Abstract

Objectives

Magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca) antagonise each other in (re)absorption, inflammation and many other physiological activities. Based on mathematical estimation, the absorbed number of Ca or Mg depends on the dietary ratio of Ca to Mg intake. We hypothesise that the dietary Ca/Mg ratio modifies the effects of Ca and Mg on mortality due to gastrointestinal tract cancer and, perhaps, mortality due to diseases occurring in other organs or systems.

Design

Prospective studies.

Setting

Population-based cohort studies (The Shanghai Women's Health Study and the Shanghai Men's Health Study) conducted in Shanghai, China.

Participants

74 942 Chinese women aged 40–70 years and 61 500 Chinese men aged 40–74 years participated in the study.

Primary outcome measures

All-cause mortality and disease-specific mortality.

Results

In this Chinese population with a low Ca/Mg intake ratio (a median of 1.7 vs around 3.0 in US populations), intakes of Mg greater than US Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) levels (320 mg/day among women and 420 mg/day among men) were related to increased risks of total mortality for both women and men. Consistent with our hypothesis, the Ca/Mg intake ratio significantly modified the associations of intakes of Ca and Mg with mortality risk, whereas no significant interactions between Ca and Mg in relation to outcome were found. The associations differed by gender. Among men with a Ca/Mg ratio >1.7, increased intakes of Ca and Mg were associated with reduced risks of total mortality, and mortality due to coronary heart diseases. In the same group, intake of Ca was associated with a reduced risk of mortality due to cancer. Among women with a Ca/Mg ratio ≤1.7, intake of Mg was associated with increased risks of total mortality, and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and colorectal cancer.

Conclusions

These results, if confirmed, may help to understand the optimal balance between Ca and Mg in the aetiology and prevention of these common diseases and reduction in mortality.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, NUTRITION & DIETETICS

Article summary.

Article focus

Modifying effects of the calcium/magnesium (Ca/Mg) intake ratio on the associations between the intakes of Ca and Mg with disease mortality.

The effect of high Mg intake on disease mortality differs in populations with a very low Ca/Mg intake ratio from those (ie, Western populations) with a high ratio.

Modifying effects of sex on the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg with disease mortality.

Key messages

Significant modifying effects of a Ca/Mg intake ratio, but not Mg or Ca intake alone, on the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg, respectively, with risk of total mortality and coronary heart diseases and possibly cancer.

In contrast to studies conducted in the USA, high intake of Mg was related to an increased risk of total mortality among both men and women at a similar Mg intake level but a low Ca/Mg intake ratio.

Sex significantly modified the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg with disease mortality.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Population-based prospective design with large sample sizes.

High rates for baseline participation and follow-up.

A unique population with a similar Mg intake, but a lower Ca/Mg intake ratio versus the US population.

Adjustment for many potential confounding factors.

Similar results in sensitivity analysis by excluding those who used Ca or multivitamin supplements.

Caution for the generalisation of findings to populations with a high Ca/Mg ratio.

The Ca and Mg contents of drinking water not included.

Small sample size in the analyses by cancer subtype, particularly among men.

Introduction

Magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca) belong to the same family in the periodic table and share the same homeostatic regulating system1 involving Ca sensing receptor (CaSR) and (re)absorption.2 Meanwhile, Mg and Ca antagonise each other in many physiological activities.2–8 It was not until recently that Mg was thought to share ion transporters with Ca in (re)absorption.9 Mg ion transporters identified in recent years (eg, TRPM7) also have affinity for Ca.9 In the intestine, Ca and Mg may directly or indirectly compete for intestinal absorption.2 A low concentration of Ca and a high concentration of Mg (thus, a low Ca : Mg) in the lumen activates mucosal transport of Mg.2 A high Ca intake reduces absorption rates for both Mg and Ca in humans.2 4

Colon lumen concentrations for Ca2+ and Mg2+ are monitored by the same receptor, the CaSR.1 If the body needs to absorb a total of 10 ions of Ca and Mg, and the diet contains 5 ions of Ca and 5 ions of Mg, all the 5 Ca ions and 5 Mg ions are absorbed. If the diet consists of 45 ions of Ca and 5 ions of Mg, 9 Ca ions and 1 Mg ion are absorbed. Thus, if the total absorbed number of Ca and Mg is relatively constant, the absorption number for Ca is dependent on Ca*(1/(Ca+Mg))=Ca/(Mg+Ca)=(Mg/Ca+1)−1, in which only the Mg/Ca ratio varies. It is also true in the case of Mg. Thus, we postulated that the dietary ratio of Ca to Mg modifies the effects of Ca and Mg intakes on carcinogenesis.10 11 In a study conducted in the USA, we found that a high intake of total Ca or Mg may only be related to a reduced risk of colorectal adenoma when the Ca/Mg ratio was below 2.78.10 In a randomised clinical trial conducted in the USA, Ca treatment only significantly reduced colorectal adenoma recurrence risk when the baseline dietary Ca/Mg ratio was under 2.63, and this effect modification by the Ca/Mg ratio cannot solely be attributed to the baseline dietary intake in either Ca or Mg.11 In another study, high serum Ca/Mg ratio was associated with an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer after controlling for serum Ca and Mg.12 However, all these studies have been conducted in high Ca/Mg ratio populations.

Many studies conducted in Western countries have linked low intake of Mg to insulin resistance13 and systemic inflammation14 and, thus, risk of diseases common in Western countries, such as metabolic syndrome,15 type II diabetes,16–18 coronary heart disease19–21 and cancer.10 22–24 East Asians have much lower incidence and death rates of coronary heart disease and colorectal cancer, but much higher rates of stroke compared with their counterparts in the USA. However, the mean intake of Mg25 26 in East Asia10 is equivalent to the US population27 whereas the Ca/Mg intake ratio is almost halved in the Chinese population compared to the US population.25 28 Thus, it is possible that the differential Ca/Mg intake ratio may contribute, in part, to the different incidence and death rates of these common diseases.10

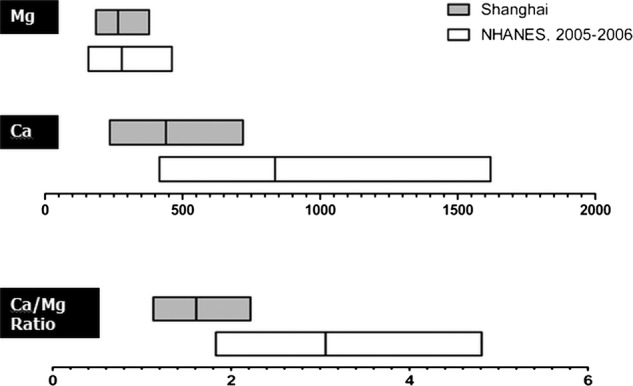

The US population's low Ca/Mg ratio range (defined as below the US median) overlaps with the high ratio range in the Chinese population (above the Chinese median; see figure 1). Thus, we further hypothesise that in Chinese populations, the intakes of Mg and Ca may only be related to a reduced risk of mortality due to colorectal cancer and, perhaps, other common diseases when the dietary Ca/Mg ratio is above the median (1.7). Conversely, previous studies indicate that a high Mg intake led to a negative Ca balance when the Ca intake was low (ie, low Ca/Mg ratio).29 Thus, a high Mg intake may have a detrimental effect when the Ca/Mg ratio is very low (below 1.7). We tested these hypotheses in two population-based cohorts conducted in China with over 130 000 participants.

Figure 1.

Comparison of intake levels of Ca (mg/day), Mg (mg/day) and Ca/Mg ratio in the USA and Shangai, China.

Methods

Shanghai Women's Health Study and Shanghai Men Health Study

The Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS) and the Shanghai Men Health Study (SMHS) are two prospective, population-based cohort studies conducted in urban Shanghai, China. In both studies, similar designs, which were described in detail elsewhere, were utilised.30 31 In brief, during 1996 and 2000, the SWHS recruited 74 942 women aged 40–70 years from seven urban communities, representative of urban Shanghai with a participation rate of 92.7%, whereas from 2002 to 2006, the SMHS enrolled 61 500 men aged 40–74 years from the same seven communities with a participation rate of 74.1%. Certified interviewers elicited information on demographic characteristics, medical history, anthropometrics, usual dietary habits, physical activities and other lifestyle factors. At least two measurements were conducted for weight, height and circumferences of the waist and hips at the inperson interview. The study was approved by all relevant institutional review boards in China (Shanghai Cancer Institute) and the USA (Vanderbilt University).

Cohort follow-up and outcome ascertainment

The SWHS and SMHS participants have been followed up by biennial home visits as well as annual record linkage to the population-based Shanghai Cancer Registry and Vital Statistics Registry. In the current study, the primary outcomes included deaths from all causes, deaths from cardiovascular diseases (including coronary heart diseases and stroke) and deaths from cancers occurring between the baseline recruitment and the most recent follow-up and/or annual vital status linkage. The follow-up rate for vital status in both cohorts was >99.9% complete.32 33 In this analysis, in order to allow for the delay in records processing, the date of the last follow-up was set as 31 December 2009 for study participants, 6 months before the most recent record linkage (30 June 2010). The underlying causes for deaths were determined based primarily on death certificates from the Shanghai Vital Statistics Registry which are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Studies have been conducted to validate cause-of-death statistics in urban China, which also includes urban Shanghai, and data on death certificates have shown reasonable accuracy for major causes of deaths including cancer and cardiovascular diseases.34

Exposure measurement and covariates

Usual dietary intakes were assessed through inperson interviews using validated food-frequency questionnaires (FFQs) in SMHS35 and SWHS.36 Nutrient intakes (ie dietary Ca and Mg) were derived from FFQs using the Chinese food composition tables (Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, China CDC, 2004). A wide array of covariates assessed at the baseline survey and FFQs were compared by levels of exposure (intake levels of Ca and Mg) as potential confounding factors (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline lifestyle factors and demographics by intakes of calcium and magnesium, the Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS) and the Shanghai Men Health Study (SMHS), 1996–2009

| Calcium (mg/day) |

Magnesium (mg/day) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <408 | 408–<600 | ≥600 | <251 | 251–<320 | ≥320 | |

| Shanghai Women's Health Study | ||||||

| Married (%) | 87.87 | 90.28 | 88.45 | 87.93 | 89.87 | 88.96 |

| Smokers (%) | 3.64 | 2.13 | 2.07 | 3.41 | 2.18 | 2.5 |

| Alcohol drinkers (%) | 2.08 | 2.17 | 2.7 | 2.11 | 2.08 | 2.7 |

| Tea drinker (%) | 24.84 | 32.23 | 36.22 | 26.09 | 31.4 | 34.24 |

| Ginseng use (%) | 25.01 | 30.35 | 34.85 | 26.75 | 29.94 | 31.55 |

| Ca supplement use (%) | 15.41 | 20.33 | 25.09 | 17.49 | 19.75 | 21.43 |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 3.98 | 8.1 | 11.68 | 5.74 | 7.52 | 8.77 |

| Physically active (%) | 30.12 | 36.06 | 43.32 | 31.78 | 35.64 | 39.79 |

| High school or up (%) | 8.75 | 15.55 | 19.78 | 10.82 | 15.2 | 15.77 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53.37 (9.45) | 51.88 (8.79) | 51.85 (8.54) | 53.48 (9.55) | 51.95 (8.74) | 51.68 (8.45) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.18 (3.53) | 23.83 (3.36) | 23.96 (3.28) | 23.85 (3.46) | 24.00 (3.38) | 24.29 (3.40) |

| Daily nutrient intake adjusted for age and total energy, except for total energy | ||||||

| Total energy* | 1673.77 (0.00) | 1673.77 (0.00) | 1673.77 (0.00) | 1673.77 (0.00) | 1673.77 (0.00) | 1673.77 (0.00) |

| Saturated fat | 7.02 (0.02) | 8.99 (0.02) | 10.99 (0.03) | 7.89 (0.02) | 8.62 (0.02) | 9.65 (0.03) |

| Fibre | 9.55 (0.02) | 11.15 (0.02) | 13.51 (0.03) | 8.26 (0.02) | 11.17 (0.02) | 15.26 (0.03) |

| Phosphorus | 852.77 (0.63) | 985.46 (0.66) | 1162.48 (0.91) | 843.66 (0.85) | 975.56 (0.77) | 1161.18 (1.16) |

| Calcium | 310.97 (0.54) | 493.36 (0.57) | 726.90 (0.78) | 335.37 (0.99) | 476.36 (0.90) | 668.24 (1.34) |

| Magnesium | 246.51 (0.21) | 279.27 (0.22) | 329.68 (0.30) | 231.88 (0.23) | 278.50 (0.21) | 347.30 (0.31) |

| Retinol | 146.88 (0.95) | 186.49 (1.00) | 228.98 (1.37) | 163.43 (1.14) | 178.50 (1.03) | 203.98 (1.55) |

| Vitamin E | 10.72 (0.02) | 13.68 (0.03) | 18.63 (0.03) | 9.87 (0.03) | 13.61 (0.03) | 19.39 (0.04) |

| Folate | 254.15 (0.43) | 295.56 (0.45) | 356.16 (0.62) | 227.05 (0.47) | 296.25 (0.43) | 391.14 (0.64) |

| Sodium | 252.92 (0.52) | 355.20 (0.55) | 489.11 (0.75) | 260.13 (0.73) | 345.16 (0.67) | 467.53 (1.00) |

| Potassium | 1479.84 (2.17) | 1826.56 (2.28) | 2293.21 (3.14) | 1360.48 (2.48) | 1808.59 (2.25) | 2440.75 (3.38) |

| Zinc | 10.20 (0.01) | 10.85 (0.01) | 11.84 (0.01) | 10.02 (0.01) | 10.83 (0.01) | 12.02 (0.01) |

| Shanghai Men's Health Study | ||||||

| Married (%) | 96.37 | 97.37 | 97.70 | 96.48 | 97.44 | 97.57 |

| Smokers (%) | 76.18 | 70.32 | 65.45 | 72.67 | 69.22 | 68.34 |

| Alcohol drinkers (%) | 35.66 | 33.56 | 32.74 | 37.01 | 32.52 | 32.88 |

| Tea drinker (%) | 64.96 | 66.92 | 68.45 | 64.3 | 67.47 | 68.3 |

| Ginseng use (%) | 26.27 | 30.99 | 36.7 | 29.24 | 31.99 | 34.14 |

| Ca supplement use (%) | 3.07 | 4.36 | 5.91 | 4.02 | 4.67 | 5.11 |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 3.92 | 6.92 | 10.04 | 6.00 | 7.58 | 8.32 |

| Physically active (%) | 28.03 | 33.68 | 41.16 | 31.45 | 34.69 | 38.28 |

| High school or up (%) | 14.39 | 22.37 | 29.02 | 19.14 | 23.91 | 25.07 |

| Age (years), mean (SD)† | 55.90 (10.27) | 55.28 (9.73) | 55.17 (9.43) | 56.91 (10.58) | 55.56 (9.70) | 54.46 (9.20) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD)† | 23.47 (3.18) | 23.67 (3.09) | 23.90 (3.00) | 23.25 (3.16) | 23.64 (3.04) | 24.02 (3.03) |

| Daily nutrient intake adjusted for age and total energy, except for total energy | ||||||

| Total energy* | 1906.89 (0.00) | 1906.89 (0.00) | 1906.89 (0.00) | 1906.89 (0.00) | 1906.89 (0.00) | 1906.89 (0.00) |

| Saturated fat | 8.16 (0.03) | 9.74 (0.03) | 11.85 (0.03) | 9.59 (0.04) | 9.92 (0.03) | 10.88 (0.03) |

| Fibre | 9.27 (0.03) | 10.72 (0.02) | 13.28 (0.02) | 8.17 (0.03) | 10.32 (0.02) | 14.02 (0.02) |

| Phosphorus | 956.75 (1.17) | 1081.00 (0.93) | 1271.73 (0.87) | 953.79 (1.56) | 1071.31 (1.08) | 1270.89 (1.11) |

| Calcium | 340.34 (1.12) | 512.58 (0.89) | 778.31 (0.83) | 379.76 (1.83) | 518.93 (1.27) | 740.23 (1.30) |

| Magnesium | 271.18 (0.37) | 303.34 (0.30) | 359.14 (0.28) | 258.30 (0.45) | 297.74 (0.31) | 367.15 (0.32) |

| Retinol | 120.06 (1.17) | 154.78 (0.93) | 198.50 (0.87) | 142.50 (1.41) | 156.14 (0.98) | 183.74 (1.00) |

| Vitamin E | 10.72 (0.04) | 13.48 (0.03) | 18.43 (0.03) | 10.13 (0.05) | 13.15 (0.03) | 18.73 (0.04) |

| Folate | 271.83 (0.75) | 319.26 (0.60) | 398.67 (0.56) | 245.92 (0.87) | 308.91 (0.61) | 415.67 (0.62) |

| Sodium | 250.29 (0.92) | 345.02 (0.73) | 489.36 (0.68) | 271.89 (1.28) | 345.24 (0.89) | 470.94 (0.91) |

| Potassium | 1464.92 (3.41) | 1778.86 (2.70) | 2289.70 (2.53) | 1399.54 (4.28) | 1739.67 (2.97) | 2326.91 (3.04) |

| Zinc | 11.54 (0.01) | 12.23 (0.01) | 13.40 (0.01) | 11.38 (0.01) | 12.13 (0.01) | 13.50 (0.01) |

*Adjusted for age only. †SD.

BMI, body mass index.

Statistical analysis

To be consistent with SMHS, we excluded from the analysis 1579 individuals with a history of cancer at baseline from the SWHS. We also excluded 126 individuals in SWHS and 70 in SMHS with an unreasonably high-energy or low-energy intake (<500 or >3500 kcal/day for women; <500 or >4200 kcal/day for men), and eight individuals in SWHS and 14 in SMHS who moved away from Shanghai immediately after the baseline survey. As a result, a total of 73 232 women for SWHS and 61 414 men for SMHS were included in the final analyses.

We estimated the main associations using HR in Cox proportional hazard regression models,37 using age at entry and age at death or age at censor as a timescale.38 To be consistent with previous cohort studies which evaluated the association of Ca and Mg with disease risks,10 22 23 we have adjusted for the following potential confounding factors: age at entry, sex, body mass index, education, marriage status, smoking status, tea drinking, use of ginseng (yes, no), alcohol drinking, use of Ca supplement, use of multivitamin, regular physical activity and intakes of total energy, saturated fatty acid, phosphorus, fibre, retinol, vitamin E, folic acid, sodium, potassium and zinc. Log-transformation was conducted for continuous variables. We have adjusted for age to control for potential birth cohort effect. We have additionally adjusted for postmenopausal hormone use, but the associations did not change.

Determination of low-exposure, medium-exposure and high-exposure categories: since the intake level of Mg in our study population is comparable to that in the studies conducted in Western countries, we have used the US Mg Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for women (320 mg/day), which is very close to the 66th percentile of Mg intake in our study population (321 mg/day), as the upper cut-point. In contrast, very few study participants had a Ca intake level above the current US Daily Reference Intake (DRI) for Ca (1000 mg/day). Thus, we have used 600 mg/day, a previous Ca DRI for Chinese (Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety and Chinese Institute for Preventive Medicine, 1991), as the upper cut-point. We utilised the medians of Mg and Ca for the remaining participants as the lower cut-point. Since the intake levels of Mg and Ca in men were higher than those in women, we have added one cut-point (ie, US RDA for Mg in men (420 mg/day)) for Mg and one cut-point (ie, the current DRI for Ca in Chinese adults (800 mg/day)) for Ca in the analysis for men.

Separate analyses were conducted for SWHS (women) and SMHS (men). The first model was adjusted for age and other confounding factors except for Ca and Mg. In the second model, Ca and Mg were further adjusted to assess whether the association of Mg or Ca was independent of Ca or Mg, respectively. Stratified analyses by medians of the Ca/Mg ratio,10 11 and Ca or Mg intake11 were conducted. In the stratified analyses, the full-adjusted (second) model was used. In addition, we have conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding those who took the Ca supplement or multivitamin. Multiplicative interactions between continuous Mg or Ca and continuous Ca/Mg ratio were tested. Tests for trend across exposure categories were performed by entering the categorical variables as a continuous variable in the model. p Values of <0.05 (two-sided probability) were interpreted as being statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS statistical software (V.9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Selected demographic characteristics and potentially confounding factors were compared by intake levels of Ca and Mg separately for SWHS and SMHS as shown in table 1. Proportions of participants with high educational achievement, female alcohol drinkers, tea drinkers, users of Ca, multivitamin and ginseng supplements, and of those who were physically active and consumed high levels of (energy-adjusted and age-adjusted) saturated fatty acids, fibre, phosphorus, retinol, vitamin E, folate, sodium, potassium, zinc and Mg or Ca increased with increasing intakes of Ca and Mg. The proportion of participants who smoked, male alcohol drinkers and those who were not married decreased with increasing intakes of Ca and Mg.

In the pooled analysis of SMHS and SWHS (Data not shown), we found that sex significantly modified the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg with risk of total mortality (p for interactions <0.01) and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (p for interactions <0.01). Sex also appeared to modify the associations of Ca and Mg with cancer (p for interactions were 0.125 for Mg and 0.280 for Ca, respectively). Thus, separate analyses were conducted for SWHS and SMHS.

Presented in table 2 are the associations of dietary intakes of Ca and Mg with risk of total mortality, mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer in SWHS. After adjusting for potentially confounding factors (model 1) and additionally controlling for Ca or Mg, respectively (model 2), we found that among women, high intake of Mg was significantly associated with 35–50% increased risks of mortality due to cardiovascular diseases, particularly stroke. Furthermore, the Ca/Mg ratio modified the associations between intake of Mg and risk of total mortality (p for interaction, 0.07) and mortality due to coronary heart diseases (p for interaction, 0.02) in model 2. Among those with Ca/Mg ratio ≤1.7, intake of Mg was significantly associated with 24–66% increased risks of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (including stroke and coronary heart disease), and a 120% increased risk of colorectal cancer (p for trend, 0.05). However, among those with a Ca/Mg intake ratio >1.7, intake of Mg was related to a decreased risk of lung cancer (p for trend, 0.01); and intake of Ca was associated with a significantly reduced risk of cancer (p for trend, 0.02), including lung cancer (p for trend, 0.01) and colorectal cancer (p for trend, 0.05), but was related to an increased risk of gastric cancer. We did not present the results for other gastrointestional tract cancers because the sample sizes for mortality due to these gastrointestinal tract cancers are sparse and not reliable. The findings were also not statistically significant. In the sensitivity analyses conducted by excluding those who used Ca or multivitamin supplements, similar results were observed (data not shown).

Table 2.

HRs and 95% CIs for total mortality, and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer by tertiles of calcium and magnesium among women in Shanghai

| Calcium intake (mg/day) magnesium intake (mg/day) | ||||||||||

| <408 | 408–<600 | ≥600 | p for trend | p for interaction | <251 | 251–<320 | ≥320 | p for trend | p for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-years | 349874.66 | 281646.47 | 175026.49 | 335378.89 | 271235.72 | 199933.00 | ||||

| Total mortality | ||||||||||

| Cases | 2019 | 1155 | 632 | 1992 | 1108 | 706 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.15) | 1.06 (0.92 to 1.22) | 0.39 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.16) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 0.27 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.25) | 0.25 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 0.27 | 0.07 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.36) | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.30) | 1.24 (1.02 to 1.51) | 0.02 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.85 to 1.24) | 1.06 (0.81 to 1.39) | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.76 to 1.06) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.13) | 0.31 | ||

| Mortality due to cardiovascular diseases | ||||||||||

| Cases | 649 | 321 | 177 | 625 | 311 | 211 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.22) | 1.08 (0.84 to 1.40) | 0.57 | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.92 to 1.34) | 1.35 (1.03 to 1.77) | 0.04 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.22) | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.40) | 0.57 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.92 to 1.34) | 1.35 (1.03 to 1.77) | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.30) | 1.21 (0.74 to 1.99) | 0.61 | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.93 to 1.48) | 1.53 (1.08 to 2.16) | 0.02 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.35) | 1.07 (0.64 to 1.79) | 0.69 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.39) | 1.14 (0.71 to 1.85) | 0.60 | ||

| Mortality due to coronary heart disease | ||||||||||

| Cases | 284 | 148 | 79 | 290 | 129 | 92 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.31) | 1.01 (0.69 to 1.49) | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.28) | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.78) | 0.46 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.78 to 1.32) | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.54) | 0.84 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.28) | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.79) | 0.46 | 0.02 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.42) | 1.92 (1.00 to 3.70) | 0.27 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.70 to 1.46) | 1.69 (1.02 to 2.80) | 0.07 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.53 to 1.40) | 0.85 (0.41 to 1.76) | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.45) | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.74) | 0.68 | ||

| Mortality due to stroke | ||||||||||

| Cases | 365 | 173 | 98 | 335 | 182 | 119 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.32) | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.60) | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.61) | 1.50 (1.03 to 2.16) | 0.03 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.31) | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.57) | 0.59 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.60) | 1.50 (1.03 to 2.17) | 0.03 | 0.81 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.44) | 0.72 (0.33 to 1.58) | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.30 (0.95 to 1.77) | 1.40 (0.87 to 2.23) | 0.12 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 1.07 (0.65 to 1.77) | 1.35 (0.66 to 2.77) | 0.34 | 1.00 | 1.14 (0.73 to 1.78) | 1.46 (0.75 to 2.85) | 0.26 | ||

| Mortality due to all cancers | ||||||||||

| Cases | 789 | 556 | 271 | 756 | 537 | 323 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.26) | 0.90 (0.72 to 1.12) | 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) | 0.89 (0.70 to 1.14) | 0.42 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.27) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.15) | 0.68 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) | 0.89 (0.70 to 1.14) | 0.42 | 0.78 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.85 to 1.26) | 0.82 (0.54 to 1.25) | 0.73 | 1.00 | 1.19 (0.98 to 1.46) | 1.13 (0.83 to 1.54) | 0.35 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 1.28 (0.93 to 1.77) | 0.99 (0.64 to 1.55) | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.10) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.92) | 0.02 | ||

| Mortality due to lung cancer | ||||||||||

| Cases | 171 | 109 | 50 | 156 | 109 | 65 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.37) | 0.76 (0.47 to 1.24) | 0.34 | 1.00 | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.61) | 1.01 (0.59 to 1.71) | 0.93 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.74 to 1.40) | 0.81 (0.50 to 1.32) | 0.47 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.62) | 1.01 (0.60 to 1.72) | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.13 (0.73 to 1.76) | 1.78 (0.82 to 3.87) | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.45 (0.94 to 2.24) | 1.65 (0.87 to 3.15) | 0.11 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.42 to 1.81) | 0.36 (0.13 to 1.02) | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.13) | 0.30 (0.11 to 0.77) | 0.01 | ||

| Mortality due to colorectal cancer | ||||||||||

| Cases | 109 | 76 | 48 | 96 | 77 | 60 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.60 to 1.30) | 0.76 (0.43 to 1.34) | 0.34 | 1.00 | 1.19 (0.78 to 1.82) | 1.32 (0.70 to 2.51) | 0.39 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.28) | 0.73 (0.41 to 1.29) | 0.28 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.79 to 1.84) | 1.34 (0.70 to 2.54) | 0.37 | 0.19 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.66 to 1.86) | 0.63 (0.19 to 2.08) | 0.84 | 1.00 | 1.92 (1.11 to 3.33) | 2.20 (0.96 to 5.04) | 0.05 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.50 (0.23 to 1.10) | 0.32 (0.11 to 0.94) | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.58 (0.30 to 1.13) | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.53) | 0.25 | ||

| Mortality due to gastric cancer | ||||||||||

| Cases | 108 | 68 | 32 | 114 | 58 | 36 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.77 to 1.72) | 1.05 (0.57 to 1.92) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.28) | 0.77 (0.40 to 1.50) | 0.42 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.78 to 1.75) | 1.09 (0.59 to2.03) | 0.69 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.28) | 0.77 (0.40 to 1.50) | 0.42 | 0.33 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.75 (0.42 to1.35) | 1.34 (0.47 to 3.77) | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.65 (0.37 to1.16) | 0.95 (0.42 to2.15) | 0.72 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 3.41 (1.30 to 8.99) | 3.92 (1.05 to 14.68) | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.10 (0.54 to 2.23) | 0.63 (0.20 to 2.01) | 0.49 | ||

In Model 1, age at entry, sex, body mass index (BMI), education, marriage status, smoking status, tea drinking, use of ginseng, alcohol drinking, use of Ca supplement, use of multivitamin, regular physical activity and intakes of total energy, saturated fatty acid, phosphorus, fibre, retinol, vitamin E, folic acid, sodium, potassium and zinc were adjusted.

In Model 2, Ca and Mg were further adjusted to assess whether the association of Mg or Ca was independent of Ca or Mg, respectively.

*Model 2 was used.

We found that the association patterns with Ca and Mg differed in women (SWHS) and men (SMHS). Because the differential associations could potentially be caused by the use of different sex-specific cut-points, we chose to evaluate first the associations using common cut-points (tables 2 and 3). Thus, table 3 shows the associations between the dietary intakes of Ca and Mg and the risk of total mortality, mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer in SMHS using the same cut-points as those for women in SWHS (table 2). Among men, a high intake of Ca (≥600 mg/day) was related to reduced risks of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and, possibly, cancer, whereas intake of Mg (≥320 mg/day) was possibly related to a reduced risk of death due to coronary heart diseases. In the stratified analysis (model 2), we found that the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg and risks of total mortality and cardiovascular diseases were modified by a Ca/Mg ratio with the p for interactions ranging from 0.01 to 0.07. Among participants with a Ca/Mg intake ratio >1.7, risks of total mortality, and mortality due to coronary heart disease and cancer were significantly reduced with increasing intakes of Ca and Mg. These associations were statistically significant, except for the non-significant inverse association between Mg and cancer. In contrast, among those with a Ca/Mg ratio ≤1.7, intakes of Ca and Mg were not significantly related to risks. The sample size became very sparse in the analysis for subtype cancers due to a shorter follow-up time for SMHS (men) compared to SWHS (women), and none of the associations was significant (data not shown). Analyses limited to those who did not use Ca or multivitamin supplements generated similar results (data not shown).

Table 3.

HR and 95% CIs for total mortality, and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases by tertiles of calcium and magnesium among men in Shanghai

| Calcium intake (mg/day) |

Magnesium intake (mg/day) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <408 | 408–<600 | ≥600 | p for trend | p for interaction | <251 | 251–<320 | ≥320 | p for trend | p for interaction | |

| Person-years | 77215.85 | 112600.73 | 147167.01 | 74633.02 | 109118.9 | 153231.68 | ||||

| Total mortality | ||||||||||

| Cases | 820 | 798 | 800 | 904 | 715 | 799 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.95) | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.70 to 0.93) | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07) | 0.23 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.93) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.07) | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.18) | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.36) | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.21) | 1.23 (0.90 to 1.69) | 0.19 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.70 (0.56 to 0.89) | 0.59 (0.44 to 0.80) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.69 (0.57 to 0.84) | 0.66 (0.50 to 0.88) | 0.01 | ||

| Mortality due to cardiovascular diseases | ||||||||||

| Cases | 305 | 273 | 222 | 323 | 246 | 231 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.14) | 0.72 (0.52 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) | 0.83 (0.58 to1.20) | 0.33 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.16) | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.04) | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.12) | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.21) | 0.35 | 0.07 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.73 to 1.40) | 0.92 (0.49 to 1.70) | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.66) | 1.02 (0.60 to1.73) | 0.91 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.40) | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.29) | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.66 (0.47 to 0.94) | 0.66 (0.39 to 1.11) | 0.12 | ||

| Mortality due to coronary heart disease | ||||||||||

| Cases | 137 | 143 | 115 | 155 | 118 | 122 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.66 to 1.26) | 0.63 (0.40 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.98) | 0.64 (0.38 to 1.08) | 0.10 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.67 to 1.29) | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.06) | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.70 (0.49 to 0.99) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.09) | 0.11 | 0.54 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.16 (0.72 to 1.86) | 1.64 (0.73 to 3.70) | 0.28 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.61 to 1.68) | 0.91 (0.42 to 1.96) | 0.81 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.47 to 1.65) | 0.48 (0.21 to 1.09) | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.48 (0.30 to 0.78) | 0.43 (0.21 to 0.88) | 0.02 | ||

| Mortality due to stroke | ||||||||||

| Cases | 168 | 130 | 107 | 168 | 128 | 109 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.66 to 1.24) | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.26) | 0.35 | 1.00 | 1.08 (0.77 to 1.53) | 1.06 (0.63 to1.76) | 0.84 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.67 to 1.27) | 0.85 (0.54 to 1.33) | 0.47 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.77 to 1.54) | 1.06 (0.63 to 1.77) | 0.83 | 0.06 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.58 to 1.41) | 0.42 (0.15 to 1.19) | 0.21 | 1.00 | 1.32 (0.82 to 2.12) | 1.08 (0.52 to 2.24) | 0.78 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.54 to 1.80) | 1.20 (0.54 to 2.65) | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.56 to 1.54) | 1.02 (0.48 to 2.16) | 0.94 | ||

| Mortality due to all cancers | ||||||||||

| Cases | 320 | 337 | 394 | 335 | 316 | 400 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.70 to 1.05) | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.04) | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.04) | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.28) | 0.74 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.06) | 0.81 (0.61 to 1.07) | 0.14 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.05) | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.29) | 0.75 | 0.97 |

| Ratio≤1.7 | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.20) | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.27) | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.30) | 1.31 (0.80 to 2.13) | 0.26 | ||

| Ratio>1.7 | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.98) | 0.59 (0.37 to 0.93) | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.60 to 1.06) | 0.74 (0.49 to 1.14) | 0.19 | ||

In Model 1, age at entry, sex, body mass index (BMI), education, marriage status, smoking status, tea drinking, use of ginseng, alcohol drinking, use of Ca supplement, use of multivitamin, regular physical activity and intakes of total energy, saturated fatty acid, phosphorus, fibre, retinol, vitamin E, folic acid, sodium, potassium and zinc were adjusted.

In Model 2, Ca and Mg were further adjusted to assess whether the association of Mg or Ca was independent of Ca or Mg, respectively.

*Model 2 was used.

Men had higher intake levels of Ca and Mg than women. In table 4, we repeated the analyses presented in table 3, but added one cut-point (420 mg/day, RDA for US men) for Mg and one cut-point (800 mg/day, the current DRI for Chinese) for Ca. We found that the highest intake of Mg (≥420 mg/day) was significantly associated with increased risks of total mortality and mortality due to cancer. We also found that Ca intake levels between 600 and 800 mg/day, but not higher than 800 mg/day, may be associated with reduced risks of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer. It is worth noting that, at borderline significance, high Ca intake was associated with a reduced risk of death due to colorectal cancer, whereas Mg intake was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer mortality, particularly among those with a Ca/Mg ratio ≤1.7 (p for interaction, 0.05). Analyses limited to those who did not use Ca or multivitamin supplements generated similar results (data not shown).

Table 4.

HR and 95% CIs for total mortality, and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases by calcium and magnesium intake among men in Shanghai

| Calcium intake (mg/day) |

Magnesium intake (mg/day) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <408 | 408–<600 | 600–<800 | ≥800 | p for trend | p for interaction | <251 | 251–<320 | 320–<420 | ≥420 | p for trend | p for interaction | |

| Person-years | 77215.85 | 112600.73 | 90733.06 | 56433.95 | 74633.02 | 109118.90 | 108337.41 | 44894.27 | ||||

| Total mortality | ||||||||||||

| Cases | 820 | 798 | 486 | 314 | 904 | 715 | 564 | 235 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.06) | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.95) | 1.03 (0.80 to 1.31) | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.19) | 1.40 (1.02 to 1.93) | 0.13 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.44) | 0.97 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.20) | 1.41 (1.02 to 1.93) | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.17) | 0.98 (0.68 to 1.40) | 0.70 (0.29 to 1.68) | 0.63 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.23) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.70) | 1.30 (0.79 to 2.13) | 0.14 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.02) | 0.69 (0.50 to 0.95) | 0.97 (0.64 to 1.48) | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.03) | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.13) | 1.39 (0.89 to 2.17) | 0.48 | ||

| Mortality due to cardiovascular diseases | ||||||||||||

| Cases | 305 | 273 | 135 | 87 | 323 | 246 | 168 | 63 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.19) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.97) | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.40) | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.28) | 1.20 (0.69 to 2.08) | 0.95 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.23) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | 1.01 (0.65 to 1.57) | 0.42 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.21) | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.28) | 1.19 (0.69 to 2.07) | 0.94 | 0.07 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.73 to 1.40) | 0.93 (0.50 to 1.74) | 0.80 (0.18 to 3.57) | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.19 (0.84 to 1.70) | 1.02 (0.60 to 1.74) | 1.18 (0.51 to 2.74) | 0.89 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.67 to 1.65) | 0.86 (0.48 to 1.56) | 1.31 (0.61 to 2.82) | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.74 (0.51 to 1.08) | 0.75 (0.43 to 1.31) | 1.05 (0.46 to 2.39) | 0.89 | ||

| Mortality due to coronary heart disease | ||||||||||||

| Cases | 137 | 143 | 70 | 45 | 155 | 118 | 81 | 41 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.31) | 0.63 (0.39 to 1.00) | 0.75 (0.41 to 1.39) | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.54 to 1.14) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.23) | 1.18 (0.54 to 2.56) | 0.88 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.70 to 1.35) | 0.66 (0.41 to 1.06) | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.56) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.15) | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.24) | 1.18 (0.55 to 2.56) | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.72 to 1.85) | 1.69 (0.75 to 3.81) | 1.02 (0.12 to 8.52) | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.62 to 1.77) | 0.92 (0.43 to 2.00) | 1.20 (0.37 to 3.92) | 0.99 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.49 to 1.82) | 0.52 (0.22 to 1.20) | 0.63 (0.21 to 1.86) | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.59 (0.35 to 1.00) | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.20) | 0.96 (0.31 to 2.95) | 0.67 | ||

| Mortality due to stroke | ||||||||||||

| Cases | 168 | 130 | 65 | 42 | 168 | 128 | 87 | 22 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.69 to 1.31) | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.24) | 1.08 (0.59 to 1.98) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.76 to 1.56) | 1.06 (0.63 to 1.78) | 1.08 (0.48 to 2.41) | 0.89 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.70 to 1.35) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.31) | 1.19 (0.64 to 2.21) | 0.97 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 1.09 (0.76 to 1.57) | 1.06 (0.63 to 1.78) | 1.07 (0.48 to 2.40) | 0.89 | 0.06 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.58 to 1.41) | 0.39 (0.13 to 1.20) | 0.65 (0.08 to 5.30) | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.31 (0.81 to 2.13) | 1.08 (0.52 to 2.24) | 1.04 (0.30 to 3.57) | 0.92 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 1.25 (0.66 to 2.34) | 1.57 (0.68 to 3.63) | 2.97 (1.00 to 8.87) | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.54 to 1.60) | 1.02 (0.46 to 2.25) | 1.02 (0.31 to 3.40) | 0.90 | ||

| Mortality due to all cancers | ||||||||||||

| Cases | 320 | 337 | 236 | 158 | 335 | 316 | 273 | 127 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.10) | 0.80 (0.60 to 1.05) | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.38) | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.23) | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.54) | 1.68 (1.03 to 2.74) | 0.07 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.08) | 1.00 (0.68 to 1.46) | 0.72 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.23) | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.54) | 1.68 (1.03 to 2.74) | 0.06 | 0.97 |

| Ratio≤1.7* | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.19) | 0.75 (0.43 to 1.31) | 0.51 (0.15 to 1.79) | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32) | 1.31 (0.80 to 2.15) | 1.33 (0.62 to 2.84) | 0.22 | ||

| Ratio>1.7* | 1.00 | 0.73 (0.50 to 1.08) | 0.65 (0.40 to 1.04) | 0.78 (0.42 to 1.46) | 0.74 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.42) | 1.04 (0.65 to 1.66) | 1.91 (0.97 to 3.76) | 0.18 | ||

In Model 1, age at entry, sex, body mass index (BMI), education, marriage status, smoking status, tea drinking, use of ginseng, alcohol drinking, use of Ca supplement, use of multivitamin, regular physical activity and intakes of total energy, saturated fatty acid, phosphorus, fibre, retinol, vitamin E, folic acid, sodium, potassium and zinc were adjusted.

In Model 2, Ca and Mg were further adjusted to assess whether the association of Mg or Ca was independent of Ca or Mg, respectively.

*Model 2 was used.

We have also conducted stratified analyses to examine whether Ca intake directly interacted with Mg intake in relation to risk of total mortality, mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart diseases and stroke) and cancer. For both men and women, we found that Mg intake was associated with a significantly increased risk of total mortality among those with Ca intake equal to or below the median, but that it was associated with a significantly reduced risk among those with Ca intake above the median (table 5). Among men, although Ca intake was found to be associated with a reduced risk of total mortality when Mg intake was above the median, it was not significantly associated with the risk among those with Mg intake below the median. Similar findings were observed for women, although none of the associations were statistically significant. These findings indicate a pattern for interactions between Ca and Mg. However, Ca–Mg interactions were not statistically significant for total mortality (table 5), and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart diseases and stoke) and cancer and its subtypes in both SWHS and SMHS (data not shown).

Table 5.

HR* and 95% CIs for total mortality by tertiles of calcium and magnesium intake among women and men stratified by the median intake of magnesium and calcium, respectively

| Calcium intake (mg/day) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <480 | 480–<600 | ≥600 | p for trend | p for interaction | |

| SWHS | |||||

| All individuals | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.25) | 0.25 | 0.42 |

| Mg≤284.3† | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.19) | 1.19 (0.93 to1.52) | 0.15 | |

| Mg>284.3† | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.69 to 1.03) | 0.82 (0.64 to 1.05) | 0.19 | |

| SMHS | |||||

| All individuals | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| †Mg≤284.3 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.22) | 0.54 | |

| Mg>284.3† | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.16) | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.03) | 0.03 | |

| Magnesium intake (mg/day) | |||||

| <251 | 251–<320 | ≥320 | p for trend | p for interaction | |

| SWHS | |||||

| All individuals | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 0.27 | 0.42 |

| Ca≤491‡ | 1.00 | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.26) | 1.31 (1.05 to 1.64) | 0.01 | |

| Ca>491‡ | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.64 to 0.98) | 0.70 (0.52 to 0.95) | 0.03 | |

| SMHS | |||||

| All individuals | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.93) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.07) | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| Ca≤491‡ | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.21) | 1.59 (1.15 to 2.20) | 0.06 | |

| Ca>491‡ | 1.00 | 0.70 (0.55 to 0.88) | 0.57 (0.42 to 0.79) | 0.00 | |

*Model 2 was used. Age at entry, sex, body mass index (BMI), education, marriage status, smoking status, tea drinking, use of ginseng, alcohol drinking, use of Ca supplement, use of multivitamin, regular physical activity and intakes of total energy, saturated fatty acid, phosphorus, fibre, retinol, vitamin E, folic acid, sodium, potassium and zinc were adjusted. Ca and Mg were further adjusted to assess whether the association of Mg or Ca was independent of Ca or Mg, respectively.

†Mg, magnesium intake.

‡Ca, calcium intake.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

In contrast to studies conducted in the USA with a high Ca/Mg ratio which generally found inverse associations, we found in Chinese populations with a low Ca/Mg intake ratio that high intake of Mg (≥320 mg/day for women and ≥420 mg/day for men) was overall related to an increased risk of total mortality among both men and women, mortality due to cardiovascular diseases among women and mortality due to cancer among men after mutually adjusting for intake of Ca and other confounding factors. Furthermore, we found that the Ca/Mg ratio significantly modified the associations between intakes of Ca and Mg with risks of total mortality and coronary heart diseases and possibly cancer, whereas we did not identify any significant interactions between Ca and Mg in relation to these outcomes. Among those with Ca/Mg ratios above the median, intakes of Ca and Mg were associated with reduced risks of total mortality, and mortality due to coronary heart diseases for both men and women, and cancer for men, whereas Mg intake was associated with a decreased risk of cancer mortality for women. Conversely, among those with a Ca/Mg ratio equal to or below the median, intake of Mg was associated with increased risks of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases for men and women as well as colorectal cancer for women and possibly gastric cancer for men.

Hypothesis and overall biological mechanism

Ionised Ca has a central role in cellular signalling,39 controlling numerous cellular processes,40 while ionised Mg is essential in over 300 biological activities.8 Ca and Mg have similar chemical properties and share the same homeostatic regulating system including gut absorption and kidney reabsorption to maintain a normal balance of Ca and Mg.1 Furthermore, the changes in blood or colon lumen concentrations for Ca2+ and Mg2+ are monitored by the same receptor, the CaSR.1 Once the Ca or Mg concentration is high, CaSR could respond to it even if the concentration of Mg or Ca, respectively, is low, resulting in the simultaneous depression of the (re)absorption process for both Ca and Mg.2 4 Thus, in clinics, hypomagnesaemia is commonly linked to secondary hypocalciuria.41 Previous studies also showed that changes in the dietary Ca/Mg balance affected systemic inflammation responses in animal models.3 14 In addition to inflammation, Mg2+ and Ca2+ potentially antagonise each other in many other physiological activities, such as oxidative stress42 and insulin resistance,18 43 DNA repair, cell differentiation and proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis,3 6 44 which may also be involved in the development of cancer, cardiovascular diseases and many other diseases. As we mentioned in the introduction, if the total absorbed number of Ca and Mg ions is relatively constant, the absorbed numbers of Ca and Mg are dependent on the Ca/Mg ratio in the gut. Therefore, the Ca/Mg ratio to which gut epithelial cells are directly exposed may modify the absorption of Ca and Mg and other activities in the gut.10 11

Comparison with previous studies

Possible explanations on findings with colorectal cancer

In 2007, we reported from a study conducted in the USA that only Mg intake from a dietary source was related to a non-significantly reduced risk of colorectal adenoma, whereas total Mg intake from both dietary and supplemental sources was associated with a significantly reduced risk.10 The inverse associations with both the total intakes of Ca or Mg may primarily appear among those whose Ca/Mg ratio was below 2.78.10 Similar to our finding, in a very recent case–control study conducted in the Netherlands, Wark et al45 found that dietary Mg only (not including Mg from supplementation) was marginally significantly related to a reduced risk of colorectal adenoma. In our 2007 report, we found that p for interaction between total Mg and total Ca/Mg ratio was 0.1010 whereas p for interaction was 0.65 between dietary Mg and the dietary Ca/Mg ratio. Interestingly, the study conducted by Wark et al45 also did not find a significant interaction between dietary Mg and the dietary Ca/Mg ratio (p for interaction=0.86). It is possible that a misclassification in the analyses owing to only using Ca and Mg from a dietary source may bias the result to the null. In a recent paper based on the analysis of a large clinical trial, Ca supplementation reduced the risk of colorectal adenoma recurrence only among those with a baseline dietary Ca/Mg ratio less than or equal to 2.63.10 11 Moreover, the effect of Ca treatment did not significantly differ by baseline intake of Ca or Mg alone.11 46 Zhang et al47 found in the Nurses’ Health Study that the interaction between total Ca and Mg intakes (p for interaction, 0.17) was also not statistically significant in relation to the risk of colorectal cancer incidence.

Overall interpretations for findings on diseases other than colorectal cancer

Consistent with these published findings on colorectal neoplasia, we found in the current study that the associations between Ca or Mg with total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer were not significantly modified by Mg or Ca, respectively, but that many of these associations were significantly modified by the Ca/Mg ratio. In a recent study, we found that a high serum Ca/Mg ratio was statistically associated with an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer even after adjusting for both serum Ca and Mg,12 indicating that the balance between Ca and Mg may affect the risk or pathogenesis of diseases other than colorectal cancer or adenoma. In addition to competition for absorption, a previous study found that Mg supplementation increased urinary Ca excretion if the intake of Ca was <800 mg/day,29 suggesting that Mg may suppress Ca reabsorption when the Ca/Mg intake ratio is very low. It is possible that the Ca and Mg statuses in the body and specific organs or tissues could be indirectly modified by the dietary Ca/Mg ratio through affecting both the absorption and reabsorption processes.29 48 As a result, it is not surprising that we found that the dietary Ca/Mg ratio also modified the effects of Ca and Mg on risk of diseases occurring in organs which do not directly expose to dietary Ca and Mg. However, it is conceivable, through the homeostasis regulation by (re)absorption, that the Ca/Mg ratio in the gut differs from that in the circulation and other systems. Thus, the modification effects of the dietary Ca/Mg ratio may become weaker on diseases occurring in organs other than the digestive tract. For example, among women with a Ca/Mg ratio ≤1.7, high intake of Mg was associated with a 24% increased risk of total mortality and 66% increased risk of coronary heart disease death compared with 120% increased risk for colorectal cancer death. Among women with a Ca/Mg ratio >1.7, intake of Ca has the strongest inverse association with gastrointestinal cancer.

Comparison with studies on the association of Mg with CVD

The associations between Mg intake with risk of stroke49 50 and coronary heart disease49 51incidence and death have not been entirely consistent in previous prospective studies. Two meta-analyses found that Mg intake was related to a significantly reduced risk of stroke.49 50 However, the inverse association was weak and only existed with ischaemic stroke, but not haemorrhagic stroke.50 Also, a previous meta-analysis found that Mg intake was non-significantly inversely associated with coronary heart disease.49 No study has examined the possible effect of modifications by the Ca/Mg ratio. A very recent report from the JACC study conducted in Japan, a population also with a low Ca/Mg ratio, found that dietary intake of Mg was significantly related to reduced risks of mortality due to haemorrhagic stroke in men and cardiovascular diseases in women.51 However, after adjusting for intakes of Ca and potassium, all these inverse associations not only disappeared but also became positive associations, which were significant for total stroke in women with an HR (95% CI) of 1.81 (1.12 to 2.94) for the highest quintile intake versus the lowest (p for trend, 0.015) and of borderline significance for ischaemic stroke in women (p for trend, 0.081). Thus, these findings from the study conducted in a Japanese population are consistent with what we found in Chinese populations. Furthermore, previous cohort studies have relatively consistently found that a high dietary intake of Mg was associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome15 and type II diabetes16–18 and insulin resistance13 in Western populations. However, clinical trials using different high doses of Mg supplementations led to inconsistent results on glycaemic control among diabetes patients.52 The null effect in many of these trials could be due to a high dose of Mg supplementation resulting in a very low Ca/Mg ratio (<1.7). Future studies are needed to confirm this possibility.

Comparison with studies on the association of Ca with CVD

Similar to Mg, previous cohort studies have also provided inconsistent results on the associations between Ca intake and the supplemental use of Ca and risk of cardiovascular diseases.53 54 A meta-analysis of these studies showed a non-significant result with either coronary heart disease or stroke.53 No study has examined whether the Ca/Mg ratio modifies the association between Ca intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease incidence or death. A recent study conducted among a population with a high intake level of Mg found the intake of Ca, but not Mg, to be associated with a reduced risk of total mortality and, very likely, mortality due to cardiovascular diseases.54 In a joint analysis, intake of Ca was found to be significantly related to a reduced risk of total mortality only when the intake of Mg was under 480 mg/day. It is very important to mention that this study was conducted in a population located in the northern latitude where sunlight is very limited for vitamin D synthesis from autumn to spring.55 Furthermore, the investigators excluded those who took dietary supplements including vitamin D supplements from the study. As a result, the average intake level of vitamin D was as low as 6.5 µg/day. Thus, it is expected in a population at high risk of vitamin D deficiency that Ca intake would be related to a reduced risk of total mortality even at a very high level, particularly among those with a relatively low intake of Mg (no absorption competition from Mg). In contrast, although still controversial, recent findings from a reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative study and meta-analysis of secondary clinical trials data conducted among populations with a high Ca/Mg ratio suggest that high Ca supplementation with or without vitamin D may modestly increase the risk of cardiovascular events, especially myocardial infarction.56 57 Also, we found that Ca intake levels between 600 and 800 mg/day, but not higher than 800 mg/day, may be associated with reduced risks of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer. Our finding is supported by the results from both the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. In these two studies, the furthest reduction in risk of colorectal cancer associated with intake of Ca was achieved by intakes of 700–800 mg/day, but no additional reduction in risk was observed at higher intakes of Ca.58

In an additional analysis in the JACC, the reduction in risk of mortality due to coronary heart disease was only significant among those with high intakes of both Ca and Mg compared to those with low intakes of both.51 This finding indicates that high Ca plus high Mg, not high Ca or Mg alone, was significantly associated with a reduced risk. The Ca/Mg ratio for people who had both high Ca and high Mg intakes or those with both low Ca and low Mg intakes is in the middle range (ie, smaller than those with a high Ca and low Mg intake, but greater than those with a low Ca and high Mg intake). Among those with a Ca/Mg ratio in the middle, high intakes of Ca and Mg had a reduced risk compared with those with low intakes of Ca and Mg. Thus, this joint association between Ca with Mg found in the JACC is in general consistent with the modifying effects by the Ca/Mg ratio observed in the current study. We have also replicated this joint analysis in the current study and found a similar finding among men, but not women. Also, in the current study, we found many significant interactions between the Ca/Mg ratio with Ca or Mg, but zero significant interactions between Ca and Mg intakes in relation to disease mortality, suggesting that the Ca/Mg ratio has a stronger modifying effect than Ca or Mg alone. The fact is also consistent with that predicted mathematically.

Possible interpretations on the sex modification

In the current study of a population with a low-dietary Ca/Mg ratio, we found that Mg intake (≥320 mg/day) among women and a higher dose among men (ie, Mg intake ≥420 mg/day) was related to an increased risk of total mortality. Furthermore, we found that the associations between the intakes of Ca and Mg and the risk of total mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases differed significantly by sex. These findings are biologically meaningful because of the effects of oestrogen on Mg and Ca metabolism.59 For example, oestrogen shifted Mg from circulation (serum) into cells, and thus, lower Mg intake was required for young women than young men to keep a positive Mg balance.59 Seelig et al59 proposed that the increase of the Ca/Mg intake ratio from 2.0 in 1920s to over 3.0 in the USA contributed to a sharp rise in incidence of cardiovascular diseases in men, but not women, and that this ratio is continuously rising in recent years.60 Some previous cohort studies conducted in populations with a high Ca/Mg ratio have also provided some support. For example, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study found an inverse association between Mg intake and serum Mg and risk of coronary heart disease in men, but not in women, and that p for interaction was 0.07 for serum Mg with sex.61 Although a meta-analysis association for cohort studies was not significant, all studies conducted among men had an RR/HR under 1.00 for the association between Mg intake and the risk of coronary heart disease, whereas only two studies conducted among women had an RR/HR above 1.00.49 Mg was weakly but significantly associated with a reduced risk of stroke in a very recent meta-analysis.50 However, the Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study found an inverse association between Mg intake and the risk of stroke, particularly among men with hypertension, whereas Mg intake was not related to risk among the Nurses’ Health Study.49 Further studies are necessary to understand the potential sex modifications.

Interesting preliminary observations on gastric cancer and stroke

One interesting, but preliminary, observation in the current study is that Mg intake may be associated with an increased risk of deaths due to stroke and gastric cancer (among men). Previous studies found that, compared with the world average, the Chinese population had a much lower incidence and death rate of coronary diseases, but a much higher incidence and death rate of stroke62; and that China is also among the regions with the highest rate of gastric cancer, particularly among men.63 It is possible that the low Ca/Mg ratio in Chinese populations may partially contribute to the higher risks. However, further studies are necessary to explore this possibility.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths include a population-based prospective design, large sample size and high rates for baseline participation and follow-up, which minimise potential differential recall bias or selection bias. The current study has been conducted in a population with a low Ca/Mg intake ratio. Thus, caution should be used to generalise our findings to populations with a high Ca/Mg ratio before further studies are conducted to examine whether Ca/Mg ratio or Mg and Ca modifies the associations of Ca and Mg intakes with the risk of non-gastrointestinal diseases10 11 in populations with a high Ca/Mg ratio. We have adjusted for many potential confounding factors, including Ca supplement and multivitamin use, and also found similar results in sensitivity analysis by excluding those who used Ca or multivitamin supplements. However, the Ca and Mg contents of drinking water could not be calculated. This may lead to non-differential misclassification of Ca and Mg intake, which usually biases associations towards the null. Finally, sample size became smaller in the analyses by cancer subtype, particularly among men. Thus, some of the null associations in subtype analysis could be due to a small sample.

Conclusion and clinical and public health implications

In the current study conducted in populations with lower Ca/Mg ratios, we found that when the Ca/Mg ratio was above 1.7, high intake of Ca was related to a reduced risk of colorectal cancer death and the reduction in risk was the strongest among all the associations between Ca and disease mortality. Conversely, among those with a Ca/Mg ratio less than or equal to 1.7, high intake of Mg was related to a significantly increased risk of mortality due to colorectal cancer in women. Collectively, the findings from the current study, as well as some previous studies conducted in populations with high Ca/Mg ratios,10 11 indicate that a Ca/Mg ratio between 1.70 and 2.63 may be required for high intakes of Ca and Mg to be protective against colorectal cancer.

In addition to colorectal cancer, the potential modifications by the dietary Ca/Mg ratio and sex may provide possible explanations for the inconsistencies on the associations between intake of Ca and Mg with risk of coronary heart diseases,49 53 54 stroke49 50 53 and total cancer54 64 in previous studies.

Future studies are necessary to confirm our finding of modifying effects of the Ca/Mg ratio and to define the optimal Ca/Mg intake ratio range. Our findings, if confirmed, will have a very important public health significance, including selecting optimal doses in the intervention trials and in the prevention strategy development for many common diseases. Furthermore, the Ca/Mg ratio should be taken into account when the new RDA or DRI levels of Ca and Mg are developed. For example, lower RDA or DRI levels of Mg for men and women may be required for Chinese populations because they have a low Ca/Mg intake ratio.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and staff for the SWHS and SMHS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: QD developed the hypothesis and drafted the manuscript, and also had primary responsibility for the final content; WZ, XOS and WHC designed, directed and obtained funding for the parent studies, and contributed to the revisions and data interpretation of the paper; XD and HC contributed to the data analysis, manuscript revisions and data interpretation; GY, YTG, YBX and HL contributed to the study design, data collection of the parent studies, manuscript revisions and data interpretation; MJS and BJ contributed to the manuscript revisions and data interpretation of the paper.

Funding:This study was supported by USPHS grant R37CA70867 and R01CA082729 from the National Institutes of Health. Part of DQ's effort on the study has been supported by R37CA70867, R01CA082729, R01 AT004660 and R01 CA149633 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services and AICR #08A074-REV from the American Institute for Cancer Research.

Competing interests: The funding sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, statistical analysis and result interpretation, as well as in the writing of the report and the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Study approval: Institutional review board.

Ethics approval: Vanderbilt University IRB and Shanghai Cancer Institute IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol Rev 2001;81:239–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardwick LL, Jones MR, Brautbar N, et al. Magnesium absorption: mechanisms and the influence of vitamin D, calcium and phosphate. J Nutr 1991;121:13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussiere FI, Gueux E, Rock E, et al. Protective effect of calcium deficiency on the inflammatory response in magnesium-deficient rats. Eur J Nutr 2002;41:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman DA, Fordtran JS, Brinkley LJ, et al. Jejunal and ileal adaptation to alterations in dietary calcium: changes in calcium and magnesium absorption and pathogenetic role of parathyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Invest 1981;67:1599–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen FH, Milne DB, Gallagher S, et al. Moderate magnesium deprivation results in calcium retention and altered potassium and phosphorus excretion by postmenopausal women. Magnes Res 2007;20:19–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iseri LT, French JH. Magnesium: nature's physiologic calcium blocker. Am Heart J 1984;108:188–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SEELIG MS. Increased need for magnesium with the use of combined oestrogen and calcium for osteoporosis treatment. Magnes Res 1990;3:197–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flatman PW. Mechanisms of magnesium transport. Annu Rev Physiol 1991;53:259–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Epithelial Ca2+ and Mg2+ channels in health and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Q, Shrubsole MJ, Ness RM, et al. The relation of magnesium and calcium intakes and a genetic polymorphism in the magnesium transporter to colorectal neoplasia risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:743–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Q, Sandler RS, Barry EL, et al. Calcium, magnesium, and colorectal adenoma recurrence: results from a randomized trial. Epidemiology 2012;23:504–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai Q, Motley SS, Smith JA, Jr, et al. Blood magnesium, and the interaction with calcium, on the risk of high-grade prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e18237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manolio TA, Savage PJ, Burke GL, et al. Correlates of fasting insulin levels in young adults: the CARDIA study. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:571–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler D. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory cardiovascular disorder. Curr Mol Med 2005;5:309–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He K, Liu K, Daviglus ML, et al. Magnesium intake and incidence of metabolic syndrome among young adults. Circulation 2006;113:1675–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet and risk of clinical diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:1018–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Ridaura R, Willett WC, Rimm EB, et al. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 2004;27:134–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. Dietary magnesium intake in relation to plasma insulin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2004;27:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh RB. Effect of dietary magnesium supplementation in the prevention of coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death. Magnes Trace Elem 1990;9:143–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Delaimy WK, Rimm EB, Willett WC, et al. Magnesium intake and risk of coronary heart disease among men. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong JY, Xun P, He K, et al. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2116–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Magnesium intake in relation to risk of colorectal cancer in women. JAMA 2005;293:86–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folsom AR, Hong CP. Magnesium intake and reduced risk of colon cancer in a prospective study of women. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:232–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Brandt PA, Smits KM, Goldbohm RA, et al. Magnesium intake and colorectal cancer risk in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 2007;96:510–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai H, Shu XO, Hebert JR, et al. Variation in nutrient intakes among women in Shanghai, China. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:1604–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai H, Yang G, Xiang YB, et al. Sources of variation in nutrient intakes among men in Shanghai, China. Public Health Nutr 2005;8:1293–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ervin RB, Wang CY, Wright JD, et al. Dietary intake of selected minerals for the United States population: 1999–2000. Adv Data 2004;27:1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SEELIG MS. The requirement of magnesium by the normal adult. Summary and analysis of published data. Am J Clin Nutr 1964;14:242–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer H, Fuller H, Norris C, et al. Effect of magnesium on the intestinal absorption of calcium in man. J Am Coll Nutr 1994;13:485–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng W, Chow WH, Yang G, et al. The Shanghai Women's Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:1123–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai H, Shu XO, Gao YT, et al. A prospective study of dietary patterns and mortality in Chinese women. Epidemiology 2007;18:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai Q, Shu XO, Li H, et al. Is green tea drinking associated with a later onset of breast cancer? Ann Epidemiol 2010;20:74–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Shu XO, Xiang YB, et al. Cruciferous vegetable consumption is associated with a reduced risk of total and cardiovascular disease mortality. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:240–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao C, Yang G, Hu J, et al. Validation of cause-of-death statistics in urban China. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:642–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villegas R, Yang G, Liu D, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food-frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai men's health study. Br J Nutr 2007;97:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shu XO, Yang G, Jin F, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai Women's Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;58:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis. Regression modeling of time to even data. New York: Wiley, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P. Calcium—a life and death signal. Nature 1998;395:645–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bootman MD, Berridge MJ. The elemental principles of calcium signaling. Cell 1995;83:675–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlingmann KP, Konrad M, Seyberth HW. Genetics of hereditary disorders of magnesium homeostasis. Pediatr Nephrol 2004;19:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hans CP, Chaudhary DP, Bansal DD. Effect of magnesium supplementation on oxidative stress in alloxanic diabetic rats. Magnes Res 2003;16:13–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paolisso G, Sgambato S, Gambardella A, et al. Daily magnesium supplements improve glucose handling in elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:1161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolf FI, Maier J, Nasulewicz A, et al. Magnesium and neoplasia: from carcinogenesis to tumor growth and progression or treatment. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007;458:24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wark PA, Lau R, Norat T, et al. Magnesium intake and colorectal tumor risk: a case-control study and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallace K, Baron JA, Cole BF, et al. Effect of calcium supplementation on the risk of large bowel polyps. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:921–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Giovannucci EL, Wu K, et al. Magnesium intake, plasma C-peptide, and colorectal cancer incidence in US women: a 28-year follow-up study. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1335–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahota O, Mundey MK, San P, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency and the blunted PTH response in established osteoporosis: the role of magnesium deficiency. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:1013–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Y, Manson JE, Cook NR, et al. Dietary magnesium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease among women. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1135–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Dietary magnesium intake and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:362–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang W, Iso H, Ohira T, et al. Associations of dietary magnesium intake with mortality from cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. Atherosclerosis 2012;221:587–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, et al. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med 2006;23:1050–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Manson JE, Sesso HD. Calcium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies and randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2012;12:105–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaluza J, Orsini N, Levitan EB, et al. Dietary calcium and magnesium intake and mortality: a prospective study of men. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:801–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steingrimsdottir L, Gunnarsson O, Indridason OS, et al. Relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels, vitamin D sufficiency, and calcium intake. JAMA 2005;294:2336–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, et al. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giovannucci E. Diet, body weight, and colorectal cancer: a summary of the epidemiologic evidence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:173–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seelig MS, Altura BM, Altura BT. Benefits and risks of sex hormone replacement in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:482S–96S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosanoff A. Rising Ca:Mg intake ratio from food in USA Adults: a concern? Magnes Res 2010;23:S181–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liao F, Folsom AR, Brancati FL. Is low magnesium concentration a risk factor for coronary heart disease? The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J 1998;136:480–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Z, Yao C, Zhao D, et al. Sino-MONICA project: a collaborative study on trends and determinants in cardiovascular diseases in China, Part i: morbidity and mortality monitoring. Circulation 2001;103:462–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parkin DM, Whelen SL, Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence in five continents. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1997;7 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li K, Kaaks R, Linseisen J, et al. Dietary calcium and magnesium intake in relation to cancer incidence and mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg). Cancer Causes Control 2011;22:1375–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.