Background: Cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) is the covalent ligation of heme b to an apocytochrome c.

Results: CcmE forms a stable ternary complex with CcmI and apocytochrome c.

Conclusion: Together with CcmFHI, the heme chaperone CcmE is a part of the heme ligation complex that matures apocytochromes c.

Significance: These findings contribute to our mechanistic understanding of how the Ccm process occurs in cells.

Keywords: Bioenergetics/Electron Transfer Complex, Cytochrome c, Heme, Photosynthesis, Posttranslational Modification, Cytochrome c Maturation, Rhodobacter capsulatus, Apocytochrome Chaperone, Heme Chaperone, Protein-Protein Interactions

Abstract

Cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) is a post-translational process that occurs after translocation of apocytochromes c to the positive (p) side of energy-transducing membranes. Ccm is responsible for the formation of covalent bonds between the thiol groups of two cysteines residues at the heme-binding sites of the apocytochromes and the vinyl groups of heme b (protoporphyrin IX-Fe). Among the proteins (CcmABCDEFGHI and CcdA) required for this process, CcmABCD are involved in loading heme b to apoCcmE. The holoCcmE thus formed provides heme b to the apocytochromes. Catalysis of the thioether bonds between the apocytochromes c and heme b is mediated by the heme ligation core complex, which in Rhodobacter capsulatus contains at least the CcmF, CcmH, and CcmI components. In this work we show that the heme chaperone apoCcmE binds to the apocytochrome c and the apocytochrome c chaperone CcmI to yield stable binary and ternary complexes in the absence of heme in vitro. We found that during these protein-protein interactions, apoCcmE favors the presence of a disulfide bond at the apocytochrome c heme-binding site. We also establish using detergent-dispersed membranes that apoCcmE interacts directly with CcmI and CcmH of the heme ligation core complex CcmFHI. Implications of these findings are discussed with respect to heme transfer from CcmE to the apocytochromes c during heme ligation assisted by the core complex CcmFHI.

Introduction

Cytochromes c are ubiquitous heme proteins found in most living organisms. They contain at least one protoporphyrin IX-Fe (heme b) cofactor that is stereo-specifically attached to the polypeptide chain via two thioether bonds. These bonds are formed posttranslationally between the vinyl groups of the heme tetrapyrrole ring and the thiol groups of the cysteine residues at the conserved heme-binding site(s) (C1XXC2H) within the apocytochromes (1, 2). In α- and γ-proteobacteria, including Rhodobacter capsulatus, cytochrome c maturation (Ccm)2 occurs extracytoplasmically and involves 10 membrane-associated proteins (CcmABCDEFGHI and CcdA) with specific roles (see Fig. 1 and listed in supplemental Table S1). Of these components, CcdA and CcmG are thiol oxidoreductases that are implicated in the reduction of the disulfides bonds at the heme-binding sites of the apocytochromes c. CcmA, CcmB, CcmC, and CcmD form an ABC-type transporter that is responsible for conveying heme to the periplasm and loading it into CcmE (for reviews, see Refs. 1, 3, and 4). HoloCcmE binds covalently to the vinyl-2 of heme via an essential His residue located at its own heme-binding motif (HXXXY) and subsequently delivers heme to the apocytochrome c substrates (5, 6). Formation of the thioether bonds is thought to occur at the heme ligation core complex, which contains at least the CcmF, CcmH and CcmI components in R. capsulatus (7) (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S1).

FIGURE 1.

Overall organization of R. capsulatus Ccm system I. After translocation to the periplasm via the SEC system, a pre-apocytochrome c is processed to an apocytochrome c that undergoes a series of thio-redox reactions. The heme-binding site cysteines can be oxidized by DsbA to form an intramolecular disulfide bond. CcdA together with CcmG and/or CcmH are responsible for resolving this disulfide bond, rendering the apocytochrome ligation-competent (left panel). Heme b is produced in the cytoplasm, and CcmABCDE proteins mediate its translocation and relay to the ligation site. CcmE is a heme chaperone that binds heme covalently via a conserved His residue. Heme-loaded holoCcmE is released from its partners (right panel) to transfer heme to apocytochrome c together with the heme ligation core complex CcmFHI (middle panel). CcmI binds to the C-terminal portion of the apocytochrome c substrates via its large periplasmic domain. CcmF is a heme b-containing protein that is thought to reduce the heme in holoCcmE to facilitate its release to the apocytochrome c. WWD refers to a tryptophan (W) rich domain.

The heme chaperone CcmE has an N-terminal membrane anchor followed by a large periplasmic domain with a rigid β-barrel core structure and a flexible C-terminal extension (8, 9). It belongs to the oligo-binding-fold family of proteins in which the C-terminal helix is often involved in protein-protein interactions (10).

Previously, CcmE was shown to form a complex with CcmC and CcmD in the absence of CcmAB. This complex contained oxidized heme (Fe3+) covalently bound to the His residue of CcmE, with CcmC providing two additional His residues as axial ligands of the heme iron (11).

Besides CcmC and CcmD, CcmF that forms together with CcmH the heme ligation core complex in E. coli was shown to interact with CcmE (12, 13). CcmF is a large multispan membrane protein with a b-type heme (11) and belongs to the heme handling protein (HHP) family like CcmC (supplemental Table S1) (14). Recently, it has been suggested that CcmF reduces the heme of holoCcmE to facilitate its transfer to the apocytochrome c (11, 15). In α-proteobacteria (e.g. R. capsulatus), although CcmF is similar to its Escherichia coli counterpart, CcmH is different and has a single transmembrane helix attached to a periplasmic domain with a thioredoxin-like motif (16). However, these species contain an additional component, CcmI (supplemental Table S1), which is a bipartite protein with a membrane integral domain (CcmI-1) composed of two transmembrane helices linked through a cytoplasmic loop with a leucine zipper-like motif. Interestingly, the second domain (CcmI-2) of CcmI, which has three tetratricopeptide (TPR) repeats, is homologous to the C-terminal periplasmic extension of E. coli CcmH (17), rendering E. coli CcmFH and R. capsulatus CcmFHI heme ligation core complexes highly similar.

Recently, a ternary complex formed by CcmE, heme, and a C1XXXH-containing c-type variant of E. coli cytochrome b562 has been identified. The heme was covalently ligated to both CcmE and apocytochrome b562 variant via the His and Cys residues, respectively. A similar complex was also obtained in vitro using the Hydrogenobacter thermophilus apocytochrome c552 (18).

Previously, we showed that CcmI functions as an apocytochrome c chaperone as it binds tightly to the C-terminal helical portion of apocytochrome c2 via its periplasmic CcmI-2 domain. CcmI was suggested to capture apocytochrome c and to facilitate heme ligation carried out by CcmFHI (19). We pursued our studies by investigating how CcmE recognizes the apocytochromes using the apocytochrome form of R. capsulatus cytochrome c2 as a substrate and how it interacts with the components of the heme ligation core complex. In the present study we expressed in E. coli and affinity-purified the R. capsulatus CcmE, CcmI, and apocytochrome c2 proteins and their appropriate mutant derivatives. Using reciprocal in vitro protein-protein interaction assays combined with size exclusion chromatography, we showed for the first time that R. capsulatus apoCcmE interacts directly with apocytochrome c2 in the absence of heme. In contrast with CcmI, which recognizes the C-terminal helical region of apocytochrome c2, apoCcmE has higher affinity for the apocytochrome c2 when a disulfide is present at its heme-binding site. In addition, apoCcmE also binds CcmI, and together with apocytochrome c2 they form a stable ternary complex in vitro. Finally, using detergent-dispersed membranes, we showed that R. capsulatus apoCcmE interacts with the heme ligation core complex components CcmH and CcmI and discuss these findings in the context of the Ccm process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are described in Table 1. R. capsulatus strains were grown chemoheterotrophically (i.e. by respiration) at 35 °C on enriched mineral-peptone-yeast extract medium supplemented with tetracycline or spectinomycin at 2.5 and 10 μg/ml final concentration, respectively (20). E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37 °C and 200 rpm in Luria-Bertani broth medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Cultures were induced at A600 of 0.6-0.8 by the addition of 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 4–6 h at 37 °C for FLAG-CcmI, His-CcmI, and Strep-apocytochrome c2, and for 16–18 h at room temperature for His-apoCcmE production.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

Res and Ps refer to respiratory and photosynthetic growth, respectively. Nadi refers to cytochrome c oxidase-dependent catalysis of α-naphthol to indophenol blue. MedA under “Relevant characteristics,” refers to Sistrom's minimal medium A. R. capsulatus MT1131 strain is referred to as a wild-type strain with respect to its cytochrome c profile and growth properties.

| Strains/Plasmids | Relevant characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| R. capsulatus | ||

| MTSRP1.r1 | Δ(ccmI::kan) G448A in promoter of ccmFH; Res+ Nadi+ Ps+, cyt c+ on MedA | (46) |

| MT1131 | Wild type, ctrD121 Rifr; Res+ Nadi+ Ps+ | (47) |

| MD2 | Δ(ccmE::spec); Res+ Nadi− Ps− | (48) |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| HB101 | F− Δ (gpt-proA)62 araC14 leuB6(Am) glnV44(AS) galK2(Oc) lacY1 Δ (mcrC-mrr) rpsL20(Strr) xylA5 mtl-1 thi-1 | Stratagene |

| XL1-Blue | endA1 gyrA96(NalR) thi-1 recA1 relA1 lac glnV44 F'[::Tn10 proAB+ lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15] hsdR17(rK− mK+) | Stratagene |

| RP4182 | trp, gal, rpsL Δ (supE, dcm, fla) | (49) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK415 | Broad host-range vector, gene expression supported by E. coli lacZ promoter, Tetr | (50) |

| pAV1 | R. capsulatus cycA encoding mature cytochrome c2 with a N-terminal Strep tag, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV1C13S | Cys13 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV1 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV1C16S | Cys16 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV1 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV1H17S | His17 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV1 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV1M96S | Met96 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV1 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV1C13SC16S | Cys13 and Cys16 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV1 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV2 | pAV1 derivative with an in-frame stop codon (TAA) 78 bp upstream of the native TAG codon, deleting the 26 last amino acids of cycA, Ampr | (19) |

| pAV2C13SC16S | Cys-13 and Cys-16 of R. capsulatus cycA in pAV2 mutated to Ser, Ampr | (19) |

| pCS1303 | His10 tag sequence fused to GFP, rendering GFP replaceable by cloning any gene of interest in-frame into NdeI and BamHI sites, Ampr | (19) |

| pMADO5 | R. capsulatus ccmI encoding full length CcmI with a N-terminal His10 tag sequence, Ampr | (19) |

| pFLAG-CcmI | pMADO5 derivative, with a N-terminal Flag tag sequence instead of the His10 tag, Ampr | This work |

| pAV4 | pCS1303 derivative containing R. capsulatus ccmE encoding full length CcmE with a N-terminal His10 tag sequence, Ampr | This work |

| pAV4H123A | His123 of R. capsulatus ccmE in pAV4 mutated to Ala, Ampr | This work |

| pNJ2 | ccmI::FLAG expressed from its own promoter in pRK415, Tetr | (17) |

Plasmids

Molecular genetic techniques were performed according to Sambrook et al. (21). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing and analyzed using the Serial Cloner 2.1 and BLAST software. Nucleotide sequences of the primers used are described in supplemental Table S2). The full-length ccmE gene was PCR-amplified from R. capsulatus MT1131 (Table 1) genomic DNA using the primers CcmE-NdeI-Fw and CcmE-BamHI-Rv, inserting at the N and C terminus of CcmE the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. This PCR product was then cloned into pCS1303 (19) using the same restriction sites. The plasmid pAV4 thus obtained contains an in-frame 10 histidine-long (His) epitope tag followed by the Factor Xa cleavage site fused to the N terminus of CcmE. Plasmid pAV4H123A, containing the His-123 to Ala substitution, was generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with pAV4 as a template and CcmEH123A-Fw and CcmEH123A-Rv as mutagenic primers. A FLAG-tagged version of full-length CcmI was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using the primers FLAG-Fw and FLAG-Rv and pMADO5 as a template (19). The plasmid pFLAG-CcmI thus constructed contained a FLAG epitope tag followed by the Factor Xa cleavage site fused to the N terminus of CcmI. Plasmid pMADO5 was used for production and purification of a His-tag version of CcmI, as described earlier (19). The apocytochrome c2 and its derivatives were obtained as described previously (19), and all contained an N-terminal in-frame Strep-tag II-epitope tag followed by the Factor Xa cleavage site.

Preparation of R. capsulatus or E. coli Detergent-solubilized Membrane Proteins

R. capsulatus or E. coli solubilized membrane proteins were obtained as described previously (19). Briefly, intracytoplasmic membrane vesicles were prepared using a French pressure cell. The membrane pellets were obtained after 2 h of centrifugation at 4 °C and 138,000 × g. Membranes were dispersed by the addition of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) (Anatrace, Inc.) at a protein:detergent ratio of 1:1 (w/w) under continuous stirring for 1 h at 4 °C followed by another high speed centrifugation to remove non-solubilized proteins.

Protein Purification

For purification of His-CcmI (19), His-apoCcmE and its H123A mutant detergent-solubilized E. coli membranes were loaded onto a Ni2+-Sepharose high performance column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with a buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, 40 mm imidazole, and 0.01% DDM. Elution of the His tagged-proteins was done using the same buffer with 500 mm imidazole. Purification of FLAG-CcmI from E. coli solubilized membranes was done using the Anti-FLAG® M2 affinity gel (Sigma) equilibrated with a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.01% DDM. Elution was done with a buffer containing 100 mm glycine, pH 3.5, and 0.01% DDM. After elution, samples were immediately neutralized by the addition of a few μl of 1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Purifications of Strep-apocytochrome c2 and its mutant derivatives were performed as described previously (19). After SDS-PAGE analysis, protein fractions were concentrated and desalted with a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) using a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl with 0.01% DDM. The identity of purified proteins was confirmed routinely by nLC-MS/MS spectroscopy as described earlier (19).

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies Using Reciprocal Co-purification Assays

Protein-protein interactions between His-apoCcmE, Strep-apocytochrome c2, FLAG-CcmI, and their respective derivatives were assayed as described before (19). Briefly, purified His-apoCcmE (10 μg), Strep-apocytochrome c2 (15 μg), and FLAG-CcmI (10 μg) were mixed as appropriate in a binding/wash buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 50 mm imidazole, and 0.01% DDM (final assay volume of 400 μl) and incubated for 2 h at 25 °C with gentle shaking. When required, 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mm diamide, 1 mm CuCl2 or 1 mm H2O2 were added to the assay mixture. After incubation, the assay mixture was loaded to 200 μl of either Strep-Tactin or Ni2+-Sepharose resin columns, equilibrated with wash buffer, and washed extensively. Elution of the interacting partners from the Strep-Tactin or Ni2+-Sepharose columns was performed using appropriate wash buffers containing 2.5 mm desthiobiotin or 500 mm imidazole, respectively. Flow-through and elution fractions were precipitated with methanol:acetone (7:2, v/v) overnight at −20 °C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. For binding assays using DDM-dispersed R. capsulatus membranes, 500 μg of total membrane proteins were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 20 μg of His-apoCcmE or His-CcmI in the presence of protease inhibitors mixture (Sigma). After loading the incubation mixtures into a Ni2+-Sepharose column, washing and elution steps were performed as above, and the elution fractions were concentrated and analyzed by immunoblots.

Gel Exclusion Chromatography

Protein-protein interactions were also tested by size exclusion chromatography using a 120-ml Sephacryl S-200 column (GE Healthcare) in the presence of various DDM concentrations. Before use the column was calibrated using bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and horse heart cytochrome c (12.4 kDa) as standards, and its void volume was determined using blue dextran (2000 kDa). His-apoCcmE, FLAG-CcmI, and Strep-apocytochrome c2 were incubated under the co-purification assays conditions described above and loaded into the Sephacryl S-200 column previously equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm NaCl and 0.01% DDM. Similar protein mixtures were also separated using the same buffer but containing 0.05 or 0.2% DDM to confirm that the elution profiles were unaffected by the detergent concentration under the conditions used. Protein profiles of the elution fractions were monitored at 280 nm and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Reduction and Alkylation of the Heme-binding Site Cys Residues from Strep-apocytochrome c2 and Its Single Cysteine Mutants

Strep-apocytochrome c2 and its C13S and C16S Cys mutants were treated with DTT and iodoacetamide as described elsewhere (19).

Antibodies Production

Nickel affinity chromatography purified R. capsulatus His-CcmE (∼ 3 mg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE, electro-eluted from the gel matrix, and used as an antigen for rabbit polyclonal antibodies production that was carried out by Open Biosystems, Inc.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot Analyses

SDS-PAGE was performed using 15% gels according to Laemmli (22), and hemoproteins containing covalently bound heme were detected using tetramethylbenzidine as in Thomas et al. (23). For CcmE, CcmI, CcmF, and CcmH immunodetection, gel-resolved proteins were electroblotted onto Immobilon-PVDF membranes (Millipore Inc.) and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for R. capsulatus Ccm proteins. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare Inc.) were used as secondary antibodies, and detection was performed using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate® from Thermo Scientific, Inc.

Chemicals

All chemicals and solvents were of high purity and HPLC spectral grades and purchased from commercial sources.

RESULTS

Heterologous Expression and Purification of ApoCcmE and Apocytochrome c2

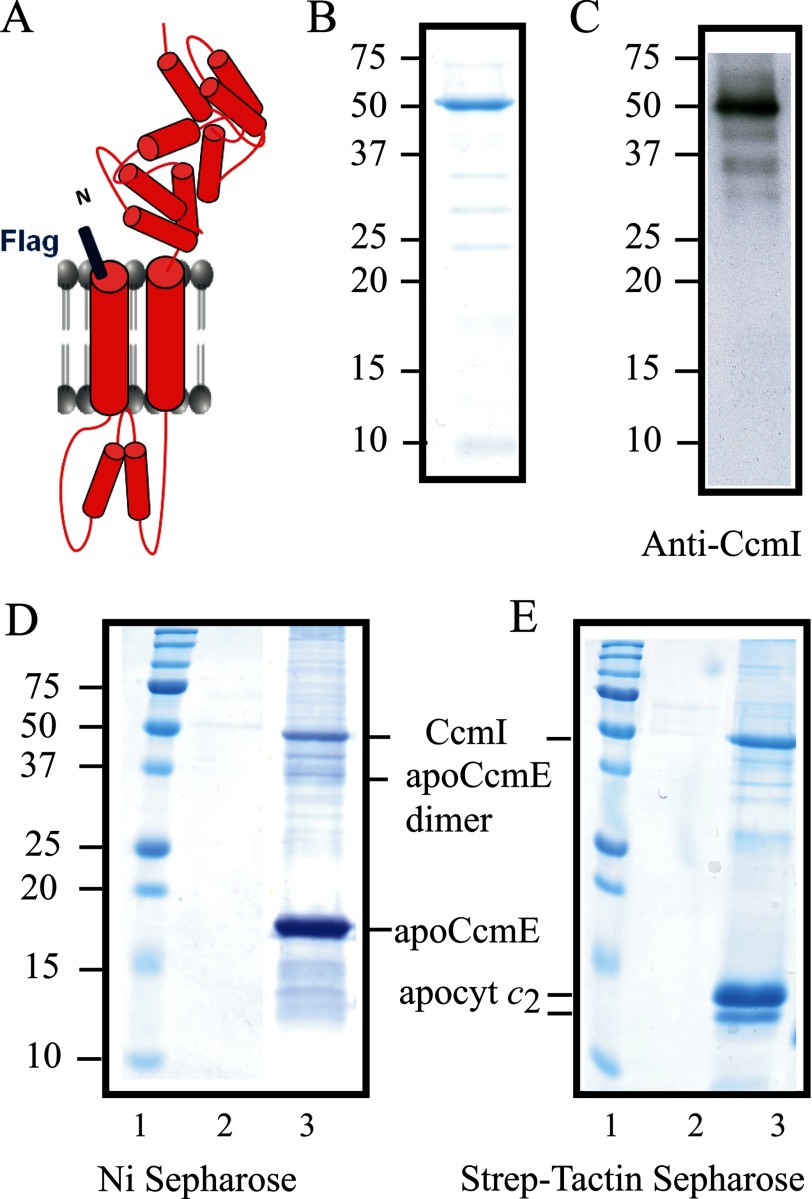

To investigate whether and, if so, how the heme chaperone apoCcmE interacts with apocytochrome c and other Ccm components, including the CcmFHI complex, we produced in E. coli an N-terminal His epitope-tagged full-length R. capsulatus CcmE (His-apoCcmE) and its H123A mutant (His-apoCcmE-H123A) (Fig. 2A) (“Experimental Procedures” and Table 1). These proteins were purified from the membrane fractions of E. coli cells grown aerobically to avoid holoCcmE production by the host Ccm machinery. Purified materials were assessed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses using specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies. By Coomassie staining, His-apoCcmE (Fig. 2B) (and its His-apoCcmE-H123A mutant; data not shown) showed a major band at ∼18 kDa and a minor band (roughly 15%) around 37 kDa. Purified proteins did not contain any heme, based on SDS-PAGE/tetramethylbenzidine staining and on visible spectroscopy (data not shown). The 37-kDa band was attributed to a dimeric form of His-apoCcmE that persisted under reductive SDS-PAGE conditions, as identified using specific anti-apoCcmE polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 2C) and nanoLC-tandem mass spectrometry (data not shown). A tiny amount of His-apoCcmE degradation product (∼15 kDa, not visualized by SDS-PAGE) was also detected by immunoblot (Fig. 2C). A similar, highly stable holoCcmE dimer has been reported previously (18, 24), and our data with the apoCcmE derivative indicated that the presence of heme is not required for this oligomerization.

FIGURE 2.

Purification of R. capsulatus apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2. A, a schematic representation of His-apoCcmE shows its membrane anchor and its periplasmic domain forming a β-barrel fold. The conserved His-123 residue that binds heme covalently is depicted at the surface of the β-barrel. B, Coomassie Blue staining of purified His-apoCcmE with its major monomeric (18 kDa) and minor dimeric (37 kDa) forms is shown. C, shown is an immunoblot of purified His-apoCcmE using anti-CcmE antibodies, with major bands at 18 and 37 kDa; upon overexposure trace amounts of a degradation product of His-apoCcmE, located around 15 kDa (marked with • and not readily visible by Coomassie Blue staining), is also detected. D, a schematic representation of Strep-apocytochrome c2 with its conserved heme-binding site located close to its N terminus shows its random coil conformation in the absence of heme. E, shown is Coomassie Blue staining of purified wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 (wt) and its truncated mutant variant (t26) lacking its last C-terminal 26-amino acid residues. Purified wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 shows a minor band of lower molecular mass corresponding to a C-terminally truncated degradation product (marked with an asterisk). Molecular markers (kDa) are shown.

We also produced in E. coli cytoplasm the N-terminally Strep-epitope tagged full-length R. capsulatus apocytochrome c2 (Fig. 2D) as well as its various mutant derivatives as Ccm substrates (Table 1). These Ccm substrates were purified using Strep-Tactin-Sepharose affinity chromatography as described previously (19). Like many apocytochromes, full-length Strep-apocytochrome c2 was highly prone to degradation during its production and purification even in the presence of protease inhibitors (19). Purified Strep-apocytochrome c2 showed a major band of 13.5 kDa and a minor band of 12.9 kDa (roughly 20%) (Fig. 2E, lane 1), identified using anti-cytochrome c2 polyclonal antibodies and nanoLC-tandem mass spectrometry (data not shown) as a C-terminally truncated derivative with an intact N-terminal Strep tag. This degradation product was not detectable in the case of the t26-Strep-apocytochrome c2 variant of 11.5 kDa, which lacks the last C-terminal 26 amino acid residues (Fig. 2E, lane 2). His-apoCcmE and Strep-apocytochrome c2 proteins thus purified as well as their mutant derivatives were of sufficient purity (over 95%) to carry out reliably co-purification assays analyzed by SDS/PAGE-Coomassie staining and did not contain any unrelated protein.

ApoCcmE Interacts Directly with Apocytochrome c2 in the Absence of Heme

Direct physical interactions between apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2 in the absence of heme were probed using in vitro reciprocal co-purification assays, as carried out previously with CcmI (19). Purified His-apoCcmE (or His-apoCcmE-H123A mutant) was incubated with Strep-apocytochrome c2 and subjected to co-purification assays using tag specific affinity chromatography, and the elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Control experiments showed no unspecific binding of His-apoCcmE to the Strep-Tactin or of Step-apocytochrome c2 to Ni2+-Sepharose columns under the conditions used (Fig. 3A, lane 2, and B, lane 4). In contrast, upon incubation of His-apoCcmE with Strep-apocytochrome c2, the two proteins were co-eluted from either of the tag-affinity columns (Fig. 3A, lane 3, and 3B, lane 2), indicating that apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2 interacted with each other to form a stable binary complex. We noted that the minor band corresponding to the C-terminal-truncated form of apocytochrome c2 also co-purified with apoCcmE, suggesting that the C-terminal portion of apocytochrome c2 was not critical for these interactions (Fig. 3A, lane 3). Moreover, co-purification of Strep-apocytochrome c2 with the His-apoCcmE-H123A mutant derivative indicated that these interactions were not abolished by the absence of the heme binding His residue (Fig. 3B, lane 3), further confirming their independence of heme.

FIGURE 3.

Co-purification of R. capsulatus apoCcmE with apo and holo forms of cytochrome c2. Shown are co-purification of Strep-apocytochrome c2 with His-apoCcmE using Ni2+-Sepharose resin (lane 3) (A) and reciprocal co-purification of His-apoCcmE (lane 2) or His-apoCcmE-H123A mutant variant (lane 3) with Strep-apocytochrome c2 using Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin (B). Strep-apocytochrome c2 (panel A, lane 2) and His-apoCcmE (panel B, lane 4) are not retained unspecifically with Ni2+-Sepharose and Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resins, respectively. Both the intact and the C-terminally truncated forms of apocytochrome c2 are indicated. C, binding of His-apoCcmE to wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 is salt-dependent. Different concentrations of NaCl, 50 mm (lane 1), 150 mm (lane 2), and 250 mm (lane 3) were used during the incubation mixture before co-purification using the Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin. The relative amount of His-CcmE that co-purified with wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 (lane 1) was taken as 100% for image quantification using Image J program and compared with the amounts seen with different salt concentrations. D, R. capsulatus holocytochrome c2 does not co-purify with His-apoCcmE using Ni2+-Sepharose resin. Note the presence in the flow-through (FT; lane 1) and the absence in the elution fraction (E; lane 2) of holocytochrome c2. All co-purification assays were done using the standard assay conditions described under “Experimental Procedures.” Panel C and D show only the regions of the gel containing the two forms of apocytochrome c2 or holocytochrome c2 and the major monomeric form of apo-CcmE for the sake of clarity. Molecular markers (kDa) are shown as needed.

We also carried out binding assays under various salt concentrations to characterize the nature of the apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2 interactions. Increasing NaCl concentrations from 50 to up to 250 mm decreased substantially the amount of His-apoCcmE that co-purified with Strep-apocytochrome c2 (Fig. 3C). Concentrations higher than 250 mm NaCl were not used, as they interfered with the retention of the Strep-apocytochrome c2 by the Strep-Tactin-Sepharose column (data not shown). The data indicated that the interactions of apocytochrome c2 with apoCcmE were sensitive to high salt concentrations, unlike those seen previously with CcmI (19).

Next, we investigated whether apoCcmE could also recognize mature cytochrome c2 with its covalently bound heme. Under the standard assay conditions, when His-apoCcmE was incubated together with cytochrome c2 purified from R. capsulatus periplasmic fractions (25), no cytochrome c2 was retained by the Ni2+-Sepharose resin column binding His-apoCcmE (Fig. 3D). Therefore, apoCcmE recognized apocytochrome c2, but not holocytochrome c2, to form a stable binary complex in vitro under our assay conditions.

Structural Determinants Responsible for ApoCcmE and Apocytochrome c2 Interactions

The data indicating that apoCcmE interacted with apocytochrome c2 in vitro in the absence of heme led us to inquire the molecular determinants responsible for these interactions. We thought that the specific regions of these proteins involved in these interactions might be important for transferring heme from CcmE to apocytochrome c. R. capsulatus cytochrome c2, like the H. thermophilus cytochrome c552, recently shown to form a ternary complex in vitro with CcmE and heme (18), belongs to the Class I of c-type cytochromes (26). These c-type cytochromes have a N-terminally located heme binding (C1XXC2H) motif, a C-terminally located Met residue acting as the sixth axial ligand of the heme-iron, and a general globular fold with interacting N- and C-terminal helices (27, 28). These salient features of apocytochrome c2 were probed for their role(s) in the interactions with apoCcmE.

Heme-binding Site Cys Residues

Participation of the heme-binding site (C13XXC16H) Cys residues of apocytochrome c2 in apoCcmE interactions was examined by using appropriate Strep-apocytochrome c2 mutants. Binding of purified Strep-apocytochrome c2 variant proteins (i.e. -C13S, -C16S, -C13S/C16S) to His-apoCcmE was probed by affinity co-purification using the Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin as done with the native Step-apocytochrome c2. Image analyses of Coomassie Blue-stained gels indicated that apoCcmE still co-purified with apocytochrome c2 mutants lacking either one of the heme-binding site Cys residues (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 7), but in the absence of both Cys residues the amount of apoCcmE that co-purified decreased drastically to ∼15% that determined for the native apocytochrome c2 (Fig. 4A, lane 5). Moreover, with native apocytochrome c2 or its single cysteine mutants treated with DTT/iodoacetamide, we observed that alkylation of the Cys residues is as damaging for apoCcmE-apocytochrome c2 interactions (Fig. 4A, lanes 2, 4, and 8) as the absence of the Cys residues (Fig. 4A, lane 5). Thus, at least one reactive Cys residue at apocytochrome c heme-binding site appeared critical for its recognition by apoCcmE. Considering that the single Cys mutants of apocytochrome c2 can still form intermolecular disulfides, we carried out the co-purification assays in the presence of either reducing or oxidizing agents. In the presence of DTT the amount of apoCcmE that co-purified with apocytochrome c2 decreased to ∼35% that observed in the absence of a reductant (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2). On the other hand, in the presence of diamide, CuCl2, or H2O2, this amount remained unchanged or increased slightly (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–6). The data therefore suggested that apoCcmE preferred to bind to an apocytochrome c2 with a disulfide bond rather than reduced thiols at its heme-binding site.

FIGURE 4.

Co-purification of apoCcmE with various apocytochrome c2 mutants. A, co-purifications of His-apoCcmE with wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 (lanes 1 and 6), single C16S (lane 3), single C13S (lane 7), double C13S/C16S (lane 5) Cys mutants and their respective DTT reduced/iodoacetamide alkylated derivatives, wt* (lane 2), C16S* (lane 4), C13S* (lane 8) are shown. B, co-purification of His-apoCcmE with wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 in the presence of 10 mm DTT (lane 2), 5 mm diamide (DMD; lane 4), 1 mm CuCl2 (lane 5), and 1 mm H2O2 (lane 6) are shown together with untreated samples (no addition (NA)), lanes 1 and 3). C, co-purification of His-apoCcmE with wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 (lane 1 and 3), and H17S (lane 2), M96S (lane 3) heme iron axial ligand mutants and the t26-truncated derivative of Strep-apocytochrome c2 lacking its last 26-amino acid residues (lane 5) as well as its double cysteine mutant t26-C13S/C16S (lane 6) are shown. In panels A–C, the relative amount of His-apoCcmE co-purified with wild type Strep-apocytochrome c2 was taken as 100% for image quantification using Image J program and used for comparison with the amounts seen in the other lanes. All co-purification assays were done under the standard conditions and used Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Panel A and B show the regions of the gel containing the two forms of apocytochrome c2 and the major monomeric form of CcmE for the sake of clarity.

Heme-iron Atom Axial Ligands His-17 and Met-96

We next tested the interactions of Strep-apocytochrome c2 derivatives lacking the heme-iron axial ligands His-17 or Met-96 with His-apoCcmE. Co-purification data showed that apoCcmE co-purified with these mutants at amounts comparable with those observed with the native apocytochrome c2 (Fig. 4C, lanes 1–3). Thus, the heme-iron axial ligands were not important for apoCcmE-apocytochrome c2 interactions.

The C-terminal α-Helix of Apocytochrome c2

Previously, we found that the C-terminal helix of apocytochrome c2 was critical for its recognition by the apocytochrome c chaperone CcmI (19). We tested whether a truncated apocytochrome c2 derivative lacking its last C-terminal 26 amino acids residues and its variant lacking the heme-binding site Cys also interacted with apoCcmE. Co-purification assays similar to those carried out with native Strep-apocytochrome c2 indicated that the amounts of His-apoCcmE that co-purified with truncated Strep-t26-apocytochrome c2 and its Cys-less derivative decreased to ∼75% and ∼15% that observed with native Strep-apocytochrome c2, respectively (Fig. 4C, lanes 4–6). The data demonstrated that the C-terminal portion of apocytochrome c2 is not critical for its interactions with apoCcmE, sharply contrasting the behavior of CcmI (19). It thus appeared that apoCcmE and CcmI interacted with two different portions of apocytochrome c2, namely the heme binding and the C-terminal helix regions, respectively.

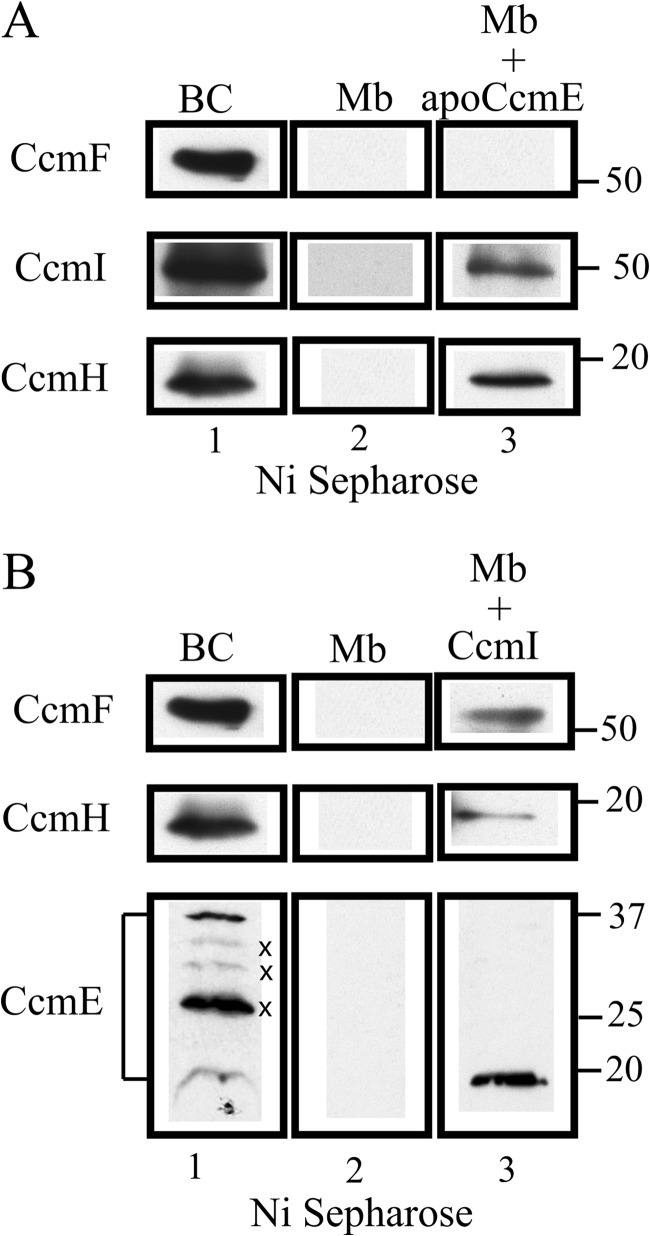

ApoCcmE Interacts with the Heme Ligation Component CcmI in Vitro

Considering that both CcmI and apoCcmE interacted with apocytochrome c2, we inquired whether or not they also interacted with each other. We constructed an N-terminally FLAG epitope tagged full-length CcmI containing both its membrane-anchored (CcmI-1) and periplasmic (CcmI-2) domains (Fig. 5A). FLAG-CcmI purified from solubilized E. coli membranes (“Experimental Procedures”) showed a single band centered around 50 kDa, as judged by Coomassie staining after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5B). Anti-CcmI antibodies detected additional small amounts of FLAG-CcmI degradation products, which are known to occur at its TPR motifs (19) (Fig. 5C). Control experiments indicated that purified FLAG-CcmI alone was not retained in the Ni2+-Sepharose resin unless it was co-incubated with His-apoCcmE (Fig. 5D, lane 2 and 3). Similar data were also obtained using His-apoCcmE-H126A mutant (supplemental Fig. S1A).

FIGURE 5.

R. capsulatus CcmI co-purifies with apoCcmE. A, a schematic representation of FLAG-CcmI shows its CcmI-1 domain with two transmembrane helices and its TPR containing periplasmic CcmI-2 domain. B, Coomassie Blue staining of purified FLAG-CcmI shows a single band centered at ∼50 kDa. C, an immunoblot of purified FLAG-CcmI using anti-CcmI antibodies shows mainly the 50-kDa band and upon overexposure several very faint bands corresponding to its degradation products. D, shown is co-purification of FLAG-CcmI with His-apoCcmE using Ni2+-Sepharose resin (lane 3). E, co-purification of FLAG-CcmI with Strep-apocytochrome c2 using a Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin (lane 3) is shown. Lanes 2 show that FLAG-CcmI is not retained unspecifically in the Ni2+-Sepharose (panel D) and Strep-Tactin-Sepharose (panel E) columns.

Previously we had shown that a His-tagged CcmI binds to the C terminus of apocytochrome c2 through its large periplasmic domain (19). We repeated the binding assays with the newly available FLAG-CcmI and Strep-apocytochrome c2 (Fig. 5E) and its mutant variants (supplemental Fig. S1B) to control that the different epitope tags (i.e. FLAG versus His tag) do not interfere with the CcmI-apocytochrome c2 interactions. The data confirmed that FLAG-CcmI and His-CcmI behaved similarly, recognizing mainly the C-terminal portion of apocytochrome c2 rather than its other structural elements.

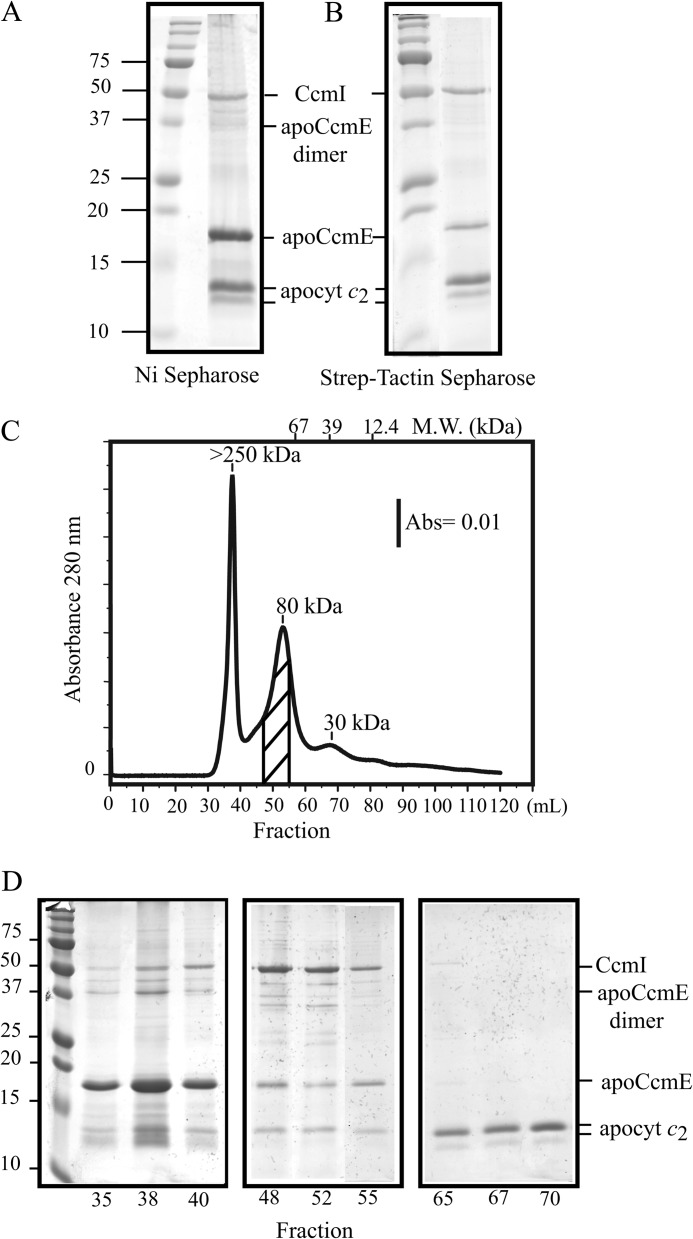

ApoCcmE Forms a Ternary Complex with CcmI and Apocytochrome c2

Binary interactions detected between apoCcmE-CcmI, apoCcmE-apocytochrome c2, and CcmI-apocytochrome c2 suggested that these proteins might form a stable ternary complex in vitro. Incubation mixtures containing His-apoCcmE, Strep-apocytochrome c2, and FLAG-CcmI altogether were loaded onto either Strep-Tactin- or Ni2+-Sepharose resin-containing columns. Co-purification assays showed that these three proteins co-eluted together (Fig. 6, A and B). Comparison of the amount of the ternary complexes formed by these three proteins (Fig. 6, A and B) with the corresponding appropriate binary complexes (Fig. 3, A and B, versus Fig. 5, D and E) further supported the finding that apoCcmE and CcmI do not compete directly with each other for the same structural elements of apocytochrome c2.

FIGURE 6.

ApoCcmE forms a ternary complex with CcmI and apocytochrome c2. A, co-purification of FLAG-CcmI and Strep-apocytochrome c2 with His-apoCcmE using Ni2+-Sepharose resin is shown. B, co-purification of FLAG-CcmI and His-apoCcmE with Strep-apocytochrome c2 using Strep-Tactin-Sepharose resin is shown. C, shown is an elution profile (absorbance at 280 nm as a function of the volume) of a mixture containing His-apoCcmE, FLAG-CcmI, and Strep-apocytochrome c2 from the Sephacryl S200 column in buffer containing 0.01% DDM. Estimation of the molecular masses (kDa) was done according to the calibration of the column using bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (39 kDa), and horse heart cytochrome c (12.4 kDa). Elution volume of the different standards and their respective molecular masses are depicted on the top of the chromatogram. The area of the chromatogram where FLAG-CcmI, His-apoCcmE, and Strep-apocytochrome c2 are co-eluted as a ternary complex is highlighted with diagonal lines. D, SDS-PAGE profiles of selected fractions are shown. Fractions 35–40 (left panel) and 65–70 (right panel) contain mainly aggregates of apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2, respectively, and fractions 48, 52, and 55 contain the quasi-stoichiometric ternary complex composed of FLAG-CcmI, His-apoCcmE, and Strep-apocytochrome c2, as indicated on the right. Note that proteins with higher molecular masses (e. i., CcmI) stained more intensely with Coomassie Blue as compared with smaller proteins (i.e. apoCcmE and apocytochrome c2).

Size exclusion chromatography was used to confirm the formation of the ternary complex of apoCcmE, CcmI, and apocytochrome c2. After incubation of the three proteins under the standard assay conditions, the mixture was loaded onto a previously calibrated Sephacryl-S200 column. The elution profile was monitored at 280 nm, and selected elution fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6, C and D). The bulk of apoCcmE was found in the first peak eluted at the column dead volume corresponding to a molecular mass larger than 250 kDa, where CcmI and apocytochrome c2 were also present, albeit at lower amounts (Fig. 6D, fractions 35–40). This observation suggested that the three proteins formed a multisubunit complex(es) containing large amounts of apoCcmE. The next peak covering a range of 110 to 65 kDa (Fig. 6D, fractions 48–55) contained CcmI, apoCcmE, and apocytochrome c2 (roughly at stoichiometric ratios, considering molecular masses of 50, 18, and 13.5 kDa for CcmI, apoCcmE, and apocytochrome c2, respectively). Finally, fractions 65–70 contained mainly excess apocytochrome c2 not retained by apoCcmE or CcmI. Overall data, therefore, further supported the formation in vitro of a ternary complex composed of apoCcmE, CcmI, and apocytochrome c2.

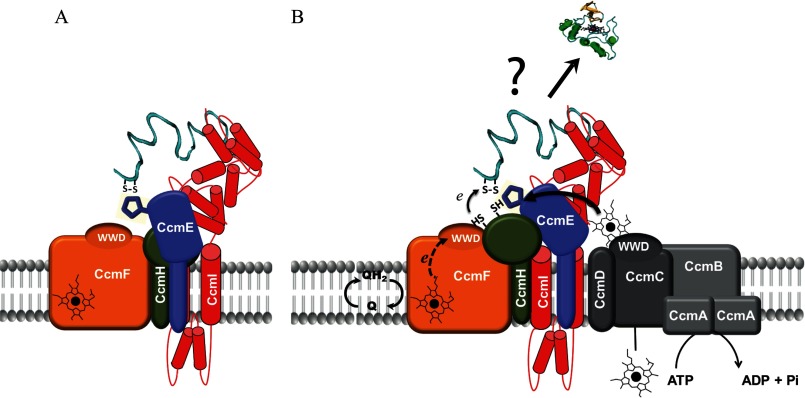

ApoCcmE Interacts Directly with the CcmI and CcmH Components of the Heme Ligation Complex CcmFHI in R. capsulatus Membranes

In light of the stable ternary complex observed in vitro between apocytochrome c2, apoCcmE, and CcmI, we examined the interactions of these proteins with the heme ligation core complex CcmFHI of R. capsulatus. Co-purification assays were conducted using 500 μg of DDM-solubilized membranes from an R. capsulatus strain overproducing the CcmFHI complex (MTSRP1.r1/pNJ2, Table 1) supplemented with purified His-apoCcmE or His-CcmI under the assay conditions used in vitro with purified proteins. The interacting partners were identified by immunoblot analysis of the elution fractions from the Ni2+-Sepharose columns. Upon incubation of the solubilized membranes with purified His-apoCcmE, we observed that mainly the CcmI and CcmH, but not CcmF, co-purified with His-apoCcmE (Fig. 7A, lane 3). Similarly, when purified His-CcmI was used, co-purification of CcmF and CcmH with His-CcmI was observed as seen earlier (7) (Fig. 7B, lane 3). In addition, the anti-apoCcmE antibodies recognized in the elution fraction a band of 18 kDa, reminiscent of the size of native CcmE. This suggested that CcmE might interact directly with the CcmFHI complex (Fig. 7B, lane 3). Initially, unambiguous identification of CcmE in R. capsulatus solubilized membranes was challenging as the available anti-apoCcmE polyclonal antibodies identifies multiple bands with apparent molecular masses of 37, 30, 28, 27, and 18 kDa (Fig. 7B, lane 1). However, based on the CcmE amino acid sequence, the use of a CcmE knock-out strain (MD2, Table 1) and R. capsulatus His-apoCcmE protein produced and purified from E. coli membranes (Fig. 2, B and C), we attributed the ∼ 18- and ∼37-kDa bands to R. capsulatus CcmE and its dimeric form, respectively. The intense band with a molecular weight of 28 kDa, detected in solubilized membranes of R. capsulatus wild type (MT1131, Table 1) and CcmE knock out strains (data not shown), was considered to be a nonspecifically recognized protein, and the bands located between the 25 and 37-kDa molecular mass markers were attributed to peroxidase activity-containing proteins like the c-type cytochromes (note that R. capsulatus has several membrane-bound c-type cytochromes) detected with the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate. The latter bands were absent when the anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate was used as the secondary antibody (data not shown). The data, therefore, indicated convincingly that apoCcmE is associated with the heme ligation complex in a manner independent of the presence of heme. We, therefore, concluded that CcmE together with CcmF, CcmH, and CcmI form a multisubunit maturation complex that recognizes apocytochrome c2.

FIGURE 7.

ApoCcmE forms a multisubunit complex with the heme ligation components CcmI and CcmH in R. capsulatus membranes. A, shown is an immunoblot analysis of the elution fraction obtained using DDM-dispersed R. capsulatus membranes incubated with purified His-apoCcmE and loaded onto a Ni2+-Sepharose column. Lane 1, ∼30 μg of the protein mixture after incubation and before loading onto the column (BC); lane 2, elution fraction of a control experiment performed just with R. capsulatus membranes shows that none of the proteins of interest is retained unspecifically by the Ni2+-Sepharose resin (Mb); lane 3, an elution fraction shows that CcmI and CcmH, but not CcmF, are co-purified together with His-apoCcmE under the conditions used (Mb + apoCcmE). B, shown is an immunoblot analysis of the elution fractions obtained using DDM-dispersed R. capsulatus membranes incubated with purified His-CcmI and loaded onto a Ni2+-Sepharose column. Lane 1 is as in panel A; lane 2 is as in panel A; lane 3, the elution fraction shows that CcmF, CcmH, and native CcmE are co-purified together with His-CcmI (Mb + CcmI). Note that CcmE detection shows several bands (marked with a ×) between the 25- and 37-kDa marker that are either unspecifically recognized by the antibodies or are heme-dependent peroxidase activity exhibiting c-type cytochromes due to the detection system. The band corresponding specifically to CcmE co-purifying with His-CcmI is seen at 18 kDa.

DISCUSSION

Earlier studies using co-immunoprecipitation assays and native gel electrophoresis documented physical interactions between the Ccm components, showing that they form various multisubunit complexes (e.g. CcmABCD, CcmCDE, CcmFHI (7, 29–31)). Similarly, direct interactions between the appropriate Ccm components and the apocytochrome substrates were also reported. For example, genetic approaches, like the yeast two hybrid screens, revealed that in Arabidopsis thaliana CcmFN2 and CcmH interacted with apocytochrome c (32, 33). E. coli CcmH could reduce the disulfide bond of a apocytochrome c–like peptide in vitro (16), and R. capsulatus Cys-less CcmG could co-purify with apocytochrome c2 (34). Previously, we showed that the large periplasmic domain of CcmI with its TPR motifs interacted strongly with the C terminus of R. capsulatus apocytochrome c2, whereas its membrane integral domain was needed for the integrity of the CcmFHI complex (19). In this work we extended these protein-protein interactions studies to other Ccm components. In particular, we inquired whether, and if so how, the heme chaperone apoCcmE recognizes the apocytochromes c substrates and the heme ligation complex CcmFHI.

First, we found that, like CcmI, apoCcmE interacted directly with the apo- and not with the holo-cytochrome c2 of R. capsulatus. However, unlike CcmI, the apoCcmE-apocytochrome c2 interactions involved the N-terminal, and not the C-terminal, portion of the apocytochrome. Moreover, these interactions were sensitive to ambient ionic strength and were stronger when a disulfide bond was present at the apocytochrome heme-binding site. Although no three-dimensional structure of an apocytochrome c is yet available, conceivably, R. capsulatus apocytochrome c2 might adopt different conformations according to the redox state of its C1XXC2H heme-binding site Cys residues. Besides forming disulfide bonds, the free thiols (or thiolates) of the Cys residues can also interact with nearby charged residues (35) and affect protein-protein interactions (36, 37). The three-dimensional structure of apoCcmE (8, 9) shows at the top of its β-barrel fold a surface-exposed region composed of hydrophobic and basic residues. This region is near the His residue that binds heme covalently and is thought to act as the heme platform. Assuming that this area may be a docking site for the apocytochrome c2 carrying a disulfide bond, reduction of this bond might alter the environment of the heme-binding site of apocytochrome c2 and consequently affect its interactions with apoCcmE.

In E. coli cells a cytochrome b562 derivative with a C1XXXH (R98C) binding motif forms a complex with heme and CcmE (18). The heme was covalently bound to the Cys-98 of this c-type cytochrome mimic and the His-130 of CcmE. This complex was observed in vitro using the purified H. thermophilus apocytochrome c552 but not the cytochrome b562 variant. Interestingly, before heme attachment, the apocytochrome b562 derivative is fully folded as a four-helical bundle, whereas the apocytochrome c552 forms a molten globule (18). In fact, H. thermophilus apocytochrome c552 is notorious in acquiring heme independently of the Ccm machinery in E. coli cytoplasm and also in vitro (38, 39). Thus, the global conformation of an apocytochrome is important for the Ccm process. With the exception of a few cases like H. thermophilus apocytochrome c552, Class-I apocytochromes are usually unfolded before heme binding and do not bind heme readily unless they are assisted by the Ccm machinery. Remarkably though, our data indicate that, like CcmI, apoCcmE can recognize and bind to apocytochrome in the absence of its covalently bound heme. Whether similar interactions also occur with holoCcmE awaits the purification of R. capsulatus holoCcmE.

Second, we found that purified apoCcmE (and its H123A mutant) also interact with purified CcmI, which is a subunit of the CcmFHI complex. Moreover, apoCcmE formed a stable ternary complex together with CcmI and apocytochrome c2. The high propensity for oligomerization shown by the members of the oligo-binding-fold family proteins like CcmE plus the highly hydrophobic nature of CcmI and apoCcmE precluded us from determining a precise subunit stoichiometry for the ternary complex. Nonetheless, the occurrence of this complex strongly suggested that apoCcmE interacted closely with the heme ligation complex CcmFHI. Indeed, the data obtained using DDM-dispersed R. capsulatus membranes indicated that CcmI and CcmH co-purified with apoCcmE. Similarly, CcmF, CcmH, and CcmE co-purified with CcmI, providing further evidence that apoCcmE interacted closely with the heme ligation components CcmFHI (Fig. 8A). However, considering that CcmF did not co-purify with apoCcmE, these two proteins might not interact directly within the CcmFHI complex, as suggested (15). Earlier co-immunoprecipitation data using anti-CcmF antibodies indicated that apoCcmE interacted with CcmF in E. coli, although the reciprocal experiments using anti-CcmE antibodies remained inconclusive (41). However, no protein-protein interaction(s) between CcmE and CcmH has been reported before this study. Furthermore, CcmI might be the component linking the heme ligation complex, the heme chaperone CcmE, and the apocytochrome c substrates altogether, as depicted in Fig. 8A, and inferred based on earlier genetic studies (40).

FIGURE 8.

Hypothetical models for apoCcmE interactions with an apocytochrome substrate and the CcmFHI heme ligation complex. A, the figure depicts apoCcmE interacting directly with apocytochrome c2 and the R. capsulatus heme ligation complex components CcmI and CcmH while interacting indirectly with CcmF. The model derives from the observations that apoCcmE forms a stable ternary complex with apocytochrome c and CcmI and co-purifies less readily with CcmF, inferring direct and indirect interactions, respectively. B, the figure depicts a putative large molecular entity composed of the CcmFHI-CcmE complex (as in panel A) associated with the heme translocation complex CcmABCD. If such a supercomplex exists, then conceivably the C-terminal portion of the unfolded apocytochrome c2 is captured via the periplasmic domain of CcmI of the CcmFHI core complex and interacts with apoCcmE to position its heme-binding site near CcmH so that heme-binding site disulfide bond reduction occurs if needed. When heme is translocated from the cytoplasm and becomes available at CcmC, then apoCcmE is converted to holoCcmE by interacting directly with CcmC and CcmD. After ATP hydrolysis by CcmA, holoCcmE becomes available to transfer heme to the apocytochrome c2, which remains trapped at the CcmFHI complex, with CcmF responsible for reduction of the heme iron in holoCcmE to facilitate heme ligation. It should be emphasized that the mechanism and order of the events described in panel B are hypothetical.

The finding that CcmI-apocytochrome c2-apoCcmE forms a stable ternary complex in vitro together with the data obtained using solubilized membranes raises the possibility of whether or not CcmABCD, CcmECcmFHI, and apocytochrome c form altogether a very large molecular complex (Fig. 8B). Earlier, co-localization of CcmF, CcmI, and CcmH in high molecular weight R. capsulatus membrane fractions (∼800 kDa) has been reported (7). Similarly, high molecular weight complexes containing CcmF and CcmH were also observed in A. thaliana (∼500 kDa) (32) and Triticum aestivum (∼700 kDa) (42). Excitingly, ongoing co-purification assays using similar R. capsulatus DDM-dispersed membranes indicate that all components of the heme ligation CcmFHI and the heme chaperone CcmE co-elute together when membranes are supplemented with exogenous apocytochrome c2. It now remains to be seen which one(s) of the remaining Ccm components is also located in these large molecular entities.

Finally, recognition of an apocytochrome c by the apoCcmE might appear counterintuitive at first, as only the holoCcmE would be suitable for the Ccm process. However, provided that a multisubunit maturation complex composed of CcmABCD-CcmE-CcmFHI exists in R. capsulatus membranes (Fig. 8B), one might wonder whether in the absence of heme apoCcmE associates more tightly with CcmFHI than CcmABCD. If so, once apocytochrome c is trapped by CcmI of the CcmFHI complex, then apoCcmE would assist apocytochrome to position correctly for reduction of the disulfide bond at its heme-binding site, possibly via CcmH. According to this hypothesis, only when CcmC is ready to load heme into apoCcmE will stable CcmE-CcmCD complex be formed (31). And only upon ATP hydrolysis by the CcmAB complex (43, 44) will the holoCcmE thus formed be released to transfer heme to the apocytochrome c trapped by CcmFHI (45) (Fig. 8B). Future experiments undoubtedly will further address these issues.

In summary, this study established that apoCcmE interacts directly not only with an apocytochrome substrate but also with the CcmH and CcmI components of the heme ligation complex CcmFHI. Clearly, these interactions occur in the absence and possibly in the presence of apocytochrome c2 and heme. These findings now provide important insights into the process of how CcmE recognizes the apocytochrome c substrates together with the CcmFHI complex for heme ligation during the maturation of the c-type cytochromes.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 38237 (to F. D.). This work was also supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy through Grant DE-FG02–91ER20052 for the production, purification, and assay of the proteins and their mutant variants (to F. D.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Fig. S1.

- Ccm

- cytochrome c maturation

- DDM

- n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bowman S. E., Bren K. L. (2008) The chemistry and biochemistry of heme c. Functional bases for covalent attachment. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25, 1118–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertini I., Cavallaro G., Rosato A. (2006) Cytochrome c. Occurrence and functions. Chem. Rev. 106, 90–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanders C., Turkarslan S., Lee D. W., Daldal F. (2010) Cytochrome c biogenesis. The Ccm system. Trends Microbiol. 18, 266–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stevens J. M., Mavridou D. A., Hamer R., Kritsiligkou P., Goddard A. D., Ferguson S. J. (2011) Cytochrome c biogenesis System I. FEBS J. 278, 4170–4178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thöny-Meyer L. (2003) A heme chaperone for cytochrome c biosynthesis. Biochemistry 42, 13099–13105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee D., Pervushin K., Bischof D., Braun M., Thöny-Meyer L. (2005) Unusual heme-histidine bond in the active site of a chaperone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3716–3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanders C., Turkarslan S., Lee D. W., Onder O., Kranz R. G., Daldal F. (2008) The cytochrome c maturation components CcmF, CcmH, and CcmI form a membrane-integral multisubunit heme ligation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29715–29722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnesano F., Banci L., Barker P. D., Bertini I., Rosato A., Su X. C., Viezzoli M. S. (2002) Solution structure and characterization of the heme chaperone CcmE. Biochemistry 41, 13587–13594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enggist E., Thöny-Meyer L., Güntert P., Pervushin K. (2002) NMR structure of the heme chaperone CcmE reveals a novel functional motif. Structure 10, 1551–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arcus V. (2002) OB-fold domains. A snapshot of the evolution of sequence, structure, and function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richard-Fogal C. L., Frawley E. R., Bonner E. R., Zhu H., San Francisco B., Kranz R. G. (2009) A conserved haem redox and trafficking pathway for cofactor attachment. EMBO J. 28, 2349–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahuja U., Thöny-Meyer L. (2003) Dynamic features of a heme delivery system for cytochrome c maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52061–52070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ren Q., Thony-Meyer L. (2001) Physical interaction of CcmC with heme and the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32591–32596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee J. H., Harvat E. M., Stevens J. M., Ferguson S. J., Saier M. H., Jr. (2007) Evolutionary origins of members of a superfamily of integral membrane cytochrome c biogenesis proteins. Biochim.Biophys. Acta 1768, 2164–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. San Francisco B., Bretsnyder E. C., Rodgers K. R., Kranz R. G. (2011) Heme ligand identification and redox properties of the cytochrome c synthetase, CcmF. Biochemistry 50, 10974–10985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Matteo A., Gianni S., Schininà M. E., Giorgi A., Altieri F., Calosci N., Brunori M., Travaglini-Allocatelli C. (2007) A strategic protein in cytochrome c maturation. Three-dimensional structure of CcmH and binding to apocytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27012–27019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanders C., Boulay C., Daldal F. (2007) Membrane-spanning and periplasmic segments of CcmI have distinct functions during cytochrome c biogenesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 189, 789–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mavridou D. A., Stevens J. M., Mönkemeyer L., Daltrop O., di Gleria K., Kessler B. M., Ferguson S. J., Allen J. W. (2012) A pivotal heme-transfer reaction intermediate in cytochrome c biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2342–2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verissimo A. F., Yang H., Wu X., Sanders C., Daldal F. (2011) CcmI subunit of CcmFHI heme ligation complex functions as an apocytochrome c chaperone during c-type cytochrome maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40452–40463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daldal F., Cheng S., Applebaum J., Davidson E., Prince R. C. (1986) Cytochrome c(2) is not essential for photosynthetic growth of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 2012–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring harbor Laboratory Press, NY [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas P. E., Ryan D., Levin W. (1976) An improved staining procedure for the detection of the peroxidase activity of cytochrome P-450 on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 75, 168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulz H., Thöny-Meyer L. (2000) Interspecies complementation of Escherichia coli ccm mutants. CcmE (CycJ) from Bradyrhizobium japonicum acts as a heme chaperone during cytochrome c maturation. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6831–6833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holden H. M., Meyer T. E., Cusanovich M. A., Daldal F., Rayment I. (1987) Crystallization and preliminary analysis of crystals of cytochrome c2 from Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Mol. Biol. 195, 229–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ambler R. P. (1991) Sequence variability in bacterial cytochromes c. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1058, 42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benning M. M., Wesenberg G., Caffrey M. S., Bartsch R. G., Meyer T. E., Cusanovich M. A., Rayment I., Holden H. M. (1991) Molecular structure of cytochrome c2 isolated from Rhodobacter capsulatus determined at 2.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 220, 673–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hasegawa J., Yoshida T., Yamazaki T., Sambongi Y., Yu Y., Igarashi Y., Kodama T., Yamazaki K., Kyogoku Y., Kobayashi Y. (1998) Solution structure of thermostable cytochrome c552 from Hydrogenobacter thermophilus determined by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37, 9641–9649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldman B. S., Beckman D. L., Bali A., Monika E. M., Gabbert K. K., Kranz R. G. (1997) Molecular and immunological analysis of an ABC transporter complex required for cytochrome c biogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 724–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ahuja U., Thöny-Meyer L. (2005) CcmD is involved in complex formation between CcmC and the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Richard-Fogal C., Kranz R. G. (2010) The CcmC·heme·CcmE complex in heme trafficking and cytochrome c biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 350–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meyer E. H., Giegé P., Gelhaye E., Rayapuram N., Ahuja U., Thöny-Meyer L., Grienenberger J. M., Bonnard G. (2005) AtCCMH, an essential component of the c-type cytochrome maturation pathway in Arabidopsis mitochondria, interacts with apocytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16113–16118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rayapuram N., Hagenmuller J., Grienenberger J. M., Bonnard G., Giegé P. (2008) The three mitochondrial encoded CcmF proteins form a complex that interacts with CCMH and c-type apocytochromes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25200–25208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turkarslan S., Sanders C., Ekici S., Daldal F. (2008) Compensatory thio-redox interactions between DsbA, CcdA and CcmG unveil the apocytochrome c holdase role of CcmG during cytochrome c maturation. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 652–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roos G., Foloppe N., Messens J. (2013) Understanding the pK (a) of redox cysteines. The key role of hydrogen bonding. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 94–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marino S. M., Gladyshev V. N. (2010) Cysteine function governs its conservation and degeneration and restricts its utilization on protein surfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 902–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marino S. M., Gladyshev V. N. (2012) Analysis and functional prediction of reactive cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4419–4425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Daltrop O., Allen J. W., Willis A. C., Ferguson S. J. (2002) In vitro formation of a c-type cytochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7872–7876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sambongi Y., Uchiyama S., Kobayashi Y., Igarashi Y., Hasegawa J. (2002) Cytochrome c from a thermophilic bacterium has provided insights into the mechanisms of protein maturation, folding, and stability. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 3355–3361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sanders C., Deshmukh M., Astor D., Kranz R. G., Daldal F. (2005) Overproduction of CcmG and CcmFH(Rc) fully suppresses the c-type cytochrome biogenesis defect of Rhodobacter capsulatus CcmI-null mutants. J. Bacteriol. 187, 4245–4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ren Q., Ahuja U., Thöny-Meyer L. (2002) A bacterial cytochrome c heme lyase. CcmF forms a complex with the heme chaperone CcmE and CcmH but not with apocytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7657–7663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Giegé P., Rayapuram N., Meyer E. H., Grienenberger J. M., Bonnard G. (2004) CcmF(C) involved in cytochrome c maturation is present in a large sized complex in wheat mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 563, 165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Feissner R. E., Richard-Fogal C. L., Frawley E. R., Kranz R. G. (2006) ABC transporter-mediated release of a haem chaperone allows cytochrome c biogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Richard-Fogal C. L., Frawley E. R., Kranz R. G. (2008) Topology and function of CcmD in cytochrome c maturation. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3489–3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Christensen O., Harvat E. M., Thöny-Meyer L., Ferguson S. J., Stevens J. M. (2007) Loss of ATP hydrolysis activity by CcmAB results in loss of c-type cytochrome synthesis and incomplete processing of CcmE. FEBS J 274, 2322–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deshmukh M., May M., Zhang Y., Gabbert K. K., Karberg K. A., Kranz R. G., Daldal F. (2002) Overexpression of ccl1–2 can bypass the need for the putative apocytochrome chaperone CycH during the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 1069–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lang S. E., Jenney F. E., Jr., Daldal F. (1996) Rhodobacter capsulatus CycH. A bipartite gene product with pleiotropic effects on the biogenesis of structurally different c-type cytochromes. J. Bacteriol. 178, 5279–5290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Deshmukh M., Brasseur G., Daldal F. (2000) Novel Rhodobacter capsulatus genes required for the biogenesis of various c-type cytochromes. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bhagwat A. S., Sohail A., Roberts R. J. (1986) Cloning and characterization of the dcm locus of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 166, 751–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Keen N. T., Tamaki S., Kobayashi D., Trollinger D. (1988) Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.