Abstract

How do humans respond to indirect social influence when making decisions? We analysed an experiment where subjects had to guess the answer to factual questions, having only aggregated information about the answers of others. While the response of humans to aggregated information is a widely observed phenomenon, it has not been investigated quantitatively, in a controlled setting. We found that the adjustment of individual guesses depends linearly on the distance to the mean of all guesses. This is a remarkable, and yet surprisingly simple regularity. It holds across all questions analysed, even though the correct answers differ by several orders of magnitude. Our finding supports the assumption that individual diversity does not affect the response to indirect social influence. We argue that the nature of the response crucially changes with the level of information aggregation. This insight contributes to the empirical foundation of models for collective decisions under social influence.

To what extent are the opinions we hold about subjective matters the result of our own considerations or a reflection of the opinions of others? Even though we would like to believe the former, in most real-life situations individual opinions are highly interdependent. They are, directly or indirectly, influenced by cultural norms, mass media and interactions in social networks. The combined effects of these influences is known as social influence – individuals acting in accordance to the beliefs and expectations of others1. Social influence can be categorised as direct or indirect. The former is the result of one individual directly affecting the opinion of another, typically through coercion or persuasion. The latter is a more subtle psychological process and takes place when one's opinion and behaviour is influenced by the availability of information about others' actions. Our main focus in this paper is on the second form, therefore we regard social influence as implicitly indirect.

Social influence can be readily observed in common collective decision processes, e.g. political polls2, panic stampedes3, stock markets4, cultural markets5, or aid campaigns6. Some of these collective decisions can trap a population in a suboptimal state, for example a financial bubble due to financial actors' herding behaviour7. Alternatively, they may steer a system into positive directions, such as increased tax compliance rates8. However, understanding how such collective decisions are formed, evaluating their benefit for the population, and even directing their outcomes, is conditional on quantifying how people perceive and respond to social influence.

Theoretical work in this field requires to specify a social structure together with mechanisms by which influence exerted by that social structure is internalised by the individuals9. Typically, it is considered that individuals form opinions in an interaction network (defined in terms of their social acquaintances) in which they are subject to complex inter-personal influences.

As early as 1956, French postulated a theory of social power, in which social structure is represented as an explicit interaction network10. An individual adopts an opinion that equals the mean of his own opinion and those he interacts with. Assuming that knowledge about the opinion of others is available, the theory predicts that well-connected populations invariably reach consensus.

Later, social psychologists and mathematicians have extended and built upon French's social power theory. Prominent works account for weighted averaging of others' opinions11, probability distribution of opinions12, and importance of positioning in the interaction network13. In particular, Latané made a notable quantitative contribution with his social impact theory14, which showed via empirical evidence that the fraction of individuals conforming to a group opinion is a power function of the group size (with exponent less than 1). Recent research has also shown how the identification of an individual with a group affects the final distribution of opinions15. In most models based on interaction networks, it is usually found that individuals respond in a highly non-linear manner, e.g. opinion fragmentation, due to the complexities involved in inter-personal influences16.

In this paper, we contribute to these theoretical investigations by analysing a decision-making experiment based on aggregate information instead of on explicit interaction networks. Our approach assumes that in some decision-making scenarios it is not always possible to have full information about others' opinions. Instead, only some sort of aggregated representation of all opinions is available, which arguably provides less information. For example, individual compliance to social norms has been shown to depend on knowing the average compliance rate in the population17. Other examples include book purchases being influenced by best-sellers lists that are typically compiled from average book store sales18, or recommender systems offering buyers products whose quality has been estimated as the average of all ratings19. We are, therefore, interested in evaluating whether individuals react differently when subjected to limited information compared to the non-linear response with full information.

Quantification of human responses to aggregated information is scarce. We present empirical evidence of how individuals react to it in a controlled environment. The empirical study we analyse was conducted by Lorenz et al.20. In this experiment individuals were asked to guess the correct answer to six quantitative questions with an objective answer (such as “What is the border length between Switzerland and Italy?”) repeatedly over five experimental rounds (see Table 1). Subjects were assigned to three different treatments in which they had (i) no information about others' guesses during all rounds, (ii) the mean of all guesses in the previous round or (iii) full information about others' estimates. Here, we focus on (ii), and report a statistically significant linear dependence between the change in one's estimate and the distance of the previous estimate from the mean.

Table 1. Experimental Setup. The experiment consisted of 12 sessions (S) each composed of 12 subjects. In each session, the 12 subjects had to answer two questions (Q) in the no information, two in the aggregate and two in the control condition (see main text), for a total of six questions. The order of the questions was randomised across sessions. After each of the five rounds subjects were asked the same question again and could revise their answers depending on the information available to them. In the table, columns indicate question number and rows – information regime. Each cell lists the sessions when a given question was asked for a particular information regime.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no info | S1,S4, S7,S10 | S2,S5, S8,S11 | S3,S6, S9,S12 | S1,S4, S7,S10 | S2,S5, S8,S11 | S3,S6, S9,S12 |

| agregate info | S3,S6, S9,S12 | S1,S4, S7,S10 | S2,S5, S8,S11 | S3,S6, S9,S12 | S1,S4, S7,S10 | S2,S5, S8,S11 |

| full info | S2,S5, S8,S11 | S3,S6, S9,S12 | S1,S4, S7,S10 | S2,S5, S8,S11 | S3,S6, S9,S12 | S1,S4, S7,S10 |

Results

We analyse the following set-up: a set of N subjects were asked six quantitative questions with a clearly defined objective truth. Individuals did not know a priori the true answers, and thus could only provide a guess. Each question was repeated for five consecutive rounds. At the end of each round, the subjects were presented with either some or no information about others' guesses, after which they could revise their own estimate. Let xi(t) be the guess of individual i

[1, N] at round t

[1, N] at round t

[1, 5] for a particular question. The arithmetic average of all N individuals at time t is then denoted as

[1, 5] for a particular question. The arithmetic average of all N individuals at time t is then denoted as  . In the aggregate regime subjects are presented with

. In the aggregate regime subjects are presented with  at the end of round t before making their next guess xi(t + 1). We study how the change in one's opinion, Δxi(t) = xi(t) − xi(t − 1), is related to its the distance from the mean in the previous time step

at the end of round t before making their next guess xi(t + 1). We study how the change in one's opinion, Δxi(t) = xi(t) − xi(t − 1), is related to its the distance from the mean in the previous time step  . From the experimental data, we can calculate Δxi(t) and

. From the experimental data, we can calculate Δxi(t) and  across all rounds, subjects, questions and sessions.

across all rounds, subjects, questions and sessions.

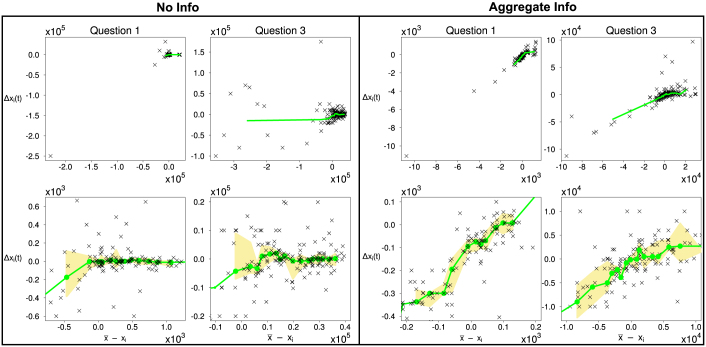

At the finest granularity of the data, there are N = 12 subjects answering a given question for a given information condition over five rounds. In total, one would have 12 × 4 = 48 data points. Considering, however, that each question was asked four times at a given information condition (see Table 1), we pool these responses together to produce 48 × 4 = 192 samples per information condition and per question. In Figure 1, we have plotted typical Δxi(t) vs.  for two questions. The left column shows that in the no information regime there is no particular dependency between the distance to the average and the ensuing adjustment of one's guess. In contrast, there is a positive linear relation in the aggregate information regime.

for two questions. The left column shows that in the no information regime there is no particular dependency between the distance to the average and the ensuing adjustment of one's guess. In contrast, there is a positive linear relation in the aggregate information regime.

Figure 1. Scatter plots for questions 1 (first and third column) and 3 (second and fourth column).

The green lines show median smoothing: the x-axis has been split into equally sized bins of size 10 (arbitrary), and the medians in each bin are plotted. The bottom row shows median smoothing with shaded areas corresponding to error bars between the first and third quartile of each bin. Note the scaling of the x- and y-axis.

We formalise this qualitative argument by the following linear regression model.

with the associated null hypothesis  , and two-sided alternative

, and two-sided alternative  .

.

Due to the experimental set-up, in particular the nature of the questions, subjects did not have a solid idea about the true answers. However, the questions were not too hard to prevent educated guesses about the approximate order of magnitude. Lorenz et al.20 note that the initial opinion distribution for each question is right-skewed – a majority of estimates are low and a minority fall on a fat right tail. Nevertheless, in Methods, we justify using Eq. 1 to model the aggregate information regime.

It is important to mention that, in principle, regression models, such as ours, cannot make explicit claims regarding cause and effect. Rather, the primary goal is to mathematically derive one variable from the other with as high fidelity as possible. We posit that in the empirical case considered here, one is able to infer the main causality direction, because the study was designed with the main purpose of evaluating how social influence affects one's decisions. Therefore, subjects were exposed to social information prior to their decision making. We, therefore, argue that in the aggregate regime, one of the main causes for an opinion change is knowledge of the mean (other causes being unobservable factors, such as conviction in own opinion, beliefs about others' expertise, etc.).

Table 4 shows all results of estimating the linear model. We focus primarily on the estimation of β1, as the constant term, β0, is heavily influenced by a few outliers, and thus exhibits large standard errors even when significant. From the reported p-values, we see that the impact of the distance to the mean opinion,  , is highly significant across all questions (with low rob. std. errors) in explaining one's own opinion change. Furthermore, the size of the effect shows that knowledge of the mean accounts for a considerable part of the opinion change.

, is highly significant across all questions (with low rob. std. errors) in explaining one's own opinion change. Furthermore, the size of the effect shows that knowledge of the mean accounts for a considerable part of the opinion change.

Table 4. Robust linear regression of Eq. 1. Uncorrected standard errors are reported for comparison only. Last column shows degrees of freedom.

| Estimate | Std. Errors | Robust std. errors | t-value | p-value | samples | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | β0 | −176.46 | 14.98 | 15.55 | −11.35 | < 2.2 × 10−16 | 192 | 190 |

| β1 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 9.57 | < 2.2 × 10−16 | |||

| Q2 | β0 | 35.33 | 12.6 | 12.9 | 2.74 | 0.007 | 192 | 190 |

| β1 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 2.89 | 0.004 | |||

| Q3 | β0 | −1321.5 | 828.2 | 853 | −1.55 | 0.12 | 192 | 190 |

| β1 | 0.83 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 6.25 | 2.7 × 10−9 | |||

| Q4 | β0 | −146.3 | 23.2 | 23.7 | −6.2 | 3.8 × 10−9 | 192 | 190 |

| β1 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 18.8 | < 2.2 × 10−16 | |||

| Q5 | β0 | 6.8 | 14.8 | 15.1 | 0.5 | 0.66 | 188 | 186 |

| β1 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 3.72 | 0.0003 | |||

| Q6 | β0 | −821 | 103 | 1387 | −0.6 | 0.55 | 188 | 186 |

| β1 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 15.3 | < 2 × 10−16 |

Discussion

Our main goal in this paper was to quantify how people respond to social influence when making decisions. In particular, we focused on a limited-information scenario, in which individuals possessed the mean of all opinions. This form of indirect social influence is prevalent in a wide range of collective decisions, e.g. norm compliance, product recommendations and purchases. Quantifying individual human behaviour in such contexts contributes to understanding such collective decisions.

We used a unique dataset from an experiment in which subjects had to guess the answer to quantitative questions repeatedly, while knowing the mean of all guesses. We studied how the change in individual guesses relates to their distance from the mean. Our analysis shows that a linear model is sufficient to explain this relationship for all experimental questions, with a significant and considerable impact. Furthermore, this finding holds for questions with correct answers that differ by about 10 orders of magnitude. Therefore, we emphasize that the result is not a first-order approximation of a non-linear regime around a narrow range of  .

.

Our quantitative insights represent a striking statistical regularity. Despite individual differences in subjects, e.g. emotions, conviction in one's own opinion, beliefs about the competency of others, and tendency to conform to the group opinion, the same mathematical relationship underlies the individual reactions to social influence. This suggests that once initial guesses are formed, diversity among subjects does not play a role in the adjustment of subsequent estimates. Moreover, we argue that the linear nature of the response is due to the level of information aggregation in the experiment. We believe that the availability of more fine-grained information, such as allowing group interactions or providing the opinion distribution, would recover the complex non-linear response found in most models of social influence.

Our finding also contributes to the design of agent-based models for collective decisions. Such models play an important role in testing individual-level interaction mechanisms that lead a population to favourable collective decisions. While most prominent models rely on ad-hoc assumptions about individual behaviour (e.g. linear voter model, Schelling's segregation model), with the increasing availability of experimental data, there is a growing interest in basing these assumptions on empirical regularities. The rule we revealed can, therefore, be used to further model, quantify and design collective decisions under aggregated information.

Methods

The model is estimated by the method of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), which is based to the following assumptions: (a)  (linear model is correct), (b)

(linear model is correct), (b)  (normality of the error distribution), (c)

(normality of the error distribution), (c)  (homoscedasticity), and (d)

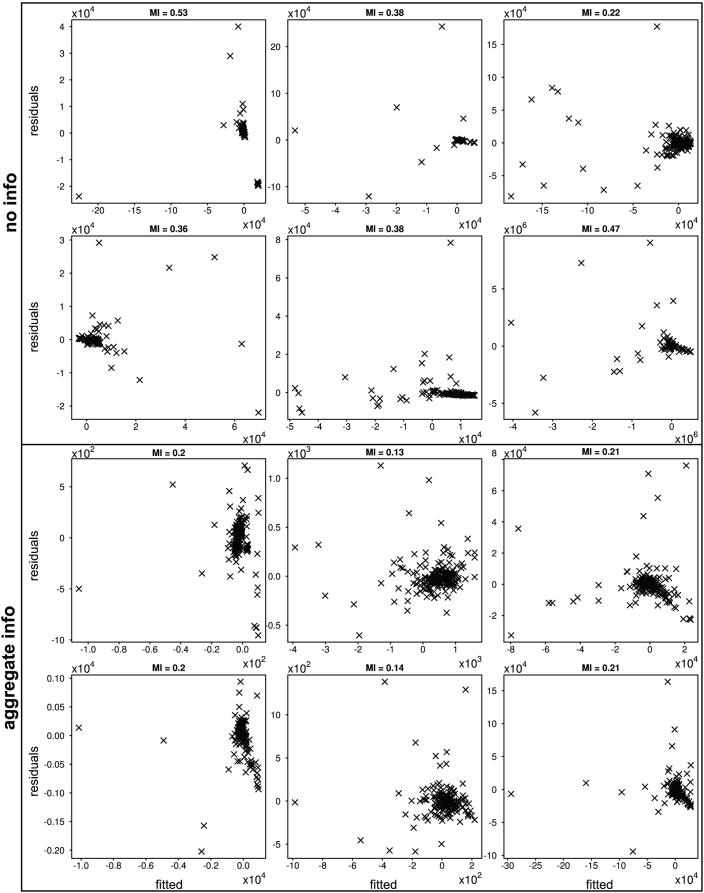

(homoscedasticity), and (d)  (independence of errors). First, to assess the overall feasibility of the linear model, we plot the residuals from the OLS estimation of Eq. 1 versus the fitted values, commonly known as a Tukey-Anscombe plot (Figure 2). A strong trend in the plot is evidence that the linear model is not suitable, consequently (a) is violated.

(independence of errors). First, to assess the overall feasibility of the linear model, we plot the residuals from the OLS estimation of Eq. 1 versus the fitted values, commonly known as a Tukey-Anscombe plot (Figure 2). A strong trend in the plot is evidence that the linear model is not suitable, consequently (a) is violated.

Figure 2. Residuals vs. fitted values for both information conditions and all questions.

The first two rows show the no-information condition, while the last two – the aggregate information condition. Questions are numbered from left to right and top to bottom. The mutual information (MI) is shown on top of each plot (see Methods for definition of MI).

For the no-information case, arguably, it is not reasonable to expect Eq. 1 to be valid as subjects did not have access to any information. Thus, any causal relation between Δxi(t) and  can be ruled out a priori.

can be ruled out a priori.

As seen in Figure 2, the residuals in the no information regime do not fluctuate randomly around the fitted values – a strong evidence against assumption (a). On the other hand, comparing with the aggregate information case, the Tukey-Anscombe plots do not exhibit a visible dependence between residuals and model fit, thus support assumption (a).

To actually quantify the presence of a trend in Figure 2, we compute the mutual information (MI) between the fitted values and their residuals. The concept of mutual information originates in information theory, and, intuitively speaking, measures the amount of information that two variables share, i.e. how much knowing one of these variables reduces uncertainty about the other21. Formally, the mutual information, I(X, Y), between variables X and Y, equals H(X) + H(Y) – H(X, Y), where H(X) is the information (entropy) in X, and H(X, Y) is the joint entropy of X and Y. If X and Y are independent then H(X, Y) = H(X) + H(Y), and thus the mutual information, I(X, Y), equals 0. We also make use of the inequality I(X, Y) ≤ min{H(X), H(Y)} to derive the normalisation Inorm(X, Y) = I(X, Y)/min{H(X), H(Y)}. In this way our MI estimate has an upper bound of 1, which is attained only if X and Y are identical.

The advantage of computing MI is that it is not only sensitive to linear correlations, but also to non-linearities that are not captured in the covariance22. The MI estimations for all questions are shown above each plot in Figure 2. Unsurprisingly, there is stronger dependency between residuals and fitted values in the no-information regime, especially where a trend is clearly visible. In contrast, all questions in the aggregate regime show very low values of MI.

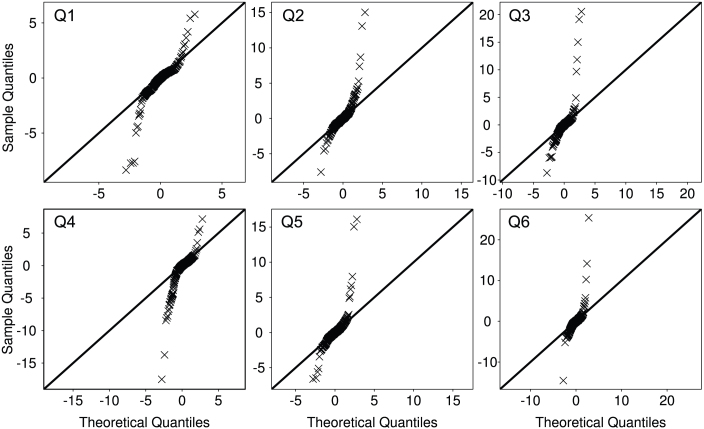

Second, in Figure 3 we check normality of errors by plotting the quantiles of the residual distribution against the quantiles of a normal distribution. The off-diagonal points in all questions clearly indicate the presence of a few large outliers, as expected for skewed data. Nonnormality of residuals plays no role for the BLUE (best linear unbiased estimator) properties of OLS estimators, provided (a) and (c) hold (the homoscedasticity assumption is evaluated below). However, exact t and F statistics will be incorrect. Therefore, we make use of the relatively large sample size in all questions to justify the asymptotic normality property of the OLS estimators23. It can be shown that by employing the central limit theorem and conditional on (a) and (c), OLS produces estimators that are approximately normal24, hence t-test can be carried out in the same way.

Figure 3. QQ Plots.

Theoretical quantiles of a normal distribution versus sample quantiles for all six questions. There are outliers in the data resulting in non-normal residuals. Question numbers (Q) are indicated on the top left corner of each plot.

Next, we verify the homoscedasticity assumption, (c), of  . To this end, we run the Koenker studentised version of the Breusch-Pagan test25. This test regresses the squared residuals on the predictor in Eq. 1 and uses the more widely applied Lagrange Multiplier (LM) statistics instead of the F-statistics. Although more sophisticated procedures, e.g. White's test, would account for a non-linear relation between the residuals and the predictor, we find that the Breusch-Pagan test is sufficient to detect heteroscedasticity in the data. Table 2 shows that the null hypothesis of homoscedastic error can be rejected with high significance for Questions 1, 2, 4, and 5. The consequence for the OLS method is that the estimated variance of β1 will be biased, hence the statistics used to test hypotheses will be invalid. Furthermore, none of the OLS estimators will be asymptotically normal. Thus, to account for the presence of heteroscedasticity, we use robust standard errors.

. To this end, we run the Koenker studentised version of the Breusch-Pagan test25. This test regresses the squared residuals on the predictor in Eq. 1 and uses the more widely applied Lagrange Multiplier (LM) statistics instead of the F-statistics. Although more sophisticated procedures, e.g. White's test, would account for a non-linear relation between the residuals and the predictor, we find that the Breusch-Pagan test is sufficient to detect heteroscedasticity in the data. Table 2 shows that the null hypothesis of homoscedastic error can be rejected with high significance for Questions 1, 2, 4, and 5. The consequence for the OLS method is that the estimated variance of β1 will be biased, hence the statistics used to test hypotheses will be invalid. Furthermore, none of the OLS estimators will be asymptotically normal. Thus, to account for the presence of heteroscedasticity, we use robust standard errors.

Table 2. Breusch-Pagan test for heteroscedasticity. Each column corresponds to one of the six questions. Since the linear model has only one regressor the Koenker version of the test has one degree of freedom for all questions.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM statistic | 0.46 | 11.84 | 0.0037 | 4.607 | 7.5679 | 1.1711 |

| p-value | 0.5 | 0.0005 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.005 | 0.28 |

| samples | 192 | 192 | 192 | 192 | 188 | 188 |

Finally, the serial correlation in (d) is tested by assuming the following AR(1) process for the error term

with  being the residuals from estimating Eq. 1 and

being the residuals from estimating Eq. 1 and  . One-period lag is sufficient to model error correlation, given that subjects answered the same question over just 5 rounds. In addition, by excluding the first guess when no information was available, we have effectively 4 periods. The OLS estimation of Eq. 2 in Table 3 indicates that α1 either is not significantly different from 0 (Questions 3, 5 and 6) or has a small effect when significant (Questions 1 and 4). Consequently, inferences based on t-tests and F-tests can be carried out.

. One-period lag is sufficient to model error correlation, given that subjects answered the same question over just 5 rounds. In addition, by excluding the first guess when no information was available, we have effectively 4 periods. The OLS estimation of Eq. 2 in Table 3 indicates that α1 either is not significantly different from 0 (Questions 3, 5 and 6) or has a small effect when significant (Questions 1 and 4). Consequently, inferences based on t-tests and F-tests can be carried out.

Table 3. First-order serial correlation of residuals.

| Estimate | Robust std. errors | t-value | p-value | samples | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | α0 | −3.6 | 14.02 | −0.26 | 0.79 | 191 | 189 |

| α1 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 2.47 | 0.01 | |||

| Q2 | α0 | 0.46 | 12.61 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 191 | 189 |

| α1 | −0.19 | 0.1 | −2 | 0.05 | |||

| Q3 | α0 | 7.2 | 836 | 0.009 | 0.9 | 191 | 189 |

| α1 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.64 | |||

| Q4 | α0 | −1.88 | 22.36 | −0.08 | 0.93 | 191 | 189 |

| α1 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 2.14 | 0.03 | |||

| Q5 | α0 | −0.32 | 14.9 | −0.02 | 0.9 | 187 | 185 |

| α1 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.43 | 0.15 | |||

| Q6 | α0 | −3.6 | 1388 | −0.003 | 0.99 | 187 | 185 |

| α1 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.85 |

All data analysis was done with R (http://www.r-project.org/, version 2.15.0). Quantile plots of the residuals were generated with rqq (package lawstat,version 2.3). Breusch-Pagan heteroscedasticity test was implemented by bptest (package lmstat, version 0.9-29). Finally to estimate Eq. 1, we used the standard lm function with robust standard errors calculated by hccm (package car, version 2.0-12). Mutual information was computed with multiinformation (package infotheo, version 1.1.0).

Author Contributions

P.M. and C.T. designed the analysis. P.M. analysed the data. P.M., C.T. and F.S. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ingo Scholtes and Antonios Garas for their useful comments in the early version of this manuscript.

References

- Kahan D. M. Social influence, social meaning, and deterrence. Virginia Law Review 83, 349–395 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Mutz D. Impersonal influence: effects of representations of public opinion on political attitudes. Political Behavior 14, 89–122 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Helbing D., Farkas I. & Vicsek T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 407, 487–90 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer D. & Teoh S. H. Herd behaviour and cascading in capital markets: a review and synthesis. European Financial Management 9, 25–66 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Salganik M. J., Dodds P. S. & Watts D. J. Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science 311, 854–856 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer F. & Mach R. The epidemics of donations: logistic growth and power-laws. PLoS ONE 3, e1458 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prechter R. Unconscious herding behavior as the psychological basis of financial market trends and patterns. Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets 2, 120–125 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. Misperceptions of social norms about tax compliance: from theory to intervention. Journal of Economic Psychology 26, 862–883 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Castellano C., Fortunato S. & Loreto V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Reviews of Modern Physics 81, 591–646 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- French J. R. A formal theory of social power. Psychological Review 63, 181–194 (1956). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedkin N. A formal theory of social power. Journal of Mathematical Sociology 12, 103–126 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot M. H. Reaching a consensus. Journal of the American Statistical Association 69, 118–121 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Friedkin N. E. & Johnsen E. C. Social positions in influence networks. Social Networks 19, 209–222 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Latané B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist 36, 343–356 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Groeber P., Schweitzer F. & Press K. How groups can foster consensus: the case of local cultures. Aritifical Societies and Social Simulation 12, 1–22 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hegselmann R. & Krause U. Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence: models, analysis and simulation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 5, 1–24 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Groeber P. & Rauhut H. Does ignorance promote norm compliance?. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory 16, 1–28 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bikhchandani S., Hirshleifer D. & Welch I. Learning from the behavior of others: conformity, fads, and informational cascades. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 12, 151–170 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hu N., Zhang J. & Pavlou P. A. Overcoming the J-shaped distribution of product reviews. Commun. ACM 52, 144–147 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz J., Rauhut H., Schweitzer F. & Helbing D. How social influence can undermine the wisdom of crowd effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 9020–5 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover T. M. & Thomas J. A. Elements of Information Theory Ch.2 (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kraskov A., Stögbauer H. & Grassberger P. Estimating mutual information. Phys. Rev. E 69, 066138 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi B. H. Econometrics Ch. 5 (Springer, Berlin, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J. Introductory Econometrics Ch.5 (Cengage Learning, Mason, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Koenker R. A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. Journal of Econometrics 17, 107–112 (1981). [Google Scholar]