Abstract

Background

Wolbachia are maternally inherited endosymbiotic bacteria that manipulate the reproductive success of their insect hosts. Uninfected females that mate with Wolbachia infected males do not reproduce due to cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI). CI results in the increased frequency of Wolbachia-infected individuals in populations. Recently, two Wolbachia strains, the benign wMel and virulent wMelPop have been artificially transinfected into the primary vector of dengue virus, the mosquito Ae. aegypti where they have formed stable infections. These Wolbachia infections are being developed for a biological control strategy against dengue virus transmission. While the effects of Wolbachia on female Ae. aegypti have been examined the effects on males are less well characterised. Here we ascertain and compare the effects of the two strains on male fitness in resource-limited environments that may better approximate the natural environment.

Methods

A series of population mating trials were conducted to examine the effect of Wolbachia infection status (with strains wMel and wMelPop) and male larval nutrition on insemination frequency, remating rates, the fecundity of females, the hatch rates of eggs and the wing length and fertility of males.

Results

wMel and wMelPop infections reduce the fecundity of infected females and wMelPop reduces the viability of eggs. Low nutrition diets for males in the larval phase affects the fecundity of wMel-infected females. Neither strain of Wolbachia affected sperm quality or viability or the ability of males to successfully mate multiple females.

Conclusions

The benign strain of Wolbachia, wMel causes similar reductions in fecundity as the more virulent, wMelPop, and neither are too great that they should not still spread given the action of CI. The ability of Wolbachia-infected males to repeat mate as frequently as wildtype mosquitoes indicates that they will be very good agents of delivering CI in field release populations.

Keywords: Mosquito, Fecundity, Symbiont, Multiple mating, Larval nutrition Wolbachia

Background

Wolbachia are maternally inherited endosymbiotic bacteria that naturally infect over half of all insect species [1]. Two different Wolbachia strains, native to Drosophila melanogaster, have been artificially transinfected into the primary vector of dengue virus, the mosquito Aedes aegypti, where they have formed stable infections [2,3]. These artificially created lines are the cornerstone of a biological control program to limit dengue transmission to humans that has progressed from the bench [2] to field cages [3] to open field releases [4]. In Far North Queensland, Australia, the site of the first release, the ability for Wolbachia infections to spread and be maintained long-term in wild populations has been demonstrated [4]. In the next few years, the ability of Wolbachia infected mosquitoes to reduce disease transmission in human populations will be tested in countries where dengue is endemic including locations in Vietnam, Indonesia and Brazil. In preparation for these releases, mathematical models are being employed to predict how Wolbachia will spread in populations of the vector and its consequences for dengue epidemiology. Key components of these models include the effects of Wolbachia on host fitness that can vary between strains. Understanding these differences are critical to ensure the correct strain is chosen for release sites that will maximise both spread and disease control outcomes.

The two Wolbachia strains, wMel and wMelPop differ in their effects on hosts and how they may be utilised to limit disease transmission. Both strains induce Cytoplasmic Incompatibility (CI) [2,3]. This reproductive manipulation favours Wolbachia infected females over uninfected in wild populations hence Wolbachia infections tend to spread [5,6]. CI is what first raised interest in Wolbachia as a biocontrol agent – because it can effectively drive itself into populations [7]. Both wMel and wMelPop also possess a characteristic that was only recently discovered, the ability to limit the replication of dengue virus inside the mosquito [3,8,9]. While the midgut of the mosquito almost always becomes infected following a dengue-laden blood meal, few mosquitoes progress to the point of secreting dengue in the saliva which is required for human transmission to occur. Interestingly, this same ability to block pathogen infection has been demonstrated for other viruses [8,10,11], the filarial nematode, Brugia pahangi[12] and an avian model of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium gallinaceum[8]. The wMelPop strain alone causes significant life shortening. Mosquitoes infected with the wMelPop strain exhibit on average a lifespan that is half that of uninfected mosquitoes [2]. The strain was initially selected for transinfection because of the life shortening it caused in its native Drosophila melanogaster[13]. Dengue, like many other pathogens is not immediately transmissible following consumption of an infected blood meal by a mosquito. There is a delay while the virus migrates to the salivary glands (7–10 days). The result is that only older mosquitoes surviving past this age can transmit virus, making lifespan reduction an attractive means for reducing transmission at the population level [7].

In addition to these traits, Wolbachia has been shown to also affect host fecundity, fertility, locomotion, dispersal, immunity, foraging and mating behaviours in a range of insects [14-19]. The frequency and magnitude of these changes can be specific to both host species and Wolbachia strains, in some cases enhancing fitness in one host but reducing it in another [19-21]. Studies so far in Ae. aegypti have shown that wMelPop infections can reduce a females’ fecundity, egg viability and ability to blood feed [2,22-24]. The wMel strain is relatively benign causing only a 10% reduction in longevity [3]. Given Wolbachia’s maternal inheritance, the nature of standard fitness assays and the fact that only female mosquitoes transmit disease, it is perhaps not surprising that the majority of this work has been female focused. Males have a unique and key role to play in populations because they are the agents of CI, blocking the successful reproduction of uninfected females during mating. Offspring of infected females then by default form a greater proportion of the subsequent generation and Wolbachia spreads. So it is critical that Wolbachia infected males are sufficiently competitive relative to wild type males. While female Ae. aegypti most often only mate once (but see [25]), males are more likely to attempt to mate multiple times [26-28]. The ability of individual males to successfully mate multiple females could speed the efficacy of CI in populations.

A number of male-based effects of Wolbachia have been characterised in Drosophila simulans. Snook et al. showed that Wolbachia-infected males produced sperm cysts at a slower rate than uninfected males, which resulted in infected males producing approximately 40% fewer sperm cysts than uninfected males [29]. This effect became more extreme as the flies aged. In addition, non-virgin Wolbachia-infected D. simulans males sire fewer progeny due to production of less competitive sperm [17] leading to reduced egg viability [29]. These phenotypes could result in fewer females being fully inseminated and an increased proportion of females being partially inseminated by Wolbachia-infected males. In mosquitoes, male mating performance has recently been shown not to vary following artificial transinfection of Wolbachia, however, in this case the donor insect for the Wolbachia was a sister mosquito species [30]. In cases where Wolbachia has been transferred from a phylogenetically distant host species, however, more extreme effects might be expected in the novel host according to host:parasite theory [21,31,32].

Lastly, while standard measures of fitness are employed in the laboratory under ideal conditions it is often difficult to generalise their meaning to the field, where nutritional availability is likely to be lower. The nutrition of larvae is an important determinant of adult mosquito fitness. Mosquitoes that grow in low-nutrition larval environments develop more slowly and have smaller body sizes and teneral reserves as adults compared to those reared in high-nutrition environments. In most cases, mosquitoes that grow in low-nutrition larval environments have reduced performance compared to their larger counterparts, including: reduced dispersal, flight potential [33,34], blood-meal size, fecundity [35-38], male fertility [39], immunity [40-42], survival [33,43,44], host-seeking behaviours [43,45,46] and mating success [39,47-49]. Recently, Yeap et al. [50] showed that Wolbachia infection could interact with larval nutrition to modify larval development times and the wing size of Ae. aegypti males. However, it is unknown how this interaction might affect performance of infected mosquitoes in the field. An understanding of these interactions may be used to inform breeding practices of mosquitoes prior to field release as was the case for medflies being mass reared for sterile insect release [51]. In this program, lab-reared males exhibited poor competitiveness [52] but supplementing their diets with protein improved courting and copulation frequencies, increased insemination and fertilisation success and decreased the likelihood of females remating [51,53,54].

Here we investigate the effects of two strains of Wolbachia – wMel and wMelPop – on the ability of males to successfully mate and reproduce with Wolbachia infected and Wolbachia free females. Trials with unequal (1:5) male-to-female ratios were conducted to test the potential of males to successfully mate with multiple females and to test the influence of this behaviour on the fecundity of females and their egg viability. Remating trials were conducted to test whether males could replenish seminal supplies and successfully mate with subsequent females. Lastly, males were reared on low-nutrition larval diets to test for potential interactions between nutritional status and Wolbachia infection. Response variables measured included the following traits: wing length, quantity and quality of sperm and the ability of males to successfully mate and reproduce with females.

Methods

Mosquito strains

The Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes employed in the development assays were from PGYP1, an inbred line of Ae. aegypti infected with the wMelPop strain of Wolbachia in 2008. Uninfected matched controls were of PGYP1.tet, a line of PGYP1 mosquitoes previously cured of Wolbachia through treatment with tetracycline [2]. Subsequently, outcrossed versions of these Wolbachia infected lines, A.PGYP1.out (wMelPop infected) and MGYP2.out (wMel infected), were generated using a scheme of mating to wild-type males as developed by Yeap et al. [50]. Wing length, mating and reproduction experiments were conducted using the outcrossed lines. The wild-type (control) line consisted of Ae. aegypti reared from eggs collected from breeding sites in Cairns, Queensland, Australia (16°51′S, 145°45′E), in 2009–2011. Male remating experiments and male fertility assays tested mosquitoes from the A.PGYP1.out and wild-type lines of mosquitoes, as described above.

Mosquito rearing and nutrition

All mosquitoes were reared in a climate-controlled insectary at 26 ± 1°C, RH 60 ± 5% with 12h:12h light/dark cycle. Ae. aegypti eggs were submerged in distilled water in a flask and connected to a vacuum for 30 minutes to induce hatching. Larvae for development assays were reared in 500ml of distilled water at a density of 25 larvae per tray. The control larval diet consisted of 2mg of TetraMin Tropical Fish Tablets per larvae per day. Low-nutrition diets consisted of 0.25mg, 0.2mg or 1.5mg of TetraMin Tropical Fish Tablets per larvae per day. The low nutrition treatment (0.25 mg food per day per larva) was based on a previous study showing increases in developmental time under this feeding regime [50].

Larvae for forewing length, mating and reproduction experiments and male fertility assays were reared in 3L of distilled water at a density of 150 per tray. For high-nutrition rearing, larvae were fed 2mg of TetraMin Tropical Fish Tablets per larva per day. For low-nutrition rearing, larvae were fed 0.2mg of TetraMin Tropical Fish Tablets per larva per day. Due to the delayed development of larvae reared on low nutrition, eggs for low-nutrition larvae were hatched two days before eggs for high-nutrition larvae. To obtain virgin mosquitoes, pupae were sorted by sex, based on size and shape, and separated. Adults were maintained in 30x30x30cm cages at a density of 450 mosquitoes per cage, with access to 10% sucrose solution.

Development assays

The effect of Wolbachia infections and larval nutrition on the development time of Ae. aegypti larvae was assessed. Two replicate trays of PGYP1 and PGYP1.tet larvae were reared on each of four nutritional regimes (2mg, 0.25mg, 0.2mg and 0.15mg per larvae per day). Development time was estimated by counting the number of pupae, in each tray, for 30 consecutive days. Each day, all pupae were removed and remaining larvae fed an adjusted amount of food.

Wing length

Wing lengths of 10 males from each of the MGYP1.out, PGYP1.out and wild-type lines, reared on high or low-nutrition (0.2mg/larva/day) larval diets were measured. At five days of age the right wings were removed from the mosquitoes and measured from the axillary incision to the wing tip, under a dissecting microscope using an eyepiece micrometer.

Mating and reproduction experiments

The mating success of males was examined by investigating the effect of Wolbachia infection and male larval nutrition on the number of females successfully inseminated, the fecundity of females and the hatch rate of their eggs. Males were reared on a high (2mg/larva/day) or low-nutrition (0.2mg/larva/day) larval diet and adults were reared to five days of age. Females were reared on high-nutrition larval diets only and aged to five days old. To test the impact of the infection status of males, five lines (mating combinations) were separately tested: MGYP2.out females x MGYP2.out males (MOMO), MGYP2.out females x wild-type males (MOWT), A.PGYP1.out females x A.PGYP1.out male (POPO), A.PGYP1.out females x wild-type males (POWT) and wild-type males x wild-type females (WTWT). The incompatible cross between Wolbachia-infected males and uninfected females was not tested [2,3].

In each experiment, 10 five-day-old males and 50 five-day-old females were knocked down by chilling and transferred into a 645mm3 cage. Males and females cohabited for 24 hours before all mosquitoes were aspirated out of the cage. To facilitate the development of eggs, all females used in this experiment were offered a human forearm (APT) from which to blood feed the day before and during each experiment for 15 minutes. Females were transferred into individual 40ml tubes, containing water and filter paper, for oviposition. Females were allocated seven days in oviposition tubes before they were examined for the presence or absence of eggs. Females that laid fewer than 10 eggs were excluded from the results to avoid the possibility of autogenous egg batches [55]. All other eggs were counted to determine fecundity.

Hatch rates of eggs were determined by transferring paper and water from oviposition tubes into trays containing 250ml water and 30mg TetraMin Tropical Fish Tablets. Eggs were left for 48 hours to hatch before the larvae in each tray were counted. As some eggs may not have matured during the first hatch, egg papers were dried down and stored for three days before immersing a second time. The numbers of larvae from the first and second hatch were combined to determine the hatch rate of eggs.

In some egg batches all eggs failed to hatch. When this occurred, the females that laid the eggs were dissected to confirm the presence or absence of sperm in their spermathecae. Using fine forceps, spermathecae were removed from females under a dissecting microscope. To stain the sperm, spermathecae were placed into 4μl of 1:4 Propidium Iodide:H20 (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) solution and a cover slip placed on top of the slide, bursting the spermathecae. The presence or absence of sperm was determined using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with a live/dead filter (Chroma Technology Corp.). The number of females successfully inseminated was calculated by adding the number of females that laid viable eggs and the number of inseminated females that laid eggs that did not hatch.

Male remating experiments

Males from the previous mating and reproductive success experiments were exposed to a second cohort of females. Previous research suggested that male Ae. aegypti could replenish seminal stocks within three days after mating [56]. Wildtype and A.PGYP1.out males were maintained on 10% sucrose for four days after the first trials. Due to males dying during this renewal period, the remating experiments involved randomly selecting only five, of the possible 10, males from the first trials and transferring these mosquitoes into cages containing only 25 five-day-old females. For all males, the infection status of females in their remating experiment was the same as those in their first mating success experiment. The experimental procedure was as per the mating and reproductive success experiments above. Males and females again cohabited for 24 hours and females were offered blood meals. Females were then transferred to individual oviposition tubes and fecundity and hatch rates of eggs were recorded.

Male fertility assays

This assay examined the quantity and viability of sperm of 10 male mosquitoes from the A.PGYP1.out and wild-type lines reared on high (2mg/larva/day) and low-nutrition (0.2mg/larva/day) larval diets. Sperm were stained using an Invitrogen Live/Dead Sperm Viability Kit (L-7011) (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) using the following protocol. For each day of experiments, a 50-fold dilution of the SYBR 14 stock solution in HEPES buffer (10mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 10% BSA, pH 7.4) was prepared and a master dye-mix was then created by combining 1:1:3 SYBR 14 dilution, Propidium Iodide, and H20. The master dye-mix was stored on ice and in the dark for the duration of the day’s dissections. To each sperm dilution, 5μl of master dye-mix was added and mixed gently but thoroughly with a pipette.

Previous research has shown that sperm quantity can be reliably estimated in Ae. aegypti by counting multiple aliquots of a sperm sample (10 of 40) [39]. Estimates of sperm quantity were, therefore, determined by spotting 10 5μl aliquots of sperm dilution onto a multiwell slide. Slides were left to air dry at room temperature and in the dark. Upon examination, 5μl 1x PBS was added to each well of the slide and a cover slip carefully placed onto the slide. Samples were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with a live/dead filter (CHROMA Technology Corp.). The total count of the 10 aliquots was averaged and multiplied by 40 to estimate the total quantity of sperm of each male.

Sperm viability protocol was as per sperm quantity assays with the following exceptions. The viability of sperm was determined by spotting 10 2μl aliquots of sperm dilution onto a multiwell slide and incubating at room temperature in the dark for 10 minutes. A cover slip was then placed over the slide and each well immediately examined using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with a live/dead filter (Chroma Technology Corp.). The viability of sperm was calculated by dividing the total number of live sperm by the total (live + dead) number of sperm counted from each male.

Statistical analysis

All data were checked for normality by distribution model fitting and variances checked for equality. The wing length, number of females that laid eggs, fecundity and sperm quantity and viability were normally distributed and were analysed with general linear models, with significant factors examined using appropriate t-tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Larval development times, hatch rates of eggs and remating success of males data were not normally distributed and could not be transformed; therefore these data were analysed using generalized linear models and significant factors were examined using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction. All data analysis was conducted using SPSS (IBM).

Approval for blood feeding by human volunteers for maintenance of the mosquito colony was granted by The University of Queensland Medical Research Ethics Committee (#200700137).

Results

Larval development

Wolbachia infections did not affect the development of larvae. A generalized linear model (Poisson with log link error) showed that nutrition (Wald = 79.425, P < 0.001), but not mosquito line (Wald = 0.562, P = 0.454) and interactions between these factors (Wald = 0.759, P = 0.859), affected larval development. Compared to control nutrition, all low-nutrition regimes significantly increased the median larval development time (0.25mg: Z = −11.61, P <0.001; 0.2mg: Z = −12.093, P <0.001; 0.15mg: Z = −12.469, P < 0.001).

Wing length

There was a significant difference between the wing length of low and high-larval nutrition males (F = 409.439, P < 0.001), but there was no effect of Wolbachia infection (F = 0.537, P = 0.587) or interaction between the factors (F = 2.789, P = 0.070). Males reared on low nutrition had smaller wings ( = 3.873, SEM = 0.029) than males reared on high nutrition ( = 4.716, SEM = 0.030).

Number of females successfully inseminated

Male larval nutrition, but not Wolbachia infections, influences the number of females that lay eggs. The number of females successfully inseminated was affected by the larval nutrition of the male (F = 10.143, df = 1, P < 0.05). Fewer females were inseminated by males reared on low larval nutrition diets ( = 3.9, SEM = 0.26) than by males reared on high nutrition diets ( = 5, SEM = 0.24). Mosquito line (F = 2.48, df = 4, P = 0.065) and interactions between mosquito lines and male larval nutrition (F = 0.114, df = 4, P = 0.976) did not affect the number of females that laid eggs.

Fecundity

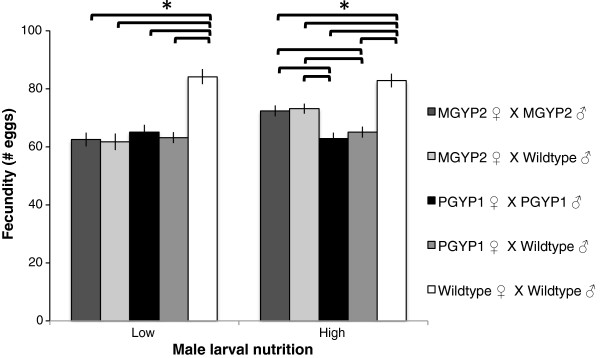

Larval nutrition of males (F = 7.551, df = 1, P < 0.001), Wolbachia infections in females (F = 26.908, df = 4, P < 0.001), and interactions between these factors (F = 3.745, df = 4, P < 0.05) affected fecundity. Wild-type females laid significantly more eggs than Wolbachia-infected females, regardless of male nutrition or infection status. When males were reared on high nutrition, wMel-infected females laid more eggs than wMelPop-infected females, irrespective of male infection status. However, when males were reared on low nutrition, no difference was observed between the fecundity of wMel and wMelPop-infected females (Figure 1, Table 1). wMel-infected females that mated with males reared on high-nutrition larval diets laid more eggs than those that mated with males reared on low-nutrition larval diets (Table 2).

Figure 1.

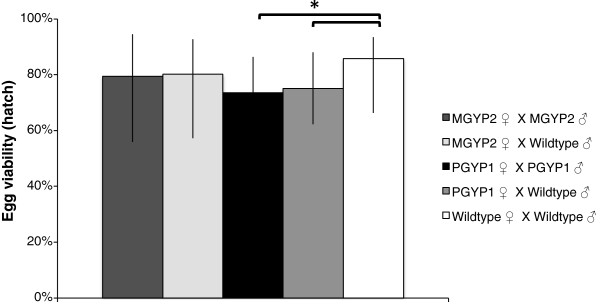

Egg viability expressed as median hatch rate ± quartiles. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is significant if *P < Holm-Bonferroni α (Table 3). The wMelPop strain in female Ae. aegypti (A.PGYP1.out) reduced the hatch rates of eggs.

Table 1.

Summary of statistics comparing the fecundity of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti

| Male larval nutrition | Line 1 | Line 2 | t | df | P | Holm-Bonferroni α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low |

POPO |

WTWT |

−5.208 |

149.789 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

| POWT |

WTWT |

−6.447 |

143.388 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

|

| MOWT |

WTWT |

−5.731 |

143.918 |

0.000 |

0.006 |

|

| MOMO |

WTWT |

−6.069 |

142.731 |

0.000 |

0.007 |

|

| MOWT |

POPO |

−0.876 |

142.470 |

0.382 |

0.008 |

|

| MOMO |

POPO |

−0.740 |

142.995 |

0.460 |

0.010 |

|

| POPO |

POWT |

0.610 |

146.934 |

0.543 |

0.012 |

|

| MOWT |

POWT |

−0.414 |

128.308 |

0.680 |

0.017 |

|

| MOMO |

POWT |

−0.212 |

140.967 |

0.833 |

0.025 |

|

| MOMO |

MOWT |

0.209 |

135.443 |

0.835 |

0.050 |

|

| High | POPO |

WTWT |

−6.434 |

197.020 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

| POWT |

WTWT |

−5.771 |

205.069 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

|

| MOWT |

POPO |

3.864 |

182.960 |

0.000 |

0.006 |

|

| MOMO |

WTWT |

−3.401 |

184.690 |

0.001 |

0.007 |

|

| MOMO |

POPO |

3.415 |

183.289 |

0.001 |

0.008 |

|

| MOWT |

WTWT |

−3.259 |

179.891 |

0.001 |

0.010 |

|

| MOWT |

POWT |

3.077 |

197.993 |

0.002 |

0.012 |

|

| MOMO |

POWT |

2.687 |

195.237 |

0.008 |

0.017 |

|

| MOMO |

MOWT |

−0.284 |

166.015 |

0.777 |

0.025 |

|

| POPO | POWT | −0.773 | 214.391 | 0.441 | 0.050 |

MGYP2.out females x MGYP2.out males (MOMO), MGYP2.out females x wild-type males (MOWT), A.PGYP1.out females x A.PGYP1.out male (POPO), A.PGYP1.out females x wild-type males (POWT) and wild-type males x wild-type females (WTWT). Unequal variance t-test is significant if P < Holm-Bonferroni α.

Table 2.

Summary of statistics comparing the fecundity of Wolbachia-infected or uninfected Ae. aegypti reared on high or low nutrition diets

|

Male larval nutrition |

t |

df |

P |

Holm-Bonferroni α |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| MOMO |

MOMO |

3.210 |

137.637 |

0.002 |

0.010 |

| MOWT |

MOWT |

−3.364 |

119.985 |

0.001 |

0.012 |

| POPO |

POPO |

0.691 |

151.755 |

0.491 |

0.017 |

| POWT |

POWT |

−0.681 |

209.703 |

0.496 |

0.025 |

| WTWT | WTWT | 0.364 | 167.047 | 0.716 | 0.050 |

Unequal variance t-test is significant if P < Holm-Bonferroni α.

Egg viability

wMelPop infections in females influence the hatch rates of eggs. A generalized linear model (Tweedie with identity link) showed that mating combination (Wald = 17.464, df = 4, P < 0.05), but not male nutrition (Wald = 3.081, df = 1, P = 0.079) or interactions between these factors (Wald = 3.3173, df = 4, P = 0.529), affected the hatch rates of eggs. No significant difference was observed between wild-type females and wMel-infected females regardless of male infection status. More eggs hatched from wild-type females than from wMelPop-infected females. No difference was observed between wMelPop and wMel-infected females (Figure 2, Table 3).

Figure 2.

Mean fecundity ± SEM. Significant difference between lines *P < Holm-Bonferroni α. Both the wMel (MGYP2.out) and wMelPop (A.PGYP1.out) strains of Wolbachia reduced the fecundity of infected Ae. aegypti.

Table 3.

Statistics table comparing hatch rate of eggs of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected mosquitoes

| Line 1 | Line 2 | Z | P | Holm-Bonferroni α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPO |

WTWT |

2.271 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

| POWT |

WTWT |

2.084 |

0.000 |

0.005 |

| POPO |

POWT |

1.683 |

0.007 |

0.006 |

| MOMO |

POPO |

1.470 |

0.027 |

0.007 |

| MOMO |

POWT |

1.373 |

0.046 |

0.008 |

| MOWT |

WTWT |

1.231 |

0.097 |

0.010 |

| MOMO |

WTWT |

1.352 |

0.052 |

0.012 |

| MOWT |

POPO |

1.330 |

0.058 |

0.017 |

| MOWT |

POWT |

1.210 |

0.107 |

0.025 |

| MOMO | MOWT | 0.610 | 0.850 | 0.050 |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is significant if P < Holm-Bonferroni α.

Re-mating success of males

When males were allowed to mate for a second time, with new cohorts of females, few females were successfully mated ( = 1.6, SEM = 0.280). A generalized linear model (Poisson with log link) showed that wMelPop infection (Wald = 0.695, P = 0.707), male larval nutrition (Wald = 1.969, P = 0.161) and interactions between these factors did not affect the number of females that laid eggs. Generalized linear models (Tweedie with identity link) showed that fecundity (F) and hatch rates of eggs (H) were not significantly affected by wMelPop-infection (F: Wald = 1.64, P = 0.441; H: Wald = 2.704, P = 0.259), male larval nutrition (F: Wald = 0.969, P = 0.325; H: Wald = 0.98, P = 0.322) or interactions between these factors (F: Wald = 5.089, P = 0.078; H: Wald = 0.199, P = 0.905). These data suggest that most males depleted themselves in the first mating experiment and did not completely renew mating ability by the second mating.

Sperm quantity and viability

Male larval nutrition and Wolbachia infections do not affect the quantity or viability of sperm. The quantity (Q) and viability (V) of sperm produced by males was not affected by wMelPop infection (Q: F = 2.325, P = 0.136; V: F = 2.412, P = 0.129), male larval nutrition (Q: F = 2.382, P =0.131; V: F = 1.79, P = 0.189) or interactions between these factors (Q: F = 0.626, P = 0.434; V: F = 0.475, P = 0.495).

Discussion

Both wMelPop and wMel caused reductions in female fecundity regardless of the infection status of male mates. Males reared on low-nutrition larval diets developed more slowly, were smaller and inseminated fewer females than those reared on high-nutrition larval diets. Interestingly, the fecundity of wMel-infected females was reduced when the mated male, regardless of infection status, had been reared on a low nutrition diet. For wMelPop-infected females, fecundity was consistently low, and was not rescued by the rearing of males on high nutrition like in the case of wMel. The reduced fecundity of wMelPop is not unexpected given the virulence of the infection. The reduction in fecundity of wMel females due to male nutrition, however, has not been previously reported. Wolbachia infection did not affect larval development or male wing length in this study, although, small effects have been reported previously by Yeap et al. [50]. Neither strain of Wolbachia affected sperm quality or viability or the ability of males to successfully mate a second cohort of females.

Female fecundity measurements taken soon after the establishment of the PGYP1 and MGYP2 lines of Ae. aegypti failed to show changes in response to Wolbachia infection [2,3]. However, a subsequent investigation examining the effects of diverse human bloods and non-human bloods on the mosquito revealed a fecundity reduction of 27% for PGYP1 [57]. This estimate is consistent with our measure of 23%. The sudden appearance of a fecundity cost in wMel (19% reduction) could possibly be explained by the use of different human blood feeders for characterisation [57]. Alternatively, these temporal changes in the effects of Wolbachia infection could reflect an increase in the virulence and or changes in the genetic background of the mosquito line.

The possible mechanistic bases for reductions in fecundity are many. Changes in the blood-feeding behaviour of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes could influence the reduced fecundity of infected females. Ae. aegypti seek blood meals to maximise fecundity and reserves [58] and Turley et al. [23] showed that wMelPop-infected mosquitoes imbibe smaller blood meals than uninfected mosquitoes, limiting the resources available for egg synthesis in wMelPop-infected females, and potentially reducing the number and viability of eggs produced. To date, the size of blood meal imbibed by wMel-infected mosquitoes has not been investigated. Therefore, it is possible that the reduced fecundity of Wolbachia-infected females in this study could be explained by reduced blood-feeding abilities of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes.

Another potential explanation for the reduced fecundity of Wolbachia-infected females is the incorrect processing of male accessory reproductive gland proteins. Nuptial gifts are common in insects and seminal gifts – genitally absorbed male donations – are often beneficial to offspring fitness [59-62]. Male accessory reproductive glands produce secretions essential for the transfer of sperm to females during mating. Proteins in these secretions affect female reproductive activity and improve males’ chances of siring females’ offspring. In many insects, egg production and eventual deposition occur at reduced rates in virgin females compared to mated insects, due to the presence of fecundity-enhancing substances in male accessory reproductive gland secretions [63]. Accessory gland reproductive proteins have been shown to increase egg production in Aedes spp. This is thought to be due to stimulation of vitellogenesis, the synthesis and secretion of egg yolk protein precursors by the mosquito fat body [64-67]. Parasites are known to modify vitellogenesis [68,69] and Wolbachia infections are associated with decreases in yolk protein gene expression in previtellogeneic ovaries of Drosophila melanogaster[70]. Therefore, it is possible that Wolbachia infections in Ae. aegypti females could interfere with the processing of male accessory reproductive gland proteins, potentially reducing vitellogenesis and host fecundity.

Reduced viability of wMelPop eggs could be attributed to increased frequency of apoptosis in the female germline cells. This and previous studies have shown that wMelPop infections reduce the hatch rate of eggs laid by Ae. aegypti[50,57]. Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is a process needed for normal development and is a feature of female germline development common to vertebrate and invertebrate species [71-74]. A recent study of D. melanogaster has shown that wMelPop infections increase the frequency of apoptosis in the female germline cells compared to wMel-infected and uninfected lines [75]. Infections with wMelPop could induce similar effects in Ae. aegypti, potentially impacting the development of embryos such that fewer eggs are viable.

The decreases in reproductive success observed in this study may not be sufficiently strong to prevent the spread of Wolbachia into host populations. Population modelling has suggested that up to a 50% reduction in fecundity could be overcome by the expression of strong cytoplasmic incompatibility and still allow spread of Wolbachia[76]. In addition, other, less well understood, benefits of Wolbachia infection, such as Wolbachia-mediated protection against mosquito pathogens, could enhance host fitness. Early studies of Drosophila simulans infected with the Wolbachia strain wRi showed that females infected with this strain were 10-20% less fecund than Wolbachia-cured and wild-type counterparts [77]. Despite this cost, wRi rapidly spread through California populations of D. simulans between 1984 and 1994 [6]. Indeed both the field cage trials [3] and the open field releases for wMel [4] have demonstrated effective spread of this strain into Ae. aegypti populations. Open field releases of the wMelPop only just began in 2012 and are still ongoing.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that males infected with wMel or wMelPop do not suffer a reduced ability to inseminate females. While males in general suffer fitness consequences when reared on low nutrition that for the most part these effects are not made more extreme by the presence of Wolbachia. These findings bode well for the ability of infected males to cause cytoplasmic incompatibility in populations of mixed infection status as in open field releases. Surprisingly, wMel infected females appear to suffer similar reductions in fecundity as wMelPop-infected females, an effect exacerbated by rearing of male mates in low nutrition environments. These reductions in fitness, however, are within the range of what may be mitigated by the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility still allowing for Wolbachia infections to spread.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

AT, MZ, SO and EM designed the study. AT carried out the research. AT, MZ and EM analyzed the data. AT drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Andrew P Turley, Email: andrew.turley@uq.edu.au.

Myron P Zalucki, Email: m.zalucki@uq.edu.au.

Scott L O’Neill, Email: scott.oneill@monash.edu.

Elizabeth A McGraw, Email: beth.mcgraw@monash.edu.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nichola Kenny for technical support. This research was supported by grants from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Queensland State Government.

References

- Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?–A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281(2):215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AW, Sidhu M, Wang YF, O'Neill SL. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009;323(5910):141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1165326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, McMeniman CJ, Leong YS, Dong Y, Axford J, Kriesner P. et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476(7361):450–453. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, Greenfield M, Durkan M, Leong YS, Dong Y. et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476(7361):454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. Rapid spread of an inherited incompatibility factor in California Drosophila. Nature. 1991;353(6343):440–442. doi: 10.1038/353440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans: dynamics and parameter estimates from natural populations. Genetics. 1995;140(4):1319–1338. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PE, McMeniman CJ, O'Neill SL. Modifying insect population age structure to control vector-borne disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;627:126–140. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78225-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M. et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139(7):1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):e1000833. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser RL, Meola MA. The native Wolbachia endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus increase host resistance to West Nile virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e11977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hurk AF, Hall-Mendelin S, Pyke AT, Frentiu FD, McElroy K, Day A, Higgs S, O'Neill SL. Impact of Wolbachia on infection with Chikungunya and Yellow Fever viruses in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(11):e1892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science. 2009;326(5949):134–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1177531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min KT, Benzer S. Wolbachia, normally a symbiont of Drosophila, can be virulent, causing degeneration and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(20):10792–10796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans O, Caragata EP, McMeniman CJ, Woolfit M, Green DC, Williams CR, Franklin CE, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. Increased locomotor activity and metabolism of Aedes aegypti infected with a life-shortening strain of Wolbachia pipientis. J Exp Biol. 2009;212(Pt 10):1436–1441. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caragata EP, Real KM, Zalucki MP, McGraw EA. Wolbachia infection increases recapture rate of field-released Drosophila melanogaster. Symbiosis. 2011;54(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- De Crespigny FEC, Pitt TD, Wedell N. Increased male mating rate in Drosophila is associated with Wolbachia infection. J Evol Biol. 2006;19(6):1964–1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Crespigny FEC, Wedell N. Wolbachia infection reduces sperm competitive ability in an insect. Proc Biol Sci. 2006;273(1593):1455–1458. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 2008;322(5902):702. doi: 10.1126/science.1162418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Nielsen JE, Cunningham JP, McGraw EA. Wolbachia infection alters olfactory-cued locomotion in Drosophila spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(13):3943–3948. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02607-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kubo T, Ishikawa H. Interspecific transfer of Wolbachia between two lepidopteran insects expressing cytoplasmic incompatibility: a Wolbachia variant naturally infecting Cadra cautella causes male killing in Ephestia kuehniella. Genetics. 2002;162(3):1313–1319. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw EA, Merritt DJ, Droller JN, O'Neill SL. Wolbachia density and virulence attenuation after transfer into a novel host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(5):2918–2923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052466499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman CJ, O'Neill SL. A virulent Wolbachia infection decreases the viability of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti during periods of embryonic quiescence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(7):e748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley AP, Moreira LA, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. Wolbachia infection reduces blood-feeding success in the dengue fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(9):e516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira LA, Saig E, Turley AP, Ribeiro JM, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. Human probing behavior of Aedes aegypti when infected with a life-shortening strain of Wolbachia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(12):e568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helinski ME, Valerio L, Facchinelli L, Scott TW, Ramsey J, Harrington LC. Evidence of polyandry for Aedes aegypti in semifield enclosures. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(4):635–641. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC. A study on the fecundity of male Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1973;19(2):435–439. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(73)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choochote W, Tippawangkosol P, Jitpakdi A, Sukontason KL, Pitasawat B, Sukontason K, Jariyapan N. Polygamy: the possibly significant behavior of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in relation to the efficient transmission of dengue virus. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32(4):745–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz RW. Neuro-hormonal regulation of sexual receptivity in female Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1972;18(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(72)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook RR, Cleland SY, Wolfner MF, Karr TL. Offsetting effects of Wolbachia infection and heat shock on sperm production in Drosophila simulans: analyses of fecundity, fertility and accessory gland proteins. Genetics. 2000;155(1):167–178. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti R, Calvitti M. Male mating performance and cytoplasmic incompatibility in a wPip Wolbachia trans-infected line of Aedes albopictus (Stegomyia albopicta) Med Vet Entomol. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- May RM, Anderson RM. Population biology of infectious diseases: Part II. Nature. 1979;280(5722):455–461. doi: 10.1038/280455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, May RM. Population biology of infectious diseases: Part I. Nature. 1979;280(5721):361–367. doi: 10.1038/280361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-De-Freitas R, Codeco CT, Lourenco-De-Oliveira R. Body size-associated survival and dispersal rates of Aedes aegypti in Rio de Janeiro. Med Vet Entomol. 2007;21(3):284–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel H, Knusel I, Timmermann SE. Aedes aegypti: size, reserves, survival, and flight potential. J Vector Ecol. 2001;26(1):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadee DD, Beier JC. Factors influencing the duration of blood-feeding by laboratory-reared and wild Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Trinidad, West Indies. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91(2):199–207. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1997.11813130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue RD, Barnard DR, Schreck CE. Influence of body size and age of Aedes albopictus on human host attack rates and the repellency of deet. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1995;11(1):50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore MS, Lord CC. The relationship between size and fecundity in Aedes albopictus. J Vector Ecol. 2000;25(2):212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naksathit AT, Scott TW. Effect of female size on fecundity and survivorship of Aedes aegypti fed only human blood versus human blood plus sugar. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1998;14(2):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponlawat A, Harrington LC. Age and body size influence male sperm capacity of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2007;44(3):422–426. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[422:AABSIM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook CJ, Lounibos LP. Larval temperature and nutrition alter the susceptibility of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to Chikungunya virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(5):68–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nasci RS, Mitchell CJ. Larval diet, adult size, and susceptibility of Aedes aegypti (Diptera, Culicidae) to infection with Ross River Virus. J Med Entomol. 1994;31(1):123–126. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwanchaichinda C, Paskewitz SM. Effects of larval nutrition, adult body size, and adult temperature on the ability of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) to melanize Sephadex beads. J Med Entomol. 1998;35(2):157–161. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken W, Klowden MJ, Chambers GM. Effect of body size on host seeking and blood meal utilization in Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae): the disadvantage of being small. J Med Entomol. 1998;35(5):639–645. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel H. Fecundity, metabolism, and body size in Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae), vectors of malaria. J Med Entomol. 1990;27(5):839–850. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okanda FM, Dao A, Njiru BN, Arija J, Akelo HA, Toure Y, Odulaja A, Beier JC, Githure JI, Yan G. et al. Behavioural determinants of gene flow in malaria vector populations: Anopheles gambiae males select large females as mates. Malaria J. 2002;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster WA, Takken W. Nectar-related vs. human-related volatiles: behavioural response and choice by female and male Anopheles gambiae(Diptera: Culicidae) between emergence and first feeding. Bull Entomol Res. 2004;94(2):145–157. doi: 10.1079/BER2003288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue RD, Barnard DR. Human host avidity in Aedes albopictus: influence of mosquito body size, age, parity, and time of day. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1996;12(1):58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue RD, Edman JD, Scott TW. Age and body size effects on blood meal size and multiple blood feeding by Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1995;32(4):471–474. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponlawat A, Harrington LC. Factors associated with male mating success of the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(3):395–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap HL, Mee P, Walker T, Weeks AR, O'Neill SL, Johnson P, Ritchie SA, Richardson KM, Doig C, Endersby NM. et al. Dynamics of the “popcorn” Wolbachia infection in outbred Aedes aegypti informs prospects for mosquito vector control. Genetics. 2011;187(2):583–595. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.122390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuval B, Kaspi R, Field SA, Blay S, Taylor P. Effects of post-teneral nutrition on reproductive success of male mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera; Tephritidae) Florida Entomol. 2002;85:165–170. doi: 10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0165:EOPTNO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barry JD, McInnis DO, Gates D, Morse JG. Effects of irradiation on Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae): Emergence, survivorship, lure attraction, and mating competition. J Econ Entomol. 2003;96(3):615–622. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-96.3.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blay S, Yuval B. Nutritional correlates of reproductive success of male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) Animal Behav. 1997;54(1):59–66. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1996.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PW, Yuval B. Postcopulatory sexual selection in Mediterranean fruit flies: advantages for large and protein-fed males. Animal Behav. 1999;58(2):247–254. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trpis M. Autogeny in diverse populations of Aedes aegypti from East Africa. Tropenmed Parasitol. 1977;28(1):77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster WA, Lea AO. Renewable fecundity of male Aedes aegypti following replenishment of seminal vesicles and accessory glands. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21(5):1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman CJ, Hughes GL, O'Neill SL. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti disrupts mosquito egg development to a greater extent when mosquitoes feed on nonhuman versus human blood. J Med Entomol. 2011;48(1):76–84. doi: 10.1603/ME09188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington LC, Edman JD, Scott TW. Why do female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) feed preferentially and frequently on human blood? J Med Entomol. 2001;38(3):411–422. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs C. In: Insect reproduction. Leather S, Hardie J, editor. New York: CRC Press; 1995. Male nuptial gifts: phenotypic consequences and evolutionary implications; pp. 215–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gwynne D. Katydids and bush crickets: reproductive behaviour and evolution of the Tettigoniidae. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R. Sexual selection and paternal investment in insects. Am Nat. 1976;110:153–163. doi: 10.1086/283055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vahed K. The function of nuptial feeding in insects: review of empirical studies. Biol Rev. 1998;73:43–78. doi: 10.1017/S0006323197005112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel T, Gillott C. Contribution of male-produced proteins to vitellogenesis in Melanoplus sanguinipes. J Insect Physiol. 1977;23(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(77)90120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attardo GM, Hansen IA, Raikhel AS. Nutritional regulation of vitellogenesis in mosquitoes: implications for anautogeny. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35(7):661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovsky D. The role of the male accessory-gland fluid in stimulating vitellogenesis in Aedes taeniorhynchus. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1985;2(4):405–413. doi: 10.1002/arch.940020408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downe AER. Internal regulation of rate of digestion of blood meals in mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21(11):1835–1839. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden MJ, Chambers GM. Male accessory-gland substances activate egg development in nutritionally stressed Aedes aegypti mosquitos. J Insect Physiol. 1991;37(10):721–726. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(91)90105-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd H, Webb TJ. Parasites and pathogens: effects on host hormones and behaviour. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw M, Hurd H. The effects of Onchocerca lienalis infection on vitellogenesis in the British blackfly, Simulium ornatum. Parasitol. 1994;109(Pt 3):337–343. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000078367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Cline TW. Effects of Wolbachia infection and ovarian tumor mutations on Sex-lethal germline functioning in Drosophila. Genetics. 2009;181(4):1291–1301. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.099374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC. Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell. 1997;88(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Tower J. Programmed cell death and apoptosis in aging and life span regulation. Discov Med. 2009;8(43):223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall K. Eggs over easy: cell death in the Drosophila ovary. Dev Biol. 2004;274(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Findlay JK, Hutt KJ, Kerr JB. Apoptosis in the germ line. Reproduction. 2011;141(2):139–150. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukova MV, Kiseleva E. The virulent Wolbachia strain wMelPop increases the frequency of apoptosis in the female germline cells of Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12(Suppl 1):S15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-S1-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in populations with overlapping generations. Evolution. 2010;64(1):232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Turelli M, Harshman LG. Factors affecting the distribution of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans. Genetics. 1990;126:933–948. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]