Abstract

A periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is the preferred joint preserving treatment for young adults with symptomatic hip dysplasia and no osteoarthritis. In symptomatic dysplasia of the hip, there is labral pathology in up to 90% of cases. However, no consensus exists as to whether a labral tear should be treated before the periacetabular osteotomy (PAO), treated simultaneously with the PAO, or left alone and only treated if symptoms persist after the PAO. This review is an update of aspects of labral anatomy and function, the etiology of labral tears in hip dysplasia, and diagnostic assessment of labral tears, and we discuss treatment strategies for coexisting labral tears and hip dysplasia.

Labral tearing is recognized as a cause of hip pain. In the first reports in the 1950s of labral tearing, trauma was reported as being the cause of the tear. Today, there is consensus that labral tearing rarely exists without bony malformation, and several authors have reported labral injury in relation to different pathomorphologies.

Tears are present in up to nine-tenths of symptomatic dysplastic hips. Considering both labral tears and hypertrophy of the labrum, only 5 hips in a cohort of 73 hips were found to be intact (Ross et al. 2011). Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is the preferred treatment worldwide for dysplasia of the hip, but whether a coexisting acetabular labral tear should be treated before the PAO, at the time of PAO, or after PAO if symptoms persist is still debated.

The purpose of this review is to give an update on aspects of the labral anatomy and function, the etiology of labral tears in hip dysplasia, and diagnostic assessment of labral tears, and to discuss treatment strategies for coexisting labral tearing and hip dysplasia.

Anatomy and function of the labrum

The labrum is a triangular fibrocartilagenous structure attached to the rim of the acetabulum. It runs like a horseshoe round the acetabulum, with the ends connected to each other inferiorly by the transverse ligament, thereby increasing the depth of the acetabulum, which results in extended coverage of the femoral head and enhanced joint stability (Seldes et al. 2001, Crawford et al. 2007).

Anteriorly, the labrum has a marginal attachment to the cartilage, and there is a recess between the articular surface of the acetabulum and the labrum. The collagen fibers of the labrum run parallel to the margin. The posterior region is directly attached to and continuous with the articular cartilage, and here the fibers are organized perpendicular to the margin. This histological difference may in part explain why most tears of the labrum are located anteriorly (Cashin et al. 2008).

The vascular supply to the labrum comes mainly from the hip capsule, and to some extent from the bony acetabulum (Kelly et al. 2005). The labrum is well-vascularized at the capsular side and might be capable of healing near the capsule, but the blood supply is greatly reduced throughout the labrum, leaving the parts of the labrum facing the joint avascular (Petersen et al. 2003). Free nerve endings found in the labrum suggest that the labrum is involved in pain sensation and proprioception (Kim and Azuma 1995).

In normal hips, the labrum supports 1–2% of the total load applied across the hip joint under simulation of normal walking, with the center of the femoral head achieving equilibrium near the center of the acetabulum. In developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), however, a similar simulation showed that the equilibrium achieved was at the lateral edge of the acetabulum, increasing the supporting load at the labrum to as much as 4–11% of the total load applied across the joint (Henak et al. 2011).

An intact labrum causes more equal fluid distribution during weight bearing, resulting in less cartilage deformation, low-friction articulation, and less stress across the hip joint (Ferguson et al. 2000, 2003). This is supported by the results of Song et al. (2012), who—using fresh cadavers—found higher resistance to rotation at the articular cartilage surface in hips with partial or completely removed labrum than in hips with an intact labrum.

Etiology and presentation of labral tears in hip dysplasia

Labral tearing rarely exists without bony malformation (Wenger et al. 2004, Dolan et al. 2011). In hip dysplasia, repeated micro-trauma to the labrum in the relatively unstable dysplastic hip joint is thought to cause tearing of the labrum. This may be followed by cartilage delamination and the development of osteoarthritis (McCarthy et al. 2001). Up to nine-tenths of patients with a labral defect have an associated cartilage defect (Neumann et al. 2007). The typical labrum in dysplastic hips is bulbous or hypertrophied, due to the lack of osseous containment and the continually increased joint load forces delivered to the labrum. Also, formation of ganglia in the acetabulum has been reported (Leunig et al. 2004). Para-labral cysts are often found as a secondary sign of tears or detachments of the labrum (Klaue et al. 1991, Stelzeneder et al. 2012)

In North America and Europe, the location of the tears is in the anterior-superior quadrant in as many as nine-tenths of the cases (Fitzgerald. 1995). If posterior lesions are found, suspicion should be raised regarding the presence of a concurrent anterior lesion (McCarthy et al. 2001). 2 Japanese studies found mostly posterior located lesions, which could be due to different lifestyles (Ikeda et al. 1988, Hase and Ueo 1999).

Diagnosis of labral lesions and hip dysplasia

The strong association between hip dysplasia and labral pathology is illustrated in the clinical situation. Both conditions begin often begin insidious pain, frequently located in the groin, without necessarily involving a traumatic event (Burnett et al. 2006). Mechanical symptoms like clicking, locking, and giving away have been reported to be present in more than half of the patients with a labral tear (Farjo et al. 1999), and in a hip dysplasia cohort it was reported that all patients complained of some mechanical symptom (Nunley et al. 2011).

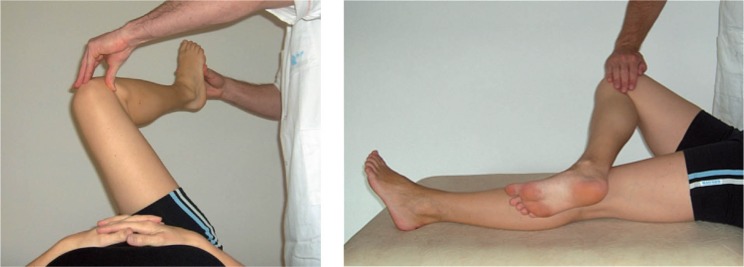

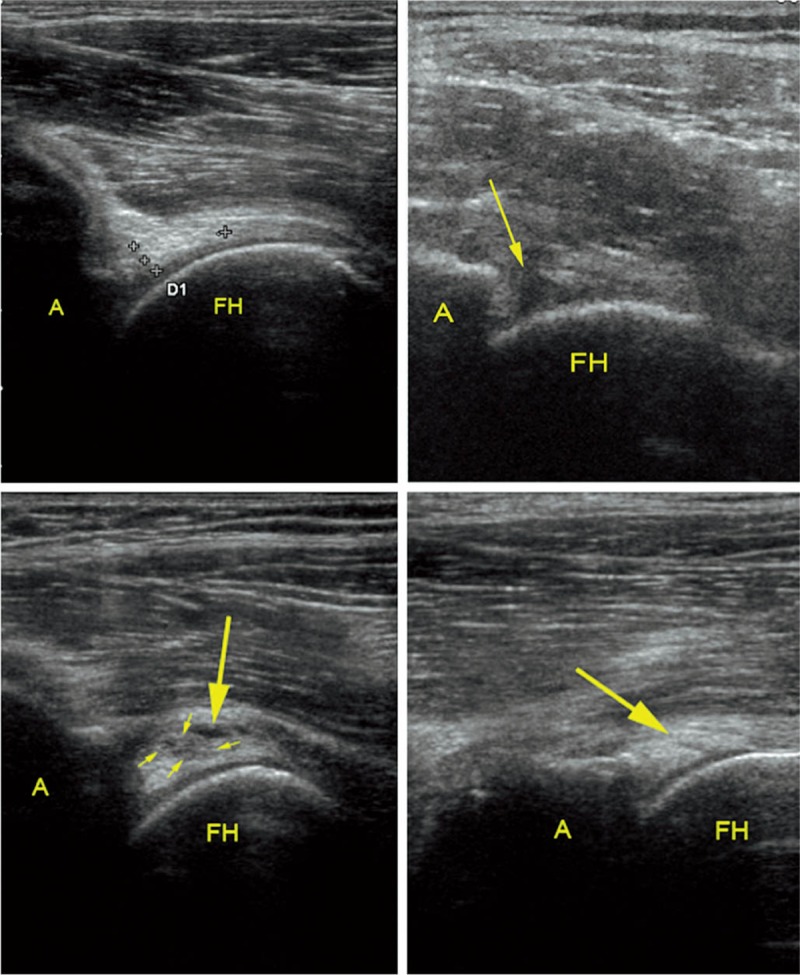

The impingement test and the FABER (Flexion, ABduction, and External Rotation) test are frequently used to diagnose a labral tear (Figure 1). The reliability of these tests is unclear. Burnett et al. (2006) and Kappe et al. (2012) reported that the impingement test was positive in 92–95% of patients having a labral tear. Narvani et al. (2003) reported that 3 of 4 patients with labral tears that were confirmed on magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) disliked the maneuver “internal rotation, flexion, and axial compression”, but so did 8 out of 14 patients without a tear. Troelsen et al. (2009b) compared 3 clinical tests with MRA and ultrasound (US) results. MRA and US were found to be superior to the 3 clinical tests, and even the most reliable clinical test (the impingement) had a sensitivity of only 59%. In experienced hands, ultrasound is reliable for detection of labral tears, but there is a substantial learning curve (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Demonstration of (a) the impingement test, performed by passively moving the hip joint into 90o of flexion, internal rotation, and adduction, and (b) the FABER test. Both tests are considered positive if groin pain is produced (Reproduced with permission from Troelsen et al., Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (3): 314-8).

A: acetabulum; FH: femoral head.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound examination of the acetabular labrum. A. A normal labrum. The crosses mark the base and the apex of the labrum (“D1” marking is automatically supplied with the crosses). B. An acetabular labral tear with detachment (arrow). C. A labral tear with intra-substance cystic formation (large arrow) and a slightly irregular hypoechoic cleft (small arrows). D. An intra-substance linear labral tear (arrow). (Reproduced with permission from Troelsen et al., Acta Radiol 2007; 48: 1004-10).

Burnett et al. (2006) found that 20 of 22 patients with tears felt relief of symptoms after intraarticular injections with local anesthetic.

Radiology

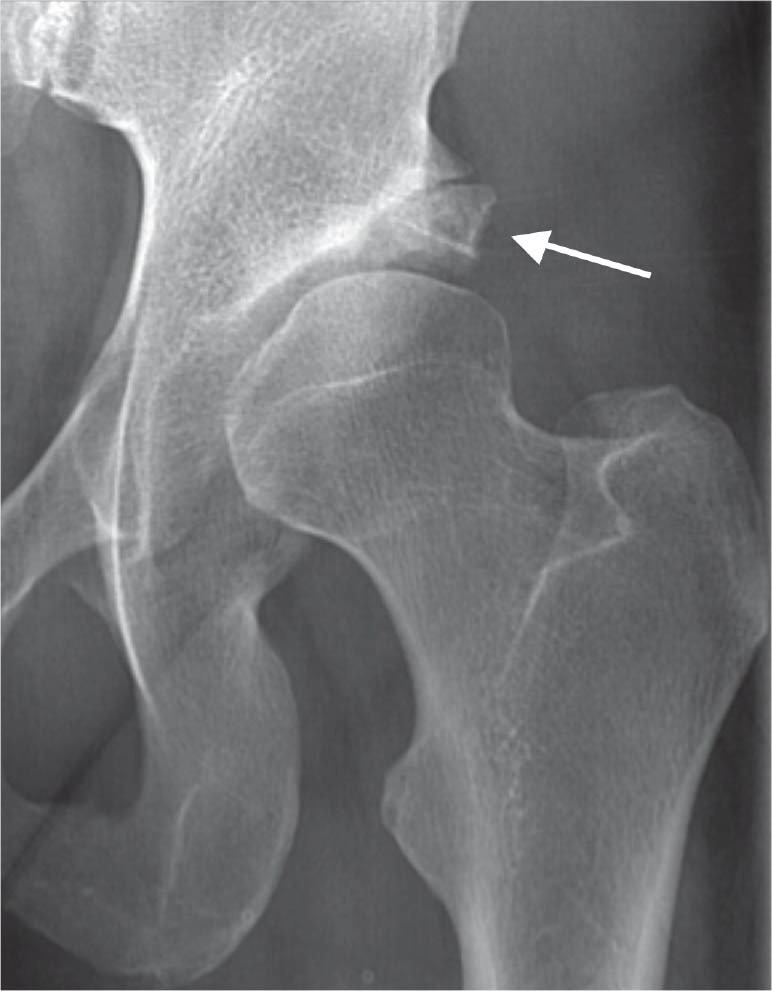

By conventional radiography in 2 planes (anteroposterior pelvic and lateral hip view), hip dysplasia is characterized by a reduced center-edge angle of Wiberg (1939) (< 25°) and an increased acetabular index angle of Tönnis (1987) (> 10°). An os acetabuli may indicate tearing of the labrum and overload of the acetabular rim (Klaue et al. 1991) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A dysplastic hip, with arrow showing a large os acetabuli or rim fractures.

Computed tomography (CT) effectively presents the 3-dimensional bony pathomorphology of the hip joint. CT arthrography is reliable in labral diagnostics, but it exposes the patient to high doses of radiation (Yamamoto et al. 2007).

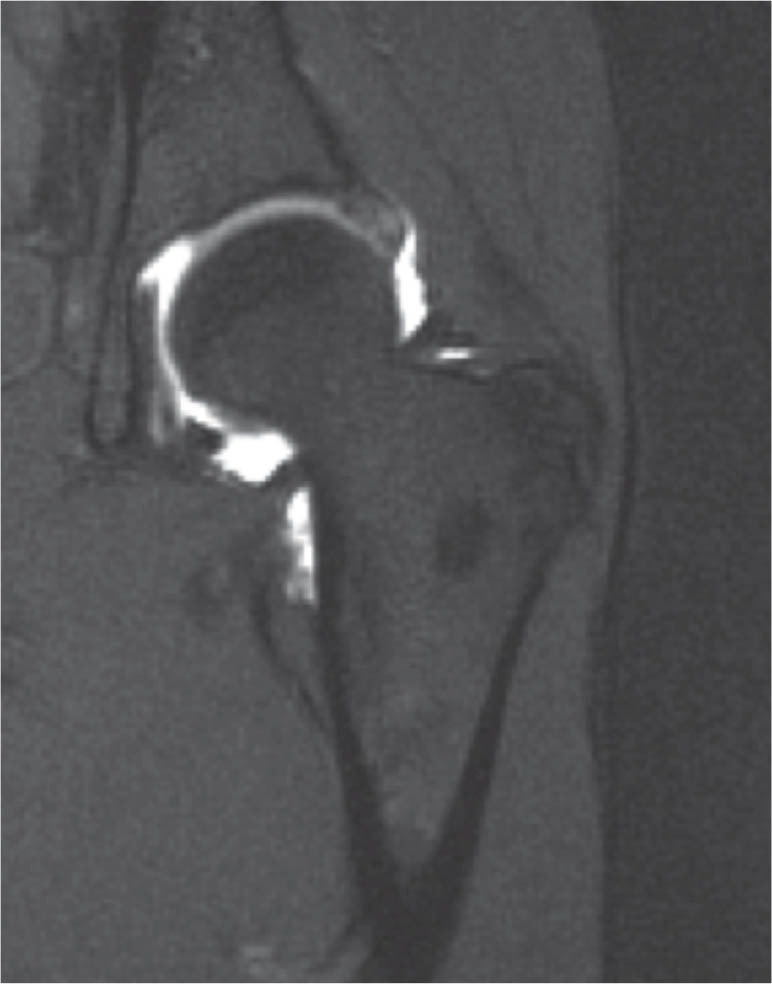

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and direct or indirect MRA are used extensively to diagnose intraarticular hip joint pathology. The reliability of MRA is superior to that of MRI for diagnosis of tears and degenerative changes (Toomayan et al. 2006, Ziegert et al. 2009) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Coronal section MR arthrography of a dysplastic hip. The labrum is hypertrophic and contrast medium is running through the base of the labrum, an indication that the labrum is detached from the acetabular rim.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the normal hip joint and of inter-individual variations is necessary for interpretation of MRA. Age causes changes in signal intensity and shape. The labrum might be absent and a sulcus or cleft might simulate a tear (Abe et al. 2000, Studler et al. 2008, Rakhra 2011).

Treatment of labral tears in dysplastic hips

Today, there is a general consensus that the optimal treatment of hip dysplasia is a PAO, and most surgeons agree that labral surgery alone is not sufficient. How one should treat coexisting acetabular labral pathology is still the subject of debate, however.

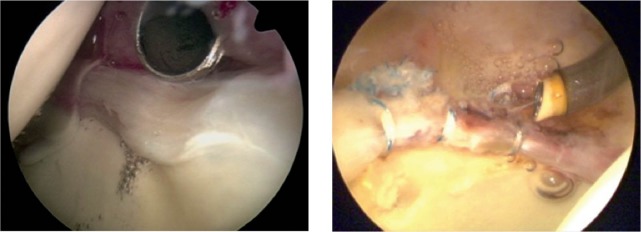

There is no strong evidence for the optimal treatment of intraarticular pathology together with hip dysplasia (Appendix; see Supplementary data). Most studies pertaining to the treatment of labral tears have been retrospective, and have dealt with FAI (femoroacetabular impingement) cases. These studies have been characterized by limited patient material and only short follow-up. The literature indicates that the labrum should be preserved if possible, and reports have shown superior outcome if the labrum is refixed rather than excised (Figure 5). By preserving the labrum, continued stability of the hip and the sealing function of the labrum might reduce and delay the development of osteoarthritis in the hip.

Figure 5.

Arthroscopic pictures illustrating (a) a detached labrum with wave sign and synovitis, and (b) a labrum re-attached to the acetabular rim with 3 suture anchors. (The images were kindly provided by the Department of Sports Traumatology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark).

Matheney et al. (2009) found that the presence of a labrum lesion was not a prognostic factor for failure following PAO, and accordingly, they did not perform an arthrotomy routinely. Matta et al. (1999) changed from open inspection of the hip joint and labrum to only performing the PAO, relying on the hypothesis that the PAO normalizes load distribution in the hip joint. Troelsen et al. (2009a) found their 5.2- to 9.2-year results after PAO to be comparable to those in the existing literature using the minimally invasive technique without capsule opening. However, in their study the status of the acetabular labrum was unknown, and there was no control group.

Conclusion

There is no evidence in the literature to suggest the optimal treatment strategy for labral pathology in dysplastic hips. The diagnosis of clinically significant labral tears in dysplastic hips remains a challenge, and to complicate the issue further, labral abnormalities are commonly also found in asymptomatic individuals. In the literature, a high prevalence of labral pathology in hip dysplasia is described, but whether or not labral pathology should be treated with open arthrotomy with a view to performing the PAO or arthroscopicly at a later stage if symptoms persist remains unknown. At present, it does not seem justifiable to routinely perform arthrotomy during PAO. Since most patients with hip dysplasia are likely to have labral pathology, and since several studies have shown excellent survival of the hip following PAO without prior arthroscopy or intraoperative arthrotomy, we recommend that only PAO be performed. The PAO will normalize the stress delivered at the acetabular rim, and to the labrum. Patients with continued hip pain after PAO related to labral pathology can then be referred for arthroscopic treatment.

Supplementary data

Appendix is available at our website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 5645.

Acknowledgments

CHA: writing of the review. CHA, AT, and KSØ: revision and final approval of the review.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Abe I, Harada Y, Oinuma K, et al. Acetabular labrum: Abnormal findings at MR imaging in asymptomatic hips. Radiology. 2000;216(2):576–81. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett RS, Della Rocca GJ, Prather H, et al. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(7):1448–57. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1055–60. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy for labral pathology: Prospective analysis with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):365–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashin M, Uhthoff H, O’Neill M, Beaule PE. Embryology of the acetabular labral-chondral complex. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90(8):1019–24. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MJ, Dy CJ, Alexander JW, et al. The 2007 frank stinchfield award. the biomechanics of the hip labrum and the stability of the hip. Clin Orthop. 2007;(465):16–22. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31815b181f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan MM, Heyworth BE, Bedi A, et al. CT reveals a high incidence of osseous abnormalities in hips with labral tears. Clin Orthop. 2011;469(3):831–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farjo LA, Glick JM, Sampson TG. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):132–7. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.015013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K. The influence of the acetabular labrum on hip joint cartilage consolidation: A poroelastic finite element model. J Biomech. 2000;33(8):953–60. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech. 2003;36(2):171–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald RH., Jr Acetabular labrum tears. diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1995;(311):60–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase T, Ueo T. Acetabular labral tear: Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):138–41. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henak CR, Ellis BJ, Harris MD, et al. Role of the acetabular labrum in load support across the hip joint. J Biomech. 2011;44(12):2201–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Awaya G, Suzuki S, et al. Torn acetabular labrum in young patients. arthroscopic diagnosis and management. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1988;70(1):13–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B1.3339044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain MS, Novais EN, Vallim C, et al. Periacetabular osteotomy after failed hip arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2011;93:57–61. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappe T, Kocak T, Reichel H, Fraitzl CR. Can femoroacetabular impingement and hip dysplasia be distinguished by clinical presentation and patient history? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):387–92. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BT, Shapiro GS, Digiovanni CW, et al. Vascularity of the hip labrum: A cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YT, Azuma H. The nerve endings of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop. 1995;(320):176–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991;73(3):423–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leunig M, Podeszwa D, Beck M, et al. Magnetic resonance arthrography of labral disorders in hips with dysplasia and impingement. Clin Orthop. 2004;(418):74–80. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheney T, Kim YJ, Zurakowski D, et al. Intermediate to long-term results following the bernese periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of clinical outcome. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009;91(9):2113–23. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta JM, Stover MD, Siebenrock K. Periacetabular osteotomy through the smith-petersen approach. Clin Orthop. 1999;363(363):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, et al. The otto E. aufranc award: The role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop. 2001;(393):25–37. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvani AA, Tsiridis E, Kendall S, et al. A preliminary report on prevalence of acetabular labrum tears in sports patients with groin pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11(6):403–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Mendicuti AD, Zou KH, et al. Prevalence of labral tears and cartilage loss in patients with mechanical symptoms of the hip: Evaluation using MR arthrography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(8):909–17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunley RM, Prather H, Hunt D, et al. Clinical presentation of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in skeletally mature patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2011;93:17–21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Bican O, Bender B, et al. Arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: A cautionary note. J Arthroplasty (6 Suppl) 2009;24:110–13. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CL, Erickson JA, Hines JL. Early results of the bernese periacetabular osteotomy: The learning curve at an academic medical center. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(9):1920–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen W, Petersen F, Tillmann B. Structure and vascularization of the acetabular labrum with regard to the pathogenesis and healing of labral lesions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123(6):283–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhra KS. Magnetic resonance imaging of acetabular labral tears. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2011;93:28–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JR, Zaltz I, Nepple JJ, et al. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med (39 Suppl) 2011. pp. 72S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Seldes RM, Tan V, Hunt J, et al. Fitzgerald RH., Jr Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop. 2001;(382):232–40. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Ito H, Kourtis L, et al. Articular cartilage friction increases in hip joints after the removal of acetabular labrum. J Biomech. 2012;45(3):524–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzeneder D, Mamisch TC, Kress I, et al. Patterns of joint damage seen on MRI in early hip osteoarthritis due to structural hip deformities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(7):661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studler U, Kalberer F, Leunig M, et al. MR arthrography of the hip: Differentiation between an anterior sublabral recess as a normal variant and a labral tear. Radiology. 2008;249(3):947–54. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492080137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelsen A, Elmengaard B, Soballe K. Medium-term outcome of periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of conversion to total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009a;91(9):2169–79. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelsen A, Mechlenburg I, Gelineck J, et al. What is the role of clinical tests and ultrasound in acetabular labral tear diagnostics? Acta Orthop. 2009b;80(3):314–8. doi: 10.3109/17453670902988402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnis D. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. New York: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Toomayan GA, Holman WR, Major NM, et al. Sensitivity of MR arthrography in the evaluation of acetabular labral tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(2):449–53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger DE, Kendell KR, Miner MR, Trousdale RT. Acetabular labral tears rarely occur in the absence of bony abnormalities. Clin Orthop. 2004;(426):145–50. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136903.01368.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg G. Studies an dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint with special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand (Suppl 58) 1939;83:5–135. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Tonotsuka H, Ueda T, Hamada Y. Usefulness of radial contrast-enhanced computed tomography for the diagnosis of acetabular labrum injury. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(12):1290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegert AJ, Blankenbaker DG, De Smet AA, et al. Comparison of standard hip MR arthrographic imaging planes and sequences for detection of arthroscopically proven labral tear. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1397–400. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.