Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between the route to diagnosis, patient characteristics, treatment intent and 1 -year survival among patients with oesophagogastric (O-G) cancer.

Setting

Cohort study in 142 English NHS trusts and 30 cancer networks.

Participants

Patients diagnosed with O-G cancer between October 2007 and June 2009.

Design

Prospective cohort study. Route to diagnosis defined as general practitioner (GP) referral—urgent (suspected cancer) or non-urgent, hospital consultant referral, or after an emergency admission. Logistic regression was used to estimate associations and adjust for differences in casemix.

Main outcome measures

Proportion of patients diagnosed by route of diagnosis; proportion of patients selected for curative treatment; 1-year survival.

Results

Among 14 102 cancer patients, 66.3% were diagnosed after a GP referral, 16.4% after an emergency admission and 17.4% after a hospital consultant referral. Of the 9351 GP referrals, 68.8% were urgent. Compared to urgent GP referrals, a markedly lower proportion of patients diagnosed after emergency admission had a curative treatment plan (36% vs 16%; adjusted OR=0.62, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.74) and a lower proportion survived 1 year (43% vs 27%; OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.89). Urgency of GP referral did not affect treatment intent or survival. Routes to diagnosis varied across cancer networks, with the adjusted proportion of patients diagnosed after emergency admission ranging from 8.7 to 32.3%.

Conclusions

Outcomes for cancer patients are worse if diagnosed after emergency admission. Primary care and hospital services should work together to reduce rates of diagnosis after emergency admission and the variation across cancer networks.

Keywords: Primary Care

Article summary.

Article focus

To investigate the relationship between the route to diagnosis, patient characteristics, treatment intent and 1-year survival.

To examine whether the routes to diagnosis varied between regional cancer networks.

Key messages

Two-thirds of patients diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer were referred by their general practitioner (GP), of which around two-thirds were referred urgently. Patients referred as an urgent (2-week wait) referral by their GP did not have better survival rates than non-urgent GP referrals.

One in six patients was diagnosed after an emergency admission, and these patients were less likely to have a curative treatment plan compared to urgent GP referrals. One-year survival was also worse.

There was significant variation between cancer networks in the rates of emergency admission, which persisted after adjusting for patient factors.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study uses data from the large, prospective sample of patients diagnosed in almost all English NHS trusts. One-year survival was known for all patients.

Limitations stem from the study capturing only 62% of all patients eligible for the study and from the exclusion of patients owing to missing data on route to diagnosis and treatment intent.

Introduction

Oesophagogastric (O-G) cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in the UK resulting in approximately 12 500 deaths/year.1 The majority of patients are diagnosed with advanced disease and only 20–30% are suitable for curative treatment.2 3 Consequently, the prognosis is often poor, with a 5-year relative survival being approximately 15%.4

An objective of the UK Cancer Reform Strategy has been to increase the proportion of patients diagnosed with early cancer.5 Meeting this objective represents a considerable challenge for O-G cancer services and general practitioners (GP). Many of the symptoms and signs of O-G cancer are non-specific and are present in large numbers of individuals without cancer.6 For example, uncomplicated dyspepsia constitutes 3–4% of a GP's workload,7 8 but an average GP will see only four or five O-G cancer patients per year.6 Guidelines recommend that GPs refer urgently to a specialist team only if patients present with ‘alarm symptoms’ (eg, weight loss, vomiting or dysphagia) or have persistent dyspepsia and are over 55 years.9–11 However, these alarm symptoms are typically associated with advanced disease.12 13

Across all cancer types, the number of patients diagnosed after an urgent GP referral increased from 80 000 in 2007 to 98 000 in 2009.14 But, for O-G cancer patients, information about patients’ route to diagnosis and how this affects outcomes is limited.15 Figures from routine data suggest that a substantial minority of O-G cancer patients are diagnosed following an emergency presentation and these patients have worse survival.16–18 One-year relative survival among all patients with oesophageal cancer was 40%, but it was only 18% for those diagnosed after an emergency presentation; among patients with stomach cancer, the corresponding survival figures were 41% and 23%.18 However, evidence about these relationships is sparse, and there is a need to understand how route to diagnosis contributes with patient characteristics and treatment decisions to influence survival.

This study used a prospectively collected national clinical dataset of patients with O-G cancer in England to investigate the relationship between the route to diagnosis, patient characteristics, treatment intent and 1-year survival. We also examined whether the routes to diagnosis varied between regional cancer networks.

Materials and methods

Data were collected prospectively by English NHS trusts as part of the national O-G cancer audit. All adult patients diagnosed in England with invasive, epithelial cancer of the oesophagus or stomach between 1 October 2007 and 30 June 2009 were eligible for inclusion. The audit method and dataset have been published elsewhere.3 19

The study captured route to diagnosis by adopting the ‘source of referral’ and ‘cancer referral priority’ data items from the National Cancer Dataset.20 Source of referral to the cancer specialist/team differentiated between: referral from a GP (non-emergency and to outpatient clinics), referral after an emergency admission (via accident and emergency, medical admissions unit, etc) and an ‘other hospital referral’ (patients referred by a hospital consultant from a non-emergency setting). Patients referred by GPs under the urgent ‘2-week wait’ (2WW) referral system were classified as ‘urgent (for suspected cancer)’. All other GP referrals to the cancer team via outpatients were grouped as ‘non-urgent’. Information was also collected on the patient's age at diagnosis, sex, social deprivation, tumour site and TNM stage V.6 (tumour node metastasis),21 number of comorbidities, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group (ECOG) functional performance and treatment intent. Date of death was obtained from the Office for National Statistics death certificate register, which gave full follow-up for a minimum of 380 days from the date of diagnosis. Tumour site was categorised as oesophageal (including Siewert 1–3 junctional tumours) or stomach. Treatment intent (curative or palliative) reflected the decision of the multidisciplinary team meeting after pretreatment staging was completed. Social deprivation was measured using the UK Index of Multiple Deprivation22 with patients being grouped into quintiles from the least deprived (= 1) to most deprived (= 5).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportion of patients diagnosed via the different routes for all England and the 30 cancer networks that existed on 1 October 2007. Patients were grouped into networks by their NHS trust of diagnosis. The relationship between two variables was examined using the χ2 test. The association between the route to diagnosis and the proportion of patients having a curative treatment plan and 1-year survival was examined using logistic regression to control for the influence of age at diagnosis, sex, regional deprivation, tumour site, pretreatment stage, comorbidities and performance status.

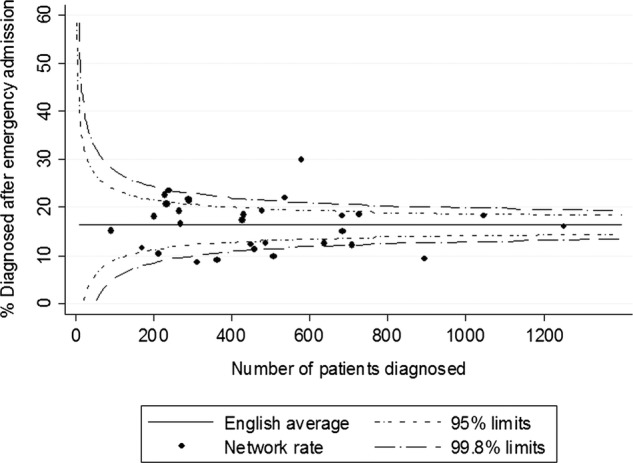

Multinomial logistic regression was used to adjust the proportion of patients diagnosed via each route in each cancer network for patient characteristics.23 Funnel plots were used to test whether network rates differed significantly from the overall English rate.24 These graphs show the network rates together with the English rate and two sets of control limits that indicate the ranges within which 95 or 99.8% of the network rates would be expected to fall if differences from the English rate arose from random variation alone.

The analysis was performed in STATA V.10. All p values are two-sided and those lower than 0.05 were considered to show a statistically significant result. Two variables used in the regression models, performance status and pretreatment stage, were known for 72% and 61% of the patients, respectively. Missing data values for these two variables were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations.25 The imputation model included age at diagnosis, sex, tumour site, deprivation, number of comorbidities, referral source and 1-year survival. Twenty-five imputations were created. Missing values were assumed to be ‘missing at random’ (see online supplementary material for details of missing and imputed values).

Results

Information was collected on 16 264 patients from 152 English NHS trusts. Ten NHS trusts were excluded (1196 patients) because the route to diagnosis was entered for less than half of their patients. Six of these trusts had this information on less than 10% of their patients. Other patient records that lacked route to diagnosis (n=956) or age at diagnosis (n=10) were also excluded. This left 14 102 patients in the analysis. Their median age was 73 years, two-thirds were male, and 69% had an oesophageal tumour. Patients with stomach tumours were slightly older on average (mean 73.6 vs 70.4 years, p<0.001) and fewer were aged less than 55 years (7.1% vs 9.3%, p<0.001). Among patients with known pretreatment stage, 44% had stage 4 (metastatic) disease.

Patterns of route to diagnosis

Overall, 66.3% of patients were referred by their GP, 16.4% were referred following an emergency hospital admission and 17.3% were referred from another hospital consultant. The proportion of GP referrals was lower among patients with stomach tumours compared to oesophageal tumours, which reflected a greater proportion of stomach cancers being diagnosed after an emergency admission (table 1). Diagnosis after emergency admission was least common among patients aged 55–64 years but increased among older and younger patients. This route to diagnosis was also more common among patients as their performance status got worse.

Table 1.

Proportions of patients with oesophagogastric cancer by the route to diagnosis

| Patients | (%) | Route to diagnosis (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner referral | Emergency admission | Other hospital | p Value | |||

| All patients | 14102 | 66 | 16 | 17 | ||

| Tumour | ||||||

| Oesophagus | 9755 | (69) | 71 | 13 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Stomach | 4347 | (31) | 56 | 24 | 19 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 4631 | (33) | 66 | 18 | 17 | =0.02 |

| Male | 9471 | (67) | 67 | 16 | 18 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Under 55 | 1215 | (9) | 66 | 14 | 20 | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 2567 | (18) | 72 | 11 | 17 | |

| 65–74 | 4093 | (29) | 69 | 13 | 19 | |

| 75–84 | 4465 | (32) | 65 | 18 | 17 | |

| 85 and over | 1762 | (12) | 58 | 30 | 12 | |

| Index of multiple deprivation | ||||||

| 1 (least) | 2498 | (18) | 70 | 14 | 16 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 2814 | (20) | 68 | 16 | 16 | |

| 3 | 2969 | (21) | 68 | 15 | 17 | |

| 4 | 2879 | (20) | 64 | 19 | 17 | |

| 5 (most) | 2942 | (21) | 62 | 18 | 20 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| 0 | 7870 | (56) | 70 | 14 | 16 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 3829 | (27) | 65 | 17 | 18 | |

| 2 | 1676 | (12) | 59 | 21 | 19 | |

| 3 or more | 727 | (5) | 54 | 25 | 21 | |

| Performance status | ||||||

| 0 | 3541 | (25) | 74 | 8 | 19 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2838 | (20) | 70 | 12 | 18 | |

| 2 | 1926 | (14) | 63 | 20 | 18 | |

| 3 or 4 | 1812 | (13) | 48 | 36 | 16 | |

| Missing | 3985 | (28) | 67 | 16 | 16 | |

| Pretreatment stage | ||||||

| 1 or 2 | 2543 | (18) | 64 | 13 | 22 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 2296 | (16) | 74 | 11 | 16 | |

| 4 | 3804 | (27) | 67 | 20 | 14 | |

| Unknown/missing | 5459 | (39) | 64 | 18 | 18 | |

In terms of the overall routes to diagnosis, the proportions of patients with oesophageal and stomach tumours who were referred as urgent (2WW) were 50.3% and 35.3%, respectively. In relation to GP referrals only, 71.1% of oesophageal cancer patients and 62.6% of gastric cancer patients were labelled as urgent (2WW). These proportions were lower for patients aged below the guideline threshold. For oesophageal tumours, 64.4% of patients aged less than 55 years were referred urgently (2WW) by GPs compared to 71.8% for older patients. For stomach tumours, the proportions were 50.6% and 63.5%, respectively.

Association between route to diagnosis, treatment intent and 1-year survival

There was a strong association between the route to diagnosis and the likelihood of a patient having a curative treatment plan (table 2). The differences in the unadjusted proportions partly reflected the characteristics of the patients. For example, the proportions of patients with metastatic disease (stage 4) were the greatest among emergency admissions and least among other consultant referrals (table 1). There was also a greater proportion of patients with metastatic disease among urgent (2WW) GP referrals compared to non-urgent referrals (44.9% vs 39.4%, respectively). The difference in the unadjusted rates of curative treatment intent among urgent (2WW) and non-urgent GP referrals was removed after risk-adjustment. However, diagnosis after emergency admission remained an independent predictor of treatment intent. Differences in 1-year survival, consistent with the differences observed in treatment intent, were also found for the various routes to diagnosis (table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between route to diagnosis, curative treatment intent and 1-year survival among patients diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer in English NHS trusts

| Referral source | Patients | Patients with outcome (%) |

Unadjusted OR* | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with curative intent | ||||||

| GP referral: urgent | 6084 | 2167 | (36) | 1 | 1 | |

| GP referral: non-urgent | 2759 | 1096 | (40) | 1.19 | 1.02 | 0.90 to 1.15 |

| Emergency admission | 2178 | 359 | (16) | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.52 to 0.74 |

| Other hospital referral | 2326 | 1059 | (46) | 1.51 | 1.38 | 1.21 to 1.58 |

| All patients | 13347 | 4681 | (35) | |||

| Patients who survive 1 year (%) | ||||||

| GP referral: urgent | 6438 | 2763 | (43) | 1 | 1 | |

| GP referral: non-urgent | 2913 | 1413 | (49) | 1.25 | 1.11 | 1.00 to 1.24 |

| Emergency admission | 2311 | 617 | (27) | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.68 to 0.89 |

| Other hospital referral | 2440 | 1288 | (53) | 1.49 | 1.33 | 1.18 to 1.50 |

| All patients | 14102 | 6081 | (43) | |||

*OR with GP referral: urgent as the baseline category.

†Adjusted OR estimated using multiple logistic regression, adjusting for patients’ age group, sex, tumour site, stage, number of comorbidities, performance status and regional deprivation.

GP, general practitioner.

The routes to diagnosis varied distinctly between cancer networks. Adjusted rates of diagnosis after emergency admission ranged from 8.7% to 32.3%, and six networks fell outside the 99.8% funnel limits (figure 1). There was also substantial variation between the networks in the adjusted rates of urgent (2WW) referral among patients diagnosed after any GP referral. Five networks had adjusted rates above 80%, while four had rates below 60%.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients referred after an emergency admission for the 30 English cancer networks, adjusted for patient age, sex, tumour site, comorbidities, performance status and regional deprivation.

Discussion

This national study of 14 102 patients with O-G cancer adds to the limited evidence how routes to diagnosis are related to treatment outcomes. We found that only 45% of patients were diagnosed after an urgent (2WW) GP referral. Around 21% of patients were referred non-urgently by their GP which suggests their pattern of symptoms were not suggestive of cancer. The remaining third could be grouped evenly into diagnosis after an emergency admission and after referral by another hospital consultant. There was, however, substantial variation between cancer networks in the proportion of patients diagnosed via each route.

The importance of route to diagnosis is highlighted by its relationship to treatment intent and 1-year survival. We found the proportion of patients planned to have curative treatment was considerably lower among patients diagnosed after an emergency admission (16%) compared to urgent (2WW) GP referrals (36%). This was partly owing to differences in the characteristics of patients diagnosed via these routes, with more patients diagnosed after an emergency admission having advanced disease. This suggests that diagnosis after emergency admission is a marker for late diagnosis. In addition, this route to diagnosis occurred more frequently among patients with stomach rather than oesophageal (including junctional) cancer, and was also associated with increasing age, more comorbidity and worse performance status.

The proportion of urgent (2WW) GP referrals was significantly lower among patients aged less than 55 years and this may reflect the age criterion for urgent referral in the guideline on dyspepsia.9 We also observed that the proportion of patients with curative treatment plans was lower among urgent (2WW) GP referrals compared to non-urgent referrals. This is probably owing to the alarm symptoms which form the basis of the referral guidelines being associated with more advanced disease.12 13

Strengths and limitations

The study was based on a large, prospective sample of patients diagnosed in 142 English NHS trusts, 92% of all trusts providing O-G cancer care. Route to diagnosis was defined using items from the English national cancer dataset and 1-year survival was known for all patients.

The study suffers from various limitations. First, using data from the routine Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database, the overall audit was estimated to include 71% of patients diagnosed in England during the data collection period.3 Further exclusion of patient records and NHS trusts with missing data meant this analysis included 62% of all potential cases. The analysed Audit data and HES dataset showed similar demographic characteristics (the average age being 71.4 and 71.3 years, respectively, while the proportions of male patients were 67.2% and 66.3%, respectively). The differences between the analysed and excluded audit patients were also small. Excluded audit patients were slightly younger on average (69.7 vs 71.4 years, p<0.001) but did not differ by a statistically significant amount in terms of patient sex (male 69.2% vs 67.2%, p=0.06) or location of tumour (stomach 29.6% vs 30.8%, p=0.27).

Another limitation was the variation in estimated case ascertainment between networks. Sixteen networks submitted data on over 70% of expected cases, while two submitted less than 40% of cases. Excluding records owing to poor data quality produced marginal changes in case-ascertainment for most networks, with it being reduced by less than 5% for 19 networks. Excluding the 10 NHS trusts, because of poor route to diagnosis, data affected six networks and reduced their case-ascertainment by between 11 and 42%. These exclusions could have biased the individual network rates if hospitals were selective in the patients submitted to the Audit and/or data completeness was related to particular patient characteristics. However, the routes to diagnosis within networks with high, medium and low case-ascertainment were not noticeably different, and selection bias is unlikely to explain the variation observed between networks. Among the nine networks that submitted over 80% of estimated cases and that had less than 5% of records excluded for incomplete data, the adjusted proportion of patients diagnosed after a GP referral ranged from 52% to 71%, while the adjusted proportion of patients diagnosed after emergency admission ranged from 9% to 30%.

A third limitation is that treatment intent was missing for 5% of the 14 102 patients. This might introduce bias in the estimated relationship between referral source and treatment intent, but this is likely to be small compared to the size of the observed association.

Another limitation concerns the information available for risk-adjustment. Many factors can influence decisions about treatment intent and 1-year survival, and there may be residual confounding caused by unmeasured variables such as the symptoms experienced at diagnosis.26 However, the analysis included important prognostic factors such as age, comorbidity, performance status and stage of disease, and residual confounding is unlikely to explain the association between the outcomes and referral source. To incorporate performance status and stage, the analysis used multiple imputations, which relied on the assumption that the data were ‘missing at random’. This assumption seems plausible given the range of variables in the imputation model (see online supplementary material). Finally, the effect of the risk-adjustment on the estimated network rates was comparatively small and it seems unlikely that the observed network variation was owing to inadequate risk-adjustment.

Comparison with other studies

Various studies have examined the pathway to diagnosis, with many focusing on patients diagnosed after an urgent (2WW) GP referral. In a systematic review, Thorne et al27 derived pooled data on 498 patients from seven studies conducted between 2003 and 2008, and estimated that 34% of patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer were diagnosed after an urgent (2WW) GP referral. An audit of cancer diagnosis in English primary care in 2009/ 201028 reported that the proportion of patients with oesophageal cancer (n=596) diagnosed after an urgent (2WW) GP referral and emergency presentation were 58% and 10%, respectively; for stomach cancers (n=319), the proportions were 40% and 21%, respectively. The national study using English Cancer Registry and routine health data18 reported higher rates of emergency presentation (22% for oesophageal and 33% for stomach) and lower rates of urgent (2WW) GP referrals (34% for oesophageal and 23% for stomach).

Our results are generally comparable to these estimates. Compared to the results derived from routine national data,18 we found a higher proportion of diagnoses after an urgent (2WW) GP referral, and a lower proportion after emergency admission. These differences could arise for various reasons. First, the audit may have suffered from potential under-reporting of patients diagnosed via particular pathways. Second, the two studies used different pathway categories and the ‘emergency admission’ definition from the National Cancer dataset and the NCIN definition of emergency presentation may not entirely overlap. Finally, the studies had distinct methodologies. In deriving the results from the routine data, the researchers created eight routes to diagnosis by grouping 71 distinct combinations.18

Few studies have examined the effect of the routes to diagnosis on outcomes for O-G cancer patients. The results of our study are consistent with the evidence that patients diagnosed after emergency have worse survival rates,16 18 29 but we are unaware of any previous study that found, for patients diagnosed after referral by another consultant or a non-urgent GP referral, their risk-adjusted prognosis was not adversely affected.

The reasons for patients being diagnosed after emergency admission are currently unclear. Various explanations have been proposed.29–32 One suggestion is that these patients have more aggressive forms of cancer than patients referred by GPs, or they were asymptomatic prior to presenting at the accident and emergency department. Other explanations are linked to factors delaying diagnosis. Such delays might be patient-related (because the patients ignored their symptoms, did not wish to seek care or did not recognise the seriousness of their symptoms) or might be practitioner related (owing to acid suppression treatment, previous negative tests or initial mis-diagnosis).32

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Recent government policy in England has focused attention on the importance of an efficient pathway to diagnosis by highlighting the worse survival rates for patients diagnosed after emergency presentation.17 This study provides additional insight into this relationship. That patients diagnosed via this route are less likely to have a curative treatment plan compared to urgent (2WW) GP referrals arises in part because more patients have advanced disease. Higher rates of diagnosis after emergency admission were also associated with older patients, greater frailty and more comorbidity.

Further work is required to determine how the risk of emergency admission can be lowered for patients with these characteristics.30 That the risk can be modified is implied by the variation between cancer networks in the proportion of patients diagnosed after emergency admission. The variation suggests the organisation of services, and practices within some networks make this less likely. The lessons to be learnt from these networks require investigation at a local level so that appropriate strategies can be devised.

This study also provides information on outcomes for patients diagnosed after urgent (2WW) and non-urgent GP referrals. The comparatively worse outcomes for patients referred urgently is consistent with the fact that the alarm symptoms used by current referral guidelines are associated with more advanced disease.12 13 There was considerable variation between cancer networks in the proportion of patients referred urgently among all GP referrals. The reasons for this variation remain unknown but it may reflect the clinical uncertainty and debate about the utility of these alarm symptoms as criteria for referral. Further research is required on the symptom profiles of patients referred by GPs as well as causes of delays in diagnosis among O-G cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of all of the health professionals and support personnel in English NHS trusts and Cancer Network for their efforts in submitting the data to the Audit. We would also like to thank Steve Dean and Rose Napper of the Information Centre for Health and Social Care for their assistance in setting up and administering the Audit.

Footnotes

Contributors: TRP, DAC, RHH and SAR conceived the study; TRP, DAC, RHH, SAR, KG and JvdM designed the study; TRP and DAC conducted the statistical analyses; TRP and DAC wrote the manuscript; RHH, SAR, KG and JvdM commented on and revised drafts; DAC is guarantor. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The Audit was commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP).

Competing interests: All authors declare support from Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) for the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK Statistical Information Team. 2011. Common cancers—UK mortality statistics. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/mortality/cancerdeaths/ (accessed 26 Apr 2011)

- 2.Scottish Audit of Gastro-oesophageal Cancer Steering Group Gilbert FJ, Park KGM, Thompson AM. Scottish audit of gastro-oesophageal Cancer. Edinburgh: Information & Statistics Division, NHS Scotland, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cromwell DA, Palser TR, van der Meulen J, et al. The National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit: third annual report. Leeds: The NHS Information Centre, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office for National Statistics. Cancer survival in England—Patients diagnosed 2004−2008, followed up to 2009. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/can0411.pdf (accessed 26 Apr 2011)

- 5.Richards MA. The national awareness and early diagnosis initiative in England: assembling the evidence. Br J Cancer 2009;101(Suppl 2):S1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health Guidance on commissioning cancer services: improving outcomes in upper gastro-intestinal cancers: the manual. London: Department of Health, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodger K, Eastwood PG, Manning SI, et al. Dyspepsia workload in urban general practice and implications of the British Society of Gastroenterology Dyspepsia guidelines. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:413–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heikkinen M, Pikkarainen P, Takala J, et al. General practitioners’ approach to dyspepsia. Survey of consultation frequencies, treatment, and investigations. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:648–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.North of England Dyspepsia Guideline Development Group Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in primary care. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care Referral guidelines for suspected cancer in adults and children. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network SIGN 87—Management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowrey DJ, Griffin SM, Wayman J, et al. Use of alarm symptoms to select dyspeptics for endoscopy causes patients with curable esophagogastric cancer to be overlooked. Surg Endosc 2006;20:1725–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meineche-Schmidt V, Jorgensen T. ‘Alarm symptoms’ in patients with dyspepsia: a three-year prospective study from general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:999–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Audit Office Delivering the cancer reform strategy. London: NAO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health The cancer reform strategy. London: Department of Health, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Intelligence Network (NCIN) Routes to diagnosis—NCIN data briefing. http://www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/routes_to_diagnosis.aspx (accessed 28 Jan 2011)

- 17.Department of Health Improving outcomes: a strategy for cancer. London: Department of Health, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliss-Brookes L, McPhail S, Ives A, et al. Routes to diagnosis for cancer—determining the patient journey using multiple routine data sets. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1220–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palser TR, Cromwell DA, van der Meulen J, et al. The National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit: second annual report. Leeds: The NHS Information Centre, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.The NHS Information Centre Cancer dataset project. Cancer data manual. Version 4.5, Leeds: The NHS Information Centre, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours, International Union against Cancer (UICC). 6th edn New York: Wiley-Liss, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. 2004. The English indices of deprivation 2004: summary (revised) http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100410180038/http://www.communities.gov.uk/archived/publications/communities/indicesdeprivation (accessed 1 Nov 2009)

- 23.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd edn Chichester: Wiley & Sons, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiegelhalter DJ. Funnel plots for comparing institutional performance. Stat Med 2005;24:1185–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update of ICE. Stata J 2005;5:527–36 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Identifying patients with suspected gastro-oesophageal cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:707–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorne K, Hutchings H, Elwyn G. The two-week rule for NHS gastrointestinal cancer referrals: a systematic review of diagnostic effectiveness. Open Colorectal Cancer J 2009;2:27–33 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin G, McPhail S, Elliott K. National audit of cancer diagnosis in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackshaw GR, Stephens MR, Lewis WG, et al. Prognostic significance of acute presentation with emergency complications of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2004;7:91–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton W. Emergency admissions of cancer as a marker of diagnostic delay. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1205–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottle A, Tsang C, Parsons C, et al. Association between patient and general practice characteristics and unplanned first-time admissions for cancer: observational study. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1213–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald S, Macleod U, Campbell NC, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing patient and practitioner delay in diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;94:1272–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.