Abstract

Objective

To assess the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and dietary sodium intake, and to identify if the major dietary sources of sodium differ by socioeconomic group in a nationally representative sample of Australian children.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

2007 Australian National Children's Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey.

Participants

A total of 4487 children aged 2–16 years completed all components of the survey.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Sodium intake was determined via one 24 h dietary recall. The population proportion formula was used to identify the major sources of dietary salt. SES was defined by the level of education attained by the primary carer. In addition, parental income was used as a secondary indicator of SES.

Results

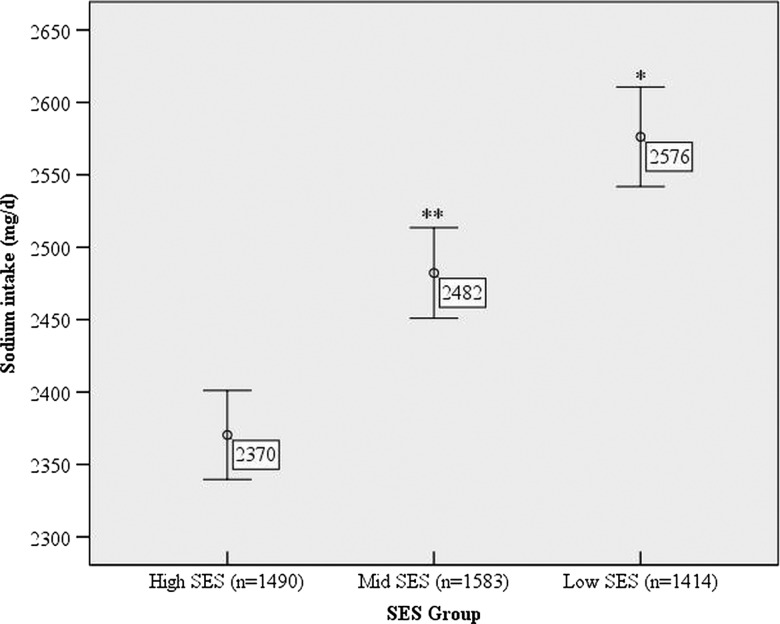

Dietary sodium intake of children of low SES background was 2576 (SEM 42) mg/day (salt equivalent 6.6 (0.1) g/day), which was greater than that of children of high SES background 2370 (35) mg/day (salt 6.1 (0.1) g/day; p<0.001). After adjustment for age, gender, energy intake and body mass index, low SES children consumed 195 mg/day (salt 0.5 g/day) more sodium than high SES children (p<0.001). Low SES children had a greater intake of sodium from processed meat, gravies/sauces, pastries, breakfast cereals, potatoes and potato snacks (all p<0.05).

Conclusions

Australian children from a low SES background have on average a 9% greater intake of sodium from food sources compared with those from a high SES background. Understanding the socioeconomic patterning of salt intake during childhood should be considered in interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Nutrition & Dietetics, Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

To assess the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and dietary sodium intake in Australian children and adolescents.

To determine if the major dietary sources of sodium differ by socioeconomic group.

Key messages

In Australian children, SES is inversely associated with dietary sodium intake.

Children of low socioeconomic background consumed more sodium from convenience style foods including pies/sausage rolls; savoury sauces, fried prepared potato; processed meat and potato crisps.

Strengths and limitations of this study

These results are based on a large nationally representative sample of Australian children and adolescents.

Sodium intake was determined via a 24 h dietary recall and therefore does not capture the amount of sodium derived from salt used at the table or during cooking.

The socioeconomic disparity of sodium intake reported in this study is attributable to differences in sodium intake from food sources only. Further research is required to understand how SES impacts on raising sodium intake.

Introduction

As in adults,1 dietary sodium intake is positively associated with blood pressure in children.2 3 Comparable to other developed nations,4 the dietary sodium intake of Australian children is high and exceeds dietary recommendations.5 6 Given that blood pressure follows a tracking pattern over the life course,7 8 it is very likely that high sodium consumption during childhood increases future risk of adult hypertension and subsequent cardiovascular disease (CVD). Increased CVD risk is also observed with low socioeconomic status (SES), 9 10 potentially due in part to differences in dietary intake. Furthermore, prolonged inequalities of SES across the life course are likely to accumulate to overall greater CVD risk,11 12 A number of studies in adults13–15 and in children and adolescents16–20 have identified SES as a determinant of diet quality. For instance, evidence from cross-sectional studies in children and adolescents have reported a positive association between SES and fruit and vegetable intake,17 18 21 and conversely, lower levels of SES have been associated with poor dietary outcomes, including a greater intake of high fat foods,20 fast foods and soft drinks.19 Studies examining the association between SES and sodium intake are scarce and inconsistent. One study in British adults found that low SES was associated with a higher intake of sodium,22 whereas in US adults, there was no association between SES and sodium intake.23 The aim of this study was to examine the association between SES and dietary sodium intake and the food sources of sodium in a nationally representative sample of Australian children aged 2–16 years.

Methods

Study design

The 2007 Australian Children's Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (CNPAS) was a cross-sectional survey designed to collect demographic, dietary, anthropometric and physical activity data from a nationally representative sample of children aged 2–16 years. The full details of the sampling methodology can be found elsewhere.24 Briefly, participants were recruited using a multistage quota sampling framework. The initial target quota was 1000 participants for each of the following age groups: 2–3, 4–8, 9–13 and 14–16 years (50% boys and 50% girls), to which a 400 booster sample was later provided by the state of South Australia. The primary sampling unit was postcode and clusters of postcodes were randomly selected as stratified by state/territory and by capital city statistical division or rest of state/territory. Randomly selected clusters of postcodes ensured an equal number of participants in each age group, from each of the metro and non-metro areas within each state. Within selected postcodes, Random Digit Dialling was used to invite eligible households, that is, those with children aged 2–16 years, to participate in the study. Only one child from each household could participate in the study. The response rate of eligible children was 40%. Owing to the non-proportionate nature of the sampling framework, each participant was assigned a population weighting which weighted for age, gender and region. The study was approved by the National Health and Medical Research Council registered Ethics Committees of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and the University of South Australia. All participants or, where the child was aged <14 years, the primary carer provided written consent.24

Assessments

Demographic and food intake data were collected during a face-to-face computer-assisted personal interview completed between February 2007 and August 2007. A three-pass 24 h dietary recall was used to determine all food and beverages consumed from midnight to midnight on the day prior to the interview.24 The three-pass method includes the following stages: (1) providing a quick list of all foods and beverages, (2) a series of probe questions relevant to each quick list item to gather more detailed information on the time and place of consumption, any additions to the food item, portion size and brand name and (3) finally, a recall review to validate information and make any necessary adjustments. Portion sizes were estimated using a validated food model booklet and standard household measures. To minimise error after data collection, all interviews were reviewed by study dieticians to assess for unrealistic portion sizes, inadequate detail and typing errors. The primary carer of participants aged 9 years and under provided information on dietary intake.24

Sodium intake was calculated using the Australian nutrient composition database AUSNUT2007, specifically developed by the Food Standards Australia and New Zealand for the CNPAS.25 The food coding system used in this database has previously been described.26 Daily sodium (mg) intake was converted to the salt equivalent (g) using the conversion 1 gram of sodium chloride (salt)=390 mg sodium. The reported salt intake did not include the salt added at the table or during cooking.

Indicator of socioeconomic status

Consistent with the other dietary studies in children and adolescents, we have used the level of education attained by the primary carer and household income as markers of SES.27 28 The highest level of education attained by the primary carer was used to define SES. Based on this, participants were grouped into one of three categories of SES: (1) high: includes those with a university/tertiary qualification, (2) mid: includes those with an advanced diploma, diploma or certificate III/IV or trade certificate and (3) low: includes those with some or no level of high school education. Parental income was used as a secondary indicator of SES. Reported parental income before tax was grouped into four categories (1) AUD$ 0 to $31 999, (2) $31 200 to $51 999, (3) $52 000 to $103 999 and (4) ≥$104 000. Body weight and height were measured using standardised protocols.29 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of body height (m2). Participants were grouped into weight categories (very underweight, underweight, healthy weight, overweight, obese) using the International Obesity Task Force BMI reference cut-offs for children.30 31

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using STATA/SE V.11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and PASW Statistics V.17.0 (PASW Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design using the STATA svy command, specifying the strata variable (region), cluster variable (postcode) and population weighting (age, gender and region). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (SD) or n (% weighted). Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between sodium intake, energy intake and BMI. To assess the association between SES, as defined by primary carer education level, and sodium intake, multiple regression analysis was used with adjustment for age, gender, energy intake and BMI. To further control for the effects of age, the analysis was repeated stratified by the age group (ie, 2–3; 4–8; 9–13; 14–16 years). These age categories are consistent with those used in Australian dietary guidelines6. As income level is sometimes used as a marker of SES, 13 the association between parental income and sodium intake was also examined, with adjustment for age, gender, energy intake and BMI. The regression coefficient (β) with 95% CI, corresponding p values and the coefficient of determination (R2) are presented. In a previous analysis26 which included the same study population, we used the population proportion formula32 to calculate the contribution of sodium from submajor food group categories, as defined in the CNPAS food group coding system.24 The population proportion formula32 is outlined below:

For the present study, we have utilised this list, which identifies the main sources of dietary sodium, to determine if sodium intake from the food group differs between low and high SES categories, based on primary carer education level. To do this, we calculated the mean sodium intake from each submajor food group by SES category, and compared the mean sodium of low with high SES, using an independent t test.

Results

Basic characteristics of the 4487 participants are listed in table 1. As defined by parental education status, the proportion of children from low, medium and high SES backgrounds was relatively evenly distributed. Over two-thirds of children fell within the two highest income bands. There was a significant positive correlation between sodium intake and energy intake (r=0.69, p<0.001) and sodium intake and BMI (r=0.22, p<0.001). Average daily sodium intake differed by SES (figure 1, p<0.01). Regression analysis indicated that low SES was associated with a 195 mg/day (salt 0.5 g/day) greater intake of sodium. The association between SES and sodium intake remained after adjustment for age, gender, energy intake and BMI (table 2). When stratified by the age group, the association between sodium intake and SES remained significant between the ages of 4–13 years (table 2); however, there was no association between sodium intake and SES in 2-year-olds to 3-year-olds or in 14-year-olds to 16-year-olds (data not shown). There was no association between sodium intake and parental income (data not shown); however, only 28% of children fell within the two lowest income bands (table 1). Table 3 lists those submajor food groups which contributed >1% to the groups’ total daily sodium intake. Combined, these 23 food groups accounted for 84.5% of the total daily sodium intake. Regular breads and bread rolls contributed the most sodium (13.4%). Moderate sources of sodium, contributing more than 4% of the total sodium intake, included mixed dishes where cereal is the major ingredient (eg, pizza, hamburger, sandwich, savoury rice and noodle-based dishes), processed meat, gravies and savoury sauces, pastries, cheese and breakfast cereals and bars. Compared with children of high SES, children of low SES had a significantly greater intake of sodium from processed meat, gravies and savoury sauce, pastries, breakfast cereals and bars, potatoes and potato snacks (eg, potato crisps). The percentage difference in sodium intake in each of these categories was 46%, 31%, 24%, 16%, 39% and 46%, respectively (table 3). Conversely, children of high SES background had a significantly greater intake of sodium from the food group containing cakes, buns, muffins, scones, cake-type desserts, and from the food group described as batter-based products (eg, pancakes and picklets). The percentage difference in sodium intake in each of these categories was 16% and 32%, respectively (table 3).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of Australian children and adolescents aged 2–16 years (n = 4487)

| Characteristic | n or mean | Per cent or SD |

|---|---|---|

| Male (n %) | 2 249 | 51 |

| Age (years) (mean SD) | 9.1 | 4.3 |

| Age group (years) (n %) | ||

| 2–3 | 1071 | 12 |

| 4–8 | 1216 | 34 |

| 9–13 | 1110 | 33 |

| 14–16 | 1090 | 21 |

| Socioeconomic status (n %)* | ||

| Low SES | 1414 | 30 |

| Medium SES | 1583 | 36 |

| High SES | 1490 | 34 |

| Parental income (n %)† | ||

| $0–31999 | 500 | 11 |

| $32000–51999 | 732 | 17 |

| $52000–103999 | 1850 | 42 |

| $≥104000 | 1169 | 30 |

| Weight status (n %)‡ | ||

| Underweight | 212 | 5 |

| Healthy weight | 3267 | 72 |

| Overweight | 761 | 17 |

| Obese | 247 | 6 |

| Energy (kJ/day) (mean SD) | 8392 | 3156 |

| Sodium (mg/day) (mean SD) | 2473 | 1243 |

| Salt equivalent (g/day) (mean SD)§ | 6.3 | 3.1 |

*SES as defined by the highest level of education attained by the primary carer.

†Participants with missing information for parental income (n=236) excluded.

§Salt equivalents (ie, sodium chloride: 1 g=390 mg sodium).

BMI, body mass index; SES, socioeconomic status.

Figure 1.

Mean sodium intake (mg/day) by socioeconomic group (n=4487)*Significantly different from high socioeconomic status (SES) (p < 0.001). **Significantly different from high SES (p< 0.05). †SES as defined by the highest level of education attained by the primary carer.

Table 2 .

Association between socioeconomic status (SES) and dietary sodium intake (390 mg/day) (1 g/day salt) in Australian children and adolescents aged 2–16 years (n = 4 487)*†

| Variable | Total sample (n=4 487) | Age group‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–8 years (n=1 216) | 9–13 years (n=1 110) | |||||

| β (95% CI) | p Value | β (95% CI) | p Value | β (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Unadjusted | ||||||

| High SES (reference) | ||||||

| Medium SES | 0.3 (0.03 to 0.5) | 0.03 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.6) | 0.17 | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | 0.319 |

| Low SES | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.1 to 1.0) | 0.02 | 0.5 (−0.02 to 1.0) | 0.06 |

| R2=0.004 | <0.01 | R2=0.008 | 0.05 | R2=0.004 | 0.16 | |

| Adjusted§ | ||||||

| High SES (reference) | ||||||

| Medium SES | 0.2 (0.01 to 0.4) | 0.04 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.4) | 0.13 | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | 0.23 |

| Low SES | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.7) | <0.001 | 0.6 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.001 | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.0) | 0.01 |

| R2=0.49 | <0.001 | R2=0.37 | <0.001 | R2=0.36 | <0.001 | |

*Dependent variable is sodium intake in units of 390 mg/day (salt equivalent 1 g/day) and independent variable is SES entered as an indicator variable: high SES is the reference category.

†SES as defined by the highest level of education attained by the primary carer.

‡No association between salt intake and SES in age groups 2–3 and 14–16 years (models not shown).

§Adjusted for gender, age, energy intake and body mass index.

Table 3.

Dietary sources of sodium intake listed by their contribution to intake for the group and mean daily sodium intake by food group, by socioeconomic group*

| Food group | Total sample (n = 4487) | SES group† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n 1414) | Mid (n 1583) | High (n 1490) | |||

| Percentage of contribution to total daily sodium intake | Mean sodium (SD) mg/day | Mean sodium (SD) mg/day | Mean sodium (SD) mg/day | p Value‡ | |

| Regular breads and bread rolls | 13.4 | 340 (315) | 330 (300) | 324 (317) | 0.26 |

| Mixed dishes where cereal is the major ingredient | 8.7 | 214 (514) | 256 (616) | 172 (445) | 0.07 |

| Processed meat§ | 7.6 | 216 (464) | 180 (403) | 168 (368) | 0.02 |

| Gravies and savoury sauces¶ | 6.5 | 182 (385) | 166 (395) | 139 (354) | 0.01 |

| Pastries** | 4.9 | 135 (400) | 120 (352) | 109 (345) | 0.03 |

| Cheese | 4.6 | 114 (209) | 110 (190) | 116 (186) | 0.80 |

| Breakfast cereals and bars | 4.2 | 113 (176) | 101 (166) | 97 (161) | 0.03 |

| Dairy milk | 3.9 | 95 (106) | 94 (103) | 100 (98) | 0.25 |

| Herbs, spices, seasonings and stock cubes | 3.7 | 114 (482) | 75 (246) | 90 (301) | 0.31 |

| Sausages, Frankfurts and Saveloys | 2.9 | 79 (259) | 74 (136) | 61 (201) | 0.07 |

| Mixed dishes where poultry/game is the major component | 2.6 | 79 (268) | 59 (194) | 60 (238) | 0.09 |

| Soup (prepared, ready to eat) | 2.6 | 51 (288) | 74 (379) | 65 (282) | 0.25 |

| English-style muffins, flat breads and savoury sweet breads | 2.4 | 55 (158) | 58 (180) | 67 (181) | 0.17 |

| Cakes, buns, muffins, scones, cake-type desserts | 2.3 | 54 (153) | 52 (144) | 68 (176) | 0.02 |

| Savoury biscuits | 2.2 | 49 (136) | 57 (147) | 57 (152) | 0.34 |

| Yeast, yeast, vegetable and meat extracts | 2.0 | 47 (117) | 55 (143) | 45 (108) | 0.70 |

| Potatoes†† | 1.9 | 53 (128) | 51 (127) | 38 (106) | 0.01 |

| Batter-based products‡‡ | 1.7 | 38 (161) | 37 (150) | 50 (180) | 0.05 |

| Potato snacks | 1.7 | 51 (149) | 40 (121) | 35 (125) | 0.03 |

| Pasta and pasta products | 1.4 | 35 (142) | 32 (130) | 35 (138) | 0.89 |

| Sweet biscuits | 1.2 | 29 (64) | 33 (72) | 27 (62) | 0.61 |

| Mixed dishes where beef, veal or lamb is the major component | 1.1 | 32 (175) | 21 (116) | 28 (56) | 0.53 |

| Mature legumes and pulse products and dishes | 1.0 | 21 (149) | 21 (137) | 35 (258) | 0.12 |

*Includes those submajor food group categories that contribute >1% of sodium to daily intake ambiguous.

†SES as defined by the highest level of education attained by the primary carer.

‡Means are compared between low and high SES groups using independent t test.

§Includes ham, bacon and processed delicatessen meat.

¶Includes pasta sauces and casserole bases.

**Includes pies and sausage rolls. ††Includes potato gems and wedges.

‡‡Includes pancakes and pikelets.

SES, socioeconomic status.

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample of Australian children aged 2–16 years, we found that children of low SES background consumed 9% more dietary sodium from food sources than those of high SES background. The inverse association between sodium intake and SES was primarily driven by the association in children aged 4–13 years, particularly after adjustment for the important covariates age, gender, energy intake and BMI. In adult studies, low SES has been associated with more frequent consumption of high salt foods, such as soup, sauces, ready-to-eat meals, savoury seasonings, sausages and potato.33 34 Given the parental control over children's food choices during these years, it is likely that SES disparities in adult food choices relating to high-salt foods may filter down into children's eating practices. We found no association between SES and sodium intake in 2-year-olds to 3-year-olds and 14-year-olds to 16-year-olds. Although some evidence indicates that SES disparities in dietary patterns may be present during infancy,35 it is possible that such early differences are not seen in dietary patterns with the restricted range of food types. In the case of adolescents, as autonomy over food choices increases, other factors, such as peer influence, taste and eating away from the home,36 may become more prominent determinants of dietary intake.

Using US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, Mazur et al37 explored the association of SES, as indicated by the head of household education status and household income, on sodium intake in Hispanic children aged 4–16 years. Interestingly, in this study, lower levels of education were associated with lower sodium intake.37 This is in contrast to our own findings as well as past studies, which generally link lower SES to overall poorer dietary outcomes.13 We found no association between sodium intake and level of income; however, low-income bands were under-represented. This is in contrast to the findings in Hispanic children, where low household income was associated with a greater intake of dietary sodium.37 In a New Zealand food survey, low-cost ‘home brand’-labelled food products were found to contain greater quantities of sodium than the more expensive branded food products.38 The impact of income on sodium intake in Australian children remains unclear and further research is required.

Previous studies in children have reported socioeconomic differences in the consumption of certain food groups.39 40 For example, in European children of low SES background, greater intake of starchy foods, meat products, savoury snacks such as hamburgers, sugar and confectionery, pizza, desserts and soft drinks have been reported.39 40 In the present study, those food groups which were found to contribute more sodium to the diets of low SES children tended to include convenience style foods (ie, pies/sausage rolls; savoury sauce and casserole base sauces; fried prepared potato; processed meat and potato snacks). Comparably, children of high SES background consumed greater amounts of sodium from cake-type and baked-type products. However, a significant amount of sodium in baked products can be in the form of sodium bicarbonate rather than sodium chloride. Sodium bicarbonate, unlike sodium chloride, has not been directly associated with adverse blood pressure outcomes.41

With reference to sodium intake data by age group5 and in comparison to the recommended daily upper limit of sodium,6 it is evident that Australian children of all ages across all SES backgrounds are consuming too much dietary sodium. However, for the first time, our findings indicate that socioeconomic disparities exist in sodium intake in Australian children aged 9–13 years. To reduce sodium intake in children, a comprehensive approach is required: first, targeting food policy to encourage product reformulation of lower sodium food products across all price ranges within the food supply. Second, consumer education and awareness campaigns that encourage food choices which are based on fresh products with minimal processing; this may require strategies that equip parents with enhanced food preparation skills and knowledge of the ‘hidden’ salt added to many commonly eaten processed foods. Furthermore, it is apparent that these strategies need to reach lower SES groups.

The major strengths of this study include the use of a large nationally representative sample of Australian children, with a comprehensive and standardised collection of dietary intake. Limitations of the study include the use of a 24-h dietary recall to assess sodium intake. First, this method fails to capture the amount of salt derived from salt added at the table and during cooking and therefore is likely to underestimate the true value of salt intake.42 The majority (77%) of dietary sodium consumed is from salt added to processed foods, while a smaller amount (11%) has been found to be derived from salt added at the table and during cooking.43 In the present study, the higher intake of sodium reported in children from low SES background is attributable to differences in sodium intake from food sources only. In a previous analysis of these data, we found that children from low SES background (33%) were more likely to report adding salt at the table than children from high SES (25%).26 Thus, it is likely that children of low SES background are consuming greater amounts of total daily sodium than reported in the present analysis. Second, the assessment of sodium intake is limited by the quality of food composition databases, which may not capture the variation in sodium content of different brand products within each food group. 42 44

In summary, the findings of higher salt intake from food sources in children of lower SES background, within a nationally representative sample, provide focus for concern regarding salt-related disease across the life course. This socioeconomic patterning of salt intake may, in turn, influence the SES disparity seen in hypertension and cardiovascular risk in adulthood. To reduce the socioeconomic inequalities in health, interventions need to begin early in life and should include product reformulation of lower sodium food products across all price ranges, as well as consumer education and awareness campaigns which reach low SES groups.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The author's responsibilities were as follows—CAG, KJC, LJR and CAN designed the research; CAG performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript and is also the guarantor of the paper; LJR, KJC and CAN helped with data interpretation, revision of the manuscript and provided significant consultation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a postgraduate scholarship from the Heart Foundation of Australia PP 08M 4074.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: Carley Grimes had financial support in the form of a postgraduate scholarship from the Heart Foundation, Australia for the submitted work and had no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Karen Campbell had no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Caryl Nowson has received research funds from Meat & Livestock Australia; National Health and Medical Research Council, Wicking Foundation, National Heart Foundation, Australia, Helen MacPerhson Smith Trust and Red Cross Blood Bank. These payments are unrelated to the submitted work. Lynn Riddell has received research funds from Meat & Livestock Australia. These payments are unrelated to the submitted work.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval : National Health and Medical Research Council registered Ethics Committees of Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and the University of South Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dickinson BD, Havas S. Reducing the population burden of cardiovascular disease by reducing sodium intake. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1460–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Importance of salt in determining blood pressure in children meta-analysis of controlled trials. Hypertension 2006;48:861–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He FJ, Marrero NM, MacGregor GA. Salt and blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hum Hyperten 2008;22:4–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, et al. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:791–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Food and Grocery Council, Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey—main findings. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/66596E8FC68FD1A3CA2574D50027DB86/$File/childrens-nut-phys-survey.pdf (accessed 12 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health and Medical Research Council Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra:Australian Government; Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n35.pdf (accessed 12 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood—a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation 2008;117:3171–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toschke AM, Kohl L, Mansmann U, et al. Meta-analysis of blood pressure tracking from childhood to adulthood and implications for the design of intervention trials. Acta Paediatrica 2010;99:24–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation 1993;88:1973–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosengren A, Subramanian SV, Islam S, et al. Education and risk for acute myocardial infarction in 52 high, middle and low-income countries: INTERHEART case-control study. Heart 2009;95:2014–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loucks EB, Lynch JW, Pilote L, et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of coronary heart disease: the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:829–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollitt RA, Rose KM, Kaufman JS. Evaluating the evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2005;5:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giskes K, Turrell G, Patterson C, et al. Socio-economic differences in fruit and vegetable consumption among Australian adolescents and adults. Public Health Nutr 2002;5:663–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulshof KFAM, Brussaard JH, Kruizinga AG, et al. Socio-economic status, dietary intake and 10 y trends: the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:128–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrosini GL, Oddy WH, Robinson M, et al. Adolescent dietary patterns are associated with lifestyle and family psycho-social factors. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:1807–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haapalahti M, Mykkanen H, Tikkanen S, et al. Meal patterns and food use in 10- to 11-year old Finnish children. Public Health Nutr 2002;6:365–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, et al. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents findings from project EAT. Prev Med 2003;37:198–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Utter J, Denny S, Crengle S, et al. Socio-economic differences in eating-related attitudes, behaviours and enviornments of adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2010;14:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardle J, Jarvis MJ, Steggles N, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in cancer-risk behaviours in adolescence: baseline results from the Health and Behaviour in Teenagers Study (HABITS). Prev Med 2003;36:721–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, et al. Demographic and socio-economic factors related to food intake and adherence to nutritional recommendations in a cohort of pre-school children. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:1096–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates CJ, Prentice A, Cole TJ, et al. Micronutrients: highlights and research challenges from the 1994–5 National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. Brit J Nutr 1999;82:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerber AM, James SA, Ammerman AS, et al. Socioeconomic status and electrolyte intake in black adults: the Pitt country Study. Am J Public Health 1991;81:1608–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health and Ageing User Guide 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Canberra:2010. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/AC3F256C715674D5CA2574D60000237D/$File/user-guide-v2.pdf (accessed 10 May 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Food Standards Australian and New Zealand (Internet) Canberra: Food Standards Australia and New Zealand; (cited Jan 23 2009). http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/ausnut2007/ (accessed 16 Nov 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimes CA, Campbell KJ, Riddell LJ, et al. Sources of sodium in Australian children’s diets and the effect of the application of sodium targets to food products to reduce sodium intake. Br J Nutr 2011;105:468–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron AJ, Ball K, Pearson N, et al. Socioeconomic variation in diet and activity-related behaviours of Australian children and adolescents aged 2–16 years. Pediatr Obes 2010;7:329–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golley RK, Hendrie GA, McNaughton SA. Scores on the dietary guideline index for children and adolescents are associated with nutrient intake and socio-economic position but not adiposity. J Nutr 2011;141:1340–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, Stewart A, et al. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Potchefstroom, South Africa: International standards for anthropometric assessment, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole TJ. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. Br Med J 2000;320:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, et al. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. Br Med J 2007;335:194–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs-Smith SM, Kott PS, Guenther PM. Mean proportion and population proportion: two answers to the same question? J Am Diet Assoc 1989;89:667–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purdy J, Armstrong G, McIlveen H. The influence of socio-economic status on salt consumption in Northern Ireland. Int J Consum Stud 2002;26:71–80 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Veen JE, Graaf CD, Van Dis SJ, et al. Determinants of salt use in cooked meals in the Netherlands: attitudes and practices of food preparers. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999;53:388–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okubo H, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, et al. Dietary patterns in infancy and their associations with maternal socio-economic and lifestyle factors among 758 Japanese mother–child pairs: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Matern Child Nutr 2012;8doi:10.1111/j.740-8709.2012.00403.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviours. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102:S40–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazur RE, Marquis GS, Jensen HH. Diet and food insufficiency among Hispanic youths: acculturation and socioeconomic factors in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:1120–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monro D, Young L, Wilson J, et al. The sodium content of low cost and private label foods; implications for public health. J N Z Diet Assoc 2004;58:4–10 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lioret S, Dubuisson C, Dufour A, et al. Trends in food intake in French children from 1999 to 2007: results from the INCA (etude Individuelle Nationale des Consommations Alimentaires) dietary surveys. Br J Nutr 2010;103:585–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sausenthaler S, Standl M, Buyken A, et al. Regional and socio-economic differences in food, nutrient and supplement intake in school-age children in Germany: results from the GINIplus and the LISAplus studies. Public Health Nutr 2011;10:1724–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarty MF. Should we restrict chloride rather than sodium? Med Hypotheses 2004;63:138–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loria CM, Obarzanek E, Ernst ND. The dietary guidelines: surveillance issues and research needs. Choose and prepare foods with less salt: dietary advice for all Americans. J Nutr 2001;131:536S–51S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattes RD, Donnelly D. Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr 1991;10:383–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization Creating an enabling enviornment for population-based salt reduction strategies. UK: World Health Organization, 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500777_eng.pdf. (accessed 10 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.