A chemical screen identifies the cytokinin-like phenyl-adenine as a potent shoot inducer that functions through dual actions of cytokinin receptor activation and suppression of cytokinin degradation.

Abstract

In vitro shoot regeneration is implemented in basic plant research and commercial plant production, but for some plant species, it is still difficult to achieve by means of the currently available cytokinins and auxins. To identify novel compounds that promote shoot regeneration, we screened a library of 10,000 small molecules. The bioassay consisted of a two-step regeneration protocol adjusted and optimized for high-throughput manipulations of root explants of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) carrying the shoot regeneration marker LIGHT-DEPENDENT SHORT HYPOCOTYLS4. The screen revealed a single compound, the cytokinin-like phenyl-adenine (Phe-Ade), as a potent inducer of adventitious shoots. Although Phe-Ade triggered diverse cytokinin-dependent phenotypical responses, it did not inhibit shoot growth and was not cytotoxic at high concentrations. Transcript profiling of cytokinin-related genes revealed that Phe-Ade treatment established a typical cytokinin response. Moreover, Phe-Ade activated the cytokinin receptors ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE3 and ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE4 in a bacterial receptor assay, albeit at relatively high concentrations, illustrating that it exerts genuine but weak cytokinin activity. In addition, we demonstrated that Phe-Ade is a strong competitive inhibitor of CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE enzymes, leading to an accumulation of endogenous cytokinins. Collectively, Phe-Ade exhibits a dual mode of action that results in a strong shoot-inducing activity.

The capacity to regenerate shoots, broadly applied for tissue culture purposes or biotechnological breeding methods (Duclercq et al., 2011), is not an uncommon trait of plants; nevertheless, many species remain recalcitrant. Thus, a major challenge for tissue culture practices is the development of efficient protocols in which plant growth regulators (PGRs) are pivotal. Currently, besides natural plant hormones, a whole range of synthetic PGRs is being applied in tissue culture. For example, compared with natural cytokinins, the synthetic cytokinin thidiazuron is more effective as an inducer of shoot formation in some plants (van Staden et al., 2008), and because it can substitute both for cytokinin and auxin, thidiazuron is also widely used for callus induction and somatic embryogenesis (Murthy et al., 1998). In a continuous search for new hormone-like substances to expand the collection of suitable compounds and to increase the efficiency of specific protocols, libraries of structural variants of known PGRs or of structurally unrelated small molecules are being tested (Kumari and van der Hoorn, 2011). Whereas the first approach mainly results in compounds that function in a similar but more efficient way than known PGRs, the latter tactic may potentially yield compounds that exhibit an alternative mode of action. Successful chemical screens, for instance, have led to the identification of growth-promoting auxin analogs (Savaldi-Goldstein et al., 2008), root growth-promoting cytokinin antagonists (Arata et al., 2010), and the non-auxin-like lateral root inducer naxillin (De Rybel et al., 2012).

Although shoot regeneration is a complex developmental process, a lot of insights have been gained from studies on the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Meng et al., 2010). In general, two major phases are distinguished in shoot organogenesis: the acquisition of competence and the commitment to form shoots (Cary et al., 2002). In the two-step shoot regeneration protocol described by Valvekens et al. (1988) for Arabidopsis root explants, these two phases are accomplished through incubation on auxin-rich callus induction medium (CIM) followed by incubation on cytokinin-rich shoot induction medium (SIM). During the CIM treatment, auxin maxima, essential for the acquisition of competence, are established in the pericycle cells (Atta et al., 2009; Pernisová et al., 2009); then, tissues proliferate that resemble premature roots (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). The auxin treatment also leads to a broad transcriptional modulation (Che et al., 2006) including a strong and local up-regulation of the ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE4 (AHK4) cytokinin receptor (Gordon et al., 2009). The subsequent incubation on SIM converts the premature roots into shoots, particularly in those regions where the cytokinin receptor genes are up-regulated (Pernisová et al., 2009). Indeed, in these regions, cytokinin signaling is sufficiently high to activate WUSCHEL and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS expression (Gordon et al., 2009), which are critically important for shoot meristem development (Gallois et al., 2002; Lenhard et al., 2002).

The importance of the cytokinin response and cytokinin-controlled genes in shoot regeneration has also been demonstrated by genetic approaches. For example, the constitutive expression of cytokinin signaling genes, such as CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE INHIBITOR1 (CKI1; Kakimoto, 1996) and ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR2 (ARR2; Hwang and Sheen, 2001), eliminates the requirement for cytokinins in SIM. Interestingly, however, overexpression of ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 (ESR1) and ESR2, which are not directly involved in cytokinin metabolism or signaling, also confers cytokinin-independent shoot formation from Arabidopsis root explants. Still, these lines are not insensitive to cytokinins, since their regeneration efficiency can be increased by cytokinin application (Banno et al., 2001; Ikeda et al., 2006). Whereas for all these transgenics pretreatment with the synthetic auxin 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) remains a prerequisite for shoot formation, overexpression of WOUND-INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION1 abolishes the need both for 2,4-D in CIM and cytokinins in SIM. Analysis of the regeneration process in these plants revealed that the meristems originated from another cell type than in wild-type plants, implying that there is a second regeneration pathway (Iwase et al., 2011) and opening perspectives to identify alternative regeneration protocols.

Because shoot regeneration can be achieved by cytokinin application to the cultivation medium but also using transgenics approaches, we reasoned that it would be conceivable to obtain shoot formation with cytokinin-like compounds or downstream effectors different from cytokinins. Therefore, we set out to search for novel shoot-inducing compounds by combining a chemical screen with the regeneration procedure described for Arabidopsis by Valvekens et al. (1988). First, we optimized the protocol to allow high-throughput screening of a chemical library. Of all compounds tested, only one, phenyl-adenine (Phe-Ade), stimulated shoot formation. To assess the specificity of this compound, we scored its activity in typical cytokinin-related processes. Then, to unravel the mode of action of Phe-Ade, we profiled the expression of cytokinin-related marker genes in response to Phe-Ade, analyzed its effect on the regeneration of Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants, assessed its perception by the cytokinin receptors, and tested its interaction with different CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE (CKX) enzymes. Based on our results, we conclude that Phe-Ade is a weak cytokinin that strongly inhibits endogenous cytokinin degradation.

RESULTS

A Chemical Screen Reveals Phe-Ade as a Potent Shoot-Inducing Molecule

To identify novel compounds that promote shoot regeneration, we first optimized the regeneration protocol of Valvekens et al. (1988) allowing high-throughput manipulations (Supplemental Procedure S1; Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S1). In short, 7-mm root explants with a root apical meristem were incubated on CIM containing 2,4-D and kinetin for 4 d in petri dishes. Then, the explants were transferred to 96-well plates, two per well, containing solid SIM without 3-indoleacetic acid (IAA) and with either 10 µm 2-isopentenyladenine (2-iP) or 10 µm of the individual compounds of a diversity-oriented library of 10,000 small molecules (molecular weight less than 500 g mol−1). To facilitate the observation of shoot primordia, we used the accession C24 GAL4-GFP enhancer trap line M0167 (Haseloff, 1999). This line visualizes the expression of the shoot marker LIGHT-DEPENDENT SHORT HYPOCOTYLS4 (LSH4; Cary et al., 2002). LSH4 expression was scored after 12 d on SIM and shoot formation 7 d later.

Of all compounds tested, only one, Phe-Ade (N-phenyl-9H-purin-6-amine) induced LSH4 expression and shoot formation (Fig. 1). None of the other compounds activated LSH4 expression or induced shoot primordia or shoots. To evaluate the shoot-inducing capacity of Phe-Ade, we tested different concentrations within the activity range of 2-iP in the 96-well format. Because Arabidopsis accession C24 is highly regenerative (Supplemental Fig. S1E), counting the number of shoots formed per explant in the 96-well plate format was difficult. Therefore, the projected area encompassed by the emerging shoots was adopted as a quantitative measure. As shown in Figure 2A, at the lower concentrations, Phe-Ade was a better inducer of shoot formation than 2-iP, and at the highest concentration tested, it performed equally well.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and activity of Phe-Ade. A, Chemical structure. B, LSH4 expression after 12 d (top panel) and shoot induction after 19 d (bottom panel) of SIM incubation containing 10 µm Phe-Ade. Bars = 1 mm.

Figure 2.

Phe-Ade is an efficient inducer of shoot formation on C24 and Col-0 root explants. A, Regeneration of C24 root explants after 15 d on SIM with Phe-Ade or 2-iP using shoot area as a quantitative measure (see “Materials and Methods”). B, Regeneration rate of Col-0 root explants expressed as a percentage of responsiveness (i.e. the average number of root explants forming at least one shoot). Responsive explants were counted 14 d after transfer to SIM. Data represent averages of three biological repeats each with 19 root explants. Different letters indicate statistical differences evaluated with Duncan’s multiple range test in conjunction with ANOVA. Error bars represent se.

To further assess the potential of Phe-Ade as a shoot inducer, its effect on shoot regeneration on roots of accession Columbia (Col-0), which has been reported to have a lower shoot regeneration capacity (Siemens et al., 1993; Cary et al., 2002), was tested in petri dishes. The regeneration rate was quantified by counting the number of responsive explants (i.e. explants that produced one or more shoots) on different concentrations of Phe-Ade and 2-iP. As shown in Figure 2B, the effect of both compounds was optimal at a concentration of 10 µm, confirming the results obtained with the 96-well plates for accession C24 (Fig. 2A). Moreover, Phe-Ade had a stronger shoot-inducing effect than 2-iP for the tested concentration range, and the difference in the regeneration rate under optimal, suboptimal, or supraoptimal Phe-Ade concentrations was only moderate (Fig. 2B), indicating that Phe-Ade is effective at a much broader concentration range than 2-iP. When the concentration of Phe-Ade was lowered to 0.1 µm or increased to 500 µm, induction of shoots no longer occurred (data not shown).

Phe-Ade Provokes Cytokinin-Like Biological Responses

To assess whether Phe-Ade affected other biological processes besides shoot regeneration, its activity in different cytokinin-mediated processes was evaluated. Col-0 seeds were germinated on medium containing 10 µm Phe-Ade, 10 µm 2-iP, or 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a control, and the development of the plants was followed over time. At the earlier time points, compared with the control, the plants grown on 2-iP and Phe-Ade exhibited a stunted appearance, anthocyanin formation, and serrated leaf margins (Fig. 3A), which are all cytokinin responses in Arabidopsis (Depuydt et al., 2008). Interestingly, after 3 weeks, 2-iP-treated plants showed in general a strongly reduced shoot size compared with the controls, but this negative effect was not observed for Phe-Ade treatment (Fig. 3B). Another developmental aspect of cytokinin treatment is the inhibition of root elongation (Auer, 1996), and both 2-iP and Phe-Ade treatment provoked this response (Fig. 3A). When the extent of the root growth inhibition was quantified for seedlings grown on different concentrations of Phe-Ade or 2-iP, it was clear that after 6 d, Phe-Ade showed a stronger root growth inhibition than 2-iP for all concentrations tested (Fig. 3C). Moreover, evaluation of the plants after 21 d of growth on 10 µm of the PGRs showed that Phe-Ade, in contrast to its effect on shoot growth, clearly inhibited root elongation stronger than 2-iP (Fig. 3D): the root length after Phe-Ade or 2-iP treatment was 12% or 19% of the DMSO control, respectively. Finally, the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) callus growth bioassay was reassessed with different concentrations of 2-iP and Phe-Ade. Phe-Ade only moderately induced callus in this assay, confirming the data by Zatloukal et al. (2008). Interestingly, however, at 100 µm, when commonly used cytokinins were toxic and caused cell death (Zatloukal et al., 2008; Pertry et al., 2009), Phe-Ade stimulated the division of the tobacco callus cells (Fig. 3E). Altogether, these results illustrate that Phe-Ade, in contrast to previous reports, has a cytokinin activity that is comparable to that of 2-iP. Importantly, when compared with 2-iP, negative effects such as the inhibition of shoot growth and the induction of cell death at higher concentrations are not observed upon Phe-Ade treatment.

Figure 3.

Phe-Ade exhibits several cytokinin-like activities. A, Phenotype of Col-0 plants grown for 1, 2, or 3 weeks in the presence or absence of 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP. Notice the stunted growth, anthocyanin accumulation, serrated leaf margins, and inhibited root growth. Bars = 1 mm. B, Overview of plants grown for 3 weeks in the presence or absence of 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP. In general, shoot growth was only inhibited by 2-iP. Bars = 10 mm. C, Root elongation inhibition assay on Col-0 seedlings grown for 6 d on different concentrations of 2-iP or Phe-Ade. Error bars represent se (n ≥ 20). D, Root growth over a period of 20 d on 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP. Error bars represent se (n ≥ 20). E, Tobacco callus assay. Phe-Ade is not cytotoxic at high concentrations, in contrast to 2-iP. Error bars indicate se (n = 6).

Transcript Profiling Suggests That Phe-Ade Triggers a Cytokinin-Like Gene Regulation

To gain insight into the mode of action of Phe-Ade, its effect on the expression of cytokinin-related genes was examined in roots and leaves (Supplemental Table S2). To this end, 14-d-old Arabidopsis Col-0 plants were incubated in liquid medium containing 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP for 15, 30, and 60 min and 1, 3, and 7 d. Incubation in hormone-free medium served as a negative control. Generally, in shoot tissues, the expression profiles obtained upon Phe-Ade treatment were comparable to those on 2-iP (Fig. 4). The primary cytokinin response genes, the type A ARRs ARR5, ARR15, and ARR16, showed a typical transient change in expression, with a very fast and strong up-regulation after 15 min of PGR treatment and the subsequent gradual dampening of induction due to feedback mechanisms (Fig. 4). The transcript levels of the B-type ARRs ARR2, ARR10, and ARR14, coding for transcription factors that induce cytokinin response genes, were not altered by Phe-Ade or 2-iP (data not shown). The cytokinin biosynthesis genes ISOPENTENYLTRANSFERASE3 (IPT3) and IPT7 were down-regulated after longer periods of Phe-Ade and 2-iP treatment, pointing to the establishment of cytokinin homeostasis mechanisms (Fig. 4). The expression of other IPTs, IPT1, IPT2, and IPT8, as well as the cytokinin-activating genes LONELY GUY6 (LOG6) and LOG8, and the cytochrome P450 gene CYP735A2, implicated in the biosynthesis of trans-zeatin (tZ), was not altered by either PGR (data not shown). The very fast up-regulation by Phe-Ade and 2-iP of the CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE (CKX) genes CKX3, CKX4, and CKX5, mediating the irreversible degradation of cytokinins, further supports the activation of homeostatic mechanisms (Fig. 4). CKX2 and CKX6 expression was only activated after longer incubation periods with both PGRs, but CKX2 up-regulation by Phe-Ade was strongly delayed compared with that by 2-iP (Fig. 4). The transcript levels of CKX1 and CKX7 were not altered by either compound (data not shown). Cytokinin homeostasis is further established through irreversible conjugation into inactive N-glucosides by UDP-GLUCOSYL TRANSFERASEs (UGTs; Wang et al., 2011). Expression of UGT76C2 (Fig. 4), but not of UGT76C1 (data not shown), was up-regulated in response to Phe-Ade and 2-iP treatment, although the induction by Phe-Ade was slightly delayed. The expression of the O-glucosyltransferases UGT73C5 and UGT85A1 (Fig. 4), but not of UGT73C1 (data not shown), putatively mediating the reversible conjugation of cytokinins (Hou et al., 2004), was induced after longer incubation times with both PGRs. Finally, neither Phe-Ade nor 2-iP treatment affected the expression of the cytokinin receptor genes AHK2, AHK3, and AHK4 (data not shown). Similar expression trends were observed in the root tissues for all tested genes (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Transcript profiling of cytokinin-related genes in Col-0 shoot tissues at different time points of 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP treatment. Different letters indicate statistical differences between the samples evaluated with the Tukey’s range test in conjunction with ANOVA. Asterisks indicate statistical differences from the hormone-free control, evaluated with a two-tailed Student’s t test and adjusted with the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate method. Error bars represent se (n = 4).

Taken together, the expression profiles obtained upon Phe-Ade treatment imply a typical cytokinin-mediated gene regulation and an activation of cytokinin homeostasis mechanisms. The lack of significant differences in the kinetics and in the amplitude of the expression profiles upon Phe-Ade and 2-iP treatment shows that Phe-Ade establishes a cytokinin-like gene regulation.

Importance of Cytokinin Receptors in the Phe-Ade-Induced Responses

The fast induction of expression of the A-type ARRs (Fig. 4) suggests that Phe-Ade acts as a cytokinin. Further evidence for the activation of ARR5 expression by Phe-Ade was obtained by histochemical staining of 14-d-old Col-0 plants harboring an ARR5:GUS reporter fusion treated for 5 d with 10 µm Phe-Ade or 10 µm 2-iP on solid medium. As shown in Figure 5A, both compounds induced ARR5 expression to the same extent and in the same tissues (especially the shoot apical meristem and the roots). Next, to assess whether a specific cytokinin receptor was implicated in the ARR5 induction, similar analyses were done using the double cytokinin receptor mutants ahk2 ahk3, ahk2 ahk4, and ahk3 ahk4. As observed by Pertry et al. (2010), the basal ARR5 expression level in these receptor mutants was elevated compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 5A). Both Phe-Ade and 2-iP induced ARR5 expression in these mutants to the same extent with a similar tissue specificity. Compared with treated Col-0 plants, the expression level was much higher in ahk2 ahk4 and ahk3 ahk4 mutants and occurred throughout the plant, while in ahk2 ahk3 mutants, it occurred especially in the root (Fig. 5A). These results imply that the Phe-Ade-mediated cytokinin response is not dependent on a specific cytokinin receptor, although their individual contributions to ARR5 induction are not the same. Similar conclusions could be drawn when the effect of Phe-Ade and 2-iP on the development of the ahk double mutants was evaluated. Compared with the wild-type controls, the DMSO-treated cytokinin receptor mutants had longer roots and smaller rosette leaves (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S2), which is in agreement with previous reports (Nishimura et al., 2004). Phe-Ade and 2-iP treatment of, in particular, ahk3 ahk4 but also of ahk2 ahk4 plants had only moderate effects on the rosette size, the root growth, the bleaching of the shoots, the anthocyanin production, and the serrations of the leaf margins (Supplemental Fig. S2). In contrast, treatment of the ahk2 ahk3 mutant with both PGRs did cause considerable effects on plant development (Supplemental Fig. S2), which were comparable to those described for the wild-type plants (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). After 1 week, anthocyanin accumulation and a strongly reduced root elongation were observed. After 2 and 3 weeks, 2-iP showed a strong inhibition of rosette growth, while the rosettes of plants treated with Phe-Ade were comparable in size to the DMSO controls; leaf margins were serrated with both compounds. Thus, whereas AHK2 and AHK3 have minor contributions, a functional AHK4 receptor seems essential and sufficient for the evaluated cytokinin-like responses triggered by both Phe-Ade and 2-iP.

Figure 5.

Interaction between Phe-Ade and the cytokinin receptors. A, ARR5:GUS expression in 14-d-old plants of Col-0 and the cytokinin receptor double mutants ahk2 ahk3, ahk2 ahk4, and ahk3 ahk4 treated for 5 d with 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP. B, Root elongation inhibition assay on Col-0 and on double ahk mutant seedlings grown for 7 d on 10 µm 2-iP or Phe-Ade. Error bars represent se (n ≥ 10). C, In silico binding of Phe-Ade in the active site of AHK4. D, Effect of Phe-Ade, adenine (Ade), and tZ on the specific binding of 2 nm [3H]tZ in a live-cell hormone-binding assay employing E. coli cells expressing AHK4. NS, Nonspecific binding in the presence of a 5,000-fold excess of unlabeled tZ. Error bars indicate se (n = 3). E, Activation of the cytokinin receptors AHK3 and AHK4 by Phe-Ade and tZ in the E. coli receptor assay. Error bars indicate se (n = 3). F, Regeneration rate of root explants of Col-0 and the double ahk mutants on 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP. Error bars indicate se. The data are averages of three biological repeats with 10 explants each. WT, Wild type.

With the availability of the crystal structure of AHK4 (Hothorn et al., 2011; Protein Data Bank identifier 3t4q), we assessed AHK4 Phe-Ade binding in silico using AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010). Although Phe-Ade docked into AHK4, in contrast to tZ, it lacked the interaction of the polar hydroxyl group (Fig. 5C); therefore, only a weak interaction of −5.6 kcal mol−1 was predicted. This prediction was confirmed with a “live-cell hormone-binding assay” using AHK4-expressing Escherichia coli cells (Romanov et al., 2005). In this assay, the potential of different concentrations of Phe-Ade to compete with radiolabeled tZ for AHK4 binding was evaluated; adenine was used as a negative control. As shown in Figure 5D, Phe-Ade reduced the binding of labeled tZ, but only at relatively high concentrations.

The subsequent activation of the cytokinin receptors was demonstrated using AHK3- and AHK4-expressing E. coli cells carrying a cytokinin-activated reporter gene, cps::lacZ (Suzuki et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001; Spíchal et al., 2004). Although Phe-Ade activated both receptors (Fig. 5E), the required concentration was 1,000-fold higher than for tZ, which is in agreement with the results of the competition assay.

Finally, the importance of the cytokinin receptors in the shoot-inducing activity of Phe-Ade was tested by quantifying the shoot regeneration rate of root explants from the double cytokinin receptor mutants on Phe-Ade and 2-iP. For both compounds, no regeneration occurred for ahk2 ahk4 and ahk3 ahk4 (Fig. 5F), suggesting that AHK4 is essential for this developmental process. Indeed, treatment of root explants of the ahk2 ahk3 mutant, in which the AHK4 receptor is functional, with Phe-Ade and 2-iP resulted in the formation of a comparable number of shoots. However, the regeneration rate of this mutant was up to 8-fold lower compared with that of Col-0 explants (Fig. 5F), implying that although AHK4 is essential it is not sufficient for a wild-type regeneration level. Hence, shoot regeneration by both Phe-Ade and 2-iP depends on cytokinin perception through all three AHKs.

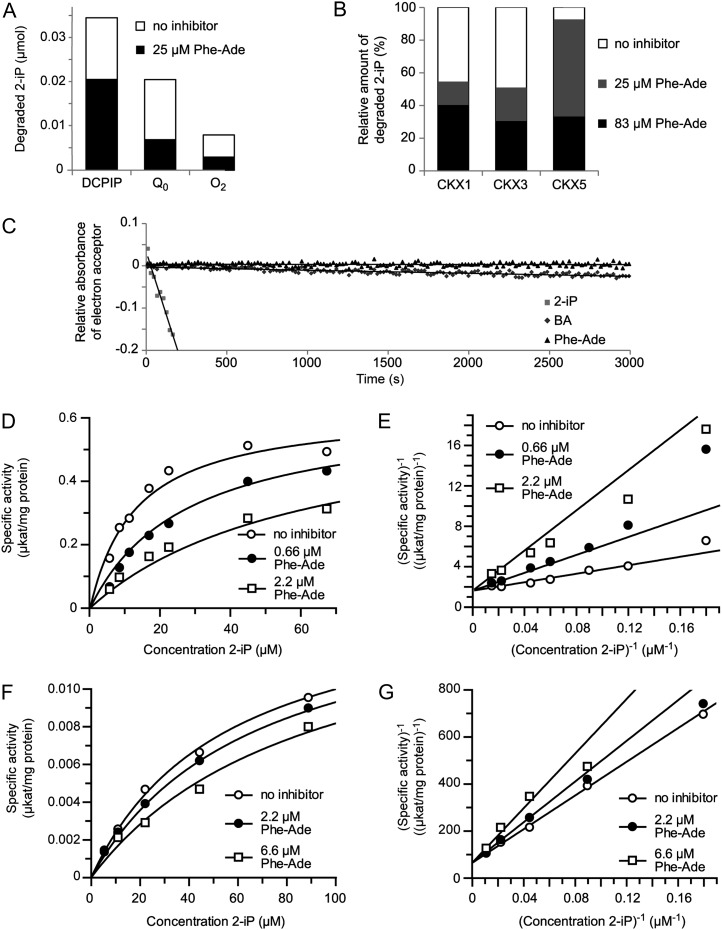

Phe-Ade Is a Competitive Inhibitor of CKX Enzymes

Although Phe-Ade is only a weak activator of the cytokinin receptors, its activity in the shoot regeneration assay nevertheless is strong. Moreover, the induced expression of the cytokinin metabolism genes CKX2 and UGT76C2 in response to Phe-Ade is delayed when compared with 2-iP (Fig. 4). Overall, these observations suggested that, besides its direct but weak cytokinin activity, another indirect mode of action could be at the basis of the biological activity of Phe-Ade. Based on the transcript profiling results (Fig. 4), a differential regulation of the most important cytokinin metabolism genes was ruled out as a potential mechanism. So we hypothesized that Phe-Ade would affect cytokinin degradation; therefore, the ability of Phe-Ade to inhibit the activity of CKX enzymes was tested. Using the method of Libreros-Minotta and Tipton (1995), the degradation of 2-iP by recombinant CKX2 in the absence or presence of Phe-Ade was measured. As observed previously (Galuszka et al., 2007), CKX2 exhibited oxidase activity, but it was much more active as a dehydrogenase (Fig. 6A). More importantly, however, both in the dehydrogenase mode (with the synthetic electron acceptors 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol [DCPIP] and 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone [Q0]) and the oxidase mode (with oxygen as electron acceptor), Phe-Ade inhibited the degradation of 2-iP (Fig. 6A). To determine whether the reduced degradation of 2-iP resulted from a competitive degradation of Phe-Ade as an alternative substrate for CKX2, we omitted 2-iP from the reaction mixture and monitored the consumption of the electron acceptor DCPIP in the presence of only Phe-Ade. Benzyladenine (BA), which is reported to be a very weak substrate for CKX enzymes (Frébortová et al., 2007), was used as a control. As shown in Figure 6C, BA was degraded by CKX2 very slowly, whereas Phe-Ade was not.

Figure 6.

Phe-Ade is an inhibitor of CKX activity. A, CKX2-inhibiting activity of Phe-Ade in dehydrogenase (DCPIP and Q0) and oxidase (O2) mode. The degradation of 2-iP (83 µm) was determined by measuring the absorbance of the Schiff base at 352 nm (see “Materials and Methods”). B, Phe-Ade is an inhibitor of CKX1, CKX3, and CKX5. 2-iP (60 µm) degradation was determined by subtracting the concentration after 45 min from the concentration before the reaction and is expressed relative to the amount of degraded 2-iP in the absence of inhibitor. C, CKX2 degradation of 2-iP, BA, and Phe-Ade (166 µm). 2-iP and BA are, respectively, a strong and a weak substrate, while Phe-Ade is not a substrate of CKX2. Degradation was determined as bleaching of the absorbance of the electron acceptor DCPIP at 600 nm and is expressed relative to the same reaction without substrate. D to G, Raw data (D and F) and Lineweaver-Burk plots (E and G) of CKX2 (D and E) and CKX7 (F and G) activity in the absence or presence of Phe-Ade. Degradation rates were determined by continuously measuring the bleaching of DCPIP for different concentrations of 2-iP and Phe-Ade. Each combination was repeated at least three times.

To determine the specificity of CKX inhibition by Phe-Ade, CKX1-, CKX3-, CKX5-, and CKX7-mediated 2-iP degradation was tested using different methods. For the first three enzymes, the concentration of 2-iP was measured by ultra-performance liquid chromatography in the presence or absence of Phe-Ade, which showed that Phe-Ade inhibited the activity of each of these CKXs (Fig. 6B). For CKX7, and also for CKX2, a continuous assay was done where the reduction of DCPIP with different concentrations of 2-iP as a substrate and Phe-Ade as the inhibitor was measured, allowing the calculation of the apparent Km (Frébort et al., 2002) and the enzyme-inhibitor dissociation constant (Ki). Phe-Ade proved to have significantly lower Ki values compared with the apparent Km for 2-iP with both enzymes (Table I; Fig. 6, D–G), demonstrating its capacity as a very potent CKX inhibitor. The Lineweaver-Burk double-reciprocal plots (Fig. 6, E and G) clearly established the competitive manner of inhibition.

Table I. Kinetic parameters calculated from Figure 6, D to G.

| Parameter | CKX2 | CKX7 |

|---|---|---|

| Vmax (µkat mg−1 protein) | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.016 ± 0.001 |

| Km (µm) | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 55.5 ± 5.6 |

| Ki (µm) | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 10.7 ± 1.6 |

Phe-Ade Treatment Increases the Endogenous Cytokinin Content of Arabidopsis Plants

To validate the importance of Phe-Ade as a CKX inhibitor in planta, endogenous cytokinin levels were determined after 1 or 3 d of Phe-Ade or 2-iP treatment of 14-d-old Arabidopsis plants. One day after 2-iP treatment, the levels of cytokinin bases, ribosides, and ribotides were extremely elevated, especially for 2-iP and to a lesser extent for tZ metabolites (Table II). Already at this time point, homeostasis mechanisms were activated, because a strong accumulation of N- and O-glucosides was detected (Table II). After 3 d of incubation with 2-iP, the cytokinin glucoside levels further increased, while the free bases were reduced by half (Table II).

Table II. Endogenous cytokinin content of 14-d-old Arabidopsis plants after 1 or 3 d of treatment with 10 µm 2-iP or Phe-Ade.

Data shown are in pmol g−1 fresh weight ± sd (n = 3). cis-Zeatin-O-glucoside (cZOG) was below the detection limit. cZ, cis-Zeatin; iPR, 2-isopentenyladenosine; tZR, trans-zeatin riboside; cZR; cis-zeatin riboside; iPRMP, 2-isopentenyladenosine-5′-monophosphate; tZRMP, trans-zeatin riboside-5′-monophosphate; cZRMP, cis-zeatin riboside-5′-monophosphate; iP9G, 2-isopentenyladenine-9-glucoside; tZ9G, trans-zeatin-9-glucoside; cZ9G, cis-zeatin-9-glucoside; tZOG, trans-zeatin-O-glucoside; tZROG, trans-zeatin riboside-O-glucoside; cZROG, cis-zeatin riboside-O-glucoside.

| Cytokinin Type |

2-iP |

Phe-Ade |

DMSO |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 d | 3 d | 1 d | 3 d | 1 d | 3 d | |

| 2-iP | 5,843.5 ± 1,666.4 | 2,553.2 ± 733.5 | 9.0 ± 0.9 | 63.1 ± 5.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| tZ | 228.7 ± 9.9 | 185.3 ± 10.3 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

| cZ | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| iPR | 768.5 ± 14.6 | 851.5 ± 34.3 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| tZR | 70.7 ± 3.4 | 110 ± 4.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| cZR | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 27.1 ± 1.2 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| iPRMP | 48,320.2 ± 7,023.5 | 62,529.8 ± 11,476.8 | 33.7 ± 0.3 | 957.2 ± 369.2 | 26.9 ± 1.0 | 108.4 ± 36.1 |

| tZRMP | 2,638.1 ± 240.5 | 9,800.3 ± 3,132.7 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 22.8 ± 4.7 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | 17.5 ± 1.9 |

| cZRMP | 216.8 ± 36.4 | 1,386.2 ± 496.3 | 9.4 ± 1.8 | 43.2 ± 20.7 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 13.3 ± 2.7 |

| iP9G | 3,033.0 ± 245.0 | 3,660.1 ± 292.6 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 76.4 ± 7.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| tZ9G | 93.8 ± 5.5 | 264.3 ± 13.6 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.1 |

| cZ9G | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 46.5 ± 4.3 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| tZOG | 59.7 ± 3.5 | 165.4 ± 51.9 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| tZROG | 121.2 ± 22.6 | 243.2 ± 8.4 | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.0 |

| cZROG | 16.6 ± 1.9 | 32.9 ± 4.4 | 1 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

Importantly, the endogenous cytokinin profile obtained upon Phe-Ade treatment differed from that of 2-iP-treated and control plants (Table II), suggesting that Phe-Ade has a different mode of action than 2-iP and implying that it affects cytokinin homeostasis. One day after Phe-Ade incubation, a modest increase in 2-iP levels was measured. Later, after 3 d of incubation, a steady accumulation of the 2-iP base, riboside, and ribotide was detected, confirming that the CKX enzymes were not functioning optimally. The concentration of 2-isopentenyladenine-9-glucoside increased as well, indicating that some level of inactivating glucosylation occurred. The effect of Phe-Ade on the zeatin metabolites remained very low, even after 3 d (Table II). Altogether, these results support an indirect mode of action of Phe-Ade, leading to a distinct increase in endogenous cytokinin levels.

DISCUSSION

Screening of a diversity-oriented chemical library of small molecules as substitutes for cytokinins in SIM in the two-step regeneration protocol starting from Arabidopsis root explants (Valvekens et al., 1988) yielded only Phe-Ade as a shoot-inducing compound, implying that the cytokinin-mediated step in shoot regeneration is difficult to bypass through exogenous chemicals. Phe-Ade had been described as a cytokinin before (Miller, 1961), but compared with other cytokinins it was classified as significantly less active in several typical cytokinin bioassays, such as tobacco callus growth, anthocyanin production in Amaranthus spp. seedlings, and chlorophyll retention of detached wheat (Triticum aestivum) leaves (Hahn and Bopp, 1968; Zatloukal et al., 2008). Consequently, it has only rarely been used as a PGR. Why then does Phe-Ade have such a strong activity as a shoot inducer in the regeneration protocol?

In planta, the effect on shoot and root development, the activation of ARR5 expression, and the fast and strong differential regulation of a set of cytokinin-related marker genes were comparable for Phe-Ade and 2-iP treatment. These results implied that Phe-Ade functioned as a cytokinin. Indeed, as predicted by in silico docking tests, Phe-Ade could bind to the cytokinin receptor AHK4 (and AHK3) in in vitro assays and triggered downstream signaling, albeit only at relatively high concentrations. This moderate activation of the receptors seemed to be in contrast with the strong shoot regeneration activity of Phe-Ade. Nonetheless, AHK4 was essential for Phe-Ade- and 2-iP-mediated regeneration, as reported for tZ-induced shoot formation (Nishimura et al., 2004), but the functionality of all three cytokinin receptors appeared to be imperative for shoot induction. Importantly, several observations suggested that Phe-Ade might have an additional and indirect mode of action. Shoot growth inhibition typically associated with high cytokinin levels was not observed upon Phe-Ade treatment, and at high concentrations, Phe-Ade did not induce cell death in a tobacco callus bioassay. Moreover, the activation of several cytokinin metabolism genes by Phe-Ade was delayed compared with 2-iP treatment.

Since Phe-Ade could possibly target cytokinin homeostasis, cytokinin degradation by different CKX enzymes in the presence or absence of Phe-Ade was assessed using several experimental approaches. The in vitro data clearly demonstrated that Phe-Ade was a strong and competitive inhibitor of these enzymes. Actually, Phe-Ade had been used as a scaffold structure for the generation of a group of analogs that exhibit CKX-inhibiting activity (Zatloukal et al., 2008), supporting our results. Profiling endogenous cytokinin levels validated the relevance of the inhibition of the CKX enzymes in plants upon Phe-Ade treatment. Thus, the activation of the AHKs and the downstream cytokinin signaling during Phe-Ade treatment are caused both by Phe-Ade itself and by the accumulating endogenous cytokinins.

This specific dual mode of action of Phe-Ade has several implications in planta that might explain the strong activity in the shoot regeneration process. (1) 2-iP treatment resulted in a very fast and extremely high accumulation of the cytokinin content in plant tissues, which is likely cytotoxic and causes stress and reduced responsiveness. Although Phe-Ade treatment triggered an increase in the endogenous cytokinin levels as well, the accumulation resulting from CKX inhibition occurred gradually and was much less pronounced, likely preventing cytotoxic and deleterious effects, allowing a continuous developmental response. (2) Since Phe-Ade is a competitive inhibitor of the CKX enzymes, its effect on homeostasis in tissues with increased cytokinin levels is assumed to be less pronounced. Thus, at a certain moment during the incubation on SIM, the level of endogenous cytokinin, accumulating as a result of Phe-Ade action, will become high enough to compete for CKX binding, resulting in a dampening of the Phe-Ade-mediated CKX inhibition. Consequently, the levels of endogenous cytokinins will reach a new homeostatic equilibrium that might favor shoot regeneration. (3) Phe-Ade is a very potent inhibitor of CKX, as suggested by the low Ki values. Hence, relatively low concentrations of Phe-Ade will still cause inhibition of CKX activity, explaining the high regeneration rate under these conditions. (4) Phe-Ade is not degraded by CKXs, and in the root growth inhibition assay it had a stronger effect than 2-iP after prolonged incubation. Because shoot regeneration takes from 11 up to 18 d, these characteristics of Phe-Ade would be beneficial in the regeneration protocol. (5) Since the inhibition of cytokinin degradation affects homeostasis, cytokinin levels will be especially modified by Phe-Ade in those cells or tissues where the CKX enzymes are most active or abundant. Interestingly, CKX1, CKX5, and CKX6 are expressed in the precursors of lateral root primordia and in the root primordia themselves (Werner et al., 2003). As the first step in the regeneration process involves the formation of lateral root-like primordia (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010), it is conceivable that in these tissues, Phe-Ade will affect CKX activity. This would result in a local increase in endogenous cytokinin levels, which is essential to convert the root-like tissue into shoot primordia (Pernisová et al., 2009). Such a localized modification of cytokinin homeostasis could explain why Phe-Ade is a strong shoot inducer but does not perform well in other cytokinin bioassays. Based on several aspects of the shoot biology, we can speculate that Phe-Ade might be efficient for shoot multiplication as well. Indeed, multiple axillary meristems are induced by increased cytokinin levels in the shoot (Kurakawa et al., 2007), local hormone levels are important for the activity of shoot meristems (Kurakawa et al., 2007; Zhao, 2008), and, importantly, CKX2, a target of Phe-Ade, is highly expressed in the shoot (Werner et al., 2003).

In conclusion, Phe-Ade appears to exhibit cytokinin-like activities in a very broad concentration range. It targets the cytokinin receptors and inhibits the activity of CKX enzymes, resulting in an accumulation of endogenous cytokinin levels and an enhanced cytokinin signaling without provoking negative side effects such as cytotoxicity and inhibited shoot growth. Moreover, Phe-Ade only moderately induces callus growth, an aspect that is highly desirable in tissue culture. Thus, its dual mode of action confers attractive properties to Phe-Ade, different from the commonly used cytokinins, which makes Phe-Ade a promising compound to explore in tissue culture practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) marker lines M0223 and M0167 (C24 background) and accessions Col-0 and C24 were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre. The ahk2 ahk3, ahk2 ahk4, and ahk3 ahk4 double mutants (Col-0 background) harboring the ARR5:GUS reporter fusion (D’Agostino et al., 2000) were described previously (Spíchal et al., 2009). Seeds were sterilized by fumigation for 4 h in a desiccator jar with chlorine gas generated by adding 5 mL of concentrated HCl to 100 mL of 5% (v/v) NaOCl. Sterilized seeds were sown on square petri dishes with basal medium [BM; Gamborg’s B5 salts, 0.05% (w/v) 2-(4-morpholino)ethane sulfonic acid (pH 5.8), 2% (w/v) Glc, and 0.7% (w/v) agar]. After a cold treatment at 4°C for 3 d, the plates were placed vertically in a growth chamber at 22°C under a 16-h/8-h light/dark photoperiod (45 µmol m−2 s−1 light irradiance from cool-white fluorescent tungsten tubes).

Optimization of the Shoot Regeneration Assay

To use shoot regeneration as a bioassay in a chemical screen, the protocol of Valvekens et al. (1988) had to be adjusted to allow high-throughput manipulations. A detailed description of the different aspects of the optimization procedure is given in Supplemental Procedure S1. We compared liquid versus solid SIM, explants with or without the root apical meristem, SIM with or without IAA and with different concentrations of 2-iP, and single or multiple explants per well (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S1).

The final protocol was as follows: 7-mm primary root segments containing the root apical meristem were harvested from 7-d-old seedlings grown on BM medium and placed on CIM (BM supplemented with 2.2 µm 2,4-D and 0.2 µm kinetin) for 4 d. Explants were then used for the chemical screen or transferred to SIM (BM supplemented with 10 µm 2-iP or Phe-Ade; no IAA). Hormones were dissolved in DMSO and supplied to the medium after autoclaving. The success rate of shoot formation is expressed as the regeneration rate (number of explants producing at least one shoot).

Chemical Screen

To visualize primordia prior to shoot formation, the chemical screen was executed with root explants of the GAL4-GFP enhancer trap line M0167 in the C24 background using the optimized 96-well protocol. A subset of 10,000 small molecules of the CNS-set (ChemBridge) was provided on 96-well plates by the VIB Compound Screening Facility of Ghent University (Belgium). Compounds were dissolved in DMSO, and after the addition of BM (cooled to 65°C) to a final volume of 200 µL, a compound concentration of 10 µm per well was obtained; the final DMSO concentration was 1%. On each 96-well plate, eight positive controls with 10 µm 2-iP and eight hormone-free negative controls with only 1% DMSO were included. Root explants were pretreated on CIM as described above, and then, two explants were placed into each well. Root explants were evaluated for LSH4 expression after 12 d of SIM incubation as described below. Shoot formation was scored after 19 d.

Microscopy

Explants were imaged directly on the medium using a Leica MZ FLIII stereomicroscope. For fluorescence imaging, a 425- to 460-nm excitation filter was used together with a 470-nm dichromatic beam splitter and a GG475 barrier filter. Images were captured using ProgRess CapturePro 2.8.

Shoot Area Measurement

After 15 d on SIM, the projected area of shoots formed from root explants of accession C24 in individual wells of 96-well plates was quantified based on images analyzed with the Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software. The spatial scale was calibrated using the 7.3-mm diameter of a well as reference. The area was selected by defining an “area of interest” that encompassed the green color range of the shoots. First, for six out of 48 wells per treatment, it was manually confirmed that the software was imaging only the shoots, and if not, the color range was adjusted. The projected area of the shoot was automatically calculated for each well. Afterward, the accurate selection of shoots was manually confirmed for each well.

Cytokinin Bioassays

The cytokinin-mediated inhibition of Arabidopsis root growth was assayed as described previously (Auer, 1996). Col-0 plants were germinated and grown in vertically placed petri dishes under the conditions given above on BM supplemented with 2-iP or Phe-Ade in concentrations ranging from 0.08 to 10 µm. The root length of at least 20 seedlings per treatment was measured after 6 or 7, 14, and 21 d.

To assess the effect of these compounds on general plant development, Col-0 plants were germinated and grown on BM with 10 µm 2-iP or Phe-Ade. Anthocyanin production, leaf shape, and general plant stature were evaluated after 1, 2, and 3 weeks.

For the visualization of ARR5 expression, Col-0 plants or the double cytokinin receptor mutants carrying an ARR5:GUS fusion were grown under the same conditions described above, and histochemical GUS stainings were done after 5 d. Therefore, plant material was submerged in 90% (v/v) acetone at 4°C for 30 min, rinsed in 100 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), and transferred to a GUS staining solution (1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide, 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100, and 100 mm Na2HPO4 [pH 7.0]). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in the dark, the tissue was cleared in 70% ethanol.

The tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) callus bioassay was carried out as described previously (Holub et al., 1998). Six replicates were prepared for each cytokinin concentration, and the entire test was repeated twice.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

The 14-d-old Arabidopsis plants were transferred to 250-mL flasks containing 100 mL of liquid one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium, 0.1% (w/v) Suc, with or without the addition of 10 µm Phe-Ade or 10 µm 2-iP. RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR were performed as described previously (Vyroubalová et al., 2009; Mik et al., 2011). Each treatment included four biological repeats for RNA isolation. Each RNA sample was transcribed in two independent reactions, and each complementary DNA sample was run in at least two technical replicates on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the comparative cycle threshold method. The cycle threshold values were obtained by StepOne software version 2.2.2. Two household genes, ACTIN2 and SMALL NUCLEAR RIBONUCLEAR PROTEIN D1 (Quilliam et al., 2006), were used as internal standards. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Relative expression levels were calculated with DataAssist Software version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Receptor Binding and Activation Assay

The binding assays, modified from Romanov et al. (2005), were done with Escherichia coli strain KMI001 harboring the plasmid pIN-III-AHK4 or pSTV28-AHK3 (Suzuki et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001). Cultures were grown overnight in M9 minimal medium with 0.1% (w/v) casamino acids. [3H]tZ (2 nm final concentration) and different concentrations of cytokinins were added to 1-mL aliquots of culture, which were then incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the bacteria were pelleted at 13,000g for 3 min, and the pellet was suspended in 1 mL of ACS-II scintillation cocktail (Amersham Biosciences) by vortexing and sonication. The radioactivity was measured with a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter.

The receptor activation assay was described previously (Spíchal et al., 2004; Doležal et al., 2006). Briefly, cultures were grown under the same conditions as described above and diluted 1:600 before Phe-Ade or tZ was added in different concentrations. The cultures were grown further at 25°C for 16 h (AHK4) or 28 h (AHK3). Then, 5 µL of 10 mm 4-methyl-umbelliferyl-galactoside was added to 50-µL aliquots of culture, which were incubated for 20 min at 37°C; the reactions were stopped by adding 100 µL of 0.2 m Na2CO3. Fluorescence was measured using a Synergy H4 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 and 460 nm. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the remaining culture was determined, and the β-galactosidase activity was calculated as nmol 4-methylumbelliferone OD600−1 h−1.

CKX Inhibition Measurements

The production and purification of the recombinant CKX enzymes were described previously (Pertry et al., 2009; Kowalska et al., 2010). CKX activity was measured using different methods to determine the degradation of 2-iP in the presence or absence of Phe-Ade. The end-point method was modified from Frébort et al. (2002). For CKX1, CKX2, CKX5, and CKX7, the reaction mixture contained aliquots of individual CKX enzymes, 2-iP, and/or Phe-Ade in various concentrations and an electron acceptor (DCPIP or Q0) in 150 mm imidazole/HCl buffer (pH 7.5). For CKX3, 0.3 mm ferricyanide was used as an electron acceptor and the reaction was done in 100 mm imidazole/HCl buffer (pH 6.5). Consumption of 2-iP was determined spectrophotometrically as the formation of a Schiff base from 4-aminophenol and 3-methyl-2-butanal (Libreros-Minotta and Tipton, 1995) or by ultra-performance liquid chromatography (Shimadzu Nexera). For the latter, 45-µL aliquots of the reaction mixture were mixed with a 2-fold excess of ethanol immediately after starting the reaction with 2-iP or after 45 min, in triplicate for each reaction. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min, and a 5.7-fold excess of 15 mm HCOONH4, pH 4.0 (A), was added. The samples, purified through 0.22-µm nylon filters, were injected onto a C18 reverse-phase column (Zorbax RRHD Eclipse Plus, 1.8 µm, 2.1 × 50 mm; Agilent). The column was eluted with a linear gradient of A and methanol (B): 0 min, 20% B; 3 to 8 min, 100% B. The flow rate was 0.40 mL min−1, and the column temperature was 40°C. Depletion of 2-iP from the reaction mixture during the 45-min interval was subtracted from the peak areas using LabSolutions software (Shimadzu).

Finally, a continuous method was used based on bleaching of DCPIP (Laskey et al., 2003). The same reaction conditions were used as described above except that the final concentration of DCPIP was 0.03 mm. Based on DCPIP reduction rates at different concentrations of 2-iP (6–180 µm) and Phe-Ade (0.66–6.66 µm), the kinetic parameters were calculated with the software GraFit version 4.0.12.

Quantification of Endogenous Cytokinin Levels

Twenty 14-d-old Arabidopsis plants were transferred to 250-mL flasks containing 100 mL of liquid one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium, 0.1% (w/v) Suc, and 0.1% DMSO as a control or 10 µm of Phe-Ade or 2-iP. After 1 or 3 d of treatment, the plants were washed, dried on paper tissues, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Subsequently, cytokinins were extracted, purified, and analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as described previously (Pertry et al., 2010).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Optimization of the shoot regeneration protocol for high-throughput compound screening on accession C24.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phenotype of Col-0 plants and ahk double mutants grown for 1, 2, or 3 weeks in the presence or absence of 10 µm Phe-Ade or 2-iP.

Supplemental Table S1. Optimization of the shoot regeneration protocol for high-throughput compound screening on accession C24.

Supplemental Table S2. Sequences of primers used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR amplification.

Supplemental Procedures S1. Optimization of the shoot regeneration assay.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marta Greplová and Jarek Kábrt for assistance with CKX purification, Tomáš Hluska for assistance with ultra-performance liquid chromatography, and Karel Berka for predicting the docking model.

Glossary

- Phe-Ade

phenyl-adenine

- PGR

plant growth regulators

- CIM

callus induction medium

- SIM

shoot induction medium

- 2,4-D

2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- IAA

3-indoleacetic acid

- 2-iP

2-isopentenyladenine

- Col-0

Columbia

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- tZ

trans-zeatin

- DCPIP

2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol

- Q0

2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone

- BA

benzyladenine

- BM

basal medium

References

- Arata Y, Nagasawa-Iida A, Uneme H, Nakajima H, Kakimoto T, Sato R. (2010) The phenylquinazoline compound S-4893 is a non-competitive cytokinin antagonist that targets Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor CRE1 and promotes root growth in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 2047–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta R, Laurens L, Boucheron-Dubuisson E, Guivarc’h A, Carnero E, Giraudat-Pautot V, Rech P, Chriqui D. (2009) Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J 57: 626–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer C. (1996) Cytokinin inhibition of Arabidopsis root growth: an examination of genotype, cytokinin activity, and N6-benzyladenine metabolism. J Plant Growth Regul 15: 201–206 [Google Scholar]

- Banno H, Ikeda Y, Niu Q-W, Chua N-H. (2001) Overexpression of Arabidopsis ESR1 induces initiation of shoot regeneration. Plant Cell 13: 2609–2618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary AJ, Che P, Howell SH. (2002) Developmental events and shoot apical meristem gene expression patterns during shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 32: 867–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Lall S, Nettleton D, Howell SH. (2006) Gene expression programs during shoot, root, and callus development in Arabidopsis tissue culture. Plant Physiol 141: 620–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino IB, Deruère J, Kieber JJ. (2000) Characterization of the response of the Arabidopsis response regulator gene family to cytokinin. Plant Physiol 124: 1706–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuydt S, Doležal K, Van Lijsebettens M, Moritz T, Holsters M, Vereecke D. (2008) Modulation of the hormone setting by Rhodococcus fascians results in ectopic KNOX activation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 146: 1267–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rybel B, Audenaert D, Xuan W, Overvoorde P, Strader LC, Kepinski S, Hoye R, Brisbois R, Parizot B, Vanneste S, et al. (2012) A role for the root cap in root branching revealed by the non-auxin probe naxillin. Nat Chem Biol 8: 798–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doležal K, Popa I, Kryštof V, Spíchal L, Fojtíková M, Holub J, Lenobel R, Schmülling T, Strnad M. (2006) Preparation and biological activity of 6-benzylaminopurine derivatives in plants and human cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem 14: 875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclercq J, Sangwan-Norreel B, Catterou M, Sangwan RS. (2011) De novo shoot organogenesis: from art to science. Trends Plant Sci 16: 597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frébort I, Šebela M, Galuszka P, Werner T, Schmülling T, Peč P. (2002) Cytokinin oxidase/cytokinin dehydrogenase assay: optimized procedures and applications. Anal Biochem 306: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frébortová J, Galuszka P, Werner T, Schmülling T, Frébort I. (2007) Functional expression and purification of cytokinin dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis thaliana (AtCKX2) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biol Plant 51: 673–682 [Google Scholar]

- Gallois J-L, Woodward C, Reddy GV, Sablowski R. (2002) Combined SHOOT MERISTEMLESS and WUSCHEL trigger ectopic organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Development 129: 3207–3217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galuszka P, Popelková H, Werner T, Frébortová J, Pospíšilová H, Mik V, Köllmer I, Schmülling T, Frébort I. (2007) Biochemical characterization of cytokinin oxidases/dehydrogenases from Arabidopsis thaliana expressed in Nicotiana tabacum L. J Plant Growth Regul 26: 255–267 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Chickarmane VS, Ohno C, Meyerowitz EM. (2009) Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 16529–16534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Bopp M. (1968) A cytokinin test with high specificity. Planta 83: 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseloff J. (1999) GFP variants for multispectral imaging of living cells. Methods Cell Biol 58: 139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub J, Hanuš J, Hanke DE, Strnad M. (1998) Biological activity of cytokinins derived from ortho- and meta-hydroxybenzyladenine. Plant Growth Regul 26: 109–115 [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn M, Dabi T, Chory J. (2011) Structural basis for cytokinin recognition by Arabidopsis thaliana histidine kinase 4. Nat Chem Biol 7: 766–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou B, Lim E-K, Higgins GS, Bowles DJ. (2004) N-Glucosylation of cytokinins by glycosyltransferases of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 279: 47822–47832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Sheen J. (2001) Two-component circuitry in Arabidopsis cytokinin signal transduction. Nature 413: 383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu QW, Howell SH, Chua NH. (2006) The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon development. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1443–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase A, Mitsuda N, Koyama T, Hiratsu K, Kojima M, Arai T, Inoue Y, Seki M, Sakakibara H, Sugimoto K, et al (2011) The AP2/ERF transcription factor WIND1 controls cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 21: 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T. (1996) CKI1, a histidine kinase homolog implicated in cytokinin signal transduction. Science 274: 982–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska M, Galuszka P, Frébortová J, Šebela M, Béres T, Hluska T, Šmehilová M, Bilyeu KD, Frébort I. (2010) Vacuolar and cytosolic cytokinin dehydrogenases of Arabidopsis thaliana: heterologous expression, purification and properties. Phytochemistry 71: 1970–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, van der Hoorn RAL. (2011) A structural biology perspective on bioactive small molecules and their plant targets. Curr Opin Plant Biol 14: 480–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa T, Ueda N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kojima M, Nagato Y, Sakakibara H, Kyozuka J. (2007) Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445: 652–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskey JG, Patterson P, Bilyeu K, Morris RO. (2003) Rate enhancement of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase using 2,6-dichloroindophenol as an electron acceptor. Plant Growth Regul 40: 189–196 [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard M, Jürgens G, Laux T. (2002) The WUSCHEL and SHOOTMERISTEMLESS genes fulfil complementary roles in Arabidopsis shoot meristem regulation. Development 129: 3195–3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libreros-Minotta CA, Tipton PA. (1995) A colorimetric assay for cytokinin oxidase. Anal Biochem 231: 339–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Zhang SB, Lemaux PG. (2010) Toward molecular understanding of in vitro and in planta shoot organogenesis. Crit Rev Plant Sci 29: 108–122 [Google Scholar]

- Mik V, Szüčová L, Smehilová M, Zatloukal M, Doležal K, Nisler J, Grúz J, Galuszka P, Strnad M, Spíchal L. (2011) N9-substituted derivatives of kinetin: effective anti-senescence agents. Phytochemistry 72: 821–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CO. (1961) Kinetin and related compounds in plant growth. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 12: 395–408 [Google Scholar]

- Murthy BNS, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. (1998) Thidiazuron: a potent regulator of in vitro plant morphogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 34: 267–275 [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura C, Ohashi Y, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Ueguchi C. (2004) Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 1365–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernisová M, Klíma P, Horák J, Válková M, Malbeck J, Soucek P, Reichman P, Hoyerová K, Dubová J, Friml J, et al (2009) Cytokinins modulate auxin-induced organogenesis in plants via regulation of the auxin efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3609–3614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertry I, Václavíková K, Depuydt S, Galuszka P, Spíchal L, Temmerman W, Stes E, Schmülling T, Kakimoto T, Van Montagu MCE, et al. (2009) Identification of Rhodococcus fascians cytokinins and their modus operandi to reshape the plant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 929–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertry I, Václavíková K, Gemrotová M, Spíchal L, Galuszka P, Depuydt S, Temmerman W, Stes E, De Keyser A, Riefler M, et al. (2010) Rhodococcus fascians impacts plant development through the dynamic fas-mediated production of a cytokinin mix. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23: 1164–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilliam RS, Swarbrick PJ, Scholes JD, Rolfe SA. (2006) Imaging photosynthesis in wounded leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 57: 55–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov GA, Spíchal L, Lomin SN, Strnad M, Schmülling T. (2005) A live cell hormone-binding assay on transgenic bacteria expressing a eukaryotic receptor protein. Anal Biochem 347: 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaldi-Goldstein S, Baiga TJ, Pojer F, Dabi T, Butterfield C, Parry G, Santner A, Dharmasiri N, Tao Y, Estelle M, et al (2008) New auxin analogs with growth-promoting effects in intact plants reveal a chemical strategy to improve hormone delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15190–15195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens J, Torres M, Morgner M, Sacristan MD. (1993) Plant-regeneration from mesophyll-protoplasts of 4 different ecotypes and 2 marker lines from Arabidopsis thaliana using a unique protocol. Plant Cell Rep 12: 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spíchal L, Rakova NY, Riefler M, Mizuno T, Romanov GA, Strnad M, Schmülling T. (2004) Two cytokinin receptors of Arabidopsis thaliana, CRE1/AHK4 and AHK3, differ in their ligand specificity in a bacterial assay. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 1299–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spíchal L, Werner T, Popa I, Riefler M, Schmülling T, Strnad M. (2009) The purine derivative PI-55 blocks cytokinin action via receptor inhibition. FEBS J 276: 244–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Jiao YL, Meyerowitz EM. (2010) Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway. Dev Cell 18: 463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Miwa K, Ishikawa K, Yamada H, Aiba H, Mizuno T. (2001) The Arabidopsis sensor His-kinase, AHk4, can respond to cytokinins. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31: 455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens D, Van Montagu M, Van Lijsebettens M. (1988) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 5536–5540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staden J, Zazimalova E, George EF (2008) Plant growth regulators. II. Cytokinins, their analogues and antagonists. In EF George, MA Hall, GJ De Klerk, eds, Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture, Ed 3, Vol 1. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 205–226 [Google Scholar]

- Vyroubalová S, Václavíková K, Turecková V, Novák O, Smehilová M, Hluska T, Ohnoutková L, Frébort I, Galuszka P. (2009) Characterization of new maize genes putatively involved in cytokinin metabolism and their expression during osmotic stress in relation to cytokinin levels. Plant Physiol 151: 433–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ma XM, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Hou BK. (2011) N-Glucosyltransferase UGT76C2 is involved in cytokinin homeostasis and cytokinin response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 2200–2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T, Motyka V, Laucou V, Smets R, Van Onckelen H, Schmülling T. (2003) Cytokinin-deficient transgenic Arabidopsis plants show multiple developmental alterations indicating opposite functions of cytokinins in the regulation of shoot and root meristem activity. Plant Cell 15: 2532–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Suzuki T, Terada K, Takei K, Ishikawa K, Miwa K, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. (2001) The Arabidopsis AHK4 histidine kinase is a cytokinin-binding receptor that transduces cytokinin signals across the membrane. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 1017–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatloukal M, Gemrotová M, Doležal K, Havlícek L, Spíchal L, Strnad M. (2008) Novel potent inhibitors of A. thaliana cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase. Bioorg Med Chem 16: 9268–9275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. (2008) The role of local biosynthesis of auxin and cytokinin in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]