Abstract

Objective

To present the pregnancy results and interim birth results of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing routine iron prophylaxis with screening and treatment for anaemia during pregnancy in a setting of endemic malaria and HIV.

Design

A pragmatic randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Two health centres (1° de Maio and Machava) in Maputo, Mozambique, a setting of endemic malaria and high prevalence of HIV.

Participants

Pregnant women (≥18-year-olds; non-high-risk pregnancy, n=4326) attending prenatal care consultation at the two health centres were recruited to the trial.

Interventions

The women were randomly allocated to either Routine iron (n=2184; 60 mg ferrous sulfate plus 400 μg of folic acid daily throughout pregnancy) or Selective iron (n=2142; screening and treatment for anaemia and daily intake of 1 mg of folic acid).

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were preterm delivery (delivery <37 weeks of gestation) and low birth weight (<2500 g). The secondary outcomes were symptoms suggestive of malaria and self-reported malaria during pregnancy; birth length; caesarean section; maternal and child health status after delivery.

Results

The number of follow-up visits was similar in the two groups. Between the first and fifth visits, the two groups were similar regarding the occurrence of fever, headache, cold/chills, nausea/vomiting and body aches. There was a suggestion of increased incidence of self-reported malaria during pregnancy (OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.98 to1.92) in the Routine iron group. Birth data were available for 1109 (51%) in the Routine iron group and for 1149 (54%) in the Selective iron group. The birth outcomes were relatively similar in the two groups. However, there was a suggestion (statistically non-significant) of poorer outcomes in the Routine iron group with regard to long hospital stay after birth (relative risk (RR) 1.43, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.26; risk difference (RD) 0.02, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.03) and unavailability of delivery data (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.13; RD 0.03, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.07).

Conclusions

These interim results suggest that routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy did not confer advantage over screening and treatment for anaemia regarding maternal and child health. Complete data on birth outcomes are being collected for firmer conclusions.

Trial registration

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00488579 (June 2007). The first women were randomised to the trial proper April 2007–March 2008. The pilot was November 2006–March 2008. The 3-month lag was due to technical difficulties in completing trial registration.

Keywords: Preventive Medicine, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

The benefits of iron prophylaxis during pregnancy on maternal and child health (MCH) in developing country settings with endemic malaria and high prevalence of HIV is unclear.

Iron has been linked to increased risk of infections.

Among children less than 3 years, there are indications of harm of universal iron prophylaxis.

Key messages

Routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy did not suggest better maternal and child health (MCH) outcomes than screening and treatment for anaemia in a setting of endemic malaria and HIV.

Strengths and limitations of this study

So far, this represents the largest trial investigating the benefits of prophylactic iron during pregnancy on MCH in malaria-endemic settings.

The compliance of the study nurses with the trial protocol and that of the women with regard to uptake of the iron and folic acid tablets was good, as was the follow-up during pregnancy.

The collection of delivery data was challenging, resulting in up to an estimated 40% of missing birth data, which are now been traced using various methods.

Introduction

Despite the widespread recommendation of routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy, its benefits and risks for the mother and child, beyond the reduction of the risk of anaemia, remain unclear, particularly in low-income settings. Reviews of randomised controlled trials (RTCs) performed for the Cochrane Collaboration and the WHO have failed to conclude on the effects of routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy on pregnancy and birth outcomes.1 2 There is some evidence that high haemoglobin concentration in late pregnancy may be associated with adverse effects on pregnancy.3 4 Based on the evidence from non-pregnant populations, it has been suggested that iron may advance the rate of infections.5–7 The host requires iron for biochemical functioning, but iron may as well promote the replication of infectious agents.6 For developing country settings which are still plagued by infectious diseases, such as malaria and HIV, the possible association between iron and infections raises serious public health concerns.8 9

Previous trials conducted in malarial developing country settings that have evaluated the effects of iron supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and child outcomes have been hampered by small samples, large dropouts and several outcome-related exclusions.10–14 The findings from the trials were conflicting on the role of prophylactic iron supplementation on birth weight, prematurity, perinatal mortality, incidence of malaria and other pregnancy and birth outcomes. Consequently, the evidence they provide is insufficient in addressing the question of the advantages and disadvantages of prenatal prophylactic iron. The results of studies from non-malarial areas,15–21 although of better quality, may not be relevant due to different settings.15–21 Although the results were also conflicting in a number of outcomes, the main findings included slightly longer birth length, longer gestational age and reduced risk of preterm delivery, intrapartum haemorrhage, low birth weight and infant and child mortality in the iron–folic acid group.22

This limited evidence and the importance of iron prophylaxis in prenatal programmes call for further investigation on the benefits of prenatal iron supplementation in areas of endemic malaria and with a high prevalence of HIV. Using a pragmatic RCT, we investigated the effects of routine iron prophylaxis throughout pregnancy compared with screening and treatment for anaemia on maternal and child health (MCH) in Maputo, Mozambique. The present paper presents the pregnancy results and interim birth results. About 40% of births were missed by the original data collection method;22 the missing birth data are currently being retrieved with various complementary methods. The completed birth results will be presented later.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The details of the PROFEG trial have been described elsewhere22 and only the main features are given here. The trial was a pragmatic RCT to compare two iron administration policies (routine iron prophylaxis vs screening and treatment for anaemia during pregnancy) on MCH in Maputo, Mozambique. The trial was carried out in two health centres, 1o de Maio in Maputo City, the capital (November 2006—October 2008), and Machava 2 in Maputo Province (June 2007—October 2008), Mozambique. The completion of collection of birth data continued until 2012. The health centre of Machava 2 in Maputo province is close to Maputo city. The population is urban and semiurban, and malaria is endemic in both areas. A seasonal increase of malaria is usually observed towards the end of the rainy season (February–April).23

In the study area, all woman were eligible to attend prenatal care. The usual care recommendations at the time of the trial included daily prophylactic iron–folate supplementation (60 mg+400 μg) throughout pregnancy; one dose of mebendazol 500 mg for intestinal parasite; three doses of sulfadoxine pyrimethamine for malaria prophylaxis (started around 20 weeks gestation, or when quickening occurs or when the fetal heart is heard); haemoglobin measurement (Lovibond is routinely used) and syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit and three doses of tetanus vaccine (at the fifth and seventh months and at delivery). If malaria was suspected during prenatal consultations, it was diagnosed by laboratory tests and clinical signs. In most health centres, including our study centres, HIV testing was offered.22 Antiretroviral (ARV) drugs were provided by various international organisations, but we do not have information of how many women received treatment during pregnancy. The recommendation was to give ARV (Nevirapine) at delivery to prevent mother–child transmission.

Recruitment of study participants

Pregnant women attending their first prenatal visit were the target group. During the routine early morning health education sessions, all women who came for their first prenatal visit were given general information about the study. Recruitment into the study occurred during individual consultations and was carried out by study nurses who were employed and trained by the project. In the 1° de Maio health centre, the women visited the study nurses after their routine prenatal care consultations with the MCH nurses. In Machava, the study nurse and the routine MCH nurse saw the women in the same room. The study nurses checked for the women's eligibility to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were: women with high obstetric risk and those aged less than 18 years. If eligible, the nurses asked the women to join the study. Oral and written informed consent was obtained. Three types of women were missed from the study: women whom MCH nurses sent back home because of too early pregnancy, women who did not go to the study nurse and women who refused the study.

Randomisation

The women were randomised into either the Routine iron group (ie, routine iron prophylaxis from the first to the last prenatal visit) or the Selective iron group (ie, regular screening for haemoglobin level and treatment for anaemia). Researcher (OA) used the STATA statistical software (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) to generate sequential random numbers separately for the two centres, and the women were assigned to either of the groups with a probability of 50%. The codes for the groups were put into sealed and numbered opaque envelopes; the number was the woman’s study number and was repeated in the documents in the envelope. The envelope contained a study identification card (yellow for the Routine iron group and pink for the Selective iron group, 10×20 cm) and the informed consent form.

Sample size

We did not have up-to-date reliable baseline data of pregnant women's and newborns’ health in Maputo or of the effects of iron on pregnancy and birth outcomes. Thus, we used different estimates of the baseline values for preterm delivery, low birth weight, clinical malaria and perinatal mortality to calculate the sample size, with power (85% and 90%), significance level of 5% and the size of the difference to be detected (20% and 30%). Based on these calculations and the expected feasibility, we decided on a sample size of 2000 women in each group to be enough to measure clinically meaningful effects. The STATA statistical software was used to estimate the sample size. A table showing the various baseline assumptions used for power calculation and in estimating the sample size for the study is included as online supplementary appendix 1.

Interventions

On each prenatal visit, women in the Routine iron group received 30 tablets (supply of 1 month) of 60 mg ferrous sulfate plus 400 μg of folic acid per day combined in one tablet. In the Selective iron group, women's haemoglobin levels were measured at each visit by the study nurses using a rapid haemoglobin measure, HemoCue Hb 201+, (Hemocue AB, Ängelholm, Sweden). If the haemoglobin was 9 g/dl or more, they received 30 tablets of 1 mg of folic acid per day. If their haemoglobin was below the cut-off of <9 g/dl haemoglobin, they received a monthly double dose of iron (60 mg+60 mg) for the treatment of anaemia. Folic acid 1 mg tablets were used because at the time of the trial pure folic acid was not licensed in Mozambique in 400 μg tablets. The tablets were given in a plastic bag having the drug’s name and dosage on it.

Data collection and follow-up

Data were collected on standard study data forms by three methods: (1) study nurses abstracted prenatal data from mothers’ maternity cards, (2) study nurses asked women additional questions at the time of the prenatal visits and (3) study nurses or researchers collected birth data afterwards from hospital birth records. Delivery nurses were informed of the study and asked to put the delivery cards into a separate study box. The study women were to be identified by the colour of the identification card stapled to their maternity card. However, this did not succeed very well. By excluding estimated late miscarriages (5%), early stillbirths (3%) and home births (10%), we should have received delivery data for 3547 women (82%) of the 4326 women who participated in the trial. We received birth data for only 2258 (64% of the estimated 3547) women.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were preterm delivery (delivery <37 weeks of gestation and low birth weight (<2500 g); data on weight came from the birth records; for gestation weeks, various routine data sources were used (see below). Originally, we had malaria activation as a primary outcome, but the pilot showed that it was not feasible. Secondary outcomes were perinatal mortality (as available from our data collection forms; unlikely to cover early stillbirths or neonatal deaths occurring at home); complications during pregnancy and labour; symptoms suggestive of malaria (fever, headache, cold/chills, nausea/vomiting and body aches) and self-reported malaria during pregnancy (the woman was asked for diagnosed malaria since her last visit).

Gestational weeks

In the prenatal visits, routine MCH nurses determined gestational weeks in various ways, even though all ways were not systematically noted down. In the first prenatal visits, the date of the last menstrual period, uterine fundal height, assumed date of delivery and length of gestation (best estimate) were noted. The study nurses abstracted all this information and the best estimate was used in this paper. In birth records, the last menstrual period, date of fertilisation, assumed date of fertilisation and length of gestation were to be given by the delivery nurses. However, these data were very poorly filled and only 681 (30%) of the women with delivery data had their gestational weeks recorded at birth. Thus, the gestational weeks for women without that information were estimated from dates using the following algorithm: gestational weeks at first visit in days+days between the first visit and delivery; the days were then transformed into weeks. For some women (n=196), the date of delivery was not available. In these cases, the date of discharge from the hospital after delivery (minus the length of stay at the hospital; n=22) or the date of admission to the hospital (n=60 women who did not have the date of discharge) was used.

Adherence

The women were instructed and encouraged at each visit to take the tablets they were given. Women allocated to the Routine iron group could refuse to take the iron tablets; in that case, they were classified as non-compliant with the intervention. Women who belonged in the Selective iron group and who wanted iron (even if their haemoglobin level was not below the cut-off level) were given iron; they were classified as non-compliant with the intervention. The following questions were asked on each visit: ‘Was hemoglobin measured?’; ‘Was iron/folic acid given to the woman?’; ‘Number of iron/folic acid tablets given?’; ‘Did the woman take the tablets during the past week?’ At each subsequent visit, almost all of the Selective iron women (98%) were measured for haemoglobin using the recommended HemoCue method and the same proportion of women in the Routine iron group were given iron tablets at each subsequent visit.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Twin pregnancies (n=48 pairs) were included in the analysis because their numbers were similar in the two groups and their exclusion did not alter the results. For pregnancy outcomes, all women (n=4326) were included, whereas for birth outcomes, women with birth data (n=2258) were included. Differences in health indicators (fever, headache, cold/chills, nausea/vomiting, body aches, malaria) between the two iron groups at each subsequent visit (up to the fifth visit) during pregnancy were analysed by using binomial generalised estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation structure. GEE takes into account the within person correlation in the setting of repeated measures.

Differences in continuously distributed birth outcomes (birth weight, duration of gestation, length of hospital stay) were analysed by using the two sample Student t tests. Categorical outcomes were analysed by using Pearson'sχ2 test or Fisher's exact test (in the case of cells with less than five cases). To estimate the risk ratios of the effect of iron, the binary birth outcomes (low birth weight (<2500 g), preterm birth (<37 weeks), caesarean section delivery, child and maternal ill-health or death at birth, negative fetal heart beat, delivery in a reference health centre, long hospital stay after birth (≥ 2 days) and unavailability of delivery data) were analysed by generalised linear models. The result estimates are presented with 95% CI. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. STATA V.11 statistical software was used for the analyses.

Results

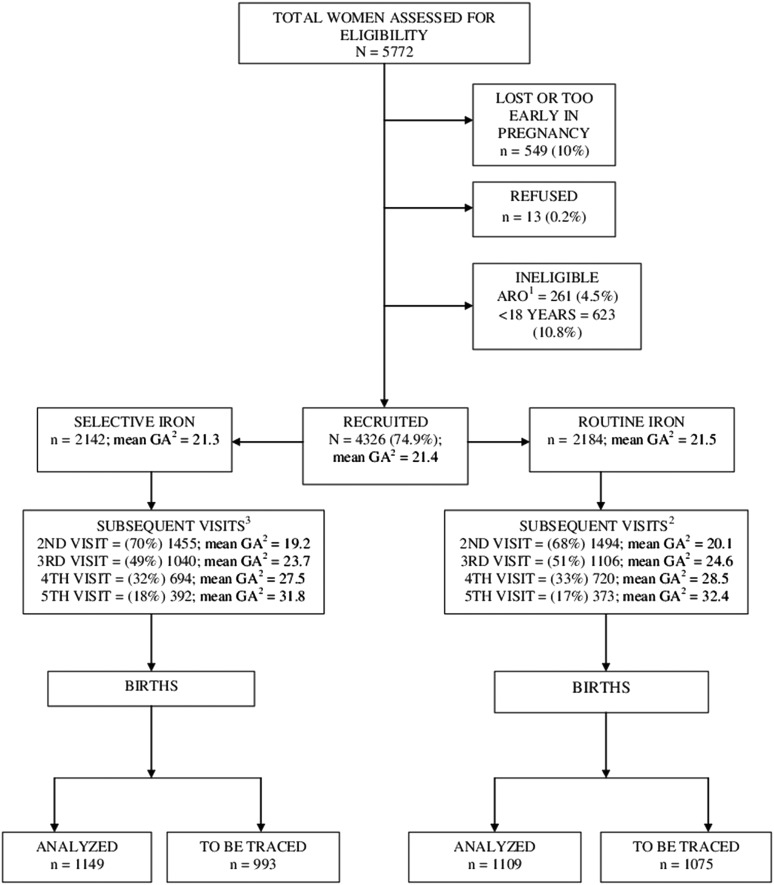

Of the 4326 women recruited to the trial, 2184 were randomly allocated to the Routine iron group and 2142 to the Selective iron group (figure 1). The total number of prenatal visits varied, but the maximum number of visits was seven. The number of follow-up visits was similar in the two groups (figure 1). About 40% of the delivery data were missed when using the original data collection method and the interim birth data were available for 1109 (51%) in the Routine iron group and for 1149 (54% of women) in the Selective iron group.

Figure 1.

PROFEG Trial flow diagram. 1ARO, high-risk pregnancy; 2GA, gestational age in weeks; 3After recruitment, % were calculated from recruited, n=4326.

Table 1 compares maternal background characteristics between groups by the availability of birth data. Mean haemoglobin for the Selective group was similar between those with and without delivery data. The occurrence of symptoms suggestive of malaria (fever, headache, cold/chills, nausea/vomiting and body aches) and self-reported malaria during the current pregnancy prior to the first prenatal visit was similar between the Routine and Selective iron groups. The women in the two groups with and without birth data were comparable.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women at recruitment by availability of delivery data and group allocation, proportions % (numbers)

| Delivery data (n=2258) |

No delivery data (n=2068) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Selective iron (1149) % (n) | Routine iron (1109) % (n) | Selective iron (993) % (n) | Routine iron (1075) % (n) |

| Maternal age, mean (SD) years | 24.6 (5.4) | 24.7 (5.3) | 25.0 (5.6) | 24.6 (5.6) |

| Maternal age (years) (categorised) | ||||

| <20 | 17.5 (201) | 16.5 (183) | 15.7 (156) | 19.3 (207) |

| 20–24 | 41.1 (472) | 39.9 (443) | 39.0 (387) | 37.1 (399) |

| 25–29 | 23.1 (265) | 23.3 (258) | 23.9 (237) | 23.4 (252) |

| 30–34 | 11.3 (130) | 13.8 (153) | 12.9 (128) | 13.3 (143) |

| ≥35 | 6.3 (72) | 5.6 (62) | 7.4 (74) | 6.5 (70) |

| Missing | 0.8 (9) | 0.9 (10) | 1.1 (11) | 0.4 (4) |

| Haemoglobin by HemoCue (g/dl), mean (SD) | 9.6 (1.7) | 9.6 (1.7) | ||

| Haemoglobin by HemoCue (g/dl), n (%) | ||||

| <7.0 | 6.9 (79) | 6.2 (62) | ||

| 7.0–8.90 | 24.6 (283) | 25.4 (252) | ||

| 9.0–9.90 | 23.5 (270) | 24.4 (242) | ||

| 10.0–10.90 | 21.9 (252) | 21.1 (210) | ||

| 11.0–11.90 | 14.1 (162) | 13.7 (136) | ||

| ≥ 12.0 | 7.9 (91) | 8.4 (83) | ||

| Not measured | 1.0 (12) | 0.8 (8) | ||

| Previous abortions | ||||

| No | 87.6 (1007) | 86.8 (963) | 86.0 (854) | 85.4 (918) |

| Yes | 12.1 (139) | 12.8 (142) | 13.6 (135) | 14.5 (156) |

| Missing | 0.3 (3) | 0.4 (4) | 0.4 (4) | 0.1 (1) |

| Gestational age, mean (SD) weeks | 21.6 (5.9) | 21.7 (5.6) | 21.0 (5.9) | 21.3 (5.8) |

| Gestational age (categorised) | ||||

| <16 | 19.2 (221) | 16.4 (182) | 21.5 (213) | 20.1 (216) |

| 17–20 | 21.8 (250) | 24.2 (268) | 22.5 (223) | 21.7 (233) |

| 21–26 | 34.3 (394) | 32.6 (361) | 31.3 (311) | 33.7 (362) |

| >27 | 19.7 (226) | 19.7 (219) | 17.5 (174) | 18.2 (196) |

| No information | 58 (5.0) | 7.1 (79) | 7.3 (72) | 6.3 (68) |

| Previous stillbirths | ||||

| No | 91.5 (1052) | 92.3 (1024) | 91.6 (910) | 91.0 (978) |

| Yes | 8.2 (94) | 7.2 (80) | 7.9 (78) | 8.9 (96) |

| Missing | 0.3 (3) | 0.5 (5) | 0.5 (5) | 0.1 (1) |

| Previous deliveries | ||||

| None | 29.7 (341) | 30.3 (336) | 29.2 (290) | 33.8 (363) |

| One | 31.9 (367) | 31.7 (352) | 30.6 (304) | 28.5 (306) |

| Two | 19.2 (221) | 17.8 (197) | 17.9 (178) | 18.6 (200) |

| Three or more | 18.8 (216) | 19.8 (220) | 22.0 (218) | 19.0 (205) |

| Missing | 0.4 (4) | 0.4 (4) | 0.3 (3) | 0.1 (1) |

| HIV status | ||||

| Negative | 81.2 (934) | 81.8 (907) | 76.7 (762) | 79.0 (849) |

| Positive | 18.8 (215) | 18.2 (202) | 23.3 (231) | 21.0 (226) |

| Twin pregnancy | ||||

| No | 98.7 (1134) | 98.6 (1093) | 99.2 (985) | 99.2 (1066) |

| Yes | 1.3 (15) | 1.4 (16) | 0.8 (8) | 0.8 (9) |

| Symptoms during current pregnancy before first prenatal visit | ||||

| Fever | ||||

| Yes | 22.9 (264) | 24.4 (271) | 28.8 (286) | 23.8 (256) |

| Headache | ||||

| Yes | 41.5 (477) | 43.5 (482) | 44.3 (440) | 43.0 (462) |

| Cold/chills | ||||

| Yes | 18.0 (207) | 18.4 (204) | 20.6 (205) | 18.8 (202) |

| Vomit/nausea | ||||

| Yes | 27.5 (316) | 26.9 (298) | 29.8 (296) | 28.6 (307) |

| Body aches | ||||

| Yes | 21.8 (251) | 21.3 (237) | 23.8 (236) | 23.3 (251) |

| Self-reported malaria | ||||

| Yes | 5.7 (66) | 6.0 (67) | 5.9 (59) | 6.3 (68) |

| Had malaria test | ||||

| Yes | 7.0 (80) | 7.1 (79) | 8.0 (79) | 7.9 (85) |

Between the first and fifth visits, the two groups were similar regarding the occurrence of fever, headache, cold/chills, nausea/vomiting and body aches (table 2). There was a suggestion of increased incidence of self-reported malaria during pregnancy (OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.92) in the Routine iron group (table 2). Table 2 presents the data for the second and third follow-up visits, but this was the case also in subsequent visits (data not shown).

Table 2.

Proportions (%) of women (numbers) with outcomes suggesting malaria during pregnancy, and OR and 95% CIs for group effect, n=4326

| Outcomes | Second visit* % (n) |

Third visit† % (n) |

Between the first and fifth visit‡ OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective iron n=1455 | Routine iron n=1494 | Selective iron n=1040 | Routine iron n=1106 | Selective iron | Routine iron | p Value | |

| Fever | 11.5 (168) | 10.0 (150) | 11.3 (117) | 12.1 (134) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) | 0.523 |

| Headache | 24.9 (363) | 24.3 (363) | 24.9 (259) | 25.1 (278) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.10) | 0.738 |

| Cold/chills | 8.2 (120) | 7.0 (104) | 6.7 (70) | 7.8 (86) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.11) | 0.361 |

| Vomit/nausea | 9.1 (133) | 10.2 (153) | 8.5 (88) | 9.6 (109) | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.31) | 0.323 |

| Body aches | 10.1 (147) | 9.2 (138) | 10.9 (113) | 9.8 (108) | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.06) | 0.180 |

| Self-reported malaria | 2.4 (35) | 3.0 (45) | 1.5 (16) | 2.2 (24) | 1.00 | 1.37 (0.98 to 1.92) | 0.068 |

*Between the first and second visit.

†Between the second and third visit.

‡The effect estimates calculated by binomial generalised estimating equations (with exchangeable correlation structure) to account for the repeated measures of the outcomes.

Table 3 presents the distribution of birth data by intervention group and table 4 gives the estimates of the effect sizes on the birth outcomes. The birth outcomes were similar in the two groups. However, there was a suggestion (statistically non-significant) that the Routine iron group had worse outcomes in regard to babies with a negative heartbeat at admission and longer mother's hospital stay after birth (table 3). The effect of iron on the primary outcomes was similar in the two groups. The groups were also relatively similar concerning most other outcomes. However, there was a suggestion of more babies with negative fetal heartbeat at admission, longer mother's hospital stay after birth and unavailability of delivery data in the Routine iron group (table 4). By excluding births by caesarean section, the estimates for longer mother's hospital stay remained the same (data not shown).

Table 3.

Birth outcomes by group allocation, percentages, % (numbers) of women or babies or means (SD)

| Outcomes | Selective iron (n=1149) | Routine iron (n=1109) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight, mean (SD) grams | 2996.3 (508.4) | 2989.4 (514.9) | 0.752 |

| Birth weight (g), % (n) | 0.443 | ||

| <2500 | 11.8 (136) | 12.8 (142) | |

| 2500–2999 | 30.6 (351) | 31.1 (345) | |

| 3000–3499 | 40.5 (465) | 37.8 (419) | |

| 3500–3999 | 12.7 (146) | 13.8 (153) | |

| ≥4000 | 3.0 (34) | 2.1 (23) | |

| No information | 1.5 (17) | 2.4 (27) | |

| Duration of gestation, mean (SD) weeks | 38.3 (4.2) | 38.4 (4.0) | 0.689 |

| Duration of gestation, % (n) | 0.056 | ||

| <37 weeks | 28.8 (331) | 27.0 (299) | |

| ≥37 weeks | 67.2 (772) | 66.9 (742) | |

| No information | 4.0 (46) | 6.1 (68) | |

| Mode of delivery, % (n) | 0.235 | ||

| Normal | 87.6 (1007) | 89.4 (991) | |

| Caesarean section | 1.3 (15) | 2.0 (22) | |

| No information | 11.1 (127) | 8.7 (96) | |

| Child health status at birth, % (n) | 0.685 | ||

| Well | 94.0 (1080) | 92.1 (1022) | |

| Ill | 0.7 (8) | 1.0 (11) | |

| Dead | 1.8 (21) | 2.0 (22) | |

| No information | 3.5 (40) | 5.0 (55) | |

| Still birth, % (n) | 0.558 | ||

| No | 81.2 (933) | 79.7 (884) | |

| Yes | 2.5 (29) | 2.9 (32) | |

| No information | 16.3 (187) | 17.4 (193) | |

| Fetal heart beat at admission, % (n) | 0.085 | ||

| Negative | 1.6 (18) | 2.6 (29) | |

| Positive | 85.6 (984) | 85.2 (945) | |

| No information | 12.8 (147) | 12.2 (135) | |

| Mother's health status at birth, % (n) | 0.895 | ||

| Well | 95.6 (1098) | 94.9 (1052) | |

| Ill | 0.4 (4) | 0.4 (4) | |

| Dead | 0.1 (1) | 0.2 (2) | |

| No information | 4.0 (46) | 4.6 (51) | |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) days | 1.33 (1.21) | 1.63 (1.30) | 0.075 |

| Length of hospital stay after birth, % (n) | 0.103 | ||

| ≤1 day | 65.1 (748) | 60.7 (673) | |

| 2 days | 23.5 (270) | 24.2 (268) | |

| ≥3 days | 4.0 (46) | 5.6 (62) | |

| No information | 7.4 (85) | 9.6 (106) | |

| Place of delivery, % (n) | 0.652 | ||

| 1o de Maio (health centre) | 44.4 (510) | 42.6 (472) | |

| Machava (health centre) | 35.1 (403) | 38.2 (424) | |

| Jose Macamo (hospital) | 3.7 (43) | 3.6 (40) | |

| Mavalane (hospital) | 14.3 (164) | 12.8 (142) | |

| Central hospital | 0.3 (3) | 0.3 (3) | |

| At home | 1.1 (13) | 1.3 (14) | |

| On the way to hospital | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (2) | |

| No information | 1.1 (13) | 1.1 (12) |

*Based on t test for continuous outcomes, Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical outcomes. Subjects with no information were not included in the tests.

Table 4.

Numbers, proportions (%) and risk ratios (RR, 95% CIs of birth outcomes by iron groups

| Outcomes | Selective iron n | Routine iron n | Selective iron (%) | Routine iron (%) | Selective iron | Routine iron RR (95% CI)† | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary health outcomes | |||||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 136 | 142 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.36) | 0.431 |

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) | 331 | 299 | 28.8 | 27.0 | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.84 to1.09) | 0.185 |

| Secondary health outcomes | |||||||

| Caesarean section delivery | 15 | 22 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.48 (0.77 to 2.84) | 0.238 |

| Negative fetal heart beat at admission | 18 | 29 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.00 | 1.66 (0.93 to 2.96) | 0.089 |

| Child ill or dead at birth | 29 | 33 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.73 to 1.96) | 0.473 |

| Mother ill or dead at birth | 5 | 6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.00 | 1.25 (0.38 to 4.09) | 0.711 |

| Other outcomes | |||||||

| Delivery in reference centre* | 210 | 185 | 18.3 | 16.7 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) | 0.316 |

| Long hospital stay after delivery (≥ 3 days) | 46 | 62 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 1.00 | 1.43 (0.97 to 1.26) | 0.059 |

| No delivery data | 993 | 1075 | 46.4 | 49.2 | 1.00 | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.13) | 0.060 |

*Jose Macamo or Mavalane or Central Hospital.

†The estimates were not adjusted for any baseline characteristic because the two groups did not differ from each other at baseline.

Discussion

The results from this trial indicate that routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy was not advantageous over the policy of screening and treatment for anaemia with regard to pregnancy and birth outcomes. If anything, screening and treatment for anaemia appeared to be better. Among all the trial women, there was a suggestion of an increased risk of self-reported malaria during pregnancy seen in the Routine iron group. The interim birth data suggested a longer hospital stay after birth and higher risk of negative fetal heart beat in the Routine iron group. However, all these differences were statistically non-significant and the complete birth data are needed to conclude any putative effects of iron on birth outcomes.

One of the strengths of our trial is its large sample. So far, this represents the largest trial investigating the benefits of prophylactic iron during pregnancy on MCH in malaria-endemic settings. The compliance of the study nurses with the trial protocol and that of the women with regard to uptake of the iron and folic acid tablets was good, as was the follow-up during pregnancy.22 However, during pregnancy, we lacked objective measures of malaria; hence, our results may not reflect the putative effect of iron on clinical malaria. The collection of delivery data was challenging, resulting in up to an estimated 40% of missing birth data. We did not realise the extent of the problem until most deliveries had occurred. We are currently tracing the birth data using various methods (abstracting hospital records and death register data and calling women), with results to be reported separately after finalisation.

A comparison of our findings with previous studies conducted in malaria-endemic areas is problematic because of key differences: previous studies have compared iron versus no iron, and our study compares two policies of iron administration: routine prophylaxis versus screening and treatment. Nevertheless, studies from Nigeria11 and Gambia12 found no significant effect of iron prophylaxis on malaria; they had used a more reliable measure of malaria (clinical and parasitological analysis). A Ugandan study14 did not observe any effect of iron supplementation on the incidence of congenital malaria in the offspring. A Bangladeshi study10 found a difference in preterm delivery (less in the non-iron group), but no association was seen with the other outcomes examined, similar to the Nigerian study,11 including abortion, hypertension, eclampsia, postnatal complications, birth weight, Apgar scores, prematurity, development of diarrhoea at 6 weeks and perinatal mortality. Other benefits reported with iron prophylaxis include increased mean birth weight,12 14 reduced incidence of prematurity12 and increased birth length and Apgar score.13

Although more complete birth data are needed to reach firm conclusions, we can speculate that the potential for a higher incidence of unavailable delivery data in the Routine iron group may indicate that these women had more adverse outcomes, such as miscarriage and stillbirths, and consequently did not deliver in the expected health centres. Similarly, the higher likelihood of longer mother's hospital stay after birth in the Routine iron group may also be indicative of more problems at birth. Delivery by caesarean section did not explain the longer hospital stay as the estimate remained the same after excluding the births that occurred by caesarean section.

Anaemia has been associated with MCH risks,24–26 and the association between iron and increased risk of infections5–7calls for more definitive evidence on the benefits of iron prophylaxis during pregnancy in settings with increased infectious diseases where infections remain a major cause of maternal and child mortality.8 9 Our trial in Maputo, Mozambique is an attempt to investigate whether routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy is more effective than screening and treatment for anaemia in improving MCH in an area of endemic malaria and HIV.

Conclusions

These interim results from this pragmatic RCT indicate that routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy did not suggest better MCH outcomes than the policy of screening and treatment for anaemia. If anything, screening and treatment for anaemia appeared to be better. Complete birth data are needed for a firm conclusion. Which of the two methods, Routine or Selective iron prophylaxis, is more feasible will be discussed in later publications.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BIN, EH, ER and SP designed, analysed and wrote the paper. EH designed and was responsible for the conception of the PROFEG Trial. BC, CS, EH, FA, GS, JC, MD, MN, OA and SP participated in the planning of the PROFEG Trial and made substantial contribution to its execution and participated in interpreting the results and critically reviewing the manuscript. ER and OA were responsible for data preparation and cleaning.

Funding: The study was funded by two grants from the Academy of Finland (2004: 210631; 2010: 139191).

Competing interests : None.

Ethics approval: Mozambique Ministry of Health Ethics Committee (CNBS [Ref. 84/CNBS/06]). A positive statement was obtained from the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES) (now the National Institute for Health and Welfare), Helsinki, Finland (Dno 2571/501/2007). The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00488579.

Provenance and peer review : Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Statistical codes and dataset are available from the corresponding author bright.nwaru@uta.fi. Informed consent was not obtained for data sharing, but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

References

- 1.Peña-Rosas JP, Viteri FE. Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron+folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(4):CD004736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Merialdi M, Gulmezoglu AM, et al. Nutritional interventions during pregnancy for the prevention or treatment of maternal mortality and preterm delivery: an overview of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr 2003;133:1606–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lao TT, Tam KF, Chan LY. Third trimester iron status and pregnancy outcome in non-anaemic women: pregnancy unfavourably affected by maternal iron excess. Hum Reprod 2000;15:1843–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yip R. Significance of an abnormally low or high hemoglobin concentration during pregnancy: special consideration of iron nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:272S–9S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oppenheimer SJ. Iron and its relation to immunity and infectious disease. J Nutr 2001;131:616S–35S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prentice AM. Iron metabolism, malaria, and other infections: what is all the fuss about? J Nutr 2008;138:2537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gera T, Sachdev HP. Effect of iron supplementation on incidence of infectious illness in children: systematic review. BMJ 2002;325:1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 2005;365:891–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idemyor V. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malaria interaction in sub-Saharan Africa: the collision of two Titans. HIV Clin Trials 2007;8:246–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juncker T, Ameer S, Mmaum A, et al. A trial of iron and folate supplementation during pregnancy in Bangladesh. Abstract presented at the American Public Health Association, 2001, Atlanta, Georgia, USA [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming AF, Ghatoura GB, Harrison KA, et al. The prevention of anaemia in pregnancy in primigravidae in the guinea savanna of Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1986;80:211–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez C, Todd J, Alonso PL, et al. The effects of iron supplementation during pregnancy, given by traditional birth attendants, on the prevalence of anaemia and malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994;88:590–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preziosi P, Prual A, Galan P, et al. Effect of iron supplementation on the iron status of pregnant women: consequences for newborns. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:1178–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndyomugyenyi R, Magnussen P. Chloroquine prophylaxis, iron/folic-acid supplementation or case management of malaria attacks in primigravidae in western Uganda: effects on congenital malaria and infant haemoglobin concentrations. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2000;94:759–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christian P, Khatry SK, Katz J, et al. Effects of alternative maternal micronutrient supplements on low birth weight in rural Nepal: a double blind randomized community trial. BMJ 2003;326:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian P, West KP, Khatry SK, et al. Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant mortality: a cluster-randomized trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:1194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian P, Darmstadt GL, Wu L, et al. The effect of maternal micronutrient supplementation on early neonatal morbidity in rural Nepal: a randomized, control, community trial. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:660–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christian P, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, et al. Effects of prenatal micronutrient supplementation on complications of labor and delivery and puerperal morbidity in rural Nepal. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;106:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christian P, Stewart CP, LeClerq SC, et al. Antenatal and postnatal iron supplementation and childhood mortality in rural Neap: a prospective follow-up in a randomized, controlled community trial. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:1127–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christian P, Murray-Kolb LE, Khatry SK, et al. Prenatal micronutrient supplementation and intellectual and motor function in early school-aged children in Nepal . JAMA 2010;304:2716–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng L, Dibley MJ, Cheng Y, et al. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: double blind cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwaru BI, Parkkali S, Abacassamo F, et al. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial on routine iron prophylaxis during pregnancy in Maputo, Mozambique (PROFEG): rationale, desgin, and success. Matern Child Nutr. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dgedge M. Implementation of an insecticide Bednet programme for malaria prevention through the primary health care system in Mozambique [Doctoral thesis]. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müngen E. Iron supplementation in pregnancy. J Perinat Med 2003;31:420–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brabin BJ, Hakimi M, Pelletier D. An analysis of anemia and pregnancy-related maternal mortality. J Nutr 2001;131(Suppl):604S–15S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoltzfus RJ, Mullanny L, Black RE. Iron deficiency anaemia. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, et al. ,eds. Comparative auantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Vol 1 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004:163–209 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.