Background: αSyn is central to Parkinsonism, but its native state is unsettled.

Results: A new, facile method for cross-linking αSyn in living cells, including neurons, reveals a major 60-kDa form consistent with a tetramer. Cell lysis destabilizes it, yielding mostly monomers.

Conclusion: αSyn exists principally as a metastable tetramer in vivo.

Significance: Models of native αSyn as an unfolded monomer should be reconsidered.

Keywords: α-Synuclein, Erythrocyte, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Neurons, Parkinson Disease, β-Synuclein, Cross-linking, Oligomers

Abstract

Aggregation of α-synuclein (αSyn) in neurons produces the hallmark cytopathology of Parkinson disease and related synucleinopathies. Since its discovery, αSyn has been thought to exist normally in cells as an unfolded monomer. We recently reported that αSyn can instead exist in cells as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation and binds lipid vesicles more avidly than unfolded recombinant monomers (Bartels, T., Choi, J. G., and Selkoe, D. J. (2011) Nature 477, 107–110). However, a subsequent study again concluded that cellular αSyn is an unfolded monomer (Fauvet, B., Mbefo, M. K., Fares, M. B., Desobry, C., Michael, S., Ardah, M. T., Tsika, E., Coune, P., Prudent, M., Lion, N., Eliezer, D., Moore, D. J., Schneider, B., Aebischer, P., El-Agnaf, O. M., Masliah, E., and Lashuel, H. A. (2012) J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15345–15364). Here we describe a simple in vivo cross-linking method that reveals a major ∼60-kDa form of endogenous αSyn (monomer, 14.5 kDa) in intact cells and smaller amounts of ∼80- and ∼100-kDa forms with the same isoelectric point as the 60-kDa species. Controls indicate that the apparent 60-kDa tetramer exists normally and does not arise from pathological aggregation. The pattern of a major 60-kDa and minor 80- and 100-kDa species plus variable amounts of free monomers occurs endogenously in primary neurons and erythroid cells as well as neuroblastoma cells overexpressing αSyn. A similar pattern occurs for the homologue, β-synuclein, which does not undergo pathogenic aggregation. Cell lysis destabilizes the apparent 60-kDa tetramer, leaving mostly free monomers and some 80-kDa oligomer. However, lysis at high protein concentrations allows partial recovery of the 60-kDa tetramer. Together with our prior findings, these data suggest that endogenous αSyn exists principally as a 60-kDa tetramer in living cells but is lysis-sensitive, making the study of natural αSyn challenging outside of intact cells.

Introduction

Since its discovery as the first causative gene product for Parkinson disease (3) and the major constituent of Lewy bodies (4), α-synuclein (αSyn)2 has been increasingly implicated as a key pathogenic protein in both sporadic and familial forms of the disorder. αSyn has long been thought to occur normally as a natively unfolded monomer of ∼14.5 kDa (5). Accordingly, recombinant and cell-derived αSyn has often been studied using denaturing methods, as it was believed to be unstructured already. In contrast to these assumptions, our laboratory recently used a range of methods to observe that αSyn can be found in untransfected neuroblastoma cells and other cell lines and in human erythrocytes in apparent tetrameric assemblies that, upon purification under non-denaturing conditions, were found to contain substantial α-helical structure (1). An independent report at the same time described a protocol to recover bacterially expressed αSyn as a helically folded tetramer and provided an NMR structure supporting this model (6). A third laboratory has also reported evidence that bacterially expressed αSyn can form helically folded oligomers depending on the purification method (7), and a fourth has successfully reproduced our purification of folded, oligomeric αSyn from erythrocytes (8).

Nevertheless, these new findings have been controversial. For example, a recent paper reported experiments that suggested to the authors that αSyn existed almost exclusively as unfolded monomers in various cell lines or after purification from erythrocytes (2). Since we published our original findings (1), we have conducted extensive experiments to better delineate the assembly state of native αSyn in cells. We recognized that most of the methods we had used to identify native αSyn tetramers, including sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation, scanning transmission electron microscopy, and native gel electrophoresis (1), are not facile and thus are difficult for investigators to apply to the rapid analysis of the assembly state of αSyn in cells and tissue. The lack of an easy, consistent method to observe native αSyn oligomers in cells has made it challenging to obtain clarity about their existence and properties.

We have now developed a simple and reproducible method employing in vivo cross-linking that readily enables us to detect the apparent assembly state of αSyn in intact cells. Using this method and employing extensive controls, we show here that the major form of endogenous αSyn in several different cell types, including primary neurons, is an oligomer of ∼60 kDa consistent with the size of a tetramer. The method also traps smaller amounts of αSyn species migrating at ∼80 and ∼100 kDa on SDS-PAGE that have the same isoelectric point as the 60-kDa putative tetramer and may thus be conformationally distinct homo-oligomers. Surprisingly, standard lysis of the cells followed by the same cross-linking protocol applied in vitro yields predominantly free monomers plus some of the 80-kDa oligomer, with marked destabilization of the 60-kDa apparent tetramer. However, if the lysis protocol is modified to maintain high protein concentrations, the 60-kDa tetramer is preserved in a concentration-dependent manner. These and additional findings herein are consistent with the existence of metastable oligomers that principally size as tetramers in intact, normal cells, in accord with the model proposed by Bartels et al. (1) and Wang et al. (6). Our findings have important implications for properly studying endogenous, native αSyn inside and outside of intact cells, and for modeling αSyn misfolding and pathogenic assembly in brain disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

2F12, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to αSyn, was generated by immunizing αSyn−/− (KO) mice with αSyn purified as described (1) from human erythrocytes. 2F12 hybridoma supernatants were used at 1:2 to 1:10 for immunoblotting; after subsequent affinity purification, the antibody was used at 0.2–3.6 μg/ml. Additional αSyn mAbs were 15G7 (9), Syn1 (BD Biosciences), LB509 (Santa Cruz), and 211 (Santa Cruz); in addition, the polyclonal antibody (pAb) C20 (Santa Cruz) was used. Other antibodies were: mAb EP1537Y to β-synuclein (Novus Biologicals), pAb anti-DJ-1 (10), mAb H68.4 to Transferrin receptor (Invitrogen), pAb anti-synaptobrevin 2 (Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany), mAb BRM-22 to HSP-70 (Sigma), mAb 71.1 to GAPDH (Sigma), polyclonal anti-voltage-dependent ion channel (PA1–954A, Affinity Bioreagents), mAb DLP1 to DRP-1 (BD Biosciences), mAb M2 to the FLAG tag (Sigma), mAb AA2 to β-tubulin (Sigma), pAb A-14 to the c-myc tag (sc-789, Santa Cruz), pAb to hen egg lysozyme (PA1-21476, Thermo Scientific), pAb to Ran (4462, Cell Signaling), mAb to the V5 tag (R960–25, Invitrogen), mAb PRK8 to Parkin (Santa Cruz), mAb anti-calmodulin (05–173, Millipore), pAb anti-14–3-3 (pan) (ab9063, Abcam), and pAb anti-UCH-L1 (ab1761, Millipore). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies to mouse, rabbit, and rat IgG were from GE Healthcare.

cDNA Cloning

The deletion construct αSynΔ71–82 was generated from a pcDNA3.1 plasmid containing full-length human αSyn using the QuikChange II mutagenesis kit (Agilent) with the 5′-oligonucleotide primers 5′-TTGGAGGAGCAGTGGAGGGAGCAGGGAG-3′ and 5′-CTCCCTGCTCCCTCCACTGCTCCTCCAA-3′ following the manufacturer's instructions. Constructs pcDNA4/αSyn, pcDNA4/αSyn-FLAG3, pcDNA4/αSyn-V5, and pcDNA4/αSyn-mycHis were generated using the forward primer 5′-GCGCGATATCCTGCAGATGGATGTATTCATGGAAAGG-3′ and the reverse primers 5′-GGGTATCAAGACTACGAACCTGAAGCCTGATCTAGACTCGAGC-3′, 5′-GCTCGAGTCTAGATCACGTAGAATCGAGACCGAGGAGAGGGTTAGGGATAGGCTTACCTTCGAAGGGCCCTCTGGCTTCAGGTTCGTAGTCTTGATACCC-3′, 5′-GCGCTCTAGATCACTTGTCATCGTCATCCTTGTAATCGATATCATGATCTTTATAATCACCGTCATGGTCTTTGTAGTCGGCTTCAGGTTCGTAGTCTTG-3′, and 5′-GGGTATCAAGACTACGAACCTGAAGCCTCTAGACTCGAGC-3′, respectively. Cloning into pcDNA4/TO/myc-His A (Invitrogen) was carried out using PstI and XbaI restriction sites. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

αSyn Cell Lines and Transfection

All materials were purchased from Invitrogen unless stated otherwise. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Human erythroid leukemia cells (HEL; ATCC number TIB-180) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (ATCC modification) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 10 units/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin at densities from 0.2 to 1.5 × 106 cells/ml. Human neuroblastoma cells (BE(2)-M17, called M17D; ATCC number CRL-2267) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 units/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mm l-glutamine. M17D cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's directions. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

Primary neurons were cultured from E18 Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). Rats were euthanized with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Embryonic cortices were isolated and dissociated with trypsin and trituration. Cells were plated in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 10 units/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine at 680 cells/mm2 on BioCoat poly-d-lysine-coated culture dishes (BD Biosciences). After 4 h, medium was changed to Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27, 2 mm GlutaMAX, and 100 μg/ml gentamicin. Half of the medium was replaced every 4 days; on the first medium change, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (Sigma) and uridine (Sigma) were added to concentrations of 100 and 500 μg/μl, respectively, to inhibit glial cell growth.

Cross-linking

Disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG), disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS), dithiobis(succinimidyl) propionate (DSP) and 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DFDNB) were purchased from Thermo Scientific. Cross-linkers were stored at 4 °C with desiccant. Cells were collected by trituration (HEL and M17D) or scraping (primary rat neurons), washed once with PBS, and resuspended in PBS with 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture, EDTA-free (Roche Applied Science). Immediately before use, cross-linkers were prepared at 50× final concentration in DMSO. Samples were incubated with cross-linker for 30 min at 37 °C with rotation unless stated otherwise. The reaction was quenched with the addition of 1 m Tris, pH 7.6, to 50 mm final concentration and incubated for 15 min at RT. After quenching, in vivo cross-linked samples were lysed by a 15 s sonication (Sonic Dismembrator model 300, Fisher, using a microtip at a setting of 40) then ultracentrifuged 30 min at 213,000 × g unless stated otherwise. For in vitro cross-linking, the cells were first lysed by a 15 s sonication and then either cross-linked directly and ultracentrifuged (crude) or else ultracentrifuged before cross-linking just the supernatant (pure cytosol). To generate total protein lysates (that also contain membrane proteins), the detergent Triton X-100 (TX-100) was added after cell lysis at a final concentration of 1% (v/v) followed by 10 min of incubation on ice and centrifugation.

Immunoprecipitation, Gel Electrophoresis, and Immunoblotting

All materials were purchased from Invitrogen unless stated otherwise. Total protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's directions. Samples were prepared for electrophoresis by dilution with the respective lysis buffer, the addition of 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer, and boiling for 10 min. If not stated otherwise, 30 μg of total protein were loaded per lane. Immunoprecipitation was carried out by incubating 3–5 μg/μl (protein concentration) cytosolic lysates with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 3 h followed by 3 brief washes with PBS/protease inhibitor (PI), and boiling in 1× sample buffer. An equivalent to 300–500% of the starting material was loaded. Samples were electrophoresed on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels with NuPAGE MES-SDS running buffer and the SeeBlue Plus2 molecular weight marker. After electrophoresis, gels were electroblotted onto Immobilon-P 0.45-μm or Immobilon-PSQ 0.2-μm PVDF membranes (Millipore) for 1 h at 400 mA constant current at 4 °C in 25 mm Tris, 192 mm glycine, 20% methanol transfer buffer. After transfer, membranes were incubated in 0.4% paraformaldehyde, PBS for 30 min at RT (11), rinsed twice with PBS, stained with 0.1% Ponceau S in 5% acetic acid, rinsed with water, and blocked in 5% nonfat milk in PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBS-T) for either 30 min at RT or overnight at 4 °C. After blocking, membranes were incubated in primary antibody in 5% milk in PBS-T with 0.02% sodium azide for either 1 h at RT or overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then washed 3 times for 10 min in 1% milk in PBS-T at RT and incubated in secondary antibody in 1% milk in PBS-T for 45 min at RT. Membranes were then washed 3 times for 10 min in PBS-T and developed with ECL Plus or ECL Prime (GE Healthcare-Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequential Protein Extraction

After treatment with DSG or else DMSO (vehicle) alone in PBS/PI without TX-100, cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 435,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected (PBS cytosolic fraction). The pellet was resolubilized in PBS/PI with 1% TX-100 and again centrifuged at 435,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was collected (TX fraction: membrane proteins), and the pellet was boiled in 1× NuPAGE sample buffer containing 2% lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS fraction: LDS-soluble proteins).

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

All materials were purchased from Invitrogen unless stated otherwise. Samples were first electrophoresed under non-denaturing conditions on Novex pH 3–7 isoelectric focusing gels, fixed according to manufacturer's recommendations, Coomassie-stained (GelCode Blue, Thermo Scientific), and prepared for SDS-PAGE according to the manufacturer's directions. The isoelectric focusing lanes were then loaded onto NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris gels with two-dimensional wells, electrophoresed, and blotted as above. Incompletely cross-linked samples were used for two-dimensional gel analyses as this strongly reduced the background of WB signals and made the detection of cross-linking intermediates as well as endproducts possible. Incomplete in vivo cross-linking was achieved by incubating the cross-linking reaction at 4 °C.

Preparation and Cross-linking of Recombinant αSyn

Recombinant αSyn (wt αSyn) was prepared, purified, and desalted as described (12). Pure recombinant αSyn was cross-linked in vitro at a concentration of 10 ng/μl in PBS/PI using a range of DSG concentrations. As a control, pure egg lysozyme (MP Biomedicals) was cross-linked under identical conditions. For in vivo cross-linking, bacteria were pelleted, washed, cross-linked, quenched, and lysed analogously to mammalian cells using a range of DSG concentrations.

RESULTS

Cross-linking of Intact Cells Reveals Endogenous αSyn in Distinct Higher Molecular Weight Species with a Size Range of 60–100 kDa

To assess the physiological assembly states of αSyn in a natural cellular environment, i.e. in the cytoplasm of intact cells, we sought both the least invasive method and a readily cultured cell line with substantial endogenous expression of human αSyn. Primary neurons are an attractive system in which to study an abundant neuronal protein like αSyn, but variations in primary cultures and the fragility and limited quantity of these cells make the extensive biochemical optimization of a new protocol difficult. Immortalized cells are more available and easily handled, but even lines of neuronal origin such as SK-N-MC or M17D human neuroblastoma cells have low endogenous αSyn expression compared with primary neurons (Fig. 1A), making detection difficult and raising questions about the physiological relevance of potential findings. Common solutions for the detection problem such as overexpressing αSyn were avoided here whenever possible, as the natural steady-state condition of αSyn in such cells might be altered. Fresh erythrocytes, an abundant source of endogenous αSyn (13, 14), express high levels of hemoglobin that can interfere with αSyn detection by immunoblotting due to similar gel migration. We reasoned that if erythrocytes are rich in αSyn, their progenitor cells may also be, and we thus identified the human erythroleukemia cell line HEL (15) as our initial system for development of a cross-linking protocol. HEL cells combine certain advantages of immortal cells and primary neurons; they are easy to culture and express abundant endogenous human α-synuclein (Fig. 1A) but have very low levels of hemoglobin (not shown).

FIGURE 1.

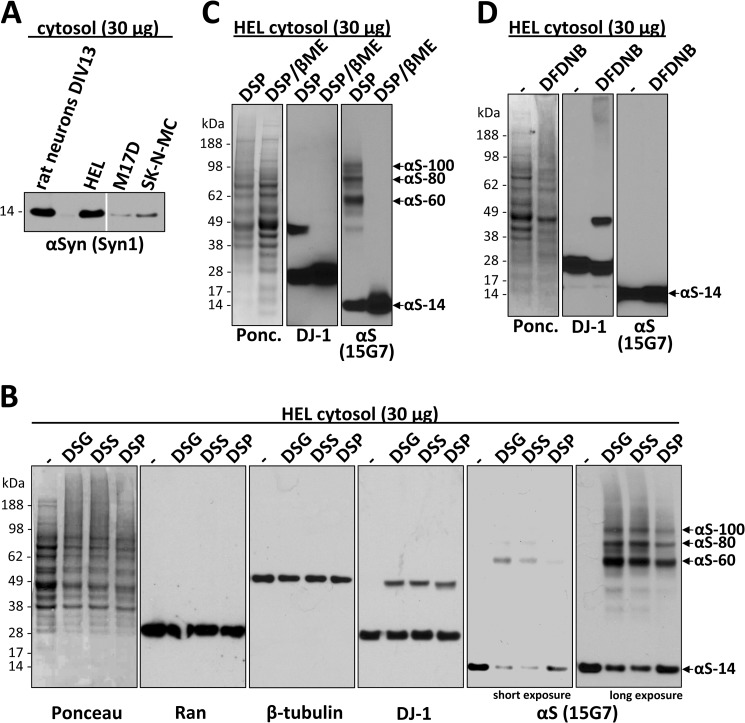

HEL cells express high levels of endogenous αSyn that can be specifically cross-linked in vivo as a major ∼60-kDa species and minor species that include ∼80 and ∼100 kDa. A, cytosols (post-20,000 × g) from HEL cells, rat primary cortical neurons (DIV13), and M17D and SK-N-MC human neuroblastoma cells were immunoblotted with the αSyn mAb Syn1. Identical exposures of the same blot are shown; film was cut at the white line. B, HEL cells underwent in vivo cross-linking using the cell-permeant amine-reactive cross-linkers DSG, DSS, and DSP (each at 1 mm). Control cells (−) were treated with DMSO vehicle alone. Cytosols were generated by lysing cells via sonication for 15 s in PBS/PI and centrifuging at 20,000 × g. As controls for cross-linking efficiency, blots were stained with Ponceau solution or a rabbit pAb (10) to the dimeric cytosolic protein DJ-1. As negative controls, the monomeric GTPase Ran as well as β-tubulin were detected using specific antibodies. αSyn was detected using rat mAb 15G7; short and long exposures of the same blot are shown. C, HEL cells were subjected to in vivo cross-linking with the cleavable cross-linker DSP (1 mm), and cytosols were prepared (post-20,000 × g). For lanes labeled DSP/βME (β-mercaptoethanol), the DSP cross-linker was cleaved after cross-linking by boiling in sample buffer with 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, whereas lanes labeled DSP were boiled in sample buffer alone. General cross-linking efficiency was visualized by Ponceau (Ponc.) staining and by blotting for DJ-1. D, HEL cells underwent in vivo cross-linking using the short spacer length cross-linker DFDNB (1 mm) versus DMSO alone (−), and 20,000 × g cytosols were prepared. Ponceau staining and blotting for DJ-1 verified the general efficiency of the cross-linker.

Regarding possible methods to assess αSyn assembly state in vivo, we considered a FRET/fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy approach that has been used to detect interactions of αSyn molecules in intact cells (16). However, this requires exogenous expression of tagged αSyn, raising concerns about any aggregation induced by overexpressing and/or modifying the protein. Also, the method cannot define the size of oligomers exhibiting FRET. An alternative approach is to trap native assemblies through the in vivo cross-linking of endogenous, unlabeled αSyn with small, cell-permeant cross-linkers. Therefore, to define the assembly state of native αSyn in living HEL cells, we screened several membrane-permeable cross-linkers with differing spacer lengths. We initially tested the amine-reactive DSS (spacer length 11.4 Å) used in our earlier study (1) and the additional amine-reactive cross-linkers DSG (7.7 Å) and DSP (12.0 Å). All 3 compounds were initially tried at a concentration of 1 mm per the manufacturer's recommendations, and the effectiveness of the cross-linking was analyzed by immunoblotting. The expected shift of a portion of cellular proteins toward the higher Mr range, as visualized by Ponceau staining of PVDF blots (Fig. 1B, first panel), and the successful cross-linking of a portion of endogenous DJ-1 in its known dimeric form (17–19) (Fig. 1B, fourth panel) confirmed the general effectiveness of the three cross-linkers in the HEL cells. Negative controls to rule out nonspecific cross-linking of cellular monomeric proteins into artificial oligomers by our protocol included endogenous Ran and β-tubulin, each of which remained monomeric after applying the DSG protocol to the same HEL cells (Fig. 1B; second and third panel). The αSyn mAb 15G7 (9) detected a predominant ∼60-kDa species and a corresponding decrease in the levels of free monomer after in vivo (intact cell) application of each of the three cross-linkers compared with vehicle alone (Fig. 1B, fifth and sixth panels), consistent with our previous αSyn cross-linking results using DSS (1). The invariant observation of this endogenous ∼60-kDa species by in vivo cross-linking throughout the current study is consistent with the existence of tetrameric α-synuclein in cells (1, 6); αSyn purified from human erythrocytes had previously been sized at 57.8 kDa by sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation (mass of the cellular N-acetylated monomer = 14,502 daltons (1)). Longer exposure of the blot revealed additional αSyn immunoreactive species of ∼80 and ∼100 kDa in size (Fig. 1B, sixth panel) that were less abundant than the 60-kDa species. This pattern of three principal mid-Mr αSyn bands accompanied by decreased levels of free monomers upon in vivo cross-linking was confirmed by blotting with several different αSyn antibodies (Fig. 2A and see below). The specificity of the cross-linking was further supported by the fact that the three species (designated αS-60, αS-80, and αS-100 hereafter) reverted to monomer (αS-14) upon β-mercaptoethanol-induced cleavage of the reducible cross-linker DSP (Fig. 1C, right panel), just as occurred with the known DJ-1 dimer in the same cells (Fig. 1C, middle panel). Interestingly, the short spacer length (3.0 Å), amine-reactive cross-linker DFDNB was unable to trap the αS-60, -80, and -100 species (Fig. 1D, right panel), although its general ability to cross-link some cellular proteins was shown by Ponceau-staining of the blot (Fig. 1D, left panel) and partial trapping of the endogenous DJ-1 dimer (Fig. 1D, middle panel). This negative result with DFDNB suggests a defined molecular structure (i.e. a particular spacing of the reactive amine groups) in the cross-linked αSyn assemblies, further supporting the specificity of the results. Because DSG appeared to be the most efficient of the three cross-linkers in these initial experiments as judged by the relative αSyn oligomer-to-free-monomer ratio (Fig. 1B, fifth and sixth panels), we used DSG in subsequent experiments.

FIGURE 2.

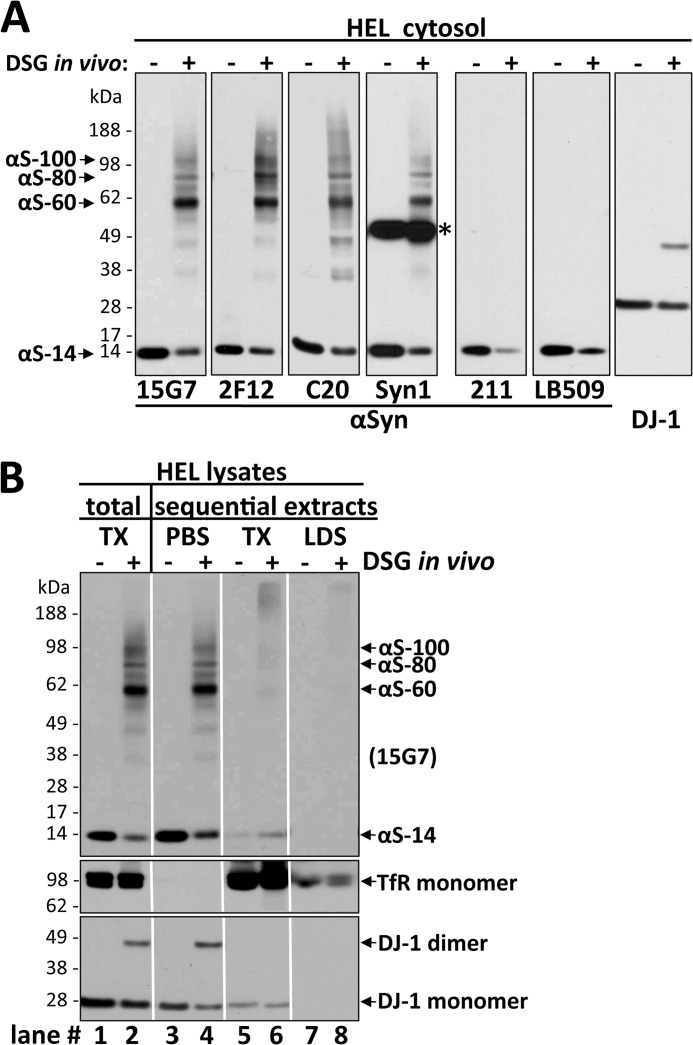

Multiple αSyn antibodies confirm the specificity of the ∼60-, ∼80-, and ∼100-kDa species, all of which are enriched in the high speed cytosol fraction. A, HEL cells were treated in vivo with DMSO alone (−) or 1 mm DSG (+), sonicated in PBS/PI, and spun at 435,000 × g for 30 min. The resultant cytosols were blotted with αSyn antibodies 15G7, 2F12, C20, Syn1, 211, or LB509 and with DJ-1 antibody (10) as a control for cross-linking efficiency. Note that all six αSyn antibodies revealed lower levels of free monomer (14 kDa) after cross-linking. See “Results” for details. The asterisk marks a crossreactive band detected by the Syn1 antibody. B, shown are TX-100 total lysates and sequential extracts of HEL cells treated in vivo with DMSO (−) or 1 mm DSG (+). Total lysates (left panel) were generated by bringing cells lysed by sonication in PBS/PI to 1% TX-100 (TX) followed by 10 min incubation on ice and ultracentrifugation (435,000 × g, 30 min). For sequential extractions (right three panels), see “Experimental Procedures” and “Results.” Enrichment of soluble proteins in the PBS cytosol was confirmed by strong signals for the cytosolic protein DJ-1 (monomer and dimer) and the absence of transferrin receptor (TfR). The TX-100 fractions showed the opposite pattern, consistent with enrichment of membrane proteins. mAb 15G7 revealed co-fractionation of all αSyn species with DJ-1 in the cytosol; only minor αSyn amounts were detected in the TX and LDS fractions. Identical exposures of the same blot are shown; film was cut at the white lines.

We found that cross-linking the cells at the physiological temperature of 37 °C was substantially more efficient than at room temperature (supplemental Fig. S1A; note the ratios of putative oligomers to free monomer). Applying a DSG concentration of 1 mm to the cells routinely allowed good visualization of the cross-linked endogenous αSyn species, and these were more pronounced at 2 mm with less free monomers (supplemental Fig. S1B, right panel). DSG at 5 mm resulted in a marked decrease or loss of all αSyn bands and mid-to-high Mr smearing and/or gel-excluded αSyn immunoreactivity (supplemental Fig. S1B, right panel), indicating the occurrence of nonspecific over-cross-linking. In contrast, DJ-1 behaved differently, as a DSG concentration of 5 mm allowed ∼90% of the protein to be trapped in its native dimeric state (supplemental Fig. S 1B, middle panel), with nonspecific high Mr smears only appearing at concentrations >5 mm (not shown). However, the cross-linking behavior of αSyn was not unique, as we observed a general loss of focused protein bands and an increase in high Mr smears and gel-excluded material on Ponceau-stained membranes when cross-linker concentrations were >1 mm (supplemental Fig. S1B, left panel). In further optimization experiments, cross-linking was most efficient when the volume of the cross-linking solution was 10–20-fold higher than the volume of the cell pellet; a ratio of 4 × 106 HEL cells in 200 μl of 1 mm DSG in PBS + PI mixture incubated at 37 °C for 30 min consistently led to the detection of high amounts of αS-60, -80, and -100 and accordingly low levels of free monomer (see, e.g. supplemental Fig. S1C, right panel, second lane).

Lee and Kamitani (11) recently described the use of 0.4% paraformaldehyde treatment of blots to enhance the immunodetection of αSyn monomers. We found that such treatment of membranes after transfer was important to allow quantitatively meaningful results with cross-linking, as αSyn monomers, but not the cross-linked 60–100-kDa species, were otherwise largely lost during the process of Western blot development (supplemental Fig. S1C). Without paraformaldehyde treatment of the blots, the relative level of apparent oligomers was overestimated due to the greater susceptibility of αSyn monomers to wash off the membrane during development (11). Thus, only when blots were paraformaldehyde-treated did the combined immunoreactivities of all αSyn species post-cross-linking approximate the amount of monomer alone pre-cross-linking. Approximating this “conservation of immunochemical matter” was a goal of the optimization of our cross-linking protocol and was achieved in virtually all figures herein.

In Vivo Cross-linking Reveals a Cytosolic 60-kDa Species as the Predominant αSyn Form in Intact Cells

To establish the specificity of the αSyn bands we detected and to better estimate their cellular levels, we examined a variety of anti-αSyn antibodies on HEL cells treated with 1 mm DSG versus vehicle alone using the optimized protocol described in the previous section (Fig. 2A). The well characterized antibodies Syn1, C20, and 15G7 as well as our newly generated mAb 2F12 confirmed that the 14-, 60-, 80-, and 100-kDa bands all contained αSyn. However, C20 showed relatively decreased sensitivity for the cross-linked species versus the monomer and stronger “smears” (although αS-60 was still the major species). 2F12 or 15G7 did not exhibit preferential reactivity for any of the species and thus were considered suitable to assess the relative levels of the different cellular αSyn species. Although both these antibodies led to similar results throughout this study, 15G7 was preferred, as it had been fully characterized before (9) and had slightly less background (Fig. 2A). In addition, Syn1 reacted similarly to 15G7 (and 2F12), but it showed the known strongly cross-reactive, nonspecific band at ∼50 kDa (20). Two other widely used αSyn antibodies, LB509 and 211, detected the decrease in free monomer levels upon cross-linking but failed to detect the cross-linked putative oligomers (Fig. 2A), likely due to inaccessibility of their epitopes caused by this cross-linker.

αSyn is generally believed to be predominantly cytosolic, with a small portion being membrane-associated (21, 22). To further characterize the subcellular distribution of the apparent αSyn oligomers in intact cells, we performed sequential extractions of whole HEL cell lysates after in vivo cross-linking. We found the αS-60, -80, and -100 kDa species to be present almost exclusively in the PBS-soluble extract (cytosol), which was devoid of the transmembrane protein transferrin receptor (TfR) and enriched in the cytosolic protein DJ-1 (Fig. 2B). To rule out the possibility that the αSyn species might be associated with remaining (small) vesicles or membrane fragments in the PBS cytosol, we applied a very high ultracentrifugation force of 435,000 × g. Comparison of this very high speed PBS cytosol with total protein extracts made by lysing the cells in PBS, 1% Triton X-100 (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 1 and 2 to lanes 3 and 4) showed no differences in the relative levels of the four principal αSyn bands, indicating that all species of αSyn detected were overwhelmingly cytosolic. In accord, membrane fractions prepared in the absence or presence of cross-linker (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6) contained only small amounts of principally monomeric αSyn. Finally, the subsequent centrifugal fraction soluble in 2% LDS (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 8) contained small amounts of high Mr αSyn near the top of the gel, which may correspond to large, LDS-soluble αSyn aggregates in the cells and/or nonspecifically cross-linked αSyn molecules. Taken together, all of the findings thus far suggest that a principal form of endogenous αSyn in intact HEL cells is a soluble, cytosolic species that migrates at the size of a tetramer (60 kDa) after in vivo cross-linking. In addition, smaller amounts of cytosolic 80- and 100-kDa cross-linked species and free monomers (14 kDa) are detected.

60-, 80-, and 100-kDa-cross-linked αSyn Species Are Homo-oligomers

The results obtained so far are consistent with the recent recognition that αSyn can exist in part in homo-oligomeric, particularly tetrameric, forms (1, 6, 7). However, the very low abundance of bands that could be interpreted as oligomeric intermediates such as dimers or trimers upon cross-linking raised the alternative interpretation that the 60-kDa band could be a synuclein monomer-bound to an unknown ∼45–50-kDa interactor or to multiple smaller interactors, i.e. a hetero-oligomer. We reasoned that such a prominent and consistent interactor that is cross-linked to αSyn in all of our in vivo cross-linking experiments in different cell types (see below) would likely be one that had already been described in the extensive literature on αSyn over the last 20 years. Although there is a long list of single reports of αSyn-interacting proteins, most of them have not been confirmed independently. Nevertheless, we examined a virtually complete list of published αSyn interactors for their possible presence in the mid-Mr αSyn bands (especially the major αS-60 species) and were able to rule out all of these candidates for a variety of specific biochemical reasons (explained in supplemental Table S1 and its legend). Most importantly, for the cross-linked αS-60, -80, or -100 cytosolic species, we found no support for the presence of the most widely accepted interactors: Synphilin-1 (Ref. 23; size >200 kDa), HSP-70 (Ref. 24; see Fig. 5A), synaptobrevin-2 (Ref. 25; not expressed in HEL cells; see Fig. 6A); β-tubulin (Ref. 26; see Fig. 2A), or Parkin (Ref. 27; see Fig. 6A).

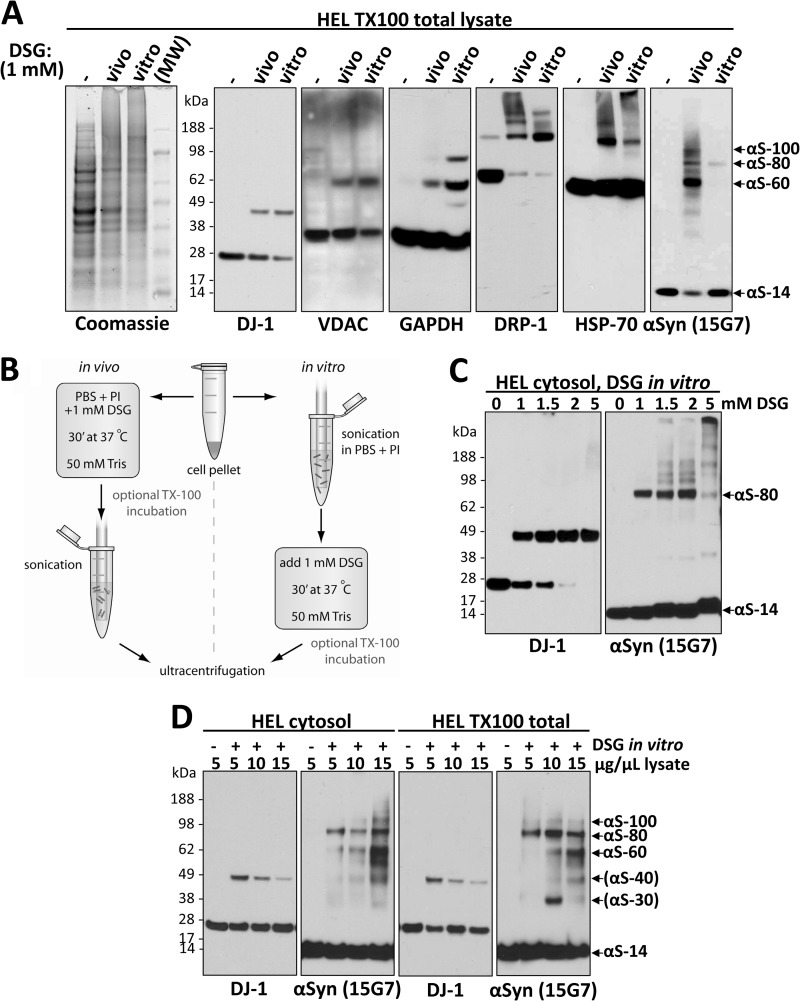

FIGURE 5.

The interactions of αSyn revealed by in vivo cross-linking are sensitive to cell lysis. A, αS-80, but not αS-60 or αS-100, is relatively resistant to cell lysis. The occurrence of in vivo and in vitro protein cross-linking was confirmed by Coomassie-staining of SDS-PAGE gels (far left panel) as well as for αSyn (mAb 15G7) and certain other normally oligomeric proteins by blotting with the indicated antibodies: DRP-1, dynamin-related protein 1; HSP-70, heat shock 70 kDa protein; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channel protein. HEL TX-100 total lysates (spun at 213,000 × g) were analyzed. Mr, molecular weight marker (SeeBlue Plus2). B, a schematic is shown of in vivo and in vitro cross-linking protocols (see “Experimental Procedures” and “Results” for details). C, increasing DSG concentration does not overcome the inability to trap αSyn species other than αS-80 in vitro. 4 × 106 HEL cells in 200 μl PBS/PI were lysed by sonication, treated with 1, 1.5, 2, or 5 mm DSG and spun at 213,000 × g. D, in vitro cross-linking in lysates of high protein concentration partially recovers the in vivo αSyn cross-linking pattern by stabilizing αS-60. Concentrated (15 μg/μl) lysates were generated by lysing HEL cells in small volumes of either PBS/PI (two panels on the left) or PBS/PI/1% TX-100 (two panels on the right) followed by centrifugation at 213,000 × g; decreasing concentrations were generated by diluting this 15 μg/μl sample. After cross-linking at the indicated protein concentrations, all samples were normalized to 5 μg/μl, and equal volumes were loaded. Of note, oligomerization intermediates, the putative dimer αS-30, and the putative trimer αS-40 could be detected in some of the sample to variable degrees.

FIGURE 6.

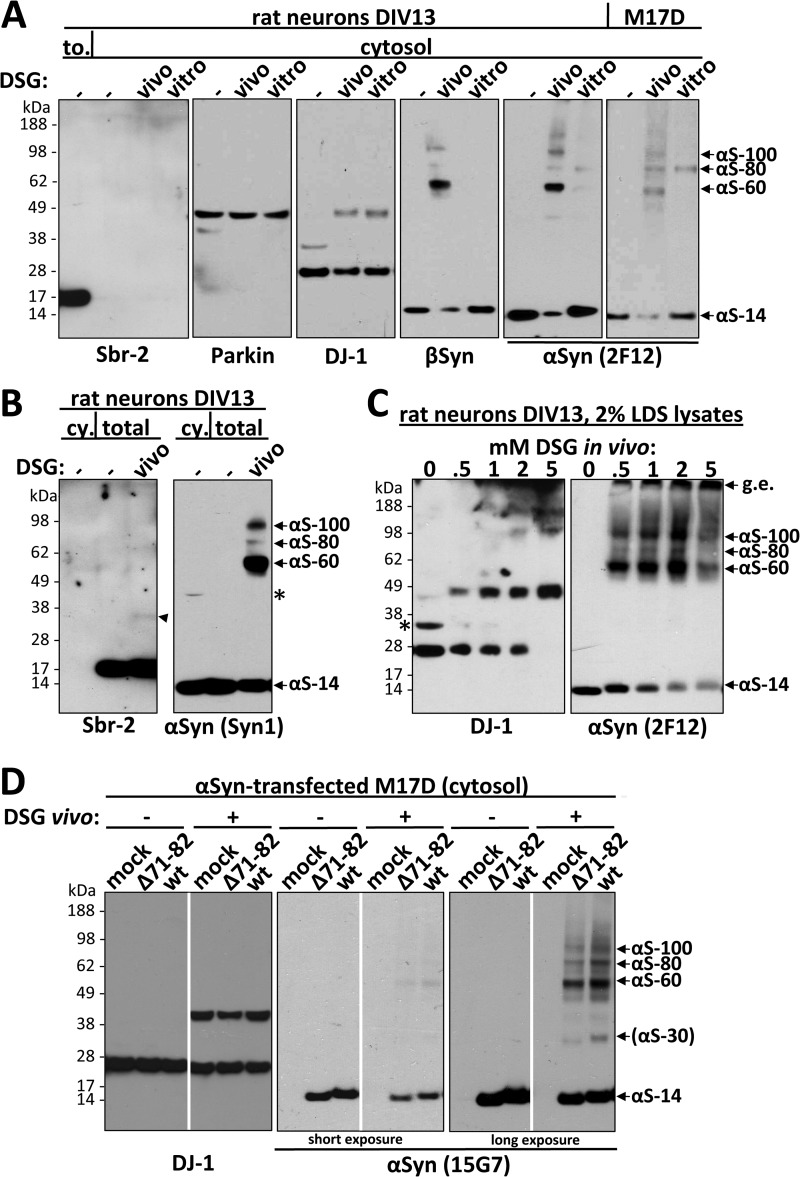

Cross-linking of endogenous α- and β-synuclein in primary neurons and endogenous and transfected αSyn in M17D cells validates the findings in HEL cells. A, shown is an immunoblot analysis of cytosols (213,000g) after DSG cross-linking of rat neurons and M17D cells. Primary cortical rat neurons (DIV13) were cross-linked in vivo or in vitro just as with HEL cells. pAb to Sbr-2 (left panel) detected a strong signal in a total protein lysate (to.) but not in cytosols. Blotting for DJ-1 confirmed the equal efficiency of in vivo and in vitro cross-linking. pAb EP1537Y was used to probe for βSyn, and mAb 2F12 was used for αSyn. B, shown is an immunoblot analysis of 1% TX-100 total lysates (213,000 × g) after in vivo DSG cross-linking of primary cortical rat neurons (DIV13). For comparison, a cytosol (cy.) is shown. Unlike Sbr-2, which was absent in cytosol, αSyn was equally present in cytosolic (cy.) and TX-100 total lysates (total). A weak ∼35-kDa band (arrowhead) was detected for Sbr-2 after cross-linking. The asterisks marks the nonspecific band detected by the antibody (see also Fig. 2B). C, rat neurons (DIV13) were cross-linked with increasing concentrations of DSG (0–5 mm) and immediately lysed in 2% LDS sample buffer. The asterisk marks a presumably nonspecific band detected by the antibody in rat neuronal lysates; g.e., gel-excluded. D, Wt αSyn and the NAC-domain mutant Δ71–82 were transiently expressed in M17D cells for 48 h followed by in vivo cross-linking with DSG (right panels in each pair) or just DMSO (left panels in each pair). As a control, vector only was transfected (mock). DJ-1 was a control for cross-linking efficiency and equal loading (left panel). Identical exposures of the same blot are shown; film was cut at white lines.

To address this homo-oligomer question further, we searched for cross-linking conditions that led to some detection of putative dimer/trimer intermediates by Western blotting. We found that performing the in vivo cross-linking reactions at 4 °C significantly reduced the efficiency of the cross-linking, as expected, and led to more apparent monomer, less apparent αS-60 tetramer, and more αS-30 and αS-40 bands that we interpreted as αSyn dimers and trimers, respectively (Fig. 3C, bottom left panel, and data not shown). This observation could be attributable to partial (incomplete) cross-linking, not necessarily to the existence of significant levels of endogenous dimers/trimers of αSyn in intact cells. Importantly, we also routinely detected significant amounts of apparent ∼30-kDa dimers by our standard 37 °C cross-linking protocol when we overexpressed αSyn in the human neuroblastoma cell line, M17D, which has very low endogenous αSyn expression (Fig. 3A; see also Fig. 6D, right panel). This accentuation of dimers was especially the case when C-terminally tagged αSyn was overexpressed (Fig. 3D). Together, these results suggest that the efficient oligomerization of αSyn fully into tetramers may be regulated by limiting cellular factors and may depend on the presence of an unmodified C terminus.

FIGURE 3.

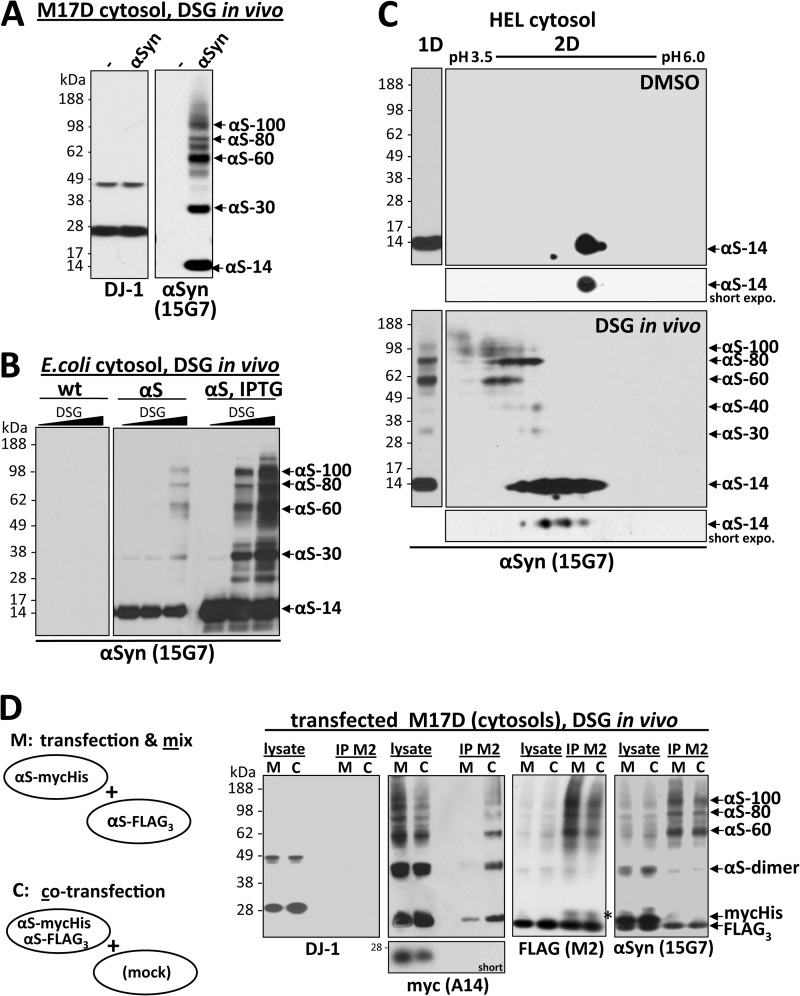

αSyn 60-, 80-, and 100-kDa cross-linked species are apparent homo-oligomers having different conformations or monomer numbers. A, wt αSyn was transiently expressed in the M17D neuroblastoma cell line for 48 h followed by in vivo cross-linking. As a control, mock-transfected cells (-) are shown. B, αSyn was expressed in E. coli BL21 cells (11) in the presence (right panel, right three lanes; strong expression) or absence (right panel, left three lanes; weaker background expression) of the inducer IPTG. As a control, lysates from wt E. coli BL21 are shown in the left panel. DSG concentrations of 0, 0.3, and 1 mm were applied to intact bacterial cells. IPTG, isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. C, incomplete in vivo cross-linking of αSyn was analyzed by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (one-dimensional (1D)) and two-dimensional gel-electrophoresis (2D). One-dimensional panels are on the left. SDS-PAGE/WB analysis is shown for cytosols from HEL cells DSG-cross-linked at 4 °C, resulting in an enhanced relative detection of monomers, putative αSyn dimers (αS-30), and trimers (αS-40). Two-dimensional panels on the right, control-treated as well as incompletely in vivo DSG-cross-linked HEL cell cytosols were run in a two-dimensional gel system. Proteins were separated by isoelectric focusing in the x axis at a pH range of 3.5–6.0 and in the y-axis by standard SDS-PAGE. In DMSO-treated samples (upper large panel and small panel showing a short exposure of the 14-kDa region), almost all αSyn focused at 14 kDa (y axis) and around its theoretical isoelectric point of pH 4.67 (x axis) as expected. Reaction of DSG with the αSyn species is expected to shift their isoelectric points to a more acidic position due to the masking of the positive charge of lysines. Therefore, in vivo DSG cross-linking (lower large panel and small panel show a short exposure of the 14-kDa region) yielded a 14-kDa spot at the position of unmodified monomers (compare with top panel) plus monomers at slightly more acidic positions (farther left), suggesting partial intramolecular modification of lysines in the monomer. A similar shift toward the lower pH range was observed for the αS-60, -80, and -100 species such that their isoelectric points aligned with the acid-shifted monomers. D, shown is the co-IP analysis of differently tagged αSyn molecules after co-expression and cross-linking. αSyn-mycHis and αSyn-FLAG3 were either expressed separately in two different cell populations and mixed just before in vivo cross-linking (M) or co-expressed in the same cell population and then mixed with mock-transfected cells just before in vivo cross-linking (C). After the in vivo cross-linking, lysates were subjected to FLAG-IP. Starting materials (lysate) and anti-FLAG IPs (IP M2) were analyzed by WB using specific antibodies for the myc-epitope (A14), the FLAG-epitope (M2), and αSyn (15G7). A short exposure of the monomer bands in the anti-myc blot demonstrates the relative depletion of monomers in comparison to the mid-Mr species shown in the long exposure of the blot. IP purity was confirmed by the absence of DJ-1 immunoreactivity (left panel) in the IP lanes. The asterisk marks IgG light chain bands.

The conclusion that the cells contain homo-oligomers of αSyn was further supported by applying our in vivo DSG cross-linking to Escherichia coli (BL21 strain) expressing human αSyn. In the complete absence of eukaryotic proteins, we still observed the αS-60, -80, and -100 species in the bacterial cytosols post cross-linking (Fig. 3B, right panels; the left panel shows wild-type (wt) bacteria as a negative control). Given the identical electrophoretic positions of the cross-linked species in αSyn-expressing bacteria and normal eukaryotic cells, the theoretical possibility of a bacterial protein forming the same putative hetero-oligomers with αSyn as occurs in mammalian cells is extremely unlikely. Our observation of trapping of αSyn oligomers in the bacterial cytosol is consistent with the recent reports of the purification of human αSyn tetramers from bacteria under certain non-denaturing conditions (6, 7). Of interest, the DSG trapping of the αS-60 tetramer at the expense of free monomer was less efficient in E. coli than in eukaryotic cells, and more αSyn was trapped at a dimer position (αS-30); this was especially true when the bacterial expression was markedly enhanced by IPTG induction (Fig. 3B, right panel).

To further assess the question of homo- versus hetero-oligomers of αSyn in intact cells, we performed two-dimensional gel analyses on cross-linked αSyn species from incompletely (4 °C) cross-linked Hel cells (Fig. 3C, large panels on the right; for comparison, representative one-dimensional gels are shown on the left). In the first dimension (x axis), proteins were separated by isoelectric point (isoelectric focusing), whereas the second dimension (y axis) was a standard SDS-PAGE separating proteins primarily by molecular weight. Immunoblot signals with identical isoelectric points on the x axis but different sizes on the y axis can be considered to be monomers and oligomers composed of the same protein. In non-cross-linked samples (Fig. 3C, large top right panel and short exposure below), the large majority of αSyn focused as a single spot at 14 kDa (y axis) and around its theoretical isoelectric point of pH 4.67 (x axis), as expected for the free monomer. The analysis of amine-cross-linked αSyn is complicated by the fact that the DSG modification of primary amines (lysines) in proteins shifts their isoelectric points to more acidic positions (a cysteine-based cross-linker, which would leave isoelectric points virtually unchanged, cannot be used with αSyn as it has no cysteines). Running the in vivo DSG-cross-linked samples on the two-dimensional gels yielded a 14-kDa spot at the expected pH ∼ 4.7 position of unmodified monomers plus some monomers shifted in the acidic direction, suggesting modification of lysine residues by the cross-linker and possibly some intramolecular cross-linking (Fig. 3C, large bottom right panel and short exposure below). For the αS-60, -80, and -100 in vivo cross-linked species, we observed a similar stepwise shift toward acidic pH as for the αS-14 monomer. Importantly, the αS-60, -80, and -100 species in the in vivo cross-linked sample shared their less acidic isoelectric points with the acid-shifted monomers and with faint αSyn species of ∼30 and ∼40 kDa representing probable dimers and trimers in these incompletely cross-linked samples. The observed array of fully and partially cross-linked 14-kDa and mid-Mr species with overlapping isoelectric points as well as the more completely cross-linked higher Mr species that are shifted in an acidic direction conforms to the results expected for homo-oligomeric proteins when one combines two-dimensional gels with amine-reactive cross-linking as here. Collectively, these two-dimensional gel results strongly suggest that the mid-Mr αSyn species detected by the in vivo cross-linking method are homo-multimers of αSyn. The presence of a heterologous protein(s) bound to αSyn in the αS-60, -80, and -100 species is highly unlikely, as this would be expected to shift their isoelectric points to different positions than that of the free monomer.

To obtain further evidence for homo-oligomers, i.e. more than one αSyn molecule in the mid-Mr bands, we next transiently co-expressed differentially tagged αSyn molecules (αS-FLAG3; αS-mycHis) either as pairs together in the same cells or, for negative control purposes, in separate cells that were later mixed together (Fig. 3D). At 48 h post-transfection, all cells were subjected to in vivo cross-linking, lysis, and an immunoprecipitation (IP) of their cytosols for the FLAG tag. The extent of any co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of the αSyn-mycHis proteins with the αS-FLAG3 was detected by immunoblotting for the myc-tag (Fig. 3D). As we hypothesized, only in the case of co-expression in the same cells did we detect significant co-IP of αSyn-mycHis with αS-FLAG3 in the putative oligomeric positions, indicating that the respective mid-Mr bands indeed represent oligomers that form inside intact cells and consist of differentially tagged αSyn proteins. A similar result was obtained by co-expressing αS-FLAG3 and αS-V5 (supplemental Fig. S2). Of interest, the in vivo cross-linking of these highly overexpressed and C-terminally tagged αSyn proteins led to more αSyn running as monomers that were decreased but not fully absent upon in vivo cross-linking and co-IP, suggesting the presence of some non-cross-linked αSyn oligomers in the lysates.

The 60-, 80-, and 100-kDa-cross-linked αSyn Species Are Homo-oligomers Distinct from the Products of “Diffusion-controlled” Cross-linking

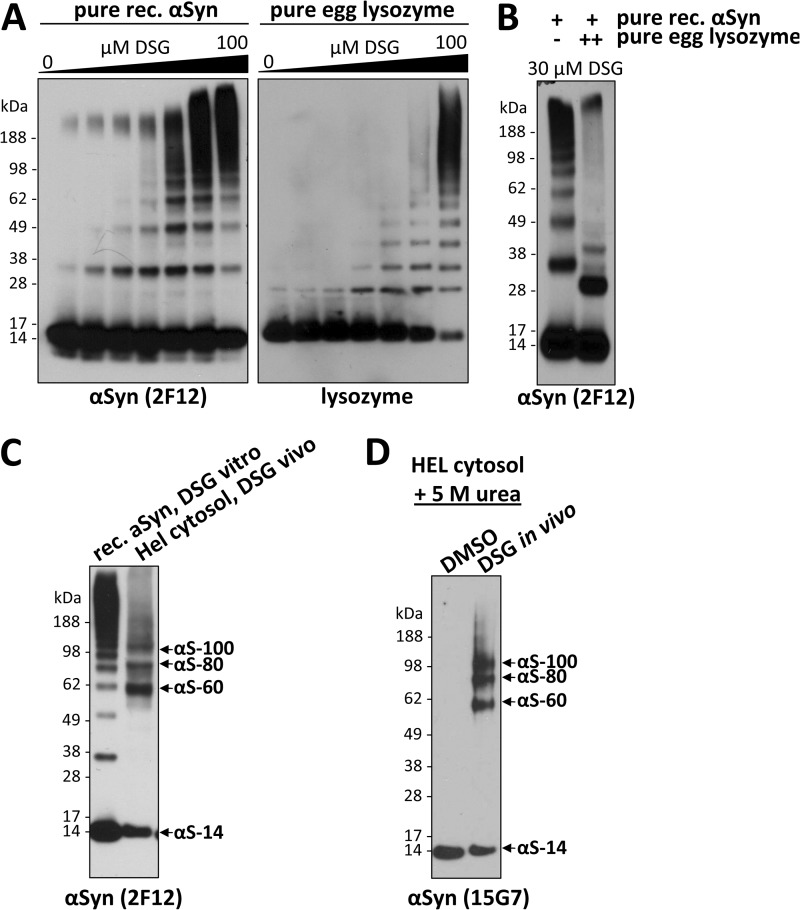

A recent study reported the detection of αSyn predominantly at a dimeric position after the application of cross-linker to intact cells (2), a finding that is not necessarily inconsistent with the findings we present above. Nevertheless, these authors interpreted their observed cross-linking as diffusion-controlled rather than the trapping of actual oligomers existing in the cells under physiological conditions. Yet a diffusion-controlled (nonspecific) association that would lead to abundant, well defined species running principally at the tetramer position with very small amounts of dimers (Figs. 1 and 2) appears improbable. First, if αSyn existed solely as monomers in the cytosol (2), then a truly diffusion-controlled mechanism should not favor the interaction of αSyn with other αSyn molecules but rather would cross-link αSyn to numerous different molecules it may randomly contact, which potentially comprises many cytosolic proteins; this would lead to a diffuse smear detectable by WB, not discrete bands. Second, the trapping of αSyn at defined dimeric positions (2) and even more so at mostly tetrameric positions (this study) seems an unlikely result for a nonspecific process. To assess what to expect from the diffusion-controlled (nonspecific) cross-linking of unfolded monomeric αSyn, as Fauvet et al. (2) proposed, we subjected recombinant αSyn that had been conventionally purified under denaturing conditions (12) to in vitro cross-linking using a gradient of DSG concentrations up to 100 μm; i.e. up to a cross-linker-to-αSyn ratio much higher than the 1 mm DSG we used in the cytoplasm of intact cells (Fig. 4A, left panel). We detected a ladder of cross-linker-induced αSyn oligomers that appeared to follow a stochastic process and whose pattern was DSG concentration-dependent. Cross-linker concentrations <30 μm trapped mostly monomers plus oligomer bands whose abundance decreased stepwise as their size increased, whereas 100 μm led to the detection of less oligomer bands and a large amount of αSyn smears in the high Mr range (Fig. 4A, left panel). By systematically varying the αSyn and DSG concentrations, we found that 30 μm DSG for a 10-ng/μl solution of pure αSyn was the best condition with regard to optimal trapping of low- and mid-Mr αSyn species. However, neither this purposefully optimized cross-linking ratio nor any other ratio we tried could generate an αSyn band pattern resembling that obtained with intact cell cross-linking, i.e. the prominent 60-kDa tetrameric band (this study) or even the abundant cellular dimers seen by Fauvet et al. (2). Moreover, applying an identical DSG gradient to a solution of the known monomeric protein lysozyme (purified from hen eggs) produced a closely similar, ladder-like pattern of oligomers (Fig. 4A, right panel), consistent with the conclusion that the pattern we see with pure αSyn in vitro is indeed the result of diffusion-controlled (random) events leading to the nonspecific cross-linking of a monomeric protein. Strikingly, adding only a 10-fold excess of pure lysozyme to our solution of pure recombinant αSyn before cross-linking led to αSyn-immunoreactive bands at altered positions that constitute hetero-oligomers of αSyn and lysozyme (Fig. 4B, right lane). This result suggests that the unfolded αSyn monomer does not favor in vitro interactions with other αSyn molecules over interactions with other random proteins it may contact. Based on this result, unfolded αSyn monomers in the cellular context might be expected to be cross-linked to other random proteins rather than preferentially to other αSyn molecules at defined positions, as we invariantly observed throughout the current study. Moreover, our cross-linking in intact cells leads to an oligomer pattern that is not remotely in agreement with the results of nonspecific (diffusion-controlled) cross-linking of free monomers, as established in Fig. 4A, left panel. We directly compared the results of the nonspecific cross-linking of pure, unfolded αSyn monomers at optimal DSG concentration (30 μm) to the cross-linking of endogenous αSyn in the cytosol of HEL cells (Fig. 4C). Obvious differences include (a) the virtual absence of intermediate dimers and trimers in the HEL cells, (b) the strong preference for the ∼60-kDa αSyn tetramer in HEL cells, although this position is not favored with nonspecific cross-linking in vitro, (c) the cellular tetramer migrating slightly faster than the pure tetramer generated by cross-linking the E. coli-expressed αSyn, suggesting that the former species sizes as a tetramer, but its precise manner of cross-linking may be slightly different from that of the analogous non-specifically cross-linked tetramer, and (d) the presence of the aS-80 and aS-100 species in the HEL cells that do not overlap with any of the products of the nonspecific cross-linking of pure unfolded monomers.

FIGURE 4.

αS-60, -80, and -100 are homo-oligomers distinct from the products of diffusion-controlled cross-linking. A, pure recombinant (rec.) αSyn and pure egg lysozyme were cross-linked at a concentration of 10 ng/μl using DSG concentrations of 0, 1, 3, 5, 10, 30, 100 μm, leading to an increasing detection of induced oligomers by WB using specific antibodies. Of note, the induced αSyn oligomers ran higher than the respective lysozyme oligomers, presumably due to a different structure of the cross-linked species. B, pure recombinant αSyn at a concentration of 10 ng/μl was cross-linked using 30 μm DSG in the presence (right panel) or absence (left panel) of a 10-fold molar excess of egg lysozyme. C, pure recombinant αSyn cross-linked at a concentration of 10 ng/μl using 30 μm DSG (left lane) was run on an SDS-PAGE next to a cytosol of HEL cells that had been subjected to standard DSG in vivo cross-linking. D, HEL cells were treated with DSG or just DMSO in vivo, and cytosols were prepared; these were then treated with 5 m urea (final concentration), boiled for 10 min, and run on SDS-PAGE.

Based on our extensive findings on the intracellular αSyn oligomers presented so far (e.g. two-dimensional gels, co-IP data, comparisons to cross-linking of pure monomers, ruling out of potential candidate interactors), the presence of heterologous protein(s) bound to αS-80 and -100 species is highly unlikely. Rather, these in vivo cross-linked species may differ from the predominant tetrameric αS-60 as to (a) the number of αSyn subunits (e.g. they are tetramers, hexamers, and octamers) or (b) different native conformations of the same-sized oligomer (e.g. the tetramer) that are thus trapped slightly differently by the DSG (i.e. they are conformers of each other). Regarding the latter possibility, we treated an in vivo cross-linked sample with a harsh denaturant (5 m urea) but still detected the same αSyn population of 60-, 80-, and 100-kDa bands (Fig. 4D), suggesting that if these are conformers, the DSG cross-linking precludes their subsequent denaturation by 5 m urea.

The in Vivo Interactions of Cellular αSyn Are Sensitive to Cell Lysis

Having examined αSyn species in intact cells by in vivo cross-linking, we next asked to what extent these species can also be cross-linked in cell lysates (in vitro). To this end we modified our in vivo cross-linking protocol in just one way; cell lysis occurred before rather than after cross-linking (Fig. 5B). All other parameters described earlier were left unchanged to enable meaningful comparison. The in vitro cross-linking was usually done on crude cell lysates (i.e. cross-linker was added immediately after cell lysis without centrifugation), but no major differences were observed if we first ultracentrifuged the lysates and cross-linked just the high speed cytosol. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels of vehicle-only and DSG treatments performed in vivo and in vitro confirmed the general efficiency of both cross-linking approaches, as indicated by a similar shift of many proteins to the higher Mr range (Fig. 5A, first panel). Importantly, several control proteins, DJ-1 (17–19), voltage-dependent ion channel (28, 29), GAPDH (30), Drp-1 (31), and HSP-70 (32), which are known to exist endogenously as oligomers in cells, could each be successfully cross-linked in their respective oligomeric states by both in vivo and in vitro cross-linking, although some modest protein-specific differences were observed (Fig. 5A, second to sixth panels). In striking contrast, cross-linking of αSyn in vivo versus in vitro revealed a major difference; the former trapped the now-familiar pattern of αS-60, -80, and -100 (and some very minor species) with low levels of monomers, whereas in vitro cross-linking led to the detection of mostly free monomers and a small amount of just the 80-kDa band (Fig. 5A, seventh panel). This observation is consistent with our finding that the efficient co-IP of differentially tagged αSyn species depended on cross-linking in vivo, whereas little interaction was detected without in vivo cross-linking (see Fig. 3D). Intriguingly, the ability to trap αS-80 by cross-linking in vitro was markedly decreased or abolished if the cell lysates were sonicated for 30 or 60 s (rather than our standard 15 s) before applying the DSG cross-linker (supplemental Fig. S3A, right panel), suggesting that the 80-kDa species is highly sensitive to the heat and/or shearing induced by sonication. DJ-1 analyzed simultaneously in the same cells behaved as expected; it was trapped in its endogenous dimeric state as efficiently by in vitro as by in vivo cross-linking, and sonication before in vitro cross-linking had no significant adverse effect (supplemental Fig. S3A, left panel). When we spiked recombinant human αSyn monomer into the HEL lysates before in vitro cross-linking, this pure, exogenous 14-kDa monomer specifically contributed to (i.e. augmented) the endogenous 80-kDa band, supportive of the interpretation that the endogenous αS-80 species is composed of just αSyn (supplemental Fig. S3B).

We consistently observed that the αS-60 species trapped by in vivo cross-linking was highly sensitive to cell lysis by various methods (e.g. liquid nitrogen with or without protease inhibitors; sonication) performed before in vitro cross-linking, whereas the αS-80 species persisted, albeit at substantially lower levels and accompanied by more free monomer than was observed in vivo (supplemental Fig. S3C). Raising the cross-linker concentration did not overcome the inability to recover αS-60 in vitro, i.e. we could detect only αS-80 and αS-14 by cross-linking after cell lysis (Fig. 5C). A possible explanation for this lability of the major in vivo species upon cell lysis in a standard buffer volume could be a dependence of the normal interactions of intracellular αSyn on high macromolecular concentrations. To test this hypothesis, we repeated the in vitro cross-linking approach after lysing the cells in small buffer volumes, i.e. at much higher protein concentrations, to better simulate the intracellular macromolecular crowding that obtains during in vivo cross-linking. Through a stepwise increase in protein concentration above the conventional 1–6 μg/μl in which cells were routinely lysed, we observed a striking concentration-dependent recovery of αS-60 in the more highly concentrated lysates whether this was done in PBS cytosols or in TX-100/PBS total lysates (Fig. 5D). Under these conditions, αS-60 became more abundant than the αS-80 that was the sole mid-Mr species recovered after in vitro cross-linking in conventional dilute buffer (Fig. 5D). Also, the pattern obtained by this in vitro cross-linking under protein crowding generally resembled that of in vivo cross-linking and looked nothing like the ladder of oligomers that pure αSyn formed under diffusion-controlled (nonspecific) cross-linking in vitro (Fig. 4A). In sharp contrast to the results with αSyn, higher protein concentrations led to decreased efficiency in trapping DJ-1 in its dimeric state, probably due to the decreased cross-linker-to-protein ratio. Even at the highest protein concentrations we could test, the αSyn pattern upon in vitro cross-linking was still somewhat different from that of in vivo cross-linking in that the lowered level of free monomers routinely seen in vivo (e.g. Fig. 5A, far right panel) could not be achieved in vitro (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that cellular αSyn exists in proteinaceous solution in assemblies requiring specific intermolecular interactions, with high macromolecule concentrations favoring the occurrence or stabilization of those interactions.

In Vivo Cross-linking of Primary Neurons Expressing α- and β-Synuclein Yields Closely Similar Putative Oligomers as Those in HEL Cells

To assess the relevance of the above findings on endogenous αSyn in HEL cells to endogenous αSyn in neurons, the target cells in human synucleinopathies, we analyzed primary rat neurons as well as the human neuroblastoma cell line, M17D. In agreement with earlier studies (33), rat primary neurons needed to be cultured for 7 days or longer to achieve substantial αSyn expression, which then was in the range of HEL cells (Fig. 1A). We routinely plated primary cortical rat neurons at high density (∼12 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish) and harvested them on day 13 in vitro (DIV13). Similar to the HEL cells, neurons treated with 1 mm DSG in vivo underwent the trapping of a major αS-60 and minor αS-80 and αS-100 species and a much lower level of free monomers in the cytosol (Fig. 6A, fifth panel). Just as in the HEL cells, the in vitro treatment of neuronal lysates with DSG led to the detection of only the αS-80 species and more free monomer (Fig. 6A, fifth panel). Immunoblotting for synaptobrevin-2 (Sbr-2) in a TX-100 total lysate confirmed the neuronal nature of the cells (Fig. 6A, first panel, first lane), whereas the absence of any Sbr-2 immunoreactivity in all the neuronal cytosol samples showed that the latter were devoid of membranes, as expected. The detection of DJ-1 dimers after in vivo and in vitro DSG cross-linking (Fig. 6A, third panel) once again confirmed the general effectiveness of both cross-linking protocols. We also probed the neurons for the known monomeric protein Parkin and observed only the monomer after either in vivo or in vitro cross-linking (Fig. 6A, second panel), again underscoring the lack of any evidence that the αSyn oligomers we detect are artificially induced by the cross-linking method. As in HEL cells, neuronal αSyn was similarly abundant in cytosol and TX-100 total lysates (Fig. 6B, second panel, compare first and second lanes). Sbr-2 was again exclusively found in total lysate, not cytosol (Fig. 6B, first panel). After in vivo cross-linking and lysis of the neurons in the presence of TX-100, we found a closely similar pattern of the αSyn mid-Mr species (Fig. 6B, second panel, third lane) as we saw in the cytosol (Fig. 6A, fifth panel). Here, all αSyn species could be cleanly detected by mAb Syn1, whose cross-reactive ∼50-kDa band was virtually absent in these DIV13 neurons. Blotting the in vivo cross-linked neuronal samples for Sbr-2 revealed its monomer and trace amounts of a 35-kDa band (arrowhead) that did not co-migrate with any of the cross-linked αSyn species (Fig. 6, A and B, first panels). This result rules against the possibility that a recently proposed interaction between αSyn and Sbr-2 (25) is responsible for our detection of the mid-Mr αSyn species; moreover, the latter occurs in the cytosol (Fig. 6A).

The human neuronal cell line M17D had low endogenous αSyn expression levels (Fig. 1A), but the findings from HEL cells and primary neurons, αS-60, -80, and -100 after in vivo cross-linking and just αS-80 after in vitro cross-linking, were again observed (Fig. 6A, sixth panel).

An advantage of the primary neurons over M17D and HEL cells was their significant endogenous expression of βSyn, enabling us to probe for any apparent oligomeric species of this partial homologue. In agreement with published data (33), we found βSyn monomer running slightly higher than αSyn monomer on SDS-PAGE despite the fact that βSyn is 6 residues shorter (134 versus 140 amino acids). This slightly higher gel migration as well as our inability to immunodetect any βSyn-reactive bands in lysates of M17D cells transiently overexpressing abundant αSyn (not shown) confirmed that our βSyn antibody does not detect αSyn. Using this specific antibody, a gel pattern strikingly reminiscent of that of αSyn was seen for endogenous βSyn in primary neurons undergoing DSG cross-linking; this is, a principal ∼60 kDa βSyn species with an associated decrease in monomer levels upon in vivo cross-linking and the sensitivity of this 60-kDa species to cell lysis when in vitro cross-linking was performed (Fig. 6A, fourth panel). In contrast to HEL and M17D cells, only a very weak 80-kDa αSyn band was detected in neurons (especially upon in vitro cross-linking), and the analogous βSyn band was barely detectable (Fig. 6A, compare the three right-most panels), suggesting that the putative oligomer patterns can vary subtly as a function of cell type and synuclein homolog. Because it is known that βSyn does not share the aggregation propensity of αSyn or play a pathogenic role in Parkinson disease (4, 34, 35), our closely similar in vivo and in vitro cross-linking data on βSyn and αSyn suggest that the αSyn oligomers we detect are neither the result of a pathological aggregation process nor induced by the cross-linker but rather occur normally in neurons.

In an attempt to better assess the relative abundance of the in vivo cross-linked αSyn species in primary neurons, we tested increasing concentrations of DSG from 0 to 5 mm (applied at our standard ratio of ∼4 × 106 cells per 200 μl of cross-linking solution). Also, in order not to miss any of the possible cellular αSyn species in this analysis, we lysed the cells after the in vivo cross-linking by boiling them directly in 2% LDS sample buffer, thus generating a total protein extract potentially also containing more insoluble species. We observed that increasing DSG concentrations led to a dose-dependent depletion of monomers but also to increasing amounts of gel-excluded αSyn immunoreactivity at higher DSG concentrations (Fig. 6C, right panel). This was in agreement with Ponceau staining of the blots, which showed a DSG dose-dependent increase in gel-excluded proteins in general (not shown) as well as with results obtained for DJ-1 (Fig. 6C, left panel). The highest degree of detection of the mid-Mr αSyn species (accompanied by low levels of free monomers) in neurons occurred at concentrations of 1–2 mm DSG (Fig. 6C, right panel), closely similar to what had been seen in HEL cells (compare with supplemental Fig. S1C). Thus, the data indicate that the 60-kDa putative tetramer is the prevalent endogenous αSyn species in primary cortical neurons.

To provide further evidence that the endogenous αSyn oligomers we detect are not due to pathogenic αSyn aggregation, we transiently expressed in M17D cells either wt human αSyn or an artificial αSyn mutant Δ71–82 that lacks a 12-amino acid stretch in the NAC domain shown to be required for αSyn aggregation in vitro (36) and performed an in vivo cross-linking analysis. For both wt and Δ71–82 αSyn, DSG treatment resulted in lower levels of the monomer and the usual 60 (major)-, 80-, and 100-kDa mid-Mr species (Fig. 6D, middle and right panels). This lack of difference in the in vivo pattern of Δ71–82 versus wt αSyn, like the analogous pattern seen for the (non-pathogenic) endogenous βSyn, supports the physiological (not pathological) nature of the putative oligomeric αSyn forms we invariably detect upon in vivo cross-linking of endogenous αSyn.

DISCUSSION

Here we systematically searched for endogenous assemblies of αSyn by applying cell-permeant cross-linkers to living cells. Using HEL cells that express high endogenous levels of αSyn as a new model system initially, we conducted extensive experiments to establish an optimized protocol based on the amine cross-linker DSG. We report that αSyn exists in intact cells, including HEL and primary cortical neurons, principally as mid-Mr species of ∼60, 80, and 100 kDa that can be detected by in vivo cross-linking, accompanied by low levels of free monomers. A 60-kDa αSyn species was the most abundant of the mid-Mr species and was the major form among all αSyn-immunoreactive species detected in living cells. These new data are consistent with recent reports that αSyn can exist as a physiological tetramer in cells (1, 6), as the combined molecular mass of four αSyn monomers (14,502 daltons each) adds up to 58 kDa. Like the solely monomeric αSyn observed without cross-linking, the mid-Mr αSyn species detected after in vivo cross-linking are recovered almost exclusively in the high speed cytosol during subcellular fractionation. The nearly equal isoelectric points of these DSG-cross-linked assemblies with that of the DSG-modified monomers in two-dimensional gels suggest that all are composed of only αSyn. Furthermore, the addition of pure monomeric αSyn to cytosols before in vitro cross-linking selectively augmented (i.e. contributed to) the endogenous 80-kDa αSyn species. These data suggest that the mid-Mr species of αSyn we detect in vivo and in vitro represent homo-oligomers rather than monomers bound to one or more distinct heterologous proteins. Indeed, we provide multiple criteria that rule strongly against the αS-60, -80, or -100 species being hetero-oligomers of αSyn monomers bound to a known αSyn-associated protein, to wit: exclusion of candidates as per supplemental Table 1; detection of oligomerization intermediates (dimers, trimers) under certain conditions and occurrence of molecular mass shifts by adding epitope tags to αSyn; co-IP of differentially tagged αSyn molecules in a 60-kDa oligomer; detection of the oligomeric species when αSyn is expressed in bacteria). On the basis of all currently available data, we hypothesize that the ∼60, 80, and 100 species observed in vivo are either composed of increasing numbers of monomers (4/5/6 or 4/6/8), or the αS-80 and 100 species represent conformers of the major 60-kDa cellular form. Parsimony suggests that the latter is likely to be a tetramer when our new data are integrated with the multiple lines of independent evidence (e.g. sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation; scanning transmission electron microscopy analysis; circular dichroism; NMR structure) that αSyn can exist in part as a helically folded tetramer (1, 6–8).

We incorporated several key controls to support the physiological relevance of our cross-linking approach. First, in vivo cross-linking of endogenous αSyn by DSG (and DSS) occurred under the same conditions that allowed the observation of well established endogenous oligomeric proteins such as DJ-1, voltage-dependent ion channel, or Drp-1 in the same cells, whereas monomeric proteins such as Ran or Parkin were only detected at monomeric positions. Second, the αS-60, -80, and -100 species were all reduced quantitatively to monomers when the cleavable cross-linker DSP was applied to intact cells and then cleaved. Third, trapping of these species could not be achieved with certain other cross-linkers, e.g. the short spacer length DFDNB, suggesting that specific atomic spacing is required for successful stabilization of the species and that our observations are not just caused by non-specific cross-linking. Fourth, by using in vivo (intact cell) cross-linking as our standard method, by performing ultracentrifugation at extremely high speeds, by using various different lysis methods, and by demonstrating the absence of the synaptic vesicle protein synaptobrevin-2 in our neuronal cytosols, we could essentially rule out the possibilities that either endogenous membrane vesicles or membrane changes induced by cell lysis were responsible for the αSyn species we observed. Fifth, the pattern of oligomers obtained by non-specifically cross-linking pure, unfolded αSyn monomers in vitro is entirely distinct from the endogenous cellular oligomers we describe. Sixth, cellular co-expression of differentially tagged αSyn molecules and in vivo cross-linking leads to the co-IP of the two different monomers in the tetramers. Seventh, the confirmation of our basic findings by studying β-synuclein or else αSyn lacking an intact NAC domain (Δ71–82) has special interest, as it argues strongly against pathogenic (Parkinson disease-related) aggregation events being responsible for the detection of the mid-Mr αSyn after cross-linking, thus underlining the physiological relevance of our findings.

The central purpose of the current study, as was the case for our earlier report (Bartels et al. (1), was to attempt to detect and characterize the physiological state of endogenous αSyn in cells, especially neurons. Such basic understanding is required to interpret the widely discussed concepts of “misfolding” and “pathological aggregation” of αSyn in human brain diseases. Although three recent papers strongly suggested the existence of oligomeric, folded αSyn in nature (1, 6, 7), the development of a facile and efficient in vivo cross-linking protocol we describe and validate here should now allow many laboratories to readily detect the oligomeric state of both endogenous and overexpressed αSyn in cellular models. We expect the method to be a useful tool for many further studies analyzing the effects of various cell stressors and of Parkinson disease-causing αSyn mutations, allowing dynamic studies of their effects on the native cellular state of αSyn. However, quantitative conclusions about the absolute abundance of the various mid-Mr species versus monomeric αSyn are limited by the efficiency of in vivo cross-linking. The protocol we describe allows the detection of apparent endogenous oligomers and residual free monomers in living cells while largely avoiding αSyn-immunoreactive high Mr smears, which we consider to arise from nonspecific cross-linking occurring only at high DSG concentrations.

Although the current study purposely focused on the development and exploitation of in vivo and in vitro cross-linking methods, the results can and should be interpreted in the context of our prior use of numerous other analytical methods (αSyn purification from cells and concentration in the purified state, sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation, scanning transmission electron microscopy, CD (1)) that collectively support the hypothesis that the principal endogenous form of αSyn in cells is a folded tetramer of ∼58 kDa. This model, which now requires more widespread confirmation, is also consistent with emerging data from other laboratories (6–8, 16).

Very importantly, the striking sensitivity of the major ∼60-kDa putative tetramer to cell lysis provides a strong caveat for the widespread study of cellular αSyn by conventional biochemical methods. This behavior of endogenous αSyn was distinct from that of endogenous DJ-1, voltage-dependent ion channel, GAPDH, DRP-1, and HSP-70, all of which showed their expected oligomeric species in the very same cells regardless of whether cross-linking was done in vivo or in vitro (see Fig. 5A). This unusual lability of cellular αSyn oligomers once cells are broken open is in agreement with an earlier study that detected intracellular αSyn oligomers (size not assessable) by FRET/fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy measurements in intact cells but not by other methods after cell lysis (16). The lack of in vitro stability is unfortunate for the αSyn research community but must be taken into account in designing future studies of this key protein in Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases and other human synucleinopathies. Methods performed in intact cells (including new ways of performing FRET or cross-linking) and careful attention to the assembly state and folding of αSyn after its purification from brain tissue will now be necessary. We speculate that an unknown bioorganic molecule (perhaps a small lipid) normally stabilizes the endogenous tetramer (and perhaps higher oligomers) in intact cells, but this moiety is diluted and lost upon cell lysis except when very high macromolecular conditions are preserved during lysis (see Fig. 5D) or else concentration of the purified cellular protein is undertaken (1). The identification of such a factor(s) represents in our view an important new experimental goal, as the factor could help regulate αSyn assembly and stability in both health and disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Rice and M. Jin for assistance with primary neuronal cultures, V. Sathananthan for helping to optimize the DSG cross-linking protocol, N. Exner and C. Haass for generously providing mAb 15G7, A. Narla for helpful discussions about HEL cells, M. LaVoie and A. Chen for critical reading of the manuscript, G. Tofaris for repetition of key experiments, and members of the Selkoe laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Fidelity Biosciences Research Initiative.

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

- αSyn

- α-synuclein

- βSyn

- β-synuclein

- DIV

- days in vitro

- DSG

- disuccinimidyl glutarate

- DSS

- disuccinimidyl suberate

- DSP

- dithiobis(succinimidyl) propionate

- DFDNB

- 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

- HEL

- human erythroleukemia cell

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- LDS

- lithium dodecyl sulfate

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- pAb

- polyclonal antibody

- M17D

- human neuroblastoma BE(2)-M17 cell

- PI

- protease inhibitors

- TX-100

- Triton X-100

- RT

- room temperature

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- Sbr-2

- synaptobrevin-2

- WB

- Western blot

- NAC

- non-amyloid component.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartels T., Choi J. G., Selkoe D. J. (2011) α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 477, 107–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fauvet B., Mbefo M. K., Fares M. B., Desobry C., Michael S., Ardah M. T., Tsika E., Coune P., Prudent M., Lion N., Eliezer D., Moore D. J., Schneider B., Aebischer P., El-Agnaf O. M., Masliah E., Lashuel H. A. (2012) α-Synuclein in central nervous system and from erythrocytes, mammalian cells, and .Escherichia coli exists predominantly as disordered monomer., J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15345–15364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polymeropoulos M. H., Lavedan C., Leroy E., Ide S. E., Dehejia A., Dutra A., Pike B., Root H., Rubenstein J., Boyer R., Stenroos E. S., Chandrasekharappa S., Athanassiadou A., Papapetropoulos T., Johnson W. G., Lazzarini A. M., Duvoisin R. C., Di Iorio G., Golbe L. I., Nussbaum R. L. (1997) Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science 276, 2045–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spillantini M. G., Schmidt M. L., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q., Jakes R., Goedert M. (1997) α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinreb P. H., Zhen W., Poon A. W., Conway K. A., Lansbury P. T., Jr. (1996) NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry 35, 13709–13715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang W., Perovic I., Chittuluru J., Kaganovich A., Nguyen L. T., Liao J., Auclair J. R., Johnson D., Landeru A., Simorellis A. K., Ju S., Cookson M. R., Asturias F. J., Agar J. N., Webb B. N., Kang C., Ringe D., Petsko G. A., Pochapsky T. C., Hoang Q. Q. (2011) A soluble α-synuclein construct forms a dynamic tetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17797–17802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trexler A. J., Rhoades E. (2012) N-terminal acetylation is critical for forming α-helical oligomer of α-synuclein. Protein Sci. 21, 601–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Westphal C. H., Chandra S. S. (2013) Monomeric synucleins generate membrane curvature. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1829–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kahle P. J., Neumann M., Ozmen L., Muller V., Jacobsen H., Schindzielorz A., Okochi M., Leimer U., van Der Putten H., Probst A., Kremmer E., Kretzschmar H. A., Haass C. (2000) Subcellular localization of wild-type and Parkinson's disease-associated mutant α -synuclein in human and transgenic mouse brain. J. Neurosci. 20, 6365–6373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baulac S., LaVoie M. J., Strahle J., Schlossmacher M. G., Xia W. (2004) Dimerization of Parkinson's disease-causing DJ-1 and formation of high molecular weight complexes in human brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 27, 236–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee B. R., Kamitani T. (2011) Improved immunodetection of endogenous α-synuclein. PLoS One 6, e23939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]