Abstract

Smoothened (Smo) is a 7-transmembrane protein essential to the activation of Gli transcription factors (Gli) by hedgehog morphogens. The structure of Smo implies interactions with heterotrimeric G proteins, but the degree to which G proteins participate in the actions of hedgehogs remains controversial. We posit that the Gi family of G proteins provides to hedgehogs the ability to expand well beyond the bounds of Gli. In this regard, we evaluate here the efficacy of Smo as it relates to the activation of Gi, by comparing Smo with the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A (5-HT1A) receptor, a quintessential Gi-coupled receptor. We find that with use of [35S]guanosine 5′-(3-O-thio)triphosphate, first, with forms of Gi endogenous to human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells made to express epitope-tagged receptors and, second, with individual forms of Gαi fused to the C terminus of each receptor, Smo is equivalent to the 5-HT1A receptor in the assay as it relates to capacity to activate Gi. This finding is true regardless of subtype of Gi (e.g., Gi2, Go, and Gz) tested. We also find that Smo endogenous to HEK-293 cells, ostensibly through inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, decreases intracellular levels of cAMP. The results indicate that Smo is a receptor that can engage not only Gli but also other more immediate effectors.

Introduction

Smoothened (Smo) is a 7-transmembrane protein essential to most of the actions of the hedgehog family of morphogens (Jiang and Hui, 2008; Wilson and Chuang, 2010). When derepressed through binding of hedgehogs to patched1 (Ptch1), Smo engages a series of proteins that lead to stabilization of the Gli2 and Gli3 zinc-finger transcription factors and to subsequent expression of Gli1. Consequent derepression and/or frank activation of diverse sets of genes leads to cell type–dependent programs of response.

Efforts to understand the means by which Smo stabilizes the Gli transcription factors (Gli) have focused mostly on transport of Smo to the primary cilium and subsequent forms of scaffolding (Wilson and Chuang, 2010). However, the structure of Smo is that of a G protein–coupled receptor, suggesting interactions with heterotrimeric G proteins and, thus, additional forms of transduction. We determined that Smo indeed activates members of the Gi family of G proteins (i.e., Gi, Go, and Gz) (Riobo et al., 2006). We also determined that Gi is required in the activation of Gli in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. The data are in accord with the effects of a Bordetella pertussis toxin (Ptx) on selected aspects of eye, brain, and somite patterning in zebrafish (Hammerschmidt and McMahon, 1998) and the effects of dsRNA-mediated knockdown of Gαi in Drosophila on the activation of Cubitus interruptus, a Gli homolog (Ogden et al., 2008). The requirement for Gi in the activation of Gli is, however, not universal. Ptx has no impact on Gli-dependent patterning events in zebrafish beyond those noted above, nor does it have an impact on Gli-dependent chick neural tube patterning (Low et al., 2008).

The question of a role for Gi in hedgehog signaling placed in its most frequent context of Gli activation is, we believe, too narrowly framed. That Smo couples to Gi implies a potential for hedgehogs to regulate any number of pathways other than those that might bear on the activity of Gli. In this context, Smo may exhibit actions comparable to those of any other Gi-coupled receptor, whose importance need not relate to transcription much less Gli. We have referred to signaling achieved by Smo through Gi other than Gli as noncanonical (Brennan et al., 2012). In accordance with this notion, we found that migration of murine embryo fibroblasts in response to sonic hedgehog (Shh) through Smo requires Gi but does not involve Gli (Polizio et al., 2011). Migration requires, instead, sequential activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) and the monomeric G proteins Rac and Rho. PI 3-kinase is a well-documented target for Gi, as is Rac for PI 3-kinase and, in some cells, Rho for Rac. Use of of Gi and PI 3-kinase by Shh is also noted for endothelial cells in tubulogenesis (Kanda et al., 2003; Chinchilla et al., 2010). Gi apart from Gli is additionally reported to be directly responsible for hedgehog-dependent calcium spike activity in embryonic spinal cells (Belgacem and Borodinsky, 2011).

Any assertion that Smo is similar to other Gi-coupled receptors in its capacity to control the range of effectors described for Gi remains, however, tenuous. One could argue that the connection between Smo and Gi is a more residual than robust feature, with Smo having evolved to a form more apt to serve as a scaffold than to activate a G protein. In this case, the activation of Gi by Smo would be perceived by only especially sensitive effectors and, perhaps, only under special circumstances. The primary cilium, moreover, remains a structure in which support of G protein coupling and consequent action is uncertain. The paucity of reports regarding the use of Gi in hedgehog signaling adds to the uncertainty of the value of the G protein to the morphogen’s actions.

To understand better the notion of signaling through Gi as a meaningful facet of hedgehog action, we evaluated the efficacy of Smo specifically with regard to activation of the G protein, by comparing Smo with the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A (5-HT1A) receptor. The 5-HT1A receptor is a quintessential Gi-coupled receptor that, through Gi, links serotonin to a wide variety of effectors. We found, in the context of the assays that we used, that Smo is equivalent to the 5-HT1A receptor in activating Gi. We also extended the list of effectors targeted by hedgehogs through Gi from PI 3-kinase to adenylyl cyclase. Our data support Smo as a receptor with the potential to engage not only Gli but also many other, more immediate effectors.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Cyclopamine and purmorphamine were obtained from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); 8-hydroxy-2-(dipropylamino)tetralin hydrobromide (8-OH-DPAT), fluorescein isothyocyanate (FITC)–conjugated goat antibody specific for rabbit IgG, and Ptx were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Guanosine 5′-(3-O-thio)triphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) was provided by PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). Rabbit antibody specific for the hemagglutinin (HA) YPYDVPDYA sequence was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit antisera specific for Gα-subunits were described previously (Riobo et al., 2006). Recombinant Shh (N-terminal domain) was synthesized and purified as described elsewhere (Polizio et al., 2011).

Plasmid Constructs.

All expression constructs used the pcDNA3.1 vector. Those for human 5-HT1A wild-type and 3×HA-tagged (N-terminus) 5-HT1A receptor were obtained from the Missouri cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). The construct for mouse Smo wild-type receptor was provided by Dr. Philip Beachy (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA). cDNA for 3×HA-tagged Smo was constructed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–directed mutagenesis. The tag was inserted after the signal peptide: GGPGRGA33(Smo)/YPYDVPDYA(x3)/ A34(Smo)LSGNVT. Constructs for Smo-Gα and 5HT1A receptor-Gα fusion proteins were achieved by PCR-directed mutagenesis. The primary sequences at splice sites were TGHSDDEPKR566(Smo)/G2(Gai2)CTVSAEDKA (Smo/Gαi2), TGHSDDEPKR566(Smo)/G2(Gao)CTLSAEER (Smo/Gαo), TGHSDDEPKR566(Smo)/ G2(Gaz)CRQSSEEK (Smo/GαZ), FQNAFKKIIK416(5HT1A)/ G2(Gai2)CTVSAEDK (5-HT1A/Gαi2), FQNAFKKIIK416(5HT1A)/ G2(Gao)CTLSAEERA (5HT1A/Gαo), and FQNAFKKIIK416(5HT1A)/ G2(Gaz)CRQSSEEKE (5HT1A/GαZ). All DNA sequences after PCR-directed mutagenesis were verified by direct sequencing. The expression vector for mouse Gli2 and the 8×Gli luciferase reporter gene were obtained from Dr. Hiroshi Sasaki (RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan).

Cell Culture and Transfection.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 (CRL-1573) cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide. Cells were transfected at 70–80% confluency with use of Lipofectamine (Gibco). Expression constructs were adjusted to provide equal expression levels (5 μg HA-tagged 5-HT1A receptor, 40 μg Smo, and 40 μg receptor-Gα fusion constructs as noted in Results). The cells were maintained after transfection under normal culture conditions up to 48 hours before experiments. C3H10T1/2 cells (CCL-266) were also obtained from American Type Culture Collection. They were maintained in Basal Medium Eagle with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37° with 5% carbon dioxide. They were transfected using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol.

Membrane Preparation.

HEK-293 cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with cell lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 100 μM PMSF; 0.5 ml/100 mm dish) with rocking at 4°C for 20 minutes. The cells were collected into an eppendorf tube and passed 15 times through a 26G needle. Lysates were centrifuged at 2500g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to new eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 14,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Pellets (membranes) were resuspended in 100 μl cell lysis buffer by passing through a 26G needle and stored at −80°C.

[35S]GTPγS Binding.

The assay for receptor-promoted binding of [35S]GTPγS to Gα subunits was performed as described previously (Windh and Manning, 2002). Membranes (20 μg protein) were incubated with vehicle, agonist, or antagonist for 10 minutes at 30°C, then with 1 nM [35S]GTPγS (plus 10 μM GDP for Gi and Go, and 0.1 mM GDP for Gz) for another 10 minutes before solubilization of the membranes and immunoprecipitation of endogenous or fused Gα subunits for analysis by scintillation spectrometry. Binding was a near linear function of time and membrane amount.

Flow Cytometry.

HEK-293 cells transfected with HA-tagged Smo or HA-tagged 5-HT1A receptor expression constructs or with pcDNA 3.1 alone were trypsinized, washed, and incubated with PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or PBS/1% BSA containing HA-directed rabbit IgG at a 1:100 dilution. The cells were then washed and incubated with PBS/1% BSA containing FITC-conjugated goat antirabbit antibody (1:50) for 20 minutes, washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, NJ) and excitation/emission wavelengths of 488/530 nm.

cAMP Assay.

HEK-293 cells were plated at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well in standard 96-well microplates and cultured overnight. Cells were stimulated the following day for 5 minutes with 10 µM isoproterenol or vehicle in triplicate. Some wells were treated with 5 μM purmorphamine or 1 μM 8-OH-DPAT for 5 minutes or with 2 μg/ml recombinant Shh for 16 hours at 37°C before stimulation with isoproterenol. Intracellular cAMP was extracted and assayed by enzyme immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biotrak; GE Health Care Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Absorbance values were transformed to cAMP concentration with use of a standard curve generated by plotting the percentage bound for each standard and sample as a function of the log cAMP concentration.

Gli Reporter Gene Assay.

C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates and transfected with 0.1 µg 8×Gli firefly reporter, 0.01 µg TK Renilla reporter, and, where noted, 0.13 μg Gli2 expression vector. At 48 hours, when the cells had reached confluence, the serum was lowered to 0.5% serum, at which point, Ptx (100 ng/ml) or vehicle was added. The cells were treated 20 hours thereafter with or without purmorphamine. Luciferase activities were evaluated 4 hours later with use of the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Western Blotting.

A total of 1 μg (HA-tagged receptors) or 10 μg (receptor-Gα fusion proteins) of membrane protein for each lane were dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. The membranes were blotted with anti-HA (#3724S Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or with anti-Gα antisera at a 1:1000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies with ECL immunoblot kits (GE Health Care Biosciences) were used for visualization.

Statistics.

Comparison of two groups was made using a paired Student’s t test with use of GraphPad Prism, version 5.0. N and P values are noted in figure legends.

Results

Smo couples directly to members of the Gi family of heterotrimeric G proteins (Riobo et al., 2006). Whether the activation of Gi by Smo is comparable in degree to that of other Gi-coupled receptors, however, is unknown, because expression in the previous study was neither controlled nor specifically evaluated. Toward this end, we constructed an epitope-tagged form of Smo and a set of Smo-Gα fusion proteins for comparison with similar forms of the 5-HT1A receptor.

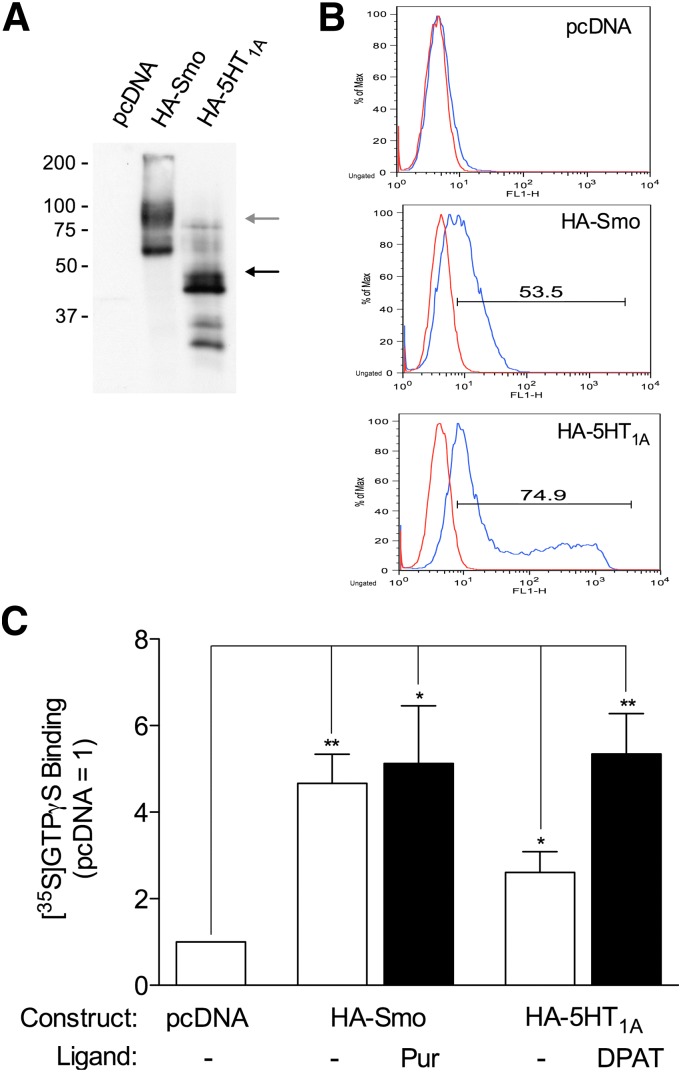

HA-tagged forms of Smo and the 5-HT1A receptor were introduced into HEK-293 cells by transfection. Several bands for the receptors were evident in Western blots (Fig. 1A). In the case of Smo, the larger, more diffuse band(s) around 85 kDa corresponded to the size anticipated for the full-length tagged receptor (87.4 kDa). For the 5-HT1A receptor, the doublet around 46 kDa was near the size anticipated (49.4 kDa). Heterogeneity in banding may reflect glycosylation and/or proteolysis. Both receptors targeted to the cell surface, as noted by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). The expression of Smo at the cell surface was nearly monodisperse, whereas that of the 5-HT1A receptor was divided into a subset of cells in which expression was equivalent to that of Smo and another subset in which expression was higher. Both receptors promoted binding of [35S]GTPγS to subtypes of Gαi present in the HEK-293 cells with or without agonist, as evaluated using an antiserum recognizing Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 (Fig. 1C). Activities without agonist are consistent with constitutive activity, a hallmark of Smo when unrepressed by Ptch1 (Riobo et al., 2006; Riobo and Manning, 2007; Jiang and Hui, 2008; Wilson and Chuang, 2010) and a characteristic of the 5-HT1A receptor (Barr and Manning, 1997; Martel et al., 2007). The activity of Smo toward Gi was not elevated further by the agonist purmorphamine. The activity of the 5-HT1A receptor toward Gi was doubled with 8-OH-DPAT. In the context of the assay, the activity of Smo with or without purmorphamine was equal to or greater than that of the 5-HT1A receptor under either circumstance.

Fig. 1.

Activation of Gi endogenous to HEK-293 cells by Smo and 5-HT1A receptor. HEK-293 cells near confluence (10-cm plates) were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 alone or the vector encoding HA-tagged Smo or HA-tagged 5-HT1A receptor. Cells or subsequently prepared membranes were evaluated 48 hours after transfection. (A) Expression of the receptors was evaluated for membranes (1 μg membrane protein) by a Western blot using HA-directed antibody. Positions of molecular weight standards are noted. Arrows refer to mobilities predicted for full-length receptors (gray arrow, HA-tagged Smo; black arrow, HA-tagged 5-HT1A receptor) based on molecular weight standards. The depiction is representative of four experiments total. (B) Expression of receptors was evaluated for intact cells by flow cytometry using either no primary antibody (red) or HA-directed antibody (blue) with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Horizontal bars represent cutoffs for expression and equate to transfection efficiency. The depiction is representative of three experiments total. (C) Activity of the receptors toward one or more forms of Gi endogenous to HEK-293 cells was evaluated in membranes by [35S]GTPγS binding. Binding of the radioligand was examined with or without 10 μM purmorphamine (HA-Smo) or 1 μM 8-OH-DPAT (HA-5-HT1A) and normalized to binding obtained with pcDNA alone. The data represent means ± S.E. for six independent experiments. Differences from pcDNA alone are noted (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01).

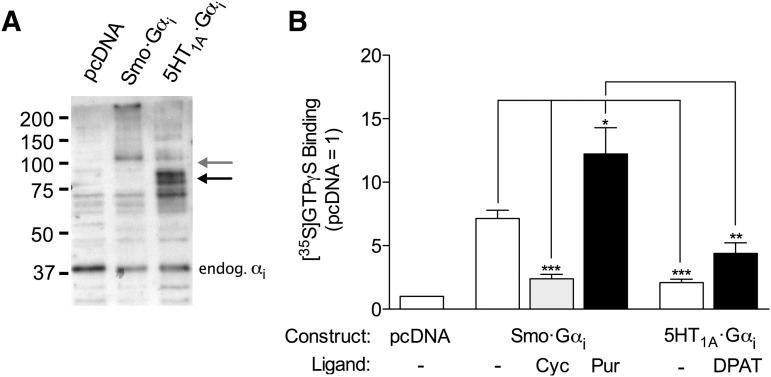

We evaluated coupling additionally with receptor-Gα fusion proteins. Fusion proteins have proven to be useful in studies of efficacy (Seifert et al., 1999; Milligan, 2000; Zhang et al., 2006) and, because of a common Gα subunit, permit quantitation of relative expression with Gα-directed antibodies. Western blotting confirmed expression of Smo-Gαi2 and 5-HT1A-Gαi2 (Fig. 2A). Smo-Gαi2 appeared primarily as two bands, one at ∼115 kDa, near the predicted molecular weight of 99.7 kDa, and the other at the top of the separating gel, likely representing aggregated protein. 5-HT1A-Gαi2 appeared mostly as doublet around 85.8 kDa, close to the predicted molecular weight of 86 kDa. A substantive constitutive activity was noted for Smo-Gαi2, as it was noted above for Smo alone with endogenous Gi (Fig. 2B). The activity was not the result of the appended Gα subunit in some way operating apart from the receptor, because it was largely suppressed by the inverse agonist cyclopamine. Purmorphamine was found to increase the activity of Smo-Gαi2. Both constitutive and agonist-promoted activities exhibited by Smo-Gαi2, as measured by the assay, were greater than those exhibited by 5-HT1A-Gαi2.

Fig. 2.

Activation of Gαi within Smo-Gαi and 5HT1A-Gαi fusion proteins. HEK-293 cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 alone or the vector encoding Smo-Gαi2 or 5-HT1A-Gαi2 fusion protein. Membranes were evaluated 48 hours later. (A) Western blot using a Gαi2-directed antibody (1 μg membrane protein per lane). Arrows refer to mobilities predicted for full-length Smo-Gαi2 (gray arrow) and full-length 5-HT1A-Gαi2 (black arrow); Gαi endogenous to the cells is also noted. The depiction is representative of three experiments total. (B) [35S]GTPγS binding for the fusion proteins. Binding was evaluated with or without 10 μM purmorphamine (Smo-Gαi2), 10 μM cyclopamine (Smo-Gαi2), or 1 μM 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A-Gαi2) and normalized to binding obtained with pcDNA alone. The data represent means ± S.E. for 5–7 independent experiments. Differences from Smo-Gαi2 without ligands and between Smo-Gαi2 and 5HT1A-Gαi2 with agonists are noted (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001).

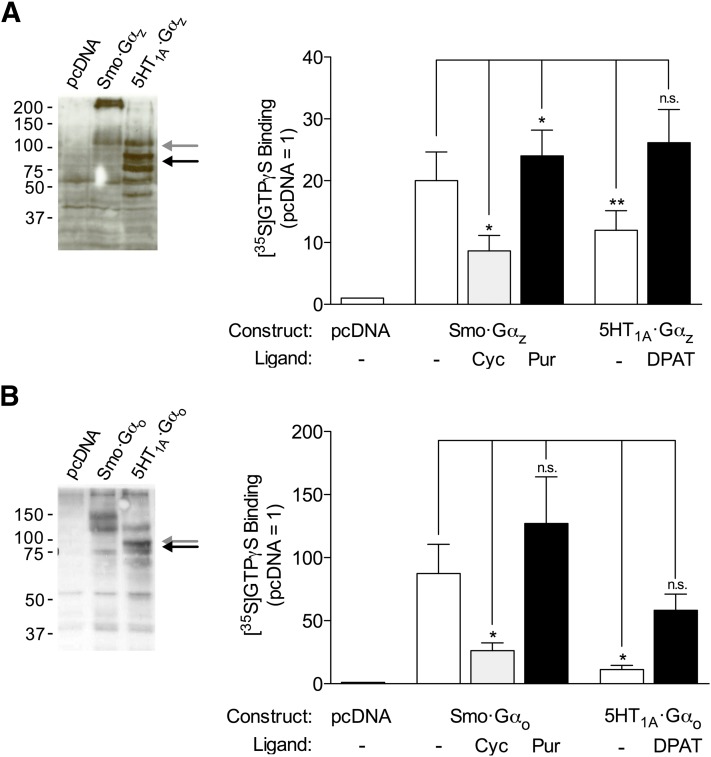

We evaluated interactions of the receptors with other members of the Gi family, again using receptor-Gα fusion proteins. Although Smo-Gαz was more prone to aggregation after electrophoresis than was Smo-Gαi2 (Fig. 3A), the [35S]GTPγS binding data for Smo-Gαz compared with 5-HT1A-Gαz were nearly identical to those for Smo-Gαi2 compared with 5-HT1A-Gαi2 above. Smo-Gαo resolved as a doublet with an apparent molecular weight higher than anticipated (Fig. 3B). The reason for the shift from the anticipated molecular weight is unknown. The data for this construct compared with 5-HT1A-Gαo were nonetheless similar to those of Smo-Gαi2 compared with 5-HT1A-Gαi2, with the exception that binding of [35S]GTPγS relative to control, pcDNA, was higher. Notwithstanding the noted electrophoretic anomalies and consequent difficulties in evaluating precise expression levels, the activities of Smo-Gα in each case appeared in the assay to be at least comparable to those of 5-HT1A-Gα.

Fig. 3.

Activation of Gαo and Gαz in receptor-Gα fusion proteins. HEK293 cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 alone or the vector encoding (A) Smo-Gαz or 5-HT1A-Gαz, or (B) Smo-Gαo or 5-HT1A-Gαo. Arrows refer to mobilities predicted for full-length Smo-Gα (gray arrows) and full-length 5-HT1A-Gα (black arrows). [35S]GTPγS binding assays were performed as described in Fig. 2 but using Gαo- and Gαz-directed antibodies and represent means ± S.E. for 4–5 and 6–8 independent experiments, respectively. Differences from Smo-Gα without ligand are noted (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; n.s., not significant).

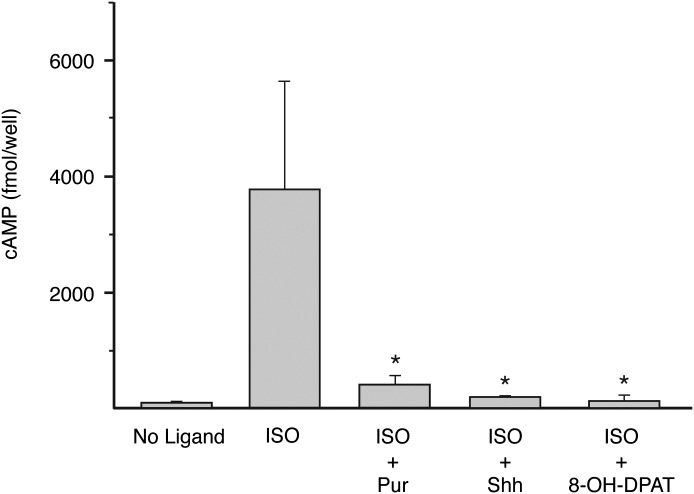

HEK-293 cells express endogenous Ptch1 and Smo (Jiang et al., 2009; Atwood et al., 2011), neither of which had an appreciable impact on [35S]GTPγS binding in the context of receptor overexpression above. We found, in experiments to evaluate effectors downstream of Gi, however, that endogenous Smo is fully capable of mediating inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. As shown in Fig. 4, addition of purmorphamine or Shh to HEK-293 cells achieved significant inhibition of isoproterenol-stimulated increases in cAMP. The inhibition was no greater with overexpressed Smo (as evaluated for purmorphamine; data not shown). HEK-293 cells also express endogenous 5-HT1D receptor (Atwood et al., 2011), which similar to the 5-HT1A receptor recognizes 8-OH-DPAT as an agonist and couples to Gi (Andrade et al., 2012). Similar to endogenous Smo, it had little impact on the [35S]GTPγS binding above. 8-OH-DPAT, similar to purmorphamine and Shh, inhibited isoproterenol-stimulated increases in cAMP. Smo endogenous to HEK-293 cells reduces cAMP to the same extent as does the presumptive 5-HT1D receptor.

Fig. 4.

Decreases in isoproterenol-elevated cAMP with purmorphamine, Shh, and 8-OH-DPAT. HEK-293 cells were treated with vehicle, 10 μM isoproterenol alone, or 10 μM isoproterenol after pretreatment with 5 μM purmorphamine, 2 μg/ml Shh, or 1 μM 8-OH-DPAT. cAMP was measured by enzyme immunoassay. The three ligands were each found to decrease isoproterenol-elevated cAMP (*P ≤ 0.05). The data represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

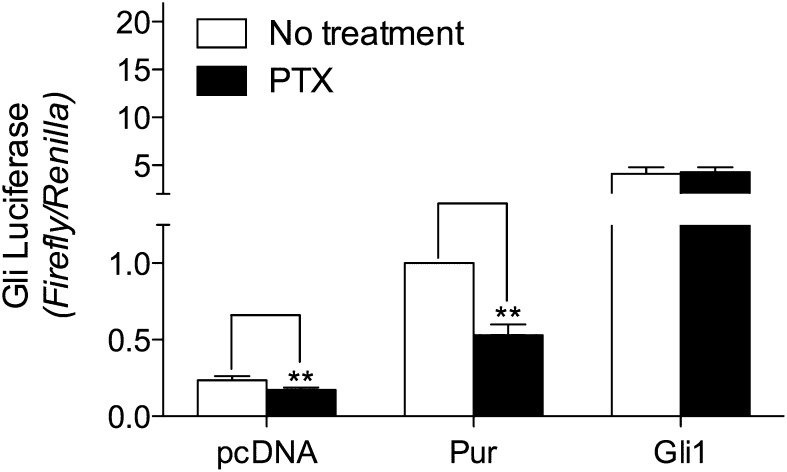

We also evaluated the requirement of Gli for Gi, because unequivocal data for the requirement in mammalian cells are limited to a single type of cell, the NIH 3T3 fibroblast (Riobo et al., 2006). We had found little if any effect of purmorphamine on Gli activity in HEK-293 cells (Douglas et al., 2011). We turned therefore to C3H10T1/2 cells, a mesenchymal cell line used often as a model for Smo action on Gli. As noted (Wu et al., 2004), purmorphamine activates the Gli reporter gene in C3H10T1/2 cells, as does Gli1 (Fig. 5). The activation of the reporter gene by purmorphamine in these cells was sensitive to Ptx, with the toxin inhibiting activation by 50%. The activation caused by Gli1 was, as anticipated, not sensitive to the toxin.

Fig. 5.

Ptx-sensitivity of Gli activation in C3H10T1/2 cells. C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected with vectors for 8×Gli firefly and TK Renilla luciferase reporters and, where noted, Gli1. At 48 hours, after attainment of confluence by the cells, serum was lowered to 0.5% and (black bars) Ptx was added to a concentration of 100 ng/ml. Purmorphamine (10 μM) was added 20 hours thereafter. Luciferase activities were assayed after an additional 4 hour. The data represent means ± S.E. of ratios of firefly to Renilla activities normalized to those obtained for purmorphamine without Ptx for six independent experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Our most important finding is that Smo is comparable to the 5-HT1A receptor in its capacity to activate Gi as measured in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay. Equivalence was demonstrated in two ways: first, with forms of Gi endogenous to HEK-293 cells made to express epitope-tagged receptors and, second, with individual forms of Gαi fused to the C terminus of each receptor. We also found that Smo endogenous to HEK-293 cells inhibits adenylyl cyclase, a finding that corroborates the efficacy of Smo through Gi and extends the list of effectors controlled by Smo through Gi beyond PI 3-kinase. Finally, the requirement for Gi in the activation of Gli was documented for C3H10T1/2 cells, demonstrating that the requirement is not unique to a single type of mammalian cell.

Both Smo and the 5-HT1A receptor exhibited agonist-independent (constitutive) receptor activity. The activity was particularly prominent for Smo, with little if any additional activity achieved in response to purmorphamine. Although HEK-293 cells express Ptch1, it is likely that levels of Smo introduced into the cells exceed those that endogenous Ptch1 can suppress or that Ptch1-mediated repression of Smo is disrupted with preparation of membranes. Thus, we believe that the activity noted for the introduced Smo represents a propensity of the receptor to enter into a nearly fully active conformation. It is possible that the Smo-Gα constructs (Smo-Gαi2 and Smo-Gαz) exhibit some degree of response to purmorphamine because of an inhibitory constraint of the appended subunit on constitutive activity. The 5-HT1A receptor, while exhibiting constitutive activity, can, in all cases, be activated further by agonist. The activity of constitutively active Smo toward Gi in the context of the [35S]GTPγS assay is nonetheless equal to or greater than that of either constitutively active or agonist-activated 5-HT1A receptor.

It was important in these studies to be assured of comparable receptor expression. HA tagging permitted analysis of expression at the cell surface that showed differences in expression to be modest or in favor of the 5-HT1A receptor. However, although the HA-tagged 5-HT1A receptor has been extensively documented in terms of functionality, the mammalian HA-tagged Smo has not. For this reason, we adopted the additional strategy of using as tags Gα subunits appended to truncated receptor tails. As noted, receptor-Gα fusion proteins have been effectively used to evaluate efficacy as it relates to all classes of Gα subunit. The results regarding activities for the Smo-Gα-tagged compares with 5-HT1A-Gα–tagged receptors were the same as those for the HA-tagged receptors (i.e., Smo was at least the equivalent of the 5-HT1A receptor, as measured in the assay).

Previous work with membranes of Sf9 cells made to express Smo and individual G proteins suggested that Gz was more readily activated than was Go (Riobo et al., 2006). We found, in the present study using receptor-Gα fusion proteins, little difference between Smo and the 5-HT1A receptor in activation of individual subtypes of Gαi (i.e., Gαi2, Gαz, and Gαo). This finding does not imply that one or another Gα subunit is not selectively activated by Smo, only that Smo does not differ from the 5-HT1A receptor in this regard. This would imply that any selectivity is intrinsic to the G protein and not to receptors. Transactivation of endogenous Gαi can possibly occur for any of the fusion proteins (Burt et al., 1998; Molinari et al., 2003); however, the subtype selectivity of the antibodies helps to ensure that the subunits assayed in the case of Gαz and Gαo are those appended to the receptor.

Whether the potential of a receptor to communicate with a G protein as deduced through [35S]GTPγS binding is fully realized in an endogenous setting depends on several factors. One of the most important is levels of expression of the receptor. Work with adenylyl cyclase here and activation of Rac and Rho through PI 3-kinase in murine embryo fibroblasts (Polizio et al., 2011) demonstrates that, in at least some cells, for at least two effectors, sufficient levels of expression are achieved. The subcellular distribution of a receptor is another factor that can impact on a receptor’s capacity to interact with a G protein. In the case of Smo, whether the primary cilium to which it is recruited after activation contains Gi or any one or more of Gi’s targets is unclear. Gαi2 and Gαi3, when overexpressed in cerebellar granular neuronal precursors, target the cilium (Barzi et al., 2011); however, targeting of endogenous subunits in these cells or elsewhere may be different. Our studies with HEK-293 cells were performed at confluence, a condition that supports formation of primary cilia. Our previous studies with murine embryo fibroblasts regarding Rac and Rho were performed at subconfluence. We suspect, therefore, that Smo can communicate with Gi both in and beyond primary cilia.

Our study, to our knowledge, is the first to show that the activation of mammalian Smo decreases intracellular cAMP in an endogenous setting. The impact of vertebrate Smo on cAMP was indicated previously only after overexpression (DeCamp et al., 2000). The data for cAMP in HEK-293 cells are in agreement with findings for Drosophila (Ogden et al., 2008). A decrease in the activity of the most common target for cAMP, the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, is widely considered to be a requirement in the activation of Gli by hedgehog (Epstein et al., 1996; Barzi et al., 2010; Milenkovic and Scott, 2010). Our finding and that for Drosophila (Ogden et al., 2008) are consistent with the decrease being caused by activated Smo directly through the effects of Gi on adenylyl cyclase before or after entry of Smo into the primary cilium. The decrease in cAMP was noted at 16 hours for Shh, suggesting that the interaction of Smo with Gi is less susceptible to desensitization than are those of most other receptors, for which the effects are generally transient. One possibility is that the interaction of Smo with arrestin, after initiated, lasts only until Smo is translocated to the primary cilium, allowing interactions of Smo with Gi to occur not only before but after the process of translocation. It is also possible that the affinity of arrestin for Smo is less strong than that for other receptors, allowing Gi to more effectively compete for access, or that a population of Gi targeting adenylyl cyclase is, for some reason, unavailable to arrestin. Smo-effected decreases in cAMP may not always be easily discerned. Barzi et al. (Barzi et al., 2010) suggest that a decrease in cAMP may be localized to the primary cilium, such that overall cellular levels of cAMP may not seem to change. If localization of Smo to the primary cilium holds true in HEK-293 cells, the proportion of adenylyl cyclase that is inhibited or the degree to which it is inhibited must be large. A pressing question, given the consensus regarding the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, is why Gi is not always required in the activation of Gli. A possible requirement for Gi may be related to cell-intrinsic levels of cAMP. If levels are sufficiently high to block activation of Gli, Gi would be required. If not, Gi would not be required. This possibility remains to be tested.

The equivalence of Smo to the 5-HT1A receptor in activation of Gi and decrease through endogenous Smo of cAMP provides evidence of Smo as a receptor that can engage not only Gli but other more immediate effectors. Effectors thus far identified are PI 3-kinase and adenylyl cyclase; however, the list for Gi extends to other enzymes and ion channels. The regulation of these, in turn, may explain the increasing number of hedgehog-induced events that occur too quickly for any action of Gli or that can otherwise be mimicked by agonists working through Gi-coupled receptors other than Smo. Such events include axonal guidance (Yam et al., 2009), proliferation of neuronal stem cells (Lai et al., 2003; Banasr et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2004; Tran et al., 2007), β-selection of thymocytes (Shah et al., 2004), and potentiation of CD4+ T cell activation (Stewart et al., 2002; Chan et al., 2006). Our documentation of noncanonical signaling (Polizio et al., 2011) and, here, efficacy of Smo acting on Gi provides a rationale for evaluating these events and the prediction of others.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kimberly Aranda for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT1A

5-hydroxytryptamine1A

- 8-OH-DPAT

8-hydroxy-2-(dipropylamino)tetralin hydrobromide

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- FITC

fluoresceine isothiocyanate

- Gli

Gli transcription factors

- GTPγS

guanosine 5′-(3-O-thio)triphosphate

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI 3-kinase

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Ptch1

Patched1

- Ptx

a Bordetella pertussis toxin

- Shh

sonic hedgehog

- Smo

smoothened

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Shen, Cheng, Douglas, Riobo, Manning.

Conducted experiments: Shen, Cheng, Douglas.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Shen.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Shen, Cheng, Douglas, Riobo, Manning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant GM080396].

References

- Andrade R, Barnes NM, Baxter G, Bockaert J, Branchek T, Cohen ML, Dumuis A, Eglen RM, Göthert M, Hamblin M et al.(2012) 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors: 5-HT1A IUPHAR Database: http://www.iuphar-db.org/DATABASE

- Atwood BK, Lopez J, Wager-Miller J, Mackie K, Straiker A. (2011) Expression of G protein-coupled receptors and related proteins in HEK293, AtT20, BV2, and N18 cell lines as revealed by microarray analysis. BMC Genomics 12:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Hery M, Printemps R, Daszuta A. (2004) Serotonin-induced increases in adult cell proliferation and neurogenesis are mediated through different and common 5-HT receptor subtypes in the dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:450–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AJ, Manning DR. (1997) Agonist-independent activation of Gz by the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor co-expressed in Spodoptera frugiperda cells. Distinguishing inverse agonists from neutral antagonists. J Biol Chem 272:32979–32987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzi M, Berenguer J, Menendez A, Alvarez-Rodriguez R, Pons S. (2010) Sonic-hedgehog-mediated proliferation requires the localization of PKA to the cilium base. J Cell Sci 123:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzi M, Kostrz D, Menendez A, Pons S. (2011) Sonic Hedgehog-induced proliferation requires specific Gα inhibitory proteins. J Biol Chem 286:8067–8074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgacem YH, Borodinsky LN. (2011) Sonic hedgehog signaling is decoded by calcium spike activity in the developing spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:4482–4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D, Chen X, Cheng L, Mahoney M, Riobo NA. (2012) Noncanonical Hedgehog signaling. Vitam Horm 88:55–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt AR, Sautel M, Wilson MA, Rees S, Wise A, Milligan G. (1998) Agonist occupation of an α2A-adrenoreceptor-Gi1α fusion protein results in activation of both receptor-linked and endogenous Gi proteins. Comparisons of their contributions to GTPase activity and signal transduction and analysis of receptor-G protein activation stoichiometry. J Biol Chem 273:10367–10375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan VSF, Chau SY, Tian L, Chen Y, Kwong SKY, Quackenbush J, Dallman M, Lamb J, Tam PKH. (2006) Sonic hedgehog promotes CD4+ T lymphocyte proliferation and modulates the expression of a subset of CD28-targeted genes. Int Immunol 18:1627–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla P, Xiao L, Kazanietz MG, Riobo NA. (2010) Hedgehog proteins activate pro-angiogenic responses in endothelial cells through non-canonical signaling pathways. Cell Cycle 9:570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCamp DL, Thompson TM, de Sauvage FJ, Lerner MR. (2000) Smoothened activates Galphai-mediated signaling in frog melanophores. J Biol Chem 275:26322–26327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE, Heim JA, Shen F, Almada LL, Riobo NA, Fernández-Zapico ME, Manning DR. (2011) The α subunit of the G protein G13 regulates activity of one or more Gli transcription factors independently of smoothened. J Biol Chem 286:30714–30722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DJ, Marti E, Scott MP, McMahon AP. (1996) Antagonizing cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in the dorsal CNS activates a conserved Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Development 122:2885–2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. (1998) The effect of pertussis toxin on zebrafish development: a possible role for inhibitory G-proteins in hedgehog signaling. Dev Biol 194:166–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Hui CC. (2008) Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell 15:801–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Yang P, Ma L. (2009) Kinase activity-independent regulation of cyclin pathway by GRK2 is essential for zebrafish early development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:10183–10188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Xie L, Kim SH, Parmentier-Batteur S, Sun Y, Mao XO, Childs J, Greenberg DA. (2004) Defective adult neurogenesis in CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol 66:204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda S, Mochizuki Y, Suematsu T, Miyata Y, Nomata K, Kanetake H. (2003) Sonic hedgehog induces capillary morphogenesis by endothelial cells through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem 278:8244–8249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K, Kaspar BK, Gage FH, Schaffer DV. (2003) Sonic hedgehog regulates adult neural progenitor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci 6:21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low W-C, Wang C, Pan Y, Huang X-Y, Chen JK, Wang B. (2008) The decoupling of Smoothened from Galphai proteins has little effect on Gli3 protein processing and Hedgehog-regulated chick neural tube patterning. Dev Biol 321:188–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel J-C, Ormière A-M, Leduc N, Assié M-B, Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A. (2007) Native rat hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors show constitutive activity. Mol Pharmacol 71:638–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic L, Scott MP. (2010) Not lost in space: trafficking in the hedgehog signaling pathway. Sci Signal 3:pe14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. (2000) Insights into ligand pharmacology using receptor-G-protein fusion proteins. Trends Pharmacol Sci 21:24–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari P, Ambrosio C, Riitano D, Sbraccia M, Grò MC, Costa T. (2003) Promiscuous coupling at receptor-Galpha fusion proteins. The receptor of one covalent complex interacts with the α-subunit of another. J Biol Chem 278:15778–15788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden SK, Fei DL, Schilling NS, Ahmed YF, Hwa J, Robbins DJ. (2008) G protein Galphai functions immediately downstream of Smoothened in Hedgehog signalling. Nature 456:967–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polizio AH, Chinchilla P, Chen X, Kim S, Manning DR, Riobo NA. (2011) Heterotrimeric Gi proteins link Hedgehog signaling to activation of Rho small GTPases to promote fibroblast migration. J Biol Chem 286:19589–19596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riobo NA, Manning DR. (2007) Pathways of signal transduction employed by vertebrate Hedgehogs. Biochem J 403:369–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riobo NA, Saucy B, Dilizio C, Manning DR. (2006) Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by Smoothened. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12607–12612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DK, Hager-Theodorides AL, Outram SV, Ross SE, Varas A, Crompton T. (2004) Reduced thymocyte development in sonic hedgehog knockout embryos. J Immunol 172:2296–2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R, Wenzel-Seifert K, Kobilka BK. (1999) GPCR-Galpha fusion proteins: molecular analysis of receptor-G-protein coupling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 20:383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GA, Lowrey JA, Wakelin SJ, Fitch PM, Lindey S, Dallman MJ, Lamb JR, Howie SEM. (2002) Sonic hedgehog signaling modulates activation of and cytokine production by human peripheral CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 169:5451–5457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Banisadr G, Ren D, Chenn A, Miller RJ. (2007) Chemokine receptor expression by neural progenitor cells in neurogenic regions of mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 500:1007–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CW, Chuang P-T. (2010) Mechanism and evolution of cytosolic Hedgehog signal transduction. Development 137:2079–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windh RT, Manning DR. (2002) Analysis of G protein activation in Sf9 and mammalian cells by agonist-promoted [35S]GTP γ S binding. Methods Enzymol 344:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Walker J, Zhang J, Ding S, Schultz PG. (2004) Purmorphamine induces osteogenesis by activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Chem Biol 11:1229–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam PT, Langlois SD, Morin S, Charron F. (2009) Sonic hedgehog guides axons through a noncanonical, Src-family-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. Neuron 62:349–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, DiLizio C, Kim D, Smyth EM, Manning DR. (2006) The G12 family of G proteins as a reporter of thromboxane A2 receptor activity. Mol Pharmacol 69:1433–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]