Abstract

Accumulated evidence indicates that ROS fluctuations play a critical role in cell division. Dividing plant cells rapidly respond to them. Experimental disturbance of ROS homeostasis affects: tubulin polymerization; PPB, mitotic spindle and phragmoplast assembly; nuclear envelope dynamics; chromosome separation and movement; cell plate formation. Dividing cells mainly accumulate at prophase and delay in passing through the successive cell division stages. Notably, many dividing root cells of the rhd2 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants, lacking the RHD2/AtRBOHC protein function, displayed aberrations, comparable to those induced by low ROS levels. Some protein molecules, playing key roles in signal transduction networks inducing ROS production, participate in cell division. NADPH oxidases and their regulators PLD, PI3K and ROP-GTPases, are involved in MT polymerization and organization. Cellular ROS oscillations function as messages rapidly transmitted through MAPK pathways inducing MAP activation, thus affecting MT dynamics and organization. RNS implication in cell division is also considered.

Keywords: ROS signaling, cytokinesis, tubulin paracrystals, macrotubules, microtubules, mitosis, reactive oxygen species

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are undesirable byproducts of the aerobic life.1 The most common between them are: the singlet oxygen, the superoxide anion, the hydroxyl radicals and the hydrogen peroxide. They are produced in several cell compartments, including mitochondria, chloroplasts, peroxisomes, as well as in the apoplast.2,3 Plant cells have developed astonishing abilities not only to manage the internal and external sources of ROS via enzymatic and non-enzymatic scavenging mechanisms, but also to use free radicals as signaling molecules.4 There is convincing evidence that ROS function as key regulators of plant development. They are implicated in a variety of biological processes such as root-hair and pollen tube growth, hormonal responses and biotic and abiotic stress responses.5-7 Moreover, ROS trigger signal transduction pathways and, even more, control gene expression.2

In animal cells, ROS are involved in cell proliferation regulating transition through specific cell cycle checkpoints.8 Similarly, plant cell cycle progression depends on redox sensing. ROS are able to modulate the activity of the cyclin dependent kinases.9,10 Moreover, apart from acting to protect plant cells from oxidative damage, antioxidants are also implicated in cell cycle control influencing specific cell cycle transitions. During different stages of the cell cycle, the levels of glutathione and ascorbate seem to fluctuate11 along with ROS levels.12,13

Despite the extensive information regarding ROS signaling in cell cycle regulation, the available knowledge on the relationship between ROS and plant cell mitosis and cytokinesis (cell division) is very limited. Plant cell division is performed by specific microtubule (MT) arrays characterized by extensive and continuous reorganization. Recent evidence revealed that ROS homeostasis is critical for plant cell division.14 In this article, the available knowledge on ROS implication in plant cell division and, particularly, in MT organization is reviewed. Moreover, the roles of proteins, which are key components of ROS signaling processes during plant cell division, are discussed.

ROS Homeostasis and Plant Cell Division

Experimental disturbance of ROS homeostasis in root-tips of Triticum turgidum and Arabidopsis thaliana deeply affects mitosis14 and cytokinesis. ROS imbalance caused significant delay in the transition from prophase to prometaphase, interfered with nuclear envelope dynamics, affected prometaphase and anaphase chromosome movement and delayed cell exit from telophase. Cytokinesis was also greatly affected. As a result, multinucleate or polyploid cells were formed. Notably, mitotic and cytokinetic aberrations were found by using menadione, a quinone that induces elevated ROS levels. The aberrations were very similar to those detected after treatment with diphenylene iodonium (DPI), an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, and N-acetyl cysteine, a ROS scavenger, which reduces ROS levels. These findings are strongly supported by data derived from the study of dividing root-tip cells of the rhd2 A. thaliana mutants, lacking the function of the RHD2/AtRBOHC protein that is differentially expressed in roots.15,16 The rhd2 plants exhibit short root hairs as well as shorter roots than the wild type.15 Definite rhd2 root cell types displayed aberrations comparable to those found after treatment with DPI.14 Some of them seem to be the outcome of misorganization and malfunction of the tubulin cytoskeleton involved in cell division.

Nuclear envelope dynamics

ROS interference with nuclear envelope dynamics was evidenced by the delayed breakdown of the nuclear envelope at late prophase and its delayed reconstitution at telophase.14 The affected cells were accumulated at the end of prophase, while their transition to prometaphase was highly delayed or even prevented. It is well known that cyclin dependent kinases are involved in phosphorylation of the lamin network, thus triggering nuclear envelope breakdown.17 Relying on the above and on ROS interference with the activity of cyclin dependent kinases,9 the nuclear envelope persistence in late prophase plant cells affected by ROS modulators, can be correlated with lamin malfunction induced by ROS imbalance. Recently, it has been also found that in animal cells oxidative stress induces lamin accumulation.18

Alternatively, it must be considered that ROS homeostasis interferes with Ca2+ homeostasis15 and that nuclear envelope disintegration and reconstitution require definite local Ca2+ oscillations.19 Therefore, it might be suggested that the aberrant nuclear envelope behavior is caused by the imbalance of cytoplasmic Ca2+ homeostasis that is induced by loss of ROS homeostasis. ROS can activate Ca2+ channels in roots,15 while oxidative stress is accompanied by Ca2+ release in cytosol.20

Organization of tubulin cytoskeleton

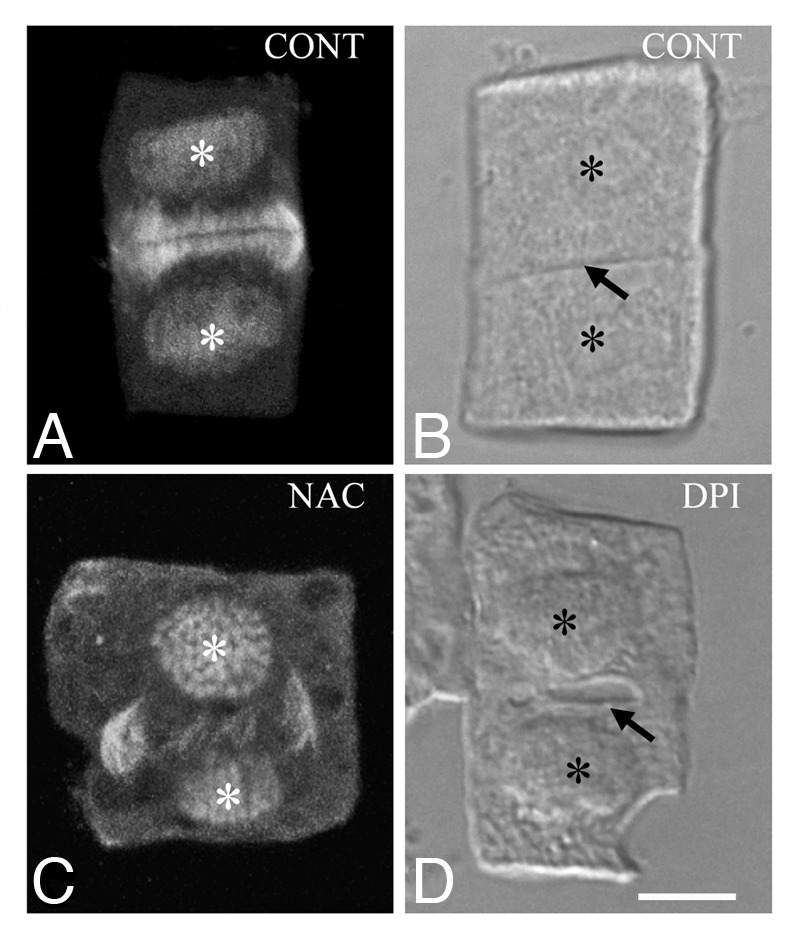

ROS imbalance causes multiple effects on tubulin cytoskeleton in dividing root-tip cells,14 which are structurally expressed as follows: (1) Preprophase band (PPB) formation was prevented in many preprophase/prophase cells, while when it was present it was appeared highly aberrant, consisting of atypical tubulin polymers. (2) The perinuclear tubulin polymer formation in prophase cells was inhibited. In case of their presence, they failed to assemble a bipolar prophase spindle. (3) The metaphase and anaphase spindle organization was also perturbed. These mitotic spindles displayed tubulin strands randomly oriented incapable to form bipolar systems. (4) The phragmoplast, made of atypical tubulin polymers, was aberrant, and its expansion toward cell cortex was delayed (Fig. 1C; cf. Fig. 1A). Consequently, in many affected cytokinetic cells the cell plate was absent or highly atypical (Fig. 1D; cf. Fig. 1B). Abnormalities in spindle and phragmoplast organization may be attributed to the replacement of MTs by atypical tubulin polymers.14 A more detailed discussion on atypical tubulin polymer formation upon ROS imbalance is presented below.

Figure 1. Cytokinetic control (A and B) and treated with ROS modulators (C and D) T. turgidum root-tip cells as they appear after tubulin immunolabeling (A and C) and DIC optics (B and D). The asterisks mark the daughter nuclei and the arrows point to cell plates. Aberrant phragmoplast expansion follows treatment with N-acetyl cysteine (C; cf. A), while a dilated cell plate (D; cf. B) forms in the presence of diphenylene iodonium. Treatments: (C) NAC 250 μM, 1 h; (D) DPI 25 μM, 1 h. Bar: 10 μm.

Concerning the absence of perinuclear tubulin polymers in prophase cells, it might be suggested that the perinuclear MT-organizing center activation is affected by the presence of ROS modulators. AtTPX2 is a protein, which seems to be implicated in the perinuclear MT-organizing center activation. It is believed that, after its transport from nucleus into cytoplasm, this protein is phosphorylated by aurora kinases.21 In animal cells, ROS are implicated in the activation of the α-aurora kinase. The phosphorylated form of this kinase is absent from the centrosome of DPI treated animal cells.22,23 Then, it may be extrapolated that cells affected by ROS modulators aurora kinases fail in phosphorylating the AtTPX2 protein. In A. thaliana, α-aurora kinases have been also implicated in the determination of the cell division plane.24 Therefore, ROS imbalance, modifying the activity of aurora kinases, might prevent PPB formation in many affected cells.

Chromosome movement

ROS modulators interfere with the metaphase chromosome alignment on the equatorial spindle plane as well as with the anaphase chromosome movement.14 This may be due to the inability of the affected cells to assemble functional spindles and to inhibition of chromatid separation. Besides, the latter process depends on the action of proteases named separases. Prior to chromatid segregation, separases are bound to a small protein, the securin that inhibits their action. The anaphase promoting complex is responsible for the liberation of separases, which cleave the cohesin complex holding daughter chromatids together.25,26 The function of separases is well known in dividing animal cells, whereas recent data indicate their participation in plant cell division.26,27 In animal cells, ROS overproduction prevents the anaphase chromosome separation. Treatment with hydrogen peroxide inhibits anaphase promoting complex and subsequently blocks the separase-securin disassociation, delaying cell cycle progress.25 Moreover, in animal as well as in plant cells aurora kinase is implicated in chromosome segregation.28 At least in animal cells experiencing low ROS levels, α-aurora kinase expression is affected.22,23 Besides, the assembly of non-functional mitotic spindles and phragmoplasts can be explained by the presence of atypical tubulin polymers, which is induced by the loss of ROS homeostasis.14 Macrotubules (tubulin tubules exhibiting diameter greater than that of MTs) form in low ROS levels and tubulin paracrystals in elevated ones (see below).

Imbalanced ROS Levels and Atypical Tubulin Polymer Formation

In animal cells, the loss of ROS homeostasis affects MT cytoskeleton. Treatment of Rat1 fibroblasts with DPI, which leads to low ROS production, caused disassembly of tyrosinated MTs and their replacement by detyrosinated ones.29 Besides, oxidative stress applied on human cortical neuron cell lines, induced MT loss, which was followed by MT rearrangement.30

In plants, the first information on the functional relationship between ROS and MT cytoskeleton was derived from the study of cellular responses to biotic or abiotic stress. Salinity stress followed by ROS overproduction31 led to MT depolymerization and subsequently to MT reorganization, which is probably required in order for cells to withstand salt stress.32 Furthermore, Verticillum dahliae toxins applied on A. thaliana leaves induced a rapid increase of ROS levels, which in turn resulted in MT disruption.33 Interestingly, treatment of A. thaliana leaves with DPI that reduces ROS levels alleviates the effects of V. dahliae toxins on the MT cytoskeleton. In addition, Nick34 noted that biotic stress perception depends on MTs and is also mediated by RBOHC (respiratory burst oxidase homolog), the plant homolog of the NADPH oxidase that upon activation catalyzes ROS production in the apoplast.

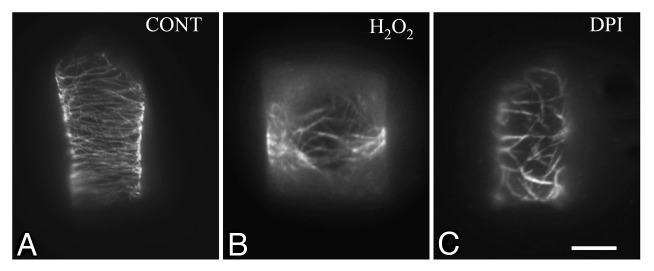

In dividing plant cells, the serious effects of the experimentally induced ROS homeostasis disruption on MT cytoskeleton were monitored in root-tip cells of the angiosperms T. turgidum and A. thaliana.14 Under either low or increased ROS levels, MTs coexisted with atypical tubulin polymers. In DPI and N-acetyl cysteine treated cells, the majority of tubulin polymers were macrotubules, while in menadione treated cells, tubulin cytoskeleton was mainly consisted of tubulin paracrystals.14 Unlikely, the oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide mimics the effects of DPI. In root-tip cells of T. turgidum, treatment with hydrogen peroxide resulted in replacement of MTs by tubulin strands (Fig. 2A; cf. Fig. 2B) similar to those observed in DPI treated cells (Fig. 2B; cf. Fig. 2C). This may be attributed to the mode by which hydrogen peroxide exerts its function. Contrary to other oxidative stress generators,35 the exogenously applied hydrogen peroxide mainly accumulates in the apoplast and diffuses into cytoplasm through the plasma membrane.36

Figure 2. Control (A) and treated with hydrogen peroxide (B) and diphenylene iodonium (DPI) (C) T. turgidum root-tip cells as they appear after tubulin immunolabeling. The effects of hydrogen peroxide treatment on tubulin cytoskeleton (B; cf. A) are comparable to those induced by DPI (C; cf. B). Treatments: (B) H2O2 4 mM, 1 h; (C) DPI 25 μM, 1 h. Bar: 10 μm.

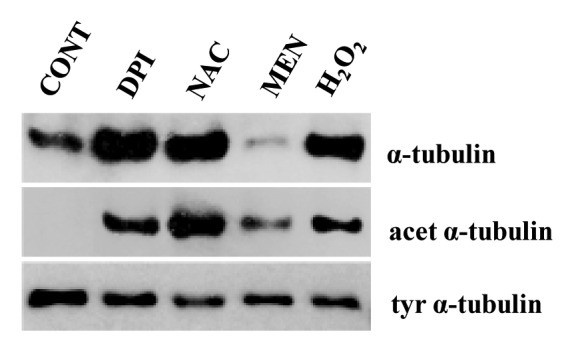

Western blotting analysis showed that loss of ROS homeostasis disturbs the levels of α-tubulin in roots of T. turgidum. Treatment with DPI, N-acetyl cysteine and hydrogen peroxide caused increase of α-tubulin levels, while on the contrary menadione treatment resulted in reduced α-tubulin levels (Fig. 3). This implies a direct effect of increased free radicals on α-tubulin (see also ref. 30). Similarly, the oxidative stress generated by quinones in human brain cell extracts reduced significantly the levels of β-tubulin.37

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of α-tubulin, acetylated and tyrosinated α-tubulin levels after treatment of T. turgidum roots with ROS modulators for 1 h. Twenty micrograms of total protein extract were loaded per well in every case. Protein amount was assessed with Bradford reagent (CONT, dH2O; DPI, diphenylene iodonium 25 μM; ΝΑC, N-acetyl cysteine 250 μM; MEN, menadione 25 μM; H2O2 4mM).

Moreover, immunoblotting revealed that treatment of roots with ROS modulators induces α-tubulin acetylation as well as a slight decrease of the tyrosinated α-tubulin levels (Fig. 3). Since acetylated tubulin is absent from the control roots (Fig. 3), it might be suggested that macrotubules and tubulin paracrystals consist of or contain acetylated tubulin. These data strengthen previous ones derived by indirect immunofluorescence, which showed the presence of acetylated tubulin in the atypical tubulin polymers.14 During oxidative stress, tubulin acetylation may represent a cell response, necessary to protect tubulin from the elevated ROS levels.

As far as MT disappearance associated with the disturbance of ROS homeostasis is concerned, several hypotheses can be formulated. Thus, the increased ROS levels may lead to direct MT disruption through: (A) elevation of Ca2+ levels,14,32 (B) oxidative modifications of tubulin,37 and/or (C) inactivation of MT-associated proteins (MAPs).33 However, the possibility that low ROS levels induce MT disintegration by interference with MT dynamic instability cannot be also excluded.14 It has been supported that DPI destructs the unstable MTs of Rat1 fibroblasts by uncoupling their minus end from centrosome, thus triggering MT disintegration.29

Signaling Mechanisms Inducing ROS Production: The Crucial Role of the NADPH Oxidase

Ca2+ levels have been implicated in the activation of NADPH oxidases,16 enzymes playing a key role in ROS signaling. They are considered as enzymes involved in “deliberating” ROS production.38 These membrane-bound enzymes transfer electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen generating superoxide anions in the apoplast. Superoxide anions could react with H2O to produce hydrogen peroxide.39 Several indications suggest that ROS production catalyzed by NADPH oxidase influences MT organization. Some of the protein molecules involved in regulation of the NADPH oxidases have been also implicated in MT organization. Among others, proteins that activate NADPH oxidases are phospholipase D (PLD), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and ROP-GTPases. A similar model describing the control of the actin cytoskeleton in root-hair tip growth has already been proposed by Samaj et al.40 The role of these proteins during cell division is discussed below.

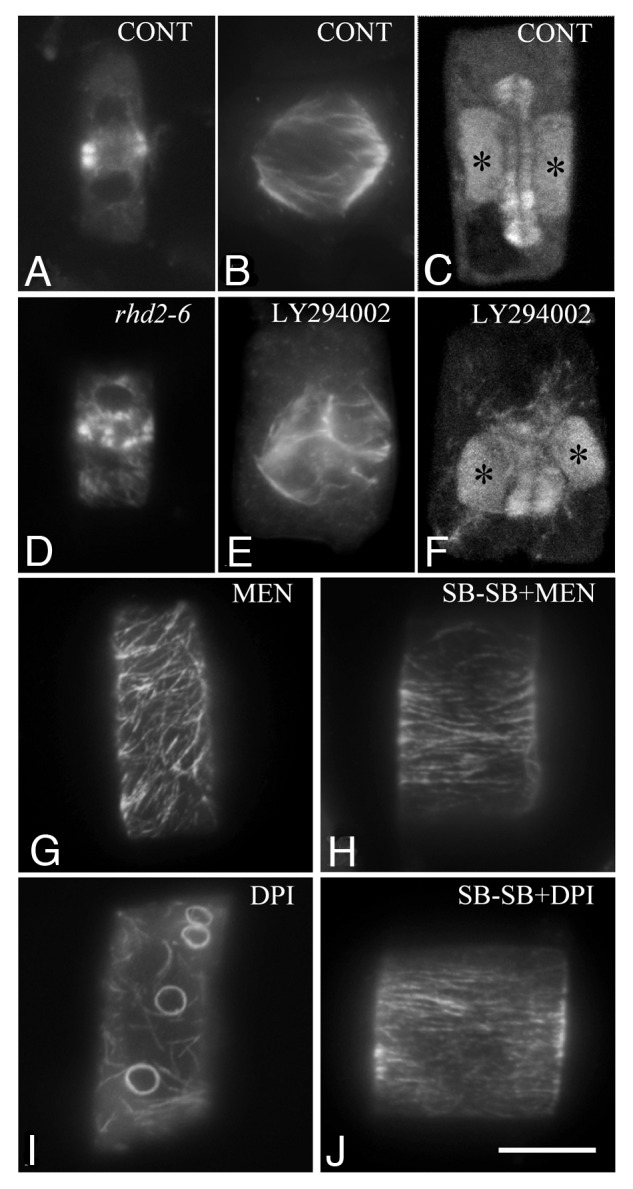

Direct evidence, which favors the idea that ROS production by NADPH oxidases is important for the organization of tubulin cytoskeleton and cell division, has been derived from the study of dividing root-tip cells of the rhd2-5 and rhd2-6 A. thaliana mutants.14 They lack the RBOHC, one of the ten A. thaliana NADPH oxidases, which is differentially expressed in roots.16 Specific root cell types of these mutants, i.e., root-hairs, rhizodermal and endodermal cells, exhibited arrays of tubulin polymers consisted of macrotubules and MTs. The percentage of macrotubules varied among different root cell types,14 but the pattern of their appearance was in accordance with the pattern of expression of the RHD2 protein in control A. thaliana roots.15 The tubulin cytoskeleton defects displayed by these mutants can be safely attributed to the lack of the NADPH oxidase RBOHC and explain the mitotic14 and cytokinetic disorders (Fig. 4D; cf. Fig. 4A) found in many cells. This strengthens findings obtained after treatment of root-tip cells with DPI and shows that the disturbance of the tubulin cytoskeleton is due to the reduction of ROS production.

Figure 4.A. thaliana (A and D) and T. turgidum (B, C and E--J) root-tip cells as they appear after tubulin immunolocalization. (A and D) Cytokinetic cells from wild type (A) and rhd2-6 (D) A. thaliana roots. Note the differences in phragmoplast organization. (B, C, E and F) Prometaphase (B and E) and cytokinetic (C and F) control (B and C) and treated cells with the specific inhibitor of PI3K LY294002 (E and F). The asterisks mark the daughter nuclei. Treatment: LY294002 50 μM, 2 h. (G and I) Atypical tubulin polymers appeared in cells after treatment with ROS modulators (compare Fig. 2A). Treatments: (G) MEN, menadione 25 μM, 1 h; (I) DPI, diphenylene iodonium 25 μM, 1 h. (H and J) The intensity of atypical tubulin polymer formation is clearly alleviated in the presence of the p38 MAPK specific inhibitor SB203580 (compare G and I). Treatments: (H) SB 10 μM, 30 min + SB plus MEN 25 μM, 1 h; (J) SB 10 μM, 30 min + SB plus DPI 25 μM, 1 h. Bar: 10μM.

Phosholipase D

PLDs are membrane phosphodiesterases involved in ROS responses. They also trigger ROS production.41 In guard cells, PLDα1 generates phosphatidic acid (PA) in response to abscisic acid and contributes to ROS mediated stomatal closure.42 PA activates the main NADPH oxidases of guard cells, RBOHD and RBOHF. Moreover, PA binds directly to RBOHs resulting in their activation.38,42 Besides, a significant amount of experimental work shows that, in plant cells, PA levels affect MT organization. For example, 1-butanol, which functions as substrate of PLD and results in inhibition of PLD derived PA production, disrupts MT arrays and blocks cell division in Silvetia compressa zygotes.43 In addition, 1-butanol induces extensive MT depolymerization in BY-2 cells and A. thaliana seedlings44,45 and affects tubulin cytoskeleton in plasmolyzed root-tip cells of T. turgidum.46 Therefore, it is tempting to suggest that PLD, among others, influences tubulin cytoskeleton, via the NADPH oxidase dependent ROS generation.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is a phosphoinositide generated by PI3K, which is involved in ROS production.47 In animal cells, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate seems to stimulate ROS production by direct binding to the PX domain of the NADPH oxidase.48 In plants, this enzyme is required for root-hair growth. PI3K inhibition by its specific inhibitor LY294002 prevented tip growth in root-hairs and simultaneously reduced ROS production.49 However, RBOHC is required exclusively for ROS generation at the onset of root-hair elongation. Other ROS generators seem to be implicated in PI3K induced ROS production at the late stages of root-hair elongation.49

Treatment of T. turgidum and A. thaliana root-tips with LY294002 disturbed the organization of tubulin cytoskeleton (Fig. 4E and F; cf. Fig. 4B and C) and seriously affected cell division. The effects were very similar to those recorded after DPI treatment. These findings allow the hypothesis that ROS generation, which is stimulated by the action of PI3K in dividing cells, participates in ROS homeostasis mechanisms. However, at present we are not in position to estimate RBOHC contribution in ROS production driven by PI3K.

Rho-related proteins

In plants, the ROP-GTPases seem to function as molecular rheostats in sensing oxygen deprivation.50 These proteins are involved in RBOH activation. For example, in rice NADPH oxidase activation is mediated by binding to Rac GTPase.51 On the other hand, kinesins and MAPs are considered as effector molecules of Rho-related GTPases, thus regulating MT organization and dynamics.52,53 However, it remains unclear whether cytoskeleton signaling via ROP-GTPases includes ROS signaling (see also ref. 52).

ROS Signaling Transduction, Organization of Tubulin Cytoskeleton and Cell Division

MAPs

Recent data suggest that MAP65 is involved in the formation of atypical tubulin polymers induced by ROS modulators.14 Immunolocalization of MAP65-1 proteins in A. thaliana root-tips revealed the presence of MAP65-1 on macrotubules and in tubulin paracrystals. Moreover, ΜΑP65 proteins participate in the assembly of tubulin paracrystals formed after colchicine treatment.54 MAP65 is activated after phosphorylation by MPK4 and MPK6. MPK4 and MPK6 are key components in ROS signaling transduction.55 Therefore, it might be suggested that MAP65 activation is regulated, at least in part by ROS levels, to promote MT-bundling in normal conditions and the atypical tubulin polymer formation under disturbed ROS levels. Consequently, this protein seems to respond to changes of MAPK signaling induced by ROS levels.

MAPKs

MPK4 is a MAPK involved in abiotic signal perception and its action as ROS responsive MAPK has been well appreciated.55 In addition, MPK4 co-localized with MT arrays in A. thaliana root cells in a pattern similar to that of MAP65-1.56 MPK4 plays a role in the transition from mitosis to cytokinesis, whereas the mpk4 mutant exhibits aberrant spindles and phragmoplasts.57 Therefore, MPK4, apart from the abiotic signal transduction, appears to be implicated in sensing alterations in ROS levels as well as in the regulation of MT organization during plant cell division. MPK4 activation depends on its phosphorylation by MEKK1. This MAPKKK is involved in the expression of numerous genes implicated in cellular redox control.58 Relation between MEKK1 and MPK4 dependent MT regulation has been recently described.59

In animal cells, the p38 MAPK is a stress responsive MAPK, which is upregulated under oxidative stress and downregulated when ROS levels decrease.60,61 A p46 MAPK, displaying immunological and pharmacological properties similar to those of the p38 MAPK, is activated in plants experiencing osmotic stress. Its phosphorylation seems to induce changes in tubulin cytoskeleton under hyperosmotic conditions, stimulating macrotubule formation.62 Considering that under disturbed ROS levels the root-tip cells assemble atypical tubulin polymers,14 it was investigated whether the p38-like kinase (p46 MAPK) is involved in the formation of these tubulin polymers.

In this direction, the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 was applied together with drugs creating oxidative stress on T. turgidum roots. In presence of the inhibitor, the intensity of the atypical tubulin polymer appearance was alleviated (Fig. 4H; cf. Fig. 4G). This is in accordance with the hypothesis that p38 like MAPK is activated in plants experiencing oxidative stress and mediates the formation of atypical tubulin polymers, probably to prevent tubulin damage by oxidative modification.14 Moreover, application of the SB203580 together with DPI or N-acetyl cysteine also seemed to alleviate atypical tubulin polymer assembly in root-tip cells (Fig. 4J; cf. Fig. 4I). Therefore, in cells treated with ROS modulators in the presence of the p38 MAPK inhibitor, the organization of the tubulin cytoskeleton is comparable to that of the untreated cells (Figs. 4H and J; cf. Fig. 2A). This was not expected since p38 kinase, at least in animal cells, is activated under oxidative stress and is downregulated under low ROS levels.60,61

Reactive Nitrogen Species

Emerging evidence reveals that apart from ROS, the reactive nitrogen species (RNS) play a particular role in cell cycle regulation.63,64 In several cases, ROS act cooperatively with RNS to stimulate responses through the same signaling cascades.65 They can also co-interact, e.g., nitric oxide anion can interact with superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite.66 Nitric oxide is produced by non enzymatic mechanisms in the apoplast or inside the cells by the activation of nitric oxide synthase putative enzymes.67 RNS are produced simultaneously with ROS in biotic or abiotic stress conditions. The role of RNS in MT cytoskeleton has been recently reviewed.68 As in the case of ROS, nitric oxide also induces tubulin post transcriptional modifications (tyrosine nitration). Nitric oxide donors and scavengers regulate MT organization. In particular, RNS homeostasis seems to be critical for the proper cortical MT formation. Therefore, studies concerning ROS, MT organization and cell division should also consider RNS involvement in the future.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

ROS signaling triggered “a new wave” of research in plant cells.4 Among others, information accumulated so far allow the hypothesis that ROS are molecules functioning as signaling components during cell division, through complex signaling pathways. The fluctuations of oxidants and antioxidants during cell division11-13 support ROS implication in this process, while ROS imbalance induces formation of atypical tubulin polymers.14

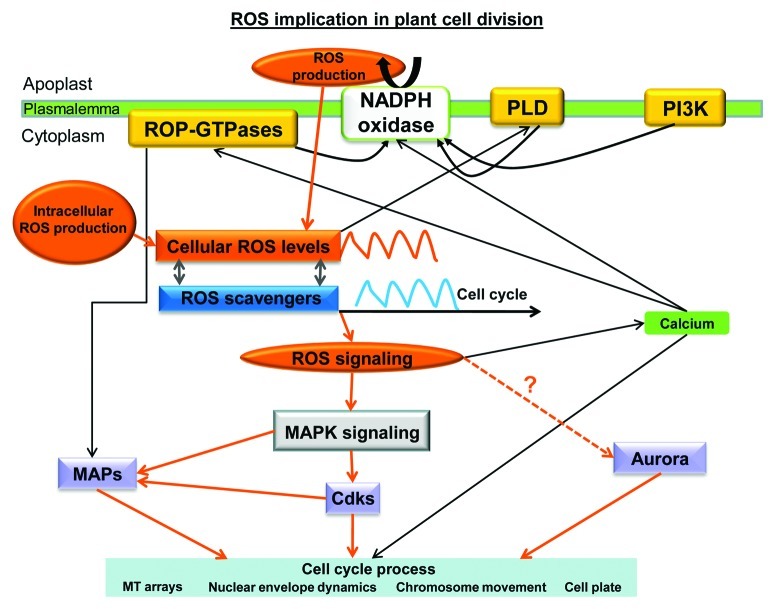

ROS production seems to be induced by environmental, hormonal or other intercellular signals. NADPH oxidase releases ROS in the apoplast that enter into the cytoplasm. ROS production by NADPH oxidases is triggered by PLD, PI3K or ROP-GTPases. Intracellular ROS level oscillations keep pace with respective antioxidant oscillations. Subsequently, ROS acting as signaling molecules contribute to the establishment of Ca2+ gradients and participate in the control of regulatory proteins such as cyclin dependent kinases, MAPs and possibly aurora kinases. Thus, ROS are implicated in the regulation of cell cycle progress, organization of MT arrays, nuclear envelope dynamics and cell plate formation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Simplified diagram describing probable routes of ROS implication in cell division. Abbreviations used: Aurora, Aurora kinases; Cdks, cyclin dependent kinases; MAPs, microtubule associated proteins; MAPK, mitogen activated protein kinase; NADPH oxidase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PLD, phospholipase D; ROP-GTPases, rho-related GTPases of plants; ROS, reactive oxygen species

However, further work is needed to elucidate what exactly ROS do and how. Particular attention should also be paid to identify the role of each type of ROS in cell division, the sites of their production, as well as their targets. In this direction, examination of MT organization in mutants lacking proteins involved in ROS production and scavenging would also improve the existing knowledge on the relation between ROS and plant cell division. Moreover, further transcriptome and proteome analysis under conditions creating low or elevated ROS levels would reveal missing links in the effects of ROS on MTs, whereas analysis using oxyblot technique could show oxidative modifications in several proteins induced by ROS. In any case, experiments with ROS modulators should be carefully interpreted, since ROS imbalance may cause cell damage.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr H. Quader (Biocenter Klein Flottbek, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) for the kind offer of the LY294002. The present study was financed by the University of Athens.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DPI

diphenylene iodonium

- MAP

microtubule associated protein

- MT

microtubule

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PLD

phospholipase D

- PPB

preprophase band

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RBOHC

respiratory burst oxidase homolog C

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/20530

References

- 1.Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Gollery M, Van Breusegem F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:490–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller IM, Sweetlove LJ. ROS signalling--specificity is required. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:370–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Suzuki N, Miller G, Tognetti VB, Vandepoele K, et al. ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:300–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller G, Shulaev V, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol Plant. 2008;133:481–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson S, Gilroy S. ROS in plant development. Physiol Plant. 2010;138:384–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres MA. ROS in biotic interactions. Physiol Plant. 2010;138:414–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burhans WC, Heintz NH. The cell cycle is a redox cycle: linking phase-specific targets to cell fate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1282–93. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichheld J-P, Vernoux T, Lardon F, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Specific checkpoints regulate plant cell cycle progression in response to oxidative stress. Plant J. 1999;17:647–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fehér A, Otvös K, Pasternak TP, Szandtner AP. The involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cell cycle activation (G(0)-to-G(1) transition) of plant cells. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:823–6. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.10.5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potters G, De Gara L, Asard H, Horemans N. Ascorbate and glutathione: guardians of the cell cycle, partners in crime? Plant Physiol Biochem. 2002;40:537–48. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(02)01414-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon SG, Goswami PC. A redox cycle within the cell cycle: ring in the old with the new. Oncogene. 2007;26:1101–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vivancos PD, Dong Y, Ziegler K, Markovic J, Pallardó FV, Pellny TK, et al. Recruitment of glutathione into the nucleus during cell proliferation adjusts whole-cell redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana and lowers the oxidative defence shield. Plant J. 2010;64:825–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livanos P, Galatis B, Quader H, Apostolakos P. Disturbance of reactive oxygen species homeostasis induces atypical tubulin polymer formation and affects mitosis in root-tip cells of Triticum turgidum and Arabidopsis thaliana. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2012;69:1–21. doi: 10.1002/cm.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foreman J, Demidchik V, Bothwell JHF, Mylona P, Miedema H, Torres MA, et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature. 2003;422:442–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeda S, Gapper C, Kaya H, Bell E, Kuchitsu K, Dolan L. Local positive feedback regulation determines cell shape in root hair cells. Science. 2008;319:1241–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1152505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans DE, Shvedunova M, Graumann K. The nuclear envelope in the plant cell cycle: structure, function and regulation. Ann Bot. 2011;107:1111–8. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barascu A, Le Chalony C, Pennarun G, Genet D, Imam N, Lopez B, et al. Oxidative stress induces an ATM-independent senescence pathway through p38 MAPK-mediated lamin B1 accumulation. EMBO J. 2012;31:1080–94. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hepler PK. The role of calcium in cell division. Cell Calcium. 1994;16:322–30. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rentel MC, Knight MR. Oxidative stress-induced calcium signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1471–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.042663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vos JW, Pieuchot L, Evrard J-L, Janski N, Bergdoll M, de Ronde D, et al. The plant TPX2 protein regulates prospindle assembly before nuclear envelope breakdown. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2783–97. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scaife RM. G2 cell cycle arrest, down-regulation of cyclin B, and induction of mitotic catastrophe by the flavoprotein inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1229–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scaife RM. Selective and irreversible cell cycle inhibition by diphenyleneiodonium. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:876–84. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Damme D, De Rybel B, Gudesblat G, Demidov D, Grunewald W, De Smet I, et al. Arabidopsis α Aurora kinases function in formative cell division plane orientation. Plant Cell. 2011;23:4013–24. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang T-S, Jeong W, Lee D-Y, Cho C-S, Rhee SG. The RING-H2-finger protein APC11 as a target of hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu S, Scheible W-R, Schindelasch D, Van Den Daele H, De Veylder L, Baskin TI. A conditional mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana separase induces chromosome non-disjunction, aberrant morphogenesis and cyclin B1;1 stability. Development. 2010;137:953–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.041939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moschou PN, Bozhkov PV. Separases: biochemistry and function. Physiol Plant. 2012;145:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurihara D, Matsunaga S, Uchiyama S, Fukui K. Live cell imaging reveals plant aurora kinase has dual roles during mitosis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1256–61. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaife RM. Microtubule disassembly and inhibition of mitosis by a novel synthetic pharmacophore. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:102–14. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allani PK, Sum T, Bhansali SG, Mukherjee SK, Sonee M. A comparative study of the effect of oxidative stress on the cytoskeleton in human cortical neurons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;196:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:453–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Li J, Yuan M. Salt tolerance requires cortical microtubule reorganization in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1534–47. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao L-L, Zhou Q, Pei B-L, Li Y-Z. Hydrogen peroxide modulates the dynamic microtubule cytoskeleton during the defence responses to Verticillium dahliae toxins in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:1586–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nick P. Microtubules and the tax payer. Protoplasma 2011; doi: 10.1007/s00709- 011-0339-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford: Clarendon Press 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan X-Y, Liu J-Y. Comparative proteomics analysis reveals an intimate protein network provoked by hydrogen peroxide stress in rice seedling leaves. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1469–88. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700488-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santa-María I, Smith MA, Perry G, Herńndez F, Avila J, Moreno FJ. Effect of quinones on microtubule polymerization: a link between oxidative stress and cytoskeletal alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005; 1740:472-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Marino D, Dunand C, Puppo A, Pauly N. A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sagi M, Fluhr R. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:336–40. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Šamaj J, Baluška F, Menzel D. New signalling molecules regulating root hair tip growth. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, Yu L, Zhang Y, Zhang X. Phospholipase D in the signaling networks of plant response to abscisic acid and reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005; 1736:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Zhang Y, Zhu H, Zhang Q, Li M, Yan M, Wang R, et al. Phospholipase Dα1 and phosphatidic acid regulate NADPH oxidase activity and production of reactive oxygen species in ABA-mediated stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;218:2357–77. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters NT, Logan KO, Miller AC, Kropf DL. Phospholipase D signaling regulates microtubule organization in the fucoid alga Silvetia compressa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1764–74. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirase A, Hamada T, Itoh TJ, Shimmen T, Sonobe S. n-Butanol induces depolymerization of microtubules in vivo and in vitro. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1004–9. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motes CM, Pechter P, Yoo CM, Wang Y-S, Chapman KD, Blancaflor EB. Differential effects of two phospholipase D inhibitors, 1-butanol and N-acylethanolamine, on in vivo cytoskeletal organization and Arabidopsis seedling growth. Protoplasma. 2005;226:109–23. doi: 10.1007/s00709-005-0124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komis G, Quader H, Galatis B, Apostolakos P. Macrotubule-dependent protoplast volume regulation in plasmolysed root-tip cells of Triticum turgidum: involvement of phospholipase D. New Phytol. 2006;171:737–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joo JH, Yoo HJ, Hwang I, Lee JS, Nam KH, Bae YS. Auxin-induced reactive oxygen species production requires the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellson CD, Gobert-Gosse S, Anderson KE, Davidson K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. PtdIns(3)P regulates the neutrophil oxidase complex by binding to the PX domain of p40(phox) Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:679–82. doi: 10.1038/35083076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee Y, Bak G, Choi Y, Chuang W-I, Cho H-T, Lee Y. Roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in root hair growth. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:624–35. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nibau C, Wu HM, Cheung AY. RAC/ROP GTPases: ‘hubs’ for signal integration and diversification in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong HL, Pinontoan R, Hayashi K, Tabata R, Yaeno T, Hasegawa K, et al. Regulation of rice NADPH oxidase by binding of Rac GTPase to its N-terminal extension. Plant Cell. 2007;19:4022–34. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu Y. ROP GTPases and the cytoskeleton. In: Yalovsky S, Baluška F, Jones A. eds. Integrated G proteins signaling in plants. Spinger-Verlag Heidelberg 2010; 91-104. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mucha E, Fricke I, Schaefer A, Wittinghofer A, Berken A. Rho proteins of plants--functional cycle and regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:934–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panteris E, Komis G, Adamakis I-DS, Šamaj J, Bosabalidis AM. MAP65 in tubulin/colchicine paracrystals of Vigna sinensis root cells: possible role in the assembly and stabilization of atypical tubulin polymers. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:152–60. doi: 10.1002/cm.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez MC, Petersen M, Mundy J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:621–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beck M, Komis G, Müller J, Menzel D, Šamaj J. Arabidopsis homologs of nucleus- and phragmoplast-localized kinase 2 and 3 and mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 are essential for microtubule organization. Plant Cell. 2010;22:755–71. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck M, Komis G, Ziemann A, Menzel D, Šamaj J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 is involved in the regulation of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubule transitions in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2011;189:1069–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakagami H, Soukupová H, Schikora A, Zárský V, Hirt H. A Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase mediates reactive oxygen species homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38697–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Komis G, Illés P, Beck M, Šamaj J. Microtubules and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurata S-i. Selective activation of p38 MAPK cascade and mitotic arrest caused by low level oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23413–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gaitanaki C, Papatriantafyllou M, Stathopoulou K, Beis I. Effects of various oxidants and antioxidants on the p38-MAPK signalling pathway in the perfused amphibian heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;291:107–17. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komis G, Apostolakos P, Gaitanaki C, Galatis B. Hyperosmotically induced accumulation of a phosphorylated p38-like MAPK involved in protoplast volume regulation of plasmolyzed wheat root cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otvös K, Pasternak TP, Miskolczi P, Domoki M, Dorjgotov D, Szűcs A, et al. Nitric oxide is required for, and promotes auxin-mediated activation of, cell division and embryogenic cell formation but does not influence cell cycle progression in alfalfa cell cultures. Plant J. 2005;43:849–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Correa-Aragunde N, Graziano M, Chevalier C, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide modulates the expression of cell cycle regulatory genes during lateral root formation in tomato. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:581–8. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Molassiotis A, Fotopoulos V. Oxidative and nitrosative signaling in plants: two branches in the same tree? Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:210–4. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.2.14878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moreau M, Lindermayr C, Durner J, Klessig DF. NO synthesis and signaling in plants--where do we stand? Physiol Plant. 2010;138:372–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stöhr C, Stremlau S. Formation and possible roles of nitric oxide in plant roots. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:463–70. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yemets AI, Krasylenko YA, Lytvyn DI, Sheremet YA, Blume YB. Nitric oxide signalling via cytoskeleton in plants. Plant Sci. 2011;181:545–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]