Abstract

Background and purpose

Little is known about the effect of the learning curve for different types of total hip arthroplasties (THAs). We investigated the prostheses survival of THAs just after the implementation of a model new to the hospital, and compared these results with the results of THAs done when more than 100 implantations had been undertaken. In addition, we investigated whether differences exist between different types of femoral stems and acetabular cups at the early implementation phase.

Patients and methods

We used comprehensive registry data from all units (n = 76) that performed THAs for primary osteoarthritis in Finland between 1998 and 2007. Complete data including follow-up data to December 31, 2010 or until death were available for 33,819 patients (39,125 THAs). The stems and cups used were given order numbers in each hospital and classified into 5 groups: operations with order number (a) 1–15, (b) 16–30, (c) 31–50, (d) 51–100, and (e) > 100. We used Cox’s proportional hazards modeling for calculation of the adjusted hazard ratios for the risk of revision during the 3 years following the implementation of a new THA endoprosthesis type in the groups.

Results

Introduction of new endoprosthesis types was common, as more than 1 in 7 patients received a type that had been previously used in 15 or less operations. For the first 15 operations after a stem or cup type was introduced, there was an elevated risk of revision (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5). There were differences in the risk of early revision between stem and cup types at implementation.

Interpretation

The first 15 operations with a new stem or cup model had an increased risk of early revision surgery. Stems and cups differed in their early revision risk, particularly at the implementation phase. Thus, the risk of early revision at the implementation phase should be considered when a new type of THA is brought into use.

Based on comparisons of implant survival, the type of THA model has an effect on the long-term risk of revision surgery (Mäkelä et al. 2008, 2010). However, very little is known about the effect of the introduction of a new THA model on the risk of early revision. Recently, Anand et al. (2011) showed that more than a quarter of the new endoprosthesis types introduced into the Australian market had a higher revision rate than established models, with a minimum duration of follow-up of 5 years.

Higher risk of early revision has already been shown with total knee arthroplasty (TKA) when introducing a new type of endoprosthesis in a hospital (Peltola et al. 2012). This phenomenon is to be expected when, in TKA, optimal implant positioning strongly depends on precise and familiar use of implant-specific instrumentation (such as resection guides and cutting blocks). In THA, however, such factors may play a less important role. We therefore hypothesized that the first THA patients to be operated on with any endoprosthesis would not have a higher revision rate than patients whose implants were well known.

In addition to studying the overall effect of implementation of new models, we analyzed specific differences in femoral stem and acetabular cup types regarding early revision risk during the implementation phase by studying the 10 most common stem and cup pairs.

Patients and methods

We identified all 36,626 patients in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR) who had had primary THA (42,673 operations) due to OA between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2007. Of these, we excluded 2,107 operations (in 1,607 patients) for which information regarding the endoprosthesis type (the name of either the stem or cup component) or the fixation technique was missing. Also, operations with resurfacing arthroplasty were excluded (n = 1,441). After exclusions, the final study data included 33,819 patients who had 39,125 THAs with at least 3 years of follow-up—or who had died before the end of follow-up (Table 1). The data are hip-specific. Altogether, 2,346 revisions were done on these before December 31, 2010, and 1,269 of the revisions were done within 3 years of the primary operation.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for 39,125 total hip arthroplasty operations in Finland from 1998 to 2007

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total no. of operations | 39,125 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16,849 | 43.1 |

| Age | ||

| < 50 years | 1,044 | 2.7 |

| 50–59 years | 5,929 | 15.2 |

| 60–69 years | 12,991 | 33.2 |

| 70–79 years | 15,258 | 39.0 |

| ≥ 80 years | 3,903 | 10.0 |

| Operation | ||

| Bilateral | 1,373 | 3.5 |

| Cemented | 18,072 | 46.2 |

| Cementless | 14,769 | 37.7 |

| Hybrid | 6,284 | 16.1 |

| Bone grafts | 1,468 | 3.8 |

| Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics | 38,535 | 98.5 |

| Operations with the 10 most common | ||

| stem and cup pairs | 22,271 | 56.9 |

| The 10 most common stem and cup pairs | ||

| 1 Exeter Universal / Contemporary | 5,925 | 15.1 |

| 2 Spectron EF / Reflection All-Poly | 2,868 | 7.3 |

| 3 Exeter Universal / Exeter All-Poly | 2,838 | 7.3 |

| 4 Biomet Collarless / Biomet Vision | 2,210 | 5.6 |

| 5 Link Lubinus SP II / Link IP Acetabular Cups | 1,712 | 4.4 |

| 6 ABG II / ABG II | 1,617 | 4.1 |

| 7 ABG HA / ABG II | 1,436 | 3.7 |

| 8 Link Lubinus SP II / Link Lubinus Eccentric | 1,430 | 3.7 |

| 9 Biomet Collarless / Recap (Biomet) | 1,284 | 3.3 |

| 10 Biomet Collarless / M2A 38 Flared Acetabular Cup |

951 | 2.4 |

We linked data in the FAR for the period 1998–2010 with data in hospital discharge registers for the period 1998–2010 using personal identification numbers. The coverage and reliability of the registers is high (Keskimäki and Aro 1991, Puolakka et al. 2001, Gissler and Haukka 2004). The FAR contains information from primary and revision THAs performed in Finland since 1980, from every clinic performing arthroplasty. We also linked the death statistics from Statistics Finland to the data to take account of the censoring of patients. We used both the discharge register and the arthroplasty register to track all the revisions performed. Revisions are reliably recorded in registers, and they are an accepted outcome measure in register-based THA research (Serra-Sutton et al. 2009). For analysis of the effect of endoprosthesis introduction on early revision, the follow-up was restricted to 3 years since revisions soon after the primary operation are often due to technical shortcomings in the primary operation, while later revisions are more likely to be the result of normal wear (Clohisy et al. 2004, Dobzyniak et al. 2006, Mäkelä et al. 2008, 2010). In this study, revisions for any reason—including removal of an endoprosthesis—were considered to be true revisions.

From the FAR, we obtained the number of every endoprosthesis type used between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 1997. This was done separately for each hospital, and for different types of stem and cup components. Using hip-specific data from the FAR from January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2007, for each THA carried out during this period we defined the ordinal number of the stem and cup component in the operating hospital.

A stem is not necessarily used together with a specific cup, and there are numerous stem and cup combinations (pairs), which complicates the analyses. We formed 2 versions of pairwise order numbering based on the lower (minimum) and the higher (maximum) order number of the stem or cup in a pair. Thus, for analysis of an overall learning effect in THA when introducing a new model not used previously in the hospital, we constructed 3 statistical models: 2 models with pairwise order numbering, and 1 model including both the stem and cup order numberings individually.

We classified the operations with respect to the ordinal number into 5 classes: group A (operations with order number 1–15), group B (16–30), group C (31–50), group D (51–100), and group E (over 100). We compared the cases in groups A to D with those in group E. We used Cox’s proportional hazards model to compare the groups so that censoring because of deaths and the timing of the revision would be taken into account. Because we knew the dates of both primary surgery and revision surgery, we used the time in days from primary surgery to revision or censoring as the dependent variable.

We performed the analysis in 2 stages. First, we estimated the different types in the whole study to investigate the overall effect of implementation of new implant types. We performed 4 estimations with an incrementally wider set of confounding variables, and used the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC, respectively) to evaluate the performance of the model. With this approach, we wanted to perform extensive adjustments for potentially confounding factors, at the same time checking that we were not overadjusting. The first model was unadjusted, the second model was adjusted with patient characteristics (sex, and age classified into 5 groups (< 51, 51–60, 61–70, 71–80, and > 80 years)), the third model had operation-related variables added, and the fourth model had hospital-level variables added. We included cementing, bilaterality (both hips in the same operation), bone graft use, and intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis as operation-related variables. The hospital-level variables possibly affecting the outcome of primary surgery were constructed for each calendar year (share of hospital arthroplasty volume taken by THA, hospital’s femoral model use per 100 THAs, and hospital hip arthroplasty volume). Model 2 was stratified for sex, and models 3 and 4 were stratified for sex and fixation technique. Based on the information criteria, model 2 with age and sex only was better than the more complex models 3 and 4. In addition to the age- and sex-adjusted results, we also present the unadjusted hazard ratios for the ordinal number classes.

In the second phase, we identified the 10 most common stem and cup pairs and separated Cox model analyses for the pairs with at least 100 observations in the different ordinal number groups. For each selected pair, the model was estimated for the cases with this pair only with the operations in group E (over 100 operations with the pair in the hospital) as the reference, using the order numbering of the stem and cup separately, or the pairwise order numbering (both minimum and maximum). For the pairs, we present only age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios.

In all models, the proportional hazards assumption was investigated by testing for a non-zero slope in a generalized linear regression of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals on functions of time (Grambsch and Therneau 1994). In our data, a person may have 2 observations. We tested and found that the violation of the assumption of independent observations did not affect the results. In addition, we considered the clustering of patients in hospitals by performing all the analyses with shared gamma frailty models. The results of these models were almost identical to the results of conventional Cox regression models that we present.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Finland on January 28, 2010.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the entire study population are given in separate tables for operation-specific and hospital-specific variables (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). In the data, there are 96 stem types and 85 cup types. These components were used in 467 different combinations, i.e. different stem and cup pairs. A large proportion of the endoprosthesis models had been used in only a small number of operations. Of the stem types, 62 were used in less than 100 operations; of the cup types, 47 were used in less than 100 operations, accounting for about 3% of the operations. During the study period, altogether 87 stem and 79 cup brands were introduced in at least 1 hospital. These introductions contributed to 5,967 operations in the first stage of introduction of a new endoprosthesis model (operations in group A with pairwise minimum order numbering) in all of the 76 hospitals in the period from January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2007. Of all the operations, almost 1 in 6 were done in the first stage of introducing the endoprosthesis (group A, pairwise minimum order numbering). Cups accounted for a larger share of these introductions than stems.

Table 2.

Descriptions of the hospital-level variables in a study of endoprosthesis implementation in Finland for 39,125 THA operations

| Proportion of arthroplasty operations in hospital that were THAs, mean (SD) |

0.58 | (0.10) |

| Proportion of all operations in hospital that were arthroplasty, mean (SD) |

0.13 | (0.21) |

| Femur models per 100 THAs in hospital, mean (SD) |

5.51 | (4.74) |

| Hospital’s annual arthroplasty volume, n (%) | ||

| < 51 operations | 2,135 | (5.5) |

| 51–150 operations | 9,999 | 25.6) |

| 151–300 operations | 8,814 | (22.5) |

| > 300 operations | 18,177 | (46.5) |

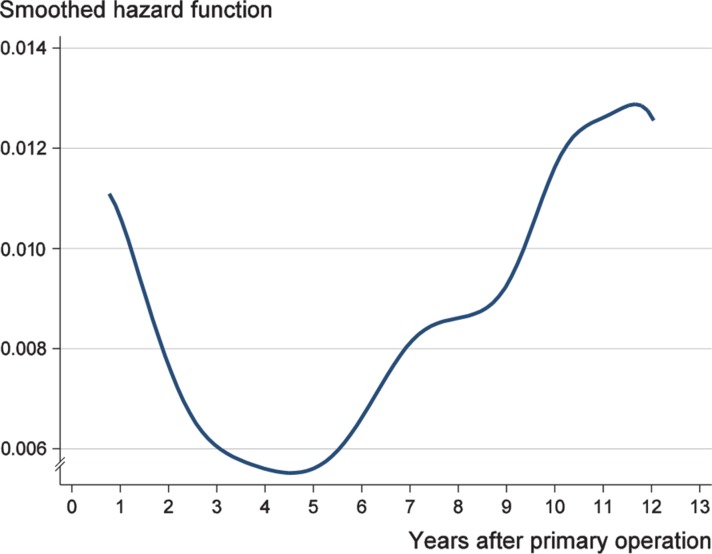

The unadjusted hazard ratios show that the first 15 operations with a new endoprosthesis model had a higher risk of early revision for the order numbering of both stem and cup brands, and also for the combined order numbering. The risk of early revision was statistically significant also in the age- and sex-adjusted model (HR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5) (Table 3). Thus, in THA performed due to osteoarthritis, there appears to have been a learning curve due to the introduction of a new stem or cup type. The smoothed hazard function showed that the risk of revision rapidly declined during the first 3 years after the primary operation (Figure). Most of the early revisions were performed during the year after the primary operation.

Table 3.

Estimated hazard ratios for revision over 3 years after primary THA in a population-based study of 39,125 operations

| Ordinal number group Operation |

No. of operations |

No. of revisions |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

Age- and sex-adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum of stem and cup order numbers | ||||

| 1–15 | 5,967 | 228 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| 16–30 | 3,980 | 123 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| 31–50 | 4,185 | 135 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| 51–100 | 6,820 | 220 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| 101– | 18,173 | 527 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Maximum of stem and cup order numbers | ||||

| 1–15 | 2,428 | 89 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| 16–30 | 1,868 | 59 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) |

1.0 (0.8–1.4) |

| 31–50 | 2,264 | 86 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) |

1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| 51–100 | 4,226 | 153 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 101– | 28,339 | 846 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Stem and cup order number separately in the same model | ||||

| Stem | ||||

| 1–15 | 3,653 | 141 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| 16–30 | 2,536 | 76 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) |

0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| 31–50 | 2,740 | 93 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

1.0 (0.8–1.3) |

| 51–100 | 4,707 | 162 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| 101– | 25,489 | 761 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Cup | ||||

| 1–15 | 4,742 | 176 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 16–30 | 3,312 | 106 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| 31–50 | 3,709 | 128 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| 51–100 | 6,339 | 211 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| 101– | 21,023 | 612 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

We also performed separate analyses of the 10 most common stem and cup pairs in order to analyze the pair-specific learning effect (Table 4). Specifically, we analyzed the stem- and cup-specific differences in early revision risk for the order number groups when compared to the operations with the same implant pair having an order number greater than 100.

Table 4.

Number of operations in stages of introduction for the 10 most common stem and cup pairs

| Numbering based on Operation order number |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Pair 6 |

7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of operations | 5,925 | 2,868 | 2,838 | 2,210 | 1,712 | 1,617 | 1,436 | 1,430 | 1,284 | 951 |

| No. of early revisions | 153 | 60 | 90 | 81 | 59 | 60 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 26 |

| No. of hospitals | 53 | 34 | 31 | 45 | 18 | 33 | 34 | 25 | 35 | 24 |

| Combined (minimum) | ||||||||||

| 1–15 | 404 a | 347 a | 125 | 367 a | 38 | 299 a | 172 a | 50 | 200 a | 249 a |

| 16–30 | 387 a | 277 a | 48 | 266 a | 27 | 228 a | 165 a | 34 | 181 a | 167 a |

| 31–50 | 478 a | 286 a | 101 | 335 a | 35 | 220 a | 224 a | 92 | 198 a | 160 a |

| 51–100 | 865 a | 471 a | 324 | 443 a | 89 | 410 a | 428 a | 262 | 271 a | 258 a |

| 101– | 3,791 a | 1,487 a | 2,240 | 799 a | 1,523 | 460 a | 447 a | 992 | 434 a | 117 a |

| Combined (maximum) | ||||||||||

| 1–15 | 227 a | 320 a | 86 | 54 | 33 | 82 | 117 a | 29 | 17 | 144 |

| 16–30 | 227 a | 255 a | 57 | 38 | 29 | 50 | 122 a | 16 | 38 | 59 |

| 31–50 | 314 a | 266 a | 85 | 85 | 35 | 61 | 126 a | 28 | 51 | 68 |

| 51–100 | 624 a | 463 a | 250 | 145 | 87 | 198 | 360 a | 13 | 77 | 102 |

| 101– | 4,533 a | 1,564 a | 2,360 | 1,888 | 1,528 | 1,226 | 711 a | 1,344 | 1,101 | 316 |

| Stem | ||||||||||

| 1–15 | 233 a | 323 a | 87 | 65 | 34 | 298 a | 151 a | 29 | 17 | 25 |

| 16–30 | 231 a | 259 a | 56 | 46 | 29 | 228 a | 117 a | 16 | 38 | 23 |

| 31–50 | 311 a | 276 a | 85 | 99 | 35 | 214 a | 135 a | 28 | 51 | 26 |

| 51–100 | 634 a | 472 a | 251 | 159 | 89 | 412 a | 353 a | 37 | 81 | 59 |

| 101– | 4,516 a | 1,538 a | 2,359 | 1,841 | 1,525 | 465 a | 680 a | 1,320 | 1,097 | 818 |

| Cup | ||||||||||

| 1–15 | 398 a | 344 a | 124 | 356 a | 37 | 83 | 138 a | 50 | 200 a | 249 a |

| 16–30 | 383 a | 273 a | 49 | 258 a | 27 | 50 | 170 a | 34 | 181 a | 167 a |

| 31–50 | 481 a | 276 a | 101 | 321 a | 35 | 67 | 215 a | 92 | 198 a | 160 a |

| 51–100 | 855 a | 462 a | 323 | 429 a | 87 | 196 | 435 a | 238 | 267 a | 258 a |

| 101– | 3,808 a | 1,513 a | 2,241 | 846 a | 1,526 | 1,221 | 478 a | 1,016 | 438 a | 117 a |

a The order-numbering groups that were subject to hazard ratio analysis.

The model-specific analyses (Table 5) showed that 3 out of 10 pairs had an increased risk of early revision at the introduction phase. Early revision risk after the implementation of a new endoprosthesis type increased with the Contemporary cup (operations 1 to 15: HR = 2.6, CI: 1.6–4.2) in the Exeter Universal/Contemporary pair, the Spectron EF stem (HR = 2.1, CI: 1.0–4.1) in the Spectron EF/Reflection All-Poly pair, and with the ABG HA stem (HR = 2.7, CI: 1.1–6.5) in the ABG HA/ABG II pair.

Table 5.

Pair-specific age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios for stages of implant introduction a

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–15 | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 2.6 (1.6–4.2) |

| 16–30 | 2.2 (1.3–3.7) | 1.7 (0.9–3.3) | 1.7 (0.8–3.3) | 2.3 (1.4–3.8) | |

| 31–50 | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 2.1 (1.2–3.5) | 2.2 (1.3–3.7) | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | |

| 51–100 | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | |

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 2 | 1–15 | 1.9 (0.9–3.7) | 2.1 (1.1–4.2) | 2.1 (1.0–4.1) | 1.9 (1.0–3.8) |

| 16–30 | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 1.1 (0.4–2.8) | |

| 31–50 | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 1.1 (0.4–2.8) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 1.2 (0.5–3.0) | |

| 51–100 | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 1.7 (0.9–3.3) | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | |

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 4 | 1–15 | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | ||

| 16–30 | 0.6 (0.3–1.4) | 0.6 (0.3–1.5) | |||

| 31–50 | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | |||

| 51–100 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | |||

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 6 | 1–15 | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | ||

| 16–30 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | |||

| 31–50 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | |||

| 51–100 | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | |||

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 7 | 1–15 | 2.0 (0.8–5.4) | 2.5 (1.0–6.7) | 2.7 (1.1–6.5) | 1.9 (0.7–5.2) |

| 16–30 | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 1.2 (0.3–4.1) | 1.2 (0.3–4.3) | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | |

| 31–50 | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 1.1 (0.3–4.0) | 0.7 (0.2–3.2) | 1.6 (0.6–4.2) | |

| 51–100 | 1.1 (0.4–2.7) | 1.9 (0.9–4.1) | 2.0 (0.9–4.4) | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | |

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 9 | 1–15 | 1.7 (0.7–4.0) | 1.7 (0.7–4.0 | ||

| 16–30 | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) | |||

| 31–50 | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) | |||

| 51–100 | 0.7 (0.2–1.9) | 0.7 (0.2–1.9) | |||

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 10 | 1–15 | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | ||

| 16–30 | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | |||

| 31–50 | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | |||

| 51–100 | 0.9 (0.3–2.1) | 0.9 (0.3–2.1) | |||

| 100– | 1.0 | 1.0 |

a Due to small number of observations in all numbering groups, the pairs 3, 5, and 8 have been excluded from the pairwise analysis.

A Pair

B Order no. of the operation

C Order numbering, minimum, HR (95% CI)

D Order numbering, maximum, HR (95% CI)

E Order numbering, stem, HR (95% CI)

F Order numbering, cup, HR (95% CI)

Discussion

We found a learning curve in THA when a new stem or cup type was introduced. For the first 15 operations, the risk was elevated (HR = 1.3, CI: 1.1–1.5). However, there were differences in the type-specific early revision risk between the stages of introduction, reflecting that some types are easier to implement than others. We also found that the introduction of new endoprosthesis types is common in Finland, with 1 in every 7 patients receiving an endoprosthesis type during its implementation phase at that hospital (with 15 or less previous operations).

The possibility of identifying the stage of introduction of an endoprosthesis type for each individual patient in a nationwide population provides unique data. Patients’ personal identification numbers enable linking of hospital discharge register data with implant register data individually for operation details and outcomes. The present study covers an entire population of patients with OA who underwent THA over a 13-year period, and the findings reflect ordinary healthcare practice. Furthermore, the analysis was performed on a large number of operations with a great variety of endoprosthesis types. The register-based approach allows accurate follow-up of the patients with a minimum number of dropouts. We believe that the external validity of our findings is high.

The smoothed hazard function for revision after primary THA during the follow-up in a population-based study of 39,125 THAs.

Some limitations of the study should be considered. Since there was usually more than 1 endoprosthesis type in use in each hospital, we could not quantify the true amount of technical change linked to the introduction of a particular endoprosthesis. That is, a new implant could be substantially similar to a previously used model and might not reflect an essential change in technology or surgical technique. From our data, we may therefore have underestimated the risk of early revision regarding major changes in surgical technique.

The most common causes of THA revision surgery are aseptic loosening, instability, wear, and infection (Clohisy et al. 2004, Mäkelä et al. 2008, 2010, Jafari et al. 2010). The degree of pain relief and disability varies after THA, and our data may have underestimated the harmful effects of introducing an endoprosthesis model, i.e. there may have been patients with residual pain and disability after failed THA, but not enough to warrant a revision. In our material, we do not have reliable information on the reasons for the revision. In addition, some patient characteristics such as body mass index and physical activity were not available in the register.

Hospital arthroplasty volume, surgical expertise, and a surgeon’s annual case load may reduce the revision risk, although the current evidence is inconclusive (Losina et al. 2004, Judge et al. 2006, Shervin et al. 2007, Manley et al. 2008). We formed statistical models where we controlled for hospital arthroplasty volumes in the analysis of the overall effect of implementation on risk of early revision. The Cox proportional hazards regression for the whole study population showed that, after adjusting for all the patient-, operation-, and hospital-specific variables, the estimated hazard ratios for the stages of introduction were not statistically significantly different. However, statistical testing suggested that this model performed worse than the simpler age- and sex-adjusted model, and due to the risk of over-adjusting we discarded this model.

The register data do not indicate who operated on each patient. Surgeons differ in their skill and case load, and this could have an effect on revision risk. For instance, in the case of an experienced surgeon moving to another hospital, he or she might start in the new hospital with prostheses that are familiar and yet new to the hospital. This could lead to an apparent decrease in the revision risk for introductions.

The learning curve of an orthopedic surgeon has been discussed in the literature, and some studies have been done on the effect of the learning curve on a certain operative technique or implementation of new technology, such as minimally invasive surgery or hip resurfacing (Archibeck and White 2004, Laffosse et al. 2006, Cobb et al. 2007, Seyler et al. 2008, Jablonski et al. 2009, Seng et al. 2009, Nunley et al. 2010, Berend et al. 2011). Most studies have been based on a consecutive series of patients in a single hospital, usually with a single surgeon, and the learning effect is often evaluated with measures related to the operation only (e.g. operating room time, blood loss). We are not aware of any studies that have analyzed at a population level the overall effect of hip endoprosthesis introduction on the early revision rate. Also, we are not aware of any studies that have tried to quantify the effect of endoprosthesis introduction in a hospital specifically for a named endoprosthesis model.

We found an increased risk of early revision at the introduction of some endoprosthesis models (Table 5). All these models have proven to have reasonable long-term results (Mäkelä et al. 2008, 2010). In our register data, the reason for revision cannot be reliably identified and, thus, an explanation for increased risk of early revision in the introduction of a distinct type cannot be given. However, the variation in revision risk associated with the introduction of a new endoprosthesis type in hospital emphasizes the importance of type selection, careful practice with new instruments before the first operation, and the importance of implant and instrument design.

Both internal and external factors have an effect on the choice of endoprostheses in a hospital. Internal, hospital-specific, or surgeon-specific factors include the degree of frustration with the THA model in use (from poor results, complications, or technical troubles), the desire of a newly recruited surgeon to start using an endoprosthesis model that is familiar from his/her old workplace but perhaps new in the current hospital, and the expectation that better results could be obtained with another model following the accumulation of scientific evidence (long-term results). External factors include new technical innovations and the expectation of better results from endoprosthesis types following a new innovation, active marketing, the cost of components, and the regulation of public procurement. Also, suggestions from authorities and colleagues at meetings and at educational events may have an impact on the choice of endoprostheses at a particular hospital. The learning effect of endoprosthesis implementation should always be taken into account when a new endoprosthesis model is introduced into a hospital. In particular, hospital management should have the learning effect of an endoprosthesis in mind when considering any changes in implant selection that are based on competitive tendering or purely on costs.

Our results show that the first 15 operations with a new stem or cup model have an increased risk of early revision surgery. In addition, our analysis indicates that there are differences in the risk of early revision between stem and cup models not previously used in a hospital. At this time, there are numerous endoprosthesis models and brands available on the market and new models are likely to emerge because of the demand for and marketing of new technology. Although introduction of potentially better endoprosthesis models is important, there is a need for managed uptake of new technology. Our results further support the IDEAL recommendations for evaluation of new surgical interventions (McCulloch et al. 2009). Surgeons should be aware of the risks and should preferably practice with the new type beforehand. Surgical units performing arthroplasties might consider the challenge of introducing new endoprosthesis models. Finally, the manufacturers of endoprostheses ought to take the learning effect into account when designing new devices.

Acknowledgments

MP had the original idea for the study, processed the data, performed the statistical analyses, and prepared the first version of the manuscript. All authors took part in the planning of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and in writing of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Anand R, Graves SE, de Steiger RN, et al. What is the benefit of introducing new hip and knee prostheses? J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(Suppl 3):51–4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibeck MJ, White RE., Jr Learning curve for the two-incision total hip replacement. Clin Orthop. 2004;(429):232–8. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150272.75831.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Jr, Adams JB, Sneller MA. Unsatisfactory surgical learning curve with hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2011;93:89–92. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clohisy JC, Calvert G, Tull F, et al. Reasons for revision hip surgery: A retrospective review. Clin Orthop. 2004. pp. 188–92. (429) (429) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cobb JP, Kannan V, Brust K, Thevendran G. Navigation reduces the learning curve in resurfacing total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2007;(463):90–7. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c0a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzyniak M, Fehring TK, Odum S. Early failure in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2006;(447):76–8. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203484.90711.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissler M, Haukka J. Finnish health and social welfare registers in epidemiological research. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2004;14(1):113–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski M, Gorzelak M, Turzanska K, et al. Modified swanson’s hip replacement--intraoperative complications and learning curve of the procedure. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2009;74(1):5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari SM, Coyle C, Mortazavi SM, et al. Revision hip arthroplasty: Infection is the most common cause of failure. Clin Orthop. 2010. 468. pp. 2046–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Judge A, Chard J, Learmonth I, Dieppe P. The effects of surgical volumes and training centre status on outcomes following total joint replacement: Analysis of the hospital episode statistics for england. J Public Health. 2006;28(2):116–24. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskimäki I, Aro S. Accuracy of data on diagnoses, procedures and accidents in the finnish hospital discharge register. Int J Health Sci. 1991;2:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Laffosse JM, Chiron P, Accadbled F, et al. Learning curve for a modified watson-jones minimally invasive approach in primary total hip replacement: Analysis of complications and early results versus the standard-incision posterior approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006;72(6):693–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losina E, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, et al. Early failures of total hip replacement: Effect of surgeon volume. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1338–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley M, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Effect of volume on total hip arthroplasty revision rates in the united states medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90(11):2446–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, et al. No surgical innovation without evaluation: The IDEAL recommendations. The Lancet. 2009;374(9695):1105–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä KT, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, et al. Total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in patients fifty-five years of age or older. An analysis of the Finnish arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90(10):2160–70. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä KT, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, et al. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in patients aged 55 years and older. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):42–52. doi: 10.3109/17453671003635900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunley RM, Zhu J, Brooks PJ, Engh CA, Jr, Raterman SJ, Rogerson JS, Barrack RL. The learning curve for adopting hip resurfacing among hip specialists. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(2):382–91. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1106-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola M, Malmivaara A, Paavola M. Introducing a knee endoprosthesis model increases risk of early revision surgery. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(6):1711–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puolakka T JS, Pajamäki KJJ, Halonen PJ, Pulkkinen PO, Paavolainen P, Nevalainen JK. The finnish arthroplasty register: Report of the hip register. Acta Orthopaedica. 2001;72(5):433–41. doi: 10.1080/000164701753532745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng BE, Berend KR, Ajluni AF. V. LA,Jr. Anterior-supine minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: Defining the learning curve. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Sutton V, Allepuz A, Espallargues M, et al. Arthroplasty registers: A review of international experiences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(01):63. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309090096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyler TM, Lai LP, Sprinkle DI, et al. Does computer-assisted surgery improve accuracy and decrease the learning curve in hip resurfacing? A radiographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2008;90:71–80. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shervin N, Rubash H, Katz J. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: A systematic literature review. Clin Orth. 2007;(45):35–41. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180375514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]