Abstract

Background and purpose

Our unit started to use routine multimodal techniques to enhance recovery for hip and knee arthroplasty in 2008. We have previously reported earlier discharge, a trend toward a reduction in complications, and a statistically significant reduction in mortality up to 90 days after surgery. In this study, we evaluated the same cohort to determine whether survival benefits were maintained at 2 years.

Patients and methods

We prospectively evaluated 4,500 unselected consecutive total hip and knee replacements. The first 3,000 underwent a traditional protocol (TRAD) and the later 1,500 underwent an enhanced recovery protocol (ER). Mortality data were collected from the Office of National Statistics (UK).

Results

There was a difference in death rate at 2 years (TRAD vs. ER: 3.8% vs. 2.7%; p = 0.05). Survival probability up to 3.7 years post surgery was significantly better in patients who underwent an ER protocol.

Interpretation

This large prospective case series of unselected consecutive patients showed a reduction in mortality rate at 2 years following elective lower-limb hip and knee arthroplasty following the introduction of a multimodal enhanced recovery protocol. This survival benefit supports the routine use of an enhanced recovery program for hip and knee arthroplasty.

Randomized controlled trials (Reilly et al. 2005, Andersen et al. 2007, Larsen et al. 2008) and clinical series (McDonald et al. 2011) have shown a significant reduction in length of stay in hospital following lower limb arthroplasty with the implementation of enhanced recovery (ER) programs. ER programs are based on the use of multimodal strategies to improve analgesia while at the same time reducing the surgical stress response and organ dysfunction (including nausea, vomiting, and ileus), thus facilitating earlier patient mobilization and return to oral fluids and diet (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008). This enables commencement of functional rehabilitation within the first few hours after surgery (Husted et al. 2011, McDonald et al. 2011). The use of multimodal strategies has resulted in faster patient rehabilitation and improved satisfaction (Kehlet and Wilmore 2002).

Our hospital introduced an ER program for hip and knee arthroplasty in May 2008. We have previously published our findings of statistically significant reductions in length of hospital stay and mortality within 30 days and 90 days of surgery by the use of an ER program compared to our traditional protocol (Malviya et al. 2011). The 90-day mortality of 0.2% in our unit after implementation of an ER program is similar to that previously reported in units with established ER programs (Husted et al. 2010).

Very few results have been published regarding comparison of longer-term mortality after implementation of ER programs in comparison to controls from a cohort of patients whereby multimodal strategies were not used in the perioperative period. A recent study from the United Kingdom found no difference in mortality 1 year after primary total knee arthroplasty following implementation of an ER program in comparison with a historical cohort (McDonald et al. 2011).

We now report on mortality more than 3 years postoperatively following the introduction of an ER program, in comparison to the results of our traditional protocol.

Patients and methods

Data from 4,500 unselected consecutive primary hip and knee replacements were analyzed. 3,000 procedures were performed between March 2, 2004 and May 1, 2008, immediately prior to implementation of the enhanced recovery program (the traditional (TRAD) group); 1,500 procedures were performed with an enhanced recovery program (the enhanced recovery (ER) group) between May 2, 2008 and November 3, 2009. The treating surgeons’ indications for hip and knee arthroplasty remained unchanged. The protocols that were followed in both groups have been published previously (Malviya et al. 2011).

The patients were from a consecutive unselected series. Comparison of patient demographics before surgery in the 2 groups—as previously published (Malviya et al. 2011)—are presented in Table 1. Chi-squared test was used to compare proportions (Fleiss et al. 2003).

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics preoperatively in the 2 groups

| TRAD (n = 3,000) |

ER (n = 1,500) |

p-value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 69 | 68 | |

| THR | 1368 | 630 | |

| TKR | 1632 | 870 | |

| Sex (M : F) | 1482 : 1518 | 711 : 789 | 0.2 |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 921 (31) | 673 (45) | < 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 143 (5) | 84 (6) | 0.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 211 (7) | 113 (8) | 0.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| insulin-dependent | 20 (0.7) | 18 (1) | 0.09 |

| non-insulin-dependent | 205 (7) | 150 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive | |||

| pulmonary disease | 85 (3) | 67 (4) | 0.006 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 6 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) | 0.6 |

aChi-squared test with continuity correction.

Mortality data were obtained from the Office of National Statistics (ONS). In England, deaths must be registered within 5 days. Burials and cremations cannot be conducted without this registration documentation. These deaths are recorded by the ONS and are added to the patient’s health service record. The cause of death for patients that died within our NHS trust was obtained from inspection of hospital case notes, and was cross-referenced with ONS data.

Statistics

The death rates and cause-of-death data presented for postoperative times up to 2 years include the actual data for all 4,500 patients. There was a greater proportion of patients in the TRAD group with longer follow-up data. The death rates beyond 2 years are therefore only reported using Kaplan-Meier (K-M) survival analysis. K-M survival curves with Greenwood’s 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess and compare the survival probability between groups (TRAD and ER). The log-rank test was used to test for any statistically significant difference between the 2 K-M curves (Bland and Altman 2004). Furthermore, the log-rank test was used to determine whether there were any differences in survival, between hip and knee arthroplasty, within each group.

Results

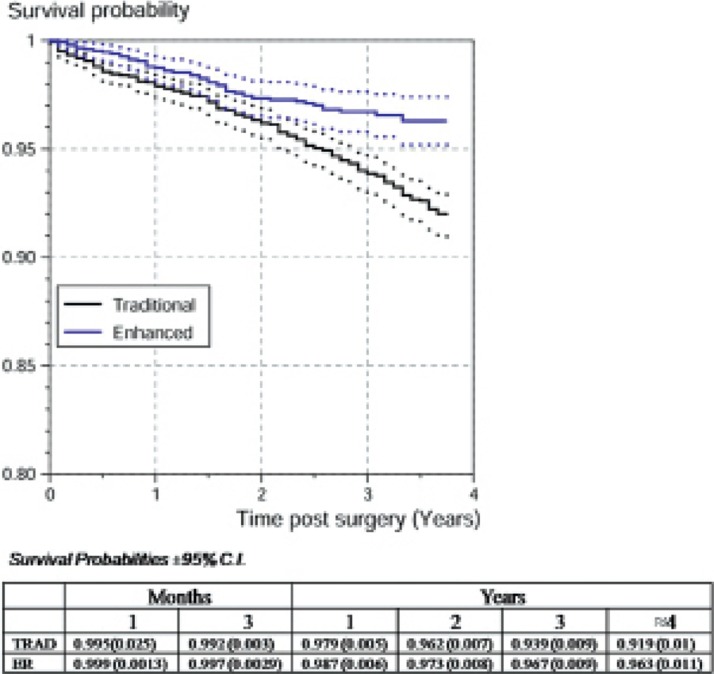

After initiation of the ER program, the mortality rate following primary hip and knee arthroplasty was reduced (p = 0.05) at 2 years (Table 2). With time (up to 3.7 years), the difference in mortality appeared to increase as the K-M survival curves diverged (χ2log-rank = 16, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of mortality rates in the two groups

| TRAD (n = 3,000) |

ER (n = 1,500) |

p-value (chi-squared test) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dead by 1 year | 63 (2.1%) | 19 (1.3%) | 0.05 |

| Dead by 2 years | 114 (3.8%) | 40 (2.7%) | 0.05 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier (K-M) survival curves for both groups ± 95% Greenwood confidence interval (dotted lines). Note that the two K-M survival curves fall outwith the ± 95% Greenwood confidence intervals. The level of significance is 0.05.

In the ER group, with a sample size that was half that of the TRAD group, it could be expected that the number of deaths at different intervals postoperatively would be half that of the TRAD group. With time, the difference in mortality appeared to increase; there were 12 fewer deaths than expected in the ER group at 1 year and this increased to 17 fewer deaths at 2 years in the ER cohort of 1,500 patients. Although fewer patients in the ER group had 3.7-year follow-up, the projected difference at that point was 5% (75 patients).

From case notes and ONS data, we were unable to ascertain the cause of death of 9 patients in the TRAD group and of 7 patients in the ER group.

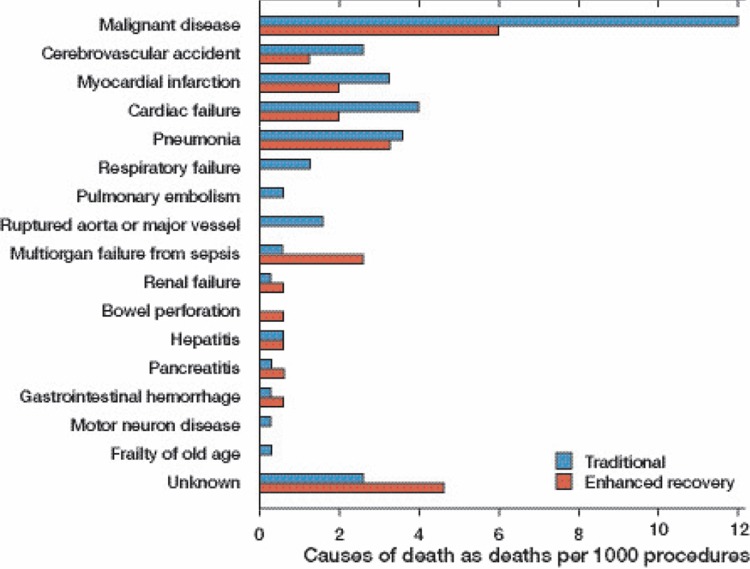

The cause of death data (Figure 2) show that at 2 years after surgery, a greater proportion of deaths were related to malignant disease in the TRAD group than in the ER group. Almost half of the patients who died due to malignant disease within 2 years in the ER group (4 of 9) had a known diagnosis of cancer prior to arthroplasty surgery. In the TRAD group, approximately one third of deaths from malignant disease (14 of 36) were in patients who were known to have developed cancer before joint replacement surgery. When K-M survival probability graphs were plotted for both groups after exclusion of all deaths that had been due to malignant disease, there were divergent curves (χ2log-rank = 11, p < 0.001), indicating that a survival benefit remained up to 3.7 years after surgery for patients who underwent an ER protocol.

Figure 2.

Cause of death for patients who died up to 2 years post surgery, reported as a rate per 1,000 procedures.

Discussion

The ER program is intended to facilitate an early return to function by minimizing stress-induced organ dysfunction after major surgery and its associated morbidity (Kehlet and Wilmore 2002).

Implementation of the ER program appeared to have a positive effect on reducing patient mortality following lower limb arthroplasty; this persisted up to 3.7 years postoperatively. The reason for this prolonged and apparently increasing beneficial effect is not known, but it may relate to the reduced stress response, shorter hospital stay, and improved pain control in the ER program group (Kehlet and Wilmore 2002, McDonald et al. 2011). With the initiation of an ER program in our unit, there was a statistically significant decrease in the postoperative transfusion rate. In contrast, in the TRAD group, there tended to be a greater range of complications—which included return to theater, hospital re-admission, stroke, myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, and thromboembolic events—within the first 2 postoperative months (Malviya et al. 2011). A recent review of prospectively collected multicenter data from over 100,000 patients who had undergone surgical procedures (a proportion of whom had THRs) showed that the occurrence of a postoperative complication within the first 30 days reduced median patient survival at 5 years, independently of patient risk preoperatively (Khuri et al. 2005). The authors suggested that the presence of an inflammatory response related to the postoperative complication may have been a contributory factor to the reduced longer-term survival. Likewise, the reduced 30-day postoperative complication incidence in the ER group in our study may explain the improved longer-term survival. In addition, the stated aim of ER programs—to use multimodal strategies to reduce the surgery-mediated inflammatory stress response (Kehlet and Wilmore 2008)—may in itself contribute to improved longer-term survival.

There has been an increase in detection rates, possibly related to better patient awareness, and there have also been improvements in treatment modalities for the most common malignant diseases in the United Kingdom, namely prostate cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer. The benefits gained from these are evident from the steady increase in 1-year survival rates after diagnosis of a malignant disease over the last 5 years (CancerResearchUK.org, accessed Aug 8. 2012). This may partly explain the higher proportion of deaths related to malignant disease in the TRAD group, which was the historical cohort. Furthermore, there is some evidence in the literature to suggest an increase in recurrence of malignant disease after blood transfusion (Blajchman 2005). The rates of malignant disease before surgery in the ER and TRAD groups were similar, but mortality due to malignant disease within 2 years post surgery was greater in the TRAD group. As the ER group had a lower postoperative transfusion rate (Malviya et al. 2011), this may have been a factor in the observed rate of deaths due to malignancy in our study.

The proportion of deaths related to the more commonly encountered post-surgical complications such as stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac failure, pneumonia, respiratory failure, pulmonary embolism, and renal failure was greater in the TRAD group.

This is the first observational study to specifically assess medium-term mortality in a large number of patients before and after the implementation of an ER program for hip and knee arthroplasty. We found a survival benefit in the longer term following implementation of the ER program. The cause of this survival benefit is still not known, but the present study further supports the routine use of ER programs for hip and knee replacement.

Acknowledgments

TS collected the data and prepared the manuscript. KM, AM, and SK collected the data and IS-P analyzed them. MRR prepared and implemented the enhanced recovery protocol, and prepared the manuscript.

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of all contributing surgeons, anesthetists, theater practitioners, nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and managers working in the orthopedic service at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, without whose help and constant support the protocol used in this study could not have been implemented.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Andersen KV, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Haraldsted V, Soballe K. Reduced hospital stay and narcotic consumption, and improved mobilization with local and intraarticular infiltration after hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial of an intraarticular technique versus epidural infusion in 80 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):180–6. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blajchman MA. Transfusion immunomodulation or TRIM: what does it mean clinically? Hematology (Suppl 1) 2005;10:208–14. doi: 10.1080/10245330512331390447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. The logrank test. BMJ. 2004;328(7447):1073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7447.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CancerResearchUK (Accessed 8 Aug 2012): CancerStats UK http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/keyfacts/ http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/keyfacts/

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Hoboken: NJ. J.Wiley; 2003. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, et al. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(9):1185–91. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Lunn TH, Troelsen A, et al. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop. 2011;82(6):679–84. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183(6):630–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):189–98. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817f2c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, et al. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):326–43. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, Sorensen OG, Hansen TB, et al. Accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation intervention for hip and knee replacement is effective: a randomized clinical trial involving 87 patients with 3 months of follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):149–59. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, et al. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(5):577–81. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.618911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DA, Siegmeth R, Deakin AH, et al. An enhanced recovery programme for primary total knee arthroplasty in the United Kingdom—follow up at one year. Knee. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.012. In Press. DOI: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly KA, Beard DJ, Barker KL, et al. Efficacy of an accelerated recovery protocol for Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty--a randomised controlled trial. Knee. 2005;12(5):351–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]