Abstract

Purpose

Prospective studies suggest that statins protect against advanced stage and possibly high grade prostate cancer. However, few studies have investigated the influence of stains on outcomes in men with prostate cancer. Thus, we evaluated the association of statin use with pathological tumor characteristics and prostate cancer recurrence after prostatectomy in a retrospective cohort.

Materials and Methods

A total of 2,399 patients of 1 surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital who underwent radical prostatectomy in 1993 to 2006 and had not previously received hormone or radiation therapy were followed for recurrence. The surgeon routinely asked during the preoperative consultation what medications the men were using. Additional information on statin use was obtained from a mailed survey. We estimated the association of statin use with nonorgan confined disease (pT3a/b or N1) and high grade disease (Gleason sum [4 + 3] or greater) using logistic regression (OR), and recurrence using Cox proportional hazards regression (HR).

Results

The 16.1% of men who used a statin at prostatectomy were statistically significantly less likely to have nonorgan confined disease than nonusers (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.85). Statin use was inversely associated with high grade disease only in men with preoperative PSA 10 ng/ml or greater (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13–0.93, p-interaction = 0.02). The HR of recurrence among men who used a statin for 1 year or greater compared to nonusers was 0.77 (95% CI 0.41–1.42).

Conclusions

Our findings support the hypothesis that statin use may protect against prostate cancer with poorer pathological characteristics. We could not rule in or out that longer term statin use may protect against recurrence after prostatectomy.

Keywords: prostate, prostatic neoplasms, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, prostatectomy, neoplasm recurrence, local

Prospective studies support the hypothesis that statin drugs protect against the development of advanced stage and possibly high grade prostate cancer,1-6 although results are generally null for prostate cancer overall.2,4-11 Few studies have examined the influence of statins on pathological characteristics of prostate cancers12,13 and recurrence after treatment.14-19 A retrospective study in 250 patients reported that statins were associated with more favorable pathological characteristics, but this association did not persist after adjustment.12 A larger study in 1,351 patients found that statin users had more favorable pathological characteristics than nonusers.13 Studies addressing statin use and recurrence have reported conflicting results. One reported a nonsignificant inverse association in men who underwent brachytherapy.15 Three studies examined outcomes after radiotherapy, of which 2 reported an inverse association,14,18 but the third reported no association.16 One of the 2 studies that examined the association between statin use and recurrence after surgical treatment found an inverse association,17 whereas the other found no association.19

Additional investigations on whether statins influence prostate tumor extent or morphology may inform whether statins prevent advanced stage or high grade prostate cancer. Further, additional investigations on whether statins influence recurrence after prostate cancer treatment may inform whether these drugs have utility as adjuvant therapy for men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Thus, we evaluated the association of statin use with pathological characteristics and recurrence after prostatectomy in a retrospective cohort.

METHODS

Study Population

A total of 2,498 patients with clinically localized prostate cancer who underwent radical retropubic prostatectomy performed by the same surgeon at the Johns Hopkins Hospital between January 1, 1993 and March 31, 2006 were followed for recurrence. At the preoperative consultation the surgeon asked if the men were currently using any medications. If yes, he recorded in the medical record the type of medication, and if no, he recorded that none was used. Preoperative PSA concentration was measured by the surgeon or, since 2004, obtained from the medical record provided by the referring urologist. Preoperative PSA velocity was calculated based on multiple PSA tests from the medical record provided by the referring urologist.

We excluded 2.8% of the men from analysis because of missing information on medication use. Of the men 1.2% were excluded since they received hormone or radiation therapy before prostatectomy. After these exclusions 2,399 men remained in the study cohort. Median followup was 7 years and the proportion of total possible followup observed was 76%. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Assessment

Statin use

Medical records for the preoperative consultation were reviewed and information on all medications used, including statins, aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACE inhibitors, α-adrenergic blockers, and diabetes medications, was abstracted while blinded to the outcome. Drug dose was not available.

Information on the timing and duration of statin use was obtained from a survey on lifestyle and medical factors mailed to the 2,209 men who were alive and residing in the United States as of November 2007. Of the 2,399 men 1.8% died before the surveys were mailed. The men were asked whether they had used a statin before or after prostatectomy and, if so, for how long (less than 1, 1 to 4, 5 to 9, or 10 years or greater). Of the 2,209 eligible men 1,583 (72%) responded by August 2009 and were included in analysis. When statin use reported on the survey conflicted with information from the preoperative consultation (8% of cases), we used the information from the preoperative consultation.

Outcome

Prostatectomy specimens were evaluated uniformly by a small number of genitourinary pathologists at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. We classified 683 men with extraprostatic extension (pT3a), seminal vesicle invasion (pT3b), or lymph node involvement (N1) as having nonorgan confined disease, and 242 with a Gleason sum of (4 + 3) or greater as having high grade disease.

Men who underwent prostatectomy were followed postoperatively with PSA tests and digital rectal examinations every 3 months for the first year, semiannually for the second year, and annually thereafter by their primary care physicians. The surgeon contacted the men by mail yearly to request that their physician send their most recent PSA test results for assessment of biochemical recurrence. If PSA was increased, the surgeon repeated a PSA test and recommended imaging as necessary. PSA information 1 year after surgery was available for 99% of the men, and by 5 years of followup PSA information was complete for 80%. Prostate cancer deaths were ascertained through the National Death Index. We classified the 247 men who experienced a confirmed repeat PSA increase from a nadir of nondetectable to 0.2 ng/ml or greater, including biochemical recurrence in 177, local recurrence in 5, metastasis in 46, and prostate cancer death in 9, as having recurred. A total of 55 men died of any cause.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated age standardized means and proportions by statin use at prostatectomy. On cross-sectional analyses, we used logistic regression to calculate age and multivariable adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of nonorgan confined (vs pathologically organ confined), high grade (vs low grade) prostate cancer, and PSA 10 ng/ml or greater (vs less than 10 ng/ml), comparing men who used a statin at the time of the preoperative consultation with nonusers. We repeated this analysis for the duration of statin use before prostatectomy using information from the survey. Covariates obtained from the preoperative consultation medical record were included in the models if they were associated with pathological characteristics or statin use, including age, race, first degree family history of prostate cancer, BMI, aspirin use, and ACE inhibitor use. We further adjusted for cigarette smoking assessed on the survey. Stage and grade were analyzed, stratifying by preoperative PSA (less than 10 vs 10 ng/ml or greater), age at prostatectomy (less than 60 vs 60 years or greater), BMI (less than 26 vs 26 kg/m2 or greater), number of preoperative PSA tests (less than 1 vs 1 or greater), and use of aspirin or ACE inhibitors at prostatectomy (yes vs no). Statistical interaction was evaluated using the likelihood ratio test.

Using the retrospective cohort design, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate age and multivariable adjusted cause specific HRs and 95% CIs of recurrence and of progression to metastasis or prostate cancer death. For recurrence, we began followup at prostatectomy and censored men at the date of documented recurrence, death or last contact between surgeon and patient, whichever occurred earliest. Similarly, for progression to metastasis or prostate cancer death, we censored men at metastasis, death, or last followup. We estimated the HR of recurrence for statin use at prostatectomy (vs nonuse). Among men who responded to the survey, we estimated the HRs of recurrence for ever statin use before surgery (vs nonuse), time dependent statin use after surgery (vs nonuse), and time dependent total duration of statin use (vs nonuse). Covariates obtained from the medical record were included in the models if they were associated with either recurrence or statin use, including age, race, family history of prostate cancer, BMI, use of aspirin or an ACE inhibitor at the time of the preoperative consultation, pathological stage, pathological Gleason sum, preoperative PSA, and surgery calendar year. We also adjusted for cigarette smoking, which was assessed on the survey. We confirmed the proportional hazards assumption.

All analyses were done using SAS®, version 9.1. All tests were 2-sided and results were considered statistically significant at p <0.05.

RESULTS

At prostatectomy, 16.1% of the men used a statin. Compared with nonusers, statin users were older and more likely to use aspirin and ACE inhibitors, had lower preoperative PSA, and underwent surgery more recently (table 1). Median time from biopsy to prostatectomy was similar between statin users and nonusers. Characteristics were adjusted to the age distribution of the entire cohort (table 1).

Table 1.

Age adjusted characteristics of Johns Hopkins Hospital prostatectomy cohort by statin use at prostatectomy from 1993 to 2006

| No Statin | Statin | p Value (Wald test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| No. pts (%) | 2,012 (83.9) | 386 (16.1) | |

| Mean age | 56.0 | 57.7 | <0.0001 |

| % Race: | |||

| White | 92.4 | 93.0 | 0.58 |

| Black | 3.0 | 1.4 | |

| Asian | 0.7 | 0.9 | |

| Other/missing | 3.9 | 4.6 | |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 | 26.7 | 0.06 |

| Mean ht (inches) | 70.6 | 70.6 | 0.48 |

| % Cigarette smoking: | |||

| Never | 33.4 | 34.0 | 0.28 |

| Current | 1.5 | 1.0 | |

| Former | 27.5 | 31.5 | |

| Missing | 37.5 | 33.6 | |

| % Prostate Ca family history | 23.4 | 28.2 | 0.06 |

| % Aspirin use | 7.5 | 19.5 | <0.0001 |

| % ACE inhibitor use | 7.3 | 15.7 | <0.0001 |

| Mean days biopsy-surgery | 112 | 112 | 0.87 |

| Mean surgery yr | 1998 | 2000 | <0.0001 |

| Mean yrs from surgery to recurrence* | 4.1 | 4.0 | 0.44 |

| Preop | |||

| % Stage: | |||

| T1a–T1b | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| T1c | 67.0 | 73.0 | |

| T2a–T2c | 31.5 | 25.4 | |

| T3a | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| % Gleason sum: | |||

| 6 or Less | 81.9 | 80.0 | |

| 7 (less than 4+3) | 12.1 | 13.1 | |

| 7 (4 or greater + 3) | 5.8 | 6.6 | 0.72 |

| Mean PSA (ng/ml) | 7.1 | 6.3 | 0.004 |

| No. PSA tests | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.07 |

| Mean PSA velocity (ng/ml/yr) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.53 |

| Postop | |||

| % Stage: | |||

| Organ confined | 77.9 | 83.3 | |

| Extraprostatic extension | 16.4 | 12.8 | |

| Seminal vesicle invasion or worse | 4.0 | 2.3 | 0.04 |

| % Gleason sum: | |||

| 6 or Less | 68.1 | 70.5 | |

| Less than 7 (4 + 3) | 21.4 | 20.5 | |

| 7 or Greater (4 + 3) | 10.3 | 9.0 | 0.67 |

| % Pos surgical margins | 8.1 | 6.1 | 0.11 |

| Mean PSA doubling time (mos) | 12.8 | 12.4 | 0.28 |

In 247 men with recurrence.

Pathological Characteristics

After age and multivariable adjustment, statin use at prostatectomy was inversely associated with nonorgan confined disease (table 2). The association did not differ by duration of use among survey respondents (data not shown). The association for statin use at prostatectomy was unchanged after excluding men with positive surgical margins, men who used an α-adrenergic blocker or diabetes medications, or nonwhite men (each p <0.05). Further adjustment for drugs for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and psychiatric diagnoses, comorbid conditions, number of preoperative PSA tests, preoperative PSA concentration, PSA velocity, or calendar year did not alter the results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Pathological tumor characteristics and statin use at prostatectomy in Johns Hopkins Hospital prostatectomy cohort from 1993 to 2006

| No. Statin Users/Total No. | OR (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Adjusted | Adjusted* | ||

| Nonorgan confined disease: | |||

| No | 294/1,716 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Yes | 92/683 | 0.70 (0.54–0.90) | 0.66 (0.50–0.85)† |

| Gleason sum: | |||

| Less than (4 + 3) | 348/2,157 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| (4 + 3) or Greater | 38/242 | 0.88 (0.61–1.27) | 0.85 (0.58–1.23) |

| Preop PSA (ng/ml): | |||

| Less than 10 | 336/2,003 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 10 or Greater | 50/396 | 0.69 (0.50–0.94) | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) |

Adjusted for age (years, continuous), race (black, white or other/missing), BMI (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, 30 kg/m2 or greater, or missing), smoking status (no, yes or missing), prostate cancer family history (no, yes or missing), aspirin use (no or yes), and ACE inhibitor use (no or yes) at prostatectomy.

Restricting to surgery calendar years 1996 to 2006 and adjusted for calendar year in 3 categories (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51–0.94).

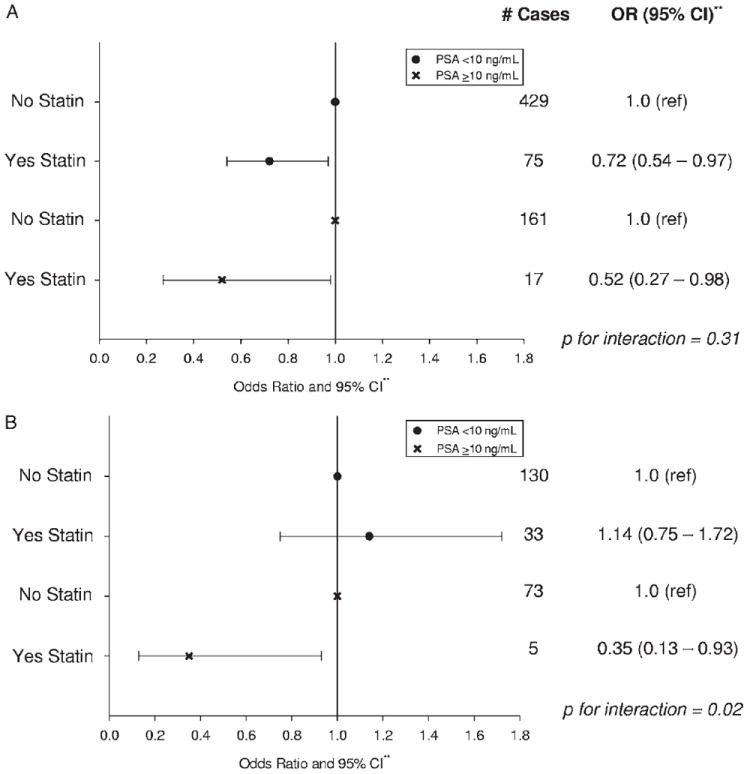

Statin use at prostatectomy was not inversely associated with high grade disease (table 2), except among men with a preoperative PSA concentration of 10 ng/ml or greater (p-interaction = 0.02, part B of figure). When restricting to men with organ confined disease, the results for high grade disease overall were unchanged, and they were also unchanged when stratified by preoperative PSA. Statin use was inversely associated with nonorgan confined disease in men with preoperative PSA less than 10 and 10 ng/ml or greater (part A of figure). Statin use was inversely associated with higher preoperative PSA (table 2).

Association between pathological tumor characteristics and statin use at prostatectomy by preoperative PSA in Johns Hopkins Hospital prostatectomy cohort from 1993 to 2006. All prostatectomies were done by same surgeon. A, nonorgan confined vs organ confined disease. B, Gleason sum 4 + 3 or greater vs less than 4 + 3. Asterisks indicate adjusted for age, race, BMI, smoking status, family history, aspirin use, and ACE inhibitor use at prostatectomy.

Statin use was inversely associated with nonorgan confined disease regardless of age at surgery (less than 60 years OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.51–1.02 and 60 years or greater OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39 – 0.86). Statin use appeared to be inversely associated with high grade disease in men less than 60 years old (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.29 –1.04), but not in men 60 years old or older (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.71–1.86, p-interaction = 0.06). BMI did not modify the association between statin use and nonorgan confined (p-interaction = 0.88) or high grade (p-interaction = 0.67) disease. Statin use was inversely associated with nonorgan confined disease among men who did not use aspirin (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.44 – 0.80), but not among aspirin users (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.70 –1.83, p-interaction = 0.13). In contrast, statin use appeared to be inversely associated with high grade disease in aspirin users (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.27–1.48), but not in nonusers (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.66 –1.48, p-interaction = 0.09). ACE inhibitor use did not modify the association between statin use and nonorgan confined (p-interaction = 0.14) or high grade (p-interaction = 0.22) disease. The association between statin use and nonorgan confined disease (p-interaction = 0.50), and with high grade disease (p-interaction = 0.91) was similar by the number of preoperative PSA tests.

Recurrence

Compared with nonuse, statin use at prostatectomy was not associated with recurrence (HR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.67–1.49), or with progression to metastasis or death (HR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.38–1.92). Among survey respondents, 16.6% (263) were on a statin at prostatectomy. Of these men 39.0% (516) began receiving a statin subsequently. Ever use of a statin irrespective of starting before or after surgery (vs never use) (table 3), ever use before surgery (vs never use before surgery and adjusting for ever use after prostatectomy), and first (vs never) or ever use after surgery (vs never use after surgery and adjusting for ever use before surgery) were not associated with recurrence (data not shown). The HR of recurrence for men who used a statin for 1 year or greater irrespective of whether use began before or after prostatectomy compared with never users was 0.77 (95% CI 0.41–1.42). The HR of biochemical recurrence alone was 0.82 (95% CI 0.42–1.64). We could not rule out a positive association for men who used a statin for less than 1 year (table 3). These results were similar after excluding men with positive surgical margins (data not shown).

Table 3.

Statin use and recurrence after prostatectomy in 1,583 men (74%) who responded to survey in Johns Hopkins Hospital prostatectomy cohort from 1993 to 2006

| Time Dependent Statin Use | No. Recurrences/No. Person-Years | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 86/7,266 | 1.00 (referent) |

| Ever (yrs): | 41/3,889 | 0.99 (0.64–1.55) |

| Less than 1 | 7/445 | 2.42 (0.94–6.24) |

| 1 or Greater | 27/3,444 | 0.77 (0.41–1.42) |

Adjusted for age (years, continuous), race (black, white or other/missing), BMI (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, 30 kg/m2 or greater, or missing), smoking (never, current, former or missing), prostate cancer family history (no, yes or missing), aspirin use (no or yes), and ACE inhibitor use (no or yes) at prostatectomy, surgery calendar year (continuous), preoperative PSA (continuous), pathological stage (nonorgan confined or organ confined disease) and Gleason sum (less than 4 + 3, or 4 + 3 or greater).

DISCUSSION

In this cohort, we observed that men who used a statin at prostatectomy were less likely to have nonorgan confined disease than nonusers. Among men with higher preoperative PSA, statin users were less likely to have high grade disease. Our findings for pathological characteristics are compatible with those from cohort studies showing an inverse association of statin use with the risk of advanced stage and high grade prostate cancer.1-6 We could not rule in or out that longer term statin use may protect against recurrence after prostatectomy.

Other groups have reviewed the biological plausibility that statins influence prostate cancer incidence or recurrence.20,21 Statin drugs, which inhibit cholesterol synthesis, may influence prostate carcinogenesis through their effects on cholesterol sensitive pathways such as Akt or through their anti-inflammatory properties. Despite the biological plausibility, few studies have investigated the association of statins with pathological characteristics and risk of recurrence. For the pathological characteristics, our results differ from those from 1 small study,12 but are consistent with those from a later, larger study.13 For recurrence, our results are consistent with 4 published studies,14,15,17,18 but not with the other report.16

Although overall we saw no association between statin use and high grade disease, among men with high preoperative PSA, those who were on a statin were less likely to have a high grade cancer, although this finding is based on a small number of cases. An explanation for this observation is that statins prevent prostate cancer with a poorer prognosis. Preoperative PSA is a prognostic indicator, so that men with both high preoperative PSA and high pathological Gleason sum may have a more aggressive tumor than men with low preoperative PSA and high Gleason sum.22 These results were not explained by men with high preoperative PSA and high grade disease also having nonorgan confined disease.

Strengths and Limitations

Our large sample size to assess main effects, uniform pathology assessment, and recording of statin use at surgery are study strengths. Detection bias due to different PSA screening histories by statin use is unlikely. Users and nonusers had similar numbers of preoperative PSA tests and median times from biopsy to prostatectomy, suggesting comparable provision and utilization of care between the 2 groups. We observed no difference in the association of statin use with nonorgan confined and high grade disease by the number of preoperative PSA tests further arguing against detection bias. More research is needed to determine if statins may influence risk differently in men with different preoperative characteristics or race/ethnicities. Patients in this cohort were younger than the median age at diagnosis in the United States, and most were white. We were unable to address whether different types or doses of statins may influence prostate cancer pathology and recurrence differently because information on dose and type of statin was not available.

Of the eligible men 75% responded to the mailed survey. Compared with respondents, nonrespondents were less likely to have received a statin at surgery (14.0% vs 16.6%, p = 0.08), likely to have undergone surgery earlier (mean 1998 vs 1999, p <0.0001), and more likely to have experienced recurrence (actuarial 19% vs 14%, p <0.0001). These small differences make profound selection bias unlikely. Further, the association between statin use at surgery and prostate cancer recurrence did not differ between men who did and did not return the survey (p-interaction = 0.65). We assessed self-reported statin use, which may be subject to imperfect recall. We had 80% power at α = 0.05 to detect an HR of 0.6 or less, a magnitude similar to associations observed between statin use and the incidence of advanced prostate cancer in previous studies. Thus, our null result for the association between statin use at prostatectomy and recurrence is likely not due to insufficient power. Finally, we cannot rule out residual confounding due to imperfect adjustment for pathological stage and grade on recurrence analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results support the hypothesis that statins may protect against the development of prostate cancer with poorer pathological characteristics. We could not rule in or out that longer term statin use may protect against recurrence after prostatectomy. If borne out in other studies, these findings could have important implications for prostate cancer chemoprevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

Study received approval from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health institutional review boards.

Supported by National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award T32 CA009314 (AMM) and Public Health Service Research Grant P50 CA58236 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- BMI

body mass index

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

References

- 1.Shannon J, Tewoderos S, Garzotto M, et al. Statins and prostate cancer risk: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Visvanathan K, et al. Statin drugs and risk of advanced prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1819. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flick ED, Habel LA, Chan KA, et al. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer in the California Men’s Health Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2218. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs EJ, Rodriguez C, Bain EB, et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs and advanced prostate cancer incidence in a large U.S. cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2213. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtola TJ, Tammela TL, Lahtela J, et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs and prostate cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2226. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman GD, Flick ED, Udaltsova N, et al. Screening statins for possible carcinogenic risk: up to 9 years of follow-up of 361 859 recipients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:27. doi: 10.1002/pds.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agalliu I, Salinas CA, Hansten PD, et al. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer: results from a population-based epidemiologic study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:250. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudreau DM, Yu O, Buist DS, et al. Statin use and prostate cancer risk in a large population-based setting. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:767. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9139-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Strom BL. Statin use and the risk of 10 cancers. Epidemiology. 2007;18:213. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000254694.03027.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friis S, Poulsen AH, Johnsen SP, et al. Cancer risk among statin users: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:643. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye JA, Jick H. Statin use and cancer risk in the General Practice Research Database. B Br J Cancer. 2004;90:635. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rijo Mora E, Lorente Garin JA, Bielsa Gali O, et al. The impact of statins use in clinically localized prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33:351. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(09)74159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeb S, Kan D, Helfand BT, et al. Is statin use associated with prostate cancer aggressiveness? BJU Int. 2009;105:1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutt R, Tonlaar N, Kunnavakkam R, et al. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer recurrence in men treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyad MA, Merrick GS, Butler WM, et al. Statins, especially atorvastatin, may improve survival following brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urol Nurs. 2006;26:298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soto DE, Daignault S, Sandler HM, et al. No effect of statins on biochemical outcomes after radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2009;73:158. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton RJ, Banez LL, Aronson WJ, et al. Statin medication use and the risk of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) Database. Cancer. 116:3389. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollmeier MA, Katz MS, Mak K, et al. Improved biochemical outcomes with statin use in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 May 6; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.006. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krane LS, Kaul SA, Stricker HJ, et al. Men presenting for radical prostatectomy on preoperative statin therapy have reduced serum prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2010;183:118. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, et al. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:930. doi: 10.1038/nrc1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton RJ, Freedland SJ. Rationale for statins in the chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9:189. doi: 10.1007/s11934-008-0034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makarov DV, Trock BJ, Humphreys EB, et al. Updated nomogram to predict pathologic stage of prostate cancer given prostate-specific antigen level, clinical stage, and biopsy Gleason score (Partin tables) based on cases from 2000 to 2005. Urology. 2007;69:1095. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]