Abstract

Previous research reveals that older adults sometimes show enhanced processing of emotionally positive stimuli relative to negative stimuli, but that this positivity bias reverses to become a negativity bias when cognitive control resources are less available. In this study, we test the hypothesis that emotionally positive feedback will attenuate well-established age-related deficits in rule learning while emotionally negative feedback would amplify age deficits—but that this pattern would reverse when the task involved a high cognitive load. Experiment 1 used emotional face feedback and revealed an interaction between age, valence of the feedback and task load. When the task placed minimal load on cognitive control resources, happy face feedback attenuated age-related deficits in initial rule learning and angry face feedback led to age-related deficits in initial rule learning and set shifting. However, when the task placed a high load on cognitive control resources, we found that angry face feedback attenuated age-related deficits in initial rule learning and set shifting, whereas happy face feedback led to age-related deficits in initial rule learning and set shifting. Experiment 2 used less emotional point feedback and revealed age-related deficits in initial rule learning and set shifting under low and high cognitive load for point gain and point loss conditions. The present research demonstrates that emotional feedback can attenuate age-related learning deficits – but only positive feedback for tasks with a low cognitive load and negative feedback for tasks with high cognitive load.

Keywords: normal aging, learning, set shifting, emotional processing

Introduction

Currently, one in eight people in the United States are above the age of 65, and this number is expected to increase to one in five by the year 2030 (Census data, 2010). Technological advancements, as well as the need to defer retirement in the current economic climate, underscore the importance of continued learning throughout life. Age-related deficits in learning are well documented. Older adults often have particular trouble learning tasks that rely on executive function and cognitive control mechanisms (Braver & Barch, 2002; Park et al., 2002; Salthouse, 2004; Verhaeghen & Cerella, 2002; Verhaeghen, Steitz, Sliwinski, & Cerella, 2003; however see Verhaeghen, 2011). For example, older adults generally struggle in a broad range of rule learning and set shifting tasks, such as the classic Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST; Head, Kennedy, Rodrigue, & Raz, 2009; Gunning-Dixon & Raz, 2003; MacPherson, Phillips, & Sala, 2002).

Despite well-documented learning deficits associated with normal aging, older adults’ affective processing is generally well preserved (Leclerc & Kensinger, 2008; Mather, 2012). Older adults continue to have strong emotional experiences and report enhanced emotional well-being when compared with younger adults (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Kobau, Safran, Zack, Moriarty, & Chapman, 2004). Interestingly, whether older adults process positive or negative emotional information more effectively can differ as a function of available cognitive control resources. Specifically, when cognitive control resources are available, older adults show enhanced processing of positive emotional information (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005; Petrican, Moscovitch, & Schimmack, 2008); however this tendency can reverse to favor negative information when cognitive control resources are less available (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005).

The goal of the present study is to explore the possibility that age-related enhancements in the processing of emotional information might be leveraged to attenuate or even reverse some well-established age-related deficits in learning. The social and cognitive neuroscience literatures suggest considerable overlap between set shifting and emotional processing, making this a possibility worth exploring (Davidson & Irwin, 1999; Monchi, Petrides, Petre, Worsley, & Dagher, 2001; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). For example, the WCST, a well-studied set shifting task, is known to place large demands on lateral frontal regions such as the dosolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Monchi et al., 2001). These same regions have been shown to be involved in the processing of emotional information (Ochsner et al., 2004; Anderson et al., 2003; Öhman et al., 2001). Thus, emotion processing centers in the lateral prefrontal cortex may compete for resources during set shifting.

We focus on a learning task that relies on executive function and is similar to the popular Wisconsin Card Sort Task (WCST). The task requires participants to learn rules (initial rule learning) and, once the rule is learned, to switch from a learned to a novel rule (set shifting). Our approach is to compare learning under conditions where trial-by-trial feedback is highly emotional, presented in the form of happy or angry faces, with conditions where trial-by-trial feedback is less emotional, presented in the form of point gain or point loss. (In the appendix, we present the results from a small-scale pilot study that verifies that face feedback is perceived as more emotional than point feedback.) To foreshadow, our results suggest that age-related deficits in rule learning and set shifting are more malleable than previously thought. Under the appropriate feedback conditions, age-related deficits can be attenuated. The age-related effects on learning depend upon a systematic interaction between the cognitive-control demands of the task and the emotional valence of the feedback.

Age-Related Learning Deficits

Age-related performance deficits are seen across a multitude of cognitive domains including inductive reasoning, spatial orientation, perceptual speed, numeric ability, verbal ability, and memory (Schaie, 1996). Normal aging is also associated with declines in learning, especially for tasks that rely on executive functions such as working memory and attention (Braver & Barch, 2002; Park et al., 2002; Salthouse, 2004; Verhaeghen & Cerella, 2002; Verhaeghen et al., 2003). These include many forms of rule-based category learning (Maddox, Pacheco, Reeves, Zhu, & Schnyer, 2010; Racine, Barch, Braver, & Noelle, 2006), as well as tasks that require set shifting (Gunning-Dixon & Raz, 2003; Head et al., 2009; MacPherson et al., 2002). Because of the prevalence of rule-based learning and set shifting in everyday life, it would be highly advantageous to develop task-specific feedback training protocols that enhance these forms of learning in older adults. This is the overriding aim of the present study.

Cognitive Control and Emotional Processing in Older Adults

Older adults process positive emotional content more deeply than negative emotional content compared to younger adults, an age difference known as the ‘positivity effect’ (Mather & Carstensen, 2005). Although the positivity effect is not always observed (e.g. see Grühn, Scheibe, & Baltes, 2007; Murphy & Isaacowitz, 2008), it is frequently seen in the domains of choice (Mather, Knight, & McCaffrey, 2005), attention (Isaacowitz, 2006; Mather & Carstensen, 2003), and memory (Grady, Hongwanishkul, Keightley, Lee, & Hasher, 2007; Kennedy, Mather, & Carstensen, 2004). For instance, when shown positive, negative, and neutral pictures, older adults recall more positive pictures and fewer negative pictures than younger adults (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003).

Mather and colleagues argue that older adults’ positivity bias is the result of goal-directed processes and thus depends on cognitive control resources and executive function processes (Kryla-Lighthall & Mather, 2009; Mather & Knight, 2005; Nashiro, Sakaki, & Mather, 2012). Reduced cognitive control resources should attenuate the positivity effect in attention and memory. Mather and Knight (2005) tested this hypothesis by having older adults view pictures under full attention conditions, or with a secondary task that divided attention and required working memory resources. In the full attention condition, older adults recalled more positive than negative pictures, whereas younger adults recalled more negative than positive pictures. This is consistent with a positivity effect. However, in the divided attention condition, both groups recalled more negative pictures than positive pictures. Other results suggesting that cognitive control processes contribute to the positivity effect have been observed by Knight et al. (2007), Isaacowitz et al. (2009), Petrican et al., (2008), and Orgeta (2011).

The Present Research

The goal of the present research is to determine whether enhanced emotional processing in older adults can be used to attenuate well-established age-related learning deficits. We use highly emotional information in the form of happy or angry faces as feedback during learning. In the ‘happy face feedback’ condition, a correct response is followed by the presentation of a very happy face, whereas an incorrect response is followed by the presentation of a mildly happy face. In the ‘angry face feedback’ condition, a correct response is followed by the presentation of a mildly angry face, whereas an incorrect response is followed by the presentation of a very angry face.

The present research used a very general learning task that was modeled after the classic Wisconsin Card Sort Task (Heaton, 1980). The task allowed us to examine age and emotional feedback effects separately on initial rule learning and following a rule switch (i.e., set shifting). We manipulated the cognitive-control demands associated with the learning task directly, by manipulating the number of stimulus dimensions and the number of categories, thus creating a low and a high cognitive control load version of the task (see Method for details). We predicted an interaction between the valence of the face feedback (happy vs. angry) and the cognitive-control demands of the learning task (low vs. high) on age-based differences in performance. In the low-load version of the task, we predicted that older adults would have enough cognitive-control resources available to enhance positive emotional feedback processing in the happy-face-feedback condition, thus attenuating age-related learning deficits, whereas large age-related deficits would be observed in the angry-face-feedback condition. On the other hand, in the high load version of the task, we predicted that older adults would not have enough cognitive control resources available to enhance positive emotional feedback processing. Instead, they would show enhanced negative emotional feedback processing, thus attenuating age-related learning deficits in the angry-face-feedback condition, whereas large age-related deficits would be observed in the happy-face-feedback condition.

A relevant study by Nashiro and colleagues (Nashiro, Mather, Gorlick, & Nga, 2011) used a simple learning task in which older and younger participants were presented with two neutral faces on each trial. Participants were asked to choose the face that would change into a happy face, or avoid the face that would change into an angry face. After 5-8 consecutive correct trials, the correct face switched unbeknownst to the participant. Older adults made significantly more errors than younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition but were statistically equal to younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition. This task involves only two relevant stimuli placing low demand on cognitive control. As predicted, when cognitive control resources were available happy face feedback attenuated age-related learning deficits.

This is an important study that yielded promising results. Even so, it leaves several gaps in our understanding. Nashiro et al. used faces as both the categorized stimuli and feedback therefore it is unclear whether these results would generalize to stimuli that were not intrinsically associated with the feedback. Second, Nashiro et al. focuses only on a simple low load condition. In our day-to-day lives learning is often comprised of more complex tasks that depend on competing neural networks. Research suggests that cognitive load is critical for emotional biases, however to date no research has directly compared the impact of cognitive load on age-related learning differences given emotional feedback. Finally, Nashiro et al. focused on one overall measure of performance (number of errors), however we can learn more about what phase of learning is driving these effects by breaking performance down into initial rule learning and set shifting.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 examined age-related changes in rule learning and set shifting as a function of the valence of emotional face feedback (happy vs. angry), as well as that of the cognitive load (low vs. high) associated with solving the task. To determine whether the emotional aspect of the face feedback was critical, Experiment 2 serves as a replication of Experiment 1, but with the emotional face feedback replaced with less emotional point feedback.

Method

Participants

Thirty older adults (Age: MOldLow= 66.87; RangeOldLow= 60-79) and 37 younger adults (Age: MYoungLow= 21.74; RangeYoungLow= 18-35) participated in the low-cognitive-load condition, and 36 older adults (Age: MOldHigh= 66.67; RangeOldHigh= 60-82) and 40 younger adults (Age: MYoungHigh= 20.08; RangeYoungHigh= 18-26) participated in the high-cognitive-load condition for monetary compensation. Older adults were given a large battery of neuropsychological tests during a prescreening session including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth (Wechsler, 1997), Stroop test (Stroop, 1935), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Heaton, 1980), Trail-making test (Corrigan, 1987), and Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-IV). All results were normalized for age using standardized procedures and converted to Z-scores. Participants that scored more than 2 standard deviations below the mean for memory, executive function, and attention were excluded from the study. No age differences emerged on the WAIS vocabulary sub-test (Wechsler, 1997). Subjective ratings of stress and health were also taken before completing the task, and no age differences emerged. Age, years of education, and scaled WAIS Vocabulary scores are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information.

| Mean Age | Vocabulary Z | Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face | Low Cognitive Load | Younger | 21.74 | 0.50 | 13.74 |

| Older | 66.87 | 1.41 | 17.70 | ||

| High Cognitive Load | Younger | 20.08 | 0.69 | 13.74 | |

| Older | 66.67 | 1.17 | 17.33 | ||

| Point | Low Cognitive Load | Younger | 21.88 | 0.43 | 13.84 |

| Older | 67.35 | 1.34 | 17.97 | ||

| High Cognitive Load | Younger | 20.55 | 0.99 | 13.83 | |

| Older | 66.74 | 1.33 | 18.48 | ||

*Vocabulary Z is the average Z score on the WAIS Vocabulary measure of intelligence. Education is years of education where a bachelors degree = 16 years.

Materials and Procedure

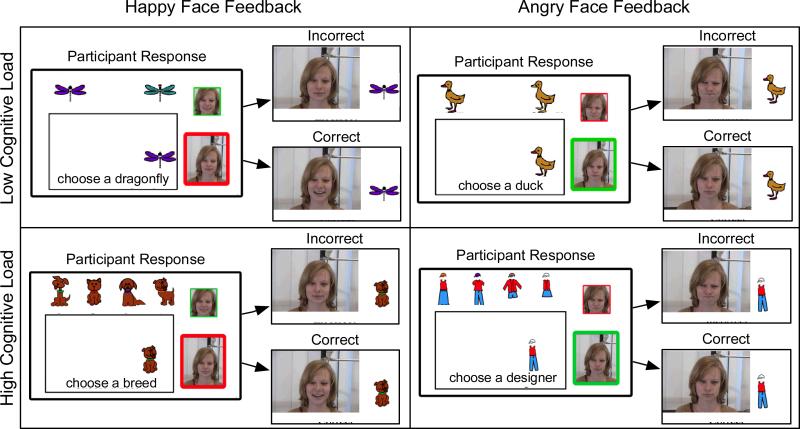

Participants in the low-cognitive-load condition completed a simple rule-learning task, with four stimuli constructed from a factorial combination of two binary-valued dimensions. On each of the 64 trials, participants were presented with one of the four stimuli and asked to categorize it into one of two categories. Unbeknownst to the participant, only one of the two stimulus dimensions was relevant to the categorization rule; along that dimension, each binary value was associated with one of the two categories. Participants were asked to pretend that they were ecologists, and that their task was to protect the environment by sorting cattails, frogs, ducks, or dragonflies into native and foreign species using trial-by-trial feedback (see upper panel of Figure 1). Different surface features were used for the happy-face-feedback and angry-face-feedback conditions, and were selected randomly from the four possible stimuli sets (cattails, frogs, ducks, or dragonflies). Once participants correctly categorized ten consecutive stimuli, the rule changed without their knowledge and the irrelevant dimension became relevant. Following the 64th trial, an exit screen provided information about whether the participant had reached their goal or not (defined below).

Figure 1.

Screen shots from the happy and angry-face-feedback conditions from the low cognitive load and the high-cognitive-load conditions.

Participants in the high-cognitive-load condition completed a complex rule-learning task with 64 stimuli constructed from the factorial combination of three stimulus dimensions, with four possible values for each dimension. On each of 128 trials, participants were presented with one of the 64 stimuli and asked to categorize it into one of four categories. Unbeknownst to the participant, only one of the three stimulus dimensions was relevant; along that dimension, each of the four possible values was associated with one of the four categories. Participants were either told that they had to sort dogs by breed or outfits by designer (see lower panel of Figure 1). Each participant was randomly assigned to a cover story (breed or designer) and a feedback condition (happy or angry). Once participants correctly categorized ten consecutive stimuli the rule changed (without their knowledge) and one of the two irrelevant dimensions was now relevant. Following the 128th trial, an exit screen provided information about whether the participant reached their goal or not (defined below).

Emotional face feedback was used in all conditions of Experiment 1. Participants in the low and high load conditions completed the task under happy-face-feedback conditions and under angry-face-feedback conditions. Task order (happy face vs. angry-face-feedback condition) was counterbalanced. On each trial in the happy-face-feedback condition, a correct response was followed by the presentation of a face with a large smile and an incorrect response was followed by a face with a small smile (see Figure 1 for examples). In the angry-face-feedback condition, a correct response was followed by the presentation of a face with a small frown and an incorrect response was followed by a face with a large frown (see Figure 1 for examples). In addition to trial by trial feedback, each condition had a global goal. This goal consisted of a face displayed on the right side of the screen that morphed from a neutral face to an emotional face. In the happy-face-feedback condition, the goal was to make the girl very happy. In the angry-face-feedback condition, the goal was to avoid making the girl very angry. The goal was attained if 80% of the responses were correct. The experiment was performed on PC computers using Flash software.

Results

In this section we examine three learning measures: overall accuracy, the number of trials needed to obtain 10 consecutive correct responses when learning the first rule (trials to first rule), and the number of trials needed to obtain 10 consecutive correct responses when learning the second rule (trials to second rule). Each measure taps into a different aspect of learning. Accuracy provides a global measure of learning, the number of trials to learn the first rule provides a measure of initial rule learning, and the number of trials to learn the second rule provides a measure of set shifting. Table 2 includes the means and standard errors for all conditions.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics for All Conditions

| Task Load | Feedback | Younger | Older | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy Rate | High | Happy Face | 0.83 (0.015) | 0.74 (0.016) |

| Angry Face | 0.78 (0.017) | 0.8 (0.017) | ||

| Point Gain | 0.84 (0.015) | 0.77 (0.015) | ||

| Point Loss | 0.84 (0.016) | 0.8 (0.016) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 0.86 (0.016) | 0.82 (0.017) | |

| Angry Face | 0.85 (0.017) | 0.8 (0.019) | ||

| Point Gain | 0.86 (0.014) | 0.83 (0.015) | ||

| Point Loss | 0.86 (0.015) | 0.81 (0.016) | ||

| Initial Rule Learning | High | Happy Face | 14.53 (1.78) | 24.83 (1.88) |

| Angry Face | 22.3 (2.44) | 20.89 (2.57) | ||

| Point Gain | 13.87 (1.74) | 21.07 (1.71) | ||

| Point Loss | 14.1 (1.89) | 22.03 (1.85) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 15.3 (1.85) | 15.67 (2.06) | |

| Angry Face | 14.22 (2.53) | 17.07 (2.81) | ||

| Point Gain | 13.44 (1.63) | 16.58 (1.71) | ||

| Point Loss | 15.32 (1.77) | 16.87 (1.85) | ||

| Set Shifting | High | Happy Face | 19.53 (2.42) | 26.58 (2.55) |

| Angry Face | 18.7 (2.05) | 16.03 (2.17) | ||

| Point Gain | 14.3 (1.62) | 17.48 (1.60) | ||

| Point Loss | 14.77 (2.07) | 19.07 (2.03) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 15.43 (2.52) | 23.4 (2.8) | |

| Angry Face | 18.6 (2.14) | 24.27 (2.37) | ||

| Point Gain | 17.03 (1.53) | 22.23 (1.6) | ||

| Point Loss | 16.53 (1.94) | 22.1 (2.03) |

*Standard errors in parentheses

Accuracy

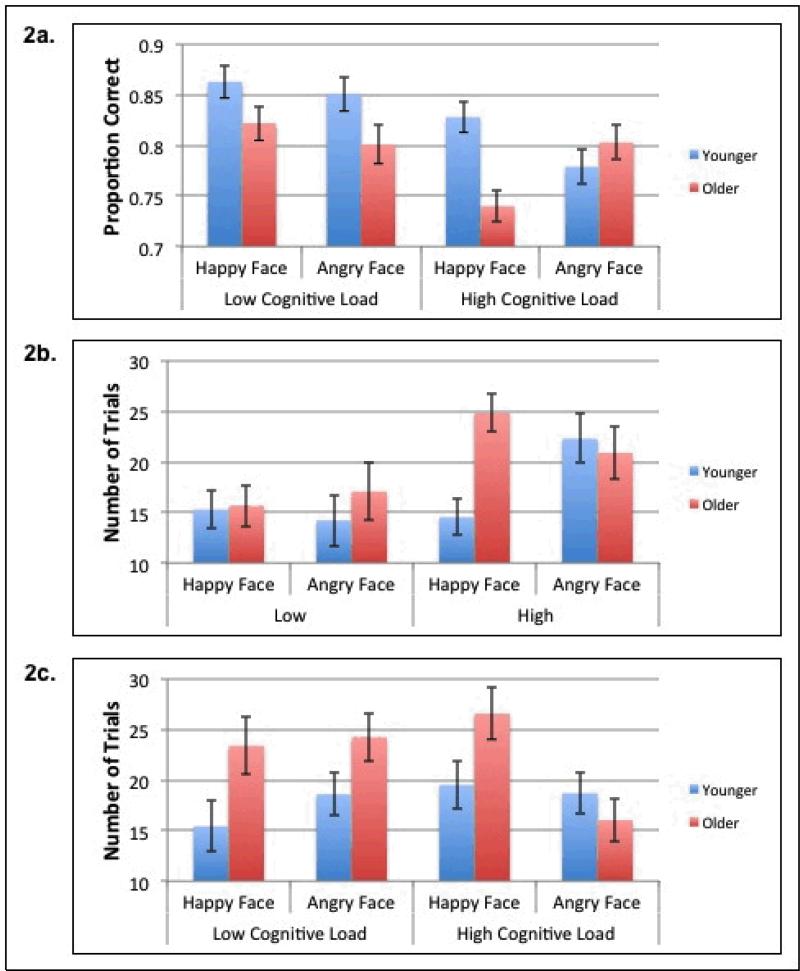

Overall accuracy was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 2a). There was a main effect of age, F(1,139)= 8.61, p=.004, η2=0.06, with younger adults performing more accurately than older adults (MOlder=.79, MYounger=.83), and a main effect of task load, F(1,139)= 12.37, p=.001, η2=0.08, with superior performance in the low cognitive load task relative to the high cognitive load task (MLow=.83, MHigh=.79). These effects were qualified by a significant three-way age × valence × cognitive load interaction, F(1,139)= 8.23, p=.004, η2=0.06, and no other significant effects.

Figure 2.

Experiment 1: a) Proportion correct for older and younger adults for the happy- and angry-face-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load, b) Number of trials to learn the first rule for older and younger adults for the happy- and angry-face-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load, c) Number of trials to learn the second rule for older and younger adults for the happy- and angry-face-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load. Standard error bars are included.

To decompose the three-way interaction, we conducted age × valence ANOVAs separately for the low- and high-cognitive-load conditions. In the low-cognitive-load condition, the only significant effect was a main effect of age, F(1,65)= 7.91, p=.007, η2=0.11, with younger adults performing more accurately than older adults (MOlder=.81, MYounger=.86). Although the interaction was not significant, we did predict a priori that the age-related learning deficit should be attenuated in the happy-face-feedback condition relative to the angry-face-feedback condition. The effect of age was significant for both happy t(65)= 2.34, p=0.02, and angry face feedback, t(65)= 2.23, p=0.03.

In the high-cognitive-load condition, there were no main effects of age or valence, but there was an age × valence interaction, F(1,74)= 11.93, p=.001, η2=0.14. Older adults performed as well as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition, t(74)= 0.89, p=0.38, ns, (MOlder=0.80, MYounger=0.78), but older adults performed significantly worse than younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition, t(74)= 3.44, p=.001, (MOlder=0.74, MYounger=.83). In addition, older adults were significantly more accurate with angry face feedback than with happy face feedback, t(35)= 2.77, p=.009, whereas younger adults were significantly less accurate with angry face feedback compared to happy face feedback, t(39)= 2.14, p=.04.

Trials to First Rule

The number of trials needed to learn the first rule was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 2b). There was a significant main effect of cognitive load, F(1,139)= 8.57, p=.004, η2=0.06, with participants taking longer to learn the first rule in the high-cognitive-load condition (MLow=15.6; MHigh=20.6). There were no main effects of age or valence and no two-way interactions, however, there was a significant age × valence × cognitive load interaction, F(1,139)= 5.84, p=.02, η2=0.04.

To decompose the three-way interaction we conducted age × valence ANOVAs separately for the low- and high-cognitive-load conditions. In the low-cognitive-load condition there were no main effects and no interaction. Again we examined age effects separately in the happy- and angry-face-feedback conditions because of our a priori predictions. Older adults performed as well as younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition, t(65)= 0.18, p=.86, ns, (MOlder=15.67, MYounger=15.30), but took marginally more trials than younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition, t(65)= 1.79, p=.08, ns, (MOlder=17.07, MYounger=14.22).

In the high-cognitive-load condition, there was no main effect of age or valence. However, there was a significant age × valence interaction, F(1,74)= 5.25, p=.03, η2=0.07. Older adults performed as well as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition, t(74)= 0.30, p=.76, ns, (MOlder= 20.9; MYounger=22.3) but older adults took significantly longer to learn the first rule than younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition, t(74)= 3.39, p=.001, (MOlder=24.8; MYounger=14.5). In addition, older adults showed no significant difference between the number of trials needed to learn the first rule given angry face feedback compared to happy face feedback, whereas younger adults took significantly more trials to learn the first rule given angry face feedback compared to happy face feedback, t(39)= -2.11, p=.04.

Trials to Second Rule

The number of trials needed to learn the second rule was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 2c). There was a significant main effect of age, F(1,139)= 6.54, p=.01, η2=0.05, with older adults taking more trials to learn the second rule than younger adults (MOlder=22.57; MYounger=18.06). A valence × cognitive load interaction, F(1,139)= 5.71, p=.02, η2=0.04 also emerged suggesting fewer trials are needed for second rule learning with happy face feedback in the low-cognitive-load condition, but fewer trials are needed for second rule learning with angry face feedback in the high-cognitive-load condition.

Although the three-way interaction was not significant, we decided to explore the pattern of age effects to provide some insights onto the nature of set shifting performance. Although potentially informative, these results should be interpreted with caution. In the low-cognitive-load condition, a significant age-deficit emerged in the happy-face-feedback condition, t(65)= 3.55, p=.001, (MOlder=23.40; MYounger=15.43), and in the angry-face-feedback condition, t(65)= 2.09, p=.04, (MOlder=24.27; MYounger=18.60).

On the other hand, a different pattern emerged in the high-cognitive-load condition. Older adults took marginally more trials than younger adults to learn the second rule in the happy-face-feedback condition, t(74)= 1.60, p=.11, ns, (MOlder=26.58; MYounger=19.53), and were as fast as younger adults to learn the second rule in the angry-face-feedback condition, t(74)= .80, p=.42, ns, (MOlder=16.03; MYounger=18.70).

Discussion

This study examined age-related changes in rule learning and set shifting as a function of the valence of highly emotional face feedback (happy vs. angry) in low and high cognitive load learning tasks. Previous research suggests that older adults use cognitive control resources to process positive emotional information more deeply than negative emotional information (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005; Petrican et al., 2008). However, when cognitive control resources are limited these effects can disappear or, at times, reverse. These biases likely influence the salience of feedback during learning. Thus, we predicted a systematic interaction between age, valence of the feedback and task cognitive load where happy face feedback to attenuates age-related learning deficits under low-cognitive-load conditions, and angry face feedback attenuates age-related learning deficits under high-cognitive-load conditions.

For the measures of initial and overall rule learning we found support for the predicted three-way interaction. Under low load conditions we predicted that happy face feedback would attenuate age-related deficits relative to angry face feedback. We found some support for this prediction in initial learning with no significant difference between younger adults and older adults in the number of trials needed to learn the first rule in the happy-face-feedback condition, and an age-deficit where older adults took 2.85 more trials than younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition. For overall learning, the age-related deficit was 4% in the happy-face-feedback condition and 5% in the angry-face-feedback condition yielding only a 1% difference across feedback conditions. Under high load conditions we predicted that angry face feedback would attenuate age-related deficits relative to happy face feedback. This prediction was supported. For initial learning we found no significant difference between younger adults and older adults in the number of trials needed to learn the first rule in the angry-face-feedback condition, however we found an age-related deficit where older adults took 10.30 more trials than younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition. Analogously, for overall learning, older adults were as accurate as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition and the age-related deficit was 9% in the happy-face-feedback condition. Thus, age-related deficits in initial and overall rule learning were attenuated when the cognitive load was high and angry face feedback was used.

Interestingly, the initial learning benefit observed for older adults in the low-cognitive-load condition with happy face feedback was attenuated significantly once the second rule was introduced and set shifting was required. In fact, the age-related set-shifting deficit was larger in the happy-face-feedback condition (7.97 trials) than in the angry-face-feedback condition (5.67 trials). Thus, it appears that the modest initial learning for older adults with happy face feedback came at the cost of reduced flexibility in processing making it more difficult to shift set.

However, in the high-cognitive-load condition older adults were as fast to shift set as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition (yielding a 2.67 trial set shifting advantage) whereas older adults were marginally slower to shift set than younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition (yielding a 7.05 trial set shifting deficit). Thus, the age-related performance advantage under high-cognitive-load conditions with angry face feedback was large and robust across all three measures of learning.

Although we predicted that the highly emotional nature of the face feedback is what led to the complex pattern of age-related deficits and performance advantages, it is possible that these effects also hold with less emotional feedback in the form of points gained and points lost. Experiment 2 addresses this possibility directly.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 revealed a systematic interaction between age, valence of the highly emotional face feedback, and cognitive load associated with solving the task. When task demands on cognitive control are low, happy face feedback attenuates deficits in overall learning, initial rule learning and, to a lesser extent, set shifting. However, during a complex task that places high demands on cognitive control, angry face feedback attenuates these age-related learning deficits. It is still unclear whether this complex three-way interaction generalizes to all valenced feedback or only applies to emotional face feedback.

One study comparing brain activation in younger adults receiving social face feedback vs. monetary feedback found that monetary feedback recruits a wide range of brain regions including the medial orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), striatum, superior frontal gyrus, medial temporal lobe, and insula (Lin et al., 2012). However, social feedback activated a smaller neural network mostly consisting of the medial orbitofrontal cortex. The OFC has been implicated in neural functions that are important for set shifting such as reversal learning (e.g., Fellows & Farah, 2003). Furthermore, recent research indicates that the OFC is more involved in updating emotional associations than non-emotional associations (Nashiro, Sakaki, Nga, & Mather, 2012; Sakaki, Niki, & Mather, 2011). This suggests that social and monetary feedback act through overlapping but separate neural networks, however it is unclear whether these differences affect set-shifting learning outcomes.

Another study suggests that monetary feedback in aging shows similar processing biases as those seen with face feedback. Samanez-Larkin and colleagues found that older and younger adults show similar patterns of brain activation while anticipating monetary gain, however older adults show less brain activation while anticipating monetary loss (Samanez-Larkin et al., 2007). While this study suggests that older adults are processing positive monetary feedback differently than negative monetary feedback, it is unclear if the anticipatory biases affect learning outcomes in older adults. Experiment 2 examines whether the performance interaction observed in Experiment 1 holds when highly emotional face feedback is replaced with less emotional point feedback.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-one older adults (Age: MOldLow= 67.35; RangeOldLow= 61-78) and 34 younger adults (Age: MYoungLow= 21.88; RangeYoungLow= 18-35) participated in the low cognitive load task and 31 older adults (Age: MOldHigh= 66.74; RangeOldHigh= 60-79) and 30 younger adults (Age: MYoungHigh= 20.55; RangeYoungHigh= 18-26) participated in the high cognitive load task for monetary compensation. Older adults were given the same battery of neuropsychological tests described in Experiment 1 and the same exclusion criteria were applied. In addition, younger and older adults were administered the WAIS vocabulary sub-test (Wechsler, 1997) and no age group differences emerged. Subjective ratings of stress and health were also taken before completing the task, and no age differences emerged.

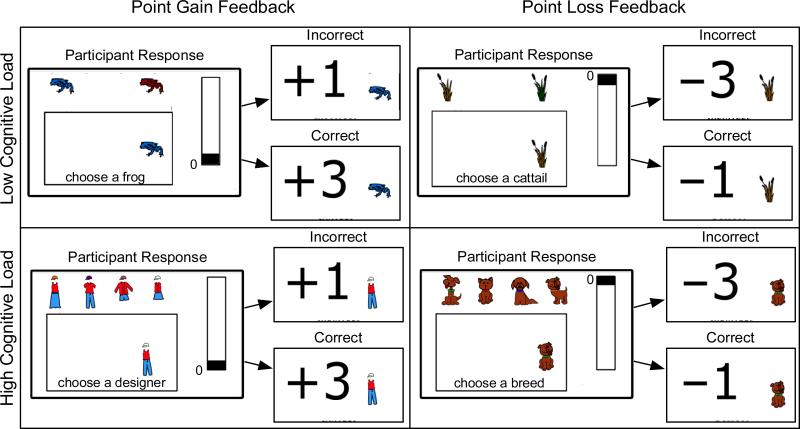

Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedures were identical to Experiment 1, except that highly emotionally face feedback was replaced with less emotional point feedback (see Figure 3). In the “point gain” feedback condition, a correct response was followed by a display of +3 points and an incorrect response was followed by a display of +1 point. In the point-loss-feedback condition, a correct response was followed by a display of -1 point and an incorrect response was followed by a display of -3 points. In the point-gain- feedback condition, the goal was to fill the point meter to the top, whereas in the point-loss-feedback condition, the goal was to avoid letting the point meter drop to the bottom. Their goal was attained if participants achieved 80% accuracy. As in Experiment 1, task order was counterbalanced and surface features were randomly assigned. The experiment was performed on PC computers using Flash software.

Figure 3.

Screen shots from the point-gain- and point-loss-feedback conditions from the low-cognitive-load and high-cognitive-load conditions.

Results

Following the procedures outlined in Experiment 1, we examined overall accuracy, trials to learn the first rule, and trials to learn the second rule.

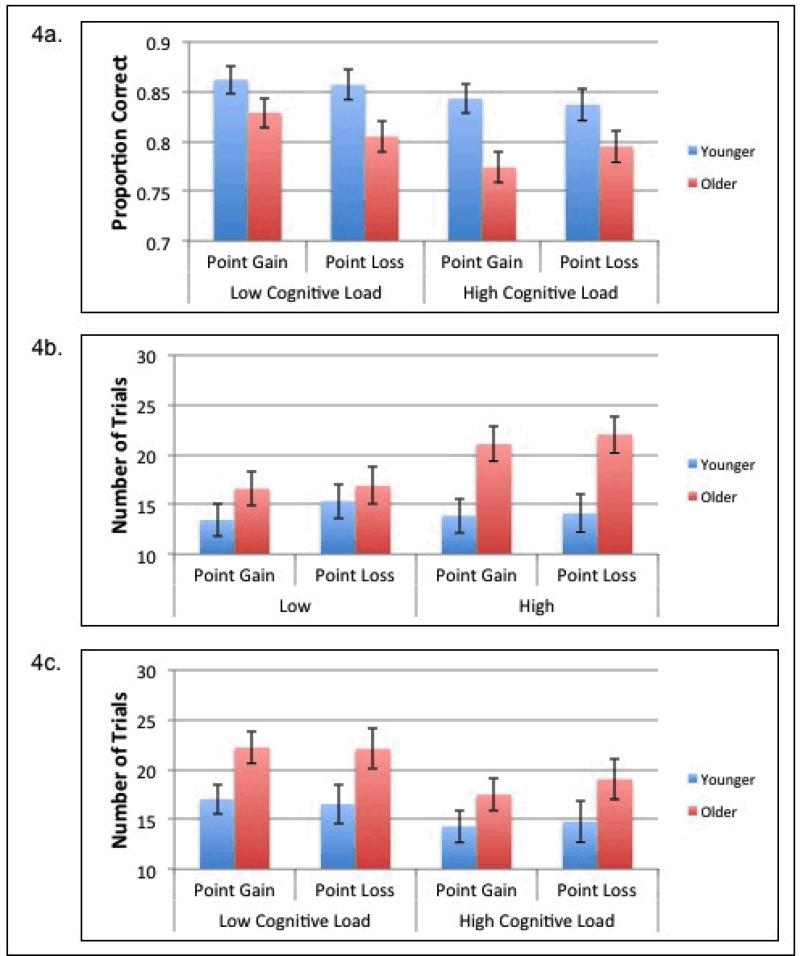

Accuracy

Overall accuracy was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 4a). There was a significant main effect of age, F(1,122)= 15.71, p<.001, η2=0.11, with older adults performing worse than younger adults (MOlder=.80; MYounger=.85), and a significant main effect of cognitive load, F(1,122)= 4.35, p=.04, η2=0.03, with participants being more accurate in the low-cognitive-load condition than in the high-cognitive-load condition (MLow=.84; MHigh=.81). No other effects reached significance.

Figure 4.

Experiment 2: a) Proportion correct for older and younger adults for the point-gain- and point-loss-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load, b) Number of trials to learn the first rule for older and younger adults for the point-gain- and point-loss-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load, c) Number of trials to learn the second rule for older and younger adults for the point-gain- and point-loss-feedback conditions under low cognitive load and high cognitive load. Standard error bars are included.

Trials to First Rule

The number of trials needed to learn the first rule was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 4b). There was a significant main effect of age, F(1,122)= 17.74, p<.001, η2=0.13,with older adults taking more trials to learn the first rule than younger adults (MOlder=19.1; MYounger=14.2). No other effects reached significance.

Trials to Second Rule

The number of trials needed to learn the second rule was calculated for each participant and a 2 (age) × 2 (valence) × 2 (cognitive load) mixed ANOVA was conducted (see Figure 4c). There was a significant main effect of age, F(1,122)= 12.98, p<.001, η2=0.1, with older adults taking more trials to learn the second rule than younger adults (MOlder=20.2; MYounger=15.7), and a significant main effect of cognitive load, F(1,122)= 5.87, p=.02, η2=0.05, with participants taking more trials to learn the second rule in the high-cognitive-load condition than in the low-cognitive-load condition (Mlow=19.5; Mhigh=16.4). No other effects reached significance.

Discussion

This study repeated the format of Experiment 1, but replaced emotional face feedback with less emotional point feedback. Older adults showed the learning deficits classically seen in set shifting paradigms. Older adults were less accurate, needed more trials to learn the initial rule, and needed more trials to learn the second rule relative to younger adults. This pattern contrasts with the three-way age × valence × cognitive load interaction observed in Experiment 1 where highly emotional stimuli attenuated learning deficits. The results from Experiment 2 are important because they demonstrate that the valence manipulation (positive feedback vs. negative feedback) in isolation is not sufficient to attenuate age-related deficits. Successful learning depends on the emotional content of the feedback (happy faces vs. angry faces) and age-related deficits are still seen with less emotional feedback (point gain vs. point loss).

General Discussion

The overriding aim of this study was to see if well-established rule learning and set-shifting deficits observed in normal aging could be attenuated by incorporating highly emotional faces as feedback. Previous research suggests that the processing of emotional information is enhanced in older adults, but that the valence of enhanced information changes as a function of the cognitive control resources available for processing (Kryla-Lighthall & Mather, 2009). When cognitive control resources are readily available, positive emotional information is processed more deeply, whereas when cognitive control resources are less readily available, negative emotional information is processed more deeply (Knight et al., 2007). In addition, older adults need good cognitive control to prevent mood declines through gaze preferences for happy faces and away from angry faces (Isaacowitz et al., 2009). We hypothesized that if highly emotional information in the form of happy faces or angry faces was used as feedback, enhanced processing of emotional information might be exploited to bootstrap learning in older adults. We predicted that happy face feedback would attenuate age-related learning deficits when the task placed minimal load on cognitive control resources, whereas angry face feedback would attenuate age-related learning deficits when the task placed a high load on cognitive-control resources.

The results from Experiment 1 supported our predictions. Under low-cognitive-load conditions older adults performed as well as younger adults in the happy-face-feedback condition and showed a large initial rule learning deficit in the angry-face-feedback condition. This pattern showed a significant reversal under high-cognitive-load conditions where older adults performed as well as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition, but showed a large initial rule-learning deficit in the happy-face-feedback condition. Unfortunately, any benefit in initial rule learning that older adults enjoyed with happy face feedback under low-cognitive-load conditions came at a cost in reduced flexibility once the rule switched. Specifically, under low-cognitive-load conditions older adults showed a large set-shifting deficit relative to younger adults in both the happy face and angry-face-feedback conditions. On the other hand, the benefit in initial rule learning that older adults enjoyed with angry face feedback under high-cognitive-load conditions was also present once the rule switched. Specifically, under high-cognitive-load conditions older adults performed as well as younger adults in the angry-face-feedback condition, despite the presence of a modest set-shifting deficit in the happy-face-feedback condition.

Experiment 2 repeated Experiment 1's procedure with the highly emotional face feedback replaced by less emotional point feedback. We predicted that point feedback would not be processed more deeply by older adults than younger adults and thus would yield across-the-board age-related deficits. As predicted, age-related deficits emerged for the low and high-cognitive-load conditions when the feedback came in the form of points gained or points lost.

Taken together, these data suggest that age-related rule learning deficits are more flexible then once thought. These deficits can be attenuated if the appropriate feedback is paired with the task demands on cognitive load to optimize the speed of initial learning and the flexibility needed to efficiently shift set. The current study suggests that angry face feedback optimizes rule learning when the task is complex and places a strong demand on cognitive control resources, whereas happy face feedback optimizes rule learning when the task is simpler and places less demand on cognitive control resources.

Nashiro and colleagues (Nashiro et al., 2011) examined the differential effects of happy and angry face feedback on older and younger adults’ learning in a task with low cognitive load that required initial rule learning and rule switching. As predicted, older adults made more errors in the angry-face-feedback condition than younger adults, but this deficit was attenuated with happy face feedback. Importantly, Nashiro et al. only examined an overall measure of performance, the number of errors made across the task, which obscures differential learning effects across phases of learning. The present study helps fill this critical gap in our understanding of the effects of age and feedback on initial learning and set shifting. Data from the current study suggests that the attenuated age deficit for happy face feedback in Nashiro et al. is most likely due to effects on initial learning and not on set shifting. Future work should explore this more fully.

Rule Learning and Set Shifting

In the current study we found an interesting dissociation between initial rule learning and set shifting for older and younger adults, under low and high-cognitive-load conditions. Under low-cognitive-load conditions, we found that the age-related initial rule-learning deficit tended to be attenuated with happy face feedback, but that this came at a cost of even larger set-shifting deficits. On the other hand, under high-cognitive-load conditions, we found that the age-related initial rule-learning and set-shifting deficits were attenuated with angry face feedback.

The nature of the feedback may be partially responsible for the dissociation between initial rule learning and set shifting. Error feedback is critical when determining if a strategy is not working and a rule shift is needed. In the happy face condition, errors are presented as a small smile and in the angry face condition errors are presented as a large frown. This may make angry face errors easier to interpret because the change in emotion is larger and the emotional component of the feedback (negative) aligns with the feedback (error). This asymmetry in the emotional component with feedback would not affect initial rule learning as drastically, because both correct and error feedback can be used to maintain rules.

In the low-cognitive-load condition, older adults process happy face feedback more deeply than angry face feedback. This helps initial rule learning where large smiles are used to guide selection of the first rule; however, small smiles indicating errors are not salient enough to elicit a rule shift. Angry face feedback is ineffective in both initial rule learning and set shifting because it is processed shallowly. In the high-cognitive-load condition, negative feedback is processed more deeply than positive feedback. Happy face feedback is ineffective in both initial rule learning and set shifting because it is processed more shallowly. Angry face feedback is processed more deeply, which allows older adults to learn the initial rule and determine when to shift set through errors indicated with large frowns. This explanation is admittedly speculative but deserves further investigation.

Individual Differences

Given the importance of the cognitive load manipulation in the current findings, it is worth exploring the possibility that individual differences in executive functioning across older adults might affect the pattern of results. Previous research suggests that older adults’ executive function interacts with emotional processing (Isaacowitz et al., 2009; Mather & Knight, 2005; Petrican et al., 2008). Because of our relatively small sample sizes and the fact that we did not collect measures of executive function in our younger adult sample, we deem these analyses exploratory. Even so, some interesting patterns emerged. We utilized the popular Stroop interference measure as our measure of executive function (Stroop, 1935). We performed a median-split on Stroop interference z-scores and classified older adults as high or low on executive functioning. Performance means for each condition are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary statistics for older adults grouped by poor or good executive function (EF) measured using the Stroop task.

| Task Load | Feedback | Older Good EF | Older Poor EF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy Rate | High | Happy Face | 0.78 (0.02) | 0.69 (0.02) |

| Angry Face | 0.82 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.03) | ||

| Point Gain | 0.8 (0.02) | 0.76 (0.02) | ||

| Point Loss | 0.8 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.02) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 0.84 (0.02) | 0.8 (0.03) | |

| Angry Face | 0.81 (0.03) | 0.79 (0.03) | ||

| Point Gain | 0.83 (0.02) | 0.83 (0.02) | ||

| Point Loss | 0.82 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.02) | ||

| Initial Rule Learning | High | Happy Face | 24.3 (2.53) | 25.5 (2.83) |

| Angry Face | 21.3 (3.47) | 20.38 (3.88) | ||

| Point Gain | 22.92 (2.66) | 19.72 (2.26) | ||

| Point Loss | 22.23 (2.87) | 21.89 (2.44) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 14.5 (2.83) | 17 (3.03) | |

| Angry Face | 16.81 (3.88) | 17.36 (4.15) | ||

| Point Gain | 16.31 (2.39) | 16.87 (2.47) | ||

| Point Loss | 18.81 (2.59) | 14.8 (2.67) | ||

| Set Shifting | High | Happy Face | 19.15 (3.28) | 35.88 (3.67) |

| Angry Face | 13.95 (2.90) | 18.63 (3.25) | ||

| Point Gain | 15 (2.46) | 19.28 (2.09) | ||

| Point Loss | 16 (3.13) | 21.28 (2.66) | ||

| Low | Happy Face | 19.25 (3.67) | 28.14 (3.92) | |

| Angry Face | 22 (3.25) | 26.86 (3.47) | ||

| Point Gain | 20.56 (2.22) | 24 (2.29) | ||

| Point Loss | 20.5 (2.83) | 23.8 (2.92) |

*Standard errors in parentheses

Experiment 1 utilized highly emotional face feedback to attenuate learning differences. An examination of Table 3 suggests that when executive function is good and the cognitive load is low, happy face feedback may attenuate the age-related initial rule-learning deficit. However, under high-cognitive-load conditions, good executive function had little effect on initial rule learning. With respect to set shifting, high functioning older adults showed faster set shifting than low functioning older adults in all four conditions. Experiment 2 utilized less emotional point feedback and the results were more straightforward. As suggested by an examination of Table 3, in general, high functioning older adults showed faster initial rule learning and set shifting than low functioning older adults, but high functioning older adults never performed at an equivalent or better level than younger adults.

Taken together these data suggest that good executive function plays a different role in positive versus negative emotional information processing. In the low-load condition, those with good executive function show emotional biases where happy face feedback leads to age-related advantages in initial rule formation, as well as an attenuation of the set-shifting deficit. However, older adults with poor executive function are worse than younger adults in initial rule formation and set shifting across valence. We do not see this interaction in the high-cognitive-load condition where negative emotional information is more salient. Here, older adults show performance advantages given angry face feedback regardless of their level of executive function. This suggests that emotional biases for positive emotional feedback are driven by executive processes but negative emotional feedback is not.

Limitations

Although the results presented in this study are compelling, there are a number of limitations that are worth noting. First, given the importance of cognitive-control demands and resources in the present work, a more detailed examination of individual differences in cognitive control processing and resources is in order. The preliminary analyses presented above are suggestive, but a larger sample size is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn. In addition, though the Stroop task taps executive function it also relies on attentional resources. It would be informative for future work to look for convergent evidence across several measures of executive function. Second, measures of affect and mood should be included in future work. We collected subjective ratings of stress and health and found no age differences. Even so, affect and mood may have differed across age groups and conditions. Although it is difficult to imagine how these might account for the systematic interaction observed in the present study, these measures might still be informative. In fact, it would be interesting to see how the different feedback conditions change affect and mood throughout the course of learning. These ratings could provide insights as to whether these effects are due to age differences in emotion regulation strategies or differences in the processing of emotional information (Isaacowitz & Blanchard-Fields, 2012). Finally, while the current study provides important insights into the way that emotionally-valenced feedback affects age-related differences in rule learning, it provides no insights into other forms of learning. Contemporary cognitive theory emphasizes (at least) two systems that underlie learning: a reflective system where processing is frontally-mediated and under conscious control, and a reflexive system where processing is striatally-mediated and not under conscious control (Ashby & Maddox, 2005; Ashby, Alfonso-Reese, Turken, & Waldron, 1998). The current study focuses on reflective (frontally-mediated rule) learning. It is known that cognitive load differentially affects performance in the two learning systems (Filoteo, Lauritzen, & Maddox, 2010), but it is unclear how highly emotional face feedback might affect learning in the striatal system. Future research should explore these effects.

Conclusions

This study reports the results from two experiments that examined the effects of highly emotional face feedback on in initial rule learning and set shifting using tasks that involve a low or a high cognitive load. When the task placed minimal load on cognitive control resources, we found that happy face feedback tended to attenuate age-related initial rule learning deficit, but that this advantage came with a cost once the rule switched. Under the same cognitive load conditions, we also found that angry face feedback led to large age-related initial rule learning and set shifting deficits. However, when the task placed a heavy load on cognitive control resources, we found that angry face feedback attenuated an age-related deficits in initial rule learning and set shifting, whereas happy face feedback led to age-related initial rule-learning and set-shifting deficits. When the highly emotional face feedback was replaced with less emotional point feedback, we found age-related performance deficits across the board.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant R01 MH077708 and NIDA grant DA032457 to WTM and a University of Texas Diversity Fellowship to MAG. We thank Taylor Denny for her help with data collection.

Appendix

Methods and Results From Small-Scale Pilot Study

Participants

Four older and four younger adults completed the pilot study. Older adults completed the same neuropsychological test battery used in Experiments 1 and 2 and met the same inclusion criterion.

Procedure

Each participant completed 12 trials in each of four feedback conditions (happy face, angry face, point gain, and point loss) from the low cognitive load task. Following presentation of the feedback on each trial, participants were asked to rate the emotionality of the feedback on a scale from 1 to 5 where 1 denotes low emotionality and 5 denotes high emotionality. Four condition orders were used with one older and one younger adult completing the task in each of the following condition orders: happy-angry-gain-loss, angry-happy-loss-gain, gain-loss-happy-angry, and loss-gain-angry-happy.

Results

Average emotionality ratings were computed for face and point feedback separately for each participant. Face feedback was rated as significantly more emotional than point feedback (t(7) = 3.35, p = .012) with average emotionality ratings of 3.37 and 2.76 for face and point feedback, respectively. For younger adults, the average emotionality ratings were 3.45 and 2.57 for face and point feedback, respectively. For older adults the average emotionality ratings were 3.30 and 2.95 for face and point feedback, respectively. Thus, face feedback is rated as more emotionally salient than point feedback for both older and younger adults.

References

- Anderson AK, Christoff K, Panitz D, De Rosa E, Gabrieli JDE. Neural correlates of the automatic processing of threat facial signals. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(13):5627–5633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05627.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Alfonso-Reese LA, Turken U, Waldron EM. A neuropsychological theory of multiple systems in category learning. Psychological Review. 1998;105:442–481. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Maddox WT. Human category learning. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56(1):149–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Barch DM. A theory of cognitive control, aging cognition, and neuromodulation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26(7):809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(4):644–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology General. 2003;132(2):310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JDH, M. S. Relationships between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1987;43:402–409. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198707)43:4<402::aid-jclp2270430411>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows LK, Farah MJ. Ventromedial frontal cortex mediates affective shifting in humans: evidence from a reversal learning paradigm. Brain. 2003;126(8):1830–1837. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filoteo JV, Lauritzen S, Maddox WT. Removing the frontal lobes. Psychological Science. 2010:415–423. doi: 10.1177/0956797610362646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, Hongwanishkul D, Keightley M, Lee W, Hasher L. The effect of age on memory for emotional faces. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(3):371–380. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grühn D, Scheibe S, Baltes PB. Reduced negativity effect in older adults’ memory for emotional pictures: The heterogeneity-homogeneity list paradigm. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22(3):644–649. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Raz N. Neuroanatomical correlates of selected executive functions in middle-aged and older adults: a prospective MRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(14):1929–1941. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head D, Kennedy KM, Rodrigue KM, Raz N. Age differences in perseveration: cognitive and neuroanatomical mediators of performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(4):1200–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK. A manual for the Wisconsin card sorting test. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Odessa, Florida: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Blanchard-Fields F. Linking process and outcome in the study of emotion and aging. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7(1):3–17. doi: 10.1177/1745691611424750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM. Motivated gaze: the view from the gazer. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(2):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Neupert SD. Use of gaze for real-time mood regulation: effects of age and attentional functioning. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(4):989–994. doi: 10.1037/a0017706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Q, Mather M, Carstensen LL. The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical memory. Psychological Science. 2004;15(3):208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.01503011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Seymour TL, Gaunt JT, Baker C, Nesmith K, Mather M. Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion. 2007;7(4):705–714. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobau R, Safran MA, Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Chapman D. Sad, blue, or depressed days, health behaviors and health-related quality of life, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1995-2000. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2(40) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryla-Lighthall N, Mather M. Handbook of Theories of Aging. 2nd Edition Springer Publishing; 2009. The role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional well-being. pp. 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc CM, Kensinger EA. Effects of age on detection of emotional information. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(1):209–215. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Adolphs R, Rangel A. Social and monetary reward learning engage overlapping neural substrates. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7(3):274–281. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson SE, Phillips LH, Sala SD. Age, executive function, and social decision making: A dorsolateral prefrontal theory of cognitive aging. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(4):598–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox WT, Pacheco J, Reeves M, Zhu B, Schnyer DM. Rule-based and information-integration category learning in normal aging. Neuropsychologia. 2010:2998–3008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(10):496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-directed memory: the role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional memory. Psychology Aging. 2005;20(4):554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M, McCaffrey M. The allure of the alignable: younger and older adults’ false memories of choice features. Journal of Experimental Psychology General. 2005;134(1):38–51. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science. 2003;14(5):409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. The emotion paradox in the aging brain. Annals of the New York Acadamy of Sciences. 2012;1251(1):33–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchi O, Petrides M, Petre V, Worsley K, Dagher A. Wisconsin Card Sorting revisited: distinct neural circuits participating in different stages of the task identified by event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(19):7733–7741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07733.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy NA, Isaacowitz DM. Preferences for emotional information in older and younger adults: A meta-analysis of memory and attention tasks. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(2):263–286. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashiro K, Sakaki M, Mather M. Age differences in brain activity during emotion processing: Reflections of age-related decline or increased emotion regulation? Gerontology. 2012;58(2):156–163. doi: 10.1159/000328465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashiro K, Sakaki M, Nga L, Mather M. Differential brain activity during emotional vs. non-emotional reversal learning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;24:1794–1805. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashiro K, Mather M, Gorlick MA, Nga L. Negative emotional outcomes impair older adults’ reversal learning. Cognition and Emotion. 2011;124(3):301–312. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.542999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Ray RD, Cooper JC, Robertson ER, Chopra S, Gabrieli JDE, Gross JJ. For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down-and up-regulation of negative emotion. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cognitive Science. 2005;9(5):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Flykt A, Esteves F. Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130(3):466–478. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgeta V. Avoiding threat in late adulthood: testing two life span theories of emotion. Experimental Aging Research. 2011;37(4):449–472. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2011.590759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, Smith PK. Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(2):299–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrican R, Moscovitch M, Schimmack U. Cognitive resources, valence, and memory retrieval of emotional events in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(3):585–594. doi: 10.1037/a0013176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(9):833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine CA, Barch DM, Braver TS, Noelle DC. The effect of age on rule-based category learning. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2006;13(3):411–434. doi: 10.1080/13825580600574377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki M, Niki K, Mather M. Updating existing emotional memories involves the frontopolar/orbitofrontal cortex in ways that acquiring new emotional memories does not. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:3498–3514. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(4):140–144. doi: 10.1177/0963721414535212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Gibbs SEB, Khanna K, Nielsen L, Carstensen LL, Knutson B. Anticipation of monetary gain but not loss in healthy older adults. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(6):787–791. doi: 10.1038/nn1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. Intellectual Development in Adulthood. pp. 266–286. [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;28:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P. Aging and executive control: reports of a demise greatly exaggerated. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20(3):174–180. doi: 10.1177/0963721411408772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Cerella J. Aging, executive control, and attention: A review of meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26(7):849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Steitz DW, Sliwinski MJ, Cerella J. Aging and dual-task performance: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(3):443–460. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III: Administration and Scoring Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Psychological Corporation San Antonio; TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]