plays a central role in lipid homeostasis (Canbay et al., 2007). Due to HFD consumption or obesity, plasma FFA levels are elevated, which induces intrahepatocellular accumulation of triglycerides and diacylglycerol, and produces low-grade inflammation in the liver through activation of NFκB, resulting in the release of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6. Lipotoxicity induced by elevated FFA increases oxidative stress and causes insulin resistance in muscle, liver, and endothelial cells. Excess FFA contributes to the accumulation of lipid droplets in hepatocytes, which becomes the hallmark of liver diseases such as dyslipidemia, NAFLD, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Boden, 2006; Malhi and Gores, 2008). The pathogenesis of NAFLD is complex, but the transcription factors of hepatic lipid and glucose homeostasis may be a key to treating NAFLD. As a key transcription factor regulating hepatic fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis, SREBP-1c activity modulation has been evaluated as a potential new treatment of NAFLD (Ahmed and Byrne, 2007; Vallim and Salter, 2010).

LXRs are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcriptional factors involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism and inflammatory process (Torocsik et al., 2009). Administration of the LXR agonist to mice induces a mild and transient hypertriglyceridemia and hepatic steatosis. The molecular mechanism for this is that LXRs activate triglyceride synthesis in the liver directly and indirectly by inducing SREBP-1c expression (Chen et al., 2004; Okazaki et al., 2010). In our previous studies, we identified a cholesterol metabolite, 25HC3S, in primary hepatocytes overexpressing StarD1 (Ren et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). When intracellular cholesterol levels are increased, StarD1 delivers cholesterol into mitochondria, where regulatory oxysterols, such as 25HC, are synthesized by CYP27α1 (Li et al., 2006, 2007). These oxysterols can activate LXRα and then upregulate the expression of SREBP-1c, which induces hepatic lipogenesis (Ferber, 2000; Gill et al., 2008). 25HC can further be sulfated in the cytoplasm by SULT2B1b to 25HC3S when delivery of cholesterol to the mitochondria is increased (Ren et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). 25HC3S in turn inactivates LXRα, suppresses SREBP-1c expression, and subsequently decreases intracellular lipid levels (Ren et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010). In our recent report, in vivo, overexpression of SULT2B1b significantly increased 25HC3S formation in the liver and lowered lipid levels in the serum and in the liver by inhibition of the LXRα/SREBP-1c signaling pathway in mice fed an HFD. This was observed in the presence of 25HC, but not in the absence of 25HC. The same effects were also observed in LDLR knockout mice, indicating that SULT2B1b reduced serum and hepatic lipid levels due to the suppression of lipid biosynthesis rather than clearance.

In the current study, we provide the first evidence for the effect of 25HC3S on HFD-induced NAFLD models in vivo. 25HC3S not only reduced HFD-induced lipid accumulation in serum and liver, but also suppressed HFD-induced hepatic inflammation and insulin resistance. Since several mechanisms could account for the protective effect of 25HC3S in this model, to seek an explanation, we analyzed the expression of different genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, fatty acid β-oxidation, triglyceride synthesis, cholesterol metabolism, and lipid clearance. Interestingly, administration of 25HC3S to the mice significantly suppressed fatty acid synthesis by suppressing SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS expression, but had little effect on fatty acid β-oxidation (Tables 1 and 2). As reported, HFD feeding markedly induces the expression of SREBP-1c in wild-type mice (Li et al., 2010). Four SREBP-1c target genes, ACC1, FAS, GPAM, and PLTP, have been identified following administration of the LXR agonist T0901317 to wild-type, LRLR−/− and LDLR−/−, SREBP-1c−/− mice (Okazaki et al., 2010). Among these, the most likely candidate genes involved in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis are ACC1, FAS, and GPAM. PLTP has been found to increase hepatic VLDL secretion (Jiang et al., 2001). Together, HFD activates the LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway and increases large VLDL particles via two processes. One is the increase in triglyceride production by activation of fatty acid and triglyceride biosynthesis, and the other is the increase in triglyceride loading in VLDL particles by upregulation of PLTP to insert additional phospholipids into the particles (Okazaki et al., 2010). Our current data in mice suggest that the reduction of serum triglyceride (Fig. 1A), especially in VLDL particles (Fig. 1E), by administration of 25HC3S may be due to both processes: the decrease in lipogenesis by suppression of ACC1, FAS, and GPAM (Tables 1 and 2), and the decrease in VLDL particle assembly by suppression of PLTP (Table 2). These results indicate that the inhibition of the LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway may be involved in 25HC3S-treated mice. In addition, ABCA1, ABCG1, ABCG5, and CYP7α have been reported as the other LXR targets involved in cholesterol clearance (Ando et al., 2005; Baldan et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010). Our current data show the administration of 25HC3S in mice suppressed the mRNA expression of ABCA1, ABCG1, and CYP7α, and led to a decrease in cholesterol efflux (Tables 1 and 2). As a result, 25HC3S treatment in mice reduced cholesterol levels in HDL particles (Fig. 1, C–F). In our previous report, 25HC3S inhibits the LXR response element (LXRE)-luciferase reporter gene expression induced by 25HC or LXR agonist T0901317 in H441 cells transfected with either LXRα or LXRβ recombinant plasmid (Ma et al., 2008). However, LXRα and LXRβ have overlapping but discrete functions. LXRβ has been reported as a major regulator of glucose homeogenesis, energy utilization, and fat storage in muscle and white adipose tissue (Korach-Andre et al., 2010; Polyzos et al., 2012). The present data further support that 25HC3S serves as an endogenous LXR antagonist, suppressing LXR target gene expression in vivo.

The progression of NAFLD to NASH is characterized by hepatocyte lipotoxicity. Several studies have demonstrated a major contribution of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6, to the progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis (Neuschwander-Tetri, 2010; Tilg and Moschen, 2010). Levels of these proinflammatory cytokines correlate with the stage of fibrosis and with the NAFLD activity score in NASH (Manco et al., 2007). In our previous report, 25HC3S significantly suppressed TNFα-induced inflammatory response in HepG2 cells and lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in THP-1 microphages (Xu et al., 2010, 2012). Addition of 25HC3S to human macrophages markedly increased nuclear PPARγ, cytosol IκBα, and decreased nuclear NFκB protein levels. 25HC3S significantly increased PPARγ-luciferase report gene expression. The Ki for 25HC3S was ∼1 μM, similar to other PPARγ ligands in PPARγ-competitor assay, suggesting this effect is via the PPARγ/IκBα signaling pathway (Xu et al., 2012). In the present study, we also observed that administration of 25HC3S to the mice significantly suppressed hepatic mRNA expression of TNFα (Tables 1 and 2) and IL-1α/β (Table 2). Subsequently, it reduced liver damage by the decrease in serum ALT and AST levels (Fig. 4, E and F). Interestingly, we did not observe a significant increase in the mRNA expression of IκBα in the liver by 25HC3S administration as we previously showed in vitro (Xu et al., 2010).

Due to the excess FFA, the development of NAFLD and NASH not only causes ectopic fat accumulation in the liver, but also raises insulin resistance in adipose tissue (Cusi, 2012; Samuel and Shulman, 2012). Our preliminary studies suggest that the suppression of lipogenesis by 25HC3S administration in mice leads to a decrease in ectopic lipid droplet accumulation in hepatocytes (Fig. 5). Ultimately, it led to improved insulin signaling and reduced insulin resistance (Fig. 6).

Dietary cholesterol such as in an HFD or high-cholesterol diet induces hepatic cholesterol ester and triglyceride accumulation in liver tissues. The excess cholesterol is metabolized to oxysterols such as 25HC, 27HC, and 24-(S), 25-epoxycholesterol, and in turn activates LXR (Basciano et al., 2009). These oxysterols may be surrogate markers of insulin resistance, and the high oxysterol levels in the circulation play an important role in the development of hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance followed by NAFLD (Ikegami et al., 2012). The present study shows that 25HC3S as a potent endogenous regulator has a beneficial effect on dyslipidemia and the early stage of NAFLD, and oxysterol sulfation is another novel systematic regulatory pathway involved in regulating lipid and glucose homeostasis and inflammatory response. These results indicate that 25HC3S decreases lipogenesis by inhibiting the SREBP-1c signaling pathway in vivo. Oxysterol sulfation can be a key protective regulatory pathway against lipid accumulation and lipid-induced inflammation in the liver (Cha and Kim, 2012; Polyzos et al., 2012). There are 48 and 49 nuclear receptors identified in humans and mice, respectively, including classic steroid hormone receptors, orphan receptors, and adopted orphan receptors. Many of them are involved in lipid metabolism, and their ligands are believed to be lipid derivatives. Current results indicate that 25HC3S decreases lipogenesis, most likely via inhibiting the LXRα/SREBP-1c signaling pathway in vivo. However, the detailed mechanism of the molecular-molecular interaction needs further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical help from Patricia Cooper, Dalila Marques, and Kaye Redford.

Abbreviations

- ABCA(G)

ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A(G)

- ACC1

acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CHOL

total cholesterol

- CYP27α1

mitochondrial cholesterol 27α-hydroxylase

- CYP7α1

cholesterol 7α -hydroxylase

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- FFA

free fatty acid

- GPAM

glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase

- 25HC

25-hydroxycholesterol

- 25HC3S

5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfate

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IκBα

nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, α

- IL

interleukin

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LXR

liver X receptor

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonaclcoholic steatohepatitis

- NFκB

nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells

- PLTP

phospholipid transfer protein

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SREBP

sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- SULT2B1b

sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 2B, member 1b

- TG

triglyceride

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- VLDL

very-low-density lipoprotein

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Xu, Ren.

Conducted experiments: Xu, Kim, Bai, Zhang, Kakiyama.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Xu, Kakiyama.

Performed data analysis: Xu, Ren.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Xu, Min, Sanyal, Pandak, Ren.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant 5R01HL078898]; and the VA Merit Review [Program Number 821, Cost Center 103] from the Veterans Affairs Administration.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abumrad NA, Davidson NO. (2012) Role of the gut in lipid homeostasis. Physiol Rev 92:1061–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MH, Byrne CD. (2007) Modulation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) as potential treatments for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Drug Discov Today 12:740–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H, Tsuruoka S, Yamamoto H, Takamura T, Kaneko S, Fujimura A. (2005) Regulation of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase mRNA expression in C57BL/6 mice fed an atherogenic diet. Atherosclerosis 178:265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q, Xu L, Kakiyama G, Runge-Morris MA, Hylemon PB, Yin L, Pandak WM, Ren S. (2011) Sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol by SULT2B1b decreases cellular lipids via the LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway in human aortic endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 214:350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q, Zhang X, Xu L, Kakiyama G, Heuman D, Sanyal A, Pandak WM, Yin L, Xie W, Ren S. (2012) Oxysterol sulfation by cytosolic sulfotransferase suppresses liver X receptor/sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c signaling pathway and reduces serum and hepatic lipids in mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 61:836–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldán A, Bojanic DD, Edwards PA. (2009) The ABCs of sterol transport. J Lipid Res 50 (Suppl):S80–S85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basciano H, Miller AE, Naples M, Baker C, Kohen R, Xu E, Su Q, Allister EM, Wheeler MB, Adeli K. (2009) Metabolic effects of dietary cholesterol in an animal model of insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297:E462–E473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieghs V, van Gorp PJ, Walenbergh SM, Gijbels MJ, Verheyen F, Buurman WA, Briles DE, Hofker MH, Binder CJ, Shiri-Sverdlov R. (2012) Specific immunization strategies against oxidized low-density lipoprotein: a novel way to reduce nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 56:894–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G. (2006) Fatty acid-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and liver. Curr Diab Rep 6:177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canbay A, Bechmann L, Gerken G. (2007) Lipid metabolism in the liver. Z Gastroenterol 45:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JY, Kim YB. (2012) Sulfated oxysterol 25HC3S as a therapeutic target of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 61:1055–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JY, Repa JJ. (2007) The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J Biol Chem 282:743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Liang G, Ou J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. (2004) Central role for liver X receptor in insulin-mediated activation of Srebp-1c transcription and stimulation of fatty acid synthesis in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11245–11250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chen G, Head DL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Russell DW. (2007) Enzymatic reduction of oxysterols impairs LXR signaling in cultured cells and the livers of mice. Cell Metab 5:73–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. (2002) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 122:1649–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusi K. (2012) Role of obesity and lipotoxicity in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Gastroenterology 142:711–725, e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. (2004) Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology 40:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber D. (2000) Lipid research. Possible new way to lower cholesterol. Science 289:1446–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuda H, Javitt NB, Mitamura K, Ikegawa S, Strott CA. (2007) Oxysterols are substrates for cholesterol sulfotransferase. J Lipid Res 48:1343–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S, Chow R, Brown AJ. (2008) Sterol regulators of cholesterol homeostasis and beyond: the oxysterol hypothesis revisited and revised. Prog Lipid Res 47:391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. (2006) Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell 124:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefhorst A, Elzinga BM, Voshol PJ, Plösch T, Kok T, Bloks VW, van der Sluijs FH, Havekes LM, Romijn JA, Verkade HJ, et al. (2002) Stimulation of lipogenesis by pharmacological activation of the liver X receptor leads to production of large, triglyceride-rich very low density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem 277:34182–34190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney DW, Macrides TA. (2008) Synthesis of an isomeric mixture (24RS,25RS) of sodium scymnol sulfate. Steroids 73:424–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. (2002) SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest 109:1125–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, Anderson NN, Park SW, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. (2003) Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:12027–12032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T, Hyogo H, Honda A, Miyazaki T, Tokushige K, Hashimoto E, Inui K, Matsuzaki Y and Tazuma S (2012) Increased serum liver X receptor ligand oxysterols in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol 47:1257–1266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Javitt NB. (2008) Oxysterols: novel biologic roles for the 21st century. Steroids 73:149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt NB, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Fuda H, Strott CA. (2001) Cholesterol and hydroxycholesterol sulfotransferases: identification, distinction from dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase, and differential tissue expression. Endocrinology 142:2978–2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XC, Qin S, Qiao C, Kawano K, Lin M, Skold A, Xiao X, Tall AR. (2001) Apolipoprotein B secretion and atherosclerosis are decreased in mice with phospholipid-transfer protein deficiency. Nat Med 7:847–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korach-André M, Parini P, Larsson L, Arner A, Steffensen KR, Gustafsson JA. (2010) Separate and overlapping metabolic functions of LXRalpha and LXRbeta in C57Bl/6 female mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298:E167–E178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Viswanadha S, Loor JJ. (2012) Hepatic Metabolic, Inflammatory, and Stress-Related Gene Expression in Growing Mice Consuming a Low Dose of Trans-10, cis-12-Conjugated Linoleic Acid. J Lipids 2012:571281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Owsley E, Matozel M, Hsu P, Novak CM, Chiang JY. (2010) Transgenic expression of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase in the liver prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 52:678–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Hylemon P, Pandak WM, Ren S. (2006) Enzyme activity assay for cholesterol 27-hydroxylase in mitochondria. J Lipid Res 47:1507–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Pandak WM, Erickson SK, Ma Y, Yin L, Hylemon P, Ren S. (2007) Biosynthesis of the regulatory oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3beta,25-diol 3-sulfate, in hepatocytes. J Lipid Res 48:2587–2596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Xu L, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Li X, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Pandak WM, Ren S. (2008) 25-Hydroxycholesterol-3-sulfate regulates macrophage lipid metabolism via the LXR/SREBP-1 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295:E1369–E1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi H, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Gores GJ. (2006) Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem 281:12093–12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi H, Gores GJ. (2008) Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 28:360–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manco M, Marcellini M, Giannone G, Nobili V. (2007) Correlation of serum TNF-alpha levels and histologic liver injury scores in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Pathol 127:954–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza A, Fruci B, Garinis GA, Giuliano S, Malaguarnera R, Belfiore A. (2012) The role of metformin in the management of NAFLD. Exp Diabetes Res 2012:716404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA. (2010) Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology 52:774–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Kakiyama G, Muto A, Hosoda A, Mitamura K, Ikegawa S, Hofmann AF, Iida T. (2009) A facile synthesis of C-24 and C-25 oxysterols by in situ generated ethyl(trifluoromethyl)dioxirane. Steroids 74:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki H, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Liang G. (2010) LXR-SREBP-1c-phospholipid transfer protein axis controls very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) particle size. J Biol Chem 285:6801–6810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. (2012) Sulfated oxysterols as candidates for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 61:755–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy JK, Rao MS. (2006) Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290:G852–G858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Hylemon P, Marques D, Hall E, Redford K, Gil G, Pandak WM. (2004) Effect of increasing the expression of cholesterol transporters (StAR, MLN64, and SCP-2) on bile acid synthesis. J Lipid Res 45:2123–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Hylemon P, Zhang ZP, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Marques D, Li X, Zhou H, Gil G, Pandak WM. (2006) Identification of a novel sulfonated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3beta,25-diol 3-sulfonate, in hepatocyte nuclei and mitochondria. J Lipid Res 47:1081–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Li X, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Gil G, Hylemon P, Pandak WM. (2007) Sulfated oxysterol, 25HC3S, is a potent regulator of lipid metabolism in human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 360:802–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel VT, Shulman GI. (2012) Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell 148:852–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder VL, Turner M, Li PK, El-Sharkawy A, Dunphy G, Ely DL. (2000) Tissue steroid sulfatase levels, testosterone and blood pressure. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 73:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. (2010) Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 52:1836–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiniakos DG, Vos MB, Brunt EM. (2010) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol 5:145–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töröcsik D, Szanto A, Nagy L. (2009) Oxysterol signaling links cholesterol metabolism and inflammation via the liver X receptor in macrophages. Mol Aspects Med 30:134–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallim T, Salter AM. (2010) Regulation of hepatic gene expression by saturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 82:211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Reyk DM, Brown AJ, Hult’en LM, Dean RT, Jessup W. (2006) Oxysterols in biological systems: sources, metabolism and pathophysiological relevance. Redox Rep 11:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Bai Q, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Hylemon PB, Heuman DM, Pandak WM, Ren S. (2010) Regulation of hepatocyte lipid metabolism and inflammatory response by 25-hydroxycholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol-3-sulfate. Lipids 45:821–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Shen S, Ma Y, Kim JK, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Pandak WM, Ren S. (2012) 25-Hydroxycholesterol-3-sulfate attenuates inflammatory response via PPARγ signaling in human THP-1 macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302:E788–E799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li D, Blanchard DE, Lear SR, Erickson SK, Spencer TA. (2001) Key regulatory oxysterols in liver: analysis as delta4-3-ketone derivatives by HPLC and response to physiological perturbations. J Lipid Res 42:649–658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.