Abstract

Purpose:

To study the association of recurrent symptomatic urinary tract infections (UTIs) with the long-term use of clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) for the management of neurogenic bladder in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods:

Retrospective study of 61 SCI patients with neurogenic bladder managed by CIC. Subjects were selected from 210 SCI patients seen at the Yale Urology Medical Group between 2000 and 2010. Medical UTI prophylaxis (PRx) with oral antimicrobials or methenamine/ascorbic acid was used to identify patients with recurrent UTI. The number of positive cultures (≥103 cfu/mL) within a year prior to starting PRx was used to confirm the recurrence of UTI.

Results:

Fifty-one male and 10 female subjects were managed with CIC. Forty-one (67%) subjects were placed on medical PRx for symptomatic recurrent UTI. Seventeen (28%) subjects had at least 3 positive cultures within the year prior to starting PRx. Fifteen of 20 (75%) subjects not on PRx had no complaints of UTI symptoms in the final year of follow-up.

Conclusion:

Recurrent symptomatic UTIs remain a major complication of long-term CIC in SCI patients. Although CIC is believed to have the fewest number of complications, many SCI patients managed with long-term CIC are started on medical PRx early in the course of management. Future studies are needed to determine the efficacy of routine UTI PRx in these patients as well as determine what factors influence why many patients on CIC experience frequent infections and others do not.

Keywords: bladder management, clean intermittent catheterization, neurogenic bladder, spinal cord injury, symptomatic urinary tract infections, UTI prophylaxis

Spinal cord injury (SCI) can lead to alteration in the function of the lower urinary tract causing urologic complications that have historically been a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this patient population. Neurogenic voiding dysfunction is caused by the effect of SCI on the urethral sphincter and on the function of the detrusor muscle. Optimal bladder management should enable emptying of the bladder on a routine, frequent schedule, and allow patients to remain free from urine leakage while storing it at low pressures. The introduction of clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) by Lapides and colleagues in 19721 revolutionized the management of neurogenic bladder, and studies have favored it as the preferred method of bladder management, especially in patients with preserved hand function.2

Although no randomized controlled studies have been done to compare the various methods of neurogenic bladder management, CIC is widely believed to be associated with fewer complications compared with other methods3 and has become the standard of care in SCI patients.4 A commonly cited retrospective study reported a 20% annual incidence of urinary tract infection (UTI) in persons with SCI5; sepsis, frequently caused by UTI, is among the leading causes of mortality in SCI patients.6 Early reports claimed that CIC greatly reduced rates of UTI in SCI patients; however, it is now clear that the majority of persons undergoing intermittent catheterization develop frequently recurrent or continuous bacteriuria.7 Urethral catheterization is associated with an increased risk of symptomatic infections8; despite improvements in catheter material, UTI remains a common complication of CIC. In this study, we investigated a population of SCI patients for the association of recurrent symptomatic UTI and the use of CIC.

Material and Methods

Institutional characteristics and patient selection

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Yale University School of Medicine. Subjects were selected from patients followed by 1 physician at the Yale Urology Medical Group Clinic. All patient visits at the clinic are logged by the Patient Financial Services Department under corresponding diagnosis codes. Follow-up notes from clinic visits or phone calls are recorded in patient charts by the same physician after each encounter.

Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: neurogenic bladder dysfunction; stable traumatic SCI at least 1 year after injury; bladder management with CIC; minimum of 1 year follow-up by the same physician at the Yale Urology Clinic; seen between the 2000 and 2010. Exclusion criteria were other etiology for neurogenic bladder such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, spina bifida, or diabetes; other methods of bladder management, including other catheterization methods or Crede maneuver; or had undergone urinary diversion.

A list of 930 potential subjects was generated by a search of the Patient Financial Services Department records using diagnosis codes for “neurogenic bladder” or “Spinal Cord Injury.” The search was limited to patients seen by the same physician at the Yale Urology Medical Group between 2000 and 2010. Initial review of the clinical records eliminated 720 potential subjects who had neurogenic bladder from other etiologies but did not have traumatic SCI. Of the 210 SCI patients with neurogenic bladder, another 149 subjects were excluded either because they had neurogenic bladder managed by methods other than CIC or had undergone urinary diversion. Only 61 traumatic SCI subjects with neurogenic bladder managed by intermittent catheterization and followed for at least 1 year after SCI were included in this study (Table 1).

| Age, years | 43.4 ± 16.3 |

| Sex, n | |

| Male | 51 (84) |

| Female | 10 (16) |

| Injury level, n | |

| Cervical | 24 (39) |

| Thoracic | 24 (39) |

| Lumbar | 12 (20) |

| Sacral | 1 (2) |

| Independence, n | |

| Paraplegic | 35 (57) |

| Tetraplegic | 18 (30) |

| Independent | 8 (13) |

| Duration of catheterization, years | |

| Before initiating PRx | 2.7 ± 3.3 |

| Subjects not requiring PRx | 7.2 ± 3.8 |

| Duration of follow-up, years | 5.8 ± 4.1 |

| Use of UTI PRx | |

| Yes | 41 (67) |

| No | 20 (33) |

Note: Data presented as mean ± SD, unless noted otherwise; data in parentheses are percentages. PRx = prophylaxis; UTI = urinary tract infection.

Outcome model

Patients experiencing recurrent UTI were identified by their continued use of medical UTI prophylaxis (PRx) at the time of last clinical follow-up. Medical UTI PRx is defined as the use of either oral antibiotics or methenamine/ascorbic acid to decrease the frequency of UTIs. Subjects were started on PRx when they had ≥3 UTIs within a 1-year period. For subjects on UTI PRx, the recurrent and symptomatic nature of their infections was verified by the number of positive cultures occurring within a year prior to starting PRx. Subjects were not placed on PRx if they had not had at least 3 episodes of symptomatic UTI within a 1-year period. For each subject not placed on UTI PRx, the number of symptomatic UTIs occurring in the final year of follow-up was recorded based on the number of times the patient complained of UTI symptoms, including cloudy/ malodorous urine, increased incontinence, fever, chills, and bladder spasms. When available, the number of positive cultures was also recorded. All cultures were taken only after subjects complained of UTI symptoms, and they were considered positive when subjects had >103 colony forming units (cfu)/mL of 1 or more organisms.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done with SPSS statistics version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Data were represented as counts and percentages for categorical variables. Means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 210 SCI patients with neurogenic bladder, only 61 subjects (51 males and 10 females) met the study criteria. The mean age of the 61 subjects was 43.4 years (±16.3; range, 12-86 years). The mean age for male and female subjects was similar: 43.5 years (±16.5) and 43.2 years (±15.5), respectively. The mean duration of follow-up for all subjects was 5.8 years (±4.1; range, 1-16 years). Eighteen (30%) subjects were quadriplegic, 35 (57%) were paraplegic, and 8 (13%) subjects were fully independent, having neurogenic bladder with preserved upper and lower limb functions.

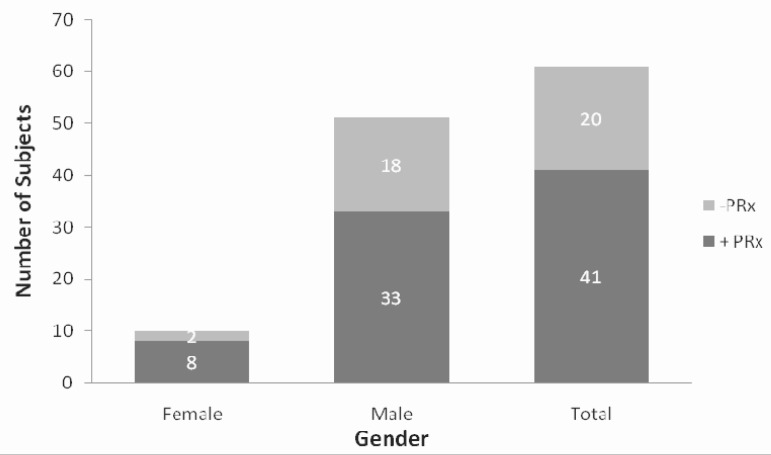

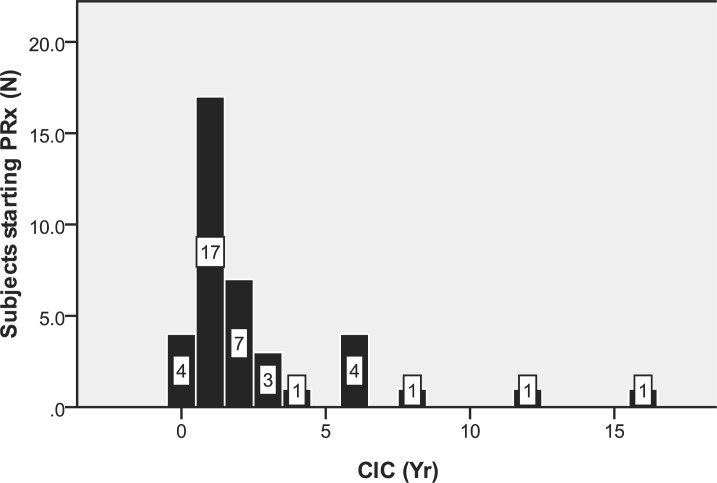

Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of males, females, and all subjects requiring PRx at the time of last follow-up. The date of initial PRx use was noted in 39 of 41 subjects; the results demonstrate that 28 (72%) were started on PRx within 2 years after initiation of CIC (Figure 2). The mean duration of follow-up for subjects on PRx as well as for those not using PRx are provided in Table 1. The date of initial catheter use was noted in 18 of the 20 (90%) subjects not requiring PRx.

Figure 1.

Bar graph illustrating number of subjects on urinary tract infection prophylaxis (PRx) based on gender. +PRx = subjects on PRx; -PRX = Subjects not using prophylaxis.

Figure 2.

Histogram of subjects started on urinary tract infection prophylaxis (PRx) based on years after initiation of clean intermittent catheterization (CIC).

Table 2 lists the number and percentage of subjects on UTI PRx with the number of positive cultures ≥103 cfu/mL available within the year prior to starting PRx. Culture results were not available for 11 (27%) of these subjects. Of the 20 subjects not placed on UTI PRx, 15 had no complaints of UTI symptoms in the final year of follow. The remaining 5 subjects were noted to have had only 1 complaint of symptomatic UTI. Three of these subjects had a positive culture ≥103 cfu/mL. Culture results were not available for the other 2 subjects.

Table 2.

Culture results for subjects on urinary tract infection prophylaxis

| Cultures ≥ 103 cfu | n (%) |

| ≥3 | 17 (41) |

| 2 | 7 (17) |

| 1 | 6 (15) |

Note: cfu = colony forming units.

Discussion

Neurogenic bladder is defined as the abnormal function of the urinary bladder secondary to any neurologic condition of the central nervous system or peripheral nerves involved in the control of micturition.9 Such conditions include SCI, neural tube defects, multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, and other diseases of peripheral nerves.10 To minimize the variability in study subjects, only cases of neurogenic bladder caused by traumatic SCI were included. The characteristics of our study subjects are consistent with the reported data for the SCI population in the United States. Eighty-one percent are male with a mean age of 40 years at the time of injury.11 It is estimated that about 12,000 new cases of SCI occur in the United States each year, with an estimated prevalence 262,000 persons in the year 2009. 11

Bladder management is an essential element in improved outcomes following SCI. The goal is to prevent upper and lower tract complications by maintaining adequate bladder drainage with low-pressure urine storage and voiding. UTI is the most common urological complication in SCI patients.12 Persons with SCI are at increased risk of UTIs due to bladder overdistention, outlet obstruction, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, increased intravesical pressure, vesicoureteral reflux, and large postvoid residuals. 8

CIC is a common bladder catheterization method used in the years following SCI.6 Some studies looking at the effectiveness of CIC have observed an increased frequency of UTIs, raising the need for prophylactic antibiotics.13 Oral antibiotics, methenamine compounds, and bladder instillations of providone iodine and chlorhexidine preparations are often used and have been shown to postpone bacteriuria for short periods in patients managed with CIC.14,15 Daily use of low-dose systemic antimicrobials such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has also been shown to be effective in reducing bacteriuria and symptomatic UTI in persons with acute SCI.7 The routine use of methenamine products or systemic antimicrobials for prophylaxis in long-term intermittent catheterization is controversial and not recommended16; however, in carefully selected subjects with frequent recurrent symptomatic UTIs, this may help improve quality of life.

This study retrospectively investigated the recurrence of symptomatic UTI in SCI patients managed with long-term CIC. The use of medical UTI PRx was used to identify subjects experiencing recurrent UTI. Patients were placed on UTI PRx only after they complained of 3 or more episodes of symptomatic UTIs within a 1-year period. Where available, urine culture results were used to confirm the need of PRx in those subjects using PRx.

In normal patients, UTIs are typically associated with fevers, chills, irritative voiding symptoms, or flank pain. These signs and symptoms are often poorly sensitive or specific in SCI patients,17 and the presence of UTI may be manifested by 1 or more of the following: vague back or belly discomfort, leakage between catheterizations, increased spasticity, cloudy urine with increased odor, autonomic dysreflexia, fevers, decreased appetite, or lethargy.18 All subjects in this study had been followed by the same physician, and the symptomatic and recurrent nature of their infections was consistently and reliably recorded before the initiation of medical PRx with either oral antimicrobials or methenamine/vitamin C.

The diagnosis of UTI is usually based on the quantification of uropathogens in voided urine, with significant bacteriuria defined as the amount of uropathogens in urine. This distinguishes true infection or colonization of the urinary tract from contamination.19 The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) defines UTI by the presence of significant bacteriuria with tissue invasion and resultant tissue response with signs and/or symptoms of UTI.20 The criteria for significant bacteriuria in SCI patients are dependent on the method of bladder management being used. To be diagnosed with catheter-associated UTI, patients managed with intermittent catheterization require ≥103 cfu/mL in addition to UTI symptoms unattributable to other sources.17 This cutoff for positive cultures was used to confirm the need for PRx in the subjects included in this study. Urine culture results were found for 31 of 41 (76%) subjects placed on UTI PRx. Culture results were not available for those subjects who were started on UTI PRx at initial follow-up after referral to our institution for management of frequent recurrent infections. In addition, culture results were not available for other subjects, because patients are often treated outside the purview of our office with cultures done by their primary care providers. Of all subjects included in the study, 17 had at least 3 positive cultures within the year prior to starting UTI PRx, confirming that at least 28% of our SCI patients were experiencing recurrent symptomatic UTI. These results suggest that symptomatic UTI remains a frequent, recurrent complication of CIC.

Due to the small number of females included in our study, we could not determine whether the difference in the percentage of male and female subjects requiring UTI PRx was statistically significant. The issue of sex as an independent risk factor for UTI in SCI patients has not been fully resolved. It is well known however that females have a higher incidence of UTI compared to males in otherwise healthy individuals with normal bladder function. Because females represent a minority of those with SCI, only a few studies have compared complication outcomes in male and female SCI patients. Waites and colleagues did not find sex to be an independent risk factor for UTI in a prospective study of 61 SCI patients.21 However, a comparative study by Bennett and associates demonstrated a higher incidence of UTI in females, especially with bowel organisms.22 Another study of 302 SCI patients on CIC found a significantly higher rate of clinical UTI in women, even though men and women had equal rates of bacteriuria. 23

Most of our patients on UTI PRx required it within 2 years of initiating bladder management with CIC. However, the 20 patients not placed on UTI PRx had been followed for a mean of 7 years without the need for PRx. This suggests that patients who will be placed on PRx are started on it early in the course of management, whereas those not needing PRx could go on without PRx almost indefinitely. Future studies will be needed to address what factors influence why certain patients do not experience frequent recurrent UTI while undergoing long-term bladder management with CIC.

The finding that 67% of our SCI patients are placed on PRx within 2 years of starting CIC is high and may not be generalizable to the average SCI population. Patients are often referred to our institution for management, because they have been experiencing frequent symptomatic infections. Previous studies reported that 80% to 90% of persons with acute SCI have bacteriuria within 2 to 3 weeks of starting intermittent catheterization.7 Esclarin and colleagues found an incidence of 2.75 episodes of bacteriuria/100 person-days, with 0.41 episodes/100 person-days incidence for UTI in a retrospective study of adults with acute SCI.24 Unlike previous reports, our study investigates the association of symptomatic UTI with long-term CIC in stable rather than acute SCI. Our results demonstrate that recurrent UTI remains a major complication of long-term bladder management with CIC.

Conclusions

Although intermittent catheterization is widely viewed as the healthiest bladder management option, many patients managed with long-term CIC will frequently experience recurrent symptomatic UTI. Our results highlight the continued need for improvements in bladder management methods to reduce rates of symptomatic infections in these patients. Future studies are needed to determine the benefit of UTI prophylaxis in these patients and to address what factors influence why certain patients managed with long-term CIC continue to experience frequent symptomatic infections when others do not.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was completed with support from the Yale Medical Student Research Fellowship Award/James G. Hirsch Endowed Medical Student Research Award.

Disclaimer: There are no conflicts of interests to disclose concerning this work.

References

- 1.Lapides J, Diokno AC, Silber SM, et al. Clean intermittent self-catheterization in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol. 1972;167 (4): 1584–1586, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill VB, Davies WE. A swing to intermittent clean self-catheterization as a preferred mode of management of the neurogenic bladder for the dexterous spinal cord patient. Paraplegia. 1988;26: 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weld KJ, Dmochowski RR. Effect of bladder management on urological complications in spinal cord injured patients. J Urol. 2000;163 (3): 768–772 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren JW. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;11: 609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Frankel HL, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and psychosocial outcomes of person spinal cord injured more than 20 years ago. Paraplegia. 1992;30: 617–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham. 2009. annual statistical report. February2010. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/public_content/pdf/2009%20NSCISC%20Annual%20Statistical%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf.AccessedFebruary1, 2011

- 7.Gribble MJ, Puterman ML. Prophylaxis of urinary tract infection in persons with recent spinal cord injury: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Am J Med. 1993;95: 141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenas DD, Hooton TM. Urinary tract infection in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76: 272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron AP. Pharmacologic therapy for the neurogenic bladder. Urol Clin N Am. 2010;37: 495–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler CJ, Dalton C, Panicker JN. Review of neurologic diseases for the urologist. Urol Clin N Am. 2010;37: 517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. February2010. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu.Accessed February2011. [PubMed]

- 12.Fonte N. Urological care of the spinal cord-injured patient. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35 (3): 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellstrom P, Tammela T, Lukkarinen O, et al. Efficacy and safety of clean intermittent catheterization in adults. Eur Urol. 1991;20: 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perman JW, Bailey M, Riley LP. Bladder instillations of trisdine compared with catheter introducer for reduction of bacteriuria during intermittent catheterisation of patients with acute spinal cord trauma. Br J Urol. 1991;67: 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kevorkian CG, Merritt JL, Ilstrup DM. Methenamine mandelate with acidification: an effective urinary antiseptic in patients with neurogenic bladder. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59: 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50: 625–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leoni ME, Esclarin De Ruz A. Management of urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9: 780–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29: 527–573 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooton TM. The epidemiology of urinary tract infections and the concept of significant bacteriuria. Infection. 1990;18 (suppl 2): S40–S43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Consensus Statement The prevention and management of urinary tract infections among people with spinal cord injuries. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1992;15: 194–2041500945 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waites KB, Canupp KC, DeVivo MJ. Epidemiology and risk factors for urinary tract infection following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74: 691–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett CJ, Young MN, Darrington H. Differences in urinary tract infections in male and female spinal cord injury patients on intermittent catheterization. Paraplegia. 1995;33: 69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siroky MB. Pathogenesis of bacteriuria and infection in the spinal cord injured patient. Am J Med. 2002;113 (1A):67S–79S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esclarin DR, Garcia LM, Herruzo CR. Epidemiology and risk factors for urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 2000;164: 1285–1289 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]