Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Childhood cancer mortality has substantially declined worldwide as a result of significant advances in global cancer care. Because limited information is available in Brazil, we analyzed trends in childhood cancer mortality in five Brazilian regions over 29 years.

METHODS:

Data from children 0-14 years old were extracted from the Health Mortality Information System for 1979 through 2008. Age-adjusted mortality rates, crude mortality rates, and age-specific mortality rates by geographic region of Brazil and for the entire country were analyzed for all cancers and leukemia. Mortality trends were evaluated for all childhood cancers and leukemia using joinpoint regression.

RESULTS:

Mortality declined significantly for the entire period (1979-2008) for children with leukemia. Childhood cancer mortality rates declined in the South and Southeast, remained stable in the Middle West, and increased in the North and Northeast. Although the mortality rates did not unilaterally decrease in all regions, the age-adjusted mortality rates were relatively similar among the five Brazilian regions from 2006-2008.

CONCLUSIONS:

Childhood cancer mortality declined 1.2 to 1.6% per year in the South and Southeast regions.

Keywords: Mortality Rate, Childhood Cancer, Leukemia, Trends

INTRODUCTION

Although mortality rates due to childhood leukemia and other cancers have substantially declined in several parts of the world, significant differences in specific patterns have been observed in certain regions (1-3). Favorable trends are less pronounced in less-developed regions, including Latin America (1,4,5). Cancer mortality statistics in low- and middle-income countries suffer from predictable sources of error, including inaccurate death certificates, misdiagnosis, and underreporting (1,5,6). Brazil demonstrates great heterogeneity in cultural and socioeconomic patterns across five geographic regions. In the 1970s, death certification quality, completeness, and reporting of ill-defined deaths differed among the five regions, with adequate coverage in the Southeast and South and poor coverage in the North and Northeast. National government agencies have exerted continuous efforts to improve death certification quality, and the proportion of ill-defined deaths has achieved acceptable quality in all regions since 2006 (6).

The objectives of this study were to describe childhood cancer and leukemia mortality in the five geographic regions of Brazil and to evaluate trends in mortality over 29 years (1979-2008) using joinpoint regression analysis (7).

METHODS

Brazil was divided into five geographic regions: North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Middle West (Table 1). Data from children 0-14 years old were extracted from the databases of the Brazilian Health Mortality Information System for the years 1979 to 2008. (http://www.datasus.gov.br) The age range of 0-14 years was chosen based on the criteria used by SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End results; www.http://seer.cancer.gov.) and IARC (International Agency for Research in Cancer; http://www.iarc.fr) in their international monographs.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of Brazil and its regions.

| Brazil | North | Northeast | Middle West | Southeast | South | |

| Total Population (2008) | 189,612,814 | 15,142,684 | 53,088,499 | 13,695,944 | 80,187,717 | 27,497,970 |

| Population 0-14 years (2008) | 49,476,645 | 4,956,629 | 15,375,104 | 3,623,141 | 19,056,866 | 6,464,905 |

| GNP* per capita | 14,056.27 | 8,706.43 | 6,663.58 | 17,457.89 | 18,615.63 | 16,020.11 |

| Income less than 1/4 minimum wage per family (%) | 11.33 | 15.49 | 23.10 | 6.80 | 5.50 | 4.84 |

| Illiteracy Rate (% population 15 and more years old) | ||||||

| Male Population | 10.16 | 11.21 | 21.06 | 8.24 | 5.25 | 5.00 |

| Female Population | 9.78 | 10.26 | 17.89 | 8.12 | 6.32 | 5.87 |

| Total | 9.96 | 10.73 | 19.41 | 8.18 | 5.81 | 5.45 |

| Under 5 year Mortality Rate (2007) | 24.07 | 26.32 | 35.2 | 20.18 | 17.08 | 15.11 |

Source: MS/SVS/DASIS/CGIAE/Indicators and Health Information (IDB), 2009. North Region: Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins. Northeast Region: Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, and Sergipe. Southeast Region: Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. South Region: Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, and Santa Catarina. Middle West Region: Brasilia, Goiás, Mato Grosso, and Mato Grosso do Sul. GNP: Gross National Product.

Death-related information was organized according to gender, age group, state (place of residence), and cause of death (malignant neoplasm according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-9 (1979-95) and ICD-10 (1996-2008) (8,9). The analysis included examination of the number of deaths, age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs), crude mortality rates, and age-specific mortality rates (ASMRs) by geographic region and for the entire country. AAMRs were calculated according to all cancer deaths and leukemia, gender, and time period via a direct method using the proposed world population in age groups less than 14 years old (10). For ASMRs, gender and time period were calculated by age groups defined as less than 1, 1-4, 5-9, and 10-14 years. To identify significant changes in the trends for all childhood cancers and leukemia, we performed joinpoint regression analysis to establish the best cut-point period for measuring the trends described elsewhere (www.srab.cancer.gov/joinpoint) (7). Significance was determined with the Monte Carlo Permutation method. The models either incorporated the estimated variation for each point when the responses were AAMRs or used a Poisson model of variation. In addition, the models could also be linear on the log of the response to calculate the annual percentage rate change. Because the proportion of ill-defined deaths achieved a quality control standard (less than 10% in all five Brazilian regions) in 2006-2008, the age-specific mortality rate was analyzed for this period (Supplemental Table 1).

Supplemental Table 1.

Percentage of ill-defined mortality in children (0-14 years old) in Brazil and its regions (1979-2008).

| Years | BRAZIL | NORTH | NORTHEAST | MIDDLE-WEST | SOUTHEAST | SOUTH |

| 1979 | 24.4 | 25.0 | 53.1 | 13.4 | 6.4 | 15.0 |

| 1980 | 26.4 | 25.5 | 54.6 | 12.5 | 5.7 | 14.5 |

| 1981 | 24.7 | 21.9 | 52.1 | 12.9 | 4.7 | 14.6 |

| 1982 | 22.4 | 23.0 | 47.7 | 12.5 | 4.6 | 13.0 |

| 1983 | 23.8 | 23.6 | 47.3 | 13.3 | 4.9 | 12.8 |

| 1984 | 25.6 | 26.1 | 50.1 | 12.8 | 4.6 | 12.6 |

| 1985 | 23.9 | 24.7 | 45.6 | 11.9 | 7.5 | 11.9 |

| 1986 | 24.2 | 26.2 | 45.8 | 12.7 | 7.1 | 11.1 |

| 1987 | 23.5 | 25.4 | 45.1 | 12.6 | 6.6 | 11.2 |

| 1988 | 22.4 | 25.0 | 44.7 | 10.9 | 5.8 | 10.3 |

| 1989 | 20.7 | 24.3 | 41.6 | 9.0 | 5.7 | 10.8 |

| 1990 | 19.7 | 27.9 | 40.2 | 9.4 | 5.7 | 10.3 |

| 1991 | 19.6 | 25.6 | 39.3 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 8.5 |

| 1992 | 18.5 | 24.1 | 36.3 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 8.3 |

| 1993 | 19.2 | 23.6 | 38.0 | 8.3 | 7.0 | 7.8 |

| 1994 | 16.9 | 22.7 | 32.9 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 |

| 1995 | 14.3 | 18.3 | 27.8 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 7.3 |

| 1996 | 12.9 | 17.5 | 25.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.3 |

| 1997 | 11.8 | 17.3 | 23.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| 1998 | 12.7 | 16.9 | 23.0 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| 1999 | 12.2 | 15.8 | 21.2 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 5.3 |

| 2000 | 12.5 | 16.8 | 21.3 | 4.4 | 6.4 | 4.8 |

| 2001 | 10.8 | 14.6 | 17.7 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 4.6 |

| 2002 | 9.9 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 4.5 |

| 2003 | 9.4 | 14.8 | 14.2 | 3.0 | 5.2 | 4.9 |

| 2004 | 8.0 | 13.6 | 11.8 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 3.7 |

| 2005 | 6.3 | 11.3 | 7.8 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| 2006 | 5.4 | 9.8 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| 2007 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 4.0 |

| 2008 | 4.9 | 8.4 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

Source: MS/SVS/DASIS/CGIAE/Sistema de Informação sobre Mortalidade – SIM

RESULTS

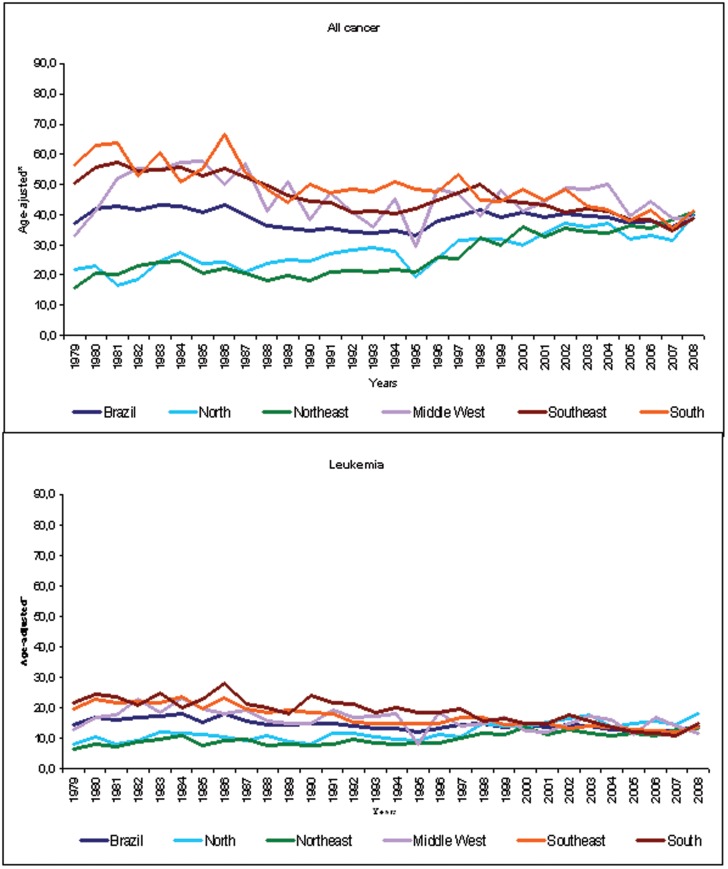

Figure 1) depicts the trends in AAMR from all childhood cancers and from leukemia for 1979-2008 in the entire country and according to the five major regions. The AAMRs showed a trend toward stability in the entire country (36.91 deaths per million in 1979 and 39.83 deaths per million in 2008) for all cancers and a slight decrease for leukemia (14.33 deaths per million in 1979 and 13.83 deaths per million in 2008). The North and Northeast regions experienced increased mortality rates, while the rates decreased in the South and Southeast and were stable in the Middle West (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in age-standardized 0-14 years mortality rates for all childhood cancers and leukemias in Brazil and its 5 different regions.

The joinpoint analysis of the AAMR (ages 0-14 years) for all childhood cancers and leukemia according to gender and region is shown in Table 2. Mortality from all childhood cancers from 1979-2008 demonstrated a slight but significant decline in boys of almost 0.5% per year (average annual percent change (AAPC) = −0.34) and was stable in girls (AAPC = −0.03). In the North and Northeast regions, there was a significant increase of 2 to 3% per year (boys and girls). In the Middle-West, South, and Southeast, the mortality rate decreased significantly from 0.5 to 1.5% per year for boys and girls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Joinpoint analysis for all childhood cancers and leukemia mortality in boys and girls.

| BOYS | GIRLS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | Trend 4 | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | Trend 4 | ||||||||||||

| Period | APC | Period | APC | Period | APC | Period | APC | AAPC | Period | APC | Period | APC | Period | APC | Period | APC | AAPC | ||

| All cancers | |||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | 1979-1984 | 2.03 | 1985-94 | -3.08* | 1995-97 | 7.36 | 1998-08 | -0.59 | -0.34* | 1979-81 | 11.21 | 1982-1993 | -2.44* | 1994-98 | 4.77 | 1999-08 | -0.84 | -0.03 | |

| North | 1979-2008 | 2.09* | 2.09* | 1979-08 | 2.07* | 2.07* | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 1979-1983 | 10.09* | 1984-94 | -1.99* | 1995-98 | 12.65* | 1999-08 | 1.95* | 2.52* | 1979-82 | 13.23 | 1983-1988 | -5.51 | 1989-08 | 4.60* | 2.80* | |||

| Middle West | 1979-1984 | 13.07* | 1985-90 | -7.79 | 1991-08 | 0.25 | -0.70 | 1979-08 | -0.22 | -0.22 | |||||||||

| Southeast | 1979-1986 | 0.21 | 1987-93 | -4.75* | 1994-97 | 4.09 | 1998-08 | -2.06* | -1.41* | 1979-81 | 11.34 | 1982-1994 | -3.03* | 1995-98 | 5.73 | 1999-08 | -3.28* | -1.21* | |

| South | 1979-2008 | -1.57* | -1.57* | 1979-08 | -1.21* | -1.21* | |||||||||||||

| Leukemia | |||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | 1979-1984 | 4.01 | 1985-88 | -5.96 | 1989-08 | -0.55* | -0.98* | 1979-08 | -0.81* | -0.81* | |||||||||

| North | 1979-2008 | 2.02* | 2.02* | 1979-08 | 2.50* | 2.50* | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 1979-1983 | 18.36* | 1984-88 | -7.24 | 1989-08 | 2.73* | 1.75* | 1979-08 | 1.83* | 1.83* | |||||||||

| Middle West | 1979-2008 | -1.41* | -1.41* | 1979-08 | -0.86 | -0.86 | |||||||||||||

| Southeast | 1979-2008 | -2.12* | -2.12* | 1979-08 | -2.21* | -2.21* | |||||||||||||

| South | 1979-2008 | -2.45* | -2.45* | 1979-08 | -2.08* | -2.08* | |||||||||||||

APC indicates estimated annual percent change; AAPC, average annual percent change. * Significantly different from 0 (p<0.05).

A significant decline in leukemia of about 1% per year was observed in both genders (AAPC = −0.98 and -0.81 for boys and girls, respectively). Mortality due to childhood cancers declined over the entire period, with AAPCs of -1.41 for boys and -1.21 for girls in the Southeast and AAPCs of -1.57 for boys and -1.21 for girls in the South. The North (AAPC = +2.09 boys, +2.07 girls) and Northeast (AAPC = +2.52 boys, +2.80 girls) regions experienced significant increases of 2% per year in mortality rates. For leukemia, the same pattern of mortality decline occurred in the South and Southeast, but the mortality rates increased in the North and Northeast. A stable mortality rate was recorded in the Middle-West region except for boys, who experienced a significant decline for leukemia (AAPC -1.41).

Table 3 contains the AAMR data for all childhood cancers and for leukemia for 2006-2008. Similar mortality rates were recorded for all cancers among the five geographic regions of Brazil. The only difference was observed in some age groups among the regions; higher mortality rates were reported for the 0-year and 1-4-year groups in the Northeast and Middle West regions. Leukemia AAMRs were higher for boys in the North region (data not shown). During the first year of life, lower mortality rates were observed in the Southeast, while the mortality rate in the North was the highest.

Table 3.

Age-adjusted*) and crude (0-14 years) mortality rates for all cancers and leukemia by age group in Brazil and its regions (2006-2008) per million children.

| Age | Brazil | North | Northeast | Middle West | Southeast | South | ||

| All cancer | Specific rates | 0 | 40.43 | 33.59 | 49.55 | 45.13 | 36.60 | 32.60 |

| 1-4 | 40.09 | 39.33 | 41.24 | 46.09 | 38.14 | 40.39 | ||

| 5-9 | 36.61 | 30.34 | 34.86 | 36.95 | 39.15 | 37.86 | ||

| 10-14 | 36.17 | 34.93 | 35.45 | 38.25 | 34.71 | 41.71 | ||

| Rates per million | Crude | 37.62 | 34.49 | 37.68 | 40.35 | 37.21 | 39.52 | |

| *)Age-adjusted | 37.86 | 34.71 | 38.15 | 40.79 | 37.35 | 39.36 | ||

| Leukemia | Specific rates | 0 | 11.43 | 14.93 | 13.49 | 14.60 | 8.19 | 11.37 |

| 1-4 | 12.57 | 16.28 | 11.18 | 12.57 | 12.73 | 12.37 | ||

| 5-9 | 13.10 | 14.62 | 12.11 | 14.37 | 13.73 | 11.76 | ||

| 10-14 | 13.38 | 17.37 | 12.89 | 15.56 | 12.51 | 12.97 | ||

| Rates per million | Crude | 12.95 | 15.99 | 12.22 | 14.31 | 12.70 | 12.31 | |

| *)Age-adjusted | 12.89 | 15.96 | 12.15 | 14.18 | 12.64 | 12.27 |

World Standard Population, modified by Doll et al. (1966)

DISCUSSION

Childhood cancer mortality rates have decreased significantly in recent decades and have remained fairly constant since 1997 (11). Less-developed countries, including many countries in South America, have experienced less favorable outcomes. However, a major limitation of mortality rate analyses is the availability of high-quality vital statistics (1,12). Mortality rates should be analyzed with caution because they are affected by the quality of diagnosis data, quality of death certification, socioeconomic characteristics, and medical facilities specializing in pediatric oncology.

Since 1988, a complex health system (the Unified Health System) has been under development in Brazil and has substantially improved access to health care. Infant mortality decreased from 114 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to 19.3 per 1,000 live births in 2007 (13). Although the disparity is decreasing, geographic and social inequalities still exist; in the Northeast region, the infant mortality rate is 2.24 times higher than that in the South region (14). Pneumonia mortality for children aged 4 years and younger decreased significantly from 1991 to 2007 in all regions of Brazil, but the smallest decrease occurred in the North and Northeast regions in children younger than one year (15). Several initiatives have contributed to this decline, including promotion of breastfeeding, oral rehydration, and immunizations. Malnourishment in children less than 5 years old has significantly decreased in the past 17 years, from 7.1% to 1.8% for low-weight children and 19.6% to 6.8% for low-heightchildren (16). Vaccination reached universal coverage in the 1980s and is provided by the government. Poliomyelitis was eliminated from Brazil in 1989, and the last autochthonous case of measles occurred in 1999 (14).

Awareness of childhood cancer has increased since the 1980s, and several government and nongovernment initiatives have been implemented. In 1997, the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the Bank of Brazil Foundation together with the Brazilian Pediatric Oncology Society (SOBOPE) developed a program to promote early recognition of childhood cancer with better diagnostic procedures, better adherence to treatment protocols, and extensive pediatric oncology training. There has been a clear improvement in recognition and classification of leukemia with this approach (17). An early diagnosis program supported by a nongovernment organization was implemented in 2008. Its main objective is to train health family teams in the early recognition of signs and symptoms of cancer and to contribute to the organization of a network for referrals in various regions of the country.

Despite heterogeneity among the regions in Brazil, the AAMRs were similar from 2006-2008, and over 29 years, a slightly decreasing trend was observed in the Southeast and South regions. Several isolated institutions have significantly improved the treatment of childhood cancer. Following adherence to treatment protocols, children treated in specialized centers experienced a dramatic improvement in survival. In Recife, a city in the Northeast, a significant improvement in survival for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia was reported following the establishment of a twinning program (16). The Pediatric Department of the Hospital A. C. Camargo in São Paulo, an isolated specialized cancer center, analyzed 3,827 children and adolescents 0-18 years old with cancer and leukemia and reported a significant decrease in mortality rates from 1975-1999 (from 81% to 33%; p<0.001) (18). The Instituto Nacional de Câncer in Rio de Janeiro assessed 163 patients with rhabdomyosarcoma over 18 years and reported that 39.3% of the patients had metastatic disease at diagnosis, and the overall survival rates for clinical groups I+II, III, and IV were 79.6%, 68.3%, and 17.8%, respectively (p<0.001). Low weight (body mass index <10th percentile at diagnosis) emerged as an independent adverse prognostic factor (19).

Outcomes in children with cancer are much better following treatment by a multidisciplinary team in a pediatric cancer center (20,21). SOBOPE has established cooperative groups with planned clinical trials, which may potentially impact survival and mortality rates. The Brazilian Cooperative Group for Treatment of Childhood Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL) reported a 5-year overall survival of 92.5% among 544 children with low-risk ALL in several Brazilian centers (22). A recent study from the Osteosarcoma Brazilian Group indicated an overall survival of 60% for patients with nonmetastatic disease; a large tumor size was observed in 43% of the cases and was not associated with longer lag time (23). After the introduction of a standard protocol, the five-year overall survival for high-risk patients with germ-cell tumors was 83.3%, which is particularly relevant to the treatment protocols in small institutions with limited experience in the treatment of this rare disease (24).

An impressive decrease in mortality from ill-defined causes in all regions was observed from 1979-2008. The Mortality Information System was created in 1975 in Brazil, and since that time, steps have been taken to improve the quality of mortality data. In 2005, a thorough and careful supervision effort was performed to improve the quality of death certification in the Northeast and North. Fewer than 10% of ill-defined causes were recorded in the Southeast since 1979. This benchmark was reached in the South and Middle West regions in 1988 and in the Northeast and North in 2006. This change may underlie the documented increased cancer mortality rates in the North and Northeast regions. A consistent decrease in mortality rates due to childhood leukemia in Brazil and greater decreases in the South and Southeast were observed from 1980 to 2002. These decreases included a higher mortality rate for boys compared with girls, as confirmed by our data for 2006 to 2008. The leukemia mortality rate in the state of Rio de Janeiro declined during 1980 and 2006 and was also more pronounced in boys (25).

Correlations have been noted between social inequality and changes in mortality, with more pronounced decreases in mortality in the Brazilian regions with better socioeconomic conditions (5). Socioeconomic status plays a key role in health care due to factors such as access to health care services and specialized centers, availability of hospital beds, physician density, adherence and abandonment of treatment, early diagnosis, and clinician-parent communication. Despite improvements in childhood cancer survival in specialized centers, these improvements did not translate into a significant decline in mortality in Brazil or its regions. Socioeconomic inequalities may explain the divergence between hospital data and population-based registry data (26,27). According to a population-based registry study in São Paulo, the probability of survival for 60 months was 40% for patients 0-14 years of age with cancer (27).

The year 2006 may be considered a starting point for regional monitoring because quality control standards were achieved in the five geographic regions of Brazil and ill-defined deaths represented less than 10% of all deaths. During this period, the mortality rates were similar among all the regions, regardless of socioeconomic characteristics; the curves for the North and Northeast may still be climbing, or competitive risks of death may be masking mortality rates from cancer. The assessment period here was short, and longer periods will be necessary to evaluate comprehensive trends.

These observations need to be explored in further studies, including population-based cancer survival studies. Surveillance of childhood cancer mortality should be well maintained as a major resource for health planning and as a base to monitor the effectiveness of implemented strategies. Substantial challenges remain, and socioeconomic issues and adoption of integrated treatment strategies should be addressed to improve mortality rates due to childhood cancers in Brazil. This study is consistent with previous studies from Brazil showing that the magnitude of cancer mortality rates is generally lower than that observed in developed countries (28-30).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chatenoud L, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Levi F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Childhood cancer mortality in America, Asia, and Oceania, 1970 through 2007. Cancer. 2010;116(21):5063–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Negri E, Levi F, La Vecchia C. Childhood cancer mortality in Europe, 1970-2007. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(2):384–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Vecchia C, Levi F, Lucchini F, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Negri E. Trends in childhood cancer mortality as indicators of the quality of medical care in the developed world. Cancer. 1998;83(10):2223–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Lucchini F. Childhood cancer mortality in Europe, 1955-1995. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(6):785–809. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro KB, Lopes LF, De Camargo B. Trends in childhood leukemia mortality in Brazil and correlation with social inequalities. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1823–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.França E, de Abreu DX, Rao C, Lopez AD. Evaluation of cause-of-death statistic for Brazil, 2002-2004. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(4):891–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975. Vol 1, 9th rev. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. Vol 1, 10th rev. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doll R, Payne P, Waterhouse J, Cancer Incidence in Five Continents: A Technical Report 1966Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag (for UICC) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, Ries LAG, Melbert DL, O'Leary M, et al. Outcomes for Children and Adolescents With Cancer: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2625–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi F, Lavecchia C, Lucchini F, Negri E, Boyle P. Patterns of Childhood-Cancer Mortality - America, Asia and Oceania. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A(5):771–82. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00534-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. Health in Brazil 1 The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1778–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Victora CG, Aquino EML, Leal MD, Monteiro CA, Barros FC, Szwarcwald CL. Health in Brazil 2 Maternal and child health in Brazil: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(9780):1863–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues FE, Tatto RB, Vauchinski L, Leaes LM, Rodrigues MM, Rodrigues VB, et al. Pneumonia mortality in Brazilian children aged 4 years and younger. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2011;87(2):111–4. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pombo de Oliveira MS, Koifman S, Vasconcelos GM, Emerenciano M, de Oliveira Novaes C Brazilian Collaborative Study Group of Infant Acute Leukemia. Development and perspective of current Brazilian studies on the epidemiology of childhood leukemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2009;42(2):121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard SC, Pedrosa M, Lins M, Pedrosa A, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC, et al. Establishment of a pediatric oncology program and outcomes of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a resource-poor area. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2471–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Camargo B, Costa CML, Carvalho NS, Moreno M, Muradian M, Tanigutti P, et al. Decline in childhood cancer mortality in a tertiary hospital in Brazil: 1975-1999. SIOP XXXV MEETING—ABSTRACTS. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41(4):245–398. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferman SE, Land MGP, Eckhardt MBR. Survival analysis and body mass Index in pediatric patients with rhabdomyosarcoma: 18 years experience at the Brazilian National Cancer Institute. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2006;24(supplement 6):451. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meadows AT, Kramer S, Hopson R, Lustbader E, Jarrett P, Evans AE. Survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: effect of protocol and place of treatment. Cancer Invest. 1983;1(1):49–55. doi: 10.3109/07357908309040932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiller CA. Centralisation of treatment and survival rates for cancer. Arch Dis Chil. 1988;63(1):23–30. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandalise SR, Pinheiro VR, Aguiar SS, Matsuda EI, Otubo R, Yunes JA, et al. Benefits of the intermittent use of 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate in maintenance treatment for low-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: randomized trial from the Brazilian Childhood Cooperative Group--protocol ALL-99. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1911–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrilli AS, de Camargo B, Filho VO, Bruniera P, Brunetto AL, Jesus-Garcia R, et al. Brazilian Osteosarcoma Treatment Group Studies III and IV. Results of the Brazilian Osteosarcoma Treatment Group Studies III and IV: prognostic factors and impact on survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):1161–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes LF, Macedo CR, Pontes EM, Dos Santos Aguiar S, Mastellaro MJ, Melaragno R, et al. Cisplatin and etoposide in childhood germ cell tumor: brazilian pediatric oncology society protocol GCT-91. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1297–303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couto AC, Ferreira JD, Koifman RJ, Monteiro GT, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS, Koifman S. Trends in childhood leukemia mortality over a 25-year period. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;86(5):405–10. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braga PE, Latorre Md Mdo R, Curado MP. Childhood cancer: a comparative analysis of incidence, mortality, and survival in Goiania (Brazil) and other countries. Cad Saude Publica. 2002;18(1):33–44. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2002000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirra AP, Latorre MRDO, Veneziano DB. Incidência, Mortalidade e sobrevida do Câncer na infância no Município de São Paulo. Registro de Câncer de São Paulo. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatenoud L, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Levi F, Curado MP, Malvezzi M, et al. Trends in cancer mortality in Brazil, 1980-2004. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2010;19(2):79–86. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833233be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonseca LAM, Eluf-Neto J, Wunsch Filho V. Cancer mortality trends in Brazilian state capitals, 1980-2004. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56(3):309–12. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azevedo e Silva G, Gamarra JC, Girianelli VR, Valente JG. Cancer mortality trends in Brazilian state capitals and other municipalities between 1980 and 2006. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(6):1–9. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011005000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]