Abstract

Objective

To describe trends in new drugs launched in the UK from 1982 to 2011 and test the hypothesis that the rate of new drug introductions has declined over the study period. There is wide concern that pharmaceutical innovation is declining. Reported trends suggest that fewer new drugs have been launched over recent decades, despite increasing investment into research and development.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting and data source

Database of new preparations added annually to the British National Formulary (BNF).

Main outcome measures

The number of new drugs entered each year, including new chemical entities(NCEs) and new biological drugs, based on first appearance in the BNF.

Results

There was no significant linear trend in the number of new drugs introduced into the UK from 1982 to 2011. Following a dip in the mid-1980s (11–12 NCEs/new biologics introduced annually from 1985 to 1987), there was a variable increase in the numbers of new drugs introduced annually to a peak of 34 in 1997. This peak was followed by a decline to approximately 20 new drugs/year between 2003 and 2006, and another peak in 2010. Extending the timeline further back with existing published data shows an overall slight increase in new drug introductions of 0.16/year over the entire 1971 to 2011 period.

Conclusions

The purported ‘innovation dip’ is an artefact of the time periods previously studied. Reports of declining innovation need to be considered in the context of their timescale and perspective.

Keywords: Innovation, Pharmaceutical, New drugs, Drug launches, United Kingdom

Article summary.

Article focus

There is wide concern that pharmaceutical innovation is declining. Reported trends suggest that fewer new drugs have been launched over recent decades, despite increasing investment in R&D.

Key messages

While there are dips and peaks during specific time periods, the longer term trend contradicts the widely held view that pharmaceutical innovation is declining, suggesting that the annual numbers of newly launched drugs may have increased since the early 1970s.

It is important to take into account the start and end dates included in analyses when interpreting time trends.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the most up-to-date study of trends in the launch of new drugs in the UK, using 30 years of complete data. The results are consistent with data on the US and worldwide drug launches.

Although the numbers of new chemical entities (NCEs) and new biological agents launched are a useful indicator of trends in pharmaceutical innovation, they are not the sole metric. Our data do not differentiate between varying degrees of novelty or clinical importance, which may represent different levels of innovation.

Introduction

Despite increasing pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) times, costs and spending,1–5 there are concerns that these increasing efforts are not being reflected in the numbers of new drugs being brought to the market. Indeed, it is widely reported that there has been a decline or dip in the rate of development of new drugs over recent decades.1 6–10 Within the context of drug development, a new innovation is generally defined as the discovery, development and bringing to the market of a new chemical entity (NCE)11; ‘an active ingredient that has never been marketed…in any form’.12 These new entities may be relatively minor modifications of existing drugs or represent radical new breakthroughs.

Much of the evidence for an ‘innovation dip’ comes from North America. Data from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) show a downward trend in the number of NCEs introduced throughout the 1990s and at the start of the new millennium,13 14 with the 18 new medicines approved in 2007 representing ‘the lowest figure in a quarter of a century’.1 A decrease has also been noted in patented medicines granted market access in Canada between 1997 and 2008.15 Worldwide data also indicate a decline in NCE introductions between 1982 and 2002/200316 17; however, studies that include earlier decades suggest that this may be an artefact of a peak in 1996, with a return to historic levels thereafter.5 18–20 More recent trends also show an increase in new biological agents5 13 16 18 and orphan products,16 which suggests a shift in the focus of innovation. Papers focusing specifically on the UK report a decline in NCEs launched from 1960 to the late 1980s,2 21 22 although the downward trend is considerably weakened by omitting the years 1960–1963.22 The numbers of NCEs authorised in the UK between 1972 and 1994 also show no consistent annual trend, although there was an increase in authorisations of new biological entities and products of biotechnology.23 By contrast, the numbers of all newly launched medicines, including new formulations of existing drugs and generic drugs, show no decline in new product introductions in the UK subsequent to the implementation of the Medicines Act 1968 in 1971, though there had been a fall in new drugs launched in the early 1960s following the thalidomide tragedy.22 However, even though there is disagreement on the crude rate of drug launch, it does at least seem certain that the rate per R&D spend has declined. Scannell et al10 calculated that the rate of new drugs per billion dollars spent on R&D (adjusted for inflation) has halved approximately every 9 years since the 1950s.

We aimed to test the widely held belief that the annual numbers of new drugs launched in the UK have declined or are declining. After the USA, the UK is the next largest source of NCE development, accounting for 10.4% of pharmaceutical innovation worldwide.24 It is recognised that, prior to the implementation of the Medicines Act 1968, there was no formal licensing of medicines in the UK, other than those covered by the Therapeutic Substances Act 19562; earlier evidence suggests that the Medicines Act 1968 would have slowed or even prevented some product introductions from the early 1970s onwards.22 New drugs include both NCEs and new biological agents, which are medicinal products created by biological processes rather than chemical synthesis. New biologics include vaccines, blood products, allergenic extracts, somatic cells, gene therapies, tissues, recombinant therapeutic proteins or living cells used therapeutically.25 We primarily considered the period from 1982 to 2011, but also incorporated existing published UK data2 21 22 in order to consider the entire period from the implementation of the Medicines Act 1968 in 1971.

Methods

Data collection and classification of entries

We obtained data on the numbers of new drugs (NCEs and new biological agents) launched in the UK each year from relevant editions of the British National Formulary (BNF). The BNF lists all preparations available for prescribing and/or dispensing in the UK, including prescription-only and over-the-counter medicines, not all of which are available on the National Health Service (NHS). Information on the active ingredient for every item in the ‘new preparations’ section of each edition of the BNF from edition 3 in 1982 to edition 62 in 2011 was obtained and entered onto a database. As the BNF also includes non-drug products, these were excluded (nutraceutical and medical foods, natural products, devices and diagnostic products—definitions are given in the online supplementary appendix 1) leaving only drugs (NCEs, existing chemical compounds, new salts or esters of existing chemical compounds, new biological agents and existing biological agents). Different dosages of the same product (eg, 5 and 10 mg tablets) were counted once; different formulations of the same product, for example, tablet and intramuscular injection were counted once if they contained the same active ingredients, and multiple times if they contained different active ingredients. Different indications for the same product were counted once.

Definition of new drugs

Entries were classified as new (NCE or new biological agent) by checking whether the drug substance appeared in previous editions of the BNF. New formulations, generic versions and new salts or esters of existing drugs were therefore not classified as new. Commercial pharmaceutical databases (PharmaProjects V.5.2, Informa Healthcare and Adis R&D Insight, Wolters Kluwer Pharma Solutions) were also used to determine whether a substance was a new drug at the date of the UK launch. Where preparations could not be found in commercial pharmaceutical databases, we undertook internet searches for scientific articles or patents relating to the substances.

Analysis

Time trends in the numbers of new drugs introduced in the UK were analysed using linear regression (SPSS V.17.0, IBM). Year (1971–2011) was treated as a continuous variable. The primary analysis included all new drugs (NCEs and new biologics) added to the BNF from 1982 to 2011, with a subanalysis of the 1997–2006 decade for comparison with the published literature on worldwide NCE launches.16 Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test for homogeneity of regression before and after the 1997 peak, with a number of new drugs as the dependent variable and year as the covariate, grouped by the periods on either side of the peak (1982–1997 and 1998–2011). The secondary analysis incorporated existing published UK data to include all new drug introductions from 1971 to 2011. Data on NCE launches were originally reported by Lis and Walker2 using published sources including the BNF, the Monthly Index of Medical Specialties (MIMS; Haymarket Group) and Scrip (Informa), up to 1987; this was extended up to 1990 by the Centre for Medicines Research (CMR; now Centre for Medicines Research International, The Thomson Corporation, London).21 Where there was overlap (1982–1990), we took the average of the two values.

Results

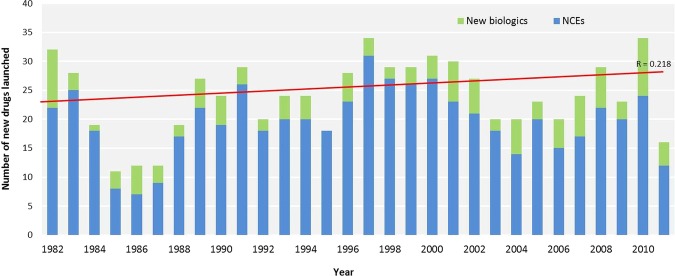

Analysis 1: new drugs launched from 1982 to 2011

Figure 1 shows the number of new drugs launched annually in the UK from 1982 to 2011. The mean number of new drugs introduced each year was 23.9 (SE 1.16). The lowest was 11 in 1985, and the highest was 34 in 1997 and again in 2010. These data suggest only a minor upward linear trend in the annual numbers of new drugs launched, a result that was not statistically significant (new drugs launched: y=− 291+0.16×year, r=0.22, p=0.25).

Figure 1.

New drugs launched in the UK from 1982 to 2011.

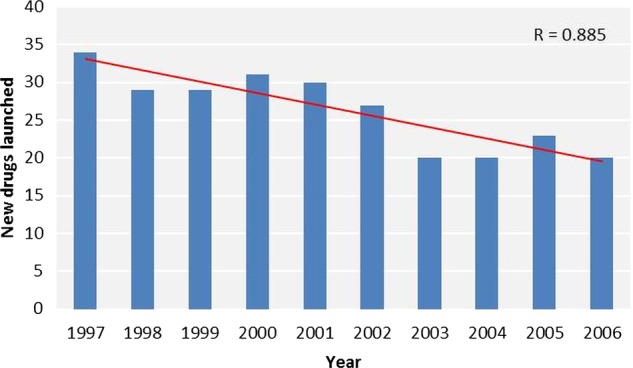

A subanalysis for the 1997–2006 decade (figure 2) revealed a statistically significant downward trend (new drugs launched: y=3047−1.51×year, r=0.89, p=0.001). ANCOVA showed no significant interaction between year and period (F1,26=2.68, p=0.11), indicating equality of regression slopes pre-1997 and post-1997. There was a significant positive first-order autocorrelation in the residuals (Durbin-Watson statistic=1.09, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

New drugs launched between 1997 and 2006.

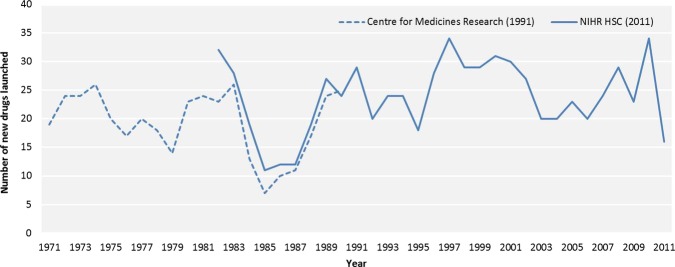

Analysis 2: new drugs launched from 1971 to 2011

This analysis used new drug data collected for this study from the BNF and NCE data from the CMR to extend our timeline back to 1971 (figure 3). The mean number of new drugs introduced each year was 22.7 (SD 6.0). The lowest was 9 in 1985, and the highest was 34 in 1997 and 2010. These data showed a modest upward linear trend in the annual numbers of new drugs launched between 1971 and 2011, a result that was statistically significant. In addition, the rate of annual increase was very similar to that seen in our data for the period 1982–2011 (new drugs launched: y=− 296+0.16×year, r=0.32, p=0.04). Again, ANCOVA revealed no interaction between year and period, indicating equality of regression slopes pre-1997 and post-1997 (F1,37=2.35, p=0.13). There was a significant positive first-order autocorrelation in the residuals (Durbin-Watson statistic=1.10, p<0.01).

Figure 3.

New drugs launched in the UK from 1971 to 2011.

Discussion

This is the most complete study of the number of new drug introductions in the UK, with 30 years complete data on new products. The BNF includes all medicinal products available for dispensing in the UK and is updated every 6 months, providing an accurate and reliable account of new drugs launched in the UK each year. We found no statistically significant linear trend in new drug introductions between 1982 and 2011; however, a statistically significant, though modest, upward trend was observed after extending the data further to include the years 1971 to 1981,21 22 contradicting the widely held view that the number of new medicines being launched is declining. Although there was indeed a dip in new drug introductions during the decade from 1997 to 2006, this was largely an artefact of a peak in 1997, which was itself preceded by an unusually low number of launches in 1985–1987. Additionally, the peak number of new drugs added to the BNF in 1997 was matched in 2010.

The main limitation of the study is that it only describes trends in the launch and cannot attribute causes to changes; nor do we here disaggregate the data to explore different trends for different treatments and different disease groups. Nonetheless, there are key events during the timeline that should be noted, as they may provide some insight into the observed trends. Despite the implementation of the Medicines Act 1968, it has been argued that the thalidomide crisis did not lead to more rigorous drug regulation; instead, there was a culture of ‘reluctant regulation’ which was linked to trust and optimism concerning the safety of new drugs and avoiding potential conflicts with industry interest.26 27 This arrangement was disrupted by the practolol disaster of the early 1980s, which resulted in approximately 2,450 reports of adverse reactions, including 40 deaths,26 and the withdrawal of four NCEs worldwide in 1983 due to safety concerns2 28 and may partly explain the low number of new drugs launched during 1985–1987.27 The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products ((EMA) since 2004) was set up with funding from the European Union and the pharmaceutical industry to integrate the work of existing national medicine regulatory bodies, and may also have impacted upon new drug approvals and launches following its inception in 1995. Changes in drug review processes may partially account for the peak in new drugs launched in the mid-1990s, and the generally higher levels observed in the latter half of the timeline. For example, faster approval times by the FDA following the global AIDS epidemic29 and the introduction of the Prescription Drug User Fee Acts from 199230 may have influenced worldwide marketing approaches, including decisions to seek new drug licenses, while in Europe, a new review system implemented by the EMA in 2006 attempted to reduce approval times for innovative drugs offering significant clinical benefit.31 Increased innovation could also be driven by policy, such as the EU regulation on orphan medicinal products, which exists to stimulate research and development into drugs for rare conditions.31 32

We included all new drugs in the analysis, but did not separate these into ‘first-in-class’ and ‘me-too’ drugs, which arguably represent different levels of innovation and significance. It has been asserted that the true ‘innovation crisis’ is due to the majority of new drugs being chemically similar to existing ones and offering few therapeutic gains.19 Yet data from the FDA show that the percentage of priority products (ie, those that appear to represent an advance over available therapies)12 reached a 30-year high during 2005–2009, at almost 50% of total new drug approvals.20 We also excluded incremental innovation to existing drugs, such as new indications and formulations, which in some cases can be as important as new drug launches in terms of clinical and economic benefits.33 34 Berndt et al34 demonstrated an overall increase in the number of supplementary new drug approvals for new indications for three major drug classes (ACE inhibitors, histamine H2-antagonists/proton-pump inhibitors and selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) since the early 1990s, suggesting that the value of incremental innovation may be overlooked when assessing productivity trends for pharmaceutical R&D. Nevertheless, it should be noted that there is no standard framework for assessing the therapeutic value of drugs developed over such a broad time frame and variety of classes.24

The findings are consistent with published reports of decreasing drug introductions, but only during the mid-1990s to early 2000s.1 2 7 13 16 17 21 In particular, there was consistency with the CMR data for UK NCE launches up to 199021; minor variations were likely to be due to differences in the data sources used. However, the data do not show a longer term decline, but instead support more recent analyses, suggesting a return to historic levels following a peak around 1997.5 18–20 Clearly, the start and end dates included in analyses can influence the interpretation of time trends. Furthermore, the trend gradients for the present study data and the longer time trend are very similar, only reaching statistical significance with sufficient data points. Taken together, they indicate a gradual increase in the annual number of new drug introductions (approximately 0.16 new drugs per year). This is in line with a recent forecasting analysis, which predicts an increase in new drug launches in the 2012–2016 period compared with the previous 5 years to 2011.35

While the data do not show a reduction in absolute numbers of new drugs, it has been argued that the pharmaceutical industry has become less productive, as the number of new drugs launched has not increased relative to R&D time and expenditure or the availability of more advanced technology.5 7 10 21 36 The cost per new drug produced is estimated to have grown at an annual compound rate of 13.4% since the 1950s; adjusting for inflation (3.7% per year) and other cost increases such as regulation (8.3%/year) increases the estimated cost per new drug considerably.5 This may be a cause for concern, and certainly for disappointment in the pharmaceutical industry. Advances at the drug discovery stage (eg, the introduction of high-throughput screening in the late 1980s and early 1990s) in theory means that more new compounds can be investigated more quickly and the introduction of target-based drug discovery in the mid-1990s was a further promising breakthrough. However, drug development times have been increasing; the time taken to bring a new drug to the market rose from approximately 3 years in 19602 to 12 years at the start of the new millennium.3 Notwithstanding the EMA's (and FDA's) attempts to accelerate approvals, these may reflect more rigorous processes and requirements, and higher rejection rates in establishing the safety and efficacy of new drugs.7 It has also been suggested that we are approaching the scientific and economic limits of innovation,37 so there may be a ceiling limiting drug discovery.

The nature and context of pharmaceutical innovation have changed considerably over the last half century. We now need a further exploration of the detail of the nature of the drugs launched and of the events surrounding the innovation timeline to elucidate the factors underpinning the apparent steady state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Nuredin Mohammed for advising on the analysis for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AJS conceived the original study idea, and DJW, OIM, SS and AJS contributed to the development of the study design and methods. OIM collected the data and carried out the initial analysis; DJW, SS and AJS advised on the classification of entries and directed further analysis. All authors (DJW, OIM, SS and AJS) were involved in the interpretation of the results. OIM produced the initial draft of the paper, which was then circulated repeatedly to all authors for critical revision. DJW, OIM, SS and AJS read and approved the final version, and all contributed to making revisions in response to the reviewers’ comments. All authors had full access to all of the study data (including statistical reports and tables), and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. DJW is the guarantor.

Funding: The study was undertaken as part of the research programme of the NIHR Horizon Scanning Centre (NIHR HSC). The NIHR HSC is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The NIHR had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: DW, OM, SS and AS have support from the National Institute for Health Research for the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We have provided the data used to generate our figures and analyses, that is, numbers of new drugs launched each year from 1971 to 2011, stratified by type (NCEs and new biologics) from 1982 onwards. If you require any further information, please contact the corresponding author: o.i.martino@bham.ac.uk

References

- 1.Miller HI. Pharma innovation in critical condition. Genet Eng Biotechnol News 2009;29 http://www.genengnews.com/gen-articles/pharma-innovation-in-critical-condition/3115/ (accessed 8 Nov 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lis Y, Walker SR. Novel medicines marketed in the UK 1960–1987. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1989;28:333–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMasi JA. The value of improving the productivity of the drug development process: faster times and better decisions. Pharmacoeconomics 2002;20(Suppl):1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ 2003;22:151–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munos B. Lessons from 60 years of pharmaceutical innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009;8:959–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wurtman RJ, Bettiker RL. The slowing of treatment discovery, 1965–1995. Nat Med 1995;1:1122–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Innovation or stagnation: challenge and opportunity on the critical path to new medicinal products. 2004: http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/CriticalPathInitiative/CriticalPathOpportunitiesReports/ucm077262.htm (accessed 2 Feb 2012).

- 8.Charlton BG. Why medical research needs a new specialty of ‘pure medical science’. Clin Med 2006;6:163–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancet editorial Where will new drugs come from? Lancet 2011;377:9721215869 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scannell JW, Blanckley A, Boldon H, et al. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012;11:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House of Commons Health—Fourth Report. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200405/cmselect/cmhealth/42/4202.htm (accessed date 22 Mar 2012).

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Drugs@FDA glossary of terms. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ucm079436.htm (accessed 15 Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen FJ. Macro trends in pharmaceutical innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005;4:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debnath B, Al-Mawsawi LQ, Neamati N. Are we living in the end of the blockbuster era? Drug News Perspect 2010;23:670–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) The economic value of innovative health technologies. CADTH, 2011

- 16.Grabowski HG, Wang YR. The quantity and quality of worldwide new drug introductions, 1982–2003. Health Aff 2006;25:452–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenberg FR. Pharmaceutical innovation and the burden of disease in developing and developed countries. New York: Columbia University and the National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid EF, Smith AF. Keynote review: is declining innovation in the pharmaceutical industry a myth? Drug Discov Today 2005;10:1031–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Light D, Lexchin J. Pharmaceutical R&D: What do we get for all that money? BMJ 2012;345:22–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaitin KI, DiMasi JA. Pharmaceutical innovation in the 21st century: new drug approvals in the first decade, 2000–2009. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:183–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centre for Medicines Research Twenty five new chemical entities launched in the UK in 1990. CMR News 1991;9:4–8 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tansey IP, Armstrong NA, Walker SR. Trends in pharmaceutical innovation: the introduction of products on to the UK market, 1960–1989. J Pharm Med 1994;4:85–100 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferys DB, Leakey D, Lewis JA, et al. New active substances authorized in the United Kingdom between 1972 and 1994. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45:151–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyhani S, Wang S, Hebert P, et al. US pharmaceutical innovation in an international context. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1075–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Drugs@FDA Glossary of terms. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ucm079436.htm#B (accessed 15 Aug 2012).

- 26.Abraham J, Davis C. Testing times: the emergence of the practolol disaster and its challenges to British drug regulation in the modern period. Soc Hist Med 2006;19:127–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpenter D. Reputation and power: organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin JP, Weber JCP. Product licence delays. Int Pharm J 1987;1:232–3 [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) HIV specific resources. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/SpeedingAccesstoImportantNewTherapies/ucm181838.htm (accessed 19 Oct 2012).

- 30.Berndt ER, Gottschalk AHB, Philipson TJ, et al. Industry funding of the FDA: effects of PDUFA on approval times and withdrawal rates. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005;4:545–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahoo A. Drug approval trends at the FDA and EMEA: process improvements, heightened security and industry response, Business Insights, 2008. HIV specific resources. http://www.pharmatree.in/pdf/reports/Drug%20Approval%20Trends%20at%20the%20FDA%20and%20EMEA_Process%20improvements,%20heightened%20scrutiny%20and%20industry%20response.pdf (accessed 19 Oct 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Commission Orphan medicinal products. http://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/orphan-medicines/index_en.htm (accessed 19 Oct 2012).

- 33.Aronson JK. Drug development: more science, more education. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;59:377–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berndt ER, Cockburn IM, Grépin KA. The impact of incremental innovation in biopharmaceuticals: drug utilisation in original and supplemental indications. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24(Suppl 2):69–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berggren R, Møller M, Moss R, et al. Outlook for the next 5 years in drug innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012;11:435–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sams-Dodd F. Target-based drug discovery: is something wrong? Drug Discov Today 2005;10:139–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huebner J. A possible declining trend for worldwide innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2005;72:980–6 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.