Abstract

Background

The presence of cirrhosis increases the potential risk of hemorrhage for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We evaluated the relative risk for hemorrhage in patients with HCC treated with anti-angiogenic agents.

Patients and Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of anti-angiogenic studies in HCC from 1995 to 2011. For non-randomized studies we compared bleeding risk with other HCC single-arm studies which did not include an anti-angiogenic agent. To separate disease-specific factors we also performed a comparison analysis with renal cancer studies which evaluated sorafenib.

Results

Sorafenib was associated with increased bleeding risk compared to control for all grade bleeding events (OR 1.77; 95% CI 1.04, 3.0) but not grade 3–5 events in both HCC and RCC ((OR1.46 95% CI 0.9, 2.36 [p=0.45]). When comparing the risk of bleeding in single-arm phase 2 studies evaluating anti-angiogenic agents, this risk for all events (OR 4.34; 95% CI 2.16, 8.73) was increased compared to control.

Conclusions

This analysis of both randomized and non-randomized studies evaluating an anti-angiogenic agent in HCC showed that whilst the use of sorafenib was associated with an increased risk of bleeding in HCC, this was primarily for lower grade events and similar in magnitude to the risk encountered in RCC.

Introduction

Until recently the role of systemic therapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was minimal. This changed with the publication of the landmark SHARP study in 2008, which resulted in sorafenib becoming the standard of care option for disease that is not amenable to surgery, ablation or chemoembolization (1). While it is true that the median survival advantage in this study was 3 months, its major importance arguably lay in the momentum that it gave to the field, and in particular to the development of so-called ‘anti-angiogenic’ therapies in HCC. However, anti-angiogenic therapies carry their own particular risk profile – including bleeding, hypertension, proteinuria and thrombotic events – and this profile has been further and better defined in the time since the first major study demonstrated proof of principle for their efficacy(2).

In any HCC clinical trial the majority of patients will have underlying cirrhosis and this serves as an additional co-morbidity that must be accounted for in the eligibility criteria and risk assessment. It also increases the baseline risk for a patient entering a study, with a greater potential for overlap between the cirrhosis-related risk and the toxicities of the agent under study. Of particular concern is the risk of bleeding in this patient population, who frequently suffer from portal hypertension and thrombocytopenia. However, there are no standardized eligibility criteria across HCC studies – as regards for example acceptable platelet count and coagulation parameters or mandated endoscopy to detect varices – to safeguard against this added risk of bleeding while at the same time taking into account the fact that HCC patients have baseline parameters that would ordinarily be exclusionary.

We sought to investigate fully the incidence and relative risk of bleeding events in patients with HCC who have been treated with an anti-angiogenic agent, mainly sorafenib, as part of a clinical trial. Our major aim was to ascertain whether in fact the bleeding risk is increased in this patient population being treated with this class of drug. Because the majority of randomized studies in HCC have evaluated sorafenib the greater part of our analysis pertained to this drug. To separate disease-specific factors from potential drug class effect we compared the risk of bleeding in HCC studies with that of randomized studies also evaluating sorafenib in renal carcinoma. We also set out to describe the considerable heterogeneity, which exists with regard to the eligibility criteria for study entry in HCC.

Patients and Methods

Selection of studies

We performed a systematic review of published studies evaluating an anti-angiogenic agent in patients with HCC. The term ‘anti-angiogenic’ was defined as any therapy whose putative mode of action was either wholly or partly directed against the tumor vasculature. To identify relevant clinical trials we conducted a PubMed search of citations from January 1995 to December 31 2011. The search terms employed in our literature search included: ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’, ‘anti-angiogenic’, ‘sorafenib’, ‘sunitinib’, ‘bevacizumab’. For the randomized studies we used the non-treatment groups as control and for the non-randomized single-arm phase 2 studies, which accounted for the majority of the studies, we compared bleeding risk with other HCC single-arm studies not including an anti-angiogenic agent. To separate disease-specific effects we also performed a comparison analysis with renal cancer studies which evaluated sorafenib. We confined our analysis to prospective studies which have been published in manuscript form.

Data analysis

We analyzed studies that met the following criteria: phase 1, 2 or 3 trials in HCC; phase 3 studies evaluating sorafenib in RCC; participants assigned to treatment with an agent whose mechanism of action was known to be wholly or partially anti-angiogenic; adequate safety data available for bleeding events. For every study we extracted the following information: author name; year of publication; number of enrolled patients; treatment; eligibility criteria regarding platelet count, coagulation, hepatic function, Child-Pugh status; endoscopic requirements. Although we sought to evaluate cross-study variability in entry criteria we did include studies where the eligibility criteria were incomplete as this was not the primary aim of our analysis. The occurrence of hemorrhagic events of any grade was recorded. We assessed and recorded adverse events according to the National Cancer Institute’s common toxicity criteria (versions 2.0 or 3.0), which were used by all of the clinical trials.

Statistical analysis

To calculate incidence we extracted from the safety profile the number of bleeding events (all grade and grade 3–5) and the number of patients on the study. For every study we derived the proportion (and 95% confidence interval) of patients with adverse outcomes. For studies which contained a control arm the number of events was entered for both arms and the Mantel-Haenszel method used to calculate an odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. These odds ratios were plotted in a forrest plot where they were assigned a weight, based on sample size and variance, and pooled for an overall effect estimate of anti-angiogenesis therapy on bleeding events. Analysis (using the inverse variance method, alpha of 0.05) and forest plots were generated using R statistical software and Review Manager.

Results

Study demographics

To quantify the risk of hemorrhage associated with the use of anti-angiogenic agents in HCC we performed an analysis of i) randomized studies involving sorafenib in both HCC and RCC (to separate disease-specific effects) and ii) non-randomized studies in HCC involving heterogenous anti-angiogenic therapies, which we compared with similar studies not involving anti-angiogenic therapy. The randomized studies are shown in Table 1 whilst the non-randomized studies involving both angiogenic and non-angiogenic therapies are shown in Table 2 and 3 respectively. Six randomized studies involving a total of N= 2464 patients and which compared sorafenib to control in HCC and RCC were identified. Of the HCC patients, fifty percent were enrolled in either the SHARP study or the Asia-Pacific study. Among the included set of HCC single arm studies, there were 19 treated with anti-angiogenic therapy and 21 treated with non-anti-angiogenic therapy. Eleven of the studies involved sorafenib, four employed bevacizumab and three studies evaluated sunitinib. The remaining studies involved other agents which are reported to have anti-angiogenic effects (brivanib, lenalidomide, TSU68, Linifanib, ramicirumab).

Table 1.

Randomized sorafenib studies in RCC and HCC

| Author | Year | Cancer | Interventions | ID | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abou-Alfa(20) | 2010 | HCC | Sorafenib+Doxorubicin vs. Placebo+Doxorubicin | NCT00108953 | A Randomized Controlled Study of BAY43-9006 in Combination With Doxorubicin Versus Doxorubicin in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. |

| Cheng (21) | 2010 | HCC | Sorafenib vs. Placebo | NCT00492752 | A Randomized, Double-blinded, Placebo-controlled Study of Sorafenib in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. |

| Escudier (22) | 2007 | RCC | Sorafenib vs. Placebo | NCT00073307 | Phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sorafenib in patients with advanced clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). |

| Escudier (23) | 2009 | RCC | Sorafenib vs. Interferon | NCT00117637 | A Randomised, Open-label, Multi-centre Phase II Study of BAY43-9006 (Sorafenib) Versus Standard Treatment With Interferon Alpha-2a in Patients With Unresectable and/or Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| Kudo (24) | 2011 | HCC | Sorafenib vs. Placebo | NCT00494299 | Phase III Study of BAY43-9006 in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Treated After Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization (TACE). |

| Llovet(1) | 2008 | HCC | Sorafenib vs. Placebo | NCT00105443 | A Phase III Randomized, Placebo-controlled Study of Sorafenib in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. |

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria and bleeding experience in HCC studies involving anti-angiogenic therapy.

| Study | Therapy | N | Eligibility Criteria | Prior bleeding or anticoagulation restriction |

Bleeding experience |

Endoscopy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Pugh (CP) status/ liver function or ALT/AST |

Platelet | INR | ||||||

| Llovet et al. (1) | Sorafenib v Placebo | 602 | CP A albumin, ≥2.8 bilirubin, ≤3 ALT/AST ≤5× ULN2 | >60 | <2.3 | No stated restriction | Sorafenib v placebo: 9% v 13% serious hemorrhagic event; 2% v 4% variceal bleeding; 0% v 2% peritoneal hem; 1% v 2% upper GI hem | - |

| Abou-alfa et al. (20) | Sorafenib + doxorubicin v doxorubicin | 96 | CP A bilirubin ≤3 mg/dL, ALT/AST ≤5 × ULN | >75 | NS1 | No stated restriction | doxorubicin-sorafenib v doxorubicin 19.1% v 10.2% any-grade. N=2 G3/ 4 GI bleeding in the doxorubicin-sorafenib group. | - |

| AP study (21) | Sorafenib v Placebo | 271 | CP A albumin ≥28 g/L; total bilirubin ≥51·3 µmol/L; ALT ≤5 × ULN | >60 | <2.3 | Bleeding in previous 30 days excluded. | 4(2.7%) v 3(4%) upper GI hemorrhage– all G1 or G2. No G3/4 hemorrhage | - |

| Abou-alfa et al. (25) | Sorafenib | 137 | CP A/B 72%/28%; minimal other details given; | NS | NS | No comment on ex criteria re: varices or bleeding. | 1 death from intracranial hemorrhage No other bleeding events reported | - |

| Siegel et al. (3) | Bevacizumab | 46 | CP A/compensated B, bilirubin ≤ 3 mg/dL, albumin ≥ 2.5 | >75 | <1.5 | Excluded anticoagulation or antiplatelet tx | Major bleeding in 11% ie G3/4. Protocol amended after 1st bleed. There was also one G 4 hemoperitoneum, and one G3 intratumoral hemorrhage. | If prior varices or evidence of varices on CT/MRI |

| Thomas et al.(4) | Bevacizumab + erlotinib | 40 | CP A/B; PT ≤3s above institutional norm; albumin ≥ 2.5 Bili ≤ 2gm/dL ALT ≤5 × ULN | >40 | ≤3s above ULN | no active GI bleeding in previous 3months | 72% G1/2 pulmonary hemorrhage, nose bleeds. No G3/4. 17.5% G1/2 GI bleeding and 12.5% G3/4/5 bleeding. | Pillcam in patients with any evidence of portal hypertension. |

| Koeberle et al. (26) | Sunitinib | 45 | CP A/B; Bili ≤ 2gm/dL ALT ≤7 × ULN No ascites of any grade. | >75 | NS | no documented variceal bleeding in last 3months | 3 patients with variceal bleed. | - |

| Dufour et al. (27) | Sorafenib + TACE | 14 | CP A/B ALT, AST ≤5 × ULN | >60 | INR ≤1.5 | No anticoagulation | None reported | - |

| Kanai et al. (28) | TSU68 | 35 | CP A/B; bilirubin ≤2.5 mg/dl; AST and ALT ≤ 200U/l; albumin ≥3 g/dl | >75 | PT >40s | Need for ligation/sclerotherapy excluded. | No bleeding events reported. | - |

| Zhu et al. (29) | Sunitinib | 34 | CLIP≤3 | NS | NS | ‘history of bleeding’. | 2(6%) G3 upper GI bleeding. 6(18%) G 1/2 epistaxis. | - |

| Faivre et al. (30) | Sunitinib | 37 | CP A/B bilirubin < 1·25 ULN ALT/AST ≤ 2·5×ULN | NS | - | grade-3 haemorrhage less than 4 weeks before | N=3 G3/4 bleeding: epistaxis, bleeding ascites, varices. N=1 G5 variceal bleed. | - |

| Zhu et al. (31) | Gemcitabine/oxaliplatin/bevacizumab | 33 | CLIP≤3; Bili ≤ 3mg/dL AST ≤ ×7 ULN | >75 | NS | ‘history of active bleeding’ excluded. | N=2 esophageal variceal bleed. N=2 G3 epistaxis, hematochezia | - |

| Hsu et al. (32) | Bevacizumab + capecitabine | 45 | CP A, Bili ≤ 1.2mg/dL ALT ≤ ×5 ULN | >150 | NS | NS | n=4 (9%) GI bleeding (including three patients with oesophageal variceal bleeding) | history of GI bleeding <1 yr or known varices required to undergo EGD. |

| Furuse et al. (33) | Sorafenib (phase I) | 27 | CP A/B Bili ≤ 3mg/dL AST/ALT ≤ ×5 ULN | >75 | PT/APTT ≤×1.5uln | NS | No bleeding events reported | - |

| Worns et al. (34) | Sorafenib in consecutive patients. | 34 | CP A/B/C. Advanced population with 12%C and 44%B | NS | NS | NS | 2 variceal hemorrhages | - |

| Yau et al. (35) | PTK787 (VEGF tki) + doxorubicin | 30 | CP A/B, bili< ×2ULN, AST/ALT <×5uln. | >100 | NS | NS | 2 bleeding complications: 1death from GI bleed and 1 cerebellar bleed. | - |

| Santoro et al. (36) | NGR-hTNF | 27 | CP A/B bilirubin <2-fold ULN, AST/ALT<3-fold ULN | >100 | NS | NS | 1G1 esophageal variceal hemorrhage, 1G2 hemoptysis | - |

| Hsu et al. (37) | Sorafenib + tegafur/uracil | 53 | CP A AST/ALT <×5 ULN. albumin ≥ 2.8 g/dl, bilirubin ≤3 mg/dl, | ≥100 | INR≤ 2.3 | GI bleeding <30 days prior. | N=4 G3/4 GI bleeding (3=esophageal varices, 1=gastric ulcer). | - |

| Prete et al. (38) | Sorafenib + octreotide | 50 | Child-Pugh A/B, bilirubin ≤ 3 mg/dl, albumin ≤2.5 | ≥60 | NS | History of active bleeding excluded | N=3 (6%) G1 bleeding, not specified. | If clinically indicated. |

| Yau et al. (39) | sorafenib | 51 | Minimal eligibility Advanced Hep B population | NS | NS | NS | N=3 hemorrhage; (1 epistaxis, 2 upper GI) | - |

| Richly et al. (40) | Sorafenib + doxorubicin | 18 | CP status NS bilirubin <1.5 × ULN; ALT/AST ≤2.5 × ULN | ≥100 | PT≤1.5 × ULN | NS | N=1 G3 hemorrhage, not specified, ‘associated with surgery’ | - |

| Cappa et al. (41) | Thalidomide, megace, IL-2 | 9 | A/B/C Bilirubin ≥ 5mg/dl | NS | NS | NS | No bleeding events | - |

| Petrini et al.(42) | Sorafenib + 5FU | 39 | Child-Pugh A/B | clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding within 1 month from the enrollment were not eligible | ||||

Table 3.

Single-arm ‘non-anti-angiogenic’ studies in HCC

| Author | cancer | Therapy | 1Outcome (m) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanoff(43) | HCC | Cap/Ox/Cetux | 3.3 | PFS | 29 |

| Alberts(44) | HCC | Gem/docetaxel | 2.7 | PFS | 25 |

| O'Neil(45) | HCC | AZD6244 | 1.4 | PFS | 19 |

| Lombardi(46) | HCC | Lipos dox/gemcitabine | 5.8 | TTP | 41 |

| Furuse(47) | HCC | S-1 | 3.7 | PFS | 26 |

| Kim(48) | HCC | Bortezomib | 1.6 | TTP | 35 |

| Yang(49) | HCC | Pegylated deiminase | 2.8 | duration disease control | 77 |

| Greten(50) | HCC | Telomerase vaccine | 1.87 | TTP | 40 |

| Glazer(51) | HCC | Pegylated deiminase | None | 80 | |

| Bekaii-Saab(52) | HCC | Iapatinib | 1.9 | PFS | 26 |

| Lin(53) | HCC | Arsenic | 4.8 | PFS | 29 |

| Yen(54) | HCC | Oxaliplatin | 2 | TTP | 36 |

| Uhm(55) | HCC | Oxaliplatin+doxorubicin | 7.75 | PFS | 40 |

| Chia(56) | HCC | Gemcitabine+cisplatin | 1.5 | TTP | 15 |

| Higginbotham(57) | HCC | TAC-101 | 3.2 | PFS | 33 |

| Yuan(58) | HCC | Etoposide,cisplatin,doxorubicin,FU/LV | 3.3 | TTP | 66 |

| Keam(59) | HCC | 5FU, cisplatin | 2.4 | TTP | 57 |

| Asnacios(60) | HCC | Gemcitabine,oxaliplatin,cetuximab | 4.7 | PFS | 45 |

| Lin(61) | HCC | Imatinib | 1.15 | TTP | 15 |

| Cohn(62) | HCC | Pemetrexed | None | 21 | |

| Knox(63) | HCC | SB715992 | 1.6 | TTP | 15 |

PFS or TTP used as surrogate for period of follow-up evaluation unless stated.

Eligibility criteria

There was marked variability across all the studies with regard to the stated laboratory eligibility criteria for entry onto the study. As illustrated in Table 2, the required platelet count ranged from 40 to 150 and INR from 1 to 2.3. The two largest studies, the SHARP and AP studies, allowed for a platelet count of greater than or equal to 60,000. Six of the studies restricted entry to Childs-Pugh A patients only. No study was identified which mandated endoscopy to exclude patients with varices. However, after the occurrence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the course of two studies (3, 4) (in one case, a fatal variceal hemorrhage), the protocol was amended to require screening endoscopy prior to inclusion in the study in patients with any evidence of portal hypertension. Patients found to have esophageal varices on screening examination were eligible for the study following adequate treatment with banding or sclerotherapy and repeat endoscopy showing the varices to be obliterated, minimal, or grade 1.

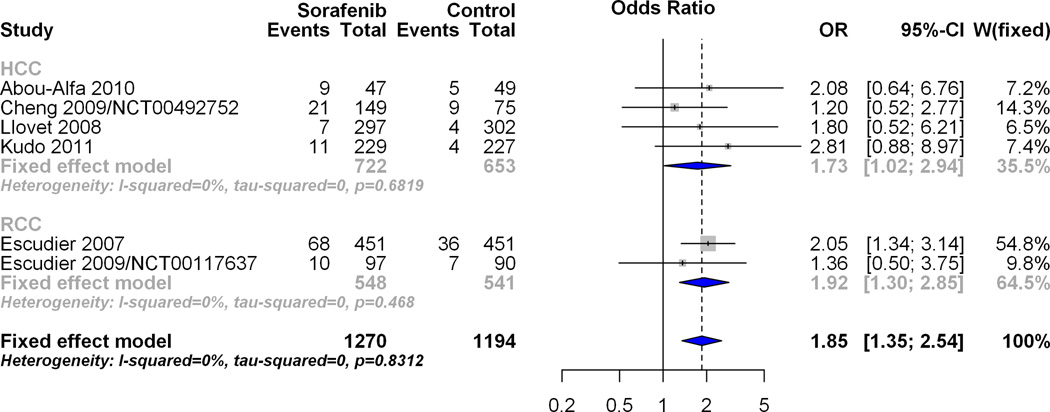

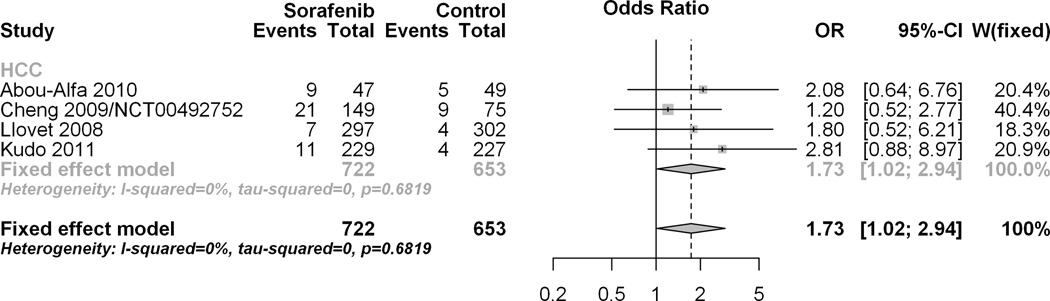

Effect of Sorafenib on odds of bleeding event as compared to control in HCC randomized studies

There were four HCC randomized studies involving Sorafenib. The forest plot in figure 1A visually depicts the pooled overall estimate of the effect of Sorafenib on all bleeding events within HCC randomized studies. The number of events for the Sorafenib arm was 48/722 (6.65%) and was 22/653 (3.37%) for the control arm, giving an odds ratio of 1.77 (95% CI 1.04, 3.0) for both the fixed and random effects models. This result provides evidence of a significant (p=0.04) increase in the odds of bleeding events (all grades) with Sorafenib compared to control. Figure 1B visually depicts the pooled overall estimate of the effect of Sorafenib on grades 3–5 bleeding events within HCC randomized studies. The number of events for the Sorafenib arm was 33/722 (4.57%) and 13/653 (1.99%) for the control arm, giving an odds ratio (95% CI) of 1.76 (0.91, 3.41) for both the fixed and random effects models. This result provides evidence that Sorafenib did not significantly increase (p=0.11) the odds of bleeding events (grades 3–5) as compared to a non-anti-angiogenic control.

Figure 1.

A: Overall hemorrhagic risk for randomized HCC studies. The forest plot visually depicts the pooled overall estimate of the effect of Sorafenib on all-grade bleeding events within HCC randomized studies.

B: Grade 3–5 bleeding events for HCC studies containing control arm. The forest plot visually depicts the pooled overall estimate of the effect of Sorafenib on grade 3–5 bleeding events within HCC randomized studies.

Odds Ratios for bleeding event between anti-angiogenic and non- anti-angiogenic single arm studies in HCC

To examine the risk of bleeding event in anti-angiogenic therapy compared to non-anti-angiogenic therapy among single arm studies in HCC, 19 studies incorporating anti-angiogenic therapy and 21-with non-anti-angiogenic therapy (Table 2 and Table 3) were anlayzed. Figure 2 shows that, among single arm HCC studies, the odds ratio for any bleeding event with anti-angiogenic therapy is 4.34 (2.16, 8.73; p<.0001). The odds ratio of bleeding event grades 3–5 for anti-angiogenic therapy are 2.66 (95% CI 1.03, 6.82; p=.0425). This suggests that anti-angiogenic therapy significantly increases the odds of bleeding events (both all grades and grades 3–5) as compared to non-anti-angiogenic therapy in single arm HCC studies.

Figure 2.

Effect of anti-angiogenic therapy on hemorrhagic risk in single arm HCC studies. Using a logistic regression to model the odds of any bleeding event the forrest plot below indicates the odds ratio of all grade and grade 3–5 bleeding event for antiangiogenic therapy compared to non-antiangiogenic therapy among single arm HCC studies. This estimate is significant as the 95% confidence interval excludes 1 (p<.0001).

Effect of Sorafenib on odds of bleeding event as compared to control in renal cell cancer (RCC) and HCC randomized studies

In order to determine if the observed trend towards increased hemorrhagic risk was inherent to HCC or was a class effect we examined the effect of Sorafenib on bleeding events in RCC. Among the RCC randomized studies, treatment with Sorafenib significantly increased the odds of any bleeding event, (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.30, 2.85) compared to control. The test for subgroup differences showed the effect of Sorafenib on any bleeding event to be similar between the HCC and RCC subgroups [p=0.75]. Similar to the HCC result, treatment with Sorafenib did not significantly increase the odds of bleeding events grades 3–5 (OR 1.18 95% CI 0.58 to 2.38) among the RCC randomized studies. The overall pooled estimate of HCC and RCC studies also indicates a non-significant effect of Sorafenib on bleeding events grades 3–5 (OR1.43 95% CI 0.88, 2.32) which was similar for both HCC and RCC subgroups [p=0.45].

Discussion

Worldwide, HCC is the fifth most common malignancy with a median survival of 6–9 months(5). In the United States the incidence of HCC continues to rise, a trend which will likely result in more clinical trials being performed in this disease(6, 7). In addition, after decades of negative studies in HCC the SHARP and AP studies provided an impetus for the investigation of ‘anti-angiogenic’ strategies in HCC in an effort to bolster the relatively small gains made with sorafenib. We have learned however from the experience in other tumor types that anti-VEGF therapies are associated with class toxicities, including bleeding. In one meta-analysis of bevacizumab-related toxicities hemorrhagic events accounted for almost one quarter of the fatal adverse events seen(8). In HCC this is a particular concern because of the almost invariable presence of cirrhosis in this patient population, placing them at an elevated baseline risk of hemorrhage. The main purpose of this analysis was to determine if there was an increased risk of bleeding for a patient with HCC taking part in a study evaluating an anti-angiogenic therapy. For comparison we also performed an analysis of studies evaluating sorafenib in renal cancer. Both analyses show that whilst the use of sorafenib was associated with an increased risk of bleeding in HCC, this was primarily for lower grade events and similar in magnitude to the risk encountered in RCC. Whilst the nature of these low-grade events for the most part were not characterized, they were defined as grade 1 or 2, meaning that by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) definition they did not require transfusion or endoscopic intervention. We also set out to describe the heterogeneity with regard to the eligibility criteria employed across HCC trials for study entry as these are reflective of baseline risk and are non-standardized in HCC compared to other solid tumors.

A major drawback of this analysis is the fact that only four of the HCC studies contained a control arm. When we confined our analysis to randomized studies – all of which involved sorafenib – there was a significant (p=0.04) increase in the odds of bleeding events of (OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.02, 2.94) associated with Sorafenib compared to control, although this increased risk appeared to be confined to lower grade events. To ascertain whether this was a disease-specific effect we also analyzed the hemorrhagic risk in studies evaluating sorafenib in RCC and found the risk to be similarly increased (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.30, 2.85) suggesting that this is not necessarily greater in HCC patients beyond the effect of the drug itself. Given that the majority of studies evaluating an anti-angiogenic agent in HCC are single-arm, non-randomized phase 2 trials it is very difficult to estimate the overall bleeding risk in these studies, especially given the heterogeneity of treatments administered. To address this, at least partially, we performed a comparative analysis with a group of single-arm phase 2 studies which did not include therapy considered to be anti-angiogenic. We acknowledge the limitations of this approach, and certainly one cannot draw conclusions on causal effects from these uncontrolled studies evaluating heterogeneous agents. Since our outcome is one of safety however, we felt that the phase II single arm studies could provide valid additional data. The results were instructive in that patients with HCC taking part in these studies appeared to have a significantly increased the risk of all-grade bleeding compared to non-anti-angiogenic therapy. It must be emphasized however that sorafenib is the only approved agent for HCC. From a biological standpoint although we do not know whether the benefit of sorafenib is predominantly related to its signal transduction inhibition versus its anti-angiogenic properties it seems likely – by association rather than direct proof – that the hemorrhagic risk is related to its anti-VEGF effect(9, 10). It is known that VEGF has an important role in the maintainance of architectural integrity within the endothelial cells of the microvasculature, inhibition of which may induce the increased risk of bleeding.

A related aim of our analysis was also to describe the variability in eligibility criteria used across studies with regard to both laboratory criteria – which are necessarily different from studies in other diseases – and the requirements with regard to allowing for, or out-ruling, known or suspected varices. This is an important practical consideration as we attempt to improve the quality of studies in HCC and minimize risk. None of the studies mandated an upper endoscopy be performed in order to screen for the presence of varices, although two studies did introduce this after the occurrence of a serious hemorrhage. The risk of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis is difficult to quantify but has been reported to be as high as 40%(11). In the context of HCC the short to medium-term risk is particularly important to assess given that in the SHARP study the median duration of sorafenib treatment was 5.3 months and the median overall survival for these patients was 10.7 months. The presence of even small varices is a marker of increased bleeding risk as shown by one prospective study where (12) the two-year risk of bleeding was found to be significantly higher in patients with small varices at enrollment compared to those who did not have any varices (12% v 2%). Several factors have been employed to predict the risk of variceal hemorrhage, including the size and location of varices (gastric fundus varices of higher risk(13)), their physical appearance and variceal pressure as measured by endoscopic gauge (14). The NIEC study established a prognostic index - depending on size, presence of red wale marks and Child class - which quantified one-year bleeding risk, a relevant time point for a patient with a diagnosis of advanced HCC(15). According to that study there are "high risk" small varices (those that occur in Child C patients or have red wale marks) that may have the same risk of bleeding than a Child A patient with large varices (and prophylaxis is recommended in these patients). Limiting eligibility in HCC studies to Childs A patients – as recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)(16) – would mitigate some of this risk, but – also consistent with current AASLD guidelines(17) – Child A patients should undergo screening endoscopy unless they have had one in the last 2–3 years (with no varices demonstrated) or last 1–2 years (if small varices had been identified. Five of the studies we reviewed – including both the SHARP and AP studies – were confined to patients with Childs-Pugh grade A cirrhosis. Perhaps the most specific indicator of risk for variceal bleeding is the prior occurrence of a hemorrhagic event with the risk of a subsequent bleeding episode estimated to be 17–40%(18) but also, in older analyses, as high as 70%(19). Seven of the studies in our analysis excluded patients with a history of active bleeding, although the duration of this was variable, ranging from 30 days to 1 year. Given that there are effective therapies to prevent first variceal hemorrhage and also recurrent hemorrhage, patients enrolled in these studies should be screened and treated accordingly, with eligibility being confirmed on subsequent endoscopy – as in the study by Thomas et al. – if the varices are found to be ‘obliterated, minimal, or grade 1.’

While the risk of hemorrhagic event in studies evaluating an anti-angiogenic agent in HCC appears to be not significantly raised for serious (grade 3–5) events, there are no standardized across-study eligibility criteria for this ‘at risk’ population in terms of platelet count, prothrombin time or endoscopic requirements. The eligibility criteria for HCC studies tend to be different from other settings to allow for the hepatic dysfunction that is generally present. For example, the SHARP study required a platelet count of greater than 60,000. Future studies will need to address this issue in more detail, particularly when multiple vascular targeting agents are combined.

In summary, this analysis of both randomized and non-randomized studies evaluating an anti-angiogenic agent in HCC showed that whilst the use of sorafenib was associated with an increased risk of bleeding in HCC, this was primarily for lower grade events and similar in magnitude to the risk encountered in RCC.

Figure 3.

A: Overall pooled effect estimate of all bleeding events in the HCC subgroup and RCC subgroup combined. To examine the effect of Sorafenib on bleeding events in RCC and to compare it with the effect in HCC, data was analyzed for all grade bleeding events with HCC and RCC as distinct subgroups. Individual study level effects, pooled subgroup estimates (within each cancer type) and the overall effect were determined and plotted for the RCC subgroup along with results from the tests for subgroup differences which compare the effect of Sorafenib in HCC with the effect of Sorafenib in RCC.

B: Overall pooled effect estimate of bleeding events grades 3–5 in the HCC subgroup and RCC subgroup combined. To examine the effect of Sorafenib on bleeding events in RCC and to compare it with the effect in HCC, data was analyzed for grade 3–5 bleeding events with HCC and RCC as distinct subgroups. Individual study level effects, pooled subgroup estimates (within each cancer type) and the overall effect were determined and plotted for the RCC subgroup along with results from the tests for subgroup differences which compare the effect of Sorafenib in HCC with the effect of Sorafenib in RCC.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Tito Fojo for his helpful comments.

Financial support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel AB, Cohen EI, Ocean A, Lehrer D, Goldenberg A, Knox JJ, Chen H, et al. Phase II trial evaluating the clinical and biologic effects of bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2992–2998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MB, Morris JS, Chadha R, Iwasaki M, Kaur H, Lin E, Kaseb A, et al. Phase II trial of the combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib in patients who have advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:843–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37(Suppl 2):S88–S94. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranpura V, Hapani S, Wu S. Treatment-Related Mortality With Bevacizumab in Cancer Patients: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 305:487–494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1788–1795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilickap S, Abali H, Celik I. Bevacizumab, bleeding, thrombosis, and warfarin. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.046. author reply 3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grace ND. Prevention of initial variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992;21:149–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, Attili AF, et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266–272. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343–1349. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merkel C, Bolognesi M, Berzigotti A, Amodio P, Cavasin L, Casarotto IM, Zoli M, et al. Clinical significance of worsening portal hypertension during long-term medical treatment in patients with cirrhosis who had been classified as early good-responders on haemodynamic criteria. J Hepatol. 52:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, Sherman M, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698–711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funakoshi N, Segalas-Largey F, Duny Y, Oberti F, Valats JC, Bismuth M, Daures JP, et al. Benefit of combination beta-blocker and endoscopic treatment to prevent variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 16:5982–5992. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abou-Alfa GK, Johnson P, Knox JJ, Capanu M, Davidenko I, Lacava J, Leung T, et al. Doxorubicin Plus Sorafenib vs Doxorubicin Alone in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 304:2154–2160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escudier B, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, Demkow T, Staehler M, Rolland F, Negrier S, et al. Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with sorafenib versus interferon Alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo M, Imanaka K, Chida N, Nakachi K, Tak WY, Takayama T, Yoon JH, et al. Phase III study of sorafenib after transarterial chemoembolisation in Japanese and Korean patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 47:2117–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293–4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koeberle D, Montemurro M, Samaras P, Majno P, Simcock M, Limacher A, Lerch S, et al. Continuous Sunitinib treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver (SASL) multicenter phase II trial (SAKK 77/06) Oncologist. 15:285–292. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dufour JF, Hoppe H, Heim MH, Helbling B, Maurhofer O, Szucs-Farkas Z, Kickuth R, et al. Continuous Administration of Sorafenib in Combination with Transarterial Chemoembolization in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results of a Phase I Study. Oncologist. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanai F, Yoshida H, Tateishi R, Sato S, Kawabe T, Obi S, Kondo Y, et al. A phase I/II trial of the oral antiangiogenic agent TSU-68 in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu AX, Sahani DV, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Ancukiewicz M, Catalano OA, Sindhwani V, et al. Efficacy, safety, and potential biomarkers of sunitinib monotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3027–3035. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faivre S, Raymond E, Boucher E, Douillard J, Lim HY, Kim JS, Zappa M, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase II study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:794–800. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu AX, Blaszkowsky LS, Ryan DP, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, Horgan K, Sheehan S, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1898–1903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu CH, Yang TS, Hsu C, Toh HC, Epstein RJ, Hsiao LT, Chen PJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of bevacizumab plus capecitabine as first-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 102:981–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furuse J, Ishii H, Nakachi K, Suzuki E, Shimizu S, Nakajima K. Phase I study of sorafenib in Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Worns MA, Weinmann A, Pfingst K, Schulte-Sasse C, Messow CM, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Teufel A, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in consideration of concomitant stage of liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:489–495. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818ddfc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yau T, Chan P, Pang R, Ng K, Fan ST, Poon RT. Phase 1–2 trial of PTK787/ZK222584 combined with intravenous doxorubicin for treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: implication for antiangiogenic approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 116:5022–5029. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santoro A, Pressiani T, Citterio G, Rossoni G, Donadoni G, Pozzi F, Rimassa L, et al. Activity and safety of NGR-hTNF, a selective vascular-targeting agent, in previously treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 103:837–844. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu CH, Shen YC, Lin ZZ, Chen PJ, Shao YY, Ding YH, Hsu C, et al. Phase II study of combining sorafenib with metronomic tegafur/uracil for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 53:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prete SD, Montella L, Caraglia M, Maiorino L, Cennamo G, Montesarchio V, Piai G, et al. Sorafenib plus octreotide is an effective and safe treatment in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicenter phase II So.LAR. study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 66:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1226-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yau T, Chan P, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Fan ST, Poon RT. Phase 2 open-label study of single-agent sorafenib in treating advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatitis B-endemic Asian population: presence of lung metastasis predicts poor response. Cancer. 2009;115:428–436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richly H, Schultheis B, Adamietz IA, Kupsch P, Grubert M, Hilger RA, Ludwig M, et al. Combination of sorafenib and doxorubicin in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from a phase I extension trial. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cappa FM, Cantarini MC, Magini G, Zambruni A, Bendini C, Santi V, Bernardi M, et al. Effects of the combined treatment with thalidomide, megestrol and interleukine-2 in cirrhotic patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. A pilot study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrini I, Lencioni M, Ricasoli M, Iannopollo M, Orlandini C, Oliveri F, Filipponi F, et al. A phase II (PhII) trial of sorafenib (S) in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5FU) continuous infusion (c.i.) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Preliminary data. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2009;27:4592-. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanoff HK, Bernard S, Goldberg RM, Morse MA, Garcia R, Woods L, Moore DT, et al. Phase II Study of Capecitabine, Oxaliplatin, and Cetuximab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 4:78–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alberts SR, Reid JM, Morlan BW, Farr GH, Camoriano JK, Johnson DB, Enger JR, et al. Gemcitabine and Docetaxel for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Phase II North Central Cancer Treatment Group Clinical Trial. Am J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318219863b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Neil BH, Goff LW, Kauh JS, Strosberg JR, Bekaii-Saab TS, Lee RM, Kazi A, et al. Phase II study of the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2 inhibitor selumetinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 29:2350–2356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardi G, Zustovich F, Farinati F, Cillo U, Vitale A, Zanus G, Donach M, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and gemcitabine in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a phase 2 study. Cancer. 117:125–133. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furuse J, Okusaka T, Kaneko S, Kudo M, Nakachi K, Ueno H, Yamashita T, et al. Phase I/II study of the pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy of S-1 in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 101:2606–2611. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim GP, Mahoney MR, Szydlo D, Mok TS, Marshke R, Holen K, Picus J, et al. An international, multicenter phase II trial of bortezomib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 30:387–394. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang TS, Lu SN, Chao Y, Sheen IS, Lin CC, Wang TE, Chen SC, et al. A randomised phase II study of pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) in Asian advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 103:954–960. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greten TF, Forner A, Korangy F, N'Kontchou G, Barget N, Ayuso C, Ormandy LA, et al. A phase II open label trial evaluating safety and efficacy of a telomerase peptide vaccination in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 10:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glazer ES, Piccirillo M, Albino V, Di Giacomo R, Palaia R, Mastro AA, Beneduce G, et al. Phase II study of pegylated arginine deiminase for nonresectable and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 28:2220–2226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bekaii-Saab T, Markowitz J, Prescott N, Sadee W, Heerema N, Wei L, Dai Z, et al. A multi-institutional phase II study of the efficacy and tolerability of lapatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5895–5901. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin CC, Hsu C, Hsu CH, Hsu WL, Cheng AL, Yang CH. Arsenic trioxide in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II trial. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yen Y, Lim DW, Chung V, Morgan RJ, Leong LA, Shibata SI, Wagman LD, et al. Phase II study of oxaliplatin in patients with unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent hepatocellular cancer: a California Cancer Consortium Trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:317–322. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318162f57d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uhm JE, Park JO, Lee J, Park YS, Park SH, Yoo BC, Paik SW, et al. A phase II study of oxaliplatin in combination with doxorubicin as first-line systemic chemotherapy in patients with inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:929–935. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chia WK, Ong S, Toh HC, Hee SW, Choo SP, Poon DY, Tay MH, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin in inoperable or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:554–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higginbotham KB, Lozano R, Brown T, Patt YZ, Arima T, Abbruzzese JL, Thomas MB. A phase I/II trial of TAC-101, an oral synthetic retinoid, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1325–1335. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0406-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan JN, Chao Y, Lee WP, Li CP, Lee RC, Chang FY, Yen SH, et al. Chemotherapy with etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2008;25:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s12032-007-9013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keam B, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, et al. A Phase II study of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin systemic chemotherapy for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma with alpha fetoprotein as a predictive and prognostic marker. Mol Med Report. 2008;1:415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asnacios A, Fartoux L, Romano O, Tesmoingt C, Louafi SS, Mansoubakht T, Artru P, et al. Gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (GEMOX) combined with cetuximab in patients with progressive advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a multicenter phase 2 study. Cancer. 2008;112:2733–2739. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin AY, Fisher GA, So S, Tang C, Levitt L. Phase II study of imatinib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:84–88. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181131db9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohn AL, Myers JW, Mamus S, Deur C, Nicol S, Hood K, Khan MM, et al. A phase II study of pemetrexed in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knox JJ, Gill S, Synold TW, Biagi JJ, Major P, Feld R, Cripps C, et al. A phase II and pharmacokinetic study of SB-715992, in patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: a study of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG IND.168) Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]