Abstract

There is an emerging body of research demonstrating that the co-expression of key lineage-specifying transcription factors, commonly referred to as ‘master regulators’, impacts the functional capabilities and flexibility of CD4+ T cell subsets. Here, we discuss how the natural co-expression of these lineage-specifying transcription factors has challenged the concept that the expression of a single ‘master regulator’ strictly establishes an absolute CD4+ T cell phenotype. Instead, it is becoming clear that the interplay between the lineage-specifying (or lineage-defining) transcription factors, including T-bet, GATA3, RORγt, BCL6 and FOXP3, contributes to the fate and flexibility of CD4+ T cell subtypes. This in turn has led to the realization that CD4+ T cell phenotypes are more diverse than previously recognized.

The complex series of events that are required to establish unique, cell-type specific gene expression programmes are truly amazing. One just has to take a step back and remember that the information encoded in the DNA is the same in all cell types, yet the reading and processing of this information is specific to individual cells as well as to the response of those cells to changing environmental conditions. There are many layers of control that must be precisely coordinated to establish developmentally appropriate gene expression patterns and even small alterations can have severe consequences on the fate of the cell1–4. This is powerfully illustrated by the plethora of human diseases that can be traced back to mutations in transcriptional regulatory proteins5–7.

This complexity can be daunting for the researchers that are trying to understand cellular differentiation unless mechanistic questions are first broken apart into smaller, discrete problems. It is imperative to begin somewhere, and a common starting point is defining the complement of transcription factors that are required for a unique cell fate decision. In common terminology, this first step is determining the ‘master regulators’ for a cell fate. The simplified paradigm of the master regulator relies on the premise that each developmental cell type is defined by a critical transcription factor. This means that there is a transcription factor that is both required and sufficient for programming an individual cell fate. Another aspect of this paradigm is that the master regulator is expressed in a restricted expression pattern, which means that in a particular developmental lineage, it is only found in cells of a specific fate. Finally, to be classified as a master regulator, these transcription factors need to come from families that are important in different developmental contexts and mutations in these proteins often cause developmental defects.

In this Opinion article, we will briefly examine how the ‘master regulator’ terminology has shaped our thought process in relation to CD4+ T cell subset differentiation. Specifically, thinking of the key lineage-specifying transcription factors for specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes in terms of the master regulator paradigm caused the impression that the expression of a single ‘master regulator’ transcription factor unilaterally created absolute and stable CD4+ T cell subtypes. However, recent studies have instead demonstrated that the co-expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors in CD4+ T cell subsets actually creates flexibility and diversity of CD4+ T cell phenotypes. The current state of the field now suggests that the simplistic paradigm of a single master regulator transcription factor that applies to stable developmental decisions, such as with the requirement for ThPOK in the commitment between the CD4+ versus CD8+ T cell fate8, may not so neatly apply to the more flexible differentiation pathways of specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes.

Defining the ‘master regulators’

In the CD4+ T cell differentiation field, a substantial effort was put into identifying the critical transcription factors that are required for the differentiation of each helper T cell fate. For instance, the T-box transcription factor T-bet was identified as the factor that is required and sufficient to induce the T helper 1 (Th1)-type gene expression programme9, 10. Early studies also found that T-bet expression was restricted to Th1 cells when examining canonical helper T cell differentiation conditions in vitro or when examining immune responses to pathogens that induce strong Th1-type polarizing conditions in vivo9–11. Additionally, T-bet is a member of the T-box transcription factor family, which is required for many developmental cell fate decisions12. Taken together, these data led to the identification of T-bet as the ‘master regulator’ transcription factor for Th1 cell differentiation9. Similar research efforts defined the transcription factors GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3), retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-γt (RORγt), B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) and forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) as ‘master regulators’ for Th2, Th17, T follicular helper (Tfh) and T regulatory (Treg) cells, respectively13–19. These collective groundbreaking studies contributed to our early understanding of CD4+ T cell responses and created a basis to form new hypotheses to predict the immune responses that occur when environmental conditions promote the expression of each of these transcription factors.

Beyond the ‘master regulator’ paradigm

Although it was important to start with identifying the critical lineage-specifying transcription factors required for the differentiation of specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes, the term ‘master regulator’ may have unintentionally created the impression that helper T cell differentiation is dependent upon an absolute hierarchy of control that results in a preordained phenotype (see Box 1). Reflecting this thought process, perhaps the most common assumption that comes to mind with the terminology ‘master regulator’ is that expression equals phenotype. For example, the expression of T-bet in CD4+ T cells has been equated with a canonical Th1 cell phenotype, whereas the expression of BCL6 would equal a canonical Tfh cell phenotype9, 16–18. The biggest pitfall of this underlying assumption can be unintentionally missing the complexity of the CD4+ T cell response by focusing on the expression of only one transcription factor. Notably, it is becoming apparent that the expression of a single ‘master regulator’ transcription factor is not sufficient to define the phenotype of a CD4+ T cell subtype; instead, it is the context of its expression that is critical20–22. Nowhere is this concept more apparent than in the emerging data in the field demonstrating that the lineage-specifying transcription factors that define CD4+ T cell subsets are actually co-expressed in many circumstances, and in fact, it is the interplay between these factors that determines the final outcome on the gene expression profile (and phenotype) of CD4+ T cells. Importantly, this phenomenon has been observed with the co-expression of T-bet and GATA3, RORγt, or BCL6 in CD4+ T cells as well as with FOXP3 and T-bet, STAT3, GATA3, RORγt or BCL6 in specialized Treg cells as will be discussed below23–36.

Box 1. An unintended consequence of the master regulator terminology.

One unanticipated side-effect of the ‘master regulator’ terminology has been that the importance of other critical transcription factor families have at times been subtly diminished in the field. For instance, although T-bet is commonly termed the master regulator for T helper 1 (Th1) cell development, the Th1 gene-expression programme also requires a number of other transcriptional regulatory proteins, most notably signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT452–59. In reality, the roles that STAT1 and STAT4 play in establishing a Th1 cell-associated gene-expression programme are of equal importance to the role of T-bet. Associated with this same point, many more ubiquitously expressed proteins also play essential roles in helper T cell differentiation and we have yet to fully appreciate their significance in many settings60–63. Sometimes these other transcriptional regulators are lost in our focus on the role of the ‘master regulator’ of a cell lineage. Together with our new recognition that the co-expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors creates a greater diversity of CD4+ T cell phenotypes than previously recognized, we also need to be sure to incorporate the complexity derived from additional required regulatory factors operating in these cells as well. With expanding capabilities in genomics and proteomic experimental approaches becoming increasingly available to researchers, a more detailed integration of the network of transcriptional regulatory proteins that are required to create the diversity of CD4+ T cell subtypes during the course of a natural immune response may now be a more achievable goal41, 46, 47, 64.

Transient versus stable co-expression

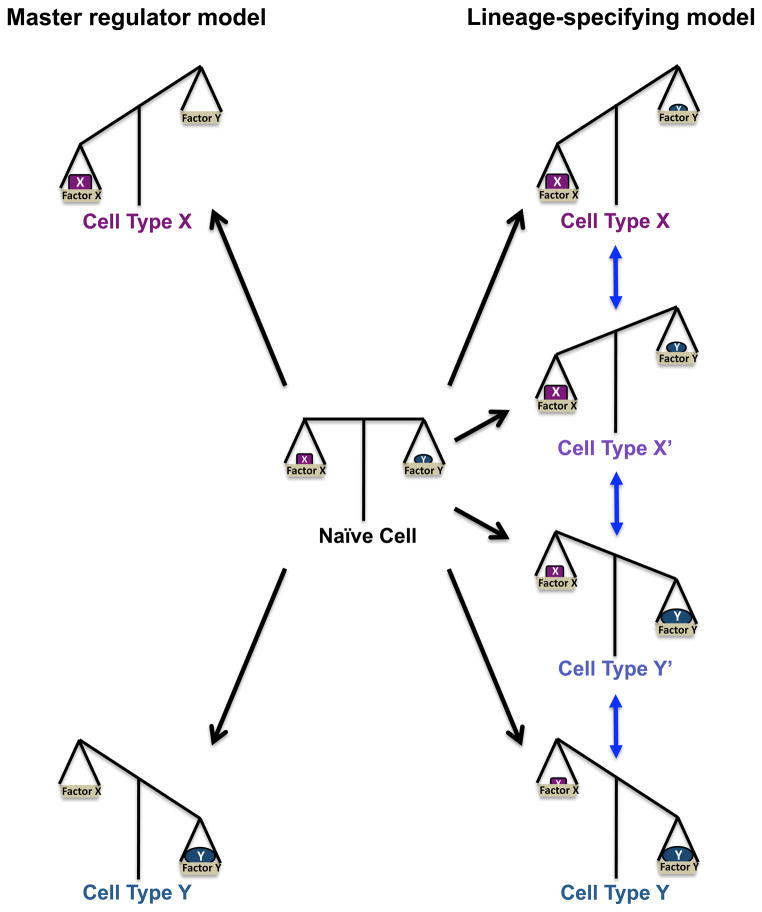

Many of the early studies that first reported the co-expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors in CD4+ T cells described a transient co-expression of these key factors during the early stages of the commitment of CD4+ T cells into specialized subtypes. In these circumstances, co-expression creates a scenario where environmental signals can tip the balance of expression in favor of one factor or the other (Fig. 1). This allows the signals generated from the innate immune response to a pathogen to select one factor, pushing the CD4+ T cell down the ‘winning’ factors commitment pathway. Studies demonstrating that a competition between T-bet and GATA3 occurs as CD4+ T cells begin to commit towards the Th1 or Th2 lineage were consistent with the idea that the transient co-expression of these factors can play a competitive and antagonistic role in the lineage-commitment process26. Studies examining FOXP3 and RORγt also supported the concept that initial CD4+ T cell subtype commitment decisions are affected by the balance between two lineage-specifying transcription factors34, 35.

Figure 1. Co-expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors tips the balance in CD4+ T cell gene programmes.

Shown is a representation depicting scales illustrating how the balance between the co-expression of key transcription factors creates diversity of CD4+ T cell phenotypes. In naïve CD4+ T cells, critical lineage-specifying transcription factors are expressed at low levels and are kept in an equal balance. Signals from innate immune cells tip the scales in favor of the expression of one factor over the other. In the paradigm of the master regulator, the scales are tipped in an ‘all-or-none’ fashion, with the expression of one master regulator increasing, while the expression of the opposing master regulator will be extinguished (left side). However, new research demonstrating that lineage-specifying transcription factors are co-expressed, creating diverse CD4+ T cell phenotypes, has changed our concept of this simple paradigm (right side). In this new model termed ‘lineage-specifying’, the co-expression of the ‘lineage-defining’ or ‘lineage-specifying’ transcription factors can tip the scales to variable levels, causing intermediate phenotypes (X″ and Y″), in addition to the phenotypes that were previously viewed as endpoint lineages (X and Y). Additionally, as the balance of co-expression changes in response to environmental signals, this can create flexibility or plasticity between the intermediate phenotypes.

These early observations were still consistent with a ‘master regulator’ transcription factor playing the role of an absolute determinant for CD4+ T cell subset fate because their co-expression was transient, creating a competitive environment that would be quickly resolved by external cues generated by innate immune cells. However, recent data from many independent laboratories, examining CD4+ T cell differentiation both in vitro and in vivo, have observed stable co-expression of the helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors in committed CD4+ T cell subset populations24, 25, 27–30, 33, 36, 37. These studies have also revealed more complexity in the gene expression programmes and phenotypes of CD4+ T cells than previously appreciated, with current data suggesting that changing environmental conditions can alter the underlying potential of CD4+ T cell subtypes and allow for flexibility or plasticity in their responses38. Taken together, these studies have now raised the question of how the stable co-expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors impacts the gene expression programme and phenotype of CD4+ T cells.

Specialized Treg cell populations

A well-recognized example demonstrating a functional role for the stable co-expression of two seemingly opposing lineage-specifying transcription factors can be found in specialized Treg cell populations39, 40. Here, the simultaneous expression of FOXP3 with T-bet, GATA3, STAT3 or BCL6 has been linked to the ability of regulatory T cells to suppress Th1, Th2, Th17 or Tfh cell responses, respectively23, 24, 27, 28, 33. The current data in the field have clearly shown that the simultaneous expression of both FOXP3 and an additional helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factor is necessary for regulatory T cells to functionally control specialized immune responses. An intriguing aspect of this example is that one of the lineage-specifying transcription factors, FOXP3, is dominant in creating the inherent properties of the cell. That is, the gene expression profile of the cell is still predominantly characterized by the FOXP3-dependent induction of a regulatory T cell gene-expression programme, with the stable co-expression of the additional lineage-specifying factor subtly shifting the homing properties of the Treg cell24, 27, 28. Thus, although a somewhat hybrid gene-expression programme representing the combined activities of FOXP3 and the additional lineage-specifying factor is created, the FOXP3-dependent regulatory programme dominates the functional characteristics of the cell. Ongoing research is actively defining the mechanisms by which FOXP3 establishes these hybrid gene expression profiles (Box 2). Interestingly, a recent study using a proteomics approach to this topic suggests that at least some of the hybrid nature of the regulatory T cell gene programme may be mediated by the physical interactions between FOXP3 and a subset of helper T cell lineage-specifying factors41.

Box 2. Molecular mechanisms that define specialized Treg cell subsets.

Even though the co-expression of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) and an additional lineage-specifying transcription factor is required to create specialized Treg cell suppressor programmes, a number of mechanistic studies also have suggested that additional regulatory proteins play crucial roles in this process. This concept is clearly illustrated by recent studies examining type 1 diabetes and arthritis in FOXP3-GFP (green fluorescent protein) transgenic mice on different susceptibility backgrounds65, 66. These studies found that the fusion of GFP to the N-terminal domain of FOXP3 creates a hypomorphic protein that impairs, or in one case enhances, protein–protein interactions that occur within the N-terminal domain of FOXP3. Specifically, this alters the ability of FOXP3 to interact with regulatory proteins such as interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4), hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF1α) and chromatin-modifying complexes. Functionally, the extra-thymic generated (induced) Treg cells that were derived in this setting had the ability to control arthritis, but were unable to control type 1 diabetes. These data suggest that protein–protein interactions mediated through the N-terminal domain of FOXP3 are required to create unique subtypes of functionally specialized Treg cells. Future research examining how specialized Treg cell functions are influenced by the co-expression of opposing lineage-specifying transcription factors, as well as by these other regulatory proteins, will be of great interest.

‘Th2+1’: GATA3 and T-bet co-expression

It has long been established that T-bet and GATA3 are transiently co-expressed in naïve helper T cells prior to the initial lineage subtype-commitment decision26. Recently, the issue of T-bet and GATA3 co-expression became more complex and now can no longer be completely explained within the context of a simple master regulator paradigm. In the setting of a normal immune response, cells that were previously defined as being ‘Th2 cells’ based upon their stable expression of GATA3 were found to upregulate T-bet in response to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection25. This caused the cell to express a hybrid gene-expression programme with characteristics of both Th1 and Th2 cells. These cells were named ‘Th2+1’ to reflect this phenomenon and they represented one of the first examples of how the natural co-expression of two opposing helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors during the course of an immune response can change the functional capabilities of helper T cells. These data also suggested that helper T cells do not fit so neatly into strictly defined endpoint lineages, but rather remain responsive to changing environmental conditions.

Th17 cell diversity and pathogenicity

The co-expression of T-bet and RORγt in helper T cell subpopulations clearly illustrates the problem of strictly interpreting the expression of T-bet or RORγt from the perspective of the master regulator paradigm. Shortly after the identification of RORγt as the ‘master regulator’ for Th17 cells, studies began to emerge demonstrating that IL-17+IFNγ+ helper T cell populations exist that stably express both T-bet and RORγt36, 42, 43. Whether helper T cells differentiating along the Th17 pathway express RORγt alone, or rather RORγt in combination with T-bet, appears to be determined by the nature of the pathogen and the cytokine environment. Studies have shown that RORγt and T-bet co-expression in ‘Th17’ cells is promoted by the absence of TGFβ1, or a shift in the cytokine environment in favor of TGFβ336, 44, 45. The co-expression of T-bet and RORγt creates a hybrid ‘Th17’ gene programme that can control certain pathogens such as C. albicans, but importantly, this programme also has a propensity to become pathogenic and cause autoimmune states36, 44, 45. Therefore, the co-expression of T-bet and RORγt provides a compelling example of the consequences for the natural co-expression of helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors in defining complex, and potentially pathogenic, helper T cell phenotypes.

Flexibility in Th1 and Tfh programmes

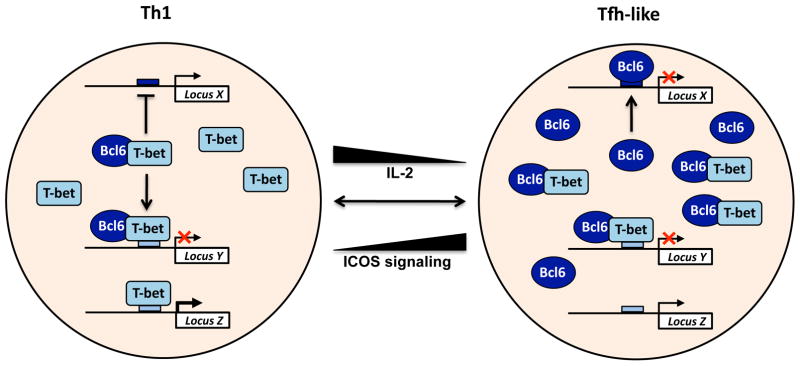

Another example for the stable co-expression of two opposing helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors is that of T-bet and BCL6 in CD4+ T cells. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that variable levels of BCL6 can be expressed in T-bet-positive ‘Th1 cells’, with BCL6 expression levels regulated in response to environmental conditions29, 30, 37, 46, 47. The current data suggest that the balance between T-bet and BCL6 co-expression is functionally important in determining the phenotype of the helper T cell and its role in the immune response. For example, in effector Th1 cells with high T-bet expression, a low level of BCL6 is also expressed29, 30, 37, and this is essential for the T-bet-dependent repression of Th2 cell-associated genes29. Interestingly, the balance between T-bet and BCL6 can be shifted in favor of BCL6 either by reducing the strength of interleukin-2 (IL-2) signaling or upregulating inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS)–ICOS ligand interactions30, 37, 48, 49. Tipping the balance towards an increased ratio of BCL6 to T-bet alters the gene-expression profile of the CD4+ T cell, and depending upon the level of BCL6, creates the potential for T central memory (TCM) cell- or Tfh cell-like gene expression characteristics30, 37.

When examining this phenomenon from the perspective of Th1 or Tfh cell differentiation, a balance between BCL6 and T-bet is also observed, with STAT4 playing a role in regulating both BCL6 and T-bet expression46,47. Here, a transitional state with dual Tfh cell-like and Th1 cell-like characteristics occurs until the balance favors either BCL6 or T-bet. Notably, epigenetic profiling studies indicate that the loci for Bcl6, Tbx21 (the gene that encodes T-bet) and Prdm1 (the gene that encodes B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP1)) are maintained in poised epigenetic states so they will remain responsive to changing environmental conditions46, 50. Collectively, the studies performed to date suggest that the co-expression of T-bet and BCL6 creates a scenario that allows helper T cells in the Th1 and Tfh subtypes to remain responsive to environmental conditions and express diverse gene-expression programmes that include more states than merely endpoint Th1 or Tfh cell phenotypes (Fig. 1).

Mechanisms that regulate co-expression

With the realization that the natural co-expression of helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors is important for defining the functional potential and flexibility of CD4+ T cells, a new area of research emphasis is determining the mechanisms by which these factors regulate each other’s activities51. Studies are underway characterizing how the lineage-specifying transcription factors functionally interact with each other in different settings to create the gene-expression programme of the CD4+ T cell subsets23, 30, 47. One important question to address is whether these factors act in a cooperative or antagonistic fashion. That is, are they collaborators, competitors or both depending upon the circumstances? The molecular mechanisms that define the interplay between T-bet and BCL6 provide one example that illustrates the complexity of this question.

T-bet and BCL6 functionally control each other’s activities in part through their physical interaction and also in part through their ability to cross-regulate each other’s expression in some circumstances17, 18, 29, 30. Early studies demonstrated that in effector Th1 cells, a T-bet–BCL6 complex specifically associates with T-bet DNA-binding elements29. Thus, T-bet is able to target BCL6 in a site-specific manner to repress genes that are important for Th2 cell development. This observation raised the question of how BCL6 activity is regulated in Th1 cells to prevent it from tipping the balance of the cell towards a Tfh cell gene-expression programme. The nature of the physical interaction between T-bet and BCL6 provided insight into this question, with the DNA-binding domain of BCL6, but not T-bet, required to mediate the physical interaction between these two proteins30. This creates a scenario where a T-bet–BCL6 complex masks the DNA-binding domain of BCL6, while leaving the T-bet DNA-binding domain available. Thus, the molecular mechanisms of this interaction explain why T-bet–BCL6 complexes are preferentially targeted to T-bet DNA-binding elements and why BCL6 is prevented from regulating its own gene-expression programme when excess T-bet is available in the cell (Fig. 2). Studies examining the physical interactions between T-bet and GATA3, as well as FOXP3 and RORγt or GATA3, have also provided unique mechanistic insights26, 35, 41. The principles uncovered in all of these studies illustrate how defining the molecular details by which CD4+ T cell subtype-specifying transcription factors influence each other’s activities will aid in our ability to predict the outcome for the co-expression of these factors in a given setting.

Figure 2. T-bet–BCL6 complexes prevent BCL6 from binding to its target genes.

Shown is a schematic representation of how the physical interaction between T-bet and BCL6 influences the activities of both proteins. T-bet–BCL6 complexes can bind to T-bet DNA-binding elements, allowing T-bet to target the repressive capabilities of BCL6 to these T-bet DNA-binding sites. In contrast, the T-bet–BCL6 complex prevents BCL6 from associating with its own DNA-binding elements because the complex masks the DNA-binding domain of BCL6. This means that the balance between T-bet and BCL6 determines where these two proteins will be functionally targeted within a cell population. Notably, environmental signaling events can regulate their expression levels, changing the balance and creating flexibility within helper T cell populations.

Summary and perspective

The examples discussed above represent only a few in this emerging area of research, with each highlighting the importance of taking a step back to re-examine our views on the simple paradigm of the master regulator in the differentiation of specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes. One aspect of this paradigm that has held up over time in relation to CD4+ T cell subtype differentiation is that a select group of transcription factors are required to define the prototypic characteristics of CD4+ T cell subsets. However, it is also now apparent that the expression of a single master regulator transcription factor alone is not sufficient to invoke an absolute, endpoint phenotype. Perhaps these findings reflect that the differentiation of specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes may not truly represent a stable developmental decision, like the stable commitment decision to either the CD4+ or CD8+ T cell lineage. Instead, it is now becoming more widely accepted that CD4+ T cell subtypes retain at least some potential to respond to changing environmental conditions to alter their underlying subtype-specific gene programmes. This may be an immunologically important characteristic of CD4+ T cells that allows them to coordinate and fine-tune the immune response in real time.

With this new recognition for the limitations of thinking about specialized CD4+ T cell subtypes through the lens of the master regulator paradigm, a subtle shift in the use of our terminology from ‘master regulator’ to ‘lineage-specifying’ or ‘lineage-defining’ transcription factor is warranted in the CD4+ T cell field. This nomenclature reflects the requirement for these transcription factors in defining CD4+ T cell subtype characteristics, but it de-emphasizes the concept of an ‘all-or-nothing’ and completely stable phenotype that is dictated by a single transcription factor (Fig. 1). This is an especially important point as the field moves forward because it is now clear that the diversity of CD4+ T cell phenotypes that arise to control specific pathogenic insults is much greater than previously thought20–22. One needs to look no further than the examples discussed here to realize that the context in which the lineage-specifying transcription factors are expressed plays a substantial role in determining the final outcome each has on the gene-expression programme of the cell. Our challenge now becomes understanding this complexity and designing experimental approaches to determine how the co-expression of two or more helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors influences gene expression programmes and how this creates the diversity that is required to establish a productive immune response to control a myriad of pathogenic insults.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Weinmann lab for lively discussions on this topic. The research in the authors’ lab is supported by grants from the NIAID (AI061061 and AI07272) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-09-045-01-DDC) to A.S.W.

References

- 1.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Epigenetics of haematopoietic cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:478–88. doi: 10.1038/nri2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–84. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lessard JA, Crabtree GR. Chromatin regulatory mechanisms in pluripotency. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:503–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-051809-102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:91–105. doi: 10.1038/nri2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. BCL6: master regulator of the germinal center reaction and key oncogene in B cell lymphomagenesis. Adv Immunol. 2010;105:193–210. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly KF, Daniel JM. POZ for effect--POZ-ZF transcription factors in cancer and development. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:578–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarevic V, Glimcher LH. T-bet in disease. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:597–606. doi: 10.1038/ni.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaulieu AM, Sant’Angelo DB. The BTB-ZF family of transcription factors: key regulators of lineage commitment and effector function development in the immune system. J Immunol. 2011;187:2841–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo SJ, et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szabo SJ, et al. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haring JS, Badovinac VP, Olson MR, Varga SM, Harty JT. In vivo generation of pathogen-specific Th1 cells in the absence of the IFN-gamma receptor. J Immunol. 2005;175:3117–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naiche LA, Harrelson Z, Kelly RG, Papaioannou VE. T-box genes in vertebrate development. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:219–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.105925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanov II, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston RJ, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurieva RI, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu D, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:674–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhry A, et al. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung Y, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17:983–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegazy AN, et al. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3(+)T-bet(+) cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity. 2010;32:116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang ES, Szabo SJ, Schwartzberg PL, Glimcher LH. T helper cell fate specified by kinase-mediated interaction of T-bet with GATA-3. Science. 2005;307:430–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1103336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch MA, et al. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linterman MA, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. 2011;17:975–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oestreich KJ, Huang AC, Weinmann AS. The lineage-defining factors T-bet and Bcl-6 collaborate to regulate Th1 gene expression patterns. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1001–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oestreich KJ, Mohn SE, Weinmann AS. Molecular mechanisms that control the expression and activity of Bcl-6 in TH1 cells to regulate flexibility with a TFH-like gene profile. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:405–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oldenhove G, et al. Decrease of Foxp3+ Treg cell number and acquisition of effector cell phenotype during lethal infection. Immunity. 2009;31:772–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osorio F, et al. DC activated via dectin-1 convert Treg into IL-17 producers. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3274–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Su MA, Wan YY. An essential role of the transcription factor GATA-3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2011;35:337–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1297–306. doi: 10.1038/ni.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou L, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghoreschi K, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pepper M, Pagan AJ, Igyarto BZ, Taylor JJ, Jenkins MK. Opposing signals from the Bcl6 transcription factor and the interleukin-2 receptor generate T helper 1 central and effector memory cells. Immunity. 2011;35:583–95. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakayamada S, Takahashi H, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Helper T cell diversity and plasticity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell DJ, Koch MA. Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:119–30. doi: 10.1038/nri2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudra D, et al. Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ni.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:639–46. doi: 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson NJ, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:950–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zielinski CE, et al. Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-gamma or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1beta. Nature. 2012;484:514–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Y, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic T(H)17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu KT, et al. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakayamada S, et al. Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity. 2011;35:919–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballesteros-Tato A, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:847–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:243–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oestreich KJ, Weinmann AS. T-bet employs diverse regulatory mechanisms to repress transcription. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Afkarian M, et al. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:549–57. doi: 10.1038/ni794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carter LL, Murphy KM. Lineage-specific requirement for signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)4 in interferon gamma production from CD4(+) versus CD8(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1355–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaplan MH, Sun YL, Hoey T, Grusby MJ. Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:174–7. doi: 10.1038/382174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lighvani AA, et al. T-bet is rapidly induced by interferon-gamma in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15137–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261570598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishikomori R, et al. Activated STAT4 has an essential role in Th1 differentiation and proliferation that is independent of its role in the maintenance of IL-12R beta 2 chain expression and signaling. J Immunol. 2002;169:4388–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Shea JJ, Lahesmaa R, Vahedi G, Laurence A, Kanno Y. Genomic views of STAT function in CD4+ T helper cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:239–50. doi: 10.1038/nri2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thierfelder WE, et al. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382:171–4. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Usui T, Nishikomori R, Kitani A, Strober W. GATA-3 suppresses Th1 development by downregulation of Stat4 and not through effects on IL-12Rbeta2 chain or T-bet. Immunity. 2003;18:415–28. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aronica MA, et al. Preferential role for NF-kappa B/Rel signaling in the type 1 but not type 2 T cell-dependent immune response in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;163:5116–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Avni O, et al. T(H) cell differentiation is accompanied by dynamic changes in histone acetylation of cytokine genes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:643–51. doi: 10.1038/ni808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grenningloh R, Kang BY, Ho IC. Ets-1, a functional cofactor of T-bet, is essential for Th1 inflammatory responses. J Exp Med. 2005;201:615–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiani A, et al. Regulation of interferon-gamma gene expression by nuclear factor of activated T cells. Blood. 2001;98:1480–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyazaki M, et al. The opposing roles of the transcription factor E2A and its antagonist Id3 that orchestrate and enforce the naive fate of T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:992–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bettini ML, et al. Loss of epigenetic modification driven by the foxp3 transcription factor leads to regulatory T cell insufficiency. Immunity. 2012;36:717–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Darce J, et al. An N-terminal mutation of the foxp3 transcription factor alleviates arthritis but exacerbates diabetes. Immunity. 2012;36:731–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]