Abstract

Salvia miltiorrhiza is an important medicinal plant with great economic and medicinal value. The complete chloroplast (cp) genome sequence of Salvia miltiorrhiza, the first sequenced member of the Lamiaceae family, is reported here. The genome is 151,328 bp in length and exhibits a typical quadripartite structure of the large (LSC, 82,695 bp) and small (SSC, 17,555 bp) single-copy regions, separated by a pair of inverted repeats (IRs, 25,539 bp). It contains 114 unique genes, including 80 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNAs and four rRNAs. The genome structure, gene order, GC content and codon usage are similar to the typical angiosperm cp genomes. Four forward, three inverted and seven tandem repeats were detected in the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome. Simple sequence repeat (SSR) analysis among the 30 asterid cp genomes revealed that most SSRs are AT-rich, which contribute to the overall AT richness of these cp genomes. Additionally, fewer SSRs are distributed in the protein-coding sequences compared to the non-coding regions, indicating an uneven distribution of SSRs within the cp genomes. Entire cp genome comparison of Salvia miltiorrhiza and three other Lamiales cp genomes showed a high degree of sequence similarity and a relatively high divergence of intergenic spacers. Sequence divergence analysis discovered the ten most divergent and ten most conserved genes as well as their length variation, which will be helpful for phylogenetic studies in asterids. Our analysis also supports that both regional and functional constraints affect gene sequence evolution. Further, phylogenetic analysis demonstrated a sister relationship between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Sesamum indicum. The complete cp genome sequence of Salvia miltiorrhiza reported in this paper will facilitate population, phylogenetic and cp genetic engineering studies of this medicinal plant.

Introduction

Chloroplasts, one of the main distinguishing characteristics of plant cells, are now generally accepted to have originated from cyanobacteria through endosymbiosis [1], [2]. In addition to their central function of photosynthesis, chloroplasts also participate in the biosynthesis of starch, fatty acids, pigments and amino acids [3]. Since the first cp genome sequence of Marchantia polymorpha [4] was reported in 1986, over 285 complete cp genome sequences have been deposited in the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/ORGANELLES/organelles.html). A typical circular cp genome has a conserved quadripartite structure, including a pair of inverted repeats (IRs), separated by a large single-copy region (LSC) and a small single-copy region (SSC). In angiosperms, the majority of the cp genomes range from 120 to 160 kb in length [5] and exhibit highly conserved gene order and contents [2], [6]. However, large-scale genome rearrangement and gene loss have been identified in several angiosperm lineages [7], [8]. Cp genome sequences are useful for phylogenetic [9], DNA barcoding [10], population [11] and transplastomic [12] studies.

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen in Chinese) is a deciduous perennial flowering plant in the family Lamiaceae and the order Lamiales. It is a significant traditional Chinese medicinal herb widely cultivated in China with great economic and medicinal value [13]. The dried roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza, commonly known as ‘Chinese sage’ or ‘red sage’ in western countries, are widely used in the treatment of several diseases, including but not limited to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and hyperlipidemia diseases [14]–[17]. More than 70 compounds have been isolated and structurally identified from the root of Salvia miltiorrhiza to date [18], [19]. These compounds can be divided into two major groups: the hydrophilic phenolic acids, including rosmarinic, lithospermic and salvianolic acids; and the lipophilic components, including diterpenoids and tanshinones [14], [19]. Modern pharmacological research has demonstrated that compounds in both categories have multiple important and desirable therapeutic actions, including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antivirus, anti-atherosclerotic and antioxidant activities [14], [15], [20]. In addition to the significant medicinal value described above, Salvia miltiorrhiza is exemplary for its relatively small genome size (∼600 Mb), short life cycle and genetic transformability [21]–[24]. These characteristics make Salvia miltiorrhiza an exemplary starting point to investigate the mechanism of medicinal plant secondary metabolism.

To date, few data are available regarding the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome. Here, as a part of the genome sequencing project of Salvia miltiorrhiza, we report its complete cp genome sequence, determined using both pyrosequencing and SOLiD technologies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first complete cp genome sequence in Lamiaceae, the sixth-largest family of angiosperms [25]. Comparative sequence analysis was conducted among published asterid cp genomes. These data may contribute to a better understanding of evolution within the asterid clade.

Materials and Methods

DNA Sequencing, Genome Assembly and Validation

Fresh leaves were collected from the Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (line 993) grown in a field nursery at the medicinal plant garden of the Institute of Medicinal Plant Development. Total DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA) and used for constructing shotgun libraries according to the manufacturer’s manual for the 454 GS FLX Titanium [26]. A total of 20 GS FLX runs were carried out for the project. In addition, three 2×50 mate-paired libraries with insert sizes of 1, 3 and 5 kb were constructed following the SOLiD Library Preparation Guide and sequenced on a SOLiD 3 plus platform for 1/2, 3/4 and 1/2 runs, respectively.

After quality control, the trimmed and cleaned reads were used to assemble the cp genome. First, the 454 reads were used to generate a raw cp genome assembly. Then, the SOLiD mate-paired reads were mapped to the raw assembly using BioScope (version 1.3, see BioScope Software for Scientists Guide) to correct the erroneous homopolymers. We thus acquired a high quality complete cp genome. To verify the assembly, four junction regions between IRs and LSC/SSC were confirmed by PCR amplifications and Sanger sequencing using the primers listed in Table S1.

Genome Annotation, Codon Usage and Intra-specific SNPs

The cp genome was annotated using the program DOGMA [27] coupled with manual corrections for start and stop codons. The tRNA genes were identified using DOGMA and tRNAscan-SE [28]. The nomenclature of cp genes was referred to the ChloroplastDB [29]. The circular cp genome map was drawn using the OGDRAW program [30]. Codon usage and GC content were analyzed using MEGA5 [31]. Intra-specific SNPs were called by mapping the SOLiD mate-paired reads to the cp genome assembly using BioScope.

Genome Comparison and Repeat Content

MUMmer [32] was used to perform pairwise cp genomic alignment. mVISTA [33] was used to compare the cp genome of Salvia miltiorrhiza with three other cp genomes using the annotation of Salvia miltiorrhiza as reference. REPuter [34] was used to visualize both forward and inverted repeats. The minimal repeat size was set to 30 bp and the identity of repeats was no less than 90% (hamming distance equal to 3). Tandem repeats were analyzed using Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) v4.04 [35] with parameter settings as described by Nie et al [36]. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected using MISA (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/), with thresholds of eight repeat units for mononucleotide SSRs, four repeat units for di- and trinucleotide SSRs and three repeat units for tetra-, penta- and hexanucleotide SSRs. All of the repeats found were manually verified, and the redundant results were removed.

Sequence Divergence and Phylogenetic Analysis

The 29 complete cp sequences representing the asterid lineage of angiosperms were downloaded from NCBI Organelle Genome Resources database (Table S2). The 80 protein-coding gene sequences were aligned using the Clustal algorithm [37]. Pairwise sequence divergences were calculated using Kimura’s two-parameter (K2P) model [38].

For the phylogenetic analysis, a set of 71 protein-coding genes commonly present in the 30 analyzed genomes was used. Maximum parsimony (MP) analysis was performed with PAUP*4.0b10 [39] using heuristic search, random addition with 1,000 replicates and tree bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping with the Multrees option in effect. Bootstrap analysis was performed with 1,000 replicates with TBR branch swapping. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was also performed using PAUP with the GTR+I+G nucleotide substitution model. This adopted best-fit model was determined by Modeltest 3.7 [40]. Spinacia oleracea and Arabidopsis thaliana were set as outgroups.

Results

Genome Assembly and Validation

The annotated cp genome sequence of Arabidopsis thaliana was taken from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). The Arabidopsis genes encoding psbA and ndhI were located in the LSC and SSC regions of the cp genome, respectively. Homologs of these two genes were identified in the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome by searching 454 reads using the BLASTn algorithm [41]. Both genes then served as seed sequences for Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome assembly.

The draft sequence of the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome was constructed by extending the two seed sequences on both the 5′ and 3′ ends in a step-by-step manner until they overlapped at both the IRa and IRb regions. Detailed procedures for each extension step are described as follows. All of the 454 reads showing homology to the seed sequence were identified in a similarity search, using the BLASTn algorithm with a threshold of ≥95% homology. Of these reads, the one with best alignment to the 5′ or 3′ end of the seed sequence was selected and used to extend the seed sequence.

Cp genome reads were screened out by mapping all 454 reads to the draft cp genome sequence, using the BLASTn algorithm with a threshold of ≥95% homology. A total of 1,767,159 reads (7.4% of total reads) were obtained, with an average length of 384 bp, thus yielding 4,492× coverage of the cp genome. The consensus sequence for a specific position was generated by assembling reads mapped to the position using CAP3 [42] and was then used to construct the complete sequence of the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome.

Erroneous homopolymers, which are intrinsic to pyrosequencing [43], were manually corrected by mapping all SOLiD reads to the cp genome assembly using BioScope. To validate the assembly, four junctions between IRs and LSC/SSC were confirmed by PCR amplifications and Sanger sequencing. We compared the Sanger results with the assembled genome, and no mismatch or indel was observed, which demonstrated the accuracy of our assembly. The final cp genome of Salvia miltiorrhiza was then submitted to GenBank (accession number: JX312195).

Genome Features

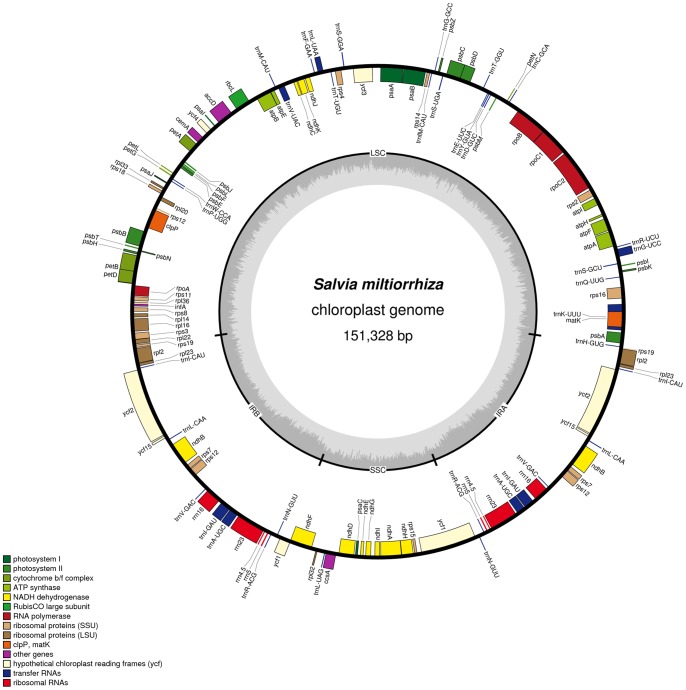

The complete cp genome of Salvia miltiorrhiza is 151,328 bp in length, which is in range with those from other angiosperms [5], and exhibits a typical quadripartite structure, consisting of a pair of IRs (25,539 bp) separated by the LSC (82,695 bp) and SSC (17,555 bp) regions (Table 1, Figure 1). The overall GC content of the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome is 38.0%, which is similar to the other reported asterid cp genomes [44]–[48]. The GC content of the IR regions (43.1%) is higher than that of the LSC and SSC regions (36.2% and 32.0%, respectively). The high GC content of the IR regions is caused by the high GC content of the four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (55.2%) present in this region.

Table 1. Base composition in the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

| T(U) (%) | C (%) | A (%) | G (%) | Length (bp) | ||

| LSC | 32.6 | 18.5 | 31.2 | 17.7 | 82,695 | |

| SSC | 33.8 | 16.7 | 34.2 | 15.3 | 17,555 | |

| IRa | 28.5 | 22.4 | 28.4 | 20.7 | 25,539 | |

| IRb | 28.4 | 20.7 | 28.5 | 22.4 | 25,539 | |

| Total | 31.3 | 19.3 | 30.6 | 18.7 | 151,328 | |

| CDS | 31.4 | 17.8 | 30.5 | 20.3 | 79,080 | |

| 1st position | 23.7 | 19.0 | 30.5 | 26.8 | 26,360 | |

| 2nd position | 32.6 | 20.4 | 29.2 | 17.8 | 26,360 | |

| 3rd position | 37.8 | 14.0 | 31.8 | 16.3 | 26,360 |

CDS: protein-coding regions.

Figure 1. Gene map of the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

Genes drawn inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outside are counterclockwise. Genes belonging to different functional groups are color-coded. The darker gray in the inner circle corresponds to GC content, while the lighter gray corresponds to AT content.

The Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome encodes 131 predicted functional genes, of which 114 are unique, including 80 protein-coding genes, 30 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes and four rRNA genes (Figure 1, Table S3). Six protein-coding, seven tRNA and all four rRNA genes are duplicated in the IR regions. The LSC region contains 61 protein-coding and 22 tRNA genes, whereas the SSC region contains 12 protein-coding and one tRNA genes. Similar to the Nicotiana tabacum [48] and Panax ginseng [47] cp genomes, the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome has 18 intron-containing genes, 15 (nine protein-coding and six tRNA genes) of which contain one intron and three (clpP, rps12 and ycf3) of which contain two introns (Table 2). The rps12 gene is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′ end in the IR regions. The trnK-UUU has the largest intron (2,522 bp) containing the matK gene.

Table 2. The genes with introns in the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome and the length of the exons and introns.

| Gene | Location | Exon I (bp) | Intron I (bp) | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon III (bp) |

| atpF | LSC | 144 | 699 | 411 | ||

| clpP | LSC | 71 | 692 | 292 | 628 | 228 |

| ndhA | SSC | 553 | 985 | 539 | ||

| ndhB | IR | 777 | 675 | 756 | ||

| petB | LSC | 6 | 702 | 642 | ||

| petD | LSC | 8 | 720 | 475 | ||

| rpl16 | LSC | 9 | 873 | 399 | ||

| rpl2 | IR | 391 | 658 | 434 | ||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 456 | 759 | 1620 | ||

| rps12* | LSC | 114 | - | 232 | 526 | 26 |

| rps16 | LSC | 42 | 874 | 195 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 795 | 35 | ||

| trnG-UCC | LSC | 23 | 682 | 48 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 37 | 940 | 35 | ||

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 37 | 2522 | 35 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 37 | 453 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 36 | 576 | 37 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 129 | 696 | 228 | 726 | 153 |

The rps12 is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′ end in the IR regions.

52.3%, 1.8% and 6.0% of the genome sequence encode proteins, tRNAs and rRNAs, respectively. The remaining regions are non-coding sequences, including introns, intergenic spacers and pseudogenes. The 30 unique tRNA genes include all of the 20 amino acids required for protein biosynthesis. Moreover, the 86 protein-coding genes comprise 79,080 bp coding for 26,360 codons. Based on the sequences of protein-coding genes and tRNA genes, the frequency of codon usage was deduced for the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome and summarized in Table 3. Among these codons, 2,806 (10.6%) encode leucine, and 292 (1.1%) encode cysteine, which are the most and least prevalent amino acids, respectively. Within protein-coding regions (CDS), the percentage of AT content for the first, second and third codon positions are 54.2%, 61.8% and 69.6%, respectively (Table 1). The bias towards a higher AT representation at the third codon position was also observed in other land plant cp genomes [5], [36], [44], [49], [50].

Table 3. The codon–anticodon recognition pattern and codon usage for the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

| Amino acid | Codon | No. | RSCU | tRNA | Amino acid | Codon | No. | RSCU | tRNA |

| Phe | UUU | 999 | 1.33 | Tyr | UAU | 771 | 1.63 | ||

| Phe | UUC | 499 | 0.67 | trnF-GAA | Tyr | UAC | 175 | 0.37 | trnY-GUA |

| Leu | UUA | 860 | 1.84 | trnL-UAA | Stop | UAA | 46 | 1.6 | |

| Leu | UUG | 569 | 1.22 | trnL-CAA | Stop | UAG | 22 | 0.77 | |

| Leu | CUU | 609 | 1.3 | His | CAU | 479 | 1.53 | ||

| Leu | CUC | 180 | 0.38 | His | CAC | 146 | 0.47 | trnH-GUG | |

| Leu | CUA | 394 | 0.84 | trnL-UAG | Gln | CAA | 723 | 1.54 | trnQ-UUG |

| Leu | CUG | 194 | 0.41 | Gln | CAG | 217 | 0.46 | ||

| Ile | AUU | 1096 | 1.48 | Asn | AAU | 967 | 1.54 | ||

| Ile | AUC | 461 | 0.62 | trnI-GAU | Asn | AAC | 289 | 0.46 | trnN-GUU |

| Ile | AUA | 667 | 0.9 | trnI-CAU | Lys | AAA | 1062 | 1.48 | trnK-UUU |

| Met | AUG | 629 | 1 | trn(f)M-CAU | Lys | AAG | 370 | 0.52 | |

| Val | GUU | 526 | 1.46 | Asp | GAU | 867 | 1.6 | ||

| Val | GUC | 178 | 0.5 | trnV-GAC | Asp | GAC | 216 | 0.4 | trnD-GUC |

| Val | GUA | 542 | 1.51 | trnV-UAC | Glu | GAA | 1016 | 1.5 | trnE-UUC |

| Val | GUG | 191 | 0.53 | Glu | GAG | 343 | 0.5 | ||

| Ser | UCU | 584 | 1.7 | Cys | UGU | 222 | 1.52 | ||

| Ser | UCC | 344 | 1 | trnS-GGA | Cys | UGC | 70 | 0.48 | trnC-GCA |

| Ser | UCA | 398 | 1.16 | trnS-UGA | Stop | UGA | 18 | 0.63 | |

| Ser | UCG | 200 | 0.58 | Trp | UGG | 470 | 1 | trnW-CCA | |

| Pro | CCU | 405 | 1.44 | Arg | CGU | 338 | 1.28 | trnR-ACG | |

| Pro | CCC | 234 | 0.83 | Arg | CGC | 121 | 0.46 | ||

| Pro | CCA | 324 | 1.15 | trnP-UGG | Arg | CGA | 353 | 1.33 | |

| Pro | CCG | 161 | 0.57 | Arg | CGG | 131 | 0.49 | ||

| Thr | ACU | 539 | 1.63 | Arg | AGA | 488 | 1.84 | trnR-UCU | |

| Thr | ACC | 247 | 0.75 | trnT-GGU | Arg | AGG | 159 | 0.6 | |

| Thr | ACA | 388 | 1.17 | trnT-UGU | Ser | AGU | 420 | 1.22 | |

| Thr | ACG | 150 | 0.45 | Ser | AGC | 115 | 0.33 | trnS-GCU | |

| Ala | GCU | 603 | 1.73 | Gly | GGU | 539 | 1.21 | ||

| Ala | GCC | 234 | 0.67 | Gly | GGC | 191 | 0.43 | trnG-GCC | |

| Ala | GCA | 393 | 1.13 | trnA-UGC | Gly | GGA | 720 | 1.62 | trnG-UCC |

| Ala | GCG | 167 | 0.48 | Gly | GGG | 331 | 0.74 |

RSCU: Relative Synonymous Codon Usage.

A given plant cell often contains multiple copies of cp genomes [51] that can be regarded as a population with genetic heterogeneity [5]. We mapped all SOLiD reads to the assembled genome to detect the possible polymorphic sites. However, no SNPs were recovered. A similar result was also observed in another cp genome, i.e., Boea hygrometrica (Gesneriaceae), which is also a member of the order Lamiales [46].

Repeat Analysis

For repeat structure analysis, four forward, three inverted and seven tandem repeats were detected in the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome (Table 4). Most of these repeats exhibit lengths between 30 and 41 bp, while the CDS of the ycf2 gene possesses the two longest tandem repeats at 63 and 108 bp. Three pairs of repeats associated with tRNA genes (Nos. 1, 5 and 6) and four tandem repeats (Nos. 8–11) in the intergenic spacers are distributed in the LSC region. A comparison of repeats between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Sesamum indicum shows that three repeats (Nos. 4, 5 and 7) are at the same location in the two cp genomes.

Table 4. Repeated sequences in the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

| Repeat number | Size (bp) | Type | Location | Repeat Unit | Region |

| 1 | 30 | F | trnG-UCC, trnG-GCC | AACGATGCGGGTTCGATTCCCGCTACCCGC | LSC |

| 2 | 32 | F | psaB (CDS), psaA (CDS) | AGCTAAATGATGATGAGCCATATCAGTCAACC | LSC |

| 3 | 39 | F | ycf3 (intron), ndhA (intron) | CCAGAACCGTACGTGAGATTTTCACCTCATACGGCTCCT | LSC, SSC |

| 4 | 41 | F | IGS (rps12, trnV-GAC), ndhA (intron) | CTACAGAACCGTACATGAGATTTTCACCTCATACGGCTCCT | IRb, SSC |

| 5 | 30 | I | trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA | AACGGAAAGAGAGGGATTCGAACCCTCGGT | LSC |

| 6 | 30 | I | trnS-UGA, trnS-GGA | AGGGGAGAGAGAGGGATTCGAACCCTCGAT | LSC |

| 7 | 41 | I | ndhA (intron), IGS (trnV-GAC, rps12) | TTACAGAACCGTACATGAGATTTTCACCTCATACGGCTCCT | SSC, IRa |

| 8 | 40 | T | IGS (rps16, trnQ-UUG) | ACTATATAGAATATATATAA (×2) | LSC |

| 9 | 32 | T | IGS (accD, psaI) | TTAGCTTATCCGAATC (×2) | LSC |

| 10 | 33 | T | IGS (accD, psaI) | AATTAATAATAACTAC (×2) | LSC |

| 11 | 34 | T | IGS (petA, psbJ) | CGCACTCTTAGTCATAA (×2) | LSC |

| 12 | 63 | T | ycf2 (CDS) | TTTTTGTCCAAGTCACTTCTT (×3) | IRb,a |

| 13 | 108 | T | ycf2 (CDS) | TATTGATGAGAGTGACGA (×6) | IRb,a |

| 14 | 39 | T | ndhF (CDS) | AATAAAAACCTAAAATCCCT (×2) | SSC |

F: Forward; I: Inverted; T: Tandem; IGS: Intergenic spacer; CDS: protein-coding regions. The underline represents the shared repeats with Sesamum indicum.

SSR Analysis

SSRs, also known as microsatellites, are tandemly repeated DNA sequences that are generally 1–6 bp in length per unit and are distributed throughout the genome. SSRs have been accepted as one of the major sources of molecular markers due to their high polymorphism level within the same species and have been widely employed in population genetics and phylogenetic investigations [11], [52]–[54]. We detected perfect SSRs longer than 8 bp in Salvia miltiorrhiza together with 29 other asterid cp genomes. This threshold was set because SSRs of 8 bp or longer are prone to slip-strand mispairing, which is thought to be the primary mutational mechanism causing their high level of polymorphism [55]–[57]. In our analysis, the total number of SSRs ranged from 145 in Panax ginseng to 217 in Anthriscus cerefolium (Table 5), and a repertoire of 166 SSRs were detected in the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome. The majority of SSRs in all species are mononucleotides, varying in quantity from 92 in Panax ginseng to 155 in Olea europaea. Dinucleotides are the second most prevalent, ranging in quantity from 33 in Helianthus annuus to 62 in Anthriscus cerefolium. Generally, the number of tetranucleotides is slightly higher than that of trinucleotides, and only rarely are pentanucleotides or hexanucleotides observed in the asterid cp genomes. The majority of tri- to hexanucleotides are AT-rich in all species. An average of 68% (72% in Salvia miltiorrhiza) of all SSRs are A/T mononucleotides in these cp genomes, slightly lower than the 76% found in a previous study of 14 monocot cp genomes [56]. Our finding agrees with the contention that cp SSRs are generally composed of short polyadenine (polyA) or polythymine (polyT) repeats and rarely contain tandem guanine (G) or cytosine (C) repeats [58]. Thus, these SSRs contribute to the AT richness of the asterid cp genomes. We also detected SSRs in the CDS of each cp genome. The CDS accounts for approximately 50% of the total length in most cp genomes, whereas the SSR proportion ranges from 23% to 41%. This result indicates that SSRs are less abundant in CDS than in non-coding regions and that they are unevenly distributed within the cp genomes. In total, 53 SSRs were identified in the CDS of 23 genes in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Among them, 10 genes were found to harbor at least two SSRs, including ndhD, matK, rpoC2, ycf1 and ycf2, among others.

Table 5. Distribution of SSRs present in the 30 asterid chloroplast genomes.

| Taxon | Genome Size (bp) | AT (%) | SSR type | CDS | ||||||||

| Mono | Di | Tri | Tetra | Penta | Hexa | Total | %a | No.b | %c | |||

| Ageratina adenophora | 150,698 | 63 | 115 | 35 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 162 | 49 | 50 | 31 |

| Anthriscus cerefolium | 154,719 | 63 | 141 | 62 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 217 | 50 | 68 | 31 |

| Atropa belladonna | 156,687 | 62 | 117 | 46 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 174 | 51 | 50 | 29 |

| Boea hygrometrica | 153,493 | 62 | 98 | 40 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 149 | 52 | 46 | 31 |

| Coffea arabica | 155,189 | 63 | 115 | 46 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 168 | 51 | 57 | 34 |

| Datura stramonium | 155,871 | 62 | 109 | 40 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 52 | 53 | 33 |

| Daucus carota | 155,911 | 62 | 133 | 56 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 205 | 50 | 69 | 34 |

| Eleutherococcus senticosus | 156,768 | 62 | 109 | 47 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 165 | 50 | 56 | 34 |

| Guizotia abyssinica | 151,762 | 62 | 119 | 42 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 172 | 52 | 71 | 41 |

| Helianthus annuus | 151,104 | 62 | 119 | 33 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 51 | 63 | 39 |

| Ipomoea purpurea | 162,046 | 63 | 146 | 38 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 204 | 53 | 67 | 33 |

| Jacobaea vulgaris | 150,689 | 63 | 124 | 51 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 191 | 51 | 55 | 29 |

| Jasminum nudiflorum | 165,121 | 62 | 149 | 42 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 214 | 50 | 81 | 38 |

| Lactuca sativa | 152,765 | 62 | 118 | 49 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 172 | 48 | 43 | 25 |

| Nicotiana sylvestris | 155,941 | 62 | 118 | 41 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 174 | 54 | 62 | 36 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | 155,943 | 62 | 118 | 41 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 174 | 54 | 62 | 36 |

| Nicotiana tomentosiformis | 155,745 | 62 | 122 | 43 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 178 | 54 | 58 | 33 |

| Nicotiana undulata | 155,863 | 62 | 119 | 41 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 174 | 56 | 62 | 36 |

| Olea europaea | 155,888 | 62 | 155 | 35 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 196 | 51 | 50 | 26 |

| Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata | 155,862 | 62 | 152 | 36 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 193 | 51 | 46 | 24 |

| Olea europaea subsp. europaea | 155,875 | 62 | 153 | 35 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 193 | 51 | 46 | 24 |

| Olea europaea subsp. maroccana | 155,896 | 62 | 153 | 36 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 194 | 51 | 46 | 24 |

| Olea woodiana subsp. woodiana | 155,942 | 62 | 153 | 36 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 195 | 51 | 45 | 23 |

| Panax ginseng | 156,318 | 62 | 92 | 39 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 145 | 50 | 54 | 37 |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | 151,328 | 62 | 122 | 35 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 166 | 52 | 53 | 32 |

| Sesamum indicum | 153,324 | 62 | 137 | 38 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 186 | 51 | 54 | 29 |

| Solanum bulbocastanum | 155,371 | 62 | 106 | 37 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 155 | 51 | 48 | 31 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 155,461 | 62 | 114 | 33 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 156 | 51 | 46 | 29 |

| Solanum tuberosum | 155,296 | 62 | 103 | 36 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 150 | 51 | 46 | 31 |

| Trachelium caeruleum | 162,321 | 62 | 96 | 47 | 5 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 166 | 43 | 44 | 27 |

CDS: protein-coding regions.

Percentage were calculated according to the total length of the CDS divided by the genome size.

Total number of SSRs identified in the CDS.

Percentage were calculated according to the total number of SSRs in the CDS divided by the total number of SSRs in the genome.

Comparison with other cp Genomes in the Lamiales Order

Nine complete cp genome sequences of the Lamiales order are currently available, representing four families and five genera. Three sequences representing Gesneriaceae (Boea hygrometrica), Oleaceae (Olea europaea) and Pedaliaceae (Sesamum indicum) were selected for comparison with Salvia miltiorrhiza. Epifagus virginiana (Orobanchaceae) was not considered because most cp genes are lost in this non-green parasitic flowering plant [7]. Jasminum nudiflorum (Oleaceae) was also excluded due to its genome rearrangements [8].

The genome size of Salvia miltiorrhiza is the smallest of the Lamiales cp genomes, with the exception of Epifagus virginiana. It is approximately 2.2 kb, 4.6 kb and 2.0 kb smaller than that of Boea hygrometrica, Olea europaea and Sesamum indicum, respectively. This variation in sequence length is mainly attributed to the difference in the length of the LSC region (Table S4).

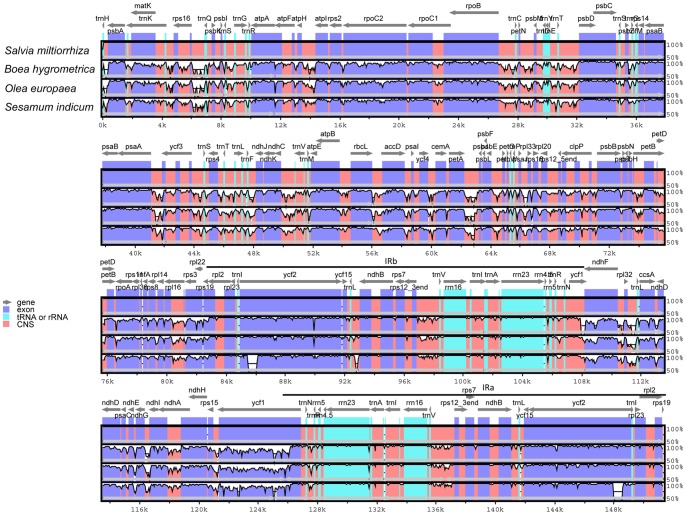

Pairwise cp genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and the three cp genomes recovered a high degree of synteny (Figure S1, S2, S3). Since the cp genome of tobacco is often regarded to be unarranged [48], we compared the four cp genomes with it and observed an approximately identical gene order and organization among them. The overall sequence identity of the four Lamiales cp genomes was plotted using mVISTA using the annotation of Salvia miltiorrhiza as reference (Figure 2). The comparison shows that the two IR regions are less divergent than the LSC and SSC regions. Additionally, non-coding regions exhibit a higher divergence than coding regions, and the most divergent regions localize in the intergenic spacers among the four cp genomes. In our alignment, these highly divergent regions include ndhD-ccsA, ndhI-ndhG, psbI-trnS and trnH-psbA, among others. Similar results were also observed in the non-coding region comparison of six Asteraceae cp genomes [36]. Cp non-coding regions have been successfully applied in phylogenetic analysis of Lamiales [59], [60] and in the DNA barcoding research presented in a growing number of studies [61], [62]. Variation between the coding sequences of Salvia miltiorrhiza and Boea hygrometrica, Olea europaea or Sesamum indicum was also analyzed by comparing each individual gene as well as the overall sequences (Table S5) [63]. The four rRNA genes are the most conserved, while the most divergent coding regions are rpl22, ycf1, ndhF, ccsA, rps15 and matK.

Figure 2. Comparison of four chloroplast genome using mVISTA program.

Grey arrows and thick black lines above the alignment indicate genes with their orientation and the position of the IRs, respectively. A cut-off of 70% identity was used for the plots, and the Y-scale represents the percent identity between 50–100%. Genome regions are color-coded as protein-coding (exon), rRNA, tRNA and conserved noncoding sequences (CNS).

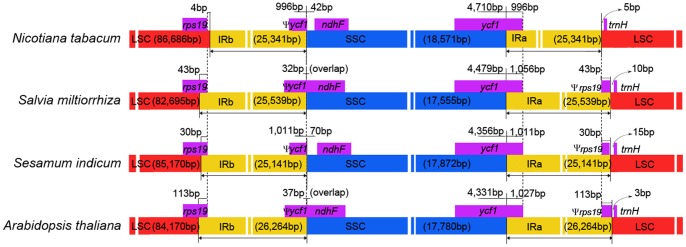

IR Contraction and Expansion

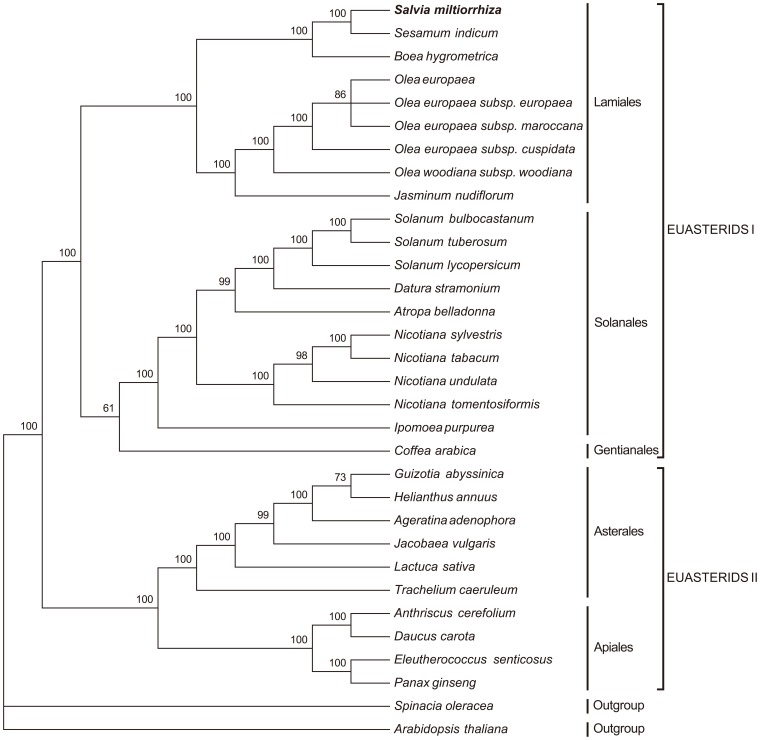

Although IRs are the most conserved regions in the cp genomes, the contraction and expansion at the borders of the IR regions are common evolutionary events and represent the main reasons for size variation of cp genomes [5], [57], [64], [65]. The IR-LSC and IR-SSC borders of the cp genomes of Arabidopsis thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum, Sesamum indicum, Salvia miltiorrhiza were compared, and those data are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Comparison of the borders of LSC, SSC and IR regions among four chloroplast genomes.

The IRb/SSC border extended into the ycf1 genes to create various lengths of ycf1 pseudogenes among four chloroplast genomes. The ycf1 pseudogene and the ndhF gene overlapped in both the Salvia miltiorrhiza and Arabidopsis thaliana cp genomes by 32 bp and 37 bp, respectively. Various lengths of rps19 pseudogenes were created at the IRa/LSC borders of Salvia miltiorrhiza, Sesamum indicum and Arabidopsis thaliana. This figure is not to scale.

The IRb/SSC border extended into the ycf1 genes to create long ycf1 pseudogenes in all of the species compared. The length of ycf1 pseudogene was 996 bp in Nicotiana tabacum, 1,011 bp in Sesamum indicum, 1,056 bp in Salvia miltiorrhiza and 1,027 bp in Arabidopsis thaliana. In addition, the ycf1 pseudogene and the ndhF gene overlapped in both the Salvia miltiorrhiza and Arabidopsis thaliana cp genomes by 32 bp and 37 bp, respectively. The IRa/SSC border was located in the CDS of ycf1 gene and expanded the same length into the 5′ portion of ycf1 gene as IRb expanded in the four cp genomes. Rps19 pseudogenes of various lengths were also found at the IRa/LSC borders. In Salvia miltiorrhiza, a short rps19 pseudogene of 43 bp was created at the IRa/LSC border. The same pseudogene was 30 bp and 113 bp in Sesamum indicum and Arabidopsis thaliana, respectively, and was not found at the same border of Nicotiana tabacum. The trnH genes of these four species were all located in the LSC region, 3–15 bp apart from the IRa/LSC border, whereas this gene was usually located in the IR region in the monocot cp genomes [56].

Sequence Divergence of Protein-coding Genes

We compared gene contents and calculated the average pairwise sequence distance of 80 protein-coding genes among 30 asterid species. The abnormal or missing annotations of several genes in some taxa were re-annotated during the sequence analysis. The results are summarized in Table S6.

Low levels of average sequence distance among the asterid coding sequences were observed. 85% of these genes have an average sequence distance less than 0.10, and only 12 genes exhibit an average sequence distance greater than 0.10. The ten most divergent genes are ycf15, ycf1, rpl22, rpl32, matK, clpP, ndhF, ccsA, rps15 and accD. The highest average sequence distance was observed in ycf15 (0.41), followed by ycf1 (0.28). The latter is located at the LSC/IR border and shows a fast evolving trend. Previously reported comparison of each individual region revealed different sets of the most divergent genes in the different cp genomes analyzed. RpoC1 and ycf1 were identified to be the most divergent genes in six Asteraceae cp genomes [36]; ycf1, accD, clpP, rps16 and ndhA were observed to be the most divergent coding regions in Parthenium argentatum and its closely related species [63]; ycf1, matK, accD, rpl22, infA, ycf2, rps15, ccsA and rpl32 were the most divergent genes in 16 vascular plant cp genomes [47]. The most divergent genes in asterids are similar for most of the genes indicated above, but they also include ndhF and ycf15.

The ten most conserved genes are ndhB, rpl2, psbL, petG, rps7, rpl23, psbN, psbF, psbZ and psbA. Of them, the three rpl and rps genes located in IR regions show lower average sequence distances than the other rpl or rps genes located in the LSC or SSC regions. This supports the hypothesis that sequences in the IR regions diverge at a slower rate than sequences located in the LSC or SSC regions. This slower divergence may occur because the two IR regions suffer frequent intra-molecular recombination events, which provide selective constraints on both sequence homogeneity and structural stability [44]. However, some genes (e.g. ycf2 and the 3′ end of rps12) in IRs exhibit more variation than several genes in the LSC or SSC regions. Furthermore, the ycf15 gene was found to be 31 times more diverse than the nhdB gene, though both genes are located in the IRs. In addition to the effect of regional constraints on sequence evolution, functional constraints were also demonstrated to affect the divergence levels of genes in asterids. For example, the majority of the psa, psb and pet gene classes show relatively slow evolutionary divergence. Similar results were also observed in the study of Kim and Lee [47].

The gene contents are relatively conserved among the 30 asterid cp genomes, with the exception of some species. The accD gene becomes pseudogene in Jasminum nudiflorum and Trachelium caeruleum. In addition to accD, the five genes clpP, infA, ndhK, rpl23 and ycf15 exist as pseudogenes in Trachelium caeruleum. PsbI and rps19 exist as pseudogenes in Boea hygrometrica. InfA and ycf15 were lost in 10 and 17 species, respectively. In terms of length variation, 14 genes show no variation, and 20 genes show less than 10 bp variation. The majority of these length-conserved genes belong to the psa, psb and pet gene classes. In addition, large-scale sequence length variation (>1,000 bp) was observed in ycf1 and ycf2. The length variation of ycf1 is attributed to the indel mutation and IR contraction and expansion, and the length variation of ycf2 is caused by the internal indel mutation associated with short direct repeats [47], [66]. When both sequence divergence and length variation are considered, ycf1 and ycf2, together with accD, clpP, ndhF and matK, are probably good candidates for phylogenetic studies among closely related species in asterids.

Phylogenetic Analysis

To identify the phylogenetic position of Salvia miltiorrhiza within the asterid lineage, we performed multiple sequence alignments using 71 protein-coding genes commonly present in the aforementioned cp genomes. The 30 complete cp genomes represent 10 families within five orders of asterids, including Apiaceae, Araliaceae, Asteraceae, Convolvulaceae, Gesneriaceae, Lamiaceae, Oleaceae, Pedaliaceae, Rubiaceae and Solanaceae (Table S2). Two additional eudicot cp genomes, Spinacia oleracea and Arabidopsis thaliana, were set as outgroups. The sequence alignment data matrix used for phylogenetic analysis comprised 62,939 nucleotide positions, which was reduced to 54,400 characters when gaps were excluded to avoid alignment ambiguities due to length variation.

MP analysis resulted in a single tree with a length of 36,088, a consistency index of 0.6628 and a retention index of 0.7561 (Figure 4). Bootstrap analysis showed that there were 25 out of 28 nodes with bootstrap values >95%, and 22 of these had a bootstrap value of 100%. A ML tree was obtained with the -lnL of 264933.3750 using the GTR+I+G nucleotide substitution model (Figure S4). ML bootstrap values were also high, with values of >95% for 25 of the 28 nodes, and 24 nodes with 100% bootstrap support. Both MP and ML trees had similar phylogenetic topologies, which formed two major clades, euasterids I and II. The only incongruence between the MP and ML trees was the position of Coffea. In the MP tree, Coffea was placed sister to Solanales; whereas it was positioned close to Lamiales in the ML tree. Bootstrap supporting values (61% in MP and 65% in ML) for these alternative placements were weak. Both the MP and ML phylogenetic results strongly supported, with 100% bootstrap values, the position of Salvia miltiorrhiza as the sister of the closely related species Sesamum indicum in the order Lamiales.

Figure 4. The MP phylogenetic tree of the asterid clade based on 71 protein-coding genes.

The MP tree has a length of 36,088, with a consistency index of 0.6628 and a retention index of 0.7561. Numbers above each node are bootstrap support values. Spinacia oleracea and Arabidopsis thaliana were set as outgroups.

Discussion

Genome Organization

The Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome with a pair of IRs separating the LSC and SSC regions exhibits identical gene order and content to most sequenced angiosperm cp genomes, emphasizing the highly conserved nature of these land plant cp genomes [2]. Repeat analysis revealed four forward, three inverted and seven tandem repeats in the Salvia miltiorrhiza cp genome. Most of these repeats are located in the intergenic spacers and introns, but several occur in tRNAs and CDS. Short dispersed repeats are considered to be one of the major factors promoting cp genome rearrangements because they are common in highly rearranged algal and angiosperm genomes, and many rearrangement endpoints are associated with such repeats [8], 67–70. The role of short dispersed repeats in unrearranged cp genomes is still unclear [71], [72]. All of these repeats, together with the aforementioned SSRs, are informative sources for developing markers for population studies [36].

Phylogenetic Relationships

Chloroplast genomes provide rich sources of phylogenetic information, and numerous studies using cp DNA sequences have been carried out during the past two decades, greatly enhancing our understanding of the evolutionary relationships among angiosperms [9], [73], [74]. Salvia, consisting of nearly 1,000 species, is the largest genus in the Lamiaceae family and is widely distributed throughout the world [75]. Previous phylogenetic studies employing one or several genes or intergenic regions showed evidence of a polyphyletic nature of Salvia [75], [76]. Our phylogenies based on 71 protein-coding genes placed Salvia sister to Sesamum in asterids with strong support and resolution. Both trees are congruent to that in a recent study using 32 complete asterid cp genomes [44] and to the APG tree [25]. The incongruence between the MP and ML trees regarding the position of Coffea is likely due to the limited number of complete cp genomes in Gentianales. Thus, to acquire more accurate relationships in asterids, expanded taxon sampling will be required for this large and diverse clade of angiosperms.

Implications for Chloroplast Genetic Engineering

Chloroplast genetic engineering is exemplary for its unique advantages including the possibility of multi-gene engineering in a single transformation event, transgene containment due to maternal inheritance, high levels of transgene expression and lack of gene silencing [77]–[79]. Significant progress in chloroplast transformation has been made in the model species tobacco as well as in a few major crops [78], [79]. Although the trnI/trnA and accD/rbcL intergenic spacer regions have been widely used as gene introduction sites for vector construction [79], the transformation efficiency is impaired when the sequences for homologous recombination are divergent among distantly related species [71]. The availability of the complete cp genome sequence of Salvia miltiorrhiza is helpful to identify the optimal intergenic spacers for transgene integration and to develop site-specific cp transformation vectors. The genes related to its bioactive compound synthesis [21], [24] will be the primary targets for investigation in Salvia. In addition, using cp genetic engineering to introduce useful traits, such as herbicide resistance and drought tolerance, might be other applications to improve this medicinal plant.

Conclusion

We present the first complete cp genome from Lamiaceae family using both pyrosequencing and SOLiD technologies. The gene order and genome organization of Salvia miltiorrhiza cp sequence are similar to that of tobacco and three other cp genomes in the Lamiales. Further, the distribution and location of repeated sequences were determined. SSR, protein-coding gene sequence divergence and phylogenetic analysis were performed among 30 asterid cp genomes. All the data presented in this paper will facilitate the biological study of this important medicinal plant.

Supporting Information

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Boea hygrometrica .

(TIF)

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Olea europaea .

(TIF)

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Sesamum indicum .

(TIF)

The ML phylogenetic tree (−lnL = 264933.3750) of the asterid clade based on 71 protein-coding genes. The GTR+I+G nucleotide substitution model was adopted based on the Modeltest. Numbers above each node are bootstrap support values. Spinacia oleracea and Arabidopsis thaliana were set as outgroups.

(TIF)

Primers used for assembly validation.

(DOC)

The list of accession numbers of the chloroplast genome sequences used in this study.

(DOC)

Genes present in the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

(DOC)

Size comparison of Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genomic regions with three other Lamiales chloroplast genomes.

(DOC)

Comparison of homologues between the Salvia miltiorrhiza and Boea hygrometrica ( Bh ), Olea europaea ( Oe ) or Sesamum indicum ( Si ) chloroplast genomes using the percent identity of protein-coding sequences.

(DOC)

Average pairwise sequence distance of protein-coding genes among the 30 asterid chloroplast genomes.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank the High Performance Computing (HPC) Platform of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) for the support on bioinformatics.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Key National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81130069), the National Key Technology R&D Program (Grant no. 2012BAI29B01) and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team of the University of Ministry of Education of China (Grant no. IRT1150). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ (2004) Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles. Science 304: 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D (2011) The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol 76: 273–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neuhaus HE, Emes MJ (2000) Nonphotosynthetic Metabolism in Plastids. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 51: 111–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umesono K, Inokuchi H, Ohyama K, Ozeki H (1984) Nucleotide sequence of Marchantia polymorpha chloroplast DNA: a region possibly encoding three tRNAs and three proteins including a homologue of E. coli ribosomal protein S14. Nucleic Acids Res 12: 9551–9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang M, Zhang X, Liu G, Yin Y, Chen K, et al. (2010) The complete chloroplast genome sequence of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). PLoS One 5: e12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jansen RK, Raubeson LA, Boore JL, dePamphilis CW, Chumley TW, et al. (2005) Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Methods Enzymol 395: 348–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolfe KH, Morden CW, Ems SC, Palmer JD (1992) Rapid evolution of the plastid translational apparatus in a nonphotosynthetic plant: loss or accelerated sequence evolution of tRNA and ribosomal protein genes. J Mol Evol 35: 304–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee HL, Jansen RK, Chumley TW, Kim KJ (2007) Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1161–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, Depamphilis CW, et al. (2007) Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 19369–19374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hollingsworth PM, Graham SW, Little DP (2011) Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS One 6: e19254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powell W, Morgante M, McDevitt R, Vendramin GG, Rafalski JA (1995) Polymorphic simple sequence repeat regions in chloroplast genomes: applications to the population genetics of pines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 7759–7763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bock R, Khan MS (2004) Taming plastids for a green future. Trends Biotechnol 22: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhong GX, Li P, Zeng LJ, Guan J, Li DQ, et al. (2009) Chemical characteristics of Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen) collected from different locations in China. J Agric Food Chem 57: 6879–6887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang BQ (2010) Salvia miltiorrhiza: Chemical and pharmacological review of a medicinal plant. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 4: 2813–2820. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MS (2005) Danshen: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J Clin Pharmacol 45: 1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng TO (2007) Cardiovascular effects of Danshen. Int J Cardiol 121: 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan E, Tan M, Xin J, Sudarsanam S, Johnson DE (2010) Interactions between traditional Chinese medicines and Western therapeutics. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 13: 50–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li YG, Song L, Liu M, Hu ZB, Wang ZT (2009) Advancement in analysis of Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Danshen). J Chromatogr A 1216: 1941–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li MH, Chen JM, Peng Y, Wu Q, Xiao PG (2008) Investigation of Danshen and related medicinal plants in China. J Ethnopharmacol 120: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hung YC, Wang PW, Pan TL (2010) Functional proteomics reveal the effect of Salvia miltiorrhiza aqueous extract against vascular atherosclerotic lesions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804: 1310–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ma Y, Yuan L, Wu B, Li X, Chen S, et al. (2012) Genome-wide identification and characterization of novel genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza . J Exp Bot 63: 2809–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee CY, Agrawal DC, Wang CS, Yu SM, Chen JJ, et al. (2008) T-DNA activation tagging as a tool to isolate Salvia miltiorrhiza transgenic lines for higher yields of tanshinones. Planta Med 74: 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yan Y-p, Wang Z-z (2007) Genetic transformation of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 88: 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiao Y, Zhang L, Gao S, Saechao S, Di P, et al. (2011) The c4h, tat, hppr and hppd genes prompted engineering of rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures. PLoS One 6: e29713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens PF (2012) Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 12, July 2012. http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/.

- 26. Zhang T, Zhang X, Hu S, Yu J (2011) An efficient procedure for plant organellar genome assembly, based on whole genome data from the 454 GS FLX sequencing platform. Plant Methods 7: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL (2004) Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20: 3252–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM (2005) The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 33: W686–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cui L, Veeraraghavan N, Richter A, Wall K, Jansen RK, et al. (2006) ChloroplastDB: the Chloroplast Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lohse M, Drechsel O, Bock R (2007) OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr Genet 52: 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, et al. (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, et al. (2004) Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol 5: R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I (2004) VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 32: W273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, et al. (2001) REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 4633–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benson G (1999) Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nie X, Lv S, Zhang Y, Du X, Wang L, et al. (2012) Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major invasive species, crofton weed (Ageratina adenophora). PLoS One 7: e36869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swofford DL (2003) PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Posada D, Crandall KA (1998) MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14: 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang X, Madan A (1999) CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res 9: 868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moore MJ, Dhingra A, Soltis PS, Shaw R, Farmerie WG, et al. (2006) Rapid and accurate pyrosequencing of angiosperm plastid genomes. BMC Plant Biol 6: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yi DK, Kim KJ (2012) Complete chloroplast genome sequences of important oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. PLoS One. 7: e35872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mariotti R, Cultrera NG, Diez CM, Baldoni L, Rubini A (2010) Identification of new polymorphic regions and differentiation of cultivated olives (Olea europaea L.) through plastome sequence comparison. BMC Plant Biol 10: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang T, Fang Y, Wang X, Deng X, Zhang X, et al. (2012) The complete chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of Boea hygrometrica: insights into the evolution of plant organellar genomes. PLoS One 7: e30531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim KJ, Lee HL (2004) Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res 11: 247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shinozaki K, Ohme M, Tanaka M, Wakasugi T, Hayashida N, et al. (1986) The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. EMBO J 5: 2043–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tangphatsornruang S, Sangsrakru D, Chanprasert J, Uthaipaisanwong P, Yoocha T, et al. (2010) The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by high-throughput pyrosequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res 17: 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Clegg MT, Gaut BS, Learn GH Jr, Morton BR (1994) Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 6795–6801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bendich AJ (1987) Why do chloroplasts and mitochondria contain so many copies of their genome? BioEssays 6: 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Provan J, Corbett G, McNicol JW, Powell W (1997) Chloroplast DNA variability in wild and cultivated rice (Oryza spp.) revealed by polymorphic chloroplast simple sequence repeats. Genome 40: 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pauwels M, Vekemans X, Gode C, Frerot H, Castric V, et al. (2012) Nuclear and chloroplast DNA phylogeography reveals vicariance among European populations of the model species for the study of metal tolerance, Arabidopsis halleri (Brassicaceae). New Phytol 193: 916–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xue J, Wang S, Zhou SL (2012) Polymorphic chloroplast microsatellite loci in Nelumbo (Nelumbonaceae). Am J Bot 99: e240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rose O, Falush D (1998) A threshold size for microsatellite expansion. Mol Biol Evol 15: 613–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huotari T, Korpelainen H (2012) Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Elodea canadensis and comparative analyses with other monocot plastid genomes. Gene 508: 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Raubeson LA, Peery R, Chumley TW, Dziubek C, Fourcade HM, et al. (2007) Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus . BMC Genomics 8: 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kuang DY, Wu H, Wang YL, Gao LM, Zhang SZ, et al. (2011) Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Magnolia kwangsiensis (Magnoliaceae): implication for DNA barcoding and population genetics. Genome 54: 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Takano A, Okada H (2011) Phylogenetic relationships among subgenera, species, and varieties of Japanese Salvia L. (Lamiaceae). J Plant Res 124: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schaferhoff B, Fleischmann A, Fischer E, Albach DC, Borsch T, et al. (2010) Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences. BMC Evol Biol 10: 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ma XY, Xie CX, Liu C, Song JY, Yao H, et al. (2010) Species identification of medicinal pteridophytes by a DNA barcode marker, the chloroplast psbA-trnH intergenic region. Biol Pharm Bull 33: 1919–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yao H, Song JY, Ma XY, Liu C, Li Y, et al. (2009) Identification of Dendrobium species by a candidate DNA barcode sequence: the chloroplast psbA-trnH intergenic region. Planta Med 75: 667–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kumar S, Hahn FM, McMahan CM, Cornish K, Whalen MC (2009) Comparative analysis of the complete sequence of the plastid genome of Parthenium argentatum and identification of DNA barcodes to differentiate Parthenium species and lines. BMC Plant Biol 9: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Goulding SE, Olmstead RG, Morden CW, Wolfe KH (1996) Ebb and flow of the chloroplast inverted repeat. Mol Gen Genet 252: 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang RJ, Cheng CL, Chang CC, Wu CL, Su TM, et al. (2008) Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol Biol 8: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hirao T, Watanabe A, Kurita M, Kondo T, Takata K (2009) A frameshift mutation of the chloroplast matK coding region is associated with chlorophyll deficiency in the Cryptomeria japonica virescent mutant Wogon-Sugi. Curr Genet 55: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yue F, Cui L, dePamphilis CW, Moret BM, Tang J (2008) Gene rearrangement analysis and ancestral order inference from chloroplast genomes with inverted repeat. BMC Genomics 9 Suppl 1S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Haberle RC, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK (2008) Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes. J Mol Evol 66: 350–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pombert JF, Otis C, Lemieux C, Turmel M (2005) The chloroplast genome sequence of the green alga Pseudendoclonium akinetum (Ulvophyceae) reveals unusual structural features and new insights into the branching order of chlorophyte lineages. Mol Biol Evol 22: 1903–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chumley TW, Palmer JD, Mower JP, Fourcade HM, Calie PJ, et al. (2006) The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium x hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol Biol Evol 23: 2175–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ruhlman T, Lee SB, Jansen RK, Hostetler JB, Tallon LJ, et al. (2006) Complete plastid genome sequence of Daucus carota: implications for biotechnology and phylogeny of angiosperms. BMC Genomics 7: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Samson N, Bausher MG, Lee SB, Jansen RK, Daniell H (2007) The complete nucleotide sequence of the coffee (Coffea arabica L.) chloroplast genome: organization and implications for biotechnology and phylogenetic relationships amongst angiosperms. Plant Biotechnol J 5: 339–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moore MJ, Bell CD, Soltis PS, Soltis DE (2007) Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 19363–19368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leebens-Mack J, Raubeson LA, Cui L, Kuehl JV, Fourcade MH, et al. (2005) Identifying the basal angiosperm node in chloroplast genome phylogenies: sampling one’s way out of the Felsenstein zone. Mol Biol Evol 22: 1948–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Walker JB, Sytsma KJ, Treutlein J, Wink M (2004) Salvia (Lamiaceae) is not monophyletic: implications for the systematics, radiation, and ecological specializations of Salvia and tribe Mentheae. Am J Bot 91: 1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Walker JB, Sytsma KJ (2007) Staminal evolution in the genus Salvia (Lamiaceae): molecular phylogenetic evidence for multiple origins of the staminal lever. Ann Bot 100: 375–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Daniell H (2007) Transgene containment by maternal inheritance: effective or elusive? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 6879–6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Verma D, Daniell H (2007) Chloroplast vector systems for biotechnology applications. Plant Physiol 145: 1129–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Verma D, Samson NP, Koya V, Daniell H (2008) A protocol for expression of foreign genes in chloroplasts. Nat Protoc 3: 739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Boea hygrometrica .

(TIF)

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Olea europaea .

(TIF)

Chloroplast genomic alignment between Salvia miltiorrhiza and Sesamum indicum .

(TIF)

The ML phylogenetic tree (−lnL = 264933.3750) of the asterid clade based on 71 protein-coding genes. The GTR+I+G nucleotide substitution model was adopted based on the Modeltest. Numbers above each node are bootstrap support values. Spinacia oleracea and Arabidopsis thaliana were set as outgroups.

(TIF)

Primers used for assembly validation.

(DOC)

The list of accession numbers of the chloroplast genome sequences used in this study.

(DOC)

Genes present in the Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome.

(DOC)

Size comparison of Salvia miltiorrhiza chloroplast genomic regions with three other Lamiales chloroplast genomes.

(DOC)

Comparison of homologues between the Salvia miltiorrhiza and Boea hygrometrica ( Bh ), Olea europaea ( Oe ) or Sesamum indicum ( Si ) chloroplast genomes using the percent identity of protein-coding sequences.

(DOC)

Average pairwise sequence distance of protein-coding genes among the 30 asterid chloroplast genomes.

(DOC)