Abstract

Background and purpose

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are used by some arthroplasty registries to evaluate results after surgery, but non-response may bias the results. The aim was to identify a potential bias in the outcome scores of subgroups in a cohort of patients from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR) and to characterize non-responders.

Methods

Patient-reported outcome of 787 patients operated in 2008 was assessed 12 months postoperatively using the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index. In January 2012, non-responders and incomplete responders were sent a postal reminder. Non-responders to the postal reminder were contacted by telephone. Total WOOS score and WOOS subscales were compared for initial responders (n = 509), responders to the postal reminder (n = 156), and responders after telephone contact (n = 27). The predefined variables age, sex, diagnosis, geographical region, and reoperation rate were compared for responding and non-responding cohorts.

Results

A postal reminder increased the response rate from 65% (6% incomplete) to 80% (3% incomplete) and telephone contact resulted in a further increase to 82% (2% incomplete). We did not find any statistically significant differences in total WOOS score or in any of the WOOS subscales between responders to the original questionnaire, responders to the postal reminder, and responders after telephone contact. However, a trend of worse outcome for non-responders was found. The response rate was lower in younger patients.

Interpretation

Non-responders did not appear to bias the overall results after shoulder replacement despite a trend of worse outcome for a subgroup of non-responders. As response rates rose markedly by the use of postal reminders, we recommend the use of reminders in arthroplasty registries using PROMs.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) after orthopedic surgery are used by some registries (Malchau et al. 2005, Goodfellow et al. 2010, Karrholm 2010, Knutson and Robertsson 2010, Rolfson et al. 2011, Rasmussen et al. 2012). Uncertainty about outcome for patients who do not respond may lead to biased conclusions about the effects of interventions (Gluud 2006).

2 clinical studies of non-responders to mail surveys after total knee arthroplasty found that they had poorer functional outcome and less satisfaction than responders (Kim et al. 2004, Kwon et al. 2010). The same was found in a cohort of patients with rotator cuff tears (Norquist et al. 2000). Solberg et al. (2011) traced non-responders to enquiries from a clinical spine surgery registry and found that there was similar outcome in responders and non-responders.

The reliability of data in a registry is crucial for the use of data in research and for extrapolation of data to clinical settings. The main aim of this study was to identify a potential bias in outcome scores of subgroups in a cohort of patients from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR). A second aim was to characterize non-responders.

Patients and methods

The DSR was established in 2004. It is a mandatory, national registry that collects information on all primary and revision arthroplasties of the shoulder joint. The surgeon reports data on the operation through an internet-based reporting system (Rasmussen et al. 2012). Patient-reported functional outcome is assessed by mail survey 12 months postoperatively using the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index. The WOOS is a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool based on 19 questions to be answered on a visual analog scale (Lo et al. 2001). It has been cross-culturally adapted and translated into Danish according to the recommendation by Guillemin et al. (1993). The visual analog scale ranges from 0 to 100, with 100 as the worst score. The questions are divided into 4 domains (physical symptoms, sports and work, lifestyle, and emotions). The total score for all domains is summed to obtain a total score (0–100). The higher the score, the worse the outcome.

Study population

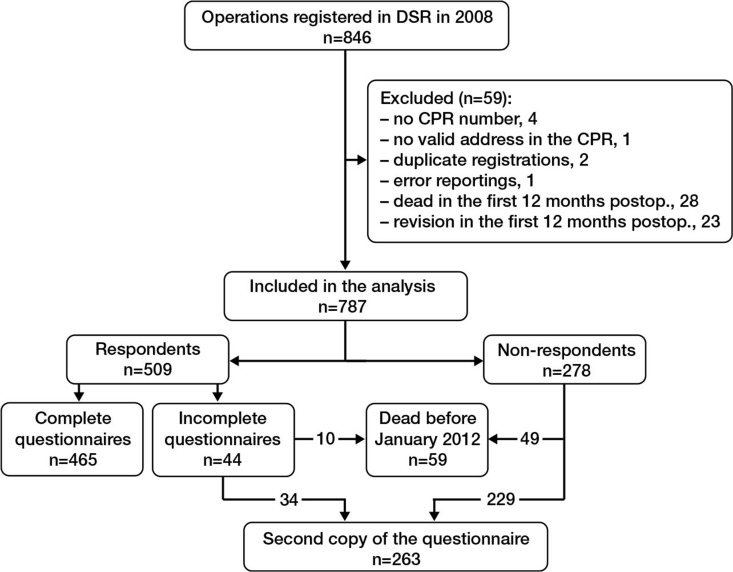

We included 787 patients reported to the DSR from Jan 1, 2008 to Dec 31, 2008 (Figure 1). All had a Danish civil registry number (CPR number) and an address in the Danish national population registry (CPR registry). We excluded 51 operations where the patient had died within 12 months of surgery or had been reoperated in the same shoulder within the first 12 months. The latter exclusion criterion was due to DSR protocol, whereby patients reoperated within 1 year are sent just 1 questionnaire 12 months after the reoperation. Duplicate registrations in same procedure and obvious reporting errors were identified and corrected.

Figure 1.

Study population.

Methods

Age, sex, diagnosis, geographical region, and type of operation for all patients and WOOS score for responders and incomplete responders were available in the DSR. Non-responders and incomplete responders were sent a second copy of the questionnaire in January 2012. The postal addresses were assessed through the CPR registry using the unique civil registry number of each patient. Non-responders of the postal reminder were contacted by telephone after 3 weeks and encouraged to respond to the postal questionnaire.

Analysis and statistics

For analysis, incomplete responders were grouped with responders. Responding and non-responding cohorts were compared with regard to the predefined variables age, sex, diagnosis, geographical region, and reoperation rate. Student’s t-test was used for continuous data and chi-square test was used for nominal data using the continuity correction for 2 × 2 tables. In post hoc explorative analyses with multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied. Responders to the first questionnaire, responders to the postal reminder, and responders after telephone contact were compared with regard to total WOOS score and WOOS subscales using the Mann-Whitney U-test. A clinically relevant difference in outcome was defined as a difference in total WOOS score of ≥ 10 points based on the opinion of the surgeons at our department. Differences in outcome scores or predefined variables was considered statistically significant at p-values of < 0.05. All p-values were 2-sided. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for median differences were calculated with the bootstrapping method using the R bootstrapping package. We used SPSS for Windows version 20.0 for all other statistical analyses.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0015 / HEH.750.41-12).

Results

787 patients who had been sent a postal questionnaire 12 months postoperatively were enrolled in the study. Mean age was 69 (24–96) years and 72% were women (Table 1). 94% were primary operations and 6% were revisions. 82% of the patients had hemiprostheses, 13% had reverse prostheses, 4% had total shoulder prostheses, and for 2% the type of prostheses was not reported.

Table 1.

Functional outcome: WOOS scores. Values are median (interquartile range)

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOOS Total | 40 (17–63) | 47 (21–65) | 49 (22–68) | 41 (18–64) | 7.5 (–1.9 to 15) | 0.3 | 8.6 (–8.7 to 24) | 0.2 |

| WOOS Physical symptoms | 30 (11–50) | 34 (11–57) | 38 (21–57) | 32 (11–54) | 3.5 (–2.2 to 9.8) | 0.3 | 10 (–8.2 to 24) | 0.2 |

| WOOS Sport and work | 42 (19–63) | 54 (23–78) | 72 (29–91) | 53 (23–77) | 4.4 (–4.0 to 15) | 0.3 | 20 (–12 to 29) | 0.08 |

| WOOS Lifestyle | 44 (19–71) | 51 (23–72) | 57 (26–80) | 46 (20–72) | 6.4 (–5.3 to 15) | 0.4 | 3.9 (–3.5 to 26) | 0.5 |

| WOOS Emotions | 28 (5–66) | 37 (7–68) | 47 (6–69) | 32 (5–67) | 9.7 (–5.0 to 22) | 0.2 | 18 (–19 to 35) | 0.5 |

A I. Responders to the first questionnaire a n = 509

B II. Responders to the reminder questionnaire a n = 156

C III. Responders after telephone follow-up n = 27

DAll Responders (original + reminder questionnaire + telephone) n = 656

E Difference in medians (I vs. II) (95% CI)

F P-value of difference (I vs. II)

G Difference in medians (I + II vs. IIl) (95% CI)

H P-value of difference (I + II vs. IIl)

a Incomplete responses to the original questionnaire are part of group I, and if the patients responded to the postal reminder, their second answer is part of group II.

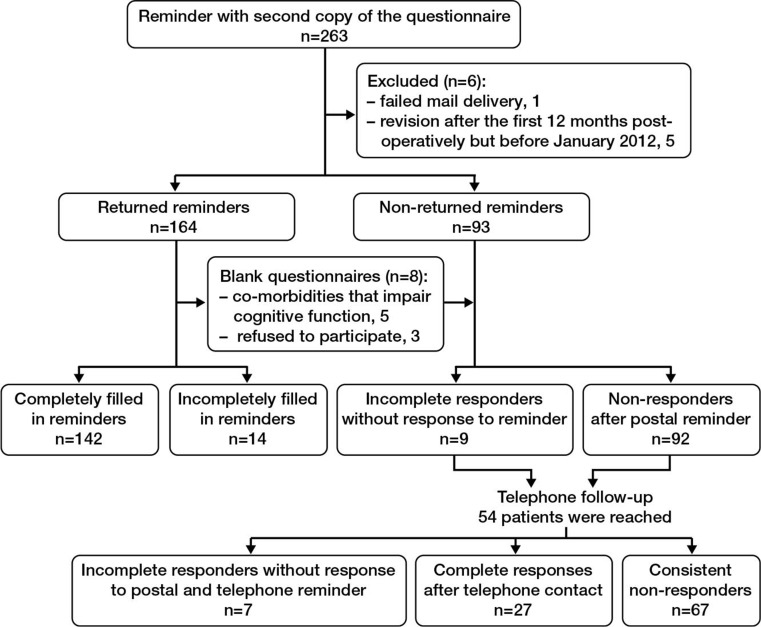

Response rates

465 patients (65%) responded to the original questionnaire 12 months postoperatively (6% had filled it in incompletely). 156 patients responded to the postal reminder, increasing the response rate for all patients included to 80% (with 3% incomplete) (Figure 2). Telephone follow-up resulted in 27 responses out of 54 patients reached, further increasing the overall response rate to 82% (with 2% incomplete).

Figure 2.

Responses after the reminder.

Outcome scores

No differences in total WOOS scores and WOOS subscales between responders to the original questionnaire, responders to the postal reminder, and responders after telephone contact reached statistical significance (Table 1). The median total WOOS score was 7.5 (CI: –1.9 to 15) percentage points higher for responders to the postal reminder than for responders to the first questionnaire (p = 0.3). For responders after telephone contact, the median total WOOS score was 8.6 (CI: –8.7 to 23) percentage points higher than for responders after the questionnaire or the postal reminder (p = 0.2). The CIs for differences in median total WOOS scores included the value 0 and the minimal clinically relevant difference: 10. Thus, we could not determine whether there was a clinically relevant difference in outcome between responders and non-responders.

Predefined variables

There was no statistical evidence for differences in mean age, sex, or geographical region between responders and non-responders to the original questionnaire (Table 2). Response rate was related to diagnosis (p = 0.002), but post hoc explorative analysis comparing the 4 major indications—arthritis, arthrosis, fracture, and cuff arthropathy, involving 93% of the patients—revealed no differences in response rate between these subgroups (uncorrected p-values: 0.2, 0.6, 0.8, 0.8, 1.0, 0.9; all corrected p-values 1). After the postal reminder, no statistically significant difference was found between responders and non-responders with respect to sex, diagnosis, geographical region, and reoperation status. Non-responders to the postal reminder were younger, with a mean age of 65 (24–89) years as opposed to a mean age of 69 (26–94) years for responders (p = 0.002). Consistent non-responders showed no statistically significant differences in sex, diagnosis, geographical region, or reoperation status compared to the pooled group of all responders. However, they were generally younger than responders, with a mean age of 64 (24–87) years as compared to 69 (26–94) years for responders (p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of predefined variables

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (95% CI) | 69 (68–70) | 70 (69–71) | 68 (67–70) | 65 (62–68) | 64 (61–68) | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Sex (%) | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |||||

| F | 565 (72) | 374 (74) | 191 (69) | 64 (69) | 44 (66) | |||

| M | 222 (28) | 135 (27) | 87 (31) | 29 (31) | 23 (34) | |||

| Diagnosis (%) | 0.002 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |||||

| Arthritis | 31 (4) | 20 (4) | 11 (4) | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | |||

| Osteoarthrosis | 231 (29) | 148 (29) | 83 (30) | 24 (26) | 17 (25) | |||

| Fracture | 406 (52) | 275 (54) | 131 (47) | 49 (53) | 39 (58) | |||

| Arthropathy of the rotator cuff | 64 (8) | 41 (8) | 23 (8) | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | |||

| Necrosis of the humeral head | 21 (3) | 15 (3) | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | |||

| Other diagnosis | 25 (3) | 7 (1) | 18 (7) | 6 (7) | 4 (6) | |||

| Unknown | 9 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |||

| Geographical region (%) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||

| The capital area (Copenhagen) | 223 (28) | 140 (28) | 83 (16) | 29 (31) | 23 (34) | |||

| North of Jutland | 82 (10) | 56 (11) | 26 (9) | 6 (7) | 5 (8) | |||

| The middle part of Jutland | 265 (34) | 165 (32) | 100 (36) | 37 (40) | 27 (40) | |||

| South of Jutland and Fyn | 143 (18) | 102 (20) | 41 (15) | 11 (12) | 6 (9) | |||

| Sealand | 74 (9) | 46 (9) | 28 (10) | 10 (11) | 6 (9) | |||

| Reoperated (%) | 0.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 50 (6) | 11 (2) | 39 (14) | 6 (7) | 4 (6) | |||

| No | 737 (94) | 498 (98) | 239 (86) | 87 (94) | 63 (94) |

A All (n = 787)

B I. Responders (n = 509)

C II. Non-responders (n = 278)

D III. Non-responders after reminder (n = 92), a subgroup of non-responders (II)

E IV. Consistent non-responders (n = 67), a subgroup of III.

F P-value of difference (I vs. II)

G P-value of difference, group III compared to responders of the original and reminder questionnaire (initial responders + responders to the reminder).

H P-value of difference, group IV compared to all responders (initially + after reminder + after telephone contact).

Revision and outcome

A post hoc analysis revealed a median total WOOS score of 57 (IQR: 32–68) for revision patients and 41 (IQR: 17–63) for primarily operated patients. This difference of 16 (CI: 0–23) percentage points was clinically and statistically significant (p = 0.03). When revision patients were left out of the analyses, the median total WOOS scores were only 2 (CI: –8¬ to 12) percentage points higher for responders to the postal reminder than for responders to the original questionnaire (p = 0.2). On the other hand, the median total WOOS scores for responders after telephone contact were 10 (CI: 5–25) percentage points higher than the median total WOOS scores for initial responders and responders to the postal reminder (p = 0.1).

Discussion

We did not find any statistical evidence for different outcome scores for respondents and non-respondents at one-year follow-up in patients after shoulder replacement. However, a trend of worse outcome scores for non-responders was noted. This trend is partly explained by the fact that there was a higher proportion of revision patients in the group of non-responders; revision was associated with inferior outcome scores. When revision patients were excluded, the trend of worse outcome in responders to the postal reminder disappeared. However, for the subgroup of non-responders that responded after telephone contact, the trend of worse outcome scores persisted. This trend might have become statistically significant if the group of responders after telephone contact had been larger. We were not able to reject or confirm that the trend of worse outcome scores was clinically relevant according to our predefined minimal clinically relevant difference. Younger patients were less likely to respond.

Our results do not agree with the findings in clinical studies, in which primary non-responders to PROMs have reported worse outcome (Norquist et al. 2000, Kim et al. 2004, Kwon et al. 2010). Rather, our findings are in line with those of Solberg et al. (2011), who found similar patient-reported outcome for responders and non-responders in the Norwegian spine surgery registry. They assessed sequential patient-reported outcomes 3 times over a 2-year follow-up period, and defined non-responders as those failing to respond after 1 reminder had been sent. In a younger population with a mean age of 42 years, they found a higher proportion of non-responders than we did. They found that non-responders were younger and had fewer complications.

One reason for the discrepancy in findings between clinical studies and large registry studies could be that the study design, the setting, and patient selection differ. In clinical studies, rigorous efforts can be made to trace the non-responders, and eligibility criteria can restrict the population studied to avoid the influence of factors that might affect patient-reported outcome and response behavior.

One strength of the present study was the availability of the unique civil registry number, which allows linkage of the individuals registered in the registry database to the national population registry. As the national population registry is continuously updated regarding postal address and date of death, it enabled us to reach almost all the living non-responders by postal questionnaire. It has been documented that the use of both telephone and postal questionnaires can introduce information bias (Norquist et al. 2000, Grimes and Schulz 2002, Ludemann et al. 2003). Thus, we did not interview the patients by telephone but only encouraged them to respond by mail.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, we were unable to reach all non-responders to the postal reminder by telephone, because there is no complete database with telephone numbers. Secondly, the time delay between the first questionnaire 12 months postoperatively and the postal reminder in January 2012 limited the completeness of follow-up, as more patients were lost to follow-up due to death or reoperation. Thirdly, we cannot exclude improvement or deterioration in WOOS scores in the period between the first questionnaire and the reminder. A smaller, gradual deterioration in joint evaluation scores has been reported after hip and knee replacement (Ritter et al. 2004). Due to differences in weight load on joints of the upper and lower extremities, these results may not be directly extrapolated to our cohort, and outcome of shoulder replacement is considered to be almost stable after one year (Wirth et al. 2006, Ohl et al. 2010, Cazeneuve and Cristofari 2011). Thus, we presume that deterioration or improvement in WOOS scores as a result of the time delay was of minor importance in our study. Hence, if a clinically relevant difference in patient-reported functional outcome existed between responders and non-responders 12 months postoperatively, we would expect the difference to persist after 3 years.

As patients who consistently failed to respond were generally younger, it is likely that communication by e-mail or social media might have reached this subgroup of patients. Moreover, our data suggest that non-responders are a heterogeneous group, and revision proved to be an important factor related to both response behavior and outcome. Several other demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and health-related factors (such as co-morbidity) might influence response behavior and patient-reported outcome. These factors should be investigated in future studies of patients who do not respond to PROMs.

In conclusion, non-responders did not appear to bias the overall results after shoulder replacement despite there being a trend of worse outcome for a subgroup of non-responders. Age and revision rate were important factors related to non-response, and these should be considered when PROMs in registries are being interpreted. We recommend the use of reminders in arthroplasty registries using PROMs, as reminders raised the response rates markedly.

Acknowledgments

AP: preparation of the protocol, data processing, statistics, and writing on the paper. JR: conception and design of the study, and interpretation of data. SB: methodological considerations and interpretation of data. BO: interpretation of data. All the authors reviewed the protocol and the manuscript.

We thank Tobias Wirenfeldt Klausen for statistical advice and Danish orthopaedic surgeons for data reporting.

Approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency was obtained on December 30, 2011 with the ID-number: 2007-58-0015 / HEH.750.41-12.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Long term functional outcome following reverse shoulder arthroplasty in the elderly. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(6):583–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluud LL. Bias in clinical intervention research. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(6):493–501. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow JW, O’Connor JJ, Murray DW. A critique of revision rate as an outcome measure: re-interpretation of knee joint registry data. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(12):1628–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):248–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417–32. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J. The Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (www.shpr.se) Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):3–4. doi: 10.3109/17453671003635918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lonner JH, Nelson CL, Lotke PA. Response bias: effect on outcomes evaluation by mail surveys after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson K, Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (www.knee.se) Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):5–7. doi: 10.3109/17453671003667267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SK, Kang YG, Chang CB, et al. Interpretations of the clinical outcomes of the nonresponders to mail surveys in patients after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):133–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo IK, Griffin S, Kirkley A. The development of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: The Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(8):771–8. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludemann R, Watson DI, Jamieson GG. Influence of follow-up methodology and completeness on apparent clinical outcome of fundoplication. Am J Surg. 2003;186(2):143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H, Garellick G, Eisler T, et al. Presidential guest address: the Swedish Hip Registry: increasing the sensitivity by patient outcome data. Clin Orthop. 2005;(441):19–29. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000193517.19556.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norquist BM, Goldberg BA, Matsen FA. III. Challenges in evaluating patients lost to follow-up in clinical studies of rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000;82(6):838–42. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl X, Nerot C, Saddiki R, Dehoux E. Shoulder hemi arthroplasty radiological and clinical outcomes at more than two years follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(3):208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JV, Jakobsen J, Brorson S, Olsen BS. The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry: clinical outcome and short-term survival of 2,137 primary shoulder replacements. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(2):171–3. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.665327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter MA, Thong AE, Davis KE, et al. Long-term deterioration of joint evaluation scores. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004;86(3):438–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson O, Karrholm J, Dahlberg LE, Garellick G. Patient-reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(7):867–75. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.25737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg TK, Sorlie A, Sjaavik K, et al. Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine? Acta Orthop. 2011;82(1):56–63. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.548024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MA, Tapscott RS, Southworth C, Rockwood CA. Jr. Treatment of glenohumeral arthritis with a hemiarthroplasty: a minimum five-year follow-up outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(5):964–73. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.03030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]