Abstract

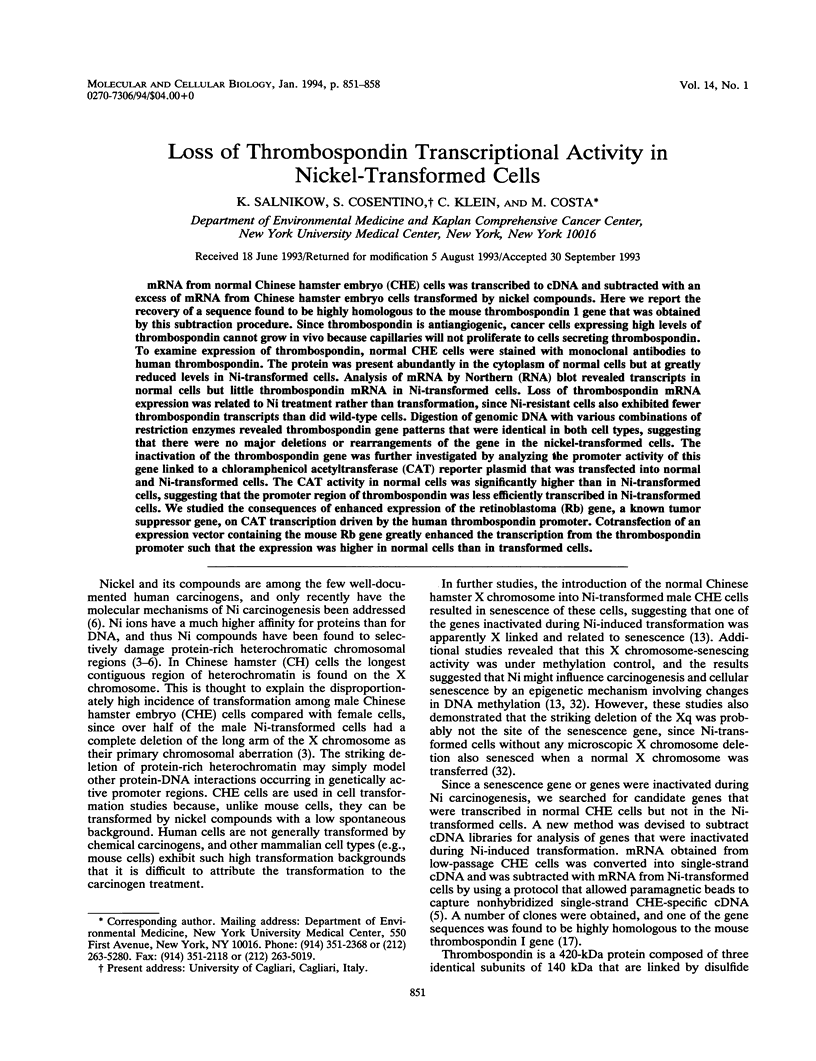

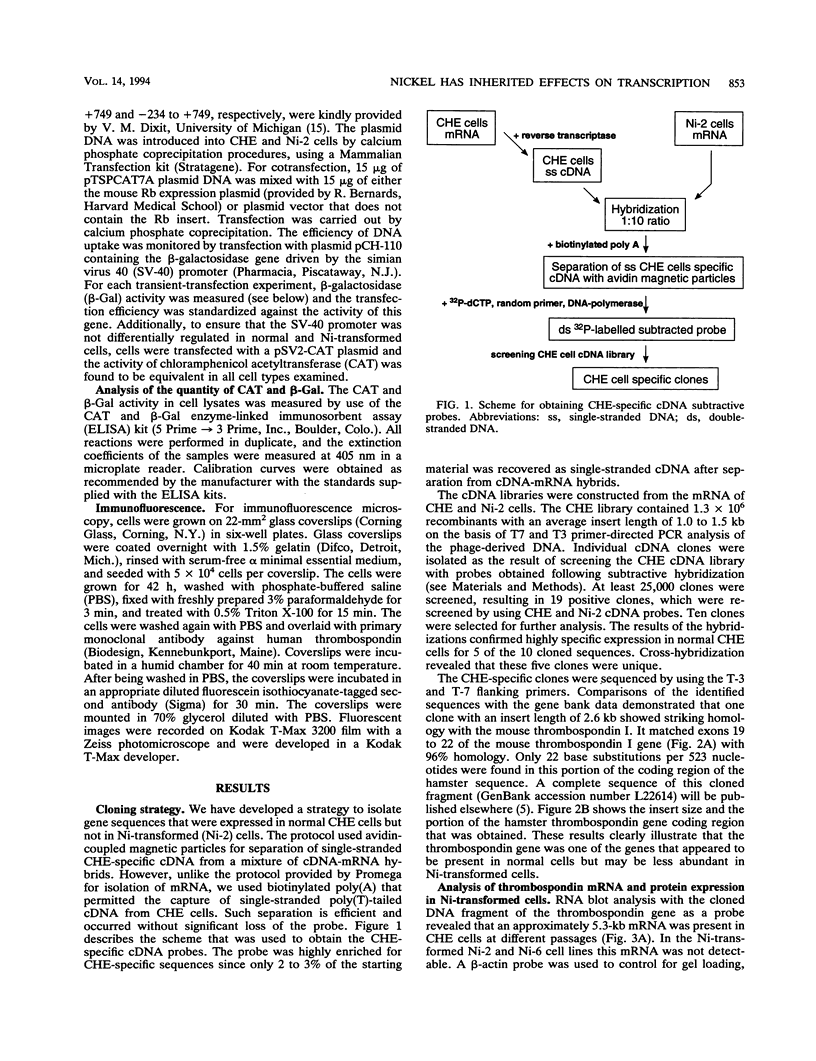

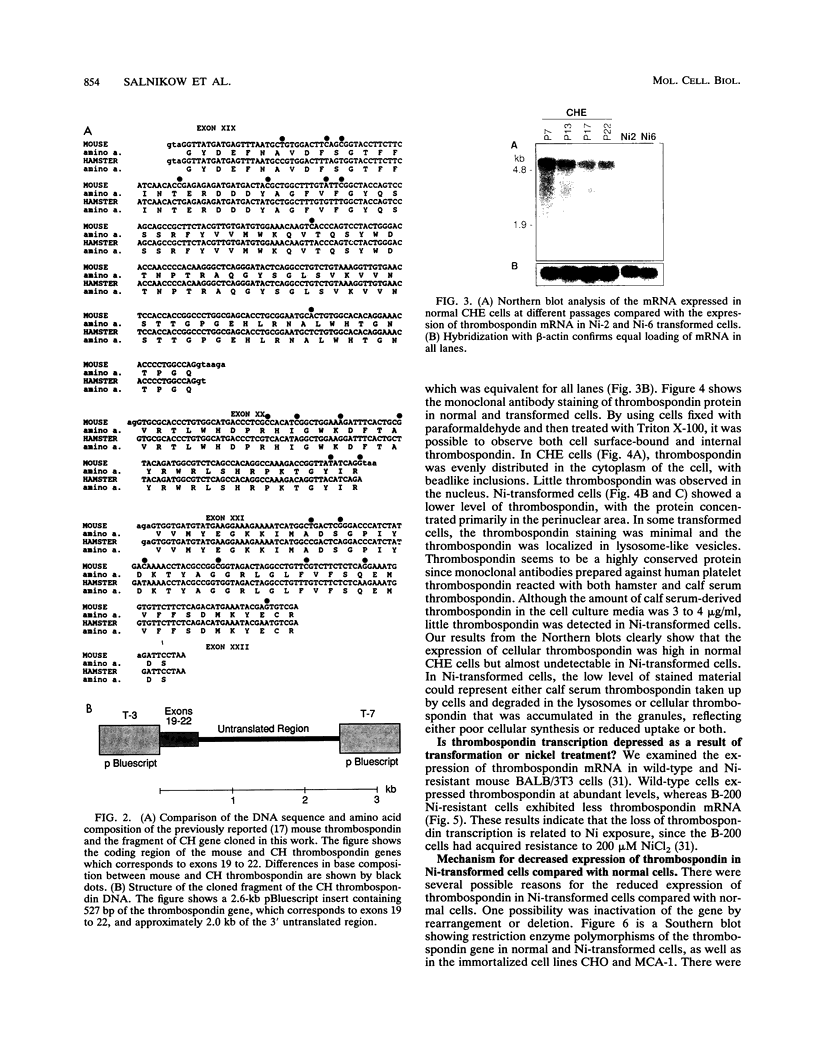

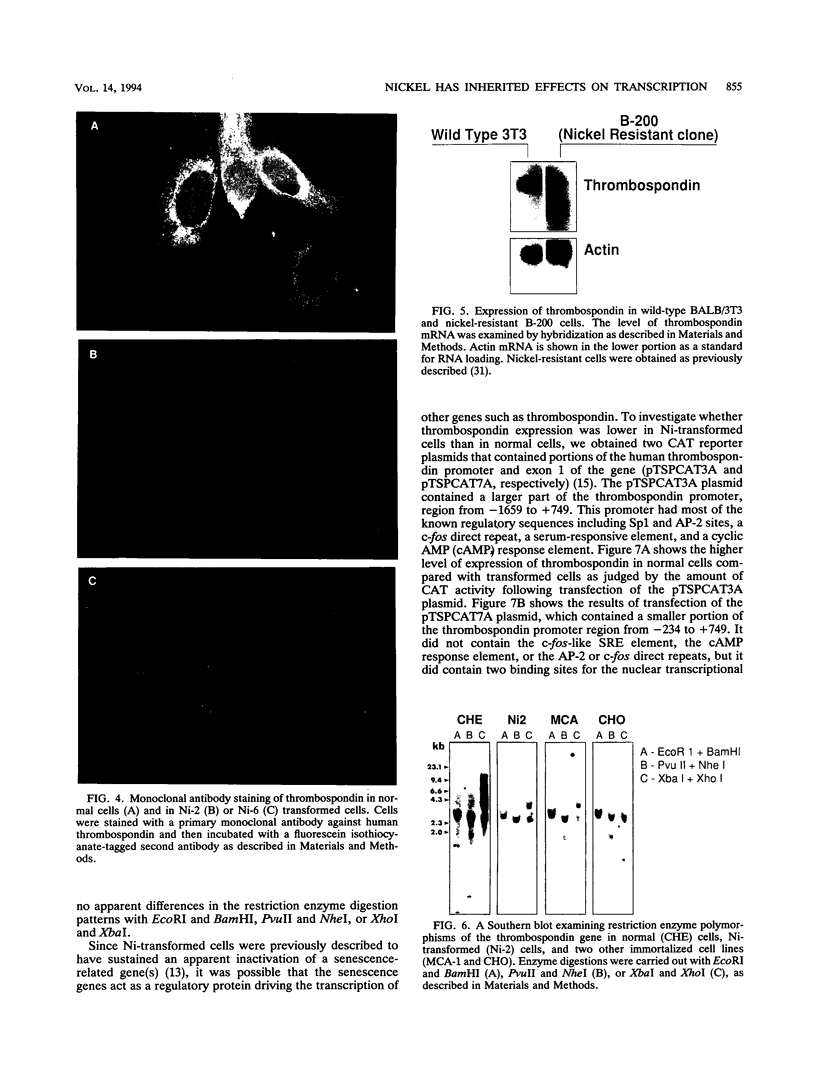

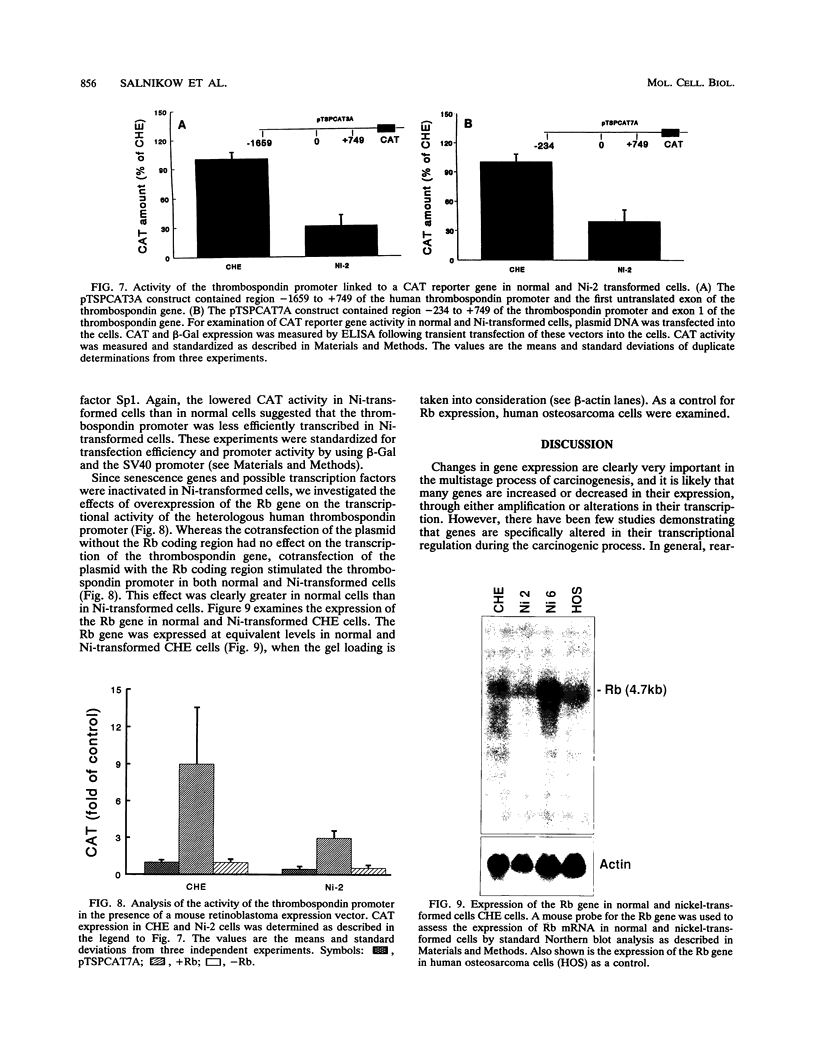

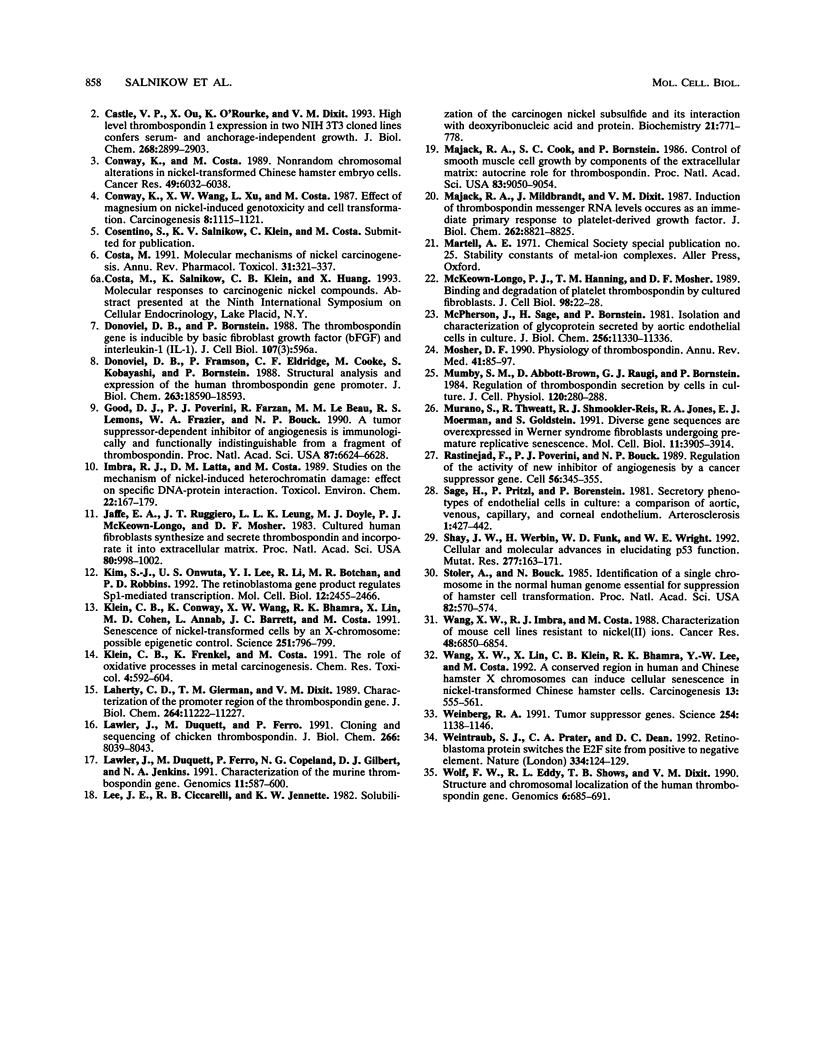

mRNA from normal Chinese hamster embryo (CHE) cells was transcribed to cDNA and subtracted with an excess of mRNA from Chinese hamster embryo cells transformed by nickel compounds. Here we report the recovery of a sequence found to be highly homologous to the mouse thrombospondin 1 gene that was obtained by this subtraction procedure. Since thrombospondin is antiangiogenic, cancer cells expressing high levels of thrombospondin cannot grow in vivo because capillaries will not proliferate to cells secreting thrombospondin. To examine expression of thrombospondin, normal CHE cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies to human thrombospondin. The protein was present abundantly in the cytoplasm of normal cells but at greatly reduced levels in Ni-transformed cells. Analysis of mRNA by Northern (RNA) blot revealed transcripts in normal cells but little thrombospondin mRNA in Ni-transformed cells. Loss of thrombospondin mRNA expression was related to Ni treatment rather than transformation, since Ni-resistant cells also exhibited fewer thrombospondin transcripts than did wild-type cells. Digestion of genomic DNA with various combinations of restriction enzymes revealed thrombospondin gene patterns that were identical in both cell types, suggesting that there were no major deletions or rearrangements of the gene in the nickel-transformed cells. The inactivation of the thrombospondin gene was further investigated by analyzing the promoter activity of this gene linked to a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter plasmid that was transfected into normal and Ni-transformed cells. The CAT activity in normal cells was significantly higher than in Ni-transformed cells, suggesting that the promoter region of thrombospondin was less efficiently transcribed in Ni-transformed cells. We studied the consequences of enhanced expression of the retinoblastoma (Rb) gene, a known tumor suppressor gene, on CAT transcription driven by the human thrombospondin promoter. Cotransfection of an expression vector containing the mouse Rb gene greatly enhanced the transcription from the thrombospondin promoter such that the expression was higher in normal cells than in transformed cells.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Castle V. P., Ou X., O'Rourke K., Dixit V. M. High level thrombospondin 1 expression in two NIH 3T3 cloned lines confers serum- and anchorage-independent growth. J Biol Chem. 1993 Feb 5;268(4):2899–2903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway K., Costa M. Nonrandom chromosomal alterations in nickel-transformed Chinese hamster embryo cells. Cancer Res. 1989 Nov 1;49(21):6032–6038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway K., Wang X. W., Xu L. S., Costa M. Effect of magnesium on nickel-induced genotoxicity and cell transformation. Carcinogenesis. 1987 Aug;8(8):1115–1121. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.8.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. Molecular mechanisms of nickel carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991;31:321–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.31.040191.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoviel D. B., Framson P., Eldridge C. F., Cooke M., Kobayashi S., Bornstein P. Structural analysis and expression of the human thrombospondin gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1988 Dec 15;263(35):18590–18593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good D. J., Polverini P. J., Rastinejad F., Le Beau M. M., Lemons R. S., Frazier W. A., Bouck N. P. A tumor suppressor-dependent inhibitor of angiogenesis is immunologically and functionally indistinguishable from a fragment of thrombospondin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(17):6624–6628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe E. A., Ruggiero J. T., Leung L. K., Doyle M. J., McKeown-Longo P. J., Mosher D. F. Cultured human fibroblasts synthesize and secrete thrombospondin and incorporate it into extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Feb;80(4):998–1002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J., Onwuta U. S., Lee Y. I., Li R., Botchan M. R., Robbins P. D. The retinoblastoma gene product regulates Sp1-mediated transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Jun;12(6):2455–2463. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C. B., Conway K., Wang X. W., Bhamra R. K., Lin X. H., Cohen M. D., Annab L., Barrett J. C., Costa M. Senescence of nickel-transformed cells by an X chromosome: possible epigenetic control. Science. 1991 Feb 15;251(4995):796–799. doi: 10.1126/science.1990442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C. B., Frenkel K., Costa M. The role of oxidative processes in metal carcinogenesis. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991 Nov-Dec;4(6):592–604. doi: 10.1021/tx00024a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laherty C. D., Gierman T. M., Dixit V. M. Characterization of the promoter region of the human thrombospondin gene. DNA sequences within the first intron increase transcription. J Biol Chem. 1989 Jul 5;264(19):11222–11227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J., Duquette M., Ferro P. Cloning and sequencing of chicken thrombospondin. J Biol Chem. 1991 May 5;266(13):8039–8043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J., Duquette M., Ferro P., Copeland N. G., Gilbert D. J., Jenkins N. A. Characterization of the murine thrombospondin gene. Genomics. 1991 Nov;11(3):587–600. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. E., Ciccarelli R. B., Jennette K. W. Solubilization of the carcinogen nickel subsulfide and its interaction with deoxyribonucleic acid and protein. Biochemistry. 1982 Feb 16;21(4):771–778. doi: 10.1021/bi00533a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majack R. A., Cook S. C., Bornstein P. Control of smooth muscle cell growth by components of the extracellular matrix: autocrine role for thrombospondin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Dec;83(23):9050–9054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majack R. A., Mildbrandt J., Dixit V. M. Induction of thrombospondin messenger RNA levels occurs as an immediate primary response to platelet-derived growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jun 25;262(18):8821–8825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo P. J., Hanning R., Mosher D. F. Binding and degradation of platelet thrombospondin by cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1984 Jan;98(1):22–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson J., Sage H., Bornstein P. Isolation and characterization of a glycoprotein secreted by aortic endothelial cells in culture. Apparent identity with platelet thrombospondin. J Biol Chem. 1981 Nov 10;256(21):11330–11336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher D. F. Physiology of thrombospondin. Annu Rev Med. 1990;41:85–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.41.020190.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby S. M., Abbott-Brown D., Raugi G. J., Bornstein P. Regulation of thrombospondin secretion by cells in culture. J Cell Physiol. 1984 Sep;120(3):280–288. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murano S., Thweatt R., Shmookler Reis R. J., Jones R. A., Moerman E. J., Goldstein S. Diverse gene sequences are overexpressed in werner syndrome fibroblasts undergoing premature replicative senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Aug;11(8):3905–3914. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastinejad F., Polverini P. J., Bouck N. P. Regulation of the activity of a new inhibitor of angiogenesis by a cancer suppressor gene. Cell. 1989 Feb 10;56(3):345–355. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage H., Pritzl P., Bornstein P. Secretory phenotypes of endothelial cells in culture: comparison of aortic, venous, capillary, and corneal endothelium. Arteriosclerosis. 1981 Nov-Dec;1(6):427–442. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.1.6.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay J. W., Werbin H., Funk W. D., Wright W. E. Cellular and molecular advances in elucidating p53 function. Mutat Res. 1992 Aug;277(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(92)90003-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoler A., Bouck N. Identification of a single chromosome in the normal human genome essential for suppression of hamster cell transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(2):570–574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. W., Imbra R. J., Costa M. Characterization of mouse cell lines resistant to nickel(II) ions. Cancer Res. 1988 Dec 1;48(23):6850–6854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. W., Lin X., Klein C. B., Bhamra R. K., Lee Y. W., Costa M. A conserved region in human and Chinese hamster X chromosomes can induce cellular senescence of nickel-transformed Chinese hamster cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 1992 Apr;13(4):555–561. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg R. A. Tumor suppressor genes. Science. 1991 Nov 22;254(5035):1138–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1659741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf F. W., Eddy R. L., Shows T. B., Dixit V. M. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human thrombospondin gene. Genomics. 1990 Apr;6(4):685–691. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90505-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]