Abstract

5′–Βenzylglycinyl-amiloride (UCD38B) and glycinyl-amiloride (UCD74A) are cell-permeant and cell-impermeant derivatives of amiloride, respectively, and used here to identify the cellular mechanisms of action underlying their antiglioma effects. UCD38B comparably kills proliferating and nonproliferating gliomas cells when cell cycle progression is arrested either by cyclin D1 siRNA or by acidification. Cell impermeant UCD74A inhibits plasmalemmal urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and the type 1 sodium-proton exchanger with potencies analogous to UCD38B, but is cytostatic. In contrast, UCD38B targets intracellular uPA causing mistrafficking of uPA into perinuclear mitochondria, reducing the mitochondrial membrane potential, and followed by the release of apoptotic inducible factor (AIF). AIF nuclear translocation is followed by a caspase-independent necroptotic cell death. Reduction in AIF expression by siRNA reduces the antiglioma cytotoxic effects of UCD38B, while not activating the caspase pathway. Ultrastructural changes shortly following treatment with UCD38B demonstrate dilation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial swelling followed by nuclear condensation within hours consistent with a necroptotic cell death differing from apoptosis and from autophagy. These drug mechanism of action studies demonstrate that UCD38B induces a cell cycle-independent, caspase-independent necroptotic glioma cell death that is mediated by AIF and independent of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and H2AX activation.

Introduction

High-grade gliomas (HGGs) are a highly aggressive type of primary central nervous system cancers, accounting for 78% of adult central nervous system malignancies (Dunn and Black, 2003; Buckner et al., 2007). Despite the use of current standard therapy, the 5-year survival for glioblastoma multiforme patients that receive optimal treatment is only 9%. Malignant gliomas recur in greater than 90% of cases despite radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or with antiangiogenic agents such as bevacizumab. The median progression free survival following these standard treatments are 39 and 30 weeks for World Health Organization grade 3 and 4 malignant astrocytomas, respectively (Lamborn et al., 2008).

The high recurrences rates of HGGs is, in part, a consequence of glioma initiating cells with “stem cell like” properties, which reside within perinecrotic and hypovascularized infiltrating tumor margins in proliferative and non-proliferative states (Franovic et al., 2009). Persistent hypoxia in hypovascularized tumor regions of high-grade gliomas and other cancer cell types alters the transcriptional programming of glioma initiating cells, facilitating their survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, and increasing their resistance to apoptotic programmed cell death (type 1) by radiation therapy, conventional chemotherapy, and antiangiogenic therapies (Talks et.al., 2000; Aprelikova et al., 2006; Gordan et al., 2007; Koh et al., 2011). Recently, therapeutic targeting of cancer initiating cells that survive or thrive under hypoxic conditions has been recognized as essential for the successful treatment of HGGs and other aggressive and recurrent forms of cancer.

Components of the urokinase plasminogen activator system (uPAS), notably urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA), its receptor uPAR, and the endogenous serpin plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) demonstrate increased expression in hypoxic-ischemic tumor domains of high-grade gliomas (Brat et al., 2004). Increased uPAS expression are predictive biomarkers for solid proliferative cancer cell types having a propensity to proliferate, recur, and metastasize (Schmitt et al., 2011). uPA and uPAR are secreted by cancer and stromal cells, and uPA binding to plasmalemmal uPAR on the cancer cell augments uPA activity by more than 30-fold, activating plasmin with the resultant activation of a protease cascade causing degradation of the extracellular matrix. To date, therapeutic inhibitors of plasmalemmal uPA have been demonstrated to have a cytostatic effect on cancer cells with small molecules currently in clinical phase 3 testing in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents (Ulisse et al., 2009). Much less is known about the function of intracellular uPAS. The proenzyme, high molecular weight uPA exists in equilibrium with uPA within the cytoplasm. Intracellular uPA is bound at its active site to the serpin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). PAI-1 is a chaperone protein that translocates uPA and its receptor to the cell surface. Here, cell-permeant and -impermeant 5′−glycinyl analogs of 3,5-diamino-N-(aminoiminomethyl)-6- chloropyrazine carboxamides are employed to determine the cellular mechanisms mediating the selective antiglioma cytotoxicity of the cell-permeant derivative against proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cells (Massey et al., 2012).

Traditionally, cell death has been classified into regulated (apoptosis) and unregulated (necrosis) forms. Accumulating evidence now shows that necrosis is controlled, regulated, and executed through defined pathways and is a series of programmed events termed necroptosis. Necrotic cell death is identified by disruption of the plasma membrane causing the leakage of cell contents to the surroundings and distinguished from apoptosis and from autophagy by the early swelling of intracellular organelles, including the ER and mitochondria, followed by the loss of plasma membrane integrity (Amaravadi and Thompson, 2007). As with apoptosis, necrotic cell death occurs in both physiologic and pathologic conditions and can be mediated by different programmed cell death pathways utilizing key proteins, which include TRAIL, RIP1, TRAF2, JNK1, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1, calpains, Bax, and AIF (Amaravadi et al., 2007; Golstein and Kroemer, 2007). One such PCD protein, apoptotis-inducing factor (AIF), is a mitochondrial oxidoreductase released into the cytoplasm that is translocated into the nucleus to initiate nuclear condensation followed by caspase-independent necrosis. PARP activation can signal AIF nuclear translocation in glioma cells during apoptosis and under circumstances where activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway has been inhibited (Kondo et al., 2010).The DNA damage triggered by AIF causes nuclear condensation and is most often coupled to the subsequent activation of H2AX, a member of the histone protein family whose phosphorylation is activated by DNA double-strand breaks initiated by AIF. Here we demonstrate that a cell-permeant uPA inhibitor (5′−benzylglycinyl-amiloride [UCD38B]) is cytotoxic to proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cell lines, whereas the cell impermeant analog (5′−glycinyl-amiloride [UCD74A]) (Massey et al., 2012) is cytostatic but not cytotoxic to glioma cell lines. Amiloride is cytotoxic to glioma cells at higher concentration than UCD38B and has been shown elsewhere (Harley et al., 2010) to use a different cytotoxic mechanism of action than that shown for UCD38B. This cell-permeant 5′−benzylglycinyl analog of 3,5-diamino-N-(aminoiminomethyl)-6- chloropyrazine carboxamide initiates necroptotic glioma cell death in proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cells utilizing an AIF-mediated pathway that does not require activation of PARP or of H2AX and utilizes this cancer-selective cell death mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Drugs

UCD38B and UCD74A were synthesized as described previously (Palandoken et al., 2005; Massey et al., 2012). Amiloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Drugs stocks of 250 mM were constituted in dimethylsulfoxide and were used at a final concentration of 250 μM.

PARP inhibitor, 3-aminobenzamide (Sigma-Aldrich), and pan caspase inhibitor VI, z-VAD-fmk [benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (Calbiochem; Billerica, MA)] were added to the cell culture medium at 20 μM for 1 hour. Cells were incubated for 1 hour before treatment with amiloride and its derivatives.

Cell Culture

Human U87 glioblastoma cells (U87MGs) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Rockford, IL), 1% l-Glutamine (200 mM; Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco).

siRNA Transfections

On-Target plus siRNA for AIF, uPA, and cyclin D1 were purchased from Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Lafayette, CO). Transfections were performed using Dharmacon siRNA transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions and protocol. Cells were harvested 3, 4, and 5 days post-transfections.

Flow Cytometry.

Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol following cyclin D1 siRNA transfections. DNA was stained with propidium iodide at 50 μg/ml. Fluorescent intensities were measured using a Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) flow cytometer at 488 nm for excitation and at 650 nm for emission. The cell cycle profile was analyzed using Modifit’s Sync Wizard (Verity Software Inc., Topsham, ME).

LDH Cell Death Assay.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was used to measure the release of cytosolic LDH from dying glioma cells. Ten thousand cells per well were plated in 96-well microtiter plate and treated with the drugs for 24–48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. LDH assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Absorbance was read at 492 nm using a SpectraMax M3 with SoftmaxPro software (LifeSciSoft, Kingston, NY).

Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay.

Examining cells for trypan blue exclusion was also used to distinguish viable from nonviable cells. Following drug treatment, cells were trypsinized, resuspended in PBS, and 4% trypan blue was added in 1:1 ratio. An aliquot was transferred to a manual hemocytometer for manual cell counting after 3 minutes.

Enzyme Assays.

Inhibition of enzymatic assays for uPA was described previously (Massey et al., 2012). Briefly, purified human uPA and colorimetric urokinase peptide substrate was obtained from Calbiochem, and 10 U of enzyme was used per reaction. Both enzyme and substrate were diluted in Tris buffer saline. Reaction product was monitored colorimetrically in 96-well microtiter plates using a SpectraMax M3 and the kinetics were analyzed with SoftmaxPro software.

Cytotoxicity in Proliferating and Nonproliferating Glioma Cells

Cell cycle arrest was induced in U87MGs by transfecting gliomas cells with siRNA of cyclin D1 or using acidified culture media as described elsewhere (Schnier et al., 2008). Cells were incubated for 48 hours post-transfection and then harvested for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis or for immunoblotting. Cell cycle arrest was also achieved by maintaining U87MGs under acidotic conditions at pHext 7.4, pHext 6.6, or pHext 6.0, and cell cycle arrest was shown by FACS analysis (Schnier et al., 2008). Cells were exposed to the small molecules or dimethylsulfoxide vehicle only, and cell death was determined using the LDH cytotoxic assay.

Immunocytochemistry

The U87MG cells were cultured in chamber slides. Cells were treated with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride for 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours at 250 μm at 37°C. Mitochondria were visualized by staining with MitoTracker (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed with PBS and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at −20°C for 15 minutes, followed by washing with PBS and permeabilizing with 80% methanol in PBS at −20°C for 5 minutes. Blocking was done with 3% NFDM/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with primary antibody in 0.1% BSA/PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Mouse anti-AIF monoclonal antibody (mAb), mouse anti–PAI-1 mAb (1:100 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and mouse anti–uPA-mAb and mouse anti-uPAR(1:100 dilution; American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT) were used as primary antibodies. Secondary antibody was used at 1:500 dilution in 0.1% BSA/PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG) conjugated with Alexa Flour 488 (1:500 dilution; Molecular Probes). After the PBS wash, the slides were mounted with mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes). Immunocytochemistry was visualized using 40× objective with a spinning disk confocal microscope (Olympus IX81; Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA).

Electron Microscopy

U87MG cells were plated in Laboratory-Tek Permanox chamber 8-well slides from Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA. Cells were treated with drugs UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride at 250 μM for 1 hour. Cells were fixed in Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.0% paraformaldehyde) for 1 hour. The cells were then washed in 100 mM phosphate buffer and secondarily fixed for 1 hour in 1% osmium tetroxide and 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in double-distilled H2O. Cells were washed with cold double-distilled H2O three times to remove the fixative. Dehydration followed through ascending concentrations of ethanol (30, 50, 70, 95, and 100%) with a minimum of 10 minutes in each and three changes of 100%. A 100% concentration of epon-araldite resin that does not contain nadic methyl anhydride was added to each well and allowed to infiltrate overnight at room temperature. The next day the resin was removed by warming the slides in the polymerization oven for about 10 minutes following by drainage of nonpolymerized resin. New resin was added and slides were polymerized at 70°C. Following polymerization, regions of interest were chosen and the area was cut to the need size using a fine bladed (jewelers) saw. Cells were visualized in the Philips 120 BioTwin electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) at 80 kV equipped with a Gatan MegaScan, model 794/20 digital camera.

Immunoblot Analysis

Protein extracts were made in RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and 50 μg of proteins was loaded on SDS-PAGE. For cytosolic and nuclear fractions, 5×106 cells were seeded. Cells were harvested and washed in 1× PBS buffer. Cells were resuspended into 20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 hypotonic buffer. NP40 (10%) was added and samples were vortexed at maximal speed for 10 seconds. Centrifugation was done at 3000g to isolate the pellet (nuclear) and supernatant (cytosolic) fractions. The nuclear enriched fraction was resuspended in 50 μl of RIPA lysis buffer. Protease inhibitors, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfoxyl fluoride, 4 μg/ml Pepstain, 4 μg/ml aprotinin were added to RIPA buffer. This was incubated for 30 minutes on ice vortexing every 10 minutes. The samples were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 14,000g at 4°C, and supernatant (nuclear fractions) were collected. For mitochondrial enriched fractions, cells were harvested and washed with 1× PBS. Cells were resuspended in mitochondrial isolation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, and 0.1 mM EGTA) and homogenized using Dounce homogenizer. Samples were centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes to pellet the nuclei. Supernatant was collected in new tube and centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 minutes to collect the pellet (mitochondria) and supernatant (cytosolic) fractions. The pellet was solubilized in lysis buffer and centrifuged to pellet the debris. Protein samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane by immunoblotting. Blocking was done for 1 hour in blocking buffer/1× PBS with 1:1 dilution. Primary antibody (1:1000) incubation was done overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were anti-cyclin D1, anti-AIF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-uPA (American Diagnostic), mouse monoclonal anti-caspase-3 and anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology), H2AX, γH2AX polyclonal, polyclonal glyceraldehyde 3-phosphase dehydrogenase and actin. Secondary antibody incubation was done at room temperature for 1 hour. Mouse secondary antibody from Licor Biosciences and goat anti-mouse HRP-linked secondary antibody were used at 1:10,000 dilution. Bands were visualized using Odyssey Infrared Imager (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance was determined for cell number and cytotoxicity using one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's nonparametric, multiple pairwise comparisons using SigmaStat software version 2.00 (SPSS Science Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Amiloride and UCD38B, but Not UCD74A, Are Cell Permeant in U87MG Cells.

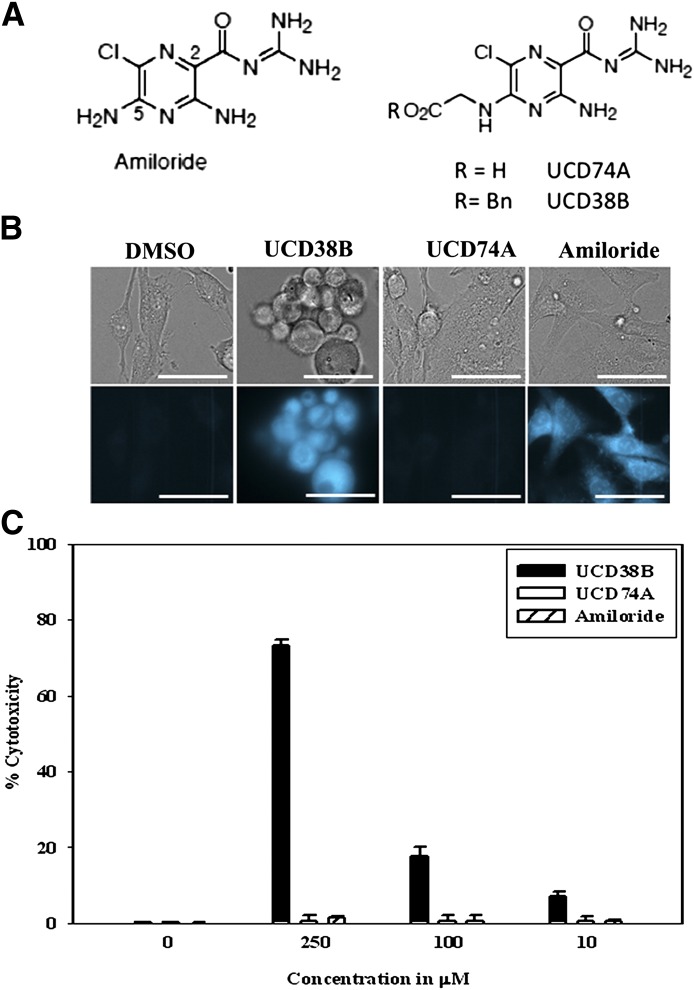

Amiloride has multiple sites of action, including its inhibition of sodium-mediated transporters, acid-sensing inward channel, sodium channels and urokinase plasminogen (uPA) located on the cell surface (Harley et al., 2010). Inhibition by Amiloride of cell surface type 1 sodium-proton exchanger (NHE1) and acid-sensing inward channel are primarily cytostatic, whereas dual inhibition of NHE1 and forward sodium-calcium exchange by NCX1.1 account for amiloride’s weak anticancer cytotoxicity (Harley et al., 2010). The activities in Table 1 demonstrate that UCD38B and UCD74A have comparable inhibitory activities of uPA and NHE1 yet fundamentally differ in their cell permeability. Amiloride and its derivatives UCD38B and UCD74A are intrinsically fluorescent, having excitation and emission at 380 and 510 nm, respectively. U87MG cells were incubated with either UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride for 1 hour followed by buffer replacement and visualized intracellularly. Following incubation and buffer change, UCD38B and amiloride demonstrated significant intracellular fluorescence, as compared with UCD74A (Fig. 1B) (Palandoken et al., 2005).

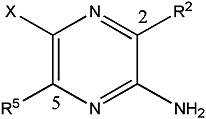

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory activities of amiloride, UCD38B, and UCD74A

The inhibitory activities of amiloride, UCD38B, and UCD74A against the type 1 sodium proton exchanger (NHE1) were evaluated in human U87MG gliomas cells (Hegde et al., 2004) and demonstrated comparable inhibitory activities. The inhibitory activities of amiloride and these C5-substituted amiloride derivatives demonstrated minimal activity against the sodium calcium exchanger (NCX 1.1) that was stably expressed in CHO cells, as we described previously (Harley et al., 2010). UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride comparably inhibit purified urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA).

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R2 | R5 | X | uPA IC50 | NHE1 IC50 | NCX 1.1 IC50 | U87 Glioma Cytotoxicity |

| μM | μM | μM | μM | ||||

| Amiloride | Acyl guanidine (H2N)2C=NC(O)- | NH2 | Cl | 7 | 60 | 690 | 250 |

| UCD38B Am-C(5)-Gly-OBn | Acyl guanidine (H2N)2C=NC(O)- | NHCH2CO2Bn | Cl | 3 | 13 | >250 | 100 |

| UCD74A Am-C(5)-Gly-OH | Acyl guanidine (H2N)2C=NC(O)- | NHCH2CO2H | Cl | 17 | 13 | >250 | No cytotoxicity |

Fig. 1.

(A) Chemical structures of amiloride and the 5-glycinyl derivatives, UCD74A and UCD38B. (B) U87MG cells were incubated for 1 hour with UCD38B, UCD74A, amiloride (250 μM), or DMSO (dimethylsulfoxide) control. The media were changed and cells were rinsed with PBS and visualized using a fluorescent microscope. UCD38B and amiloride but not UCD74A are cell permeant and visualized as intracellular fluorescence by fluorescence microscopy. Cells were imaged using 40× objective and the scale bar represents 50 μm. Upper panel shows the bright field, and lower panel shows the fluorescence images. (C) Cytotoxicities of UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride at 250, 100, and 10 μΜ on human U87MG glioma cells relative to control at 24 hours were determined by LDH assay. Data represent the mean ± S.D. determined from three independent experiments.

UCD38B and Amiloride are Cytotoxic to U87MG Cells.

The anticancer cytotoxic activities of UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride on U87MG glioma cells were investigated following 24 hours of treatment using the LDH assay. The LDH assay in this cell line was previously shown to correspond closely with manual cell counts of viable and nonviable gliomas cells using the trypan blue exclusion assay (Harley et al., 2010). All three small molecules inhibit glioma cell proliferation so that the release of LDH by dead and dying cells was selected as a measure of drug cytotoxicity rather than using live cell assays, such as the tetrazolium assays (Harley et al., 2010). U87MGs were treated with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride at 250 μM for 24 hours. At 250 μM, UCD38B was more cytotoxic to human U87MG glioma cells than amiloride or UCD74A; the latter being inactive (Fig. 1C). The LC50 for UCD38B is 100 μM compared with the parent compound amiloride with LC50 of 250 μM (Table 1). Given the comparable inhibitory activities of UCD38B and UCD74A against NHE1 and uPA, the cytotoxicity data and the cell permeability results suggested that an intracellular target(s) is important for mediating the anticancer cytotoxicity of UCD38B and Amiloride.

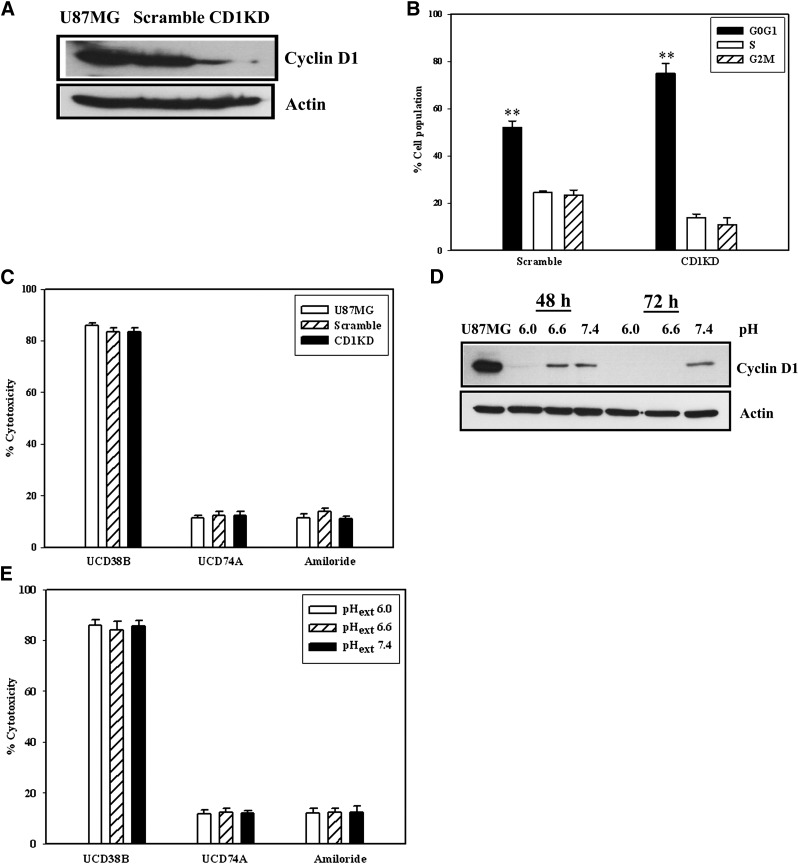

UCD38 is Cytotoxic to Proliferating and Nonproliferative U87MG Cells.

It was important to determine if this class of small molecules is cytotoxic to nonproliferating glioma cells that have been identified within high-grade gliomas. Tumor regions of hypovascularity have regions of micronecrosis and macronecrosis that contain glioma cells arrested throughout the cell cycle as a consequence of an acidic tumor microenvironment (Reichert et al., 2002; Schnier et al., 2008). Cell cycle arrest was induced in U87MG glioma cells utilizing two different mechanisms. Knock down of cyclin D1 protein levels using siRNA was demonstrated at 48 hours by immunoblotting by using anti-cyclin D1 antibody (Fig. 2A). Reduction of cyclin D1 protein expression using siRNA reduced U87MG cell proliferation with increased accumulation at the G0/G1 stage as demonstrated by FACS (Fig. 2B). However, UCD38B was comparably cytotoxic to stage-matched proliferating cells and U87MG cells transfected with cyclin D1 siRNA with no shift in the dose-response profiles as demonstrated by LDH cytotoxicity assay. By comparison, UCD74A and amiloride were not cytotoxic to nonproliferating U87 glioma cells at 24 hours following anticyclin D1 antisense (Fig. 2C). Under acidotic conditions, cell cycle progression was arrested throughout all stages, and cyclin D1 levels were maximally reduced at pH6.0ext, as previously reported (Schnier et al., 2008). Immunoblot shows that cyclin D1 levels were reduced under acidotic conditions (Fig. 2D). At 250 μM, UCD38B was comparably cytotoxic to U87 glioma cells through the pHext range from 6.0 to 7.4, whereas UCD74A and amiloride did not demonstrate cytotoxicity (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Drug cytotoxicity in proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cells. U87MG cells were untreated (U87MG) or transfected with scramble (scramble) or cyclin D1 siRNA (CD1KD) siRNA oligonucleotides for 48 hours. (A) Protein levels of cyclin D1 following 48 hours siRNA transfection were detected by Western blot using anticyclin D1 antibody and normalized to actin. (B) fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed at 48 hours comparing scramble or CD1KD siRNA transfected glioma cells. n = 3, **P < 0.01. (C) LDH cytotoxic assay comparing the relative cytotoxicities of the UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride in U87MG untreated control, scramble, and CD1KD siRNA transfected cells. (D) Immunoblot demonstrating levels of cyclin D1 in acidified media at 48 hours and 72 hours. (E) LDH assay of drugs UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride at pH 6.0, 6.6, and 7.4. Results and standard deviation represent three to five independent experiments.

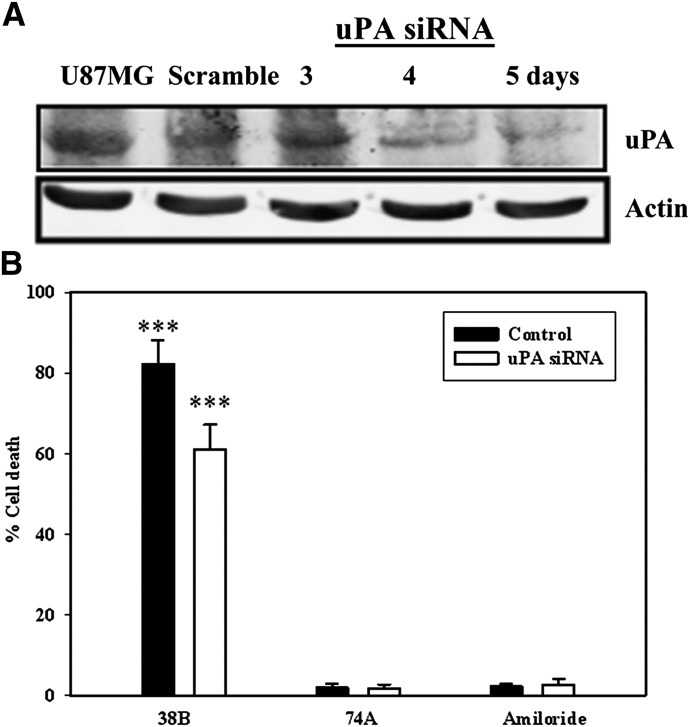

Reduction of uPA Partially Inhibits the Cytotoxicity of UCD38B in U87MG Cells.

UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride are micromolar inhibitors of uPA, ranging from IC50 7 to 17 μM (Table 1). Therefore, we investigated whether intracellular uPA or its proenzyme could represent a potential drug target conferring drug cytotoxicity. siRNA transfection was used to reduce protein levels of uPA to investigate whether this knockdown impaired the cytotoxic activities of UCD38B and amiloride.

Immunoblot blot analysis demonstrated decreased protein expression of total cellular uPA on days 4 and 5 following uPA siRNA transfections (Fig. 3A). The cytotoxic activities of UCD38B, UCD74A, and amiloride were determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay on the 4th day of uPA downregulation by siRNA. Their cytotoxic potencies were compared with control glioma cells transfected with scramble siRNA. Following partial uPA knockdown, UCD38B killed 23% fewer glioma cells compared with control cells (Fig. 3B). As negative controls, glioma cells treated with amiloride or UCD74A were not affected compared with control cells. The LDH cytotoxic assay was not used because manual cell counts determined that cellular LDH content was altered by siRNA transfection.

Fig. 3.

uPA siRNA and UCD38B antiglioma cytotoxicity. Glioma cells transfected with either uPA or scramble siRNA were incubated for 3, 4, and 5 days. (A) Reduced protein levels of uPA on days 4 and 5 were observed on blots normalized to actin as an internal control. (B) Cells were treated for 6 hours with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride on day 4 post-transfection of uPA or scramble siRNA (control). Cell death was determined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 with ***P < 0.001.

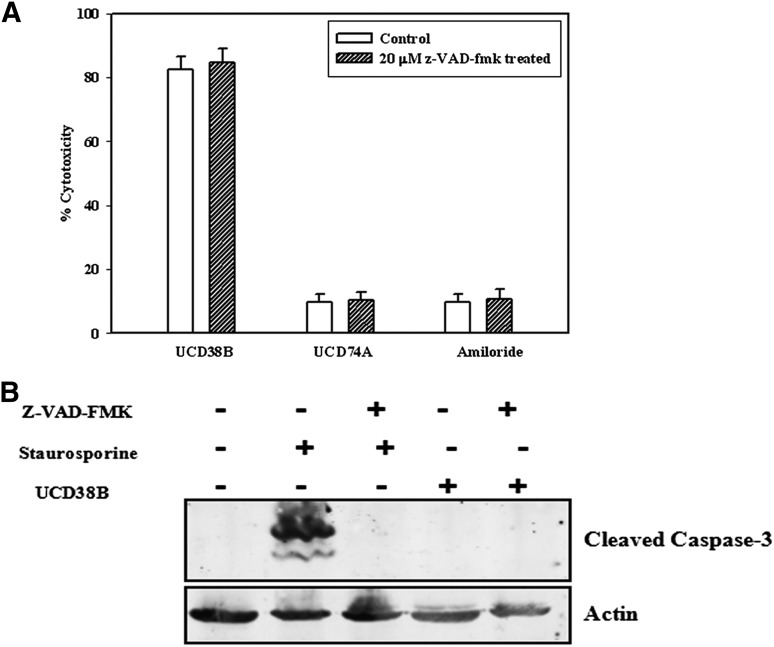

UCD38B Kills Glioma Cells Independent of Caspase Activation.

An irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor was used to determine whether the glioma cell death pathway initiated by UCD38B had caspase dependency. Cells were treated with 20 μM caspase inhibitor VI, z-VAD-fmk, for 1 hour prior to treatment with either UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride at 100 μM, 200 μM (unpublished data), and 250 μM. Glioma cell death produced by UCD38B was unaffected in presence of z-VAD-fmk, consistent with a possible caspase-independent cell death pathway (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, caspase-3 activation was not observed on immunoblot in U87MG cells treated only with UCD38B (Fig. 4B). As a positive control, caspase-3 activation was observed in glioma cells treated with staurosporine, which could be prevented by preincubation with the pan-caspase inhibitor.

Fig. 4.

38B caused cell death without the activation of caspases. (A) Caspase activities were inhibited by 1 hour pretreatment with 20 μM z-VAD-fmk followed by 24-hour treatments with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride. LDH cytotoxic assays were performed and no significant changes in drug cytotoxicities were observed in untreated and treated gliomas cells. (B) Caspase -3 cleavage by staurosporine (1 μM) was prevented by pretreatment with Z-VAD-fmk (20 μM), whereas no caspase-3 activation was detected on immunoblot following UCD38B treatment.

UCD38B Promotes Organelle Changes in Gliomas within an Hour.

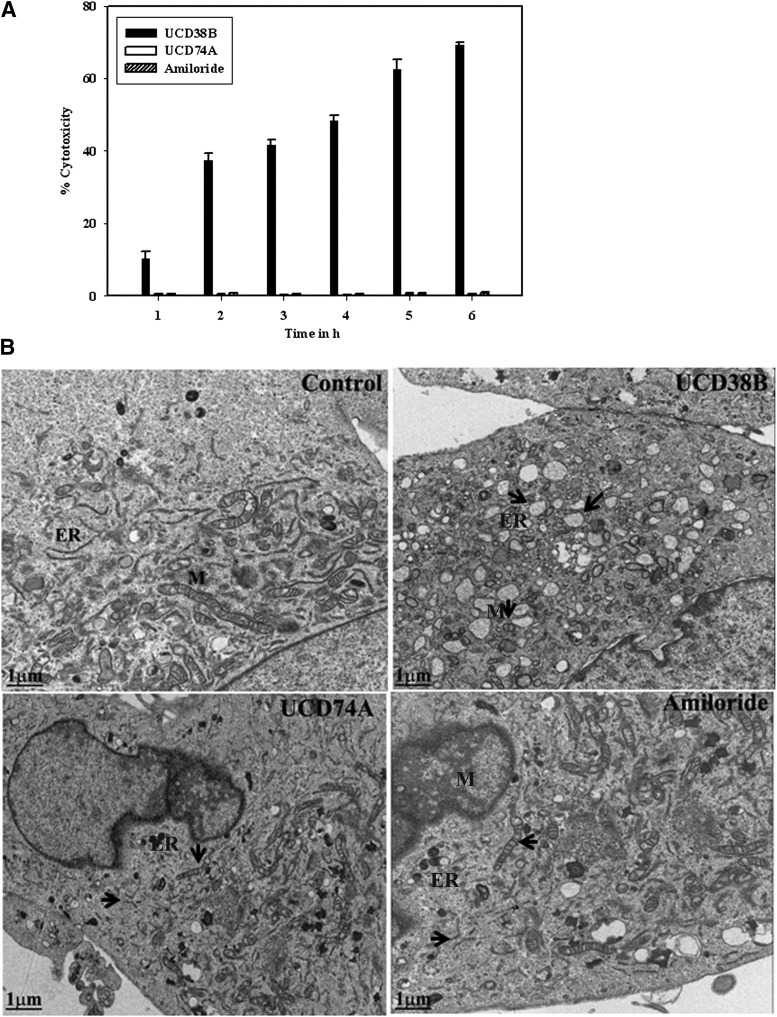

A 6-hour time course monitored glioma cell death by following LDH release in U87MG cells treated with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride at 250 μΜ. More than 50% of glioma cells were killed by UCD38B after 2 hours, but no cells were killed with UCD74A or amiloride (Fig. 5A). Early cytologic changes using electron microscopy were then examined over 2-hour time interval to obtain insights into the cell death morphology produced by UCD38B. Without drug treatment (control), the mitochondria in control U87MG glioma cells were healthy with well-defined cristae and the ER demonstrated normal elongation and cytoplasmic distribution with an intact nuclear membrane (Fig. 5B). By contrast, morphologic changes in the organelles were noted within 1 hour of exposure to UCD38B. Treated glioma cells demonstrated rounded and swollen mitochondria, dilation of ER, and increased cytoplasmic vacuolization. Condensation of the nucleus and nuclear membrane pore without nuclear fragmentation and enlarged lysosomes with increased lipid density were observed after 1 hour. Nuclear condensation without fragmentation is consistent with AIF-mediated cell death in the absence of apoptotic nuclear morphology. Simultaneous dilation of mitochondria and ER suggested that drug treatment could be associated with a mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and ER stress associated with cell death. Glioma cells treated with either UCD74A or amiloride at 250 μM did not demonstrate any morphologic changes in organelles or nuclei.

Fig. 5.

Early organelle morphologic changes in gliomas. (A) LDH assays were performed over 6 hours following treatment with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride (250 μM) to detect early cell death events. (B) Electron microscopy at 1 μm looked at cellular morphologic changes 1 hour after drug treatments. Arrows indicate the changes in the ER and mitochondria, M. ER was dilated and realignment of mitochondrial cristae was observed. Golgi reorganization, nuclear condensation and nuclear membrane pores without nuclear fragmentation, lysosomes with increased lipid density, and increased vacuolization were observed following 1-hour drug treatments with UCD38B compared with control, UCD74A, and amiloride.

UCD38B Alters Intracellular Trafficking of uPA to the Mitochondria.

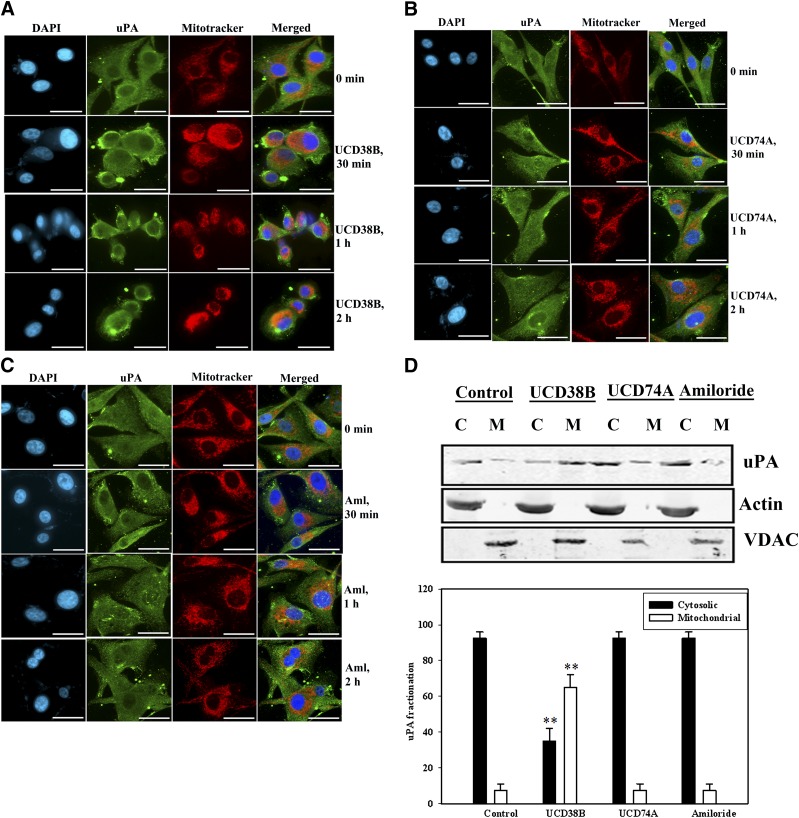

The effects of UCD38B treatment on uPA were then investigated using immunocytochemistry and protein levels by immunoblotting. Exposure of U87MG cells to UCD38B initiated relocation of uPA within the cells. Mouse monoclonal uPA antibody demonstrated diffuse cytoplasmic and plasmalemmal uPA immunostaining in untreated control cells. Following treatment with UCD38B for 2 hours, uPA immunostaining was identified in a subset of perinuclear mitochondria (Fig. 6A) that was not observed following treatment with UCD74A (Fig. 6B) or amiloride (Fig. 6C). Subcellular enrichment of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions, followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using anti-uPA antibody confirmed that UCD38B exposure for 2 hours caused the appearance of uPA in the mitochondrial fraction, normalized to voltage-dependent anion channel, while modestly reducing the cytosolic content of uPA, as normalized to actin (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Intracellular trafficking of uPA to the mitochondria. U87MG gliomas cells were treated with UCD38B (A), UCD74A (B), and amiloride (C) for 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours. Mitochondria were visualized with MitoTracker, and an anti-uPA antibody was used to visualize intracellular and cytoplasmic uPA. Alexa 488 was used as secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. uPA (green) is localized in the cytoplasm in control cells. Following 2 hours of UCD38B treatment, a portion of intracellular uPA translocated to a subset of mitochondria. Scale bar is 50 μm. (D) Cytosolic, C, and mitochondrial, M, enriched fractions were separated on SDS-PAGE, and uPA was visualized on immunoblots and normalized to actin and VDAC (voltage dependent anion channel) as cytosolic and mitochondrial marker proteins, respectively. Densitometry is presented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 with **P < 0.01.

AIF Release and Translocation from Mitochondria into the Nucleus by UCD38B.

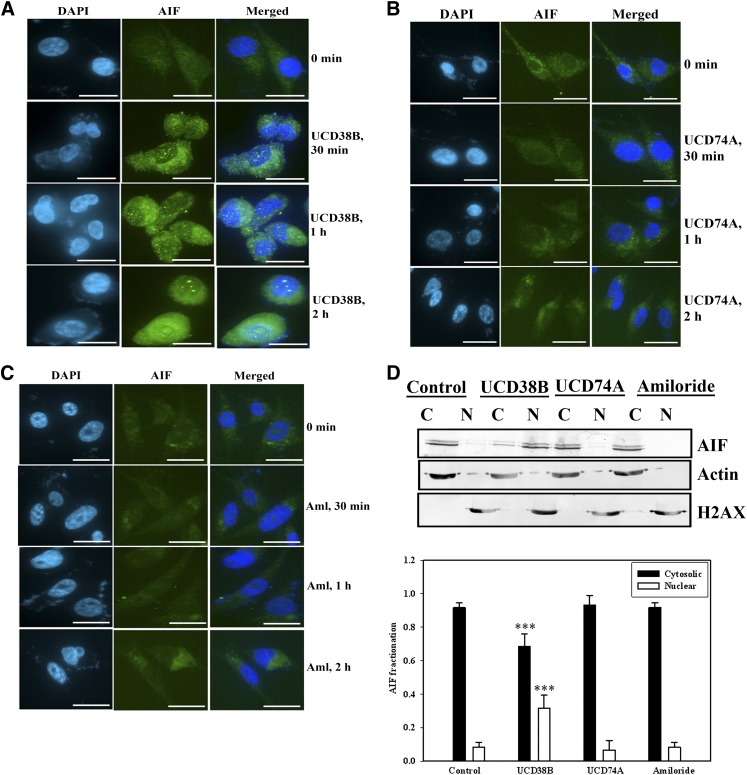

The nuclear condensation observed with EM following UCD38B treatment, coupled with dilation of ER and mitochondria, is characteristic of cell death mediated by AIF (Cande et al., 2002). AIF is an oxidoreductase in the intermitochondrial membrane space, and a reduction in the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (MMP) can release AIF into the cytosol with its subsequent nuclear translocation. Immunocytochemistry using confocal microscopy demonstrated that AIF (green) was translocated into the nucleus by 2 hours following exposure to UCD38B (Fig. 7A). Nuclear translocation of AIF was not observed when cells were treated with amiloride (Fig. 7B) or UCD74A (Fig. 7C). AIF translocation from mitochondria was confirmed biochemically by immunoblotting, demonstrating appearance of AIF in the nuclear enriched fraction following UCD38B treatment (Fig. 7D). AIF release and its appearance in the nuclear fraction were not observed following treatment with UCD74A or amiloride (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

AIF translocation from mitochondria into the nucleus. U87MG were treated with UCD38B (A), UCD74A (B), and amiloride (C) for 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours, and stained with AIF primary antibody and Alexa 488 secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. AIF (green) is visualized in the cytoplasm at 0 minutes. AIF migrated into the nucleus 2 hours after exposure to UCD38B, but not following treatment with UCD74A or amiloride. Scale bar is 50 μm. (D) Cytosolic, C, and nuclear, N, enriched cell fractions were separated on SDS-PAGE, and the translocation of AIF to the nuclear fractions were visualized on immunoblots following treatment with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and H2AX were used as cytosolic and nuclear marker proteins, respectively. Densitometry is presented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 with ***P < 0.001.

UCD38B Cytotoxicity Employs the Same Mechanism of Action in Proliferating and Nonproliferating Gliomas.

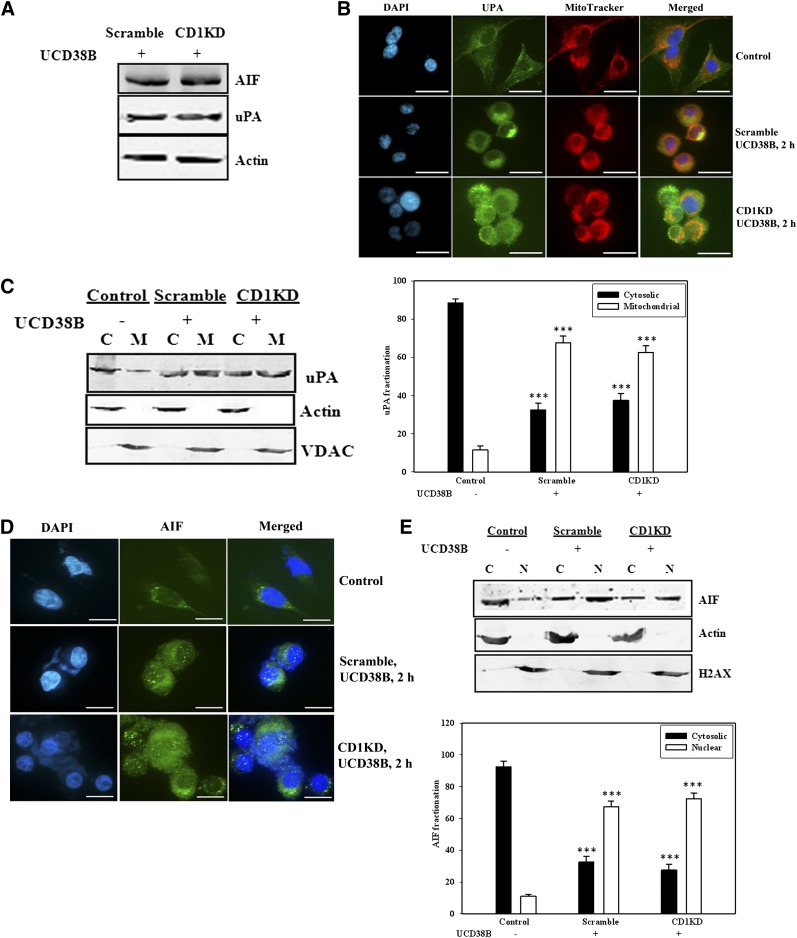

We investigated whether UCB38B induced cell death in nonproliferating cells using the same cell death machinery as in proliferating glioma cells. U87MG cells were transfected with cyclin D1 siRNA for 48 hours to inhibit cell cycle progression, which was confirmed by FACS analysis. Cells were then treated with UCD38B (250 μM) for 2 hours. The protein levels of uPA and AIF were comparable in gliomas cells transfected with scramble or CD1KD siRNA as detected on immunoblots normalized to actin (Fig. 8A). Translocation of uPA 2 hours after UCD38B treatment was examined by both immunofluorescence (Fig. 8B) and immunoblotting (Fig. 8C). uPA was translocated to perinuclear mitochondria in CD1KD glioma cells. Additionally, AIF trafficking from mitochondria to nucleus was observed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 8D) and by immunoblotting (Fig. 8E). These data indicate that UCD38B causes glioma cell death in proliferating and nonproliferating cells by employing the same cellular mechanism.

Fig. 8.

Cell death mechanism in nonproliferating cells. U87MG cells were transfected with scramble or cyclin D1 siRNA for 48 hour to inhibit cell cycle progression (Fig. 2). Glioma cells were then treated for 2 hours with UCD38B (250 μM). (A) Levels of uPA and AIF were quantitated and normalized to actin on immunoblots. (B) Immunofluorescence demonstrates translocation of uPA (green) from cytoplasm to perinuclear mitochondria (orange). (C) Immunoblot demonstrating the distribution of uPA in cytosolic, C, and membrane fractions, M, and densitometry of the immunoblot. (D) AIF immunofluorescence showing the translocation of AIF from mitochondria to nucleus. (E) Immunoblot showing the distribution of AIF in cytosolic, C, versus nuclear, N, enriched fractions and quantification of the blot. Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 with ***P < 0.001.

Reduction of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Following UCD38B Treatment.

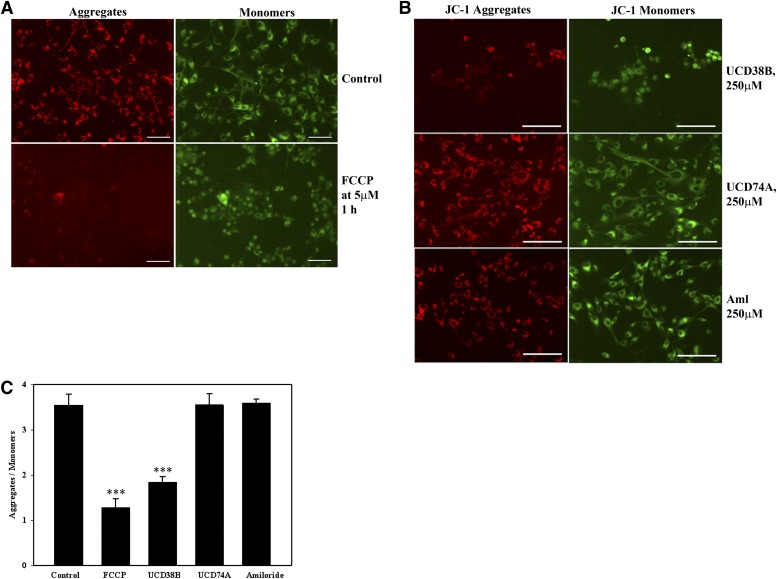

The mitochondrial release of AIF is frequently associated with cellular processes that decrease MMP. We investigated whether the localization of uPA to a subset of perinuclear mitochondria was temporally associated with a reduction in the MMP by using JC-1, a potentiometric fluorescence dye that is sequestered in the mitochondria (Cossarizza et al., 1993). In normally polarized mitochondria, JC-1 forms J-aggregates and monomers, depending on the state of the mitochondrial membrane potential. Normally polarized MMP in untreated U87 glioma cells that are preloaded with JC-1 predominantly demonstrates intramitochondrial J-aggregates (red) that fluoresce at 585 nm. With MMP depolarization, intramitochondrial aggregates disperse into monomers (green) that shift fluorescent emission to 530 nm. JC-1 in U87Mg cells was visualized microscopically and also separately measured spectroscopically. As a positive control, carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone, a protonophore, collapses MMP and causes the disappearance of JC-1 red aggregates (Fig. 9A). Following the addition of UCD38B, JC-1 aggregates slowly disappeared and only green monomers were observed by 1 hour. As negative controls, UCD74A and amiloride treatment did not demonstrate any observable change in JC-1 fluorescent emissions and were comparable with untreated controls (Fig. 9B). Similar results were obtained from fluorescent spectroscopy experiments indicating a reduction in ΜΜP (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential. U87MGs were treated with JC-1 (5 μM) for 30 minutes. (A) Control panels shows glioma cells treated 1 hour with JC-I or FCCP (carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) (5 μM) as positive control. JC-1 aggregates in red and monomers in green. (B) Cells were treated with JC-1 followed by UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride treatment of 1 hour. Scale bar is 25 μm. (C) MMP, as monitored by the ratio of fluorescent intensities of JC-1 aggregates to monomers, was measured 1 hour following drug treatments.

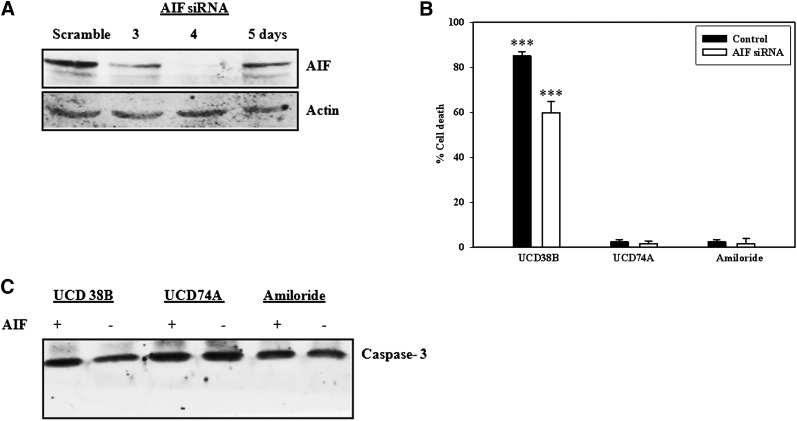

Inhibition of AIF Expression Attenuates the Antiglioma Cytotoxicity of UCD38B.

U87MG glioma cells were transiently transfected with AIF siRNA to identify whether AIF is responsible for mediating the antiglioma cytotoxicity of UCD38B. AIF protein expression was maximally decreased on day 4 and began to increase again on day 5 (Fig. 10A). U87MG cells transfected with AIF siRNA for 4 days earlier were treated with UCD38B and compared with UCD74A and amiloride to determine whether reduction in AIF cellular expression caused a delay or imparted resistance to drug treatment. Following treatment of 24 hours, glioma cell death as a percentage of total cell number was determined by manual cell counts using trypan blue staining nonviable cells. AIF siRNA interfered with LDH cytotoxicity assay, and hence trypan blue exclusion assay was performed. In glioma cells transfected with AIF siRNA and then treated with UCD38B, there was a delay in the initiation of necroptosis. Drug-induced cell death was reduced by 45% compared with glioma cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

AIF siRNA. AIF protein levels relative to actin were measured at 3, 4, and 5 days in U87MG cells transfected with AIF or scramble siRNA. (A) Reduced protein levels of AIF relative to actin on day 4 were observed on immunoblots in U87MG cells. (B) Trypan blue exclusion assay measured cell death in U87MG cells treated with UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride for 6 hours on day 4 of AIF or scramble (control) siRNA. Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 with ***P < 0.001. (C) Caspase-3 cleavage in treated glioma cells was not detected in immunoblots.

We examined whether AIF inhibition using siRNA switched drug-induced glioma cell death to a caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway. Caspase-3 was not activated following treatment with UCD38B 4 days after transfection with AIF siRNA (Fig. 10C). This latter result indicated that an alternate caspase cell death pathway was not turned on and that residual levels of AIF present in the transfected gliomas was likely sufficient to mediate the observed reduced cell death elicited by UCD38B.

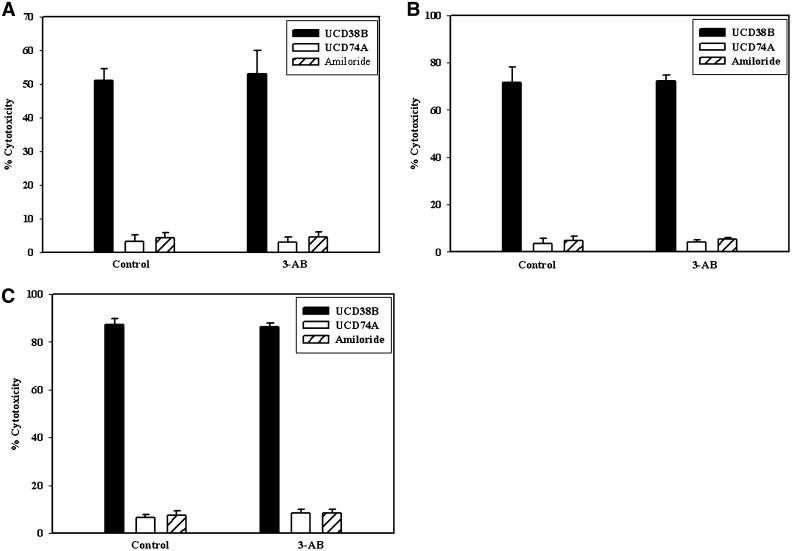

UCD38B-Induced Cell Death Does Not Require PARP-1 Cleavage.

Caspase cleavage of PARP-1 is a hallmark of apoptosis, and nearly all caspases have been shown to modify PARP-1 (Chaitanya et al., 2010). Furthermore, PARP-1 activation has been implicated in caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell death mediated by calpains, cathepsins, or apoptotic inducible factor (AIF) (Moubarak et al., 2007, Chaitanya et al., 2010). The PARP-1 inhibitor, 3-aminobenzamide (3-AB), was used to investigate whether PARP-1 activation was associated with the AIF release initiated by UCD38B. PARP-1 activation was inhibited by 3-AB (1 μM) pretreatment, followed by UCD38B and the LDH cytotoxic assay. No rightward shift of the UCD38B dose-response curve was observed, indicating that glioma cytoxicity from UCD38B was not abrogated by the PARP-1 inhibitor 3-AB (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

PARP inactivation and LDH cytotoxicity assay. U87MG glioma cells were treated with 3-AB (1 mM) for 1 hour prior to drug treatment to prevent PARP activation and followed by UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride treatments for 3 hours (A), 6 hours (B), and 24 hours (C). PARP inactivation by 3-AB did not inhibit or delay cell death.

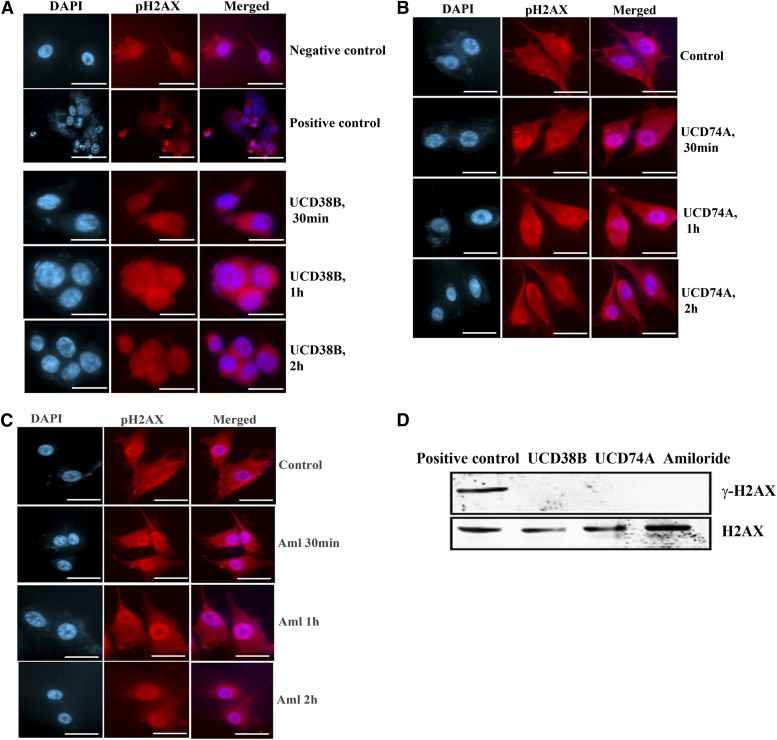

γH2AX Is Not Critical to AIF-Mediated Cell Death Induced by UCD38B.

Recently it was reported that caspase-independent necrosis mediated by AIF could demonstrate double-stranded nucleic acid nicking, which was associated with the phosphorylation on Ser139 of γH2AX, a member of histone H2A family (Baritaud et al., 2010. We investigated whether H2AX was phosphorylated in UCD38B-induced cell death by immunostaining and by immunoblot. We did not detect any γH2AX nuclear foci by immunofluorescence (Fig. 12, A–C), and Western blot analysis using an anti-γH2AX antibody confirmed the absence of phosphorylated γH2AX on immunoblot (Fig. 12D) normalized to H2AX that was visualized using an anti-H2AX antibody.

Fig. 12.

H2AX phosphorylation. U87MG glioma cells were treated with drugs UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride (250 μM). U87MG cells treated with staurosporine (1 μM) were used as positive control to demonstrate H2AX phosphorylation. Immunostaining (A, B, and C) of γH2AX in treated glioma cells was detected using anti-γH2AX polyclonal antibody. (D) Immunoblot of U87MG cells treated with staurosporine, UCD38B, UCD74A, or amiloride. Anti-γH2AX antibody was used to detect phosphorylated H2AX that was normalized to H2AX and detected using anti-H2AX antibody. Only H2AX was seen in treated cells except for staurosporine (positive control), which demonstrated γH2AX.

Discussion

Amiloride, an FDA-approved diuretic, acts on epithelial sodium channels and has been shown to inhibit the growth and metastasis of several tumor types in rat and mouse models (Sparks et al., 1983). At higher concentrations (≥500 μM), amiloride kills glioma cells by inhibiting the NHE1 and NCX1.1 transport protein (Harley et al., 2010). In this investigation, we identified that a cell permeant 5′-benzylglycinyl derivative of amiloride is cytotoxic to proliferating and nonproliferating high-grade glioma cells using a novel cell death mechanism. Glioma cell cycle arrest was achieved by cyclin D1 siRNA transfections or by simulating the acidic conditions within hypoxic-ischemic tumor regions. Cyclin D1 knockdown arrests glioma cells causing cell accumulation in G0/G1 phase. The acidic extracellular environment of pHext 6.0 arrests glioma cells throughout the cell cycle mimicking the extracellular perinecrotic tumor regions where pseudopalisading glioma cells do not proliferate while adjacent hypoxic glioma cells pass through S phase (Gorin et al., 2004; Schnier et al., 2008). Significantly, the cytotoxic efficacies of UCD38B are unaffected by either means of cell cycle arrest, and immunocytochemistry demonstrate that it triggers a common necroptotic programmed cell death pathway independent of glioma cell proliferation. Previously, we identified that amiloride in the high micromolar range kills human glioma cell lines and that its anticancer cytotoxicity is caspase independent (Hegde et al., 2004; Harley et al., 2010). Additionally, amiloride was found to selectively target proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cells residing in perinecrotic regions within intracerebral human U87 glioma xenografts implanted into NOD (non-obese diabetic) scid gamma immunodeficient mice (Gorin and Nantz, 2007). Other investigators reported that 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA) and hexamethylene amiloride reduce the growth, viability, motility, and invasiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and xenografts (Garcia-Canero et al., 1999).

Amiloride has multiple sites of action, including its inhibition of sodium-mediated transporters, acid-sensing inward channels, sodium channels, and urokinase plasminogen (uPA) located on the cell surface (Harley et al., 2010). Small molecule inhibitors of plasmalemmal urokinase plasminogen and its receptor uPAR have been developed since the mid-1990s, notably led by Wilex AG (Munich, Germany), which developed a nontoxic uPA inhibitor in phase 2 testing (Ulisse et al., 2009). These small molecules are cytostatic but not cytotoxic and use an entirely different drug mechanism of action than the amiloride analog, UCD38B.

Cell-permeant UCD38B and cell-impermeant UCD74A have comparable inhibitory activities against NHE1, uPA, and NCX1.1, yet the addition of a benzyl alcohol to the 5-glycinyl moiety of UCD74A confers anticancer cytotoxic activity compared with the free acid analog (Table 1). This suggests that the increased hydrophobicity of UCD38B permits access to an intracellular drug target. Cell-permeant amidine derivatives were synthesized to inhibit uPA, and cell-permeant analogs also demonstrated antiglioma cytotoxicity (Massey et al., 2012). In this investigation we identify that UCD38B appears to target intracellular uPA and possibly its proenzyme forms. Reducing the expression of uPA by siRNA inhibited glioma cell death induced by UCD38B. Cytologic studies demonstrated that a portion of intracellular uPA translocated from the glioma cell cytoplasm to a subset of perinuclear mitochondrial within 2 hours following UCD38B treatment. Subsequent structure-activity studies of more than 30 C(5)-substituted amiloride analogs has confirmed the importance of intracellular permeation and of targeting the active site of intracellular uPA. Additional synthetic amiloride derivatives have augmented the anticancer cytotoxicity of UCD38B by more than 200-fold (LC50 < 2 μM), while retaining the same cancer cell selectivity, drug targeting, and cell death mechanisms (unpublished data).

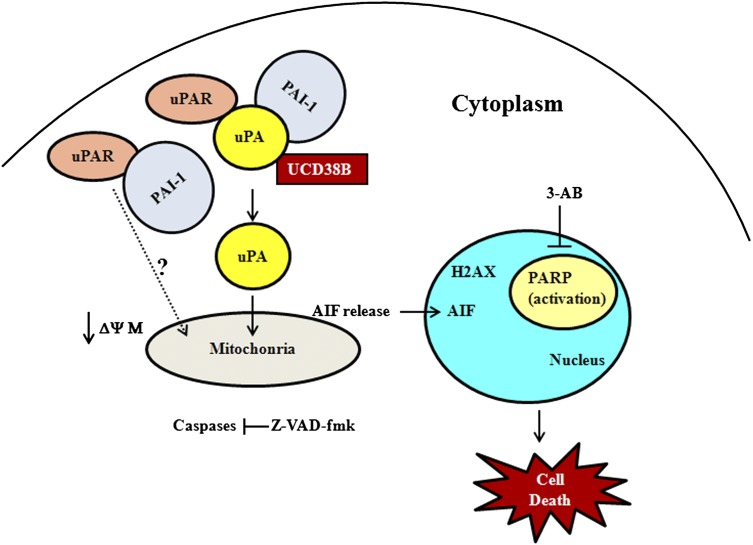

We report here that UCD38B is more effective than UCD74A and its parent drug amiloride as an anticancer cytotoxic agent. UCD38B induces cell death of U87MG glioma cells by an AIF-mediated pathway that is independent of caspase-3 and PARP-1 activation (Fig. 13). Electron microscopy studies demonstrate early swelling of the intracellular lumens of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria with subsequent vacuolization and nuclear condensation that are consistent with cell death mechanistic studies suggesting programmed necrosis. Other studies have shown the requirement of PARP activation for the release of AIF from mitochondria (Andrabi et al., 2006). In this investigation, inhibition of PARP-1 activation does not prevent drug-induced glioma cell death by UCD38B, indicating that AIF mediates caspase-independent necrosis without the activation of PARP-1. The translocation of intracellular uPA to perinuclear mitochondria is temporally associated with reduction of the MMP and precedes AIF nuclear translocation followed by cell demise. MMP depolarization has been described with PARP-1-independent, caspase-independent AIF release (Kondo et al., 2010) in addition to initiating apoptosis (Kroemer et al., 1997; Green and Reed, 1998).

Fig. 13.

Schematic diagram depicting the mechanism of action of UCD38B. UCD38B binds to intracellular uPA, causing its translocation to perinuclear mitochondria and triggering a reduction in the mitochondrial membrane potential MMP. AIF is subsequently released from mitochondria and nuclearly translocated to cause caspase-independent necrosis. AIF-mediated necroptosis triggered by UCD38B appears to be independent of PARP activation or H2AX phosphorylation.

In U87 glioma cells, pretreatment with an irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor did not alter the antiglioma cytotoxicity of UCD38B. MDA231 breast cancer cells treated with UCD38B also demonstrate a similar caspase-independent cell death. Additionally, it was found that UCD38B does not kill cancer cells by autophagy or by calcium-mediated calpain activation (Leon et al., submitted manuscript). The electron micrographic studies of U87 glioma cancer cells treated with UCD38B demonstrated nuclear condensation, which is often triggered by AIF. AIF is present in intermembrane space of mitochondria under normal conditions. When cells are induced to undergo apoptosis, AIF is translocated into the nucleus triggering the cell death events (Cande et al., 2002). UCD38B treatment induced nuclear translocation of AIF in U87MG cells as demonstrated by immunocytological staining and by nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation studies. Furthermore, attenuating AIF protein expression by siRNA delayed and reduced glioma cytotoxicity by UCD38B. However, glioma cell death was not completely abrogated by siRNA of AIF. Caspase-3 was not activated by drug treatment when AIF was downregulated and no morphologic features of apoptosis were observed, suggesting that reduced AIF levels may be adequate to continue mediating the residual glioma cell death caused by UCD38B. Previous studies report that AIF interacts with H2AX, a histone family protein, and its phosphorylation on Ser139 is critical for caspase-independent programmed necrosis (Artus et al., 2010). We did not investigate the interactions of AIF and H2AX in this study. However, our data demonstrate that programmed necrosis initiated by UCD38B appears to be independent of phosphorylation of H2AX. To our knowledge, this is a novel observation indicating that UCD38B can trigger a necroptotic cancer cell death that is independent of γH2AX activation.

In summary, these studies indicate that 5′−benzylglycinyl-amiloride kills proliferating and nonproliferating glioma cells through the activation of a potentially novel programmed necrotic pathway that is a consequence of drug-induced mistrafficking of intracellular uPAS. This necroptotic pathway is mediated by AIF, independent of caspase and PARP-1 activation, and independent of H2AX phosphorylation.

Abbreviations

- 3-AB

3-aminobenzamide

- AIF

apoptosis-inducing factor

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- HGG

high-grade glioma

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- NHE1

type 1 sodium-proton exchanger

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- UCD38B

5′−benzylglycinyl-amiloride

- UCD74A

glycinyl-amiloride

- uPA

urokinase plasminogen activator

- uPAS

urokinase plasminogen activator system

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Pasupuleti, Leon, Carraway, Gorin.

Conducted experiments: Pasupuleti, Leon.

Performed data analysis: Pasupuleti, Leon, Gorin.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Pasupuleti, Gorin, Caraway.

Footnotes

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health [Grants NS040489 and NS060880].

F.G. is the founder of D3G, Inc. (Davis Drug Discovery Group), a California based biotech focused on the preclinical development of compounds for the treatment of primary and metastatic cancers.

References

- Amaravadi RK, Thompson CB. (2007) The roles of therapy-induced autophagy and necrosis in cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res 13:7271–7279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, Wang H, Koh DW, Sasaki M, Klaus JA, Otsuka T, Zhang Z, Koehler RC, et al. (2006) Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer is a death signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:18308–18313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprelikova O, Wood M, Tackett S, Chandramouli GVR, Barrett JC. (2006) Role of ETS transcription factors in the hypoxia-inducible factor-2 target gene selection. Cancer Res 66:5641–5647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artus C, Boujrad H, Bouharrour A, Brunelle MN, Hoos S, Yuste VJ, Lenormand P, Rousselle JC, Namane A, England P, et al. (2010) AIF promotes chromatinolysis and caspase-independent programmed necrosis by interacting with histone H2AX. EMBO J 29:1585–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baritaud M, Boujrad H, Lorenzo HK, Krantic S, Susin SA. (2010) Histone H2AX: The missing link in AIF-mediated caspase-independent programmed necrosis. Cell Cycle 9:3166–3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brat DJ, Castellano-Sanchez AA, Hunter SB, Pecot MJ, Cohen C, Hammond EH, Devi SN, Kaur B, Van Meir EG. (2004) Pseudopalisades in glioblastoma are hypoxic, express extracellular matrix proteases, and are formed by an actively migrating cell population. Cancer Res 64:920–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JC, Brown PD, O’Neill BP, Meyer FB, Wetmore CJ, Uhm JH. (2007) Central nervous system tumors. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1271–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candé C, Cohen I, Daugas E, Ravagnan L, Larochette N, Zamzami N, Kroemer G. (2002) Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF): a novel caspase-independent death effector released from mitochondria. Biochimie 84:215–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaitanya GV, Steven AJ, Babu PP. (2010) PARP-1 cleavage fragments: signatures of cell-death proteases in neurodegeneration. Cell Commun Signal 8:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossarizza A, Baccarani-Contri M, Kalashnikova G, Franceschi C. (1993) A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 197:40–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn IF, Black PM. (2003) The neurosurgeon as local oncologist: cellular and molecular neurosurgery in malignant glioma therapy. Neurosurgery 52:1411–1422, discussion 1422–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franovic A, Holterman CE, Payette J, Lee S. (2009) Human cancers converge at the HIF-2alpha oncogenic axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:21306–21311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cañero R, Trilla C, Pérez de Diego J, Díaz-Gil JJ, Cobo JM. (1999) Na+ :H+ exchange inhibition induces intracellular acidosis and differentially impairs cell growth and viability of human and rat hepatocarcinoma cells. Toxicol Lett 106:215–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golstein P, Kroemer G. (2007) Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem Sci 32:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu C-J, Diehl JA, Simon MC. (2007) HIF-2α promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell 11:335–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin F, Harley W, Schnier J, Lyeth B, Jue T. (2004) Perinecrotic glioma proliferation and metabolic profile within an intracerebral tumor xenograft. Acta Neuropathol 107:235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin F and Nantz M(2007) inventors, University of California, assignee. Amino acid and peptide conjugates of Amiloride and methods of use thereof. U.S. patent PCT/US2005/001564. 2005 Jan 21. [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC. (1998) Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281:1309–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley W, Floyd C, Dunn T, Zhang XD, Chen TY, Hegde M, Palandoken H, Nantz MH, Leon L, Carraway KL, 3rd, Lyeth B, Gorin FA. (2010) Dual inhibition of sodium-mediated proton and calcium efflux triggers non-apoptotic cell death in malignant gliomas. Brain Res 1363:159–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde M, Roscoe J, Cala P, Gorin F. (2004) Amiloride kills malignant glioma cells independent of its inhibition of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh MY, Lemos R, Jr, Liu X, Powis G. (2011) The hypoxia-associated factor switches cells from HIF-1α- to HIF-2α-dependent signaling promoting stem cell characteristics, aggressive tumor growth and invasion. Cancer Res 71:4015–4027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Obitsu S, Ohta S, Matsunami K, Otsuka H, Teshima R. (2010) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1-independent apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) release and cell death are induced by eleostearic acid and blocked by α-tocopherol and MEK inhibition. J Biol Chem 285:13079–13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Zamzami N, Susin SA. (1997) Mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Immunol Today 18:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamborn KR, Yung WK, Chang SM, Wen PY, Cloughesy TF, DeAngelis LM, Robins HI, Lieberman FS, Fine HA, Fink KL, et al. North American Brain Tumor Consortium (2008) Progression-free survival: an important end point in evaluating therapy for recurrent high-grade gliomas. Neuro-oncol 10:162–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey AP, Harley WR, Pasupuleti N, Gorin FA, Nantz MH. (2012) 2-Amidino analogs of glycine-amiloride conjugates: inhibitors of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22:2635–2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moubarak RS, Yuste VJ, Artus C, Bouharrour A, Greer PA, Menissier-de Murcia J, Susin SA. (2007) Sequential activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, calpains, and Bax is essential in apoptosis-inducing factor-mediated programmed necrosis. Mol Cell Biol 27:4844–4862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palandoken H, By K, Hegde M, Harley WR, Gorin FA, Nantz MH. (2005) Amiloride peptide conjugates: prodrugs for sodium-proton exchange inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312:961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert M, Steinbach JP, Supra P, Weller M. (2002) Modulation of growth and radiochemosensitivity of human malignant glioma cells by acidosis. Cancer 95:1113–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M, Harbeck N, Brünner N, Jänicke F, Meisner C, Mühlenweg B, Jansen H, Dorn J, Nitz U, Kantelhardt EJ, Thomssen C. (2011) Cancer therapy trials employing level-of-evidence-1 disease forecast cancer biomarkers uPA and its inhibitor PAI-1. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 11:617–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnier JB, Nishi K, Harley WR, Gorin FA. (2008) An acidic environment changes cyclin D1 localization and alters colony forming ability in gliomas. J Neurooncol 89:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks RL, Pool TB, Smith NKR, Cameron IL. (1983) Effects of amiloride on tumor growth and intracellular element content of tumor cells in vivo. Cancer Res 43:73–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talks KL, Turley H, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Harris AL. (2000) The expression and distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated macrophages. Am J Pathol 157:411–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulisse S, Baldini E, Sorrenti S, D’Armiento M. (2009) The urokinase plasminogen activator system: a target for anti-cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 9:32–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]