Abstract

Nociceptive and neuropathic pain (NP) are common consequences following spinal cord injury (SCI), with large impact on sleep, mood, work, and quality of life. NP affects 40% to 50% of individuals with SCI and is sometimes considered the major problem following SCI. Current treatment recommendations for SCI-NP primarily focus on pharmacological strategies suggesting the use of anticonvulsant and antidepressant drugs, followed by tramadol and opioid medications. Unfortunately, these are only partly successful in relieving pain. Qualitative studies report that individuals with SCI-related long-lasting pain seek alternatives to medication due to the limited efficacy, unwanted side effects, and perceived risk of dependency. They spend time and money searching for additional treatments. Many have learned coping strategies on their own, including various forms of warmth, relaxation, massage, stretching, distraction, and physical activity. Studies indicate that many individuals with SCI are dissatisfied with their pain management and with the information given to them about their pain, and they want to know more about causes and strategies to manage pain. They express a desire to improve communication with their physicians and learn about reliable alternative sources for obtaining information about their pain and pain management. The discrepancy between treatment algorithms and patient expectations is significant. Clinicians will benefit from hearing the patient´s voice.

Keywords: neuropathic pain, nonpharmacological treatment, self-management, spinal cord injury

Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury Neuropathic Pain

Both nociceptive and neuropathic pain (NP) are common consequences following spinal cord injury (SCI). Pain significantly affects sleep, work, and quality of life and is associated with depression and anxiety. Approximately 40% to 50% of persons with an SCI develop NP,1 and it has been reported to be the major problem following SCI.2

A review by Siddall and Middleton published in 20063 commenced with the following statement: “The effective treatment of pain following spinal cord injury (SCI) is notoriously difficult.” Five years later, this is still relevant. Treatment recommendations for SCI-NP3,4 include the use of anticonvulsant or/and antidepressant drugs followed by tramadol/opioids. Trials of medications for SCI-NP often report limited efficacy, and even drugs shown to be effective in these studies have numerous drop-outs and report many adverse events.

Studies of nonpharmacological treatments have increased during the past few years. Treatment with acupuncture,5,6 transcranial direct current stimulation alone7 or in combination with visual illusion,8 visual illusion alone,8,9 and hypnosis10 reportedly have positive effects on SCI-NP. Few drop-outs and few side effects are reported in these trials. However, many of these nonpharmacological treatment options are not available in clinical practice today.

Cognitive and behavioral strategies have been assessed in a few studies and have reported improvements primarily in pain-associated variables.11-13

The aim of the conducted symposium was to highlight the patients’ perspectives on SCI-NP and to explore the impact of neuropathic pain, use of complementary treatments, coping strategies, and beliefs and expectations from the patient’s perspective and to reflect on and discuss the gap between treatment recommendations and patient expectations.

Are Drugs the Solution?

As mentioned, current treatment recommendations for SCI-NP focus mainly on pharmacological treatments.3 In a proposed treatment algorithm a few years ago, nonpharmacological treatments were only mentioned briefly.3 Heutink et al,14 however, reported in a 2011 survey a superior effect of nonpharmacological strategies compared to pharmacological. Fifty-five to 83% of the patients rated treatments such as acupuncture/magnetizing, physiotherapy/exercise, massage/relaxation, and psychological treatments as largely effective.15 Opioids and benzodiazepines were considered the most effective drugs, by 55% and 53%, respectively.

Opioid medication is listed for treating SCI-NP in treatment recommendations after the use of antidepressant and anticonvulsant drugs.4 Even so, opioids are reportedly more common than antidepressants and anticonvulsants15-18 and are considered by patients to be more effective.14,15,19 Drugs in general are described as having limited effect,20,21 with many unwanted side effects20,21; individuals also report having developed tolerance.20,21 Effects on cognitive abilities and constipation have been reported as main side effects limiting compliance.20

Four surveys have investigated the use of treatments commonly used for SCI pain.14,16,19,22 Several of these surveys report that non-pharmacological treatments are common,14,19,22 especially massage14,19 and acupuncture.22 Note, however, that these studies investigated SCI-related pain, not only neuropathic pain.

Nonpharmacological treatments were reported as most common and as most effective in 3 of the aforementioned 4 studies. Physical therapy was reported as the most effective treatment by Widerström-Noga et al23: 90% of their patients rated themselves improved.13 In a study by Warms et al,16 physical therapy was the second most effective treatment following opioid medication. Treatment with massage was considered to be the most helpful pain-relieving therapy by respondents in the other 2 surveys (Table 1),14,22 where massage was rated effective by approximately 90% of those who had tried it. Different forms of warmth were scored as very effective by the respondents in 2 of the studies,15,22 but warmth was not assessed as a separate treatment modality in the remaining 2 studies. It may be assumed perhaps that warmth was included in “physiotherapy.”14,16 Not only were massage and acupuncture reported to be superior to most medications for relief, but the effect was also rated as of longer duration in one of these studies.15

Table 1.

Patients’ rating of treatment effectiveness

| Treatment | n | Effective to a large extent | Not at all effective |

| Acupuncture/magnetising | 6 | 83% | - |

| Massage/relaxation | 75 | 59% | 3% |

| Physiotherapy and exercise | 16 | 69% | 6% |

| Psychological treatment | 11 | 54% | 11% |

| Opioids | 11 | 54% | 9% |

| Anticonvulsants | 32 | 47% | 6% |

Adapted from Heutink et al. Chronic spinal cord injury pain: pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and treatment effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:433-440.

Studies of treatment efficacy from controlled trials are sparse24 but increasing.25 Fattal et al24 in their review of the efficacy of physical therapeutics for treating SCI-NP identified 3 techniques: magnetic or electrical transcranial stimulation, trancutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS), and acupuncture. One 2009 review25 discusses possible treatments for SCI-NP and recommends exercise, massage, acupuncture, and psychological interventions despite the lack of studies.

Qualitative studies report that individuals with SCI and pain develop self-taught strategies for coping with their pain. These include warmth (eg, swimming/hot tub/shower), massage, stretching, exercise, rest and relaxation, and distraction.20,21

We have identified a gap between treatment recommendations and treatments studied in trials and those actually used and preferred by individuals with SCI and pain. This gap needs to be closed to improve the situation for all those individuals with SCI-related pain. We advocate multidisciplinary management of neuropathic pain after SCI, where different treatments and strategies can be tried and adjusted to each individual’s need and the individual effect.

Meeting the Knowledge Gap: What the Consumer Is Saying

Preparation for community life after SCI rehabilitation includes education and self-advocacy for maintaining optimal health and well-being.26,27 Prevention, identification, and management of complications associated with the primary condition become part of everyday life. Self-directed care is an important aspect of health for people living with SCI. With respect to chronic pain, there are now evidence-based methods to better evaluate and manage this devastating complication (for reviews see refs. 15 and 19). Pain knowledge and self-management are key evidence-based management strategies.28 However, in contrast to persons living with chronic pain from other conditions like cancer,29,30 arthritis,31 or chronic musculoskeletal pain,32 little attention is paid to those living with chronic pain after SCI. Thus there is a gap between the research knowledge and current clinical management of chronic post-SCI pain.

The knowledge/care gap may reflect many barriers, including patient as well as clinician knowledge/beliefs and the health care system barriers.33 Our preliminary survey of clinicians working in a specialty SCI rehabilitation center found that, although scoring well on pain knowledge and beliefs questionnaires, most (87.5%) expressed a need to know more about pain management. Our pilot survey of people living in community with SCI-related pain showed that 20% felt that they needed more medication while 48% felt that they were taking too much medication. Only 40% of respondents reported that they took their medication as prescribed. The mean overall pain relief reported was 4.4 (±2.4) (scale 0 to 10) and the mean overall satisfaction with pain management was only 4.9 (±3.2) (scale 0 to 10). These results highlight the need for consumer-relevant information about pain to enable each individual to better manage pain and self-advocate for improved pain care.

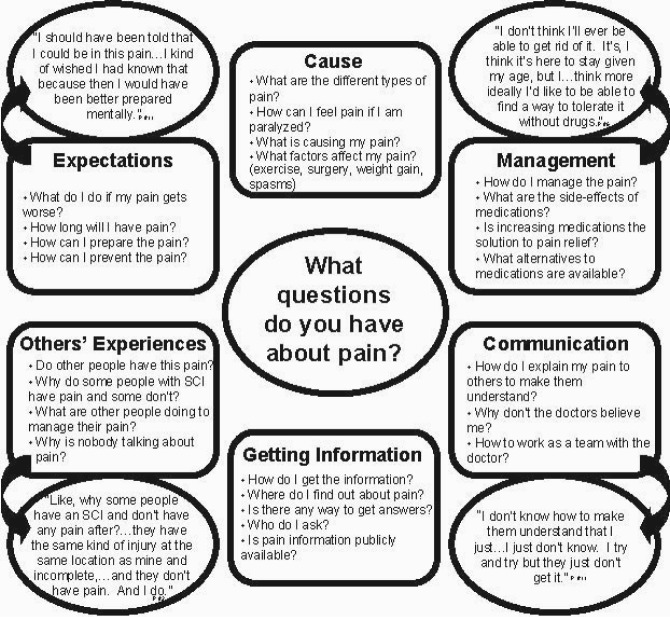

For education to be effective, it must be tailored to the information needs and preferences of the consumer.34,35 We used a qualitative approach to explore the questions that 12 community-dwelling individuals, with previous traumatic SCI, have regarding their chronic pain.36 In addition, we explored their preferred source, mode of delivery, and timing of information about SCI-related chronic pain. Qualitative content analysis was used to identify participants’ questions about their pain and to organize them according to theme. This revealed 6 emergent themes: (a) cause, (b) communication, (c) expectation, (d) getting information, (e) management, and (f) other’s experience with chronic pain. Many individuals were dissatisfied with the level of knowledge that family/ primary care physicians have about SCI-related chronic pain. Participants used a variety of sources to obtain information about chronic pain including health care providers, other SCI consumers, and the Internet. Participants preferred to have chronic pain information available to them on an as-needed basis rather than at a specific time during their rehabilitation. This study provided valuable information from the consumer’s perspective that can be used to develop relevant information so consumers can self-advocate and better manage SCI-related chronic pain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Questions regarding chronic pain were identified and classified into 6 main themes (square boxes). Illustrative quotes for each theme are depicted in circles. Reprinted, with permission, from Norman C, Bender JL, Macdonald J, Dunn M, Dunne S, Siu B, et al. Questions that individuals with spinal cord injury have regarding their chronic pain: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(2):114-124. With permission from Informa.

Moving Forward with Neuropathic Pain in Spinal Cord Injury

During rehabilitation following SCI, considerable attention is directed toward maximizing functional capacity, facilitating the learning of new knowledge and skills to maintain health, and supporting adjustment to the disability. The management of pain is subsumed among the many rehabilitation goals that need to be addressed. After discharge, individuals with SCI experience the stresses of living in the “real world.” Often, it is at this point that the problem of SCI-NP emerges or escalates.

Two qualitative studies were undertaken to better understand how individuals cope with SCI-NP.20,37 In the first study, we were interested in the impact of NP in community-living SCI persons in relation to physical, emotional, psychosocial, environmental, informational, practical, and spiritual domains and effective and ineffective pain coping strategies. The observation that some individuals seemed to have accepted the chronic pain and engaged in a full and meaningful life despite pain led to the second study, which focused on understanding the process of acceptance of pain.

Four themes emerged from the focus groups conducted for study 1. They included (1) the nature of pain, (2) coping, (3) medication failure, and (4) pain impact. These interrelated themes demonstrate the multidimensional impact of SCI-NP. It was apparent that all participants experienced significant physical pain that impacted their ability to live fully functioning and rewarding lives. These findings are consistent with the literature that reports that SCI-NP interferes with activities of daily living23,38 and daily function39 and negatively impacts work and social activity.40 In our participants, several physical factors contributed to increased pain, most commonly, fatigue and spasticity. The physical, emotional, and cognitive energies required on a daily basis to deal with the pain coupled with severe sleep disturbance resulted in increased pain and inability to cope with pain.

Analgesics and adjuvant medications were largely ineffective over the long term, and participants reported self-medicating with over-thecounter medications, alcohol, and marijuana. The cyclical pattern of trying medications that were mostly ineffective resulted in feelings of frustration and mounting levels of anxiety in relation to the inability to manage NP. Smeal and colleagues41 describe this phenomenon of patients becoming increasingly frustrated when they cannot find medications that control their pain without unwanted side effects.

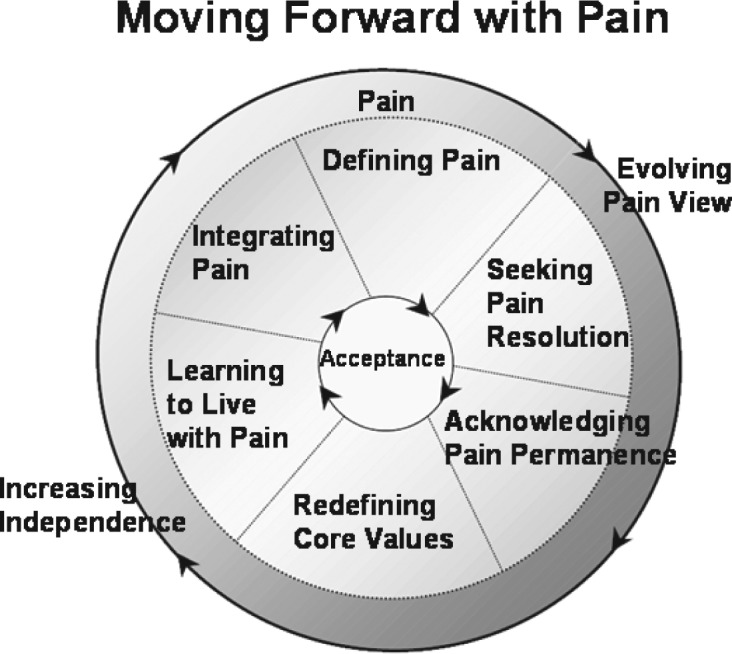

When efforts to alleviate pain have not been successful, individuals with SCI are often told that they will need to “learn to live” with the pain. Learning to live with the pain appears to be related to acceptance of pain, which facilitates adjustment.42 Participants who had accepted their pain were less likely to be taking pain medications and had active lives, despite the pain. For study 2, we recruited individuals who were no longer solely invested in seeking a cure for their SCI-NP. In-depth interviews were conducted with 5 men and 2 women who ranged in age from 30 to 67 years of age. The conceptual framework of the process of acceptance of NP in individuals with SCI is best described in terms of a wheel (see Figure 2). The 6 segments within this wheel represent each of the 6 phases. The individuals with SCI typically advanced through the 6 phases in a sequential fashion. They moved forward gradually through each phase as they gained experience in living with SCI-NP. Overlap between the respective phases occurred as the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural adjustments that were characteristic of each phase were adopted. The spokes of the wheel that separate each phase illustrate the periodic setbacks to a prior phase that can occur in response to an increase in pain severity. As the necessary adjustments were made over time, these SCI participants continued to move forward toward acceptance of NP. Two processes, “increasing independence” and “evolving pain view,” that are integral to moving forward through each phase are represented by the area between the 2 outer concentric circles.

Figure 2.

The process of moving forward with chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injured persons. Reprinted, with permission, from: Henwood P, Ellis JA, Logan J, Dubouloz C, D’Eon J. Acceptance of chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injured persons: A qualitative approach. Pain Manage Nurs. 2010. doi. org/10.1016/j.pmn.2010.05.005. Copyright © 2010 by Elsevier.

The findings from study 2 suggest that acceptance of pain was beneficial in terms of reducing suffering and facilitating a more satisfying and fulfilling life for these individuals. Relinquishing the expectation of a medical cure for NP and moving toward a self-management approach led to increased coping with pain for these participants.

Acknowledgments

The Norrbacka-Eugenia Foundation, Sweden; The Swedish Association for Survivors of Accident and Injury, Sweden; The Cancer and Traffic Injury Fund, Sweden, Neurotrauma Foundation, Canada; Canadian Paraplegic Association, Canada; and Penny Henwood RN, MScN.

References

- 1.Norrbrink Budh C, Lund I, Ertzgaard P, et al. Pain in a Swedish spinal cord injury population. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(6): 685-690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levi R, Hultling C, Nash MS, Seiger A.The Stockholm spinal cord injury study: 1. Medical problems in a regional SCI population. Paraplegia. 1995;33: 308-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddall PJ, Middleton JW.A proposed algorithm for the management of pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(2): 67-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baastrup C, Finnerup NB.Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(6): 455-475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nayak S, Shiflett S, Schoenberger N, et al. Is acupuncture effective in treating chronic pain after spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82: 1578-1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T.Acupuncture and massage therapy for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury - an exploratory study [published online ahead of print April 6, 2011]. Acupunct Med. 2011;29: 108-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Lima MC, et al. A sham-controlled, phase II trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of central pain in traumatic spinal cord injury. Pain. 2006;122(1-2):197-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler MD, Kumru H, Pelayo R, et al. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation and visual illusion on neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Brain. 2010;133(9): 2565-2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moseley GL.Using visual illusion to reduce at-level neuropathic pain in paraplegia. Pain. 2007;130(3): 294-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen MP, Barber J, Romano J, et al. Effects of self-hypnosis training and EMG biofeedback relaxation training on chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2009;57: 239-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehde D, Jensen M.Feasibility of a cognitive restructuring intervention for treatment of chronic pain in persons with disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2004;49: 254–258 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norrbrink Budh C, Kowalski J, Lundeberg T.A comprehensive pain management programme comprising educational, cognitive and behavioural interventions for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(3): 172–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton JW.Comparison of a pain management program with usual care in a pain management center for people with spinal cord injury-related chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(3): 206–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heutink M, Post MW, Wollaars MM, van Asbeck FW.Chronic spinal cord injury pain: pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and treatment effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(5): 433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardenas DD, Jensen MP.Treatments for chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a survey study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(2): 109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warms CA, Turner JA, Marshall HM, Cardenas DD.Treatments for chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: many are tried, few are helpful. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(3): 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnerup NB, Johannesen IL, Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Jensen TS.Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: a postal survey. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(5): 256–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norrbrink Budh C, Lundeberg T. Use of analgesic drugs in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(2): 87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widerstrom-Noga EG, Turk DC.Types and effectiveness of treatments used by people with chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: influence of pain and psychosocial characteristics. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(11): 600–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henwood P, Ellis JA.Chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: the patient’s perspective. Pain Res Manage. 2004;9(1): 39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löfgren M, Norrbrink C. “But I know what works” – Patients’ experience of spinal cord injury neuropathic pain rehabilitation. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Norrbrink Budh C, Lundeberg T.Non-pharmacological pain-relieving therapies in individuals with spinal cord injury: a patient perspective. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12(4): 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widerstrom-Noga EG, Felipe-Cuervo E, Yezierski RP.Chronic pain after spinal injury: interference with sleep and daily activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(11): 1571–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fattal C, Kong ASD, Gilbert C, Ventura M, Albert T.What is the efficacy of physical therapeutics for treating neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury patients? Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;52(2): 149–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardenas DD, Felix ER.Pain after spinal cord injury: a review of classification, treatment approaches, and treatment assessment. Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;1(12): 1077–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkell JA, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Jutai JW.Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(4): 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May L, Day R, Warren S.Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(7): 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGillion MH, Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, Lefort SM, Coyte P, Graham A.Randomized controlled trial of a psychoeducation program for the self-management of chronic cardiac pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(2): 126–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bender JL, Hohenadel J, Wong J, et al. What patients with cancer want to know about pain: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2): 177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Wit R, van Dam F, Loonstra S, et al. Improving the quality of pain treatment by a tailored pain education programme for cancer patients in chronic pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(3): 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stinson JN, Toomey PC, Stevens BJ, et al. Asking the experts: exploring the self-management needs of adolescents with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1): 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeFort SM.A test of Braden’s Self-Help Model in adults with chronic pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2000;32(2): 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolf A, Carr A, Frolich J, Guslandi M, Michel B, Zeidler H.Investigating the barriers to effective management of musculoskeletal pain: an international survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(12): 1535–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell SS.An overview of adult-learning processes. Urol Nurs. 2006;26(5): 349–352, 370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canadian Health Services Research Foundation Disseminating Research Tools to Help Organizations Create, Share and Use Research. 2011

- 36.Norman C, Bender JL, Macdonald J, et al. Questions that individuals with spinal cord injury have regarding their chronic pain: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(2): 114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henwood P, Ellis J, Logan J, Dubouloz C, D’Eon J.Acceptance of chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injured persons: a qualitative approach. Pain Manage Nurs. 2010. doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn. 2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen MP, Chodroff MJ, Dworkin RH.The impact of neuropathic pain on health-related quality of life: review and implications. Neurology. 2007;68(15): 1178–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanley MA, Masedo A, Jensen MP, Cardenas D, Turner JA.Pain interference in persons with spinal cord injury: classification of mild, moderate, and severe pain. J Pain. 2006;7(2): 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wollaars MM, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Brand N.Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(5): 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smeal WL, Yezierski RP, Wrigley PJ, Siddall PJ, Jensen MP, Ehde DM.Spinal cord injury. J Pain. 2006;7(12): 871–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCracken LM, Keogh E.Acceptance, mindfulness, and values-based action may counteract fear and avoidance of emotions in chronic pain: an analysis of anxiety sensitivity. J Pain. 2009;10(4): 408–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]