Transitory expression of high pI amylases during grain development occurs as a result of an altered hormonal environment.

Abstract

Late maturity α-amylase (LMA) is a genetic defect that is commonly found in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars and can result in commercially unacceptably high levels of α-amylase in harvest-ripe grain in the absence of rain or preharvest sprouting. This defect represents a serious problem for wheat farmers, and apart from the circumstantial evidence that gibberellins are somehow involved in the expression of LMA, the mechanisms or genes underlying LMA are unknown. In this work, we use a doubled haploid population segregating for constitutive LMA to physiologically analyze the appearance of LMA during grain development and to profile the transcriptomic and hormonal changes associated with this phenomenon. Our results show that LMA is a consequence of a very narrow and transitory peak of expression of genes encoding high-isoelectric point α-amylase during grain development and that the LMA phenotype seems to be a partial or incomplete gibberellin response emerging from a strongly altered hormonal environment.

Late maturity α-amylase (LMA), also known as prematurity α-amylase, is a genetic defect that is widespread in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) germplasm and can result in unacceptably high levels of α-amylase in harvest-ripe grain in the absence of rain or preharvest sprouting (Mares and Mrva, 2008a). The defect is inherited as a recessive trait (Mrva and Mares, 1996a) and is associated with a highly significant quantitative trait locus (QTL) on the long arm of chromosome 7B and a number of QTLs of lesser significance (Mrva and Mares, 2001b; Mares and Mrva, 2008a; Mrva et al., 2008; Emebiri et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2010). In tall genotypes suffering from LMA, the expression of LMA is constitutive. In contrast, in the presence of semidwarfing (GA-insensitive) genes such as Reduced Height1 (Rht1) or Rht2, LMA expression is reduced (Mrva and Mares, 1996b), highly variable, and appears to be dependent on a cool temperature shock during the middle stages of grain development (Mrva and Mares, 2001a; Farrell and Kettlewell, 2008; Mares and Mrva, 2008a). In both cases, LMA is a consequence of the synthesis of high-pI α-amylase coded by the α-Amylase1 (α-Amy1) genes on wheat chromosomes 6A, 6B, and 6D.

High-pI α-amylase is also synthesized following germination, and, together with the inhibitory effects of the GA insensitivity gene, these factors suggest that GA is involved in the expression of LMA. However, while there are some points of similarity between α-amylase production in germination and LMA, there are a number of differences (Mrva et al., 2006; Mares and Mrva, 2008a). In germinated grain, α-amylase is synthesized by the scutellum and later by the adjacent aleurone, the latter under the influence of GA produced by the embryo. With time, α-amylase synthesis spreads toward the distal end of the grain. In contrast, there is no evidence for the involvement of the embryo, or embryo-derived GA, in LMA, and the enzyme is distributed approximately equally between proximal and distal halves of the grains. Similarly, whereas germinating grains can synthesize large amounts of α-amylase according to an exponential rate curve, the synthesis of α-amylase in LMA-affected grains rarely exceeds the amount typical of the early stages of germination. The amount can be sufficient, however, to exceed grain receival standards and result in the downgrading of quality (Mares and Mrva, 2008a).

Apart from the circumstantial evidence that GA is somehow involved in the expression of LMA, the mechanisms or genes underlying LMA are unknown. GA control of gene expression in mature aleurone has been extensively studied, and it remains to be determined whether similar response pathways are active in LMA-affected grains during grain development. We have developed sets of doubled haploid lines derived from the same cross, cv Spica × Maringa, expressing constitutive LMA (+LMA) or not expressing LMA (–LMA), and we have examined the expression patterns for a number of genes, including those encoding α-amylases, characteristic of GA-treated aleurone, and enzymes involved in the synthesis and catabolism of the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA), over the period of grain development where α-amylase is detected. Second, we used targeted microarrays to identify genes that are up-regulated in +LMA or –LMA genotypes during the initiation of high-pI α-amylase synthesis. Finally, we compared the hormonal profile of +LMA and –LMA developing grains. These techniques were used to probe a very narrow and transitory peak of expression of genes encoding high-pI α-amylase that is responsible for the LMA phenotype and indicate that the LMA phenotype seems to be a partial or incomplete GA response emerging from a strongly altered hormonal environment.

RESULTS

Grain Development and the Synthesis of α-Amylase

Doubled haploid genotypes with and without constitutive LMA were grown side by side under the same experimental conditions. Anthesis to harvest ripeness (12% grain moisture) was completed in 45 d in all of the lines examined. Grain moisture declined gradually from around 70% (moisture as a percentage of fresh weight) at 12 DPA to around 45% by 35 DPA and then more rapidly over the ensuing 10 d (Fig. 1). Maximum grain dry weight was achieved by 32 to 35 DPA (data not shown). Grain development as judged by physical appearance appeared to be similar in +LMA and –LMA genotypes (Fig. 2). Thirty-two DPA grains from a +LMA and a –LMA genotype were imbibed, sectioned, and stained, and aleurone cells were observed with a microscope. About 500 aleurone cells from each genotype were examined, but no visual differences were observed that could be associated with LMA (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Changes in grain moisture during grain development in +LMA and –LMA genotypes.

Figure 2.

Grain appearance for –LMA genotype cv Spica × Maringa line 47 (Sp/M#47; top row) and +LMA genotype cv Spica × Maringa line 52 (Sp/M#52; bottom row) at intervals during development.

High-pI α-amylase protein remained low or below the level of detection until 20 DPA, increased rapidly in the +LMA genotypes, reaching a maximum at 32 to 35 DPA, and then remained at this level through to harvest ripeness (Fig. 3). Samples with elevated high-pI α-amylase protein (measured by ELISA) also had high total α-amylase activity measured either with the Amylazyme assay or with Falling Number (data not shown). Grain moisture content corresponding to the time of initiation of synthesis of α-amylase was 55% to 60%, and grains were just starting to develop a tinge of yellow.

Figure 3.

Changes in grain high-pI α-amylase protein content in +LMA and –LMA genotypes during grain development measured by ELISA. Eight technical replicates were performed. Error bars represent se. OD, Optical density.

Expression of α-Amylase Genes and GA Response Genes in Mature Aleurone

In order to study which genes encoding α-amylase were involved in the expression of LMA, specific primers (Supplemental Table S1) were designed for high pI (α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2), low pI (α-Amy2-1), and other known members (α-Amy3-1 and α-Amy4-1) of this family of genes for quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. As a starting point, the effect of exogenous GA on the expression of α-Amy genes in mature aleurone from a control wheat variety was investigated. Aleurone layers from mature wheat grains were harvested and imbibed in control medium or in medium supplemented with 1 µm GA. After 24 h of imbibition, RNA was extracted and complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized. The expression of all α-Amy genes was very low in aleurone imbibed in control medium, but in the GA treatment, the expression of α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2 was dramatically induced (Fig. 4A). α-Amy2-1 was also induced by GA but to a lower extent, while the expression of α-Amy3-1 and α-Amy4-1 was not affected (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

GA induction of the α-Amy genes (A), of several GA-responsive genes (B), and of several ABA metabolic genes (C) in mature aleurone layers isolated from grains imbibed in control medium or in the presence of GA. Three biological replicates were performed. Error bars represent se.

The expression of other known cereal GA response genes, including GAMYB, a transcription regulator of GA signaling in aleurone (Gubler et al., 1995, 1999; Murray et al., 2006), a cell wall-degrading enzyme, (1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase (Mundy and Fincher, 1986), and two proteases, triticain-α and triticain-γ (Kiyosaki et al., 2009), was also determined in mature aleurone. In comparison with the expression on control medium, the expression of (1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase was induced 5-fold by GA, triticain-α was induced 14-fold, triticain-γ was induced 32-fold, and GAMYB was induced 3-fold (Fig. 4B).

We also studied the effect of GA over several ABA metabolic wheat genes (NCED1, ABA8′OH-1, and ABA8′OH-2; Ji et al., 2011). The ABA biosynthetic gene NCED1 and the ABA catabolic gene ABA8′OH-2 were not significantly affected by GA, although the gene ABA8′OH-1 was induced nearly 4-fold by GA (Fig. 4C).

α-Amy Gene Expression in +LMA and –LMA Genotypes during Grain Development

The next stage was to determine which α-Amy genes were involved in LMA and whether the gene expression pattern was similar to the pattern that we found in mature aleurone challenged with GA. The expression patterns of the α-Amy genes, therefore, were analyzed during grain development in +LMA and –LMA genotypes. Based on the α-amylase protein profiling of +LMA and –LMA genotypes (Fig. 3), four developmental time points were selected for gene expression studies. Aleurone layers were isolated from developing grains at 17 DPA (no α-amylase detected), at 20 DPA (just before α-amylase appears in +LMA genotypes), at 23 DPA (as α-amylase increases in +LMA), and at 26 DPA (as α-amylase increases further in +LMA). As an indicator of developmental stage, in this experiment, 17, 20, 23, and 26 DPA corresponded to thermal times of 190, 225, 255, and 290 degree days from anthesis (see “Materials and Methods”). At 17 DPA, the expression of α-Amy1-1, α-Amy1-2, α-Amy2-1, and α-Amy3-1 was very low, and no differences were observed between +LMA and –LMA genotypes. The expression of α-Amy4-1 was higher, but no differences between lines were detected (Fig. 5A). At 20 DPA, the expression profile was almost identical to 17 DPA (Fig. 5B). At 23 DPA, α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2 were clearly induced in three of the +LMA lines (25, 127, and 52) and remained very low in the other genotypes (Fig. 5C). The expression of α-Amy2-1, α-Amy3-1, and α-Amy4-1 did not change in comparison with the previous time points. At 26 DPA, α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2 expression was still high in two of the +LMA lines (127 and 52), and α-Amy2-1, α-Amy3-1, and α-Amy4-1 showed the same expression levels as previously (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, at 26 DPA in line 52, the expression of α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2 was much higher than at 23 DPA, and in line 25, the expression of these genes at 26 DPA was back to base levels. These results highlight the transient nature of the expression of α-Amy genes in +LMA genotypes, which only last for around 1 to 4 d. This short α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2 expression window could also explain the inability to detect α-Amy1 gene expression in line 131 despite ELISA data that showed high levels of amylase protein in that line. No α-Amy1 gene expression was detected in this line at 23 and 26 DPA, but it may have been detected if samples had been collected within the intervals between 20 to 23 DPA.

Figure 5.

Analysis of α-Amy gene expression in aleurone isolated from +LMA and –LMA genotypes at intervals during grain development. Three replicates were performed. Error bars represent se.

Expression of GA Response and ABA Metabolic Genes in +LMA and –LMA Genotypes

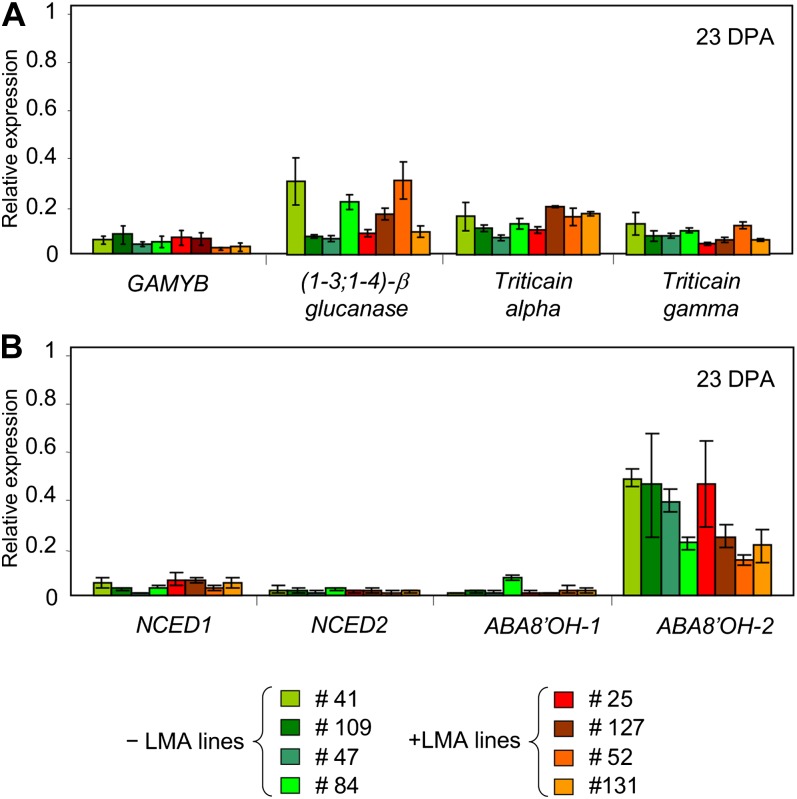

In the same set of +LMA and –LMA samples, the expression of four control GA-responsive genes [GAMYB, (1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase, triticain-α, and triticain-γ] was also analyzed in order to compare with the response found in mature aleurone. These genes were clearly induced by GA in mature aleurone (Fig. 4B); however, no increase in their expression in +LMA genotypes during grain development was detected. The expression levels of those GA-responsive genes were very similar between +LMA and –LMA genotypes and did not change between 17 and 26 DPA (data not shown). As an example, their relative expression at 23 DPA is shown in Figure 6A.

Figure 6.

Expression of GA-responsive (A) and ABA metabolic (B) genes in developing aleurone isolated from +LMA and –LMA genotypes at 23 DPA. Three replicates were performed. Error bars represent se.

Whether the LMA phenotype could be altering the expression of two important ABA biosynthetic genes (NCED1 and NCED2; Ji et al., 2011) and two ABA catabolic genes (ABA8′OH-1 and ABA8′OH-2; Ji et al., 2011) was also investigated. No evidence of differential expression between +LMA and –LMA genotypes during grain development was detected at any time point. Again, results from 23 DPA are shown as an example (Fig. 6B).

Microarray Analysis of Gene Expression in Aleurone of +LMA and –LMA Genotypes

A global gene expression analysis using the Agilent 44K microarray was used to genetically profile the LMA phenotype. We did not find probes matching the wheat α-Amy genes in the microarray, but we wanted to find other genes associated with LMA. Gene expression in three +LMA lines (25, 127, and 52) and in three –LMA lines (41, 109, and 47) was studied at 20 DPA (before any α-amylase protein is detectable; Fig. 3) and at 23 DPA (when α-amylase protein is first observed). For the microarray analysis, each of the three doubled haploid lines in the +LMA or the –LMA group was treated as a biological replicate. First, probes with ±2-fold change between +LMA and –LMA groups and P < 0.01 were considered. Using those cutoff criteria, only 37 probes were identified as differentially expressed at 20 and/or 23 DPA. Then, and thinking that only a very reduced proportion of aleurone cells in an LMA variety express LMA (about 2%; Mrva et al., 2006), we decided to use less stringent criteria to avoid the effects of possible gene expression dilution. So probes with ±1.5-fold change between +LMA and –LMA groups and P < 0.01 were considered. Eighty-three probes satisfied the cutoff criteria at 20 and/or 23 DPA: 56 of them were up-regulated in the +LMA genotypes (Table I) and 27 were up-regulated in the –LMA genotypes (Table II). Three probes from Table I and three probes from Table II were selected for validation by qRT-PCR, and the results obtained were very similar to those found by the microarray analysis (Supplemental Fig. S2). The normalized expression values for all the probes in all samples are given in Supplemental Table S2.

Table I. Probes up-regulated in +LMA lines.

Fifty-six probes were significantly overexpressed in the +LMA lines more than 1.5-fold (highlighted in boldface) at 20 and/or at 23 DPA.

| Probe Name | Probe Identifier | Fold Change |

P | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 DAA | 23 DAA | ||||

| A_99_P239876 | TA64425_4565 | 5.58 | 2.70 | 3.4E-10 | Os05g0592600 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (15%) [TC317164]; Initiation factor2 family protein |

| A_99_P490267 | TC334665 | 5.34 | 3.15 | 9.0E-09 | Unknown |

| A_99_P433057 | TC299231 | 4.01 | 2.38 | 2.1E-08 | Unknown |

| A_99_P241121 | TA64772_4565 | 3.52 | 2.26 | 2.3E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P241126 | CK207885 | 3.21 | 2.04 | 7.0E-03 | Wheat Functional Genomics of Abiotic Stress (FGAS) Project: Library 5 Gate 7 wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [CK207885] |

| A_99_P229111 | TA61320_4565 | 3.05 | 2.49 | 4.9E-08 | Predicted protein; Ostreococcus lucimarinus, partial (6%) [TC289607] |

| A_99_P230131 | TA61561_4565 | 3.02 | 2.33 | 2.4E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P217041 | TA57043_4565 | 2.48 | 6.17 | 5.0E-04 | Wheat cDNA, clone: SET3_D18, cv Chinese Spring |

| A_99_P231166 | TA61862_4565 | 2.37 | 1.82 | 2.7E-06 | Unknown |

| A_99_P229201 | TA61342_4565 | 2.33 | 1.99 | 2.5E-08 | Predicted protein; Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, partial (3%) [TC285456] |

| A_99_P484557 | TA57006_4565 | 2.30 | 5.66 | 1.3E-04 | Wali6 protein; wheat, partial (85%) [TC331873] |

| A_99_P383537 | TA106400_4565 | 2.27 | 1.81 | 8.1E-08 | Polysaccharide deacetylase precursor; Pseudomonas putida, partial (5%) [TC302730] |

| A_99_P306396 | TA83585_4565 | 2.13 | 1.58 | 5.8E-07 | TolA protein; Vibrionales sp. bacterium, partial (13%) [TC285028] |

| A_99_P488392 | TC333744 | 2.09 | 1.63 | 6.2E-08 | Possible Ribosomal L29e protein family; Synechococcus sp., partial (12%) [TC333744] |

| A_99_P217741 | TA57367_4565 | 2.06 | 1.51 | 6.5E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P461432 | TC319251 | 2.04 | 1.57 | 3.1E-03 | Chromosome chr18 scaffold_1, whole-genome shotgun sequence; grape (Vitis vinifera), partial (29%) [TC319251] |

| A_99_P289376 | TA78618_4565 | 2.03 | 1.31 | 7.3E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P277691 | TA75212_4565 | 2.00 | 1.55 | 2.1E-08 | Unknown |

| A_99_P244466 | TA65608_4565 | 1.98 | 1.38 | 6.4E-07 | Wheat cDNA, clone: WT011_H23, cv Chinese Spring |

| A_99_P534342 | TC353270 | 1.94 | 1.40 | 3.4E-09 | Unknown |

| A_99_P429037 | TC296078 | 1.92 | 1.50 | 2.9E-05 | PE-PGRS family protein; Mycobacterium tuberculosis, partial (4%) [TC296078] |

| A_99_P557882 | TC361978 | 1.90 | 1.43 | 4.6E-04 | Monosaccharide transporter6; rice ssp. japonica, partial (8%) [TC361978] |

| A_99_P457092 | DN829647 | 1.82 | 1.51 | 1.1E-03 | cDNA library; wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [DN829647] |

| A_99_P462667 | TC319988 | 1.82 | 4.59 | 6.5E-05 | Wali3 protein; wheat, partial (81%) [TC319988] |

| A_99_P293411 | TA79766_4565 | 1.79 | 1.27 | 6.9E-03 | Fasciclin-like protein FLA1; wheat, partial (10%) [TC335892] |

| A_99_P236421 | TA63445_4565 | 1.79 | 1.80 | 2.6E-03 | Wali5 protein; wheat, complete [TC306694] |

| A_99_P236391 | TA63438_4565 | 1.76 | 1.50 | 2.9E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P543232 | TA63453_4565 | 1.76 | 1.63 | 3.4E-03 | Wali5 protein; wheat, partial (34%) [TC356640] |

| A_99_P236411 | TA63442_4565 | 1.75 | 1.52 | 1.8E-03 | Wali5 protein; wheat, partial (34%) [TC356640] |

| A_99_P236486 | TA63458_4565 | 1.75 | 1.61 | 1.8E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P419937 | TC289170 | 1.74 | 1.94 | 7.9E-04 | Os04g0639200 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (38%) [TC289170] |

| A_99_P519152 | CK161960 | 1.71 | 1.49 | 3.9E-03 | Wheat FGAS: Library 4 Gate 8 wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [CK161960] |

| A_99_P286731 | TA77840_4565 | 1.70 | 1.21 | 7.8E-04 | Programmed cell death protein2, C-terminal domain-containing protein, expressed; rice ssp. japonica, partial (32%) [TC295481] |

| A_99_P421652 | TC290507 | 1.69 | 1.33 | 2.3E-07 | Predicted protein; Monosiga brevicollis, partial (3%) [TC290507] |

| A_99_P251481 | TA67572_4565 | 1.68 | 1.49 | 6.8E-03 | Chromosome chr18 scaffold_1, whole-genome shotgun sequence; grape, partial (63%) [TC337280] |

| A_99_P278691 | TA75509_4565 | 1.67 | 1.16 | 4.8E-03 | Os09g0552400 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (18%) [TC332503]. RmlC-like cupin family protein |

| A_99_P495327 | TC336890 | 1.67 | 1.12 | 6.2E-03 | Ribonucleotide reductase, barrel domain; Burkholderia thailandensis, partial (3%) [TC336890] |

| A_99_P442867 | TC306694 | 1.66 | 1.54 | 5.9E-03 | Wali5 protein; wheat, complete [TC306694] |

| A_99_P216921 | TA57006_4565 | 1.64 | 3.55 | 9.1E-05 | Wali6 protein; wheat, partial (80%) [TC332871] |

| A_99_P236461 | TA63453_4565 | 1.64 | 1.55 | 3.7E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P236451 | TA63451_4565 | 1.63 | 1.55 | 5.4E-03 | Wali5 protein; wheat, complete [TC319425] |

| A_99_P124250 | CN012056 | 1.63 | 1.20 | 2.3E-03 | Wheat Fusarium graminearum-infected spike cDNA library, mRNA sequence [CN012056] |

| A_99_P244556 | TA65629_4565 | 1.61 | 1.28 | 3.3E-03 | Nuclease I; barley, partial (77%) [TC288687] |

| A_99_P236491 | TA63459_4565 | 1.61 | 1.62 | 7.3E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P543167 | CK161960 | 1.60 | 1.41 | 4.7E-03 | Wheat FGAS: Library 4 Gate 8 wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [CK161960] |

| A_99_P415582 | TC285524 | 1.57 | 1.32 | 3.5E-06 | Unknown |

| A_99_P329196 | TA90299_4565 | 1.57 | 1.48 | 4.1E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P255741 | TA68758_4565 | 1.55 | −1.02 | 6.7E-03 | Cupin family protein, expressed; rice ssp. japonica, partial (4%) [TC337126] |

| A_99_P394452 | TA109072_4565 | 1.51 | 1.33 | 4.7E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P236396 | CK161960 | 1.51 | 1.42 | 4.8E-03 | Wheat FGAS: Library 4 Gate 8 wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [CK161960] |

| A_99_P218621 | TA57596_4565 | 1.48 | 1.65 | 2.9E-03 | ABA-inducible protein WRAB1; wheat, complete [TC288919] |

| A_99_P245726 | TA65929_4565 | 1.35 | 2.37 | 5.3E-04 | Pathogenesis-related protein1.1 precursor; wheat, complete [TC285151] |

| A_99_P265761 | TA71620_4565 | 1.28 | 1.80 | 1.9E-03 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase; Musa acuminata, partial (21%) [TC329070] |

| A_99_P213376 | TA55414_4565 | 1.24 | 1.76 | 5.2E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P469557 | DN829463 | 1.13 | 1.53 | 1.1E-03 | cDNA library wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [DN829463] |

| A_99_P470812 | TA86664_4565 | −1.01 | 1.55 | 2.0E-03 | 1,4-β-d-Mannan endohydrolase; barley var distichum, partial (33%) [TC324673] |

Table II. Probes up-regulated in –LMA lines.

Twenty-seven probes were overexpressed in the –LMA lines more than 1.5-fold (highlighted in boldface) at 20 and/or at 23 DPA.

| Probe Name | Probe Identifier | Fold Change |

P | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 DAA | 23 DAA | ||||

| A_99_P142933 | CJ929649 | 44.60 | 10.02 | 3.6E-09 | Y. Ogihara unpublished cDNA library; wheat cDNA clone whchan3h03 5′, mRNA sequence [CJ929649] |

| A_99_P224251 | TA59797_4565 | 5.02 | 4.51 | 8.5E-03 | Wheat ribosomal protein L17 mRNA, complete coding sequence |

| A_99_P153962 | CJ926746 | 3.84 | 2.48 | 2.5E-10 | Y. Ogihara unpublished cDNA library, wheat cDNA clone whchan30p15 5′, mRNA sequence [CJ926746] |

| A_99_P230121 | TA61559_4565 | 3.08 | 2.48 | 2.7E-03 | γ-Thionin; barley, partial (98%) [TC336410] |

| A_99_P407792 | TA63249_4565 | 2.88 | 2.15 | 1.0E-09 | Os10g0397400 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (76%) [TC278422]; cell elongation protein DIMINUTO |

| A_99_P448897 | TC310916 | 2.65 | 1.80 | 5.1E-07 | Unknown |

| A_99_P287416 | TA78047_4565 | 2.56 | 1.76 | 5.6E-08 | Os03g0848200 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (40%) [TC320092]; phytase |

| A_99_P434382 | TA60205_4565 | 2.31 | 1.72 | 9.8E-03 | 40S ribosomal protein S15a-1; Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), complete [TC300266] |

| A_99_P443517 | TC307152 | 2.21 | 1.82 | 2.5E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P208196 | TA53518_4565 | 2.18 | 1.35 | 7.6E-04 | Unknown |

| A_99_P363836 | TA101312_4565 | 2.17 | 1.82 | 4.1E-03 | CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3; Petunia hybrida, partial (26%) [TC307683] |

| A_99_P210321 | TA54232_4565 | 2.14 | 1.32 | 7.8E-03 | Ferredoxin-NADP(H) oxidoreductase; wheat, partial (10%) [TC336047] |

| A_99_P215456 | TA56293_4565 | 2.14 | 1.55 | 1.1E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P215306 | TA56235_4565 | 2.05 | 1.44 | 5.6E-03 | Probable conjugal transfer protein; Caulobacter sp., partial (4%) [TC315249] |

| A_99_P215471 | TA56315_4565 | 1.97 | 1.59 | 6.1E-04 | Unknown |

| A_99_P427842 | TC295283 | 1.91 | 1.65 | 9.5E-09 | Wheat cDNA, clone: SET4_C16, cv Chinese Spring |

| A_99_P198871 | TA50571_4565 | 1.87 | 1.59 | 2.4E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P201276 | TA51341_4565 | 1.75 | 1.17 | 8.0E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P260276 | TA70074_4565 | 1.74 | 1.58 | 7.0E-04 | Os05g0595300 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (21%) [TC350416]; CCT domain-containing protein |

| A_99_P104810 | CK159501 | 1.73 | 1.87 | 4.3E-03 | Wheat FGAS: TaLt5 wheat cDNA, mRNA sequence [CK159501] |

| A_99_P225791 | TA60205_4565 | 1.71 | 1.44 | 5.6E-03 | 40S ribosomal protein S15a-1; Arabidopsis, partial (77%) [TC354179] |

| A_99_P260256 | TA70070_4565 | 1.69 | 1.58 | 7.2E-04 | Os05g0595300 protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (19%) [TC307377]; CCT domain-containing protein |

| A_99_P462517 | TA103921_4565 | 1.59 | 1.23 | 3.3E-03 | Calcineurin B-like protein; rice ssp. japonica, partial (11%) [TC319899] |

| A_99_P251506 | TA67578_4565 | 1.54 | 1.31 | 6.6E-03 | Unknown |

| A_99_P260606 | TA70166_4565 | 1.52 | 1.09 | 5.0E-04 | Type IV pilus assembly PilZ; Acidothermus cellulolyticus, partial (9%) [TC302599] |

| A_99_P498137 | TA52414_4565 | 1.39 | 1.52 | 4.0E-03 | Manganese superoxide dismutase; wheat, partial (68%) [TC338095] |

| A_99_P269046 | TA72621_4565 | 1.38 | 1.50 | 1.6E-04 | CTV.22; Poncirus trifoliata, partial (15%) [TC299309] |

Out of the 56 probes up-regulated in the +LMA genotypes (Table I), 50 were found at 20 DPA, 36 at 23 DPA, and 30 at both developmental points. Seventeen of those probes are annotated as “unknown,” and the majority of the rest show very little similarity with known proteins. The probe A_99_P239876 showed the bigger fold change at 20 DPA (5.58-fold) and shows similarity with a member of the Translational initiation factor2 family. This probe had a 2.70-fold change at 23 DPA. Several other probes had a similar expression pattern, showing a bigger fold change at 20 DPA than at 23 DPA, but few of these are annotated. The probes A_99_P286731 (Programmed cell death protein2) and A_99_P244556 (NucleaseI) followed that trend and are well annotated. Another group of probes displayed a bigger fold change at 23 DPA than at 20 DPA. From this group, three different probes were annotated as Wali proteins (for wheat aluminum-induced proteins; Snowden et al., 1995). Probes A_99_P484557 and A_99_P216921 (Wali6) were up-regulated 2.30- and 1.64-fold at 20 DPA and 5.66- and 3.55-fold at 23 DPA, respectively. The probe A_99_P462667 (Wali3) was up-regulated 1.82-fold at 20 DPA and 4.59-fold at 23 DPA. Five other probes were annotated as Wali5 proteins, and they have similar fold change at both 20 and 23 DPA. The ABA-inducible protein WRAB1 (probe A_99_P218621), the Pathogenesis-related protein1.1 precursor (A_99_245726), a Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (A_99_P265761), and a 1,4-β-d-mannan endohydrolase (A_99_P470812) also displayed higher fold change at 23 DPA than at 20 DPA.

On the other hand, out of the 27 probes up-regulated in the –LMA genotypes (Table II), 25 were found at 20 DPA, 19 at 23 DPA, and 17 at both developmental points. Again, many probes were poorly annotated, and eight of them were classified as unknown. The probe A_99_P142933 was found to be strongly up-regulated at 20 DPA (44.60-fold change) and also at 23 DPA (10.02-fold change). This probe matched a wheat cDNA with no similarity to known sequences. The second most highly up-regulated probe by LMA (A_99_P224251) encodes a wheat ribosomal protein and is up-regulated 5.02- and 4.51-fold at 20 and 23 DPA, respectively. The third probe (A_99_P153962) in this group does not shown homology to known genes. The fourth probe (A_99_P230121) encoded a γ-thionin protein and was up-regulated 3.08- and 2.48-fold at 20 and 23 DPA, respectively. The fifth probe (A_99_P407792) showed 76% similarity with the rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic gene Diminuto and was up-regulated 2.88- and 2.15-fold at 20 and 23 DPA, respectively. From the rest of the list, the probe A_99_P498137 matched a manganese superoxide dismutase and was 1.52-fold up-regulated at 23 DPA in –LMA lines.

Expression of LMA-Altered Genes in GA-Treated Mature Aleurone

To test if some of the genes found to be altered by LMA were also induced or repressed in mature aleurone after the GA treatment, primers were developed for three putative Wali genes (A_99_P462667, A_99_P484557, and A_99_P236421) up-regulated in +LMA genotypes during grain development and for three probes (A_99_P142933, A_99_P224251, and A_99_P407792) that were up-regulated in –LMA genotypes (the differential expression of all those genes was validated by qRT-PCR; Supplemental Fig. S2). Expression of those genes was studied by qRT-PCR in mature aleurone challenged with GA (Fig. 7). The expression of two out of three genes up-regulated in +LMA was shown to be actually repressed by GA in mature aleurone, and the other one was not detected in mature aleurone (Fig. 7A). The expression of the three genes up-regulated by –LMA was either not significantly affected by GA or was not detected in mature aleurone (Fig. 7B). This result shows a different gene expression signature in LMA-affected developing aleurone and in mature aleurone treated with GA.

Figure 7.

Expression in GA-treated mature aleurone of some LMA-affected genes. The expression of three LMA up-regulated genes (A) and three LMA down-regulated genes (B) was studied. Three biological replicates were performed. Error bars represent se. nd, Not detected.

Hormone Profiling of LMA

Deembryonated developing grains (endosperm, testa, and pericarp) from three +LMA and three –LMA genotypes at 23 DPA were isolated for hormone quantification. Several ABA-related compounds (neo-phaseic acid, 7′-hydroxy-ABA, phaseic acid, dihydrophaseic acid, and cis- and trans-ABA), auxins (indole-3-acetic acid [IAA], indole-3-butyric acid, IAA-Asp, IAA-Glu, IAA-Ala, and IAA-Leu), cytokinins (cis- and trans-zeatin, cis- and trans-zeatin riboside, cis- and trans-zeatin-O-glucoside, dihydrozeatin, dihydrozeatin riboside, isopentenyladenine, and isopentenyladenosine riboside), and GAs (GA1, GA3, GA4, GA7, GA8, GA9, GA19, GA20, GA24, GA29, GA34, GA44, GA51, and GA53) were assayed, and their endogenous levels and full names are given in Supplemental Table S3. Compounds that were detected and quantifiable are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Hormonal analysis of LMA and non-LMA grains. ABA, GAs, auxins, and cytokinins were quantified in deembryonated half-grains isolated at 23 DPA. Two technical replicates per sample were assayed. For details, see Supplemental Table S3.

Major changes in some hormones between the two sets of genotypes tested were observed. First, the ABA content was about 2-fold higher in +LMA (about 200 ng g−1 dry weight) than in –LMA samples (about 100 ng g−1 dry weight; Fig. 8A). In addition, several GAs were more abundant in +LMA than in –LMA samples; in particular, GA19 was about 20-fold more abundant (Fig. 8B). By comparison, auxin (IAA) was clearly more abundant in –LMA than in +LMA (20,000 versus 5,000 ng g−1 dry weight; Fig. 8C), while cytokinins were not significantly altered (Fig. 8D).

These results show a deeply altered hormone profile in developing +LMA grains and suggest that, in LMA genotypes, the mechanisms controlling hormone homeostasis are altered. As an indirect indicator of the ratio of GA to ABA (which is critical in many plant processes, including germination), it is worth noting that the ratio of GA19 to ABA appeared to be about 10 times higher in +LMA than in –LMA developing grains.

DISCUSSION

Grain Development and Expression of LMA

Even when LMA-affected grains are visually and anatomically identical to LMA-free grains, we have shown by detailed analysis that LMA represents a significant deviation from the normal pattern of events in grain development in wheat. Why and how the changes in hormone levels and gene expression are mainly buffered so grains appear anatomically similar is intriguing. LMA has not been found so far in Aegilops tauschii (DD genome) or Triticum monococcum (AmAm genome; D.J. Mares and K. Mrva, unpublished data). On the other hand, relatively high frequencies of LMA in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum durum; AABB genome), in synthetic hexaploid wheat (T. turgidum durum × A. tauschii), and of course in bread wheat (AABBDD) have been reported (Mares and Mrva, 2008b). That suggests that LMA seems to be a syndrome introduced during wheat domestication and breeding rather than a common phenomenon found in other crop cereals or undomesticated wheat ancestors.

Typically, low-pI (α-Amy2) α-amylase synthesized in the pericarp of grains shortly after anthesis disappears rapidly as the grain matures, and there is no further synthesis of any α-amylase unless rain falls on the ripe crop and induces sprouting (Mares and Gale, 1990). The results reported here not only confirm the synthesis of high-pI α-amylase in +LMA genotypes during grain development but place this brief period of enzyme synthesis precisely in relation to changes in grain moisture, dry weight, and appearance. The period in grain development when LMA is expressed appears to coincide with other important changes within the developing grain, notably the decline in GA and rise in ABA as well as the onset of grain dehydration commencing with the seed coat. The aleurone of developing grain is capable of producing α-amylase if challenged with exogenous GA, but only if the grain is first dried artificially (King, 1976; Armstrong et al., 1982; Jiang et al., 1996). Gale and Lenton (1987) failed to detect a peak of new GA synthesis preceding LMA expression. An alternative explanation is that LMA may represent a loss of function of a gene or genes that normally inhibit the capability of the aleurone of developing grains to respond to GA and that for a short period there is sufficient endogenous GA to trigger α-Amy1 gene expression. Consistent with this proposal, previous reports for wheat, barley (Hordeum vulgare), and rice (Oryza sativa) indicate that the synthesis of GA precedes that of ABA during grain development but that the phases of synthesis overlap (King, 1976; Radley, 1979; Mounla et al., 1980; Yang et al., 2003; Eradatmand et al., 2011).

Genetic Characterization of the α-Amylase Response to GA in Mature Aleurone

It is well established that in the mature cereal aleurone, GA triggers a series of events that are characterized by the synthesis and secretion of several hydrolytic enzymes (α-amylase, glucanases, proteases, etc.) driven by the GAMYB transcription factor (Murray et al., 2006) and that lead to the degradation of the endosperm and finally to programmed cell death (PCD) in the aleurone (Fath et al., 2000). In order to compare at the genetic level the typical α-amylase production in the mature aleurone with the abnormal production during LMA in developing aleurone, the genetic response to added GA in mature aleurone was first characterized. The results for GA-treated mature aleurone confirmed that the genes encoding high-pI α-amylase (α-Amy1-1 and α-Amy1-2) are strongly induced after the GA treatment, whereas genes encoding other α-amylases are lowly expressed (α-Amy2-1 and α-Amy3-1) or not induced (α-Amy4-1). In addition to the α-Amy1 genes, genes encoding the wheat GAMYB transcription factor, a glucanase [(1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase], and two proteases (triticain-α and triticain-γ) were also clearly induced by the treatment in mature aleurone, as expected. There was also evidence of a cross-talk response between GA and ABA, as we found the up-regulation of the ABA catabolic gene ABA8′OH-1 in the GA-treated aleurone, which possibly could lead to a decrease in ABA concentration.

Genetic Characterization of the α-Amylase Response during LMA

Abnormal production of α-amylase in +LMA genotypes has been well characterized at the enzymatic and cellular levels. Previous studies have shown that high-pI α-amylase is produced in small pockets of cells randomly distributed across the aleurone layer during a particular developmental window (Mrva et al., 2006). We failed to find any anatomical differences between aleurone cells from a constitutive +LMA genotype and a –LMA genotype, although this may have been due to a failure to section affected cells previously shown to be sparsely distributed in the aleurone (Mrva et al., 2006). However, what our anatomical studies show is that aleurone cells from +LMA and –LMA genotypes are at a similar developmental stage when LMA appears.

The results reported here suggest that the genetic signature of LMA expression is similar to that of GA-treated mature aleurone only in the expression of the α-Amy1 genes. Expression of these genes coincided with the appearance of high-pI α-amylase protein at 23 and 26 DPA in +LMA but not in –LMA genotypes. Unlike GA-treated aleurone, no expression of other GA-regulated genes like GAMYB, glucanase, or protease genes was detected. Lazarus et al. (1985) reported that the pattern of α-Amy1 mRNA accumulation in wheat aleurone resembled that of nonamylase genes regulated by GA. In this context, the LMA phenotype appears to be a partial or incomplete GA response. Baulcombe and Buffard (1983) noted, however, that α-Amy mRNA was by far the most abundant species in tissue incubated with GA. It is possible that the overall level of gene expression in LMA-affected aleurone tissue is so much reduced compared with GA-treated mature aleurone that transcripts of other GA-regulated genes are below the level of detection.

These results confirm that high-pI α-amylases are the enzymes involved in the LMA phenomenon. An interesting observation is that the induction of the α-Amy1 genes in the +LMA samples appeared to be transitory in nature over a very narrow time frame. The induction of the α-Amy1 genes only persisted for between 1 and 4 d. This is consistent with an early study by Lazarus et al. (1985) that reported that mRNA accumulation commenced 6 to 12 h after the start of incubation with GA, reaching a peak at 24 h, except for α-Amy mRNA, which declined after 48 h. The transient expression is also consistent with observations that high-pI α-amylase protein increases rapidly during the middle stages of grain development in LMA genotypes but then plateaus at a level that is relatively low compared with GA-challenged aleurone or germination. Nevertheless, there can still be unacceptably high levels of activity at harvest ripeness, causing low falling numbers in LMA genotypes (Mares and Mrva, 2008a).

Global Gene Expression Analysis of LMA

The transcriptome comparison between developing aleurone from +LMA and –LMA genotypes shows a limited number of abnormally expressed genes. One explanation for that is the apparent simplicity of the aleurone tissue, formed by just a single layer of identical cell types, which may have a reduced number of genes being expressed. Another possible explanation is that only about 2% of the aleurone cells in the +LMA genotypes undergo LMA (Mrva et al., 2006), so gene expression changes associated with LMA may be diluted. Of the 56 probes up-regulated in LMA-prone aleurone (Table I), three have been previously related to PCD (Initiation factor2 family protein, Programmed cell death protein2, and NucleaseI; Young and Gallie, 2000), consistent with the involvement of GA in LMA, as GA response leads to PCD in mature aleurone (Fath et al., 2000). Similarly, another two genes up-regulated during LMA have been reported to be induced by GA in rice and barley (Pathogenesis-related protein precursor and Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase; Yang et al., 2004; Chen and An, 2006). However, we have found several genes related to stress (Wali3, Wali5, and Wali6; Snowden et al., 1995) and ABA (ABA-inducible protein WRAB1; Tsuda et al., 2000) that are also up-regulated in the LMA samples and that suggest higher levels of ABA. The Wali genes affected by LMA belong to a particular group showing similarity to the Bowman-Birk protease inhibitors (Snowden et al., 1995), which are very abundant in seeds and have several putative functions, including the regulation of exogenous and endogenous seed proteases (Black et al., 2006). This class of Wali genes was not induced by GA in mature aleurone but was actually repressed, thus indicating clear discrepancies between the LMA phenomenon and the GA effects in mature aleurone.

Twenty-seven probes were up-regulated in the aleurone of –LMA genotypes (Table II). Of these, the most striking fold-change expression difference was recorded for the probe A_99_P142933, possibly suggesting a principal role for the gene in repressing LMA during grain development. However, the lack of similarity between that sequence and any known gene makes it difficult to speculate about its function. Interestingly, this gene was not induced by GA in mature aleurone. A gene encoding a γ-thionin was up-regulated at both 20 and 23 DPA, and these proteins have been shown to inhibit insect α-amylase (Pelegrini and Franco, 2005). Another probe up-regulated at both 20 and 23 DPA shows great similarity with the rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic gene Diminuto (Hong et al., 2005) and could suggest a deficiency in brassinosteroids in the LMA-prone aleurone. Interestingly, a barley homolog of this gene was found to be down-regulated by GA in mature barley aleurone (Chen and An, 2006), but we could not detect its expression in mature wheat aleurone. A probe with similarity to manganese superoxide dismutase is also up-regulated in the non-LMA aleurone, and this protein is an antioxidant that has been shown to retard aleurone PCA (Fath et al., 2000).

In summary, microarray results show a very limited number of genes affected by LMA. The expression of some of them could be explained by an increase in GA signaling in the developing aleurone; however, several others seem to be more related to stress signals and possibly driven by ABA. This is in marked contrast with mature aleurone, where GA and ABA act in opposition and are not found together (Fath et al., 2000).

Hormonal Changes Associated with LMA

Several lines of evidence, such as the reduction of LMA in GA-insensitive phenotypes and the microarray analysis, suggest that hormones are involved in the development of LMA. We have proved that by detailed hormone measurements. We found that ABA concentration was 2-fold higher in the samples with LMA, consistent with the microarray expression data, in which stress- and ABA-related genes were up-regulated in +LMA aleurone. Several other ABA-related metabolites were assayed, but their concentrations were similar in all samples. In relation to GAs, 14 metabolites were assayed, but only GA19, GA44, GA29, GA8, and GA24 were detected and quantifiable (Supplemental Table S3). All but one (GA24) of the quantified GAs belong to the early 13-hydroxylation biosynthetic pathway (Sponsel and Hedden, 2004), which suggests that this is the major biosynthetic route in wheat grains. Some other GA compounds have been found in wheat grains (Gale and Lenton, 1987), but due to the lack of standards, they were not analyzed. Neither the active form GA1 nor GA4, the active form in the nonhydroxylation pathway, was detected, but 20- and 6-fold increases in the precursors GA19 and GA44, respectively were found. Importantly, the presence of GA8, which is an inactive form derived from GA1, was detected in +LMA samples but not in –LMA genotypes. These changes provide strong evidence for active GA and GA flux in the +LMA samples but not in the LMA-free genotypes. In addition, large differences in the levels of auxins (IAA) between +LMA and –LMA were observed. Auxins levels were 4 times higher in –LMA samples, in apparent contradiction of previous studies that reported a positive effect of auxin on the production of GA (Singh and Paleg, 1986).

Whether the changes in concentration of these hormones are cause or effect of the expression of LMA remains unclear. However, the large differences in hormone content are more likely to have originated from differences existing in the whole tissue and not just from the small number of aleurone cells that produce LMA. This scenario envisages a deeply altered hormonal environment across the entire aleurone of +LMA genotypes during and prior to the expression of LMA. Under these conditions, some of the aleurone cells could escape their normal regulation and trigger a partial GA response, producing very transiently α-Amy expression. This model would fit very well with the increased concentration of GAs and ABA observed in +LMA genotypes: ABA could suppress almost totally the GA effect, but in some cells, small changes in hormones and/or sensitivity could generate abnormal gene expression. Whether changes in GAs and ABA concentrations occur simultaneously or if one precedes the other is still to be investigated. At the gene expression level, changes in genes related to the hormones GA and ABA have been identified. On the basis of the microarray analysis, genes related to GA would appear to be altered earlier (20 DPA) than the genes related to ABA (at 23 DPA), suggesting that changes in GAs would appear before changes in ABA. In addition to the changes in endogenous hormones reported in this study, earlier studies have also highlighted the possibility that LMA expression may also be associated with increased GA sensitivity in LMA-prone lines compared with non-LMA lines (Mares and Mrva, 2008a; Kondhare et al., 2012). A detailed hormonal profiling and analysis of GA signaling components during grain development is required to resolve these critical questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Sets of tall genotypes of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) with and without LMA were selected from a doubled haploid population, cv Spica rht (LMA)/cv Maringa Rht1 (non-LMA), based on a consistent phenotype over several seasons and alleles at the LMA 7B QTL (Mrva and Mares, 2001b). Doubled haploid lines 41, 47, 84, and 109, which have a non-LMA phenotype, were compared with lines 25, 52, 127, and 131, which express constitutive LMA. Tall genotypes were selected to avoid the confounding effects of the semidwarfing, GA-insensitive gene Rht1 on LMA expression (Mares and Mrva, 2008a). Plants were grown side by side in pots in a glasshouse, and spikes were tagged at anthesis. Spikes (10 per sampling time) were sampled at 12, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35, 40, and 45 DPA for determination of grain moisture, grain dry weight, grain appearance, high-pI α-amylase abundance, and isolation of aleurone tissue for preparation of mRNA. Between anthesis and grain maturity, the mean minimum and maximum temperatures were 16°C (range, 12.8°C–20.5°C) and 25.3°C (range, 21.4°C–31.4°C), respectively. Thermal time calculations were based on a summation of physiologically effective temperatures postanthesis (thermal time after anthesis = [average daily temperature – basal temperature for postanthesis development] × number of days after anthesis, where basal temperature for postanthesis development is 9.5°C; Angus et al., 1981; Slafer and Savin, 1991).

Grain Moisture and Grain Dry Weight

Duplicate samples of 20 grains were removed from the central part of the spikes, using only grains from the first and second florets. They were immediately weighed, dried at 100°C for 2 d, and weighed again. Grain moisture content was calculated as percentage fresh weight from the difference.

Determination of High-pI α-Amylase Content

For the extraction of α-amylase, eight replicates each of five deembryonated grains per sampling time were crushed, mixed with 1 mL of 0.85 m NaCl containing 0.018 m CaCl2 on a vortex mixer, incubated at 37°C overnight, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm in a microfuge. An aliquot of 100 μL was used in the ELISA determination of high-pI α-amylase protein. High-pI α-amylase protein was assayed in a 96-well plate format using a modification of the sandwich ELISA reported by Verity et al. (1999). Plates were coated with a rabbit anti-wheat α-amylase polyclonal antibody, blocked with bovine serum albumin, incubated with extracts of grain, washed, and then incubated with a mouse anti-barley high-pI α-amylase monoclonal antibody. The plates were again washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled donkey anti-mouse antibody (Sigma) before adding color developer, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Elisa Systems), and then recording optical density at 595 nm in a microplate reader. Color change was measured with a microplate spectrophotometer, and α-amylase protein in extracts was expressed as the mean of the optical density of eight microplate wells minus the optical density for a non-LMA control, a bulk sample of Sunco grain previously shown to be ELISA negative, samples of which were included on all ELISA plates. The polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies are currently maintained by the South Australian Research and Development Institute and made available under a research-only agreement between the Grains Research and Development Corporation of Australia and Bayer AG, the holder of the patent covering the use of these antibodies for the determination of α-amylase in wheat. α-Amylase activity in grain extracts was determined using the Amylazyme dye-labeled substrate assay (Megazyme International).

Isolation of Aleurone Tissue

Based on preliminary experiments, it was anticipated that high-pI α-amylase would be synthesized in +LMA genotypes beginning at 20 to 23 DPA. Consequently, grain from samples collected at 17, 20, 23, and 26 DPA was used for the isolation of grain coat plus aleurone, according to the method described by Mrva et al. (2006). Fifty grains per sample were deembryonated, the crease tissue was removed, and the aleurone was cleaned of starchy endosperm with a scalpel. The tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until required for RNA isolation.

Mature aleurone layers were isolated from grains of cv Spica as described previously (Chrispeels and Varner, 1967), except that the embryoless half-grains were imbibed only for 24 h. The isolated layers were incubated in flasks containing 2 mL of 10 mm CaCl2, 150 μg mL−1 cefotaxime, 50 units mL−1 nystatin, and either no hormone (control) or 1 µm GA3 at 25°C for 24 h. The layers were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until required for RNA isolation.

Gene Expression Analysis

Samples used in the microarray experiment were dissected from +LMA and –LMA developing aleurone layers. RNA was prepared using the hexadecyltrimethylammonium method described by Chang et al. (1993). Twenty aleurone layers were ground in liquid nitrogen, and the powder was added to 5 mL of hot extraction buffer. Following purification, 25 µg was further purified on a Qiagen RNeasy column (Qiagen). The RNA quality was checked on formaldehyde gel (1.2% agarose). Probe synthesis, labeling, and hybridization to the Wheat Gene Expression 44K chip, which contains 43,663 unique probes targeted to 40,606 unique ESTs (Agilent Technologies), were carried out at the Australian Genome Research Facilities. Microarray analyses were performed on three independent +LMA doubled haploid lines and three independent –LMA doubled haploid lines, which were treated as biological replicates.

Expression data were analyzed in R. Raw data were corrected for background (BGMedianSignal) and normalized between samples using quantile normalization. Fold change values and statistically significant differential expression were calculated using the Limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data; Smyth, 2005) package from Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org). Differentially expressed genes with P < 0.01 and fold change thresholds of absolute 1.5 were used in final comparisons. The normalized expression of all the probes in all the samples was extracted and is shown in Supplemental Table S1.

For real-time PCR, RNA from developing or mature aleurone was isolated using the same protocol as described in the microarray section. A total of 2 µg of total RNA was then used to synthesize cDNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen Life Sciences) following the supplier’s recommendations in 20-µL reactions. RNA extractions were performed on three biological replicates of 15 embryos isolated from hydrated or dry grains. cDNA was diluted 50-fold, and 10 µL was used in 20-µL PCRs with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen Life Sciences) and SYBR Green (Invitrogen). Reactions were run on a Rotor-gene 3000A real-time PCR machine (Corbett Research), and data were analyzed with Rotor-gene software using the comparative quantification tool. The expression of TaActin1 (Ji et al., 2011) was used as an internal control to normalize gene expression. Three biological replicates were performed for each experiment. Primer sequences are given in Supplemental Table S1.

Hormone Analysis

Twenty deembryonated 23-DPA grains from +LMA (lines 25, 52, and 131) and –LMA (lines 41, 47, and 84) genotypes were frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. Hormone profiling was carried out at the Plant Biotechnology Institute of the National Research Council of Canada (http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/eng/facilities/pbi/plant-hormone.html) following the methods described by Chiwocha et al. (2003) and Zaharia et al. (2005) by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Two technical replicates were analyzed.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Microsections of aleurone cell layers from −LMA and +LMA developing grains.

Supplemental Figure S2. Validation of selected microarray probes by qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used for qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Table S2. Normalized microarray expression in all samples.

Supplemental Table S3. Hormonal analysis of 23 DPA +LMA and −LMA developing grains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Trijntje Hughes, Kerrie Ramm, and Hai-Yunn Law for their expert and invaluable technical assistance. We also thank Drs. Peter Chandler and Jean-Philippe Ral for critical reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

- LMA

late maturity α-amylase

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- ABA

abscisic acid

- +LMA

line expressing constitutive LMA

- –LMA

line not expressing LMA

- QRT

quantitative reverse transcription

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- PCD

programmed cell death

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- FGAS

Functional Genomics of Abiotic Stress Project

References

- Angus JF, Mackenzie DH, Morton R, Schafer CA. (1981) Phasic development in field crops. II. Thermal and photoperiodic responses of spring wheat. Field Crops Res 4: 269–283 [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C, Black M, Chapman JM, Norman HA, Angold R. (1982) The induction of sensitivity to gibberellin in aleurone tissue of developing wheat grains. I. The effect of dehydration. Planta 154: 573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulcombe DC, Buffard D. (1983) Gibberellic-acid-regulated expression of alpha-amylase and 6 other genes in wheat aleurone layers. Planta 157: 493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Bewley JD, Halmer P (2006) The Encyclopedia of Seeds: Science, Technology and Uses. CAB International, Wallingford, UK [Google Scholar]

- Chang SJ, Puryear J, Cairney J. (1993) A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol Biol Rep 11: 113–116 [Google Scholar]

- Chen KG, An YQC. (2006) Transcriptional responses to gibberellin and abscisic acid in barley aleurone. J Integr Plant Biol 48: 591–612 [Google Scholar]

- Chiwocha SDS, Abrams SR, Ambrose SJ, Cutler AJ, Loewen M, Ross ARS, Kermode AR. (2003) A method for profiling classes of plant hormones and their metabolites using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: an analysis of hormone regulation of thermodormancy of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) seeds. Plant J 35: 405–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Varner JE. (1967) Gibberellic acid-enhanced synthesis and release of α-amylase and ribonuclease by isolated barley and aleurone layers. Plant Physiol 42: 398–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emebiri LC, Oliver JR, Mrva K, Mares D. (2010) Association mapping of late maturity alpha-amylase (LMA) activity in a collection of synthetic hexaploid wheat. Mol Breed 26: 39–49 [Google Scholar]

- Eradatmand DA, Houshmasdfar A, Eghdami A. (2011) Endogenous gibberellins and abscisic acid levels during grain development of durum wheat genotypes. Adv Environ Biol 5: 1080–1084 [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kettlewell PS. (2008) The effect of temperature shock and grain morphology on alpha-amylase in developing wheat grain. Ann Bot (Lond) 102: 287–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fath A, Bethke P, Lonsdale J, Meza-Romero R, Jones R. (2000) Programmed cell death in cereal aleurone. Plant Mol Biol 44: 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale MD, Lenton JE. (1987) Preharvest sprouting in wheat a complex genetic and physiological problem affecting bread-making quality of UK wheats. Asp Appl Biol 15: 115–124 [Google Scholar]

- Gubler F, Kalla R, Roberts JK, Jacobsen JV. (1995) Gibberellin-regulated expression of a myb gene in barley aleurone cells: evidence for Myb transactivation of a high-pI α-amylase gene promoter. Plant Cell 7: 1879–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler F, Raventos D, Keys M, Watts R, Mundy J, Jacobsen JV. (1999) Target genes and regulatory domains of the GAMYB transcriptional activator in cereal aleurone. Plant J 17: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Hasegawa Y, Ashikari M, Kitano H, Matsuoka M. (2005) The rice brassinosteroid-deficient dwarf2 mutant, defective in the rice homolog of Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1, is rescued by the endogenously accumulated alternative bioactive brassinosteroid, dolichosterone. Plant Cell 17: 2243–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Dong B, Shiran B, Talbot MJ, Edlington JE, Hughes T, White RG, Gubler F, Dolferus R. (2011) Control of abscisic acid catabolism and abscisic acid homeostasis is important for reproductive stage stress tolerance in cereals. Plant Physiol 156: 647–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LW, Kermode AR, Jones RL. (1996) Premature drying increases the GA-responsiveness of developing aleurone layers of barley (Hordeum vulgare L) grain. Plant Cell Physiol 37: 1116–1125 [Google Scholar]

- King RW. (1976) Abscisic-acid in developing wheat grains and its relationship to grain-growth and maturation. Planta 132: 43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosaki T, Asakura T, Matsumoto I, Tamura T, Terauchi K, Funaki J, Kuroda M, Misaka T, Abe K. (2009) Wheat cysteine proteases triticain alpha, beta and gamma exhibit mutually distinct responses to gibberellin in germinating seeds. J Plant Physiol 166: 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondhare KR, Kettlewell PS, Farrell AD, Hedden P, Monaghan JM. (2012) Effects of exogenous abscisic acid and gibberellic acid on pre-maturity α-amylase formation in wheat grains. Euphytica 188: 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus CM, Baulcombe DC, Martienssen RA. (1985) Alpha-amylase genes of wheat are 2 multigene families which are differentially expressed. Plant Mol Biol 5: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares D, Mrva K. (2008a) Late-maturity alpha-amylase: low falling number in wheat in the absence of preharvest sprouting. J Cereal Sci 47: 6–17 [Google Scholar]

- Mares D, Mrva K. (2008b) Genetic variation for quality traits in synthetic wheat germplasm. Aust J Agric Res 59: 406–412 [Google Scholar]

- Mares DJ, Gale MD (1990) Dormancy and preharvest sprouting tolerance in white-grained and red-grained wheats. In K Ringlund, E Mosleth, DJ Mares, eds, Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Preharvest Sprouting in Cereals. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, pp 75–84 [Google Scholar]

- Mounla MAK, Bangerth F, Story V. (1980) Gibberellin-like substances and indole type auxins in developing grains of normal-lysine and high-lysine genotypes of barley. Physiol Plant 48: 568–573 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Mares DJ. (1996a) Inheritance of late maturity alpha-amylase in wheat. Euphytica 88: 61–67 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Mares DJ. (1996b) Expression of late maturity alpha-amylase in wheat containing gibberellic acid insensitivity genes. Euphytica 88: 69–76 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Mares D, Cheong J (2008) Genetic mechanisms involved in late maturity α-amylase in wheat. In R Appels, R Eastwood, E Lagudah, P Langridge, M MacKay, L McIntyre, P Sharp, eds, Proceedings of the 11th International Wheat Genetics Symposium. Sydney University Press, Brisbane, Australia, pp 940–942 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Mares DJ. (2001a) Induction of late maturity alpha-amylase in wheat by cool temperature. Aust J Agric Res 52: 477–484 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Mares DJ. (2001b) Quantitative trait locus analysis of late maturity alpha-amylase in wheat using the doubled haploid population Cranbrook × Halberd. Aust J Agric Res 52: 1267–1273 [Google Scholar]

- Mrva K, Wallwork M, Mares DJ. (2006) α-Amylase and programmed cell death in aleurone of ripening wheat grains. J Exp Bot 57: 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy J, Fincher GB. (1986) Effects of gibberellic-acid and abscisic-acid on levels of translatable messenger-RNA (1-3,1-4)-beta-d-glucanase in barley aleurone. FEBS Lett 198: 349–352 [Google Scholar]

- Murray F, Matthews P, Jacobsen J, Gubler F. (2006) Increased expression of HvGAMYB in transgenic barley increases hydrolytic enzyme production by aleurone cells in response to gibberellin. J Cereal Sci 44: 317–322 [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrini PB, Franco OL. (2005) Plant gamma-thionins: novel insights on the mechanism of action of a multi-functional class of defense proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2239–2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley M. (1979) Role of gibberellin, abscisic acid, and auxin in the regulation of developing wheat grains. J Exp Bot 30: 381–389 [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Paleg LG. (1986) Comparison of IAA-induced and low temperature-induced GA3 responsiveness and α-amylase production by GA3-insensitive dwarf wheat aleurone. Plant Physiol 82: 685–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slafer GA, Savin R. (1991) Developmental base temperature in different phonological phases of wheat (Triticum aestivum). J Exp Bot 42: 1077–1082 [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK (2005) Limma: linear models for microarray data. In R Gentleman, V Carey, S Dudoit, WH Irizarry, eds, Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solution Using R and Bioconductor. Springer, New York, pp 397–420 [Google Scholar]

- Snowden KC, Richards KD, Gardner RC. (1995) Aluminum-induced genes: induction by toxic metals, low calcium, and wounding and pattern of expression in root tips. Plant Physiol 107: 341–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel VM, Hedden P (2004) Gibberellin biosynthesis and inactivation. In PJ Davies, ed, Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 63–94 [Google Scholar]

- Tan MK, Verbyla AP, Cullis BR, Martin P, Milgate AW, Oliver JR. (2010) Genetics of late maturity alpha-amylase in a doubled haploid wheat population. Crop Pasture Sci 61: 153–161 [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K, Tsvetanov S, Takumi S, Mori N, Atanassov A, Nakamura C. (2000) New members of a cold-responsive group-3 Lea/Rab-related Cor gene family from common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genes Genet Syst 75: 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity JCK, Hac L, Skerritt JH. (1999) Development of a field enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of alpha-amylase in preharvest-sprouted wheat. Cereal Chem 76: 673–681 [Google Scholar]

- Yang GX, Jan A, Shen SH, Yazaki J, Ishikawa M, Shimatani Z, Kishimoto N, Kikuchi S, Matsumoto H, Komatsu S. (2004) Microarray analysis of brassinosteroids- and gibberellin-regulated gene expression in rice seedlings. Mol Genet Genomics 271: 468–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JC, Zhang JH, Wang ZQ, Zhu QS. (2003) Hormones in the grains in relation to sink strength and postanthesis development of spikelets in rice. Plant Growth Regul 41: 185–195 [Google Scholar]

- Young TE, Gallie DR. (2000) Programmed cell death during endosperm development. Plant Mol Biol 44: 283–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharia LI, Galka MM, Ambrose SJ, Abrams SR. (2005) Preparation of deuterated abscisic acid metabolites for use in mass spectrometry and feeding studies. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 48: 435–445 [Google Scholar]