Abstract

Many Vibrio anguillarum serotype O1 strains carry 65-kb pJM1-type plasmids harboring genes involved in siderophore anguibactin biosynthesis and transport. The anguibactin system is an essential factor for V. anguillarum to survive under iron-limiting conditions, and as a consequence, it is a very important virulence factor of this bacterium. Our comparative analysis of genomic data identified a cluster harboring homologs of anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes in the chromosome of Vibrio harveyi. We have purified the putative anguibactin siderophore and demonstrated that it is indeed anguibactin by mass spectrometry and specific bioassays. Furthermore, we characterized two genes, angR and fatA, in this chromosome cluster that, respectively, participate in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport as determined by mutagenesis analysis. Furthermore, we found that the V. harveyi FatA protein is located in the outer membrane fractions as previously demonstrated in V. anguillarum. Based on our data, we propose that the anguibactin biosynthesis and transport cluster in the V. anguillarum pJM1 plasmid have likely evolved from the chromosome cluster of V. harveyi or vice versa.

Keywords: Anguibactin, iron transport, siderophore, Vibrio anguillarum, Vibrio harveyi

Introduction

Iron is an essential element for nearly all living organisms as it is involved in many metabolic processes; however, the amount of free iron in the environment as well as in the host is very limited due to its insolubility at neutral pH in the presence of oxygen and chelation by high-affinity iron-binding host products. To overcome these iron-limiting conditions, bacteria express high-affinity iron acquisition systems. One of them is siderophore-mediated iron transport system. Bacteria biosynthesize and secrete siderophores that chelate ferric iron and the ferric-siderophore complex are then taken up into the bacterial cytosol via specific outer membrane receptors and ATPase-dependent ABC transporters or proton motive force–dependent permeases (Crosa and Walsh 2002; Cuiv et al. 2004; Raymond and Dertz 2004; Winkelmann 2004; Hannauer et al. 2010; Reimmann 2012).

Vibrio anguillarum is a marine pathogen that causes serious hemorrhagic septicemia in wild and cultured fish (Actis et al. 2011; Naka and Crosa 2011). Many V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains produce the siderophore anguibactin and take up ferric-anguibactin via the cognate outer membrane receptor FatA (Actis et al. 2011; Naka and Crosa 2011). The anguibactin-mediated system is an essential factor for the multiplication of this bacterium under iron-limiting conditions, and it is the most important virulence factor of this fish pathogen (Crosa 1980; Actis et al. 2011; Naka and Crosa 2011). The majority of genes involved in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport are encoded in the 65-kb pJM1 or pJM1-like plasmids of V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains (Crosa and Walsh 2002; Di Lorenzo et al. 2003; Actis et al. 2011). On the other hand, many natural pJM1-less O1 serotype strains and other serotype strains produce and transport the chromosomally-mediated siderophore vanchrobactin (Balado et al. 2006, 2008, 2009; Soengas et al. 2006). It has been reported that V. anguillarum serotype O1 strain carrying the pJM1-type plasmid always produces only anguibactin but not vanchrobactin (Lemos et al. 1988). Our previous work unveiled that V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) does not produce vanchrobactin due to the interruption of the vabF vanchrobactin biosynthesis gene by a transposon found in the pJM1 plasmid. Removal of the transposon caused the recovery of the vanchrobactin production (Naka et al. 2008) in an isogenic V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) derivative. However, vanchrobactin activity was not detected from the strain that produces both anguibactin and vanchrobactin due to the competition for iron between two siderophores as anguibactin has higher iron affinity than vanchrobactin (Naka et al. 2008). Furthermore, the interruption of the vabF gene by the transposon was commonly found in the pJM1-carrying strains isolated from different geographical origins (Naka et al. 2008). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the iron uptake phenotype of V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) may have evolved from an ancestor that acquired the pJM1-encoded anguibactin-mediated system. This system could have a higher iron affinity than the vanchrobactin-mediated system encoded in the ancestor's chromosome (Naka et al. 2008). Although the anguibactin system has been extensively studied by our group, the cluster carrying anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes has been only identified on the pJM1-type plasmid in V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains.

In this study, we show that an anguibactin gene cluster similar to that described in the V. anguillarum pJM1 plasmid is located on the chromosome of Vibrio harveyi. This organism is a marine bioluminescent bacterium ubiquitously found in seawater, mainly in the tropical regions, that is a pathogen of many marine vertebrate and invertebrate species (Thompson et al. 2004; Austin and Zhang 2006; Owens and Busico-Salcedo 2006). We also demonstrate that V. harveyi HY01 angR and fatA orthologs are essential for anguibactin biosynthesis and uptake, respectively. Our results suggest a possible evolutionary origin of the anguibactin system in these two Vibrio species strains.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Primers used in this study are shown in Table S1. Although some strains are proposed to change species name from V. harveyi to Vibrio campbellii or vice versa based on increasing genomic data, we decide to keep the original designation pending official taxonomic revision.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains and plasmids | Characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio anguillarum strains | ||

| 775 (pJM1) | Wild type, Washington (serotype O1, pJM1) | Crosa (1980) |

| 775 (pJM1)-pMMB | 775 (pJM1) harboring pMMB208 | Naka et al. (2008) |

| 96F-pMMB | Vanchrobactin producer (serotype O1, plasmidless) harboring pMMB208 | Naka et al. (2008) |

| HNVA-8 | CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA (anguibactin indicator strain) | Naka and Crosa (2012) |

| Vibrio harveyi strains | ||

| ATCC BAA-1116 | Marine (Ocean) isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| HY01 | Dead, luminescing shrimp isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| HNVH-1 | HY01ΔangR | This study |

| HNVH-2 | HY01ΔangRΔfatA | This study |

| CAIM 148 | Diseased shrimp (Penaeus sp.) hemolymph isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 513T | Dead, luminescing amphipod (Talorchestia sp.) isolate V. harveyi type strain ATCC 14126 | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 1075 | Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 1766 | Sea horse (Hippocampus ingens) liver isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 1792 | Diseased shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) lesion isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| Vibrio campbellii strains | ||

| 42A | Healthy coral (Mussismilia hispida) isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 115 | Shrimp (Litopenaeus sp.) hemolymph isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 198 | Shrimp (Litopenaeus sp.) hepatopancreas isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 519T | Seawater isolate V. campbellii type strain ATCC 25920 | Lin et al. (2010) |

| CAIM 1500 | Snapper (Lutjanus guttatus) liver isolate | Lin et al. (2010) |

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F−, ϕ80lacZΔM15, endA1, recA1, hsdR17, (rK−mK+), supE44, thi-1, gyrA96, relA1, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, λ− | Laboratory stock |

| S17-1λpir | λ-pir lysogen; thi pro hsdR hsdM+recA RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 (Tpr Smr) | Simon et al. (1983) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | A vector for the cloning of PCR products with blue/white screening, Apr | Promega |

| pBluescript II | Cloning vector, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pBluescript-Km | Cloning vector, Kmr | This study |

| pDM4 | Suicide plasmid sacB gene, R6K origin, Cmr | Milton et al. (1996) |

| pHN11 | pDM4 harboring ΔangR of V. harveyi HY01 | This study |

| pHN12 | pDM4 harboring ΔfatA of V. harveyi HY01 | This study |

| pMMB208 | A broad-host-range expression vector; Cmr IncQ lacIq Ptac; polylinker from M 13mp19 | Morales et al. (1991) |

| pHN13 | pMMB208 harboring V. harveyi angR | This study |

| pHN14 | pMMB208 harboring V. harveyi fatA | This study |

ATCC and CAIM strains were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (http://www.atcc.org) and Collection of Aquatic Important Microorganisms (http://www.ciad.mx/caim), respectively.

Vibrio harveyi strains were grown in Luria Marine (LM) medium containing LB broth (Difco, Sparks, MD) and 1.5% NaCl or in AB medium (Taga and Xavier 2011) at 30°C. Thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar (Difco) was used as a selective medium for V. harveyi to counterselect Escherichia coli. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in LB broth or LB agar (LB broth supplemented with 1.5% agar) at 37°C. When needed, antibiotics were added to the medium in the following concentrations: for V. harveyi or V. anguillarum, chloramphenicol (Cm) 10 μg/mL; for E. coli, ampicillin 100 μg/mL, Cm 30 μg/mL.

Generation of mutants and complementation

To construct ΔangR in V. harveyi HY01, the upstream and downstream regions of the target genes were PCR amplified using HY01angR–mut-up-SalI-F and HY01angR–mut-up-SmaI-R, and HY01angR–mut-down-SmaI-F and HY01angR–mut-down-SpeI R primers, respectively. Both fragments were independently cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector and subsequently subcloned into pBluescript-Km using restriction enzymes that recognize the recognition sites added in both ends of the primers. pBluescript-Km was generated by inserting the Km resistance DNA fragment obtained by SmaI digestion of pBlue-Km-SmaI (Naka et al. 2012) into the ScaI site of pBluescript II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). To construct the ΔangRΔfatA double mutant in V. harveyi HY01, the PCR-amplified DNA fragments obtained using HY01angRfatA–mut-up-XhoI-F and HY01angRfatA–mut-up-SmaI-R primers were cloned into pGEM-T Easy and subsequently subcloned into pBluescript-Km together with the DNA fragment obtained using HY01angR–mut-down-SmaI-F and HY01angR–mut-down-SpeI-R.

The deletion fragments were subcloned into the suicide vector pDM4 (Milton et al. 1996) and the plasmids were maintained into E. coli S17-1 λ pir. The pDM4 derivatives thus constructed were conjugated into V. harveyi strains, selecting the exconjugants on TCBS plus Cm. Selected exconjugants were plated on LM plates containing 20% sucrose to isolate the proper V. harveyi deletion derivatives, which were screened by colony PCR using primers constructed outside (HY01angR–mut-up-SalI-F and HY01angR–mut-down-SpeI R to check ΔangR and HY01angRfatA–mut-up-XhoI-F and HY01angR–mut-down-SpeI R to check ΔangRfatA) and inside (HY01angR-inter-F and HY01angR-inter-R to check ΔangR and HY01fatA-inter-F and HY01fatA-inter-R to check ΔfatA) of the target genes. The size of the PCR fragments obtained from the mutants using external primers was shorter than those from the wild type, and we did not observe any PCR products when internal primers were used for colony PCR in the mutants, while the wild-type positive control showed clear PCR products (data not shown).

To complement the mutants, the wild-type genes including their Shine–Dalgarno sequences were PCR amplified using primers containing restriction enzyme sites such as HY01angR-com-PstI-F and HY01angR-com-EcoRI to complement ΔangR, and HY01fatA-com-SphI-F and HY01fatA-com-XbaI-R to complement ΔfatA. The PCR fragments thus obtained were digested with restriction enzymes, and cloned into pMMB208 digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes (Morales et al. 1991). The pMMB208 derivatives were then conjugated into V. harveyi strains as described before.

Siderophore cross-feeding bioassays

Cross-feeding assays to test the ferric-siderophore utilization were performed as previously described (Tolmasky et al. 1988). To assess anguibactin production by V. harveyi derivatives, V. anguillarum strain CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA (Table 1) was used as an indicator strain of ferric-anguibactin transport (Naka and Crosa 2012). Vibrio harveyi HY01 derivatives were used as indicator strains to test their ability to transport ferric-anguibactin. Vibrio anguillarum and V. harveyi strains were grown overnight in AB broth at 25°C. Both 2× AB broth and 1.4% agarose (or 2% agarose) were separately prepared and autoclaved, and ethylenediamine-di-(o-hydroxyphenylacetic) acid (EDDA) for the V. anguillarum indicator strain or 2,2′-dipyridyl (DIP) for the V. harveyi indicator strains (and IPTG [1 mmol/L] and Cm [10 μg/mL] as needed) were added to 2× AB broth. Iron limitation conditions were obtained using EDDA for V. anguillarum and DIP for V. harveyi. This last bacterium needed very high concentrations of EDDA in the media to achieve distinct growth inhibition, possibly due to the different cell penetration of the two compounds (Chart et al. 1986). The supplemented AB broth was mixed 50:50 with 1.4% agarose (or 2% agarose). Overnight culture of the indicator strains (5 μL/mL) was added to the medium adjusted to approximately 40°C. After solidification, iron sources, the bacteria-producing siderophore, or purified siderophores were spotted on the plates. The plates were incubated at 25°C; growth halos around the spots were monitored and recorded after overnight incubation.

Extraction of large plasmids

Plasmids of V. harveyi, V. anguillarum, and Sinorhizobium meliloti were extracted using the modified Eckhardt method described by Hynes et al. (1985) with a slight modification (in-gel lysis method). Briefly, 0.7% horizontal agarose gel was prepared using 1× Tris Borate (TB) buffer. After solidification, the material between the comb and the negative electrode end of the gel was removed, and the empty space was filled with 0.4% agarose in TB buffer with addition of 1% SDS. Overnight cultures were diluted in fresh media; LM for vibrios and TY for S. meliloti, and incubated until OD600 reached ∼0.3. Then, 200 μL of culture was mixed with 200 μL of 0.02% sarkosyl dissolved in TE buffer. After gentle inversion, the samples were centrifuged at 17,000g for 2 min, the culture supernatant was carefully removed and the bacterial cells were resuspended in 20 μL of lysis solution (20% sucrose, 105 units/100 mL lysozyme and 102 units/100 mL RNase in TE buffer). The samples were then loaded on the gel, and the electrophoresis was performed at 20 V for 20 min followed by 120 V for 3.5 h. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with GelRed (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA) overnight, and the image was captured by the Gel Logic 100 Imaging System (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY).

Purification and analysis of siderophore anguibactin

Anguibactin was purified from V. harveyi strain HY01 using the method described previously (Actis et al. 1986). All glassware used for anguibactin purification was washed with 0.1 mol/L HCl prior to the purification to exclude iron. The purified anguibactin was checked by bioassay as well as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and nominal masses of the ion species (m/z) of the purified siderophore were determined by mass spectrometry at the BioAnalytical Shared Resource Core Facility at OHSU using a Thermo Electron LCQ Advantage ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source. The full electrospray ionization-mass spectra and those with collision energy 30% (MS2) were both acquired in a positive mode using as mobile phase 1:1 methanol:water for the full scan and 0.1% formic acid for MS2.

Extraction and analysis of outer membrane fractions

Vibrio harveyi strains were grown in iron rich (30 mL AB plus 10 μg/mL ferric ammonium citrate [FAC]) and iron limiting (30 mL AB broth plus 30 μmol/L DIP) until exponential phase (OD600 ∼0.3). Outer membrane fractions of V. harveyi strains were extracted by using sodium lauroyl sarcosinate (sarkosyl) as described before (Naka and Crosa 2012). Briefly, V. anguillarum was grown in CM9 medium until late-exponential phase. Bacteria were harvested, and pellets were resuspended into 10 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.6). The bacterial cells were broken by sonication, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was transferred to another tube, and the total membranes were collected by centrifuging the tubes at 20,000g for 60 min. To extract outer membrane fractions, the membrane fractions were resuspended in 1.5% sodium lauroyl sarcosinate, incubated for 2 h at 4°C, and centrifuged at 20,000g for 1 h at 4°C. Extracted outer membrane fractions were resuspended into 30 μL of distilled water, and 5 μL of samples was subjected to SDS-PAGE using Criterion™ XT Precast Gel (10% Bis–Tris; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 5 h at 80 V at 4°C. One portion of the gel was stained with Bio-Safe™ Coomassie G-250 stain (Bio-Rad) to visualize outer membrane proteins. The other portion of the gel was used for Western blotting to detect the FatA protein using anti-V. anguillarum FatA polyclonal antibody. The procedure before detection of signals was performed following the protocol described before (Naka et al. 2008). Signals were detected using the Luminata Western HRP Substrates (Millipore Corp, Bedford, MA) following the manufacture's instruction, and imaged by using Image Quant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Results

Anguibactin biosynthesis and transport cluster

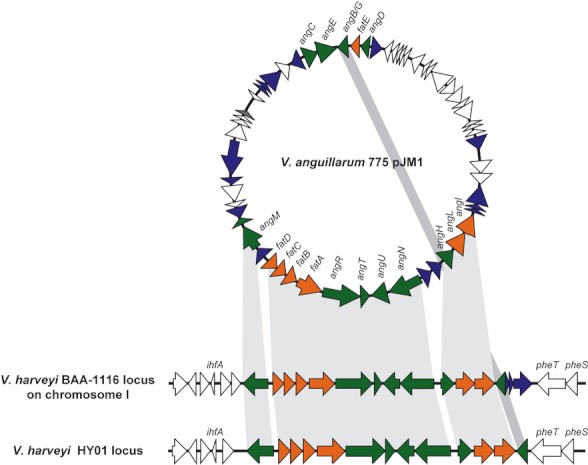

Our BLAST search revealed that two sequenced V. harveyi strains, BAA-1116 and HY01, carry a homolog of the V. anguillarum angR gene encoded on the pJM1 plasmid. Further analysis unveiled that homologs of the majority of the genes involved in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport found in the pJM1 plasmid are located on the same genetic region in these two V. harveyi strains (Fig. 1), whereas other genes required for anguibactin biosynthesis are found elsewhere on the chromosome. Comparative analyses of the predicted products of the pJM1 genes with those of cognate genes present in V. harveyi showed that they have 63–84% identity and 77–93% similarity at the amino acid level depending on the gene (Table 2), while the products of the cognates genes present in the two different V. harveyi strains showed 92–99% identity and 97–100% similarity (Table 3). The predicted anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes found in the chromosome of these two V. harveyi strains are found between ihfA (himA), which encodes the integration host factor alpha subunit, and pheST, which encodes a phenylalanine tRNA synthetase (Mechulam et al. 1985; Brown 2001; Fig. 1 and Table 3). Three genes potentially encoding transposases were located in the anguibactin cluster of strain BAA-1116 but not of strain HY01. It is of interest that highly related homologs of these genes were found on the pJM1 plasmid (two loci, ORF16-18 and ORF46-48, with three genes each annotated as orf1-3 ISVme). Furthermore, these transposase genes were frequently found in the BAA-1116 chromosome and plasmid, as well as in the V. anguillarum 775 chromosomes (data not shown). However, no homologs of these genes were detected in the HY01 draft genome sequence. Given that the anguibactin cluster was placed close to the pheST t-RNA locus, it could possibly be a pathogenicity island horizontally acquired during evolution. However, we did not find a clear difference in the GC content between the anguibactin cluster (BAA-1116, 44.8%: HY01, 45.0%) and the V. harveyi genome (BAA-1116, 45.4%: HY01, 45.6%).

Figure 1.

The anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes are conserved in Vibrio anguillarum pJM1 and two Vibrio harveyi strains, BAA-1116 and HY01. Gray-shaded parts indicate that these genes are conserved between the three clusters. The green-filled arrows, orange-filled arrows, and blue-filled arrows represent the genes involved in anguibactin biosynthesis, anguibactin transport, and transposon elements, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of genes on the pJM1 plasmid and on the Vibrio harveyi anguibactin locus

| V. harveyi HY01 | V. harveyi BAA-1116 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJM1 ORF number (gene name) | Accession number | Identity | Similarity | Accession number | Identity | Similarity |

| 1 (angM) | ZP_01986345 | 444/706 (63%) | 547/706 (77%) | VIBHAR_02109 | 445/706 (63%) | 546/706 (77%) |

| 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 (fatD) | ZP_01986358 | 263/314 (84%) | 290/314 (92%) | VIBHAR_02108 | 264/314 (84%) | 291/314 (93%) |

| 4 (fatC) | ZP_01986350 | 245/317 (77%) | 276/317 (87%) | VIBHAR_02107 | 246/317 (78%) | 276/317 (87%) |

| 5 (fatB) | ZP_01986380 | 265/324 (82%) | 298/324 (92%) | VIBHAR_02106 | 262/324 (81%) | 298/324 (92%) |

| 6 (fatA) | ZP_01986352 | 564/725 (78%) | 643/725 (89%) | VIBHAR_02105 | 560/725 (77%) | 638/725 (88%) |

| 7 (angR) | ZP_01986376 | 666/1046 (64%) | 816/1046 (78%) | VIBHAR_02104 | 661/1046 (63%) | 813/1046 (78%) |

| 8 (angT) | ZP_01986361 | 159/249 (64%) | 198/249 (80%) | VIBHAR_02103 | 127/202 (63%) | 163/202 (81%) |

| 9 (angU) | ZP_01986389 | 350/439 (80%) | 387/439 (88%) | VIBHAR_02102 | 347/439 (79%) | 386/439 (88%) |

| 10 (angN) | ZP_01986387 | 659/952 (69%) | 775/952 (81%) | VIBHAR_02101 | 653/952 (69%) | 770/952 (81%) |

| 11–12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13 (angH) | ZP_01986363 | 313/386 (81%) | 351/386 (91%) | VIBHAR_02100 | 311/386 (81%) | 350/386 (91%) |

| 14 (angL) | ZP_01986390 | 384/536 (72%) | 458/536 (85%) | VIBHAR_02099 | 384/536 (72%) | 454/536 (85%) |

| 15 (angI) | ZP_01986392 | 372/532 (70%) | 444/532 (83%) | VIBHAR_02098 | 371/532 (70%) | 440/532 (83%) |

| 16–40 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 41 (angB/G) | ZP_01986357 | 228/288 (79%) | 258/288 (90%) | VIBHAR_02097 | 204/256 (80%) | 229/256 (89%) |

| 42–59 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA, not applicable (no homolog in the V. harveyi anguibactin locus).

Table 3.

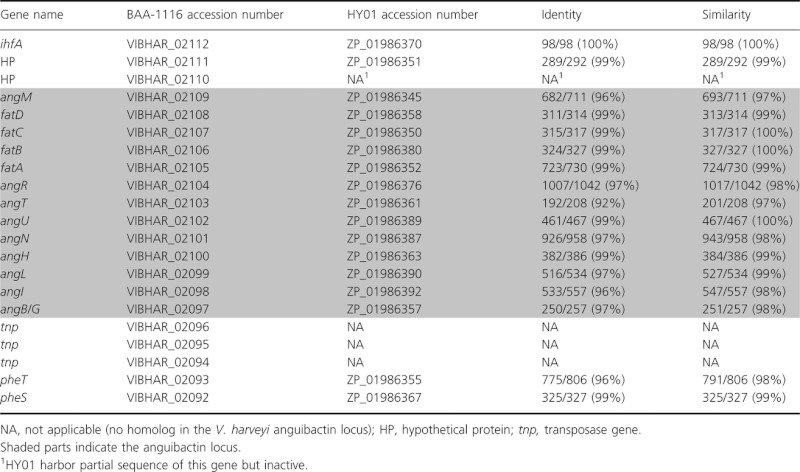

Comparison of genes on the anguibactin locus of Vibrio harveyi BAA-1116 and HY01

|

According to the whole-genome sequence data of V. harveyi BAA-1116 in Genbank, the anguibactin cluster is located on chromosome 1. Due to the fact that gap closure of V. harveyi HY01 DNA contigs has not been completed yet, we could not determine whether the anguibactin cluster is located on the chromosome of this strain. We first determined whether V. harveyi HY01 harbors any plasmids using the modified in-gel lysis method that can identify very large plasmids as described in Materials and Methods. The results indicate that this strain carries one plasmid with a molecular size between 8 and 13 kb estimated by gel electrophoresis using supercoiled DNA markers (Fig. S1). The cluster between ihfA and pheST harboring anguibactin locus expands >29 kb, which is larger than the size of the observed plasmid. As positive controls of this method, large plasmids were successfully detected from V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) harboring the 65-kb pJM1 plasmid, V. harveyi BAA-1116 harboring the 89-kb pVIBHAR plasmid, and Sinorhizobium meliloti 102F34 harboring 100-, 150-, and 220-kb plasmids (Cook et al. 2001; Fig. S1). From these experiments, we conclude that the anguibactin cluster of strain HY01 is also located on the chromosome rather than on the plasmid.

Anguibactin production by V. harveyi

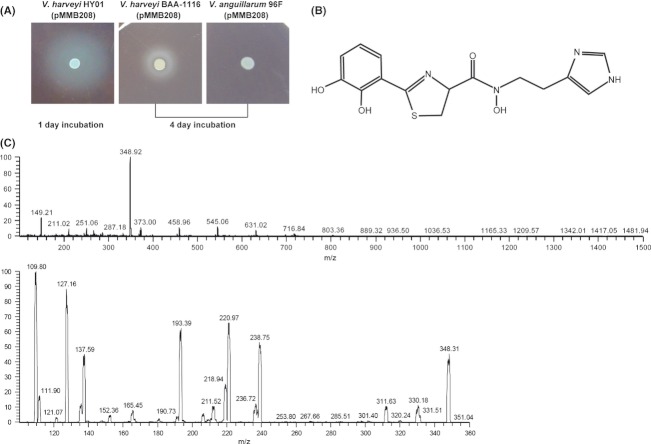

The high similarity of the V. harveyi anguibactin gene cluster with that found in the V. anguillarum 775 pJM1 plasmid suggested that V. harveyi BAA-1116 and HY01 likely produce anguibactin. This possibility was tested with siderophore utilization assays using V. anguillarum CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA as a reporter strain. In V. anguillarum, FvtA is functional for both ferric-vanchrobactin and ferric-enterobactin transport, while FetA is involved in ferric-enterobactin transport (Balado et al. 2009; Naka and Crosa 2012). As shown in Figure 2A, CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA can utilize siderophores produced by either V. harveyi BAA-1116 or HY01 indicating that the siderophores produced by these strains are likely anguibactin. However, the data indicated that strain HY01 produces more anguibactin than BAA-1116; a larger growth halo was produced with the supernatants from HY01 after 1 day of incubation, while a smaller halo was detected with BAA-1116 supernatants after 4 days of incubation under the same experimental conditions. Based on these observations, we decided to use HY01 for further characterization of the anguibactin-mediated system expressed by V. harveyi.

Figure 2.

Anguibactin production from Vibrio harveyi. (A) Bioassay to test anguibactin production. CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA was used as an anguibactin indicator strain. EDDA (40 μmol/L) and Cm (10 μg/mL) were added into AB media with the indicator strain. Five microliters of overnight culture of V. harveyi HY01 (pMMB208), V. harveyi BAA-1116 (pMMB208), and Vibrio anguillarum 96F (pMMB208) grown in AB broth with Cm was spotted on the plates, and incubated at 25°C. Presence of growth halos around spots was checked every 24 h. Vibrio anguillarum 96F (pMMB208) is a vanchrobactin producer and was used as a negative control. (B) Structure of anguibactin from V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) (Jalal et al. 1989). (C) Confirmation of anguibactin biosynthesis in the V. harveyi HY01 strain. Positive mode electrospray ionization-mass spectra of the purified siderophores without (above) and with (below) 30% collision energy. The nominal masses (m/z) of the parental ion species and different fragmentation products are indicated in the spectra.

As the ferric-anguibactin outer membrane receptor FatA has been shown to be able to transport at least two different siderophores, anguibactin and acinetobactin (Dorsey et al. 2004), it was important to use a different approach to ensure that the siderophore is indeed anguibactin. The structure of anguibactin from V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) determined previously (Jalal et al. 1989) is shown in Figure 2B. We purified the siderophore from strain HY01 and performed mass spectrometry analysis. As shown in Figure 2C, a strong peak with a mass 348.92 was detected by ElectroSpray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the siderophore isolated and purified from HY01 iron-limiting culture supernatants. The molecular mass of this peak is in agreement with the molecular weight of anguibactin from V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) reported before (Actis et al. 1986). The nature of the siderophore produced by V. harveyi HY01 was further confirmed by tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis; the fragmentation pattern produced by the siderophore isolated from HY01 iron-limiting culture supernatants was identical (within the error limits) to the pattern by anguibactin purified from Vibrio sp. DS40M4 (Sandy et al. 2010). Taken together, these results confirm that V. harveyi HY01 actually produces anguibactin.

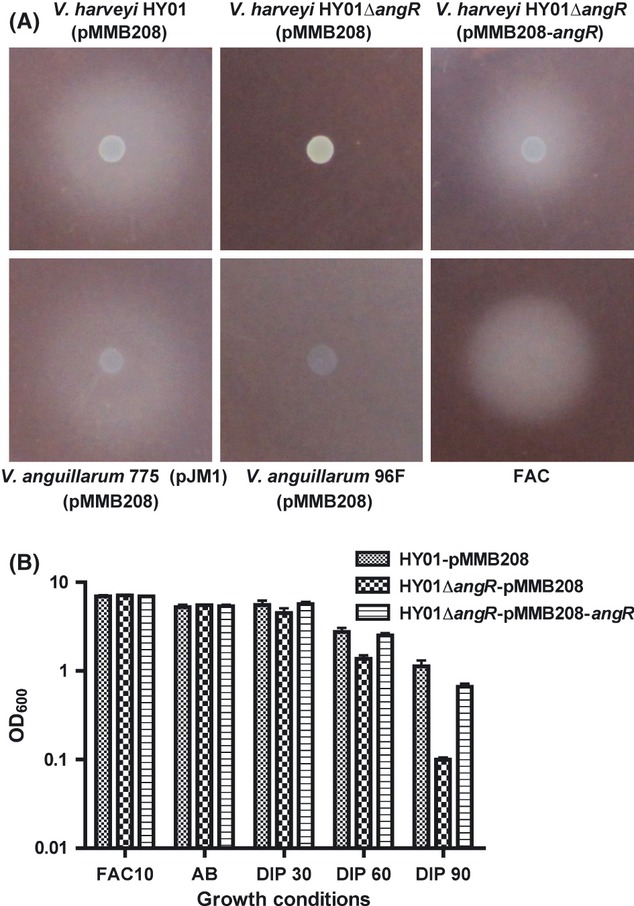

AngR is involved in the biosynthesis of anguibactin and is required for the growth under iron-limiting conditions

To check whether angR is required for the anguibactin biosynthesis in V. harveyi as it was previously described in V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) (Wertheimer et al. 1999), we constructed and tested the V. harveyi HY01ΔangR deletion mutant. Our bioassay results (Fig. 3A) showed that this derivative did not produce any anguibactin when compared to the isogenic HY01 wild-type strain. However, production of anguibactin was restored when the V. harveyi HY01ΔangR was trans complemented with the wild-type angR allele. We also compared the growth rate of the parental HY01 strain and the isogenic angR mutant under different iron growth conditions (Fig. 3B). The mutation in angR did not affect the growth of V. harveyi HY01 in iron sufficient conditions, while increasing the amount of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (DIP), which creates iron limitation in the AB medium, impaired the growth of the angR mutant as compared with the wild-type strain. Complementation of the mutant with the wild-type angR gene in trans restored growth to wild-type levels. From these results, we conclude that AngR is important for V. harveyi to produce anguibactin and survive under iron-limiting conditions.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the angR gene in Vibrio harveyi HY01. (A) The angR gene is essential for the anguibactin production in V. harveyi HY01. Vibrio anguillarum CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA was used as an anguibactin indicator strain. EDDA (40 μmol/L) and Cm (10 μg/mL) were added into AB media with the indicator strain. Five microliters of an overnight culture of V. harveyi HY01 (pMMB208), V. harveyi HY01ΔangR (pMMB208), V. harveyi HY01ΔangR (pMMB208-angR), Vibrio anguillarum 775 (pJM1) (pMMB208), and V. anguillarum 96F (pMMB208) grown in AB broth with Cm and 1 μL of 1 mg/mL ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) were spotted on the plates and were incubated at 25°C. Presence of growth halos around spots was checked after 24-h incubation. V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) (pMMB208) and FAC are positive controls. Vibrio anguillarum 96F (pMMB208) is a vanchrobactin producer and was used as a negative control. (B) Anguibactin production promotes the growth of V. harveyi in iron-limiting conditions. Fifty microliters of overnight culture (adjusted OD600 to 1) grown in 5 mL AB broth with Cm (10 μg/mL) was inoculated into AB broth containing Cm (10 μg/mL) and IPTG (1 mmol/L) (AB) or with addition of 10 μg/mL ferric ammonium citrate (FAC10), 30 μmol/L dipyridyl (DIP30), 60 μmol/L dipyridyl (DIP60), or 90 μmol/L dipyridyl (DIP90). OD600 was measured after 24-h incubation at 25°C. Experiments were repeated five times, and the error bars show standard deviation.

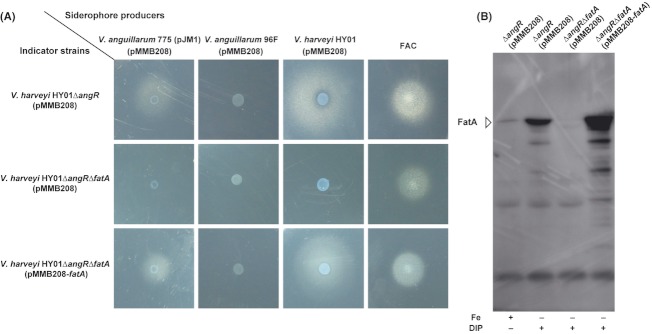

Vibrio harveyi HY01 FatA homolog is involved in the ferric-anguibactin utilization and located on the outer membrane fractions

In V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1), FatA is the outer membrane ferric-anguibactin receptor that plays an essential role in the uptake of the ferric-anguibactin complex from the external environment to the periplasmic space (Lopez and Crosa 2007). The high similarity of amino acid sequences of FatA from V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) and V. harveyi HY01 motivated us to characterize the function and the localization of the FatA protein in V. harveyi HY01. To evaluate whether FatA is essential for the ferric-anguibactin utilization in V. harveyi, we constructed a ΔfatA mutant in strain HY01 and performed bioassays. Our results (Fig. 4A) show that the ΔfatA mutant cannot utilize ferric-anguibactin to grow in iron-limiting conditions, while the wild-type strain as well as the ΔfatA mutant complemented with the fatA gene enhances the growth by acquiring anguibactin from both V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1) and V. harveyi HY01. These results indicate that in V. harveyi HY01, fatA is essential to acquire ferric-anguibactin as an iron source.

Figure 4.

The fatA gene in Vibrio harveyi HY01 encodes the ferric-anguibactin outer membrane receptor protein. (A) The fatA gene is involved in the ferric-anguibactin transport in V. harveyi HY01. V. harveyi HY01ΔangR (pMMB208), V. harveyi HY01ΔangRΔfatA (pMMB208), and V. harveyi HY01ΔangRΔfatA (pMMB208-fatA) were used as indicator strains. DIP (100 μmol/L), IPTG (1 mmol/L), and Cm (10 μg/mL) were supplemented into AB medium with indicator strains. Five microliters of overnight culture of V. harveyi HY01 (pMMB208) and Vibrio anguillarum 775 (pJM1) (pMMB208) and 1 μL of 1 mg/mL ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) were spotted on the plates. Presence of growth halos around spots was checked after 24-h incubation at 25°C. (B) The FatA protein locates on the outer membrane of V. harveyi. Vibrio harveyi HY01ΔangR (pMMB208), V. harveyi HY01ΔangRΔfatA (pMMB208), and V. harveyi HY01ΔangRΔfatA (pMMB208-fatA) were grown in AB medium until exponential phase (OD600 ∼0.3). Outer membrane proteins were then extracted using sarkosyl as described in Materials and Methods. Western blots were performed using anti-V. anguillarum FatA polyclonal antibody.

To investigate whether FatA localizes in the outer membrane fractions of V. harveyi HY01 as it was previously described in V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1), outer membrane proteins were extracted using sodium lauroyl sarcosinate from V. harveyi HY01 grown in iron-rich and iron-limiting conditions, and Western blotting using anti-V. anguillarum FatA was performed to detect V. harveyi FatA (Fig. 4B). A small amount of V. harveyi FatA was detected when the cells were grown in iron-rich conditions, while much more V. harveyi FatA was observed when the cells were grown under iron limitation. Deletion of fatA in V. harveyi caused complete loss of FatA protein in the outer membrane fraction, while the V. harveyi ΔfatA complemented with the V. harveyi fatA showed very high levels of FatA in the outer membrane fraction. These results indicate that V. harveyi FatA locates on the outer membrane of V. harveyi HY01, and the expression of FatA is upregulated in iron-limiting conditions.

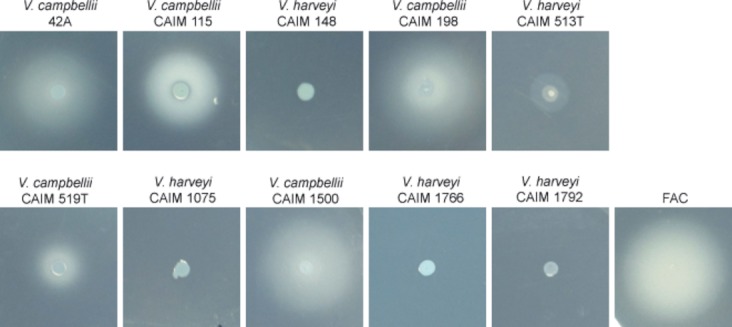

Anguibactin production from various strains

Recently, we determined the genome sequence of V. campbellii DS40M4 that produces anguibactin (Dias et al. 2012), and our DNA sequence analysis showed that this strain also carries an almost identical anguibactin locus to the one found in the two V. harveyi strains used in this work. However, we did not find the anguibactin cluster in the draft genome sequence of V. harveyi CAIM 1792 (Espinoza-Valles et al. 2012). Lin et al. (2010) proposed that V. harveyi BAA-1116 and HY01 should be classified as V. campbellii based on microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and multilocus sequence analyses (MLSA). According to this paper, V. harveyi CAIM 1792 is the only V. harveyi strain in which whole-genome sequence data are available in a public database. We checked anguibactin production from five strains of V. harveyi and five strains of V. campbellii as classified by Lin et al. (2010). Our results showed that strains classified as V. harveyi do not produce anguibactin, while strains classified as V. campbellii produce anguibactin when CGH and MLSA were applied to classify bacterial species (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of anguibactin production from various strains. Vibrio anguillarum CC9-16ΔfvtAΔfetA was used as an anguibactin indicator strain. EDDA (40 μmol/L) was added into AB media with the indicator strain. Higher concentration of agarose (1%) was supplemented into AB media to reduce swarming of some strains. Overnight culture grown in AB broth was spotted on the plates, and the plates were incubated at 25°C. Presence of growth halos around spots was checked after 24-h incubation. Clear zone around the spot observed in Vibrio harveyi CAIM 513T exhibits swarming but not anguibactin production. Anguibactin production was never detected in anguibactin production negative strains shown in this figure even after incubation for several days. Experiments were repeated three times, and this figure shows a representative.

Discussion

Many V. anguillarum O1 serotype strains carry the 65-kb pJM1-type plasmid encoding the siderophore anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes. The anguibactin system is essential for V. anguillarum to survive under iron-limiting conditions including those found in their host organisms. Thus, the curing of the pJM1 plasmid causes growth defect in iron-deficient conditions. Our previous work suggested that a V. anguillarum pJM1-less strain acquired the pJM1 plasmid during evolution, and gained the very high-affinity iron transport anguibactin system, following inactivation of the original chromosomally-mediated siderophore vanchrobactin (Naka et al. 2008). Anguibactin production has been found only in V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains harboring pJM1-like plasmids, and in the Vibrio sp. DS40M4 isolate (later named as V. campbellii DS40M4) so far (Sandy et al. 2010).

In this work, we report that two V. harveyi strains, BAA-1116 and HY01, produce and utilize anguibactin. For the first time, we identified and genetically characterized a V. harveyi gene cluster carrying the majority of homologous genes encoding anguibactin biosynthesis and transport proteins found in the pJM1 plasmid of V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1). Homologs of the pJM1 encoding anguibactin biosynthesis genes such as angC, angE, and dhap involved in 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) biosynthesis and angD, encoding a phosphopantetheinyl transferase, were not found in these V. harveyi anguibactin clusters. However, in the case of V. anguillarum, functional homologs of those genes are located on the chromosome locus associated with another siderophore biosynthesis and transport system (Alice et al. 2005; Naka et al. 2008). Interestingly, in the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii, entA, which is essential for DHBA biosynthesis, is located outside of the acinetobactin gene cluster that otherwise contains all the genes needed for acinetobactin biosynthesis, export, and transport (Penwell et al. 2012). It appears that in V. harveyi, we can find a similar situation with the homologs of angC, angE, and angD. These genes exist in a different location on the chromosome (AngC homolog [BAA-1116: VIBHAR_01398 49% identity and 66% similarity, HY01: A1Q_1381 50% identity and 66% similarity], AngE homolog [BAA-1116: VIBHAR_01399 55% identity 70% similarity, HY01: A1Q_1380 56% identity and 70% similarity], and AngD homolog [BAA-1116: VIBHAR_01403 33% identity and 57% similarity, HY01: A1Q_1376 33% identity and 57% similarity]) and those homologs are included in the same cluster potentially involved in siderophore biosynthesis and transport.

Characterization of two genes, angR and fatA located on the V. harveyi HY01 chromosome locus, unveiled that these genes are involved in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport, respectively, as is the case of V. anguillarum. These findings suggest that the anguibactin cluster found in the pJM1 plasmid of V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains could have originated from the chromosome locus found in the V. harveyi (or V. campbellii). Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the V. harveyi chromosomally-mediated anguibactin locus was acquired from the pJM1-type plasmid.

Our bioassay results showed that V. campbellii rather than V. harveyi produces anguibactin following the definition proposed by Lin et al. (2010) using microarray-based CGH and MLSA. As we still need to wait for the conclusion of the “V. harveyi or V. campbellii” debate, in this study we chose to keep the original designation pending official taxonomic revision. It is of interest that only the strains classified as V. campbellii by CGH and MLSA produce and utilize anguibactin.

In summary, for the first time, we identified and characterized the chromosomally encoded anguibactin cluster from V. harveyi. This finding indicates that the anguibactin cluster found in the pJM1 plasmid of V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains could possibly have been acquired from the chromosome locus found in V. harveyi.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants GM64600 to J. H. C. and AI070174 to L. A. A. We thank Michael O'Connell Ph.D., for providing us the Sinorhizobium meliloti strain and the protocol of “In gel lysis method,” Varaporn Vuddhakul Ph.D., for V. harveyi HY01, and Fabiano F. Thompson Ph.D., for V. harveyi 34A. We also thank members of the Crosa laboratory, Lidia M. Crosa Ph.D., Shreya Datta Ph.D., Ryan J. Kustusch Ph.D., and Moqing Liu Ph.D., for reviewing the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. The V. harveyi HY01 anguibactin cluster is not located on the plasmid. Presence of plasmids from V. harveyi HY01 was examined using “In gel lysis method” as described in Materials and Methods. Sinorhizobium meliloti 102F34 containing 100, 150 and 220 kb plasmids (Cook et al. 2001), V. harveyi BAA-1116 containing the 89 kb pVIBHAR plasmid, V. anguillarum 775(pJM1) containing the 65 kb pJM1 plasmid were used as controls. Supercoiled DNA Marker Set (Epicentre, Madison, WI) were used to estimate the size of supercoiled plasmid DNA. Experiments were repeated three times, and the picture is a representative.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

References

- Actis LA, Fish W, Crosa JH, Kellerman K, Ellenberger SR, Hauser FM, et al. Characterization of anguibactin, a novel siderophore from Vibrio anguillarum 775 (pJM1) J. Bacteriol. 1986;167:57–65. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.57-65.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Actis LA, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. Vibriosis. In: Woo PTK, Bruno DW, editors. Vibriosis. Oxfordshire, U.K: CABI International; 2011. pp. 570–605. [Google Scholar]

- Alice AF, Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Plasmid- and chromosome-encoded redundant and specific functions are involved in biosynthesis of the siderophore anguibactin in Vibrio anguillarum 775: a case of chance and necessity? J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2209–2214. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2209-2214.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin B, Zhang XH. Vibrio harveyi: a significant pathogen of marine vertebrates and invertebrates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;43:119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. A gene cluster involved in the biosynthesis of vanchrobactin, a chromosome-encoded siderophore produced by Vibrio anguillarum. Microbiology. 2006;152:3517–3528. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. Biosynthetic and regulatory elements involved in the production of the siderophore vanchrobactin in Vibrio anguillarum. Microbiology. 2008;154:1400–1413. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. FvtA is the receptor for the siderophore vanchrobactin in Vibrio anguillarum: utility as a route of entry for vanchrobactin analogues. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:2775–2783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02897-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR. Genomic and phylogenetic perspectives on the evolution of prokaryotes. Syst. Biol. 2001;50:497–512. doi: 10.1080/10635150117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chart H, Buck M, Stevenson P, Griffiths E. Iron regulated outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli: variations in expression due to the chelator used to restrict the availability of iron. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1986;132:1373–1378. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-5-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MA, Osborn AM, Bettandorff J, Sobecky PA. Endogenous isolation of replicon probes for assessing plasmid ecology of marine sediment microbial communities. Microbiology. 2001;147:2089–2101. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH. A plasmid associated with virulence in the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum specifies an iron-sequestering system. Nature. 1980;284:566–568. doi: 10.1038/284566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH, Walsh CT. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:223–249. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.223-249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuiv PO, Clarke P, Lynch D, O'Connell M. Identification of rhtX and fptX, novel genes encoding proteins that show homology and function in the utilization of the siderophores rhizobactin 1021 by Sinorhizobium meliloti and pyochelin by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2996–3005. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.2996-3005.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M, Stork M, Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Farrell D, Welch TJ, et al. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pJM1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5822–5830. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5822-5830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias GM, Thompson CC, Fishman B, Naka H, Haygood MG, Crosa JH, et al. Genome sequence of the marine bacterium Vibrio campbellii DS40M4, isolated from open ocean water. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:904. doi: 10.1128/JB.06583-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Connerly PL, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH, Actis LA. The siderophore-mediated iron acquisition systems of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Vibrio anguillarum 775 are structurally and functionally related. Microbiology. 2004;150:3657–3667. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Valles I, Soto-Rodriguez S, Edwards RA, Wang Z, Vora GJ, Gomez-Gil B. Draft genome sequence of the shrimp pathogen Vibrio harveyi CAIM 1792. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:2104. doi: 10.1128/JB.00079-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannauer M, Barda Y, Mislin GL, Shanzer A, Schalk IJ. The ferrichrome uptake pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves an iron release mechanism with acylation of the siderophore and recycling of the modified desferrichrome. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:1212–1220. doi: 10.1128/JB.01539-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes MF, Simon R, Puhler A. The development of plasmid-free strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by using incompatibility with a Rhizobium meliloti plasmid to eliminate pAtC58. Plasmid. 1985;13:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal MAF, Hossain MB, Sanders-Loehr D, Van der Helm J, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Structure of anguibactin, a unique plasmid-related bacterial siderophore from the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos ML, Salinas P, Toranzo AE, Barja JL, Crosa JH. Chromosome-mediated iron uptake system in pathogenic strains of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1920–1925. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1920-1925.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Wang Z, Malanoski AP, O'Grady EA, Wimpee CF, Vuddhakul V, et al. Comparative genomic analyses identify the Vibrio harveyi genome sequenced strains BAA-1116 and HY01 as Vibrio campbellii. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010;2:81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Characterization of ferric-anguibactin transport in Vibrio anguillarum. Biometals. 2007;20:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechulam Y, Fayat G, Blanquet S. Sequence of the Escherichia coli pheST operon and identification of the himA gene. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163:787–791. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.787-791.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton DL, O'Toole R, Horstedt P, Wolf-Watz H. Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:1310–1319. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1310-1319.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales VM, Backman A, Bagdasarian M. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene. 1991;97:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Crosa JH. Genetic Determinants of Virulence in the Marine Fish Pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Fish Pathol. 2011;46:1–10. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.46.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Crosa JH. Identification and characterization of a novel outer membrane protein receptor FetA for ferric-enterobactin transport in Vibrio anguillarum 775 (pJM1) Biometals. 2012;25:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9488-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Reactivation of the vanchrobactin siderophore system of Vibrio anguillarum by removal of a chromosomal insertion sequence originated in plasmid pJM1 encoding the anguibactin siderophore system. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Chen Q, Mitoma Y, Nakamura Y, McIntosh-Tolle D, Gammie AE, et al. Two replication regions in the pJM1 virulence plasmid of the marine pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Plasmid. 2012;67:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens L, Busico-Salcedo N. Vibrio harveyi: pretty problems in paradise. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, editors. The biology of vibrios. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. pp. 266–280. [Google Scholar]

- Penwell WF, Arivett BA, Actis LA. The Acinetobacter baumannii entA gene located outside the acinetobactin cluster is critical for siderophore production, iron acquisition and virulence. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond KN, Dertz EA. Biochemical and physical properties of siderophores. In: Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM, editors. Iron transport in bacteria. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2004. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Reimmann C. Inner-membrane transporters for the siderophores pyochelin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enantio-pyochelin in Pseudomonas fluorescens display different enantioselectivities. Microbiology. 2012;158:1317–1324. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.057430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandy M, Han A, Blunt J, Munro M, Haygood M, Butler A. Vanchrobactin and anguibactin siderophores produced by Vibrio sp. DS40M4. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1038–1043. doi: 10.1021/np900750g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system in vivo genetic engineering transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:787–796. [Google Scholar]

- Soengas RG, Anta C, Espada A, Paz V, Ares IR, Balado M, et al. Structural characterization of vanchrobactin, a new catechol siderophore produced by the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum serotype O2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7113–7116. [Google Scholar]

- Taga ME, Xavier KB. Methods for analysis of bacterial autoinducer-2 production. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01c01s23. Chapter 1:Unit1C.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FL, Iida T, Swings J. Biodiversity of vibrios. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:403–431. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.403-431.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Genetic analysis of the iron uptake region of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1: molecular cloning of genetic determinants encoding a novel trans activator of siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1913–1919. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1913-1919.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer AM, Verweij W, Chen Q, Crosa LM, Nagasawa M, Tolmasky ME, et al. Characterization of the angR gene of Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in virulence. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:6496–6509. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6496-6509.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann G. Ecology of siderophores. In: Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM, editors. Iron transport in bacteria. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2004. pp. 437–450. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.