Abstract

An important player in actin remodeling is the actin depolymerizing factor (ADF) which increases actin filament treadmilling rates. Previously, we had prepared fluorescent protein fusions of two Arabidopsis pollen specific ADFs, ADF7 and ADF10. These had enabled us to determine the temporal expression patterns and subcellular localization of these proteins during male gametophyte development. Here we generated stable transformants containing both chimeric genes allowing for simultaneous imaging and direct comparison. One of the striking differences between the two proteins was the localization profile in the growing pollen tube apex. Whereas ADF10 was associated with the filamentous actin array forming the subapical actin fringe, ADF7 was present in the same cytoplasmic region, but in diffuse form. This suggests that ADF7 is involved in the high actin turnover that is likely to occur in the fringe by continuously and efficiently depolymerizing filamentous actin and supplying monomeric actin to the advancing end of the fringe. The possibility to visualize both of these pollen-specific ADFs simultaneously opens avenues for future research into the regulatory function of actin binding proteins in pollen.

Keywords: ADF, actin depolymerizing factor, actin, pollen tube

Expansive growth in plant cells relies on the spatially and temporally controlled delivery of cell wall material to the expanding wall. In no cell does this process occur as quickly and exquisitely fine-tuned as in the elongating pollen tube. This protuberance formed by the male gametophyte, the pollen, upon contact with a receptive flower, is one of the fastest growing cells in the plant kingdom. The targeted delivery of cell wall components such as pectins and hemicelluloses to the growing apex determines the diameter, speed and orientation of this rapidly expanding, perfectly cylindrical cell.1-4 The delivery process is orchestrated by the actin cytoskeleton, which guides secretory vesicles toward the site of exocytosis in a myosin-mediated process. The actin cytoskeleton in the pollen tube displays a characteristic configuration with thicker bundles in the shank and a finer fringe-shaped structure adjacent to the apex.5 The dynamics of actin filaments within this fringe is crucial for pollen tube functioning as is readily demonstrated by pharmacological destabilization6-8 and altered expression levels of actin binding proteins.9,10 Fine tuning of actin polymerization in the fringe is likely the key regulatory mechanism that allows pollen tubes to rapidly change their growth direction in response to a directional trigger.1

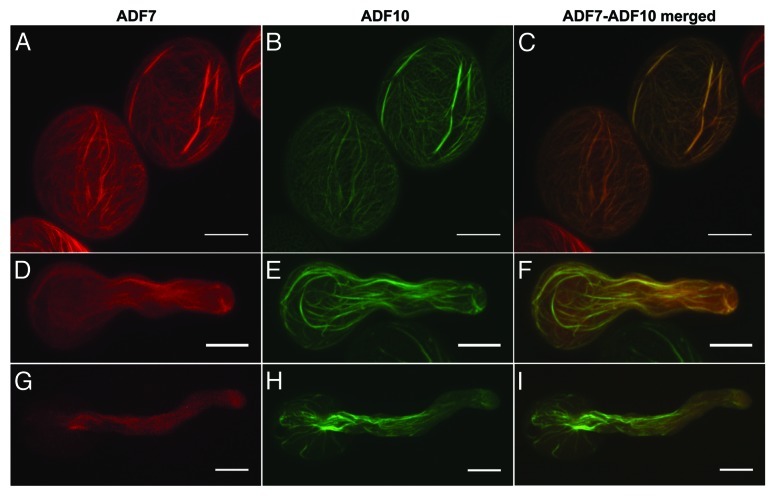

One of the actin binding proteins involved in the regulation of actin dynamics in plant cells is the actin depolymerizing factor (ADF).11 ADF binds preferentially to ADP-actin12 causing the loss of actin subunits at the pointed end of the filaments and creating elevated rates of actin treadmilling.13 In a recent paper we used the fluorescent tagging of full length protein technique14 to visualize two Arabidopsis pollen specific ADFs, ADF7 and ADF10, in developing pollen grains and pollen tubes.15 We were able to demonstrate that ADF7 and ADF10 under their native promoter are differentially expressed during the different steps of pollen development and that the proteins localize to distinct cellular regions during pollen tube growth. Here we exploited the fact that we had coupled the two proteins to different fluorescent proteins (CFP and YFP, respectively) to cross the two lines and produce Arabidopsis plants coexpressing the chimeric genes. This allowed us to investigate the subcellular localization of these proteins simultaneously to determine whether they differ in their dynamics. In pollen grains hydrated for 15 min in growth medium, ADF7 and ADF10 displayed very similar distribution patterns with high concentrations in the vicinity of the apertures and on the thicker actin cables (Fig. 1A–C). On thinner actin filament cables or individual filaments, ADF10 was dominant as shown by the predominantly green label in the merged image (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Subcellular localization of Arabidopsis ADF7 and ADF10 in hydrated pollen grains (A–C), short (D–F) and long pollen tubes (G,H and I). Micrographs (A,B,D,E,G and H) are maximum projections of Z-stacks acquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 META/LSM 5 LIVE/Axiovert 200M system confocal microscope using a two channel function. ADF7-CFP imaging was performed with a 458 nm laser and ADF10-YFP fluorescence was excited with a 488 nm argon laser. Micrographs in (C,F and I) are merged images of the corresponding ADF7 (red) and ADF10 (green) micrographs. Yellow indicates colocalization. Images are shown in false color. Scale bars = 10 µm.

In pollen grains shortly after germination, ADF7 decoration of actin cables was strongly reduced compared with the ungerminated grain (Fig. 1D–F). Also, diffuse ADF7 label seemed to indicate that a large portion of the protein was not bound to actin filaments at this stage. This contrasted with the behavior of ADF10, most or all of which was clearly associated with filamentous actin. Diffuse and therefore non-bound ADF7 was particularly abundant in the apical region of the young pollen tube, whereas ADF10 displayed rather distinct label on finer actin filaments in the same region. Both proteins also labeled thicker actin cables in this growing region of the cell.

In long pollen tubes (Fig. 1G–I), ADF7 appeared rather diffuse and barely colocalized with any filamentous structures in the pollen grain or tube. Despite its diffuse localization, a higher density of ADF7 was clearly visible in the region of the apical actin fringe. This fringe was also labeled for ADF10, which was more clearly associated with individual filaments in this structure. ADF10 was also associated with numerous thicker actin cables both in the tube and the grain. The diffuse label for ADF7 at the advanced stage of pollen tube growth could be explained by either of two processes. Either the protein is not involved in pollen tube growth at this stage and the diffuse label indicates a slow recycling of the remaining protein, or, on the contrary, ADF7 acts very efficiently. If ADF7 operated immediately upon contact with the pointed end of an actin filament and detached together with an actin monomer, the resulting label would be expected to be primarily diffuse. This second alternative is supported by the fact that label, albeit diffuse, was indeed still present, and that it was more intense in the subapical region of the tube where actin dynamics is known to be very high. ADF7 might thus be involved in the rapid disassembly and reassembly of actin filaments forming the pollen tube fringe, possibly by continuously shuttling actin monomers toward the growing front of the fringe. On the other hand, the more stable association of ADF10 to thicker actin cables seems to suggest that this member of the ADF family identifies more stable actin configurations located in the older region of the tube for recycling.

The distinct subcellular localizations of ADF7 and ADF10 during pollen maturation and pollen tube growth suggest that these two members of the ADF family have different roles in the cellular growth process, but more research is warranted to better define these functions. Recent data on Arabidopsis ADF9 revealed that this member of the family may have an actin-stabilizing activity in vitro,16 thus demonstrating that this protein family may hide surprises. The availability of stable transformants that combine the chimeric genes for ADF7 and ADF10 will open the way for a wide panoply of experiments to be conducted both in vivo and in vitro. Future experimentation will enable us to investigate the physiological and biochemical functions of these two proteins, and thus to contribute to our understanding of the role of the ADF protein family in plant development.

Acknowledgments

Research in the Geitmann lab is supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies (FQRNT).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/20436

References

- 1.Bou Daher F, Geitmann A. Actin is involved in pollen tube tropism through redefining the spatial targeting of secretory vesicles. Traffic. 2011;12:1537–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bove J, Vaillancourt B, Kroeger J, Hepler PK, Wiseman PW, Geitmann A. Magnitude and direction of vesicle dynamics in growing pollen tubes using spatiotemporal image correlation spectroscopy and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:1646–58. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.120212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chebli Y, Geitmann A. Mechanical principles governing pollen tube growth. Funct Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2007;1:232–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fayant P, Girlanda O, Chebli Y, Aubin CE, Villemure I, Geitmann A. Finite element model of polar growth in pollen tubes. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2579–93. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geitmann A, Emons AMC. The cytoskeleton in plant and fungal cell tip growth. J Microsc. 2000;198:218–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ. Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2349–63. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gossot O, Geitmann A. Pollen tube growth: coping with mechanical obstacles involves the cytoskeleton. Planta. 2007;226:405–16. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidali L, McKenna ST, Hepler PK. Actin polymerization is essential for pollen tube growth. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2534–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung AY, Wu H-M. Overexpression of an Arabidopsis formin stimulates supernumerary actin cable formation from pollen tube cell membrane. Plant Cell. 2004;16:257–69. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung AY, Niroomand S, Zou Y, Wu H-M. A transmembrane formin nucleates subapical actin assembly and controls tip-focused growth in pollen tubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16390–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008527107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlier M-F, Laurent V, Santolini J, Melki R, Didry D, Xia G-X, et al. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maciver SK, Hussey PJ. The ADF/cofilin family: actin-remodeling proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:reviews3007. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamburg JR, McGough A, Ono S. Putting a new twist on actin: ADF/cofilins modulate actin dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:364–70. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian G-W, Mohanty A, Chary SN, Li S, Paap B, Drakakaki G, et al. High-throughput fluorescent tagging of full-length Arabidopsis gene products in planta. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:25–38. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bou Daher F, van Oostende C, Geitmann A. Spatial and temporal expression of actin depolymerizing factors ADF7 and ADF10 during male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:1177–92. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tholl S, Moreau F, Hoffmann C, Arumugam K, Dieterle M, Moes D, et al. Arabidopsis actin-depolymerizing factors (ADFs) 1 and 9 display antagonist activities. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1821–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]