Abstract

Second heart field (SHF) progenitors perform essential functions during mammalian cardiogenesis. We recently identified a population of cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) in zebrafish expressing latent TGFβ-binding protein 3 (ltbp3) that exhibits several defining characteristics of the anterior SHF in mammals. However, ltbp3 transcripts are conspicuously absent in anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM), where SHF progenitors are specified in higher vertebrates. Instead, ltbp3 expression initiates at the arterial pole of the developing heart tube. Because the mechanisms of cardiac development are conserved evolutionarily, we hypothesized that zebrafish SHF specification also occurs in the ALPM. To test this hypothesis, we Cre/loxP lineage traced gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM populations predicted to contain SHF progenitors, based on evolutionary conservation of ALPM patterning. Traced cells were identified in SHF-derived distal ventricular myocardium and in three lineages in the outflow tract (OFT). We confirmed the extent of contributions made by ALPM nkx2.5+ cells using Kaede photoconversion. Taken together, these data demonstrate that, as in higher vertebrates, zebrafish SHF progenitors are specified within the ALPM and express nkx2.5. Furthermore, we tested the hypothesis that Nkx2.5 plays a conserved and essential role during zebrafish SHF development. Embryos injected with an nkx2.5 morpholino exhibited SHF phenotypes caused by compromised progenitor cell proliferation. Co-injecting low doses of nkx2.5 and ltbp3 morpholinos revealed a genetic interaction between these factors. Taken together, our data highlight two conserved features of zebrafish SHF development, reveal a novel genetic relationship between nkx2.5 and ltbp3, and underscore the utility of this model organism for deciphering SHF biology.

Keywords: Gata4, Heart development, Lineage tracing, Nkx2.5, Second heart field, Zebrafish

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart defects arise when genetic and/or environmental perturbations undermine normal cardiac development (reviewed by Bruneau, 2008; Epstein, 2010; Mahler and Butcher, 2011; Srivastava and Olson, 2000). As a class, they cause significant mortality during all stages of human life (Roger et al., 2012). The myocardium of the four-chambered vertebrate heart derives from two populations of cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), termed the first and second heart fields (FHF and SHF) (reviewed by Dyer and Kirby, 2009; Kelly, 2012; Vincent and Buckingham, 2010). The FHF and SHF are co-specified bilaterally in anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM) as naïve mesodermal cells initiate expression of several cardiac transcription factors, including nkx2.5 (Prall et al., 2007). The FHF differentiates within the ALPM, migrates to the midline and forms the myocardial layer of the linear heart tube, the embryonic precursor to the mammalian left ventricle. By contrast, the medially positioned SHF remains undifferentiated in the ALPM and relocates to midline pharyngeal mesoderm in a region between and including the poles of the nascent heart tube. At this stage, SHF progenitors proliferate, but also differentiate and accrete new myocardium to the poles of the heart tube to support its elongation. Through this process, the majority of primitive atrial and right ventricular myocardium are accreted to the venous and arterial poles, respectively. After accreting the primitive right ventricle, the SHF (or secondary heart field in avians) contributes differentiated lineages to the OFT, including proximal myocardium and distal smooth muscle (Grimes et al., 2010). All in all, SHF progenitors are multipotent, late-differentiating progenitor cells responsible for building the atria, right ventricle and embryonic OFT of the four-chambered vertebrate heart.

Severe defects in SHF development cause embryonic lethality owing to compromised production of the atria, right ventricle and embryonic OFT (Cai et al., 2003; Ilagan et al., 2006; Prall et al., 2007; von Both et al., 2004). Although intermediate SHF defects are compatible with birth, they can disrupt proper elongation, rotation and alignment of the OFT, leading to anomalous connections between the ventricles and great arteries after OFT septation (Bajolle et al., 2006; Ward et al., 2005).

The homeobox protein Nkx2.5 controls several aspects of cardiac developmental biology, and NKX2.5 mutations are associated with human congenital heart disease (Benson et al., 1999; Elliott et al., 2003; McElhinney et al., 2003; Schott et al., 1998). In mouse embryos, Nkx2.5 is expressed in both FHF and SHF cells within the ALPM (Stanley et al., 2002). Nkx2.5-null mice exhibit mid-gestation embryonic lethality owing to compromised SHF proliferation and accretion of RV and OFT segments to the heart tube (Prall et al., 2007).

Although initially described in higher vertebrates, a SHF was recently reported to make significant cellular contributions to the two-chambered zebrafish heart. The existence of a zebrafish SHF was inferred originally from cardiomyocyte proliferation, developmental timing and photoconversion assays (de Pater et al., 2009). In 2011, three reports described the zebrafish SHF as a population of CPCs contiguous with the arterial pole of the linear heart tube (Hami et al., 2011; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). The zebrafish SHF expresses homologs of CPC markers from higher vertebrates (nkx2.5, mef2c and isl1) but not the terminal differentiation marker cmlc2 (Hami et al., 2011; Hinits et al., 2012; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Witzel et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2011). We discovered that transcripts encoding latent TGFβ binding protein 3 (ltbp3) mark the zebrafish SHF, and we used Cre/loxP lineage tracing of ltbp3+ cells to delineate the cardiac descendants of the zebrafish SHF (Zhou et al., 2011). ltbp3+ cells traced to the distal half (relative to blood flow) of the ventricular myocardium and to three lineages in the OFT, including myocardium, endocardium and Eln2+ smooth muscle precursors. As predicted, perturbations to the zebrafish SHF manifest as developmental failures of SHF-derived structures, the most obvious being reductions in distal ventricular cardiomyocytes and OFT smooth muscle (de Pater et al., 2009; Hami et al., 2011; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011).

A fate map of the zebrafish ALPM revealed that myocardial progenitors reside in its posterior region (gata4+, hand2+) with atrial and ventricular progenitors inhabiting the lateral (nkx2.5-) and medial segments (nkx2.5+), respectively (Schoenebeck et al., 2007). In this way, mediolateral patterning of the ALPM heart-forming region is conserved with higher vertebrates (Abu-Issa and Kirby, 2007). We hypothesized that the cellular composition of the zebrafish ALPM would also be conserved and include medially specified SHF progenitors distinguished by unique genetic markers (Cai et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2001). However, the specific SHF marker ltbp3 is absent in the ALPM, instead becoming detectable at the arterial pole of the forming heart tube after midline migration of the heart field (Zhou et al., 2011). These apparent species-specific differences in the spatiotemporal expression patterns of SHF-restricted markers suggest that: (1) ltbp3 expression does not coincide with SHF specification in the zebrafish ALPM; or (2) SHF specification in zebrafish occurs at a later developmental stage in pharyngeal mesoderm.

Initial evidence to favor the former explanation was provided by a recent dye-tracing study demonstrating that at least some SHF myocardial and smooth muscle progenitors reside in the zebrafish ALPM (Hami et al., 2011). Here, we extend the dye tracing experiments of Hami et al. by performing genetic lineage-tracing studies of the zebrafish ALPM. Through these analyses, we characterized the full spectrum of cardiac derivatives and the molecular identity of SHF progenitors specified within the ALPM. Specifically, using an inducible Cre/loxP strategy, we discovered that gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM progenitors give rise to SHF-derived distal ventricular myocardium and OFT lineages. As a complementary approach, we performed Kaede fate mapping of nkx2.5+ cells within the ALPM and learned that the large majority of, and probably all, SHF progenitors for the ventricle and OFT are specified within the posterior and medial nkx2.5+ region of the gata4+ ALPM. Furthermore, we tested the hypothesis that nkx2.5 plays an evolutionarily conserved role during SHF development in zebrafish. Specifically, we discovered that embryos injected with an antisense nkx2.5 morpholino exhibit SHF phenotypes attributable to defective proliferation of SHF progenitors. Last, we uncovered a novel genetic interaction between nkx2.5 and ltbp3 during SHF-mediated OFT development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish husbandry and strains

Zebrafish were maintained as described previously (Westerfield, 2000). Animal protocols were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The following zebrafish strains were used: wild-type AB; wild-type TuAB; Tg(-14.8gata4:ERCreER)pd39 (Kikuchi et al., 2010); TgBAC(-25ltbp3:TagRFP2Acre)fb1 (Zhou et al., 2011); Tg(cmlc2:CSY)fb2 (Zhou et al., 2011); TgBAC(eln2:CSY)fb4 (Zhou et al., 2011); TgBAC(kdrl:CSY)fb3 (Zhou et al., 2011); Tg(cmlc2:dsRed2-nuc)f2 (Mably et al., 2003); [Tg(-3.5ubi:loxP-EGFP-loxP-mCherry)III]cz1701 (Mosimann et al., 2011); Tg(-36nkx2.5:ZsYellow)fb7 (Zhou et al., 2011); Tg(tbp:GAL4; cmlc2:cerulean)f13 (van Ham et al., 2010) and Tg(UAS:secA5-YFP; cmlc2:mcherry)f12 (van Ham et al., 2010). To generate the TgBAC(-36nkx2.5:ERCreER)fb8 driver and TgBAC(-36nkx2.5:Kaede)fb9 photoconvertible strains, BAC DKEY-9I15 was modified and trimmed as described (Zhou et al., 2011), except with protein-coding sequences for ERCreER (Matsuda and Cepko, 2007) and Kaede (Ando et al., 2002), respectively. Germline transmission of BAC transgenes was achieved through co-injection of Tol2 transposase (Suster et al., 2009).

Genetic lineage tracing

Zebrafish hemizygous for a single driver transgene or single reporter transgene were incrossed and their embryos arrayed 30 per well in 12-well plates. For all treatments, embryos were incubated in 1 ml embryo medium (E3) containing 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 10 μM. For mock treatments, embryos were incubated in 1 ml E3 containing an equivalent volume of 100% ethanol, the solvent for the 10 mM (1000×) 4-OHT stock. For continuous 4-OHT exposures, treatments were initiated at 75% epiboly (8 hpf) and at two subsequent time points (24 and 48 hpf), embryos were washed 10 times with 50 ml E3 and returned to the wells with fresh dilutions of 4-OHT. For pulsed 4-OHT exposure, treatments were initiated at 75% epiboly (8 hpf). At the 14- to 16-somite stage, embryos were washed 10 times with 50 ml E3 and returned to the wells with E3 alone. Embryos were fixed at 72 hpf (for myocardial and ubiquitous lineage tracing) or at 6 dpf (for OFT endothelial and smooth muscle cell lineage tracing) in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 1 hour, rinsed in 1×PBS plus 1% Tween for 30 minutes, and transferred to 1×PBS prior to analysis and imaging. Embryos carrying the lineage-specific reporter transgene were identified visually by cardiac AmCyan and/or ZsYellow expression. Embryos carrying the ubiquitous reporter transgene were identified by whole embryo GFP expression. The numbers of double transgenic embryos in each clutch were calculated based on Mendelian inheritance of the driver transgene.

Microscopy and imaging

Microscopy and imaging were performed as described (Zhou et al., 2011). Prior to imaging, embryos were embedded in 1.2% low melting point agarose (NuSieve GTG Agarose, Lonza) in 35 mm MatTek glass bottom Petri dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). Embedded embryos were immersed in 1× PBS prior to confocal imaging with a 40× water immersion objective. Z-stack confocal images were analyzed with ImageJ software (Abramoff et al., 2004). Cardiomyocyte nuclei in the atrium and ventricle were distinguished by the atrio-ventricular junction.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

In situ hybridization was performed with antisense ltbp3 and cmlc2 riboprobes as described previously (Zhou et al., 2011). Embryos were double stained with MF20 and α-Eln2 antibodies as described previously (Zhou et al., 2011).

Kaede photoconversion

Tg(nkx2.5:Kaede) embryos were photoconverted using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescent microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY), 20× objective, UV filter (Nikon UV-2E/C) and Lumen 200 Fluorescence Lumination System (Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA). At 14- to 16-somite stages, embryos were mounted in 0.9% low melting point agarose in 35 mm MatTek glass bottom Petri dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). Prior to photoconversion, embryos were imaged using a GFP filter. Immediately thereafter, embryos were exposed continually to UV light for 60 seconds and assessed visually for residual green fluorescence. As needed, embryos were exposed to UV light for an additional 20 seconds, generally sufficient for complete photoconversion. Photoconverted embryos were arrayed individually in six-well plates and incubated in the dark until 72 hpf, when they were imaged live by confocal microscopy. During imaging, embryos were anesthetized with Tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and treated with 2,3-butanedione 2-monoxime (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) to cease cardiac contractions.

Morpholino injections and mRNA rescue

One-cell stage embryos were injected with 2.5-3.5 ng of a previously validated antisense morpholino [anti-nkx2.5 splice MO (Targoff et al., 2008)] that inhibits pre-mRNA splicing of nkx2.5. Uninjected embryos were used as controls in all experiments. A full-length nkx2.5 cDNA was cloned into pCS2+ using In-Fusion cloning (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). mRNA was transcribed with SP6 polymerase after plasmid digestion with KpnI. Messenger RNA (200 pg) was injected into the yolks of embryos pre-injected with morpholino. At 72 hpf, embryos in each experimental group were scored based on OFT Eln2 staining. Embryos were categorized as ‘unaffected’ if a prominent Eln2 signal was visible in the OFT. Embryos were scored as ‘absent’ if no Eln2 signal was visible in the OFT. Embryos were scored as ‘reduced’ if a significant reduction in Eln2 staining was observed.

Three different combinations of morpholinos were co-injected into the yolks of one-cell stage embryos to test for a genetic interaction between ltbp3 and nkx2.5: (1) 0.6 ng ltbp3 MO [MOspl (Zhou et al., 2011)] plus 2.5 ng control MO (Vivo-Morpholino standard control oligo, Genetools, Philomath, OR, USA); (2) 0.6 ng control MO plus 2.5 ng nkx2.5 MO [anti-nkx2.5 splice MO; (Targoff et al., 2008)]; and (3) 0.6 ng ltbp3 MO plus 2.5 ng nkx2.5 MO. At 72 hpf, embryos were scored based on OFT Eln2 staining.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using Fast SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and primers for ltbp3 [Ltbp3F (5′-TCTGTGTTCACTCTGCAAGG-3′), Ltbp3R (5′-GTTTTGGTACTGTGAGGCTTG-3′)] and β-actin [β-ActinF (5′-ATCTTCACTCCCCTTGTTCAC-3′) and β-ActinR (5′-TCATCTCCAGCAAAACCGG-3′)]. To exclude notochord expression of ltbp3 from the analysis, anesthetized embryos were severed at the anterior tip of the notochord, and the posterior segments excluded. Three biological replicates were analyzed in triplicate.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 20 28-hpf control and morphant embryos using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Primers F1, R1 and R2 (Targoff et al., 2008) were used to amplify first-strand cDNAs for unspliced (F1/R1) or spliced (F1/R2) nkx2.5 transcripts. Amplification of the 18S rRNA (Feng et al., 2010) was used as a loading control.

EdU protocol

SHF proliferation in Tg(nkx2.5:ZsYellow) embryos was assessed with the Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as previously described (Mahler et al., 2010) with some modifications. EdU incorporation (red fluorescence) and ZsYellow protein expression (green fluorescence) were detected by double immunostaining. A detailed protocol is available upon request. Double-positive cells in the heart tube were identified as red fluorescent nuclei surrounded by green cellular fluorescence in z-stack confocal slices.

Statistics

P-values were calculated using an unpaired Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Inducible Cre/loxP lineage tracing reveals specification of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF progenitors in the zebrafish ALPM

Based on similarities in ALPM patterning between zebrafish (Schoenebeck et al., 2007) and higher vertebrates (Abu-Issa and Kirby, 2007), we hypothesized that the posterior and medial nkx2.5+ region of the gata4+ ALPM contains SHF progenitors that will come to express ltbp3 transcripts after relocating to midline pharyngeal mesoderm. We tested this hypothesis by evaluating the respective contributions of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM progenitors to SHF-derived regions of the ventricle and OFT (Zhou et al., 2011) using inducible Cre/loxP-mediated lineage tracing.

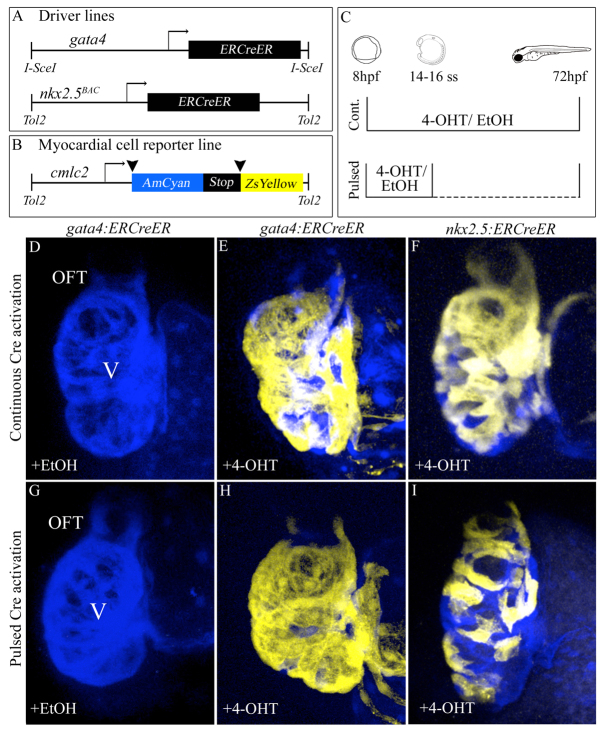

To delineate the myocardial fates of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM progenitors, we analyzed double transgenic embryos carrying an inducible Cre driver transgene [either Tg(gata4:ERCreER) (Kikuchi et al., 2010) or Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER) (Fig. 1A)] and the Cre-responsive myocardial switch reporter Tg(cmlc2:loxPAmCyanSTOPloxPZsYellow) [abbreviated Tg(cmlc2:CSY) (Fig. 1B) (Zhou et al., 2011)]. The cis-regulatory elements contained in the driver transgenes direct expression of heterologous proteins, in this case 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT)-inducible Cre recombinase (ERCreER), to gata4+ (Heicklen-Klein and Evans, 2004; Kikuchi et al., 2010) or nkx2.5+ (supplementary material Fig. S1) cells in the ALPM. The switch reporter expresses the AmCyan fluorescent protein in all myocardial cells. However, if Cre activity is introduced into myocardial progenitor cells, or their descendants, then reporter recombination will occur, and those myocardial cells carrying the recombined transgene will initiate expression of the ZsYellow reporter protein (Zhou et al., 2011).

Fig. 1.

Specification of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF myocardial progenitors in the zebrafish ALPM. (A,B) Driver and reporter transgenes employed for inducible Cre/loxP-mediated myocardial lineage tracing of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM cells. (C) Experimental strategy. Double transgenic embryos were exposed continuously (’Cont.’) to 10 μM 4-OHT or solvent alone (ethanol) between 8 and 72 hpf. Alternatively, embryos were exposed transiently (’Pulsed’) to 4-OHT or ethanol between 8 hpf (75% epiboly) and the 14- to 16-somite stages prior to extensive rinsing with embryo medium (E3). All embryos were analyzed and imaged at 72 hpf for cardiac ZsYellow reporter fluorescence. (D,G) Hearts in Tg(gata4:ERCreER); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos treated continuously (D) or transiently (G) with ethanol. (E,H) Hearts in Tg(gata4:ERCreER); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos treated continuously (E) or transiently (H) with 4-OHT. (F,I) Hearts in Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos treated continuously (F) or transiently (I) with 4-OHT. Hpf, hours post-fertilization; ss, somite stage; V, ventricle; OFT, outflow tract; EtOH, ethanol; 4-OHT, 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

To confirm that reporter recombination is dependent on 4-OHT-mediated Cre induction, we mock treated Tg(gata4:ERCreER); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) or Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos with ethanol, the solvent for 4-OHT, transiently between 8 hours post-fertilization (hpf) and the 14- to 16-somite stages (ss) (16-17 hpf) or continuously between 8 and 72 hpf (Fig. 1C). As expected, ZsYellow fluorescence was not observed under these experimental conditions (Fig. 1D,G; Table 1). Next, we confirmed the inducibility of ERCreER activity by exposing embryos continuously to 4-OHT between 8 and 72 hpf. Using this strategy, we anticipated labeling the entire ventricle because the gata4 (Heicklen-Klein and Evans, 2004) and nkx2.5 promoters (Chen and Fishman, 1996; Yelon et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 2011) remain active in the heart tube beyond ALPM stages. Accordingly, in both experimental groups, continuous 4-OHT exposure caused the large majority of ventricular myocardial cells to express ZsYellow, including those in the SHF-derived distal segment (Fig. 1E,F; Table 1). These data demonstrate that 4-OHT effectively induces ERCreER activity in both experimental groups of embryos and confirms the traceability of SHF-derived myocardium using these combinations of driver and reporter transgenes. Nonetheless, owing to persistent gata4 and nkx2.5 promoter activity beyond ALPM stages, continuous induction of ERCreER activity cannot address the question of SHF specification in the ALPM.

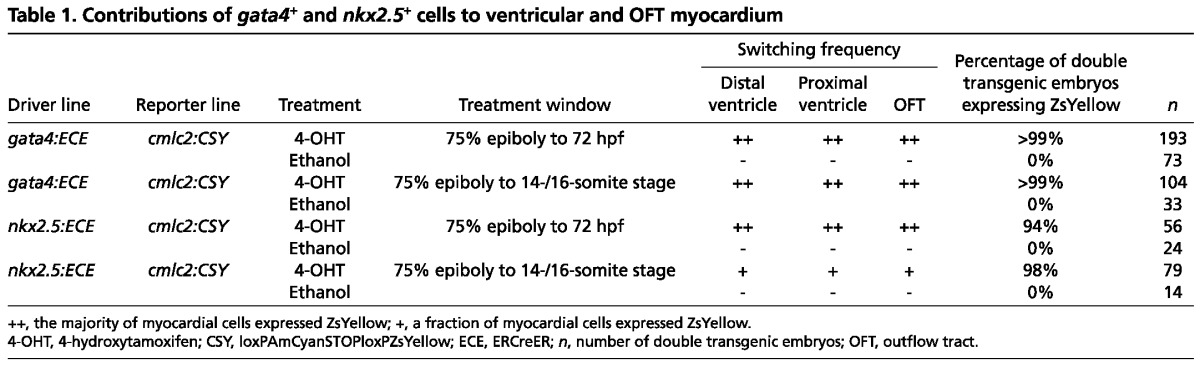

Table 1.

Contributions of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ cells to ventricular and OFT myocardium

Therefore, we induced Cre activity transiently in gata4+ and nkx2.5+ ALPM cells between 75% epiboly (8 hpf) and the 14- to 16-somite stages (Fig. 1C). This developmental window encompasses establishment of the ALPM (Kimmel et al., 1995) and initiation of myocardial differentiation (Yelon et al., 1999). At 14- to 16-somite stages, embryos were rinsed extensively with embryo medium to remove residual 4-OHT and allowed to develop until 72 hpf when they were evaluated for cardiac ZsYellow expression in SHF-derived structures (Zhou et al., 2011). Following transient Cre induction in gata4+ progenitors, we observed robust ZsYellow labeling of the entire ventricle, including the SHF-derived distal segment (Fig. 1H; Table 1). Furthermore, we observed ZsYellow labeling of cardiomyocytes in the proximal OFT (Fig. 1H; Table 1). These data demonstrate that SHF ventricular and OFT myocardial progenitors reside within the gata4+ ALPM.

Following transient Cre induction in nkx2.5+ ALPM cells, we observed indiscriminate partial labeling of the ventricle and OFT (Fig. 1I; Table 1). Both FHF-derived (proximal) and SHF-derived (distal) ventricular myocardial cells appeared to be labeled with equal frequency across all embryos we analyzed. This observation demonstrates that at least a fraction of SHF myocardial progenitors reside in the nkx2.5+ domain of the larger gata4+ ALPM.

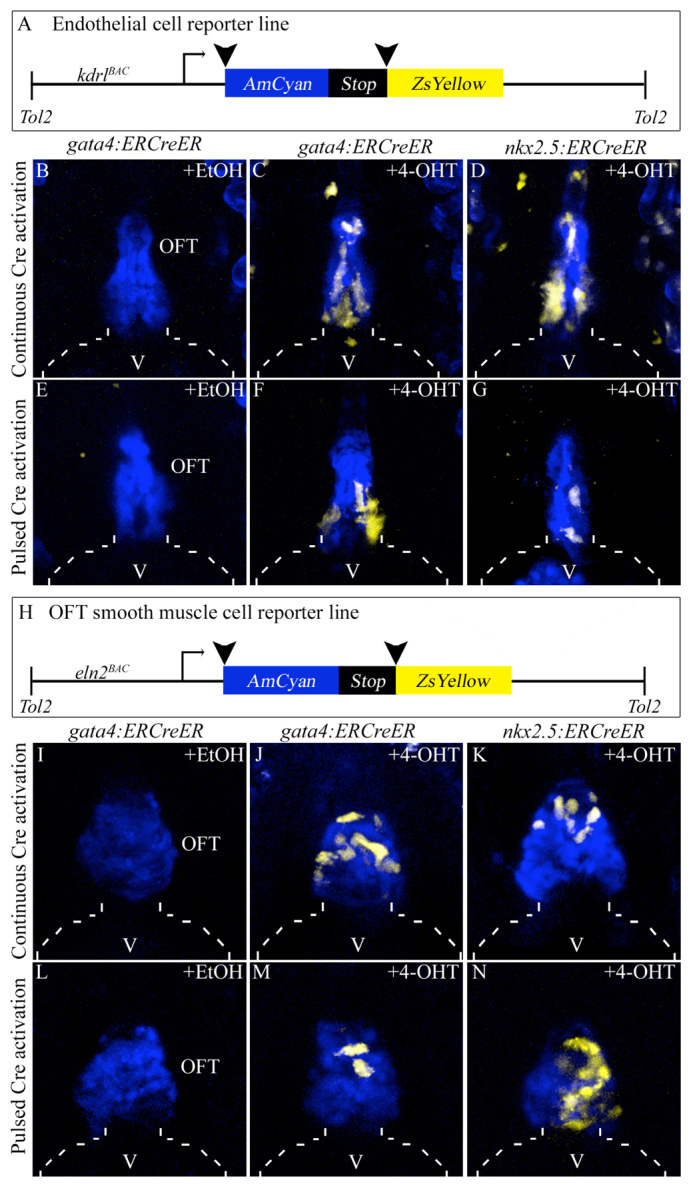

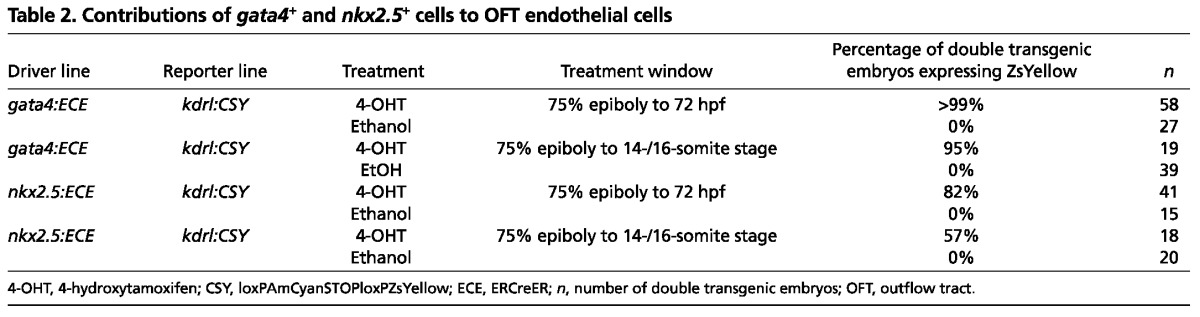

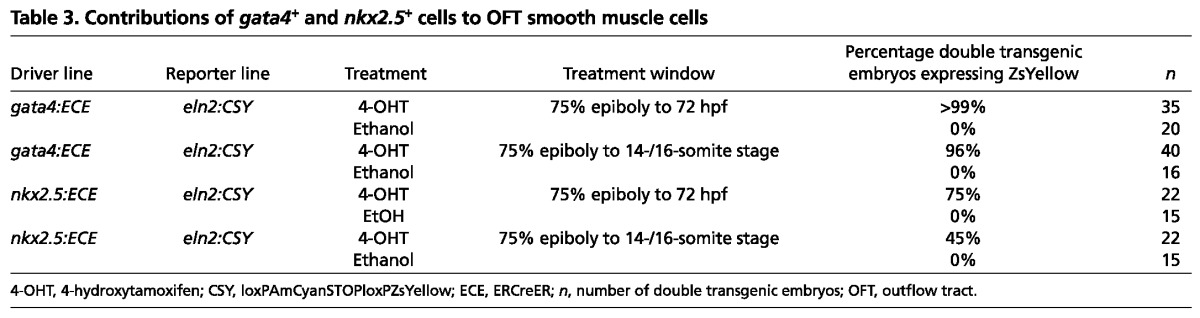

gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF progenitors for OFT endothelial and smooth muscle lineages are specified within the ALPM

Next, we tested the hypothesis that two additional SHF-derived lineages, endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the OFT (Zhou et al., 2011), also derive from gata4+ and nkx2.5+ regions of the zebrafish ALPM. To achieve this, we generated four experimental groups of embryos, each with different pair-wise combinations of driver [either Tg(gata4:ERCreER) or Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER)] (Fig. 1A) and reporter [either Tg(kdrl:CSY) or Tg(eln2:CSY)] (Fig. 2A,H) transgenes. The Tg(kdrl:CSY) and Tg(eln2:CSY) transgenes report contributions of Cre-expressing cells to OFT endothelial and smooth muscle lineages, respectively (Zhou et al., 2011). As expected, continuous and pulsed ethanol treatments of each experimental group failed to induce ZsYellow expression (Fig. 2B,E,I,L; Tables 2, 3). By contrast, continuous and pulsed treatments of all experimental groups with 4-OHT caused a modest proportion of OFT endothelial or smooth muscle cells to express the ZsYellow reporter protein (Fig. 2C,D,F,G,J,K,M,N; Tables 2, 3), indicating that at least a fraction of OFT cells derive from gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF progenitors specified in the ALPM. Across all embryos in any given experimental group, the labeled OFT cells appeared randomly distributed.

Fig. 2.

Specification of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF endothelial and smooth muscle progenitors in the zebrafish ALPM. (A) Schematic of the endothelial/endocardial reporter transgene. (B-G) OFT regions of 6 dpf double transgenic embryos treated continuously (8-72 hpf; B-D) or transiently (75% epiboly to 14- to 16-somite stages; E-G) with ethanol (B,E) or 4-OHT (C,D,F,G). (H) Schematic of the OFT smooth muscle reporter transgene. (I-N) OFT regions of 6 dpf double transgenic embryos treated continuously (8-72 hpf; I-K) or transiently (75% epiboly to 14-16 ss; L-N) with ethanol (I,L) or 4-OHT (J,K,M,N). Broken lines outline the ventricle (V). EtOH, ethanol; OFT, outflow tract; 4-OHT, 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

Table 2.

Contributions of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ cells to OFT endothelial cells

Table 3.

Contributions of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ cells to OFT smooth muscle cells

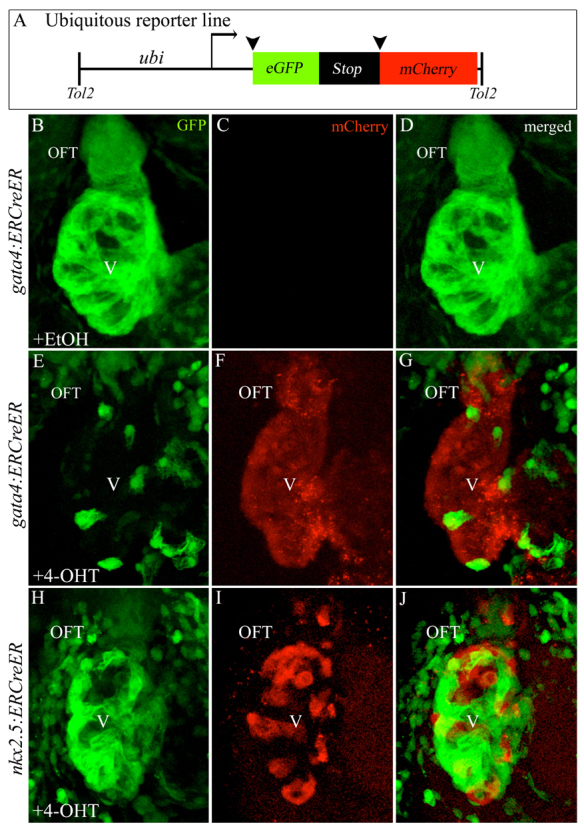

Ubiquitous reporter transgene confirms SHF progenitor specification in the ALPM

The unlabeled ventricular (Fig. 1I) and OFT (Fig. 2) cells we observed in lineage-specific tracing experiments might reflect inefficiencies inherent to the loxP reporter strains (Hans et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2008; Mosimann et al., 2011) and/or Cre driver lines (Hans et al., 2009). Alternatively, the unlabeled cells might derive from an alternative progenitor population.

Because different loxP reporter lines can exhibit variable sensitivities to Cre activity based on integration site (Mosimann et al., 2011), we repeated the pulsed tracing of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ cells using a highly sensitive ubiquitous reporter line [Tg(ubi:loxP-EGFP-loxP-mCherry)III, abbreviated Tg(ubi:Switch)] (Mosimann et al., 2011). As anticipated, pulsed exposure of Tg(gata4:ERCreER), Tg(ubi:Switch) or Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER), Tg(ubi:Switch) embryos to ethanol failed to induce expression of the mCherry reporter protein (Fig. 3B-D; data not shown). By contrast, pulsed exposure of Tg(gata4:ERCreER), Tg(ubi:Switch) embryos to 4-OHT between 75% epiboly and the 14- to 16-somite stages caused a large majority of the ventricle to express the mCherry reporter protein (Fig. 3F), consistent with widespread ZsYellow labeling of the ventricular myocardium using the myocardial reporter strain (Fig. 1H). However, in the OFT, a much higher percentage of cells expressed mCherry (Fig. 3E-G) compared with the lineage-specific traces (Fig. 2F,M), indicating that the lineage-specific reporters underestimated the contributions made by gata4+ cells to the OFT. Taken together, these data suggest that, at a minimum, a large majority of the zebrafish OFT derives from gata4+ cells in the ALPM.

Fig. 3.

Ubiquitous reporter transgene corroborates specification of gata4+ and nkx2.5+ SHF progenitors in the ALPM. (A) Ubiquitous reporter transgene. (B-J) Hearts in 72 hpf double transgenic embryos treated transiently (75% epiboly to 14- to 16-somite stages) with ethanol [B-D; n=0/8 double transgenic embryos with cardiac mCherry reporter fluorescence; for nkx2.5 trace (hearts not shown), n=0/17 with reporter fluorescence] or 4-OHT (E-J) imaged in the green (B,E,H) and red (C,F,I) channels. Merged images are shown in D,G,J. n=18/18 double transgenic embryos with cardiac mCherry reporter fluorescence for E-G. n=15/15 with reporter fluorescence for H-J. OFT, outflow tract; V, ventricle; EtOH, ethanol; 4-OHT, 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

Following transient exposure of Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER); Tg(ubi:Switch) embryos to 4-OHT, only partial mCherry reporter labeling of the ventricle and OFT was observed (Fig. 3H-J), consistent with the partial ZsYellow labeling we observed using the lineage-restricted reporters (Fig. 1I; Fig. 2G,N). Because Cre tracing efficiencies can depend on 4-OHT dose (Hans et al., 2009), we attempted to increase the proportions of labeled cells by raising the treatment dose of 4-OHT. Unfortunately, higher 4-OHT doses (>10 μM) proved toxic to embryos (B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B., unpublished). Therefore, despite achieving maximal Cre induction in Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER) embryos carrying a highly sensitive reporter, we failed to observe more than partial labeling of the ventricle and OFT (B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B., unpublished).

These findings raise two possibilities: (1) that all SHF-derived cells do in fact come from nkx2.5+ cells in the ALPM but the driver strain we isolated was rate-limiting for maximal labeling, perhaps owing to a position effect; or (2) that the unlabeled cells derive from an nkx2.5- cell population. In an attempt to rule out the first possibility, we isolated another Tg(nkx2.5:ERCreER) strain. Unfortunately, compared with the original strain, the second insertion produced fewer labeled cells under the same conditions (B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B., unpublished).

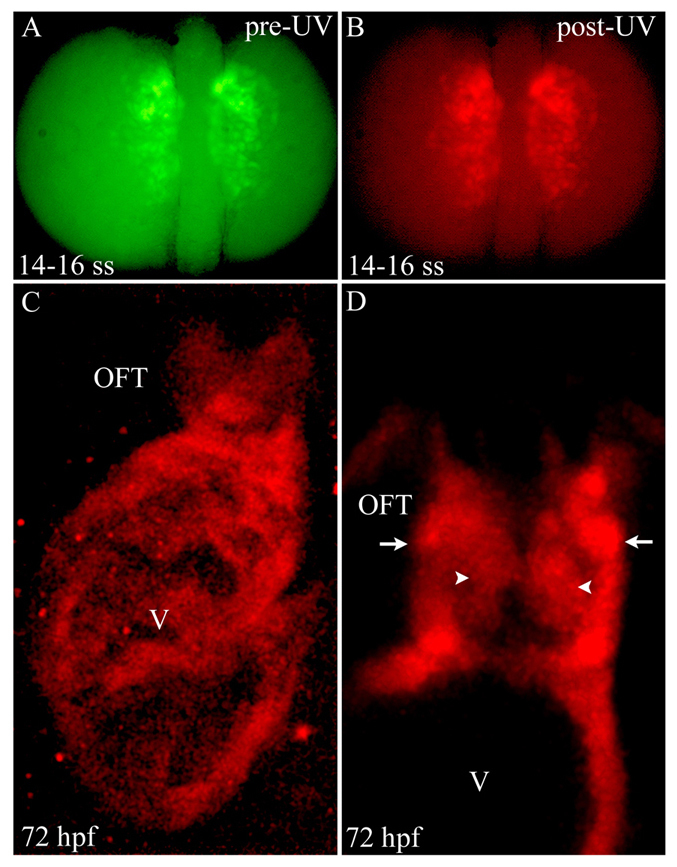

Photoconversion of nkx2.5+ cells in the ALPM reveals extensive contributions to SHF-derived structures

In another attempt to distinguish these alternatives, we fate mapped ALPM nkx2.5+ cells using Kaede photoconversion, a complementary approach to Cre/loxP lineage tracing not dependent on inducible enzymatic activity and reporter recombination. To achieve this, we generated a BAC transgenic strain, Tg(nkx2.5:Kaede), expressing Kaede protein under the transcriptional control of the same cis-regulatory elements used previously (Zhou et al., 2011) (supplementary material Fig. S1). In Tg(nkx2.5:Kaede) embryos, the unconverted green Kaede protein was expressed robustly in the ALPM by 14- to 16-somite stages (Fig. 4A). At the same developmental stage (14-16 somites), we used UV light to completely and permanently photoconvert the Kaede protein from green to red fluorescence (Fig. 4B). UV-treated embryos were analyzed at 72 hpf for the distribution of persistent red Kaede protein in the ventricle and OFT. In a majority of embryos, red fluorescence was observed relatively uniformly in the ventricle and OFT (Fig. 4C,D), reflecting a higher proportion of labeled cells when compared with the Cre/loxP traces (Fig. 1I; Fig. 2G,N; Fig. 3I). These data suggest that the Cre-based tracing underestimated the fraction of ventricular and OFT cells derived from nkx2.5+ progenitors. Given the uniform labeling of the distal ventricle and OFT following Kaede photoconversion, we conclude that the large majority of, if not all, SHF progenitors are specified in the ALPM and express nkx2.5.

Fig. 4.

Photoconversion of nkx2.5+ cells in the ALPM reveals widespread contributions to SHF-derived structures. (A,B) Dorsal images of a 14- to 16-somite stage Tg(nkx2.5:Kaede) embryo before (A) and after (B) photoconversion with ultraviolet (UV) light. (C) Confocal z-stack image of the ventricle (V) and OFT at 72 hpf. (D) Confocal slice of the OFT. Arrowheads and arrows highlight endothelial and smooth muscle precursor cells in the OFT, respectively. Six out of eight photoconverted embryos exhibited red Kaede protein throughout the ventricle and OFT. ss, somite stage; OFT, outflow tract; hpf, hours post-fertilization.

Inhibition of zebrafish Nkx2.5 function elicits SHF phenotypes

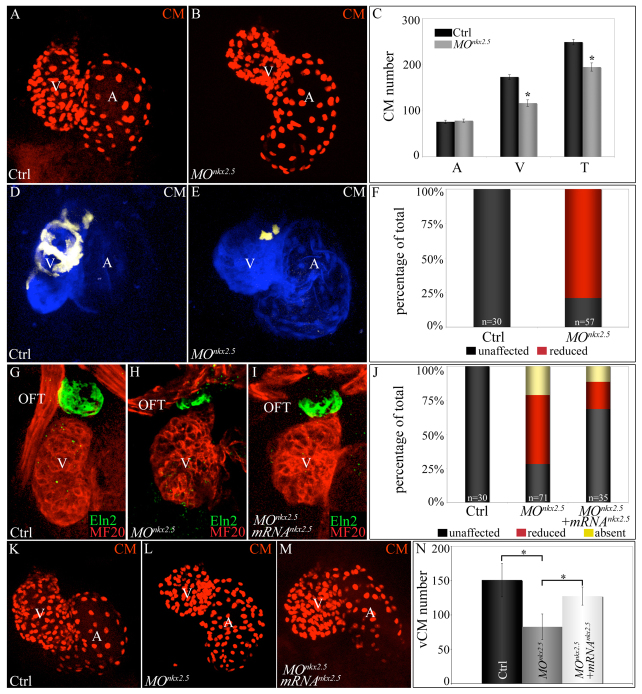

Mouse embryos lacking nkx2.5 function die in utero from prominent SHF defects owing to compromised progenitor proliferation (Prall et al., 2007). To determine whether Nkx2.5 is similarly required for SHF development in zebrafish, we analyzed nkx2.5 morphant embryos for manifestations of SHF defects, including deficits in distal ventricular myocardium and OFT smooth muscle.

In the absence of an nkx2.5 null allele, we knocked down nkx2.5 by injecting one-cell stage embryos with a previously validated antisense morpholino that effectively inhibits splicing of the nkx2.5 mRNA (supplementary material Fig. S2) (Targoff et al., 2008). Consistent with previous findings, we observed that morphant atria appeared somewhat misshapen and the ventricles were smaller (Fig. 5A,B). To determine whether the chamber morphology phenotypes reflected abnormal cardiomyocyte numbers, we counted fluorescent cardiomyocyte nuclei in control and nkx2.5 morphant embryos carrying the Tg(cmlc2:dsRec2-nuc) transgene (Mably et al., 2003). Although the number of atrial cells was unaffected in the morphants, the number of ventricular cells was significantly reduced by 31% (Fig. 5A-C). To determine whether SHF-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes were preferentially affected in nkx2.5 morphants, we injected the nkx2.5 morpholino into Tg(ltbp3:TagRFP2Acre); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos, which express ZsYellow reporter protein in SHF-derived distal ventricular myocardium (Zhou et al., 2011). Whereas in control embryos, ZsYellow expression was seen in the distal half of the ventricular myocardium (Fig. 5D,F), morphant ventricles exhibited a significantly reduced number of cells labeled with ZsYellow (Fig. 5E,F), consistent with the conclusion that the distal SHF-derived segment of ventricular myocardium is compromised specifically in nkx2.5 morphant embryos.

Fig. 5.

Morpholino-mediated inhibition of nkx2.5 pre-mRNA splicing elicits SHF phenotypes. (A-C) nkx2.5 morphants display ventricular cardiomyocyte deficits. z-stack images of hearts in control (A) and nkx2.5 morpholino-injected (B) Tg(cmlc2:dsRed2-nuc) embryos imaged at 72 hpf. (C) Average numbers of atrial (A), ventricular (V) and total (T) cardiomyocytes in control (n=6) and morphant (n=11) embryos. Error bars represent one s.d. *P<0.001. (D-F) SHF-derived ventricular myocardium is specifically reduced in nkx2.5 morphants. Control (D) and morpholino-injected (E) Tg(ltbp3:TagRFP2Acre); Tg(cmlc2:CSY) embryos imaged in the blue and yellow channels (merged images shown) by confocal microscopy at 72 hpf. (F) The percentages of embryos with reduced ventricular ZsYellow expression. The n values are reported in the graph. (G-J) nkx2.5 morphants exhibit reductions in Eln2+ OFT cells, a phenotype partially rescued by co-injection of nkx2.5 mRNA. Control (G; unaffected), morphant (H; reduced) and mRNA-injected morphant (I; unaffected) embryos were co-stained at 72 hpf with MF20 and anti-Eln2 antibodies to label myocardium (red) and OFT smooth muscle (green), respectively. (J) Percentages of embryos with unaffected, reduced or absent Eln2 staining. The n values are reported in the graph. (K-N) Injection of nkx2.5 mRNA partially rescues the ventricular cardiomyocyte deficit in nkx2.5 morphants. Control (K), morphant (L) and mRNA-injected morphant (M) Tg(cmlc2:dsRed2-nuc) embryos imaged by confocal microscopy at 72 hpf. (N) Average numbers of ventricular cardiomyocytes (vCMs) in each experimental group (n=4 per cohort). Error bars represent one s.d. *P<0.05. CM, cardiomyocytes; V, ventricle; A, atrium; OFT, outflow tract; Ctrl, control; MO, morpholino.

We also evaluated nkx2.5 morphants for defects in Eln2+ smooth muscle precursor cells in the OFT (Grimes et al., 2010; Grimes et al., 2006; Miao et al., 2007). These cells are derived from gata4+, nkx2.5+ and hand2+ SHF cells within the ALPM (Figs 2, 3, 4) (Hami et al., 2011), and at least partially from ltbp3+ SHF cells within pharyngeal mesoderm (Zhou et al., 2011). Furthermore, defects in the formation of this cell population appear to be a general feature of SHF phenotypes in the zebrafish (Hami et al., 2011; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). Whereas control embryos exhibited robust Eln2+ signals in the OFT, nkx2.5 morphants exhibited either reduced or absent Eln2 staining in the same region (Fig. 5G,H,J). Taken together, the combination of cardiomyocyte reductions localized to the distal ventricle and OFT smooth muscle defects indicates that nkx2.5 morphants harbor phenotypes characteristic of SHF perturbations.

To address morpholino specificity, we attempted to rescue the OFT and ventricular cardiomyocyte deficiencies in nkx2.5 morphants by co-injecting embryos with morpholino and nkx2.5 mRNA. Co-injecting the mRNA partially rescued the OFT defect as the percentage of phenotypic animals decreased from 72% to 31% (Fig. 5G-J). Similarly, mRNA co-injection boosted ventricular cardiomyocyte numbers by 53% (Fig. 5K-N), indicating a partial rescue. Taken together, these observations support specificity of the nkx2.5 morpholino.

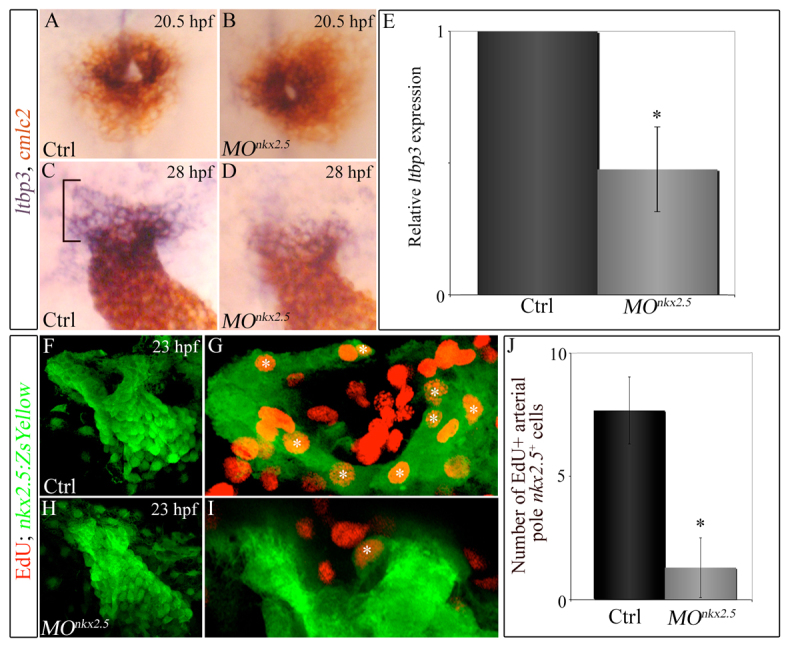

The cardiac phenotype we documented in nkx2.5 morphants virtually phenocopies ltbp3 morphants (Zhou et al., 2011), which raises the possibility that nkx2.5 and ltbp3 reside in a common genetic pathway. Most likely, nkx2.5 functions upstream of ltbp3 based on the observation that SHF progenitors express nkx2.5 in the ALPM prior to initiating expression of ltbp3 in pharyngeal mesoderm [this study and (Zhou et al., 2011)]. To test this hypothesis, we performed in situ hybridization for ltbp3 transcripts in nkx2.5 morphants. At the 23-somite stage (20.5 hpf), when ltbp3 expression initiates in the cardiac cone, no obvious difference in ltpb3 expression was observed between control and morphant embryos. (Fig. 6A,B), suggesting that SHF progenitors were specified properly in nkx2.5 morphants. However, after the linear heart tube is established (28 hpf), we observed a qualitative decrease in the intensity and breadth of ltbp3 expression at the heart tube arterial pole (Fig. 6C,D). Using quantitative PCR, we learned that nkx2.5 morphants express approximately half the number of ltbp3 transcripts (Fig. 6E), suggesting that nkx2.5 is required to maintain ltbp3 expression.

Fig. 6.

Knocking down nkx2.5 compromises arterial-pole ltbp3 expression and SHF proliferation. (A-D) Double in situ hybridization of cmlc2 and ltbp3 transcripts in control (A,C) and morphant (B,D) embryos at 20.5 (23-somite stage, cardiac cone stage; n=20, control; n=32, morphant) and 28 (linear heart tube stage; n=20, control; n=30/48 morphants) hpf. Bracket highlights non-myocardial ltbp3+ SHF progenitors. (E) Graph showing the average relative abundance of ltbp3 transcripts in morphant compared with control embryos at 28 hpf determined by quantitative PCR. Error bar represents one s.d., *P<0.05. (F-J) nkx2.5 morphants exhibit reductions in proliferating arterial-pole nkx2.5+ SHF cells. At 23 hpf, control and morphant Tg(nkx2.5:ZsYellow) embryos were double immunostained for incorporated EdU (red) and ZsYellow protein (green). Confocal z-stack images of heart tube regions in control (F,G) and morphant (H,I) embryos captured through green and red filters. (F,H) Flattened z-stack images (green channel only) of representative control (F) and morphant (H) heart tubes. (G,I) Arterial poles of heart tubes shown in F and H. Three contiguous confocal slices (red and green channels merged) from F and H were flattened. White asterisks mark double-positive cells (EdU+ red nuclei surrounded by ZsYellow+ green cellular fluorescence). (H) Average numbers of double-positive cells in control and morphant heart tubes. n=6 embryos per experimental group. Error bars represent one s.d., *P<0.0001. hpf, hours post-fertilization; Ctrl, control; MO, morpholino.

Next, we sought to determine the mechanism by which nkx2.5 is required for SHF development. To achieve this, we analyzed nkx2.5 morphants for evidence of apoptosis overlapping spatially and temporally with the loss of ltbp3 expression in the SHF. Specifically, we injected the nkx2.5 morpholino into secA5-YFP-expressing embryos that report apoptotic cells (van Ham et al., 2010). We found no evidence for SHF apoptosis in control or morphant embryos at cardiac cone (23 somite stage) or linear heart tube (24 hpf) stages (supplementary material Fig. S3), despite obvious reporter fluorescence in other embryonic regions, including the brain (not shown). Next, we used the thymidine analog EdU to measure proliferation of SHF progenitors in control and morphant Tg(nkx2.5:ZsYellow) embryos at 23 hpf. At this developmental stage, the heart is a nascent tube (Yelon et al., 1999) with non-myocardial nkx2.5+, ltbp3+ SHF progenitors residing at its arterial pole (Zhou et al., 2011). We detected double-positive (EdU+, ZsYellow+) cells predominantly in the arterial pole/SHF region of the developing nkx2.5+ heart tube (Fig. 6F-I). On average, control and morphant embryos harbored eight and one double-positive cells, respectively, in this region (Fig. 6G,I,J) demonstrating that SHF proliferation is compromised in the absence of Nkx2.5 function.

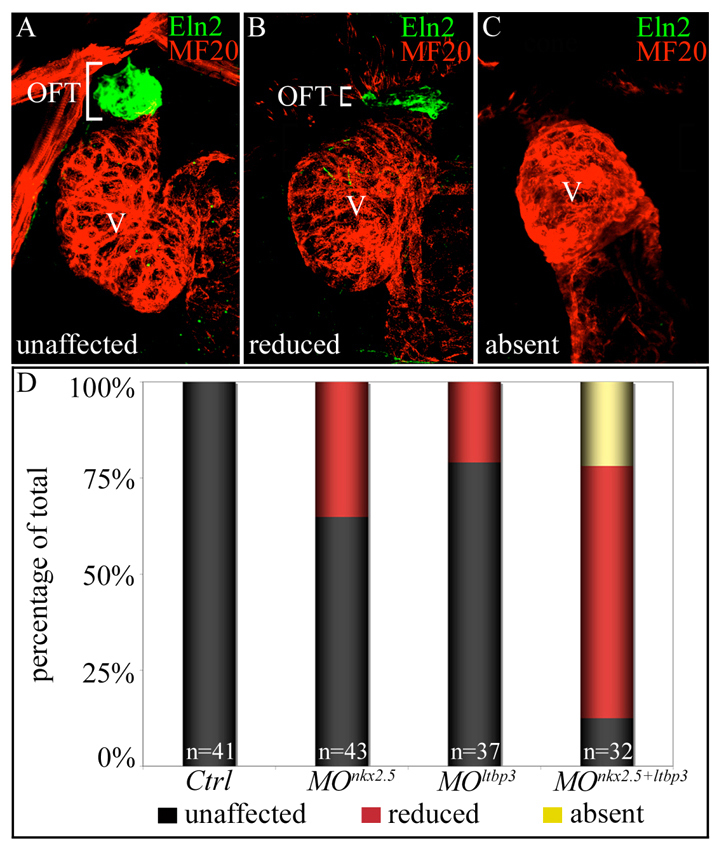

Because nkx2.5 and ltbp3 morphant embryos both show prominent SHF defects caused by compromised progenitor proliferation, we tested the hypothesis that nkx2.5 and ltbp3 interact genetically for optimal SHF development by injecting low doses of each morpholino either individually or together. When the morpholinos were injected individually, the majority of embryos in each experimental group exhibited wild-type Eln2 staining in the OFT (Fig. 7A,B,D), and small percentages displayed reduced Eln2 staining. By contrast, co-injecting both morpholinos at the same low doses caused a reduction in Eln2 staining in a majority of embryos and a complete lack of Eln2 staining in ∼25% of embryos (Fig. 7A-D). These data demonstrate a genetic interaction between nkx2.5 and ltbp3, suggesting that they cooperate functionally during SHF development.

Fig. 7.

nkx2.5 and ltbp3 interact genetically during zebrafish SHF development. (A-C) nkx2.5 and ltbp3 morpholinos were injected alone or together into one-cell stage embryos. Total morpholino mass remained constant between experimental groups (see Materials and methods). Injected embryos were processed at 72 hpf for MF20 (myocardium; red) and Eln2 (OFT smooth muscle; green) double immunostaining. Embryos were binned into three phenotypic classes, unaffected (A), reduced (B) or absent (C), based on Eln2 OFT signal. White brackets highlight Eln2 staining. (D) Percentages of embryos in each phenotypic class according to experimental group. The n values are reported in the graph. OFT, outflow tract; V, ventricle; Ctrl, control; MO, morpholino.

DISCUSSION

Using Cre/loxP and Kaede linage tracing, we explored the spatiotemporal characteristics of SHF progenitor specification in zebrafish embryos. We performed these studies because the recently discovered SHF-specific marker in zebrafish, ltbp3, is not detectable in the ALPM, the site of SHF specification in higher vertebrates. Based on evolutionary conservation of vertebrate cardiogenesis (Olson, 2006), we hypothesized that zebrafish SHF progenitor specification also occurs in the ALPM prior to SHF upregulation of ltbp3 in midline pharyngeal mesoderm. Alternatively, considering that zebrafish hearts have a single ventricle (Bakkers, 2011), and that ∼450 million years have passed since zebrafish and mammals diverged (Kumar and Hedges, 1998), we could not ignore the possibility that key features of SHF specification might differ in zebrafish.

Two prior reports provided initial support for ALPM specification of zebrafish SHF progenitors. First, fate mapping the zebrafish ALPM revealed mediolateral patterning of myocardial progenitors similar to that in higher vertebrates (Abu-Issa and Kirby, 2007; Schoenebeck et al., 2007), demonstrating that the overriding organization of the ALPM is conserved. Second, during the course of our study, Hami et al. (Hami et al., 2011) reported that dye tracing of ALPM cells within the zebrafish hand2+ heart forming region traced to SHF-derived myocardial and smooth muscle fates (Hami et al., 2011) consistent with the conclusion that at least some SHF progenitors are specified in the zebrafish ALPM.

Using Cre/loxP and Kaede lineage tracing of ALPM cells, we have confirmed and extended previous findings by demonstrating that: (1) as in higher vertebrates, the large majority of SHF progenitors for ventricular and OFT lineages are specified medially in the heart forming region of the ALPM; (2) the molecular signature of zebrafish ALPM SHF progenitors is gata4+ (this study), nkx2.5+ (this study) and hand2+ (Hami et al., 2011); and (3) the initiation of ltbp3 expression does not coincide temporally with SHF specification, consistent with our original conclusion that ltbp3/TGFβ signaling controls SHF proliferation (Zhou et al., 2011).

To date, bona fide SHF defects have been documented in several experimental groups of zebrafish embryos. From these studies, several factors (Tbx1, Mef2c, Isl1, Ajuba) and signaling pathways (Fgf, Bmp, Tgfβ, Hh, RA) have been implicated in zebrafish SHF development (de Pater et al., 2009; Hami et al., 2011; Hinits et al., 2012; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Witzel et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2011; Nevis et al., 2013). Many of these pathways perform indispensable functions during SHF development in higher vertebrates (Black, 2007; Rochais et al., 2009), suggesting that genetic control of SHF development is broadly conserved across vertebrates.

Despite the similarities between SHF development in higher and lower vertebrates, important differences are also apparent. First, although the mouse SHF comprises anterior and posterior subdivisions that contribute cardiac tissue to the arterial and venous poles, respectively, it remains unclear whether a bona fide posterior SHF equivalent exists in zebrafish. De Pater et al. reported that two waves of cardiomyocyte differentiation build the zebrafish heart (de Pater et al., 2009). The first wave establishes the linear heart tube and is complete by 24 hpf (de Pater et al., 2009; Lazic and Scott, 2011). The second wave, mediated by the anterior SHF equivalent, occurs exclusively at the arterial pole (de Pater et al., 2009; Hami et al., 2011; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). Two recent reports indicate that isl1+ and mef2cb+ cells reside at the venous pole of the heart tube after the first wave of differentiation is complete (Hinits et al., 2012; Witzel et al., 2012), suggesting that a posterior SHF population might exist in that location.

The ventricular endocardial potential of SHF progenitors also appears to differ between higher and lower vertebrates. In higher vertebrates, SHF progenitors give rise to a measurable part of the right ventricular endocardium (Cai et al., 2003; Milgrom-Hoffman et al., 2011; Moretti et al., 2006; Verzi et al., 2005). However, SHF cells expressing nkx2.5 in the ALPM or ltbp3 in pharyngeal mesoderm do not harbor ventricular endocardial fates (B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B., unpublished) (Zhou et al., 2011). By contrast, gata4+ ALPM cells did lineage trace to ventricular endocardium (B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B., unpublished). These findings are consistent with the ALPM fate map produced by Schoenebeck et al. (Schoenebeck et al., 2007) and previous findings demonstrating that none of the ventricular endocardium derives from late-differentiating endocardial cells (Lazic and Scott, 2011). Potentially, distal ventricular endocardial cells might arise from pre-existing ventricular endocardial cells within the heart tube that proliferate and migrate anti-parallel to the SHF derived-myocardium being accreted to the arterial pole (Lazic and Scott, 2011). Consistent with this hypothesis, the endocardium of the linear heart tube is highly proliferative (de Pater et al., 2009).

In vitro differentiation studies, or clonal assays, have been used to demonstrate multipotency of SHF progenitors in mammals (Bu et al., 2009; Moretti et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006) and avians (Hutson et al., 2010). This study and previous studies (Zhou et al., 2011) have demonstrated that zebrafish populations individually positive for gata4, nkx2.5 and ltbp3 trace to all three lineages in vivo. However, based on these results alone, and in the absence of a zebrafish clonal assay, we cannot reach a conclusion regarding the multipotency of the traced cell populations because pre-existing lineage restriction within the SHF would yield the same lineage tracing results. Indeed, a recent report demonstrated that lineage restriction of endocardial and myocardial progenitors exists within the SHF of higher vertebrates (Milgrom-Hoffman et al., 2011). If lineage diversification were to pre-exist within the SHF region of the ALPM and/or pharyngeal mesoderm, then specific SHF subpopulations might express unique genetic markers. Nonetheless, the degree of cellular heterogeneity within the zebrafish SHF remains unexplored currently.

Nkx2.5-null mice exhibit severe SHF defects manifested as reductions in the primitive right ventricle and OFT segments of the looping heart tube (Prall et al., 2007). We found that knocking down nkx2.5 with a previously validated morpholino (Targoff et al., 2008) causes similar gross phenotypes, including reductions in distal SHF-derived ventricular myocardium and OFT smooth muscle. Furthermore, we documented a reduction in SHF expression of ltbp3 and a SHF proliferation deficiency also present in ltbp3 morphants (Zhou et al., 2011). These data raise the possibility that nkx2.5 resides genetically upstream of ltbp3 to stimulate proliferation of SHF progenitors (Prall et al., 2007). Consistent with this model, we uncovered a genetic interaction between nkx2.5 and ltbp3 during SHF-mediated OFT development. The cellular function of nkx2.5 as a driver of SHF progenitor proliferation appears to be evolutionarily conserved as Nkx2.5-null mice also exhibit defects in SHF progenitor proliferation (Prall et al., 2007).

Because human NKX2.5 mutations cause congenital heart defects consistent with SHF perturbations, including tetralogy of Fallot and double outlet right ventricle (Benson et al., 1999; McElhinney et al., 2003; Nakajima, 2010), elucidating the factors and pathways upstream and downstream of nkx2.5 during vertebrate SHF development will inform clinical strategies to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with these congenital defects. Furthermore, because SHF progenitors exhibit multipotency and self-renewing capabilities (Bu et al., 2009; Laugwitz et al., 2005; Moretti et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006), they hold great potential for supporting cardiac regenerative therapies. Therefore, the genetic and environmental determinants of SHF development are deserving of continued intensive investigation using all relevant model organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Holzschuh (University of Freiburg, Germany) for providing a detailed Click-iT EdU labeling and detection protocol, W. Chen (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) for providing a plasmid with the coding sequence for ERT2CreERT2, F. Keeley (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada) for providing Eln2 anti-serum, The Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa) for providing MF20 antibody, T. J. van Ham and R. T. Peterson (Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, USA) for providing secA5-YFP expressing transgenic embryos, and the Massachusetts General Hospital Nephrology Division for access to their confocal microscopy facilities.

Footnotes

Funding

B.G.-A. was funded by an American Heart Association (AHA) Post-Doctoral Fellowship [10POST4170037], N.P.-L. was funded by the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) Training Program for Post-Doctoral Fellows [5T32HL087735], M.S.A. was funded by the Cell and Molecular Training Grant For Cardiovascular Biology [5T32HL007208], K.R.N. was funded by a National Research Service Award [5F32HL110627] from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). This work was funded by awards from the NHLBI [5R01HL111179], the March of Dimes Foundation [1-FY12-467] and the HSCI (Seed Grant and Young Investigator Award) to C.E.B.; and by NHLBI [5R01HL096816], AHA [Grant in Aid number 10GRNT4270021] and HSCI (Seed Grant) awards to C.G.B. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Author contributions

C.E.B., C.G.B. and B.G.-A. conceived the study; B.G.-A. performed the majority of experiments; N.P.-L., M.S.A., K.R.N., L.J. and P.O. performed experiments. B.G.-A., C.E.B. and C.G.B. analyzed data. K.K and K.D.P. provided the Tg(gata4:ERCreER) transgenic strain. C.G.B., C.E.B. and B.G.-A. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.088351/-/DC1

References

- Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. (2004). Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Issa R., Kirby M. L. (2007). Heart field: from mesoderm to heart tube. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 45–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando R., Hama H., Yamamoto-Hino M., Mizuno H., Miyawaki A. (2002). An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12651–12656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajolle F., Zaffran S., Kelly R. G., Hadchouel J., Bonnet D., Brown N. A., Buckingham M. E. (2006). Rotation of the myocardial wall of the outflow tract is implicated in the normal positioning of the great arteries. Circ. Res. 98, 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkers J. (2011). Zebrafish as a model to study cardiac development and human cardiac disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 91, 279–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D. W., Silberbach G. M., Kavanaugh-McHugh A., Cottrill C., Zhang Y., Riggs S., Smalls O., Johnson M. C., Watson M. S., Seidman J. G., et al. (1999). Mutations in the cardiac transcription factor NKX2.5 affect diverse cardiac developmental pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 1567–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B. L. (2007). Transcriptional pathways in second heart field development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 67–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau B. G. (2008). The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature 451, 943–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu L., Jiang X., Martin-Puig S., Caron L., Zhu S., Shao Y., Roberts D. J., Huang P. L., Domian I. J., Chien K. R. (2009). Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature 460, 113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C. L., Liang X., Shi Y., Chu P. H., Pfaff S. L., Chen J., Evans S. (2003). Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev. Cell 5, 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. N., Fishman M. C. (1996). Zebrafish tinman homolog demarcates the heart field and initiates myocardial differentiation. Development 122, 3809–3816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pater E., Clijsters L., Marques S. R., Lin Y. F., Garavito-Aguilar Z. V., Yelon D., Bakkers J. (2009). Distinct phases of cardiomyocyte differentiation regulate growth of the zebrafish heart. Development 136, 1633–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer L. A., Kirby M. L. (2009). The role of secondary heart field in cardiac development. Dev. Biol. 336, 137–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. A., Kirk E. P., Yeoh T., Chandar S., McKenzie F., Taylor P., Grossfeld P., Fatkin D., Jones O., Hayes P., et al. (2003). Cardiac homeobox gene NKX2-5 mutations and congenital heart disease: associations with atrial septal defect and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 2072–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. A. (2010). Franklin H. Epstein Lecture. Cardiac development and implications for heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1638–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Stachura D. L., White R. M., Gutierrez A., Zhang L., Sanda T., Jette C. A., Testa J. R., Neuberg D. S., Langenau D. M., et al. (2010). T-lymphoblastic lymphoma cells express high levels of BCL2, S1P1, and ICAM1, leading to a blockade of tumor cell intravasation. Cancer Cell 18, 353–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes A. C., Stadt H. A., Shepherd I. T., Kirby M. L. (2006). Solving an enigma: arterial pole development in the zebrafish heart. Dev. Biol. 290, 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes A. C., Durán A. C., Sans-Coma V., Hami D., Santoro M. M., Torres M. (2010). Phylogeny informs ontogeny: a proposed common theme in the arterial pole of the vertebrate heart. Evol. Dev. 12, 552–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hami D., Grimes A. C., Tsai H. J., Kirby M. L. (2011). Zebrafish cardiac development requires a conserved secondary heart field. Development 138, 2389–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans S., Kaslin J., Freudenreich D., Brand M. (2009). Temporally-controlled site-specific recombination in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 4, e4640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heicklen-Klein A., Evans T. (2004). T-box binding sites are required for activity of a cardiac GATA-4 enhancer. Dev. Biol. 267, 490–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinits Y., Pan L., Walker C., Dowd J., Moens C. B., Hughes S. M. (2012). Zebrafish Mef2ca and Mef2cb are essential for both first and second heart field cardiomyocyte differentiation. Dev. Biol. 369, 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson M. R., Zeng X. L., Kim A. J., Antoon E., Harward S., Kirby M. L. (2010). Arterial pole progenitors interpret opposing FGF/BMP signals to proliferate or differentiate. Development 137, 3001–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilagan R., Abu-Issa R., Brown D., Yang Y. P., Jiao K., Schwartz R. J., Klingensmith J., Meyers E. N. (2006). Fgf8 is required for anterior heart field development. Development 133, 2435–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. G. (2012). The second heart field. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 100, 33–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. G., Brown N. A., Buckingham M. E. (2001). The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm. Dev. Cell 1, 435–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K., Holdway J. E., Werdich A. A., Anderson R. M., Fang Y., Egnaczyk G. F., Evans T., Macrae C. A., Stainier D. Y., Poss K. D. (2010). Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature 464, 601–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Hedges S. B. (1998). A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature 392, 917–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz K. L., Moretti A., Lam J., Gruber P., Chen Y., Woodard S., Lin L. Z., Cai C. L., Lu M. M., Reth M., et al. (2005). Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature 433, 647–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazic S., Scott I. C. (2011). Mef2cb regulates late myocardial cell addition from a second heart field-like population of progenitors in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 354, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q., Zhou B., Pu W. T. (2008). Reassessment of Isl1 and Nkx2-5 cardiac fate maps using a Gata4-based reporter of Cre activity. Dev. Biol. 323, 98–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mably J. D., Mohideen M. A., Burns C. G., Chen J. N., Fishman M. C. (2003). heart of glass regulates the concentric growth of the heart in zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 13, 2138–2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler G. J., Butcher J. T. (2011). Cardiac developmental toxicity. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 93, 291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler J., Filippi A., Driever W. (2010). DeltaA/DeltaD regulate multiple and temporally distinct phases of notch signaling during dopaminergic neurogenesis in zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 30, 16621–16635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., Cepko C. L. (2007). Controlled expression of transgenes introduced by in vivo electroporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1027–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhinney D. B., Geiger E., Blinder J., Benson D. W., Goldmuntz E. (2003). NKX2.5 mutations in patients with congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42, 1650–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao M., Bruce A. E., Bhanji T., Davis E. C., Keeley F. W. (2007). Differential expression of two tropoelastin genes in zebrafish. Matrix Biol. 26, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom-Hoffman M., Harrelson Z., Ferrara N., Zelzer E., Evans S. M., Tzahor E. (2011). The heart endocardium is derived from vascular endothelial progenitors. Development 138, 4777–4787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A., Caron L., Nakano A., Lam J. T., Bernshausen A., Chen Y., Qyang Y., Bu L., Sasaki M., Martin-Puig S., et al. (2006). Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell 127, 1151–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann C., Kaufman C. K., Li P., Pugach E. K., Tamplin O. J., Zon L. I. (2011). Ubiquitous transgene expression and Cre-based recombination driven by the ubiquitin promoter in zebrafish. Development 138, 169–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y. (2010). Second lineage of heart forming region provides new understanding of conotruncal heart defects. Congenit. Anom. (Kyoto) 50, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevis K., Obregon P., Walsh C., Guner-Ataman B., Burns C. G., Burns C. E. (2013). Tbx1 is required for second heart field proliferation in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Olson E. N. (2006). Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart. Science 313, 1922–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prall O. W., Menon M. K., Solloway M. J., Watanabe Y., Zaffran S., Bajolle F., Biben C., McBride J. J., Robertson B. R., Chaulet H., et al. (2007). An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell 128, 947–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochais F., Mesbah K., Kelly R. G. (2009). Signaling pathways controlling second heart field development. Circ. Res. 104, 933–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger V. L., Go A. S., Lloyd-Jones D. M., Benjamin E. J., Berry J. D., Borden W. B., Bravata D. M., Dai S., Ford E. S., Fox C. S., et al. (2012). Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 125, e2–e220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenebeck J. J., Keegan B. R., Yelon D. (2007). Vessel and blood specification override cardiac potential in anterior mesoderm. Dev. Cell 13, 254–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott J. J., Benson D. W., Basson C. T., Pease W., Silberbach G. M., Moak J. P., Maron B. J., Seidman C. E., Seidman J. G. (1998). Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5. Science 281, 108–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava D., Olson E. N. (2000). A genetic blueprint for cardiac development. Nature 407, 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley E. G., Biben C., Elefanty A., Barnett L., Koentgen F., Robb L., Harvey R. P. (2002). Efficient Cre-mediated deletion in cardiac progenitor cells conferred by a 3’UTR-ires-Cre allele of the homeobox gene Nkx2-5. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46, 431–439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suster M. L., Sumiyama K., Kawakami K. (2009). Transposon-mediated BAC transgenesis in zebrafish and mice. BMC Genomics 10, 477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targoff K. L., Schell T., Yelon D. (2008). Nkx genes regulate heart tube extension and exert differential effects on ventricular and atrial cell number. Dev. Biol. 322, 314–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ham T. J., Mapes J., Kokel D., Peterson R. T. (2010). Live imaging of apoptotic cells in zebrafish. FASEB J. 24, 4336–4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzi M. P., McCulley D. J., De Val S., Dodou E., Black B. L. (2005). The right ventricle, outflow tract, and ventricular septum comprise a restricted expression domain within the secondary/anterior heart field. Dev. Biol. 287, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent S. D., Buckingham M. E. (2010). How to make a heart: the origin and regulation of cardiac progenitor cells. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 90, 1–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Both I., Silvestri C., Erdemir T., Lickert H., Walls J. R., Henkelman R. M., Rossant J., Harvey R. P., Attisano L., Wrana J. L. (2004). Foxh1 is essential for development of the anterior heart field. Dev. Cell 7, 331–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C., Stadt H., Hutson M., Kirby M. L. (2005). Ablation of the secondary heart field leads to tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia. Dev. Biol. 284, 72–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2000). The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; [Google Scholar]

- Witzel H. R., Jungblut B., Choe C. P., Crump J. G., Braun T., Dobreva G. (2012). The LIM protein Ajuba restricts the second heart field progenitor pool by regulating Isl1 activity. Dev. Cell 23, 58–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. M., Fujiwara Y., Cibulsky S. M., Clapham D. E., Lien C. L., Schultheiss T. M., Orkin S. H. (2006). Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell 127, 1137–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D., Horne S. A., Stainier D. Y. (1999). Restricted expression of cardiac myosin genes reveals regulated aspects of heart tube assembly in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 214, 23–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Cashman T. J., Nevis K. R., Obregon P., Carney S. A., Liu Y., Gu A., Mosimann C., Sondalle S., Peterson R. E., et al. (2011). Latent TGF-β binding protein 3 identifies a second heart field in zebrafish. Nature 474, 645–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.