Abstract

Purpose

The objectives of this study were to describe our surgical management with a modified total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) and to evaluate the clinical effects in patients with thoracolumbar tumors.

Methods

Sixteen consecutive patients with thoracolumbar neoplasms underwent a modified TES via single posterior approach followed by dorsoventral reconstruction from December 2008 to July 2011. Details of the modified technique were described and the patients’ clinical information was retrospectively reviewed and analyzed.

Results

Significant improvements in neurological function were achieved in most of the patients. Local pain or radicular leg pain was relieved postoperatively. The mean operation time was 7.2 h, with an average blood loss of 2,300 ml. No major complications, instrumentation failure or local recurrence was found at the final follow-up. Five patients died of the disease during mean 14-month (3.0–23) follow-up.

Conclusions

The modified TES with a single posterior approach is feasible, safe and effective for thoracolumbar spine tumors.

Keywords: Total en bloc spondylectomy, Modified surgical techniques, Spinal tumors, Single posterior approach, Thoracolumbar spine

Introduction

Total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) is a relatively new surgical technique that uses a T-saw for spinal tumors [1–3]. The TES technique is different from traditional intralesional resection with the characteristic of removing the whole vertebra, body and lamina as one compartment to achieve wide tumor excision. TES can be performed through staged or combined anterior and posterior approaches, or from a posterior-only approach. The posterior-only approach proffers the merit of achieving complete tumor excision and circumferential spinal reconstruction in a single setting. Some studies have demonstrated TES’s clinical utility and safety [3–8]. Briefly, The posterior-only approach in TES is composed of two steps: en bloc resection of the posterior element (en bloc laminectomy) and en bloc resection of the anterior part (en bloc corpectomy) [3]. Theoretically, however, the procedure of TES for thoracic spinal tumors may result in severe complications such as mechanical damages to the spinal cord or major vessels, which make it technically challenging, as such its application is restricted. Particularly for the procedure of en bloc corpectomy, the dissection for vertebral column by T-saw reciprocating from anterior to posterior is dangerous to the cord using the original methods. Several surgical teams, including the author’s, have developed or modified tools for TES. T-saw has been replaced with arc osteotomes completely [9]. Modified dissection for corpectomy is characterized using a disk puncture needle with sleeve for guiding a T-saw in posterior–anterior direction in tile plane between dura mater and disk [10].

The purposes of this study were to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of our modified technique for TES via a single posterior approach, and to retrospectively evaluate the clinical effects in thoracic and lumbar tumors.

Patients and methods

Patients’ backgrounds and tumor characteristics

This study had been approved by the ethics committee of our hospital. All the surgical procedures were done with informed consent from the patients. Sixteen patients with thoracic or lumbar tumors were treated with a modified TES via one-stage single posterior approach at the authors’ institution from December 2008 to July 2011. Clinical information was collected from the records including age, sex, medical history, symptoms, neurologic findings, radiographs, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), pathological diagnosis and follow-up interviews. The diagnosis of spinal tumors was based on the observation of typical findings in diagnostic imaging studies. The Tokuhashi scoring system [11] was employed in preoperative assessment for prognosis of metastatic spinal tumor and Tomita’s scoring system [3] was used to determine the best therapeutic option for the patient prior to surgery.

The patients’ backgrounds, tumor characteristics and surgical classification for these patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Two patients had a primary tumor of the spine (Giant cell tumor, neurinoma) and 14 patients had metastatic spinal diseases (Table 2). Nine patients out of 11 cases who had thoracic spinal tumors suffered cord deficit. Five patients had isolated root deficit resulting from lumbar tumor. In spinal metastatic patients, 4 of 14 patients scored 9 and 10 patients scored between 10 and 13.

Table 1.

Patients’ backgrounds

| Number of patients | 16 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 (68.8 %) |

| Female | 5 (31.2 %) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 54.4 ± 12.4 |

| Range | 32–76 |

| Previous treatment | |

| Surgical for primary tumors outside spine | 7 (43.8 %) |

| Chemotherapy | 8 (50 %) |

| Radiation treatment | 7 (43.8 %) |

| Concurrent analgesics | 16 (100 %) |

| Intra-operative wake-up test only | 1 (6.25 %) |

| Intra-operative evoked potentials | 6 (37.5 %) |

Table 2.

Tumor characteristics, operation duration and blood loss

| Number of spinal tumors | 16 |

| Pathology diagnosis | |

| Spine neurinoma | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Giant cell tumor of bone | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Lung cancer | 6 (37.5 %) |

| Colorectal cancer | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Suprarenal epithelioma | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Breast cancer | 1(6.3 %) |

| Adenocarcinoma metastatic | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Thyroid carcinoma | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Prostatic carcinoma | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Tumor location | |

| Th5 | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Th6 | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Th8 | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Th9 | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Th10 | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Th11 | 2 (12.5) |

| L1 | 2 (12.5 %) |

| L2 | 3 (18.7 %) |

| Tomita’s scoring system | |

| Type II | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Type III | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Type IV | 8 (50 %) |

| Type V | 6 (37.5 %) |

| Operation time (h) | |

| Mean | 7.2 ± 1.4 |

| Range | 5–10.3 |

| Blood loss (ml) | |

| Mean | 2300 ± 720 |

| Range | 1200–3500 |

Surgical procedure and modified techniques

Under general anesthesia, patients were placed in a prone position. After a dorsomedian skin incision, the paraspinal muscles were detached from the spinous processes and the laminae as well as the facet joints. In the thoracic spine, the dorsal parts of ribs adjacent to the costotransverse joint were resected leading to reach access to the ventral aspect of the vertebra with tumor. En bloc laminectomy was performed and bone surfaces of cut section were immediately sealed with bone wax. Intervertebral dissection of the neighboring disk spaces, the posterior and partially anterior longitudinal ligaments were performed carefully using a spatula and the surgeon’s fingers. Gentle and blunt dissection was performed on both sides through the interface between the pleura aorta as well as the iliopsoas muscle and the vertebral body in the thoracic and lumbar spine, respectively, which was then preceded by dissection and ligation of bilateral segmental arteries. In the thoracic spine, the nerve roots were ligated and cut.

Before en bloc corpectomy was performed, unilateral posterior instrumentation was installed to stabilize the spine. After gentle dissections of the spinal cord from the surrounding epidural venous plexus and/or the extended tumor margin in the spinal canal with a thin nerve dissector was completed, the original en bloc corpectomy characterized with “one-step dissection” from anterior to posterior [3] was modified by us to “two-step dissection” (Fig. 1): after the disk was cut by T-saw to the level about one-third middle–posterior, L-shape chisel was inserted into the dissected space and beat away posterior–anteriorly to join forces with the T-saw. Afterward, the affected vertebra was pushed forward about 5–10 mm and meticulously rotated along its longitudinal axis, achieving a circumferential decompression of the spinal cord and a segmental total en bloc corpectomy.

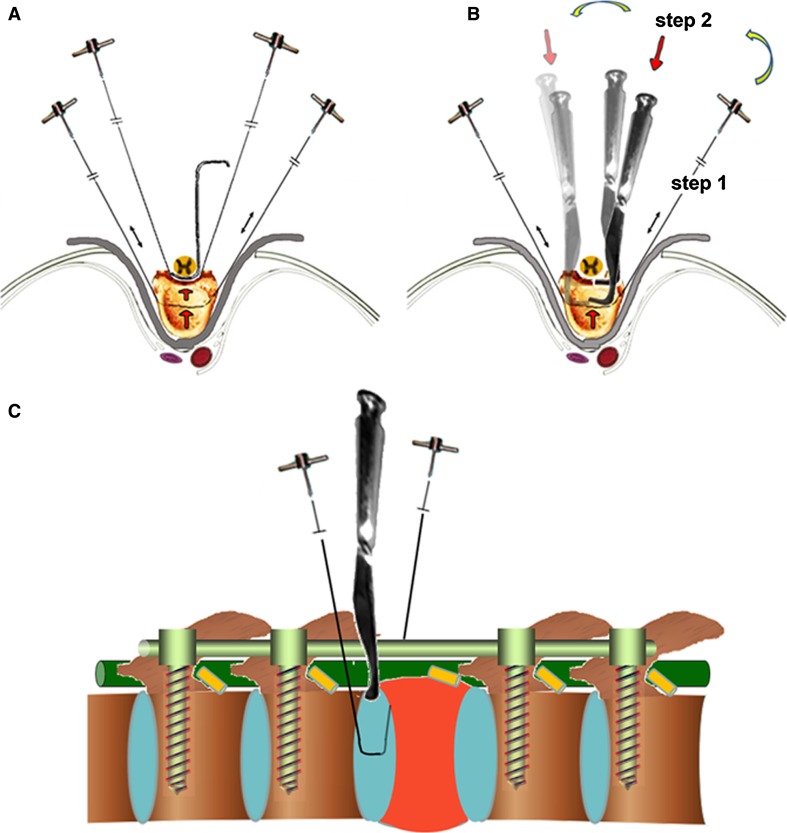

Fig. 1.

Scheme of the original method for en bloc resection of the anterior part (en bloc corpectomy) by using thread wire T-saw only (a) and the modified technique for en bloc corpectomy with L shape osteotome used subsequently with thread wire T-saw (b, c). Two step dissection for corpectomy: after the disk was cut by T-saw to the level about one-third middle-posterior, L-shape chisel was inserted into the dissected space and beat away posterior–anteriorly to join forces with the T-saw. Then, the affected vertebra was pushed forward about 5–10 mm and meticulous rotated along its longitudinal axis, achieving a circumferential decompression of the spinal cord and a segmental total en bloc corpectomy

Finally, dorsoventral reconstruction of the spine was carried out using cages filled with cancellous bone graft or bone substitutes [3] to achieve anterior stabilization and by the posterior instrumentation, at least two levels above and below the spondylectomy, respectively.

Postoperative management was characterized by wound drainage for 24–48 h and intrathoracic drain for those with pleura disruption or hemothorax within 5 days. Patients were mobilized after 1 week and instructed to wear a thoracolumbar brace for 3 months.

Complications were recorded including disruption of dural mater, the leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, iatrogenic spinal cord injury, major vessel damage, pleura disruption and wound infection.

Outcomes evaluation and follow-up

Radiating pain and local pain relief were assessed by a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS), where a score of 0 indicated ‘no pain’ and a score of 10 indicated ‘severe pain’. Neurologic function was assessed using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale [12] and muscle strength of lower limb was measured by manual muscle test only for those with lumbar tumors. Outcomes were assessed prior to surgery, 1 week and every 4 weeks post-operatively. All the patients were followed routinely by biplanar X-ray with or without CT-scan for the thoracic or lumbar spine.

Results

Feasibility and safety

All the patients were operated successfully (Figs. 2, 3). The average duration of the operations was 7.2 h, and the average blood loss was 2300 ml (Table 2). No iatrogenic spinal cord injury, major vessel damage, disruption of dura, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid and wound infection occurred while two pleura disruption happened during the operations which were remedied with intrathoracic drain successfully.

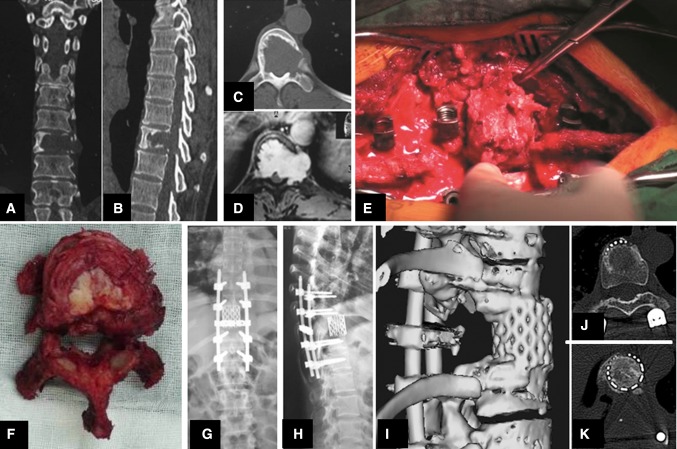

Fig. 2.

Illustrative case #1. Coronal and sagittal CT show Th10 vertebra is affected by a osteolytic lesion in a female 45-year-old patient (a, b). Axial CT scan and enhance contrast MR image reveal the pedicle involved under epidural and with paraspinal extension of the mass (c, d). Intraoperative view showing rotation of the Th10 vertebra around the longitudinal axis (e). Specimen of Th10-vertebral neurinoma after total en bloc excision (top view) (f). Postoperative biplanar radiographs demonstrate dorsoventral spinal instrumentation (g, h). At 12 months follow-up, postoperative 3-D reconstruction and transverse sections of the interfaces between host bone bed and vertebral body replacement (titanium mesh cage with autogenous bone inside) show that biologic spinal fusion has been achieved (i–k)

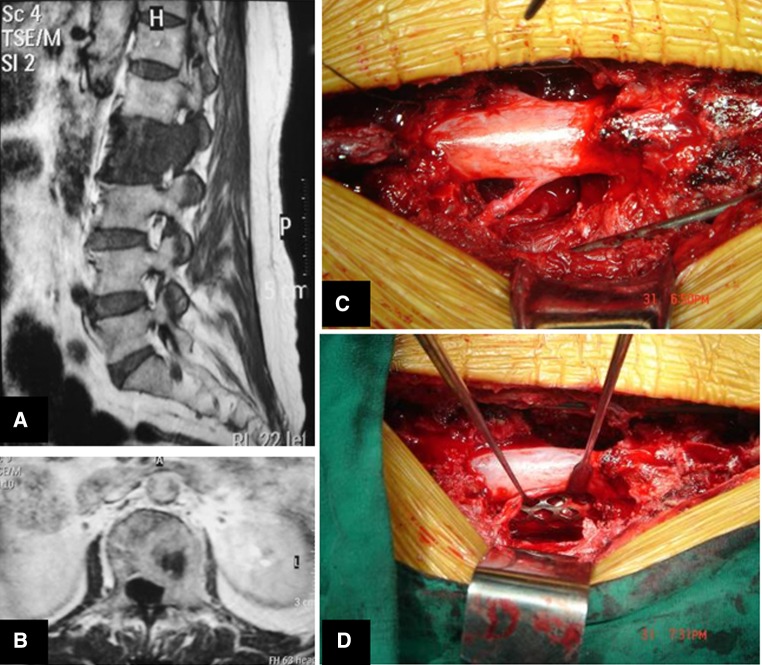

Fig. 3.

Illustrative case #2. Sagittal and coronal MRI demonstrating the L2 vertebra with metastatic lung cancer in a female 60-year-old patient (a, b). Intraoperative view showing spinal dura and nerve roots after en bloc corpectomy (c) and ventral reconstruction with anterior cage interposition (d)

Neurologic function and pain relief

Significant improvement in neurologic function was achieved in 13 patients, including eight patients with cord deficit and five patients with lumbar spinal lesions. Of these 13 patients, it was observed that neurologic deficits completely recovered in four patients with cord deficit, two patients with ASIA grade C and two was grade D before operation. Five lumbar tumor cases with radicular pain were relieved significantly and their muscle strengths of the involved muscle group upgraded to grade IV or above postoperatively (Table 3). There were six cases without any changes. Two was ASIA grade E preoperatively without any deterioration, one was ASIA grade A with metastatic lung cancer in T10 preoperatively, one was ASIA grade C and the other two remained at ASIA D. Local pain in all patients was also reduced dramatically after operation and continuous gradually relieved during follow up (Fig. 4). It remained at mild level with 0–3 score after 3 months and significantly improved over 6 months.

Table 3.

Functional outcome

| Pre-operation | Post-operation | |

|---|---|---|

| ASIA impairment scale for thoracic spinal tumors | ||

| ASIA A | 1 (1/11) | 1 (1/11) |

| ASIA C | 4 (2/11) | 1 (1/11) |

| ASIA D | 4 (4/11) | 3 (3/11) |

| ASIA E | 2 (2/11) | 6 (6/11) |

| VAS for radicular pain with lumbar spinal tumors | ||

| VAS 9 | 2 (2/5) | 0 |

| VAS 8 | 2 (2/5) | 0 |

| VAS 7 | 1 (1/5) | 0 |

| VAS 2 | 0 | 2 (3/5) |

| VAS 0 | 0 | 3 (3/5) |

| Muscle strength with lumbar spinal tumors | ||

| II | 2 (2/5) | 0 |

| III | 3 (3/5) | 0 |

| IV | 0 | 2 (2/5) |

| V | 0 | 3 (3/5) |

Fig. 4.

VAS at pre-operative and post-operative follow up. OP operative, n number of patients, w week, m month

Follow-up

Follow-up varied from 3 to 23 months (mean 14 months). Five patients died within the follow-up period, including one patient with hepatocellular carcinoma died at a little more than 3 months, three with lung cancer died at 5 months and one with rectal carcinoma died at 13 months, after surgery. No clinical evidence of local recurrence was found in all the patients at the time of the latest follow-up. No hardware failures or cage dislocations were observed with digital radiograph. Neurologic function of all patients did not deteriorate in follow-up.

Discussion

The results of our study had shown that TES performed with modification of the dissection for vertebral column by combining with T-saw and L shape osteotome was a feasible, safe technique for the treatment of the patients with spinal tumors.

Our results demonstrated that some patients remained neurologically stable and the others improved after the surgery. Street et al. [13] reported that out of 37 patients with ASIA cord deficit, who underwent a single-stage posterolateral vertebrectomy, nearly half of the patients improved one ASIA grade at the end of the follow-up. All the patients presented with an isolated root deficit and a single patient who was presented with Cauda Equina syndrome had made a complete recovery. Recently, a retrospective review on neurologic function after thoracic TES with regard to Frankel classification in 79 patients with thoracic-level spinal tumors that had been treated with TES, showed that there were no neurologic deterioration and neurologic improvement of at least 1 Frankel grade was achieved in 25 cases among 46 cases (54.3 %) with neurologic deficits before surgery [5]. Neurologic improvement was observed in 58 % of 76 consecutive patients with symptomatic spinal metastases treated with anterior spinal cord decompression with stabilization, and 93 % were able to walk postoperatively [14].

Similar improvements observed in pain relief occurred in our series as presented elsewhere [5]. A clinically relevant significant reduction in radicular pain and local pain were achieved within 1 week after TES, local pain then decreased gradually further at 3 months and was maintained on the same level for some time.

The duration of the operation was 7.2 ± 1.4 h (range 5–10.3), which was shorter than that of Melcher and colleagues reported at 9.2 ± 3.1 h (range 5.3–16.4) in 15 patients [8]. The difference lied in the fact that all our patients were only one vertebra involved but three patients in their series were multilevel involved. It was also a little shorter than the average time of the operation with 8.4 h (range 7.4–10.8 h) in single level TES treated with preoperative embolization of segmental arteries supplying the tumor only [3]. Meanwhile, intraoperative blood loss with 2300 ± 720 ml (range 1,200–3,500) in our series was similar to that of 2,612 ml (range 1,530–5,950 ml) in those embolization patients reported by Kawahara and co-workers [3]. All of their patients had thoracic hypervascular spinal tumors. However, our series were not all hypervascular tumors and our patients had not been performed preoperative embolization. In comparison to the original methods with embolization preoperatively and other modified techniques for TES aforementioned [9, 10], our method achieved convenient manipulation with a sound operation time and blood loss.

The morbidity of surgical procedures for spine tumors was higher than for other conditions, particularly for en bloc resections, the most technically demanding procedures. Forty-seven patients of 134 patients (34.3 %) reported by Boriani et al. [15] suffered a total of 70 complications (41 major and 29 minor complications). And 32 of 47 patients (32/47, 68.1 %) had 1 complication, while the rest had 2 or more. Three patients (3/134, 2.2 %) died from complications. In a series of 42 patients, who underwent the posterolateral vertebrectomy approach reported by street et al. [13], 20 patients suffered with one or more complications for an overall patient complication rate of 47 %. Eleven patients had a major complication (26 %). Nine (9/42, 21.4 %) patients required early reoperation and 7(7/42, 16.7 %) of them had wound failure. Wang et al. [16] reported there was an overall major complication rate of 25.3 % using the single-stage posterolateral transpedicular approach for 140 patients with the epidural metastatic spine tumors. Major operative complications occurred in 20 patients (14.3 %). Wound complications occurred in 16 patients (11.4 %).

Compared with these series, patients in our study didnot suffer any major iatrogenic complications of TES. There was pneumothorax in two patients because of pleura disruption. The procedure of rotation and remove of tumorical vertebral with extent at the lateral side led to pleura disruption in one patient. And the other one happened in the dissection around the vertebral. It was successfully managed by intrathoracic drain remedy within 5 days. We did not encounter any wound-related complications or infections in our series.

Our results also confirmed that en bloc resection via a single posterior approach and single segment involved seemed less risky. Multisegmental resections and operations including double contemporary approaches were identified as the top two factors significantly affecting the morbidity [15].

Local recurrence directly led to poor prognosis and needed reoperation if applicable. However, revision for spinal tumors no matter primary or metastatic was highly risky and always unsuccessful. En bloc resection had been reported about 7.1 % local recurrence in non-contaminated cases [15]. Our series had no evidence of local relapse.

Taken together, the absence of major TES-related complications and the lack of need for surgical revision in our study highlighted the safety and sound oncologic outcomes of this modified procedure.

The principle of en bloc resection for primary spinal tumors had been well accepted [17]. However, the indication of TES for spinal metastasis still remained controversial [18, 19]. Interestingly, there were more cases with metastasis underwent TES than that with primary tumors in literature [1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 17, 18, 20–23]. We believed that it was mainly because that primary spinal tumors were rare with less than 5 % of all primary musculoskeletal tumors. However, almost all the major types of systemic cancer could metastasize to the spinal column. In our series, there were 14 spinal metastases versus 2 primary lesions. Actually, TES had achieved encouraging clinical results in 24 patients with spinal metastasis [2]. Even in one of the extremely poor-prognosis cancers, lung cancer spinal metastasis, one recent study in small series showed that TES also was appropriate in managing for selected cases with controllable primary lung cancer, localized spinal metastasis, and no visceral metastasis [4]. In our study, a short survival was observed in four cases, one with hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis and the other three with lung cancer metastases. Other ten patients with relatively good-prognosis spinal metastases treated with our technique had achieved a more than 6 months survival with pain relief. TES might remain too invasive a surgery in such cases. However, when combined with multidisciplinary approach, TES was a promising option for spinal metastatic disease especially for those with good-prognosis localized metastasis or metastatic epidural compression of the spinal cord [24].

There were some limitations in our study. First, it was a retrospective analysis with small number of patients with short-term follow up. Secondly, it must be cautioned that the spinal cord might be damaged when the L-shaped osteotome was inserted into the epidural space with incomplete dissection between the ventral dura and vertebral or the tumor posterior margin. However, this was rare, meticulous and complete dissections played key role in this step. Intraoperative neuromonitoring, including wake-up test and evoked potentials is helpful when surgery was involved in the spinal cord region especially for those with tumor extended to the spinal canal over a large area in order to create a safer, optimal environment and to minimize neurologic deficit [25]. Evoked potentials is a real-time, sensitive and valuable monitoring tool for optimization of outcome in complex spinal surgery. Today, combined SSEP and MEP are advocated during spinal procedures. However, a lot of factors can influence successful intra-operative SSEP and MEP, such as anesthesia agents, neuromuscular blocking drugs, hypotension, hypothermia [26]. Therefore, the intra-operative wake-up test is still considered to be the ‘gold standard’ and consists of patient awakening with observation of voluntary limb movement. Wake-up test is not a continual and real-time monitoring method. Moreover, not all patients are good candidates for a wake-up test, such as retarded patients, infants and young children. They might need SSEP or MEP during operation. Paraplegic patients are also not good candidates for either wake-up test or SSEP/MEP, but certainly benefit from intra-operative SSEP and MEP to prevent deterioration of existing neurologic deficits [27].

In addition, the spinal metastases were dominated in our series while spinal primary tumors and metastases had different prognosis. Furthermore, our cases had not been performed with preoperative embolization, especially preoperative triple-level embolization, which had been proved in a significant reduction for intraoperative blood loss while no statistic influence on shortening in operation time [3]. Nevertheless, the results of current study had shown that it was worthy of further investigation in prospective large scale with long-term follow up for primary and metastatic spinal tumors, respectively.

Conclusions

In summary, TES with the modified en bloc corpectomy via a single posterior approach is a promising and useful therapeutic option for thoracic and lumbar primary or selected secondary tumors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 30901506, 30973033) and the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (Grant no. 10151008901000155, 8151008901000094).

Conflict of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Lin Huang, Phone: +86-20-8133-2523, FAX: +86-20-8133-2853, Email: hakkahuanglin@gmail.com.

Keng Chen, Email: hellochenkeng@gmail.com.

Ji-chao Ye, Email: yejichao8357@163.com.

Yong Tang, Email: tangyong8888@hotmail.com.

Rui Yang, Email: yangrui1977@126.com.

Peng Wang, Email: sunfox809@yahoo.com.cn.

Hui-yong Shen, Phone: +86-20-8133-2507, FAX: +86-20-8133-2853, Email: shenhuiyong@yahoo.com.cn.

References

- 1.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, Tsuchiya H, Nagata S, Toribatake Y. Total en bloc spondylectomy for solitary spinal metastases. Int Orthop. 1994;18:291–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00180229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomita K, Toribatake Y, Kawahara N, Ohnari H, Kose H. Total en bloc spondylectomy and circumspinal decompression for solitary spinal metastasis. Paraplegia. 1994;32:36–46. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawahara N, Tomita K, Murakami H, Demura S. Total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors: surgical techniques and related basic background. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murakami H, Kawahara N, Demura S, Kato S, Yoshioka K, Tomita K. Total en bloc spondylectomy for lung cancer metastasis to the spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:414–417. doi: 10.3171/2010.4.SPINE09365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakami H, Kawahara N, Demura S, Kato S, Yoshioka K, Tomita K. Neurological function after total en bloc spondylectomy for thoracic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12:253–256. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.SPINE09506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsieh PC, Li KW, Sciubba DM, Suk I, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL (2009) Posterior-only approach for total en bloc spondylectomy for malignant primary spinal neoplasms: anatomic considerations and operative nuances. Neurosurgery 65:173–181; discussion 181. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345630.47344.17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Nishida K, Doita M, Kawahara N, Tomita K, Kurosaka M. Total en bloc spondylectomy in the treatment of aggressive osteoblastoma of the thoracic spine. Orthopedics. 2008;31:403. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080401-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melcher I, Disch AC, Khodadadyan-Klostermann C, Tohtz S, Smolny M, Stockle U, Haas NP, Schaser KD. Primary malignant bone tumors and solitary metastases of the thoracolumbar spine: results by management with total en bloc spondylectomy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1193–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0295-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HuaZi Xu, YongLong Chi, XiaoLong S. Spondylectonmy en bloc for thoracic and lumbar tumors via posterior approach. Chin J Spine Spinal Cord. 2009;19:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo C, Yan Z, Zhang J, Jiang C, Dong J, Jiang X, Fei Q, Meng D, Chen Z (2010) Modified total en bloc spondylectomy in thoracic vertebra tumour. Eur Spine J. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1618-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, Oshima M, Ryu J. A revise scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine. 2005;30:2186–2191. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180401.06919.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maynard FM, Jr, Bracken MB, Creasey G, Ditunno JF, Jr, Donovan WH, Ducker TB, Garber SL, Marino RJ, Stover SL, Tator CH, Waters RL, Wilberger JE, Young W. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Am Spinal Injury Assoc Spinal Cord. 1997;35:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Street J, Fisher C, Sparkes J, Boyd M, Kwon B, Paquette S, Dvorak M. Single-stage posterolateral vertebrectomy for the management of metastatic disease of the thoracic and lumbar spine: a prospective study of an evolving surgical technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:509–520. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180335bf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weigel B, Maghsudi M, Neumann C, Kretschmer R, Muller FJ, Nerlich M. Surgical management of symptomatic spinal metastases. Postoperative outcome and quality of life. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:2240–2246. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boriani S, Bandiera S, Donthineni R, Amendola L, Cappuccio M, De Iure F, Gasbarrini A. Morbidity of en bloc resections in the spine. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1137-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JC, Boland P, Mitra N, Yamada Y, Lis E, Stubblefield M, Bilsky MH. Single-stage posterolateral transpedicular approach for resection of epidural metastatic spine tumors involving the vertebral body with circumferential reconstruction: results in 140 patients. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:287–298. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher CG, Keynan O, Boyd MC, Dvorak MF. The surgical management of primary tumorsof the spine: initial results of an ongoing prospective cohort study. Spine. 2005;30:1899–1908. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000174114.90657.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falicov A, Fisher CG, Sparkes J, Boyd MC, Wing PC, Dvorak MF. Impact of surgical intervention on quality of life in patients with spinal metastases. Spine. 2006;31:2849–2856. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245838.37817.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao KC, Boriani S, Gokaslan ZL, Sundaresan N. En bloc spondylectomy for spinal metastases: a review of techniques. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawahara N, Tomita K, Matsumoto T, Fujita T. Total en bloc spondylectomy for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Chir Organi Mov. 1998;83:73–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komagata M, Nishiyama M, Imakiire A, Kato H. Total spondylectomy for en bloc resection of lung cancer invading the chest wall and thoracic spine—Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:353–357. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda Y, Sakayama K, Sugawara Y, Miyawaki J, Kidani T, Miyazaki T, Tanji N, Yamamoto H. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma treated with total en bloc spondylectomy for 2 consecutive lumbar vertebrae resulted in continuous disease-free survival for more than 5 years— Case report. Spine. 2006;31:E231–E236. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000210297.02677.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo DJ, Jun JK, Kim SM. Total en bloc lumbar spondylectomy of follicular thyroid carcinoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45:188–191. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.45.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quraishi NA, Gokaslan ZL, Boriani S (2010) The surgical management of metastatic epidural compression of the spinal cord. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92:1054–1060. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.22296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Malhotra NR, Shaffrey CI. Intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:2167–2179. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f6f0d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thuet ED, Padberg AM, Raynor BL, Bridwell KH, Riew KD, Taylor BA, Lenke LG. Increased risk of postoperative neurologic deficit for spinal surgery patients with unobtainable intraoperative evoked potential data. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2094–2103. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000178845.61747.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imani F, Jafarian A, Hassani V, Khan ZH. Propofol-alfentanil vs propofol-remifentanil for posterior spinal fusion including wake-up test. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:583–586. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]