Abstract

Background

Although many etiological theories have been proposed for osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), its etiology remains unclear. Histological analysis of the articular cartilage and subchondral bone tissues of OCD lesions can provide useful information about the cellular changes and progression of OCD. Previous research is predominantly comprised of retrospective clinical studies from which limited conclusions can be drawn.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were threefold: (1) Is osteonecrosis a consistent finding in OCD biopsy specimens? (2) Is normal articular cartilage a consistent finding in OCD biopsy specimens? (3) Do histological studies propose an etiology for OCD based on the tissue findings?

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL databases for studies that conducted histological analyses of OCD lesions of the knee and identified 1560 articles. Of these, 11 met our inclusion criteria: a study of OCD lesions about the knee, published in the English language, and performed a histological analysis of subchondral bone and articular cartilage. These 11 studies were assessed for an etiology proposed in the study based on the study findings.

Results

Seven of 11 studies reported subchondral bone necrosis. Four studies reported normal articular cartilage, two studies reported degenerated or irregular articular cartilage, and five studies found a combination of normal and degenerated or irregular articular cartilage. Five studies proposed trauma or repetitive stress and two studies proposed poor blood supply as possible etiologies.

Conclusions

We found limited research on histological analysis of OCD lesions of the knee. Future studies with consistent methodology are necessary to draw major conclusions about the histology and progression of OCD lesions. Inconsistent histologic findings have resulted in a lack of consensus regarding the presence of osteonecrosis, whether the necrosis is primary or secondary, the association of cartilage degeneration, and the etiology of OCD. Such studies could use a standardized grading system to allow better comparison of findings.

Introduction

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a disorder of the joint that may cause progressive changes in the subchondral bone and associated articular cartilage, including softening, swelling, early separation, partial detachment, or complete osteochondral separation with a loose body. In 1840, Paré first described the removal of loose bodies from joints, believed to be from osteochondral lesions [18, 23]. This condition was described as “quiet necrosis” by Sir James Paget in 1870 [17] and later termed “osteochondritis dissecans” by König in 1888, who proposed that an inflammatory reaction in the bone and articular cartilage caused spontaneous necrosis [11].

Other causes of OCD have been proposed, including genetic predisposition, ischemia, and repetitive or acute trauma. Several reports have identified patients with OCD within families and among several generations, although many of these reports were in families with dwarfism or short stature [1, 12, 19, 26, 27]. Ischemia has also been proposed as a cause of OCD [3, 5, 14], although whether this is a primary cause, a secondary effect of trauma, or other pathophysiology is unclear. Fairbank’s [6] theory, later advocated by Smillie [24], was that repetitive microtrauma caused OCD of the knee. Trauma, either acute or repetitive microtrauma, has become a more accepted cause of OCD as a result of the high incidence of this disorder in the athletic population [2, 4, 6, 7, 10, 13, 14, 16, 28]. Despite the current consensus, the etiology of OCD remains unknown, and it may be multifactorial.

The purpose of this study was to perform a review of the current literature on histological and/or immunochemical analysis of OCD lesions of the knee to determine if the pathologic changes provide insight about the progression or etiology of this condition. The more specific focus of this review was to answer three questions: (1) Is osteonecrosis a consistent finding in OCD biopsy specimens? (2) Is normal articular cartilage a consistent finding in OCD biopsy specimens? (3) Do histological studies propose an etiology for OCD based on the tissue findings?

Search Strategy and Criteria

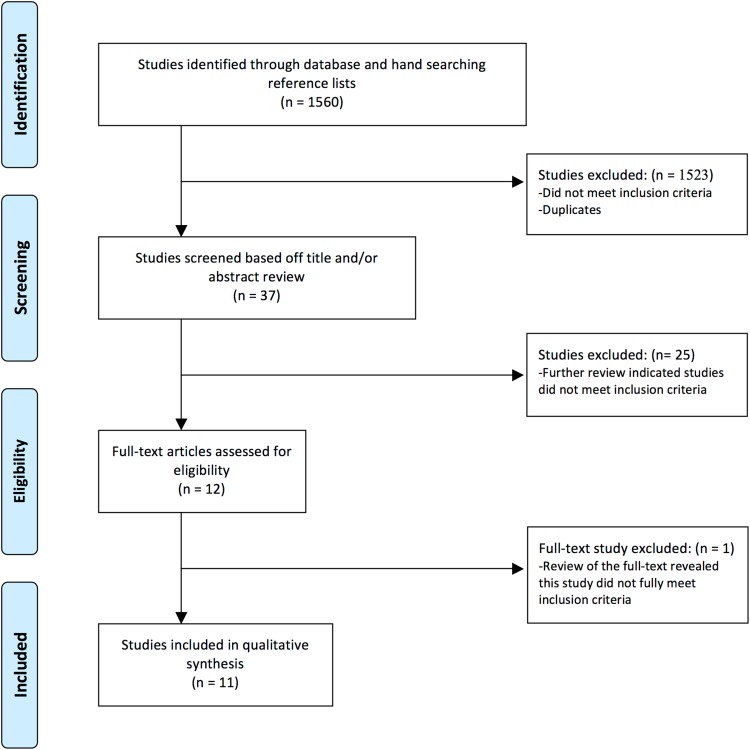

To identify studies on histological analyses of OCD lesions in the knee, two of us (KGS, JCJ) performed the following search in December 2011 after consulting a research strategist (MM): (histology OR histologic OR histol* OR biopsy OR biopsies) AND (osteochondritis dissecans OR osteochondrosis) (Fig. 1). The search was conducted in Medline (1946-2011), Embase (1947-2011), and CINAHL (1982-2011) databases. We assessed initial references obtained by the mentioned searches for inclusion criteria by a review of the article title and/or abstract. The search of the literature identified 1282 initial references in MEDLINE, 230 in EMBASE, and 48 in CINAHL.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

We included all studies of OCD lesions about the knee published in English that used a histological analysis of subchondral bone and the associated articular cartilage. This analysis could include immunochemistry or morphology, if reported. Historically, other terms have been associated with OCD, including osteochondral fractures, osteonecrosis, and osteochondral fragments [23]. We omitted these search terms because we presumed they were less likely to represent the current definition of OCD. We excluded studies that only evaluated articular cartilage without additional bone analysis or only reported followup treatment of OCD (ie, autologous cartilage implantation). Studies were not excluded based on the age of the subjects or severity of the OCD lesion. With these inclusion/exclusion criteria we identified 12 articles for which we obtained full texts; we then performed full-text reviews to ensure the articles met the inclusion criteria. Two of us (KGS, JCJ) independently evaluated all titles, abstracts, and full-text reviews. Of these 12 articles, one was excluded that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We appraised study methodologies for histological evaluation and the findings and conclusions of the studies were compared. After removing duplicates, all authors were in agreement for the 11 studies that met the inclusion criteria.

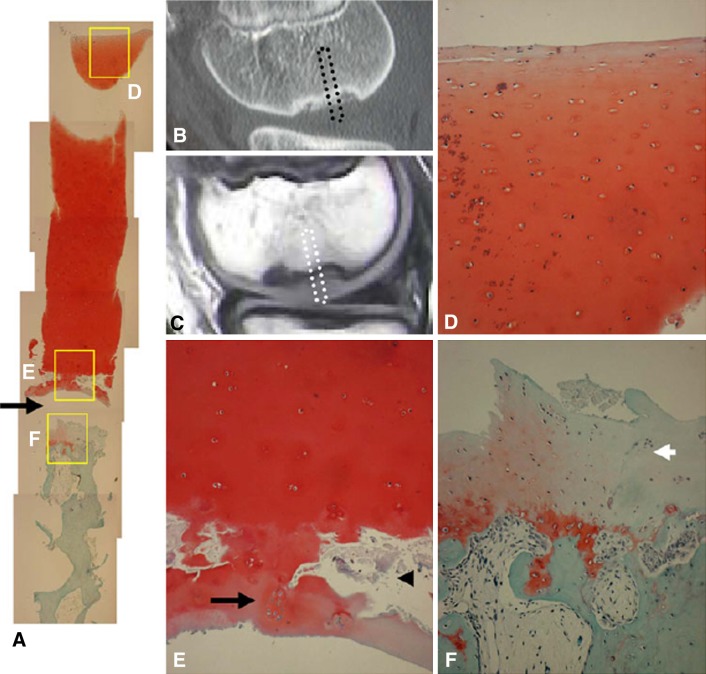

The 11 publications were reviewed for the source of the specimen, whether from a free OCD fragment, the underlying bone, or both. We classified specimens that arose from the OCD fragment as progeny bone/cartilage tissue. Specimens from the underlying bone were classified as parent bone (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Osteochondral plug harvested from the center of the lesion. A cleft separates the plug into two parts: a fragment side (F) and a basal side (B). Reprinted with permission from Uozumi H, Sugita T, Aizawa T, Takahashi A, Ohnuma M, Itoi E. Histologic findings and possible causes of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2003–2008.

The studies included in this review used different methodologies for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Some studies did not report on their fixation and/or decalcification protocols (if used) [3, 8–10, 16, 30, 31]. Some only used photomicrographs (without staining) [3, 8, 9] and several different histological techniques were used.

For fixation of the OCD specimens, four standard agents were used with varying concentrations and/or other chemicals (Table 1). Of the 11 studies, four used formalin (varying concentrations) [10, 14, 28, 31], one study each used formaldehyde 10% [4] or alcohol [20], and five did not report a fixation agent [3, 8, 9, 16, 30]. Decalcification agents used among the studies varied: one study used 5% nitric acid and 70% alcohol [4], one study used 40% formic acid and 20% sodium citrate [14], one study used EDTA [28], one study reported that no decalcification was used [20], and seven did not report on decalcification [3, 8–10, 16, 30, 31]. For histological analysis, six separate stains/analyses were used with varying frequency (Table 1). Six studies used hematoxylin and eosin [4, 14, 16, 28, 30, 31], two used Safranin-O (one in combination with Fast-Green) [14, 31], one used toluidine blue [14], one used Alcian blue [10], one study used von Kossa stain [10], one study used Gomori trichrome stain [10], and one study used Goldner stain [14]. Two studies preoperatively labeled with tetracycline [14, 20] and three studies did not use any staining techniques and only observed cross-sections through photomicrographs [3, 8, 9].

Table 1.

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

| Author | Year | Journal | Fixation | Decalcification | Histological analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H/E | Safranin-O | Immunohistochemistry | Toluidine blue | Alcian blue | |||||

| Campbell and Ranawat [3] | 1966 | J Trauma | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chiroff and Cooke [4] | 1975 | J Trauma | Formaldehyde 10% | 5% nitric acid and 70% alcohol | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Green and Banks [8] | 1953 | JBJS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| King [9] | 1932 | JBJS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Koch et al. [10] | 1997 | KSSTA | Formalin 4% | – | – | – | Yes | – | Yes |

| Linden and Telhag [14] | 1977 | Acta Orthop Scand | Formalin 10% (buffered) | 40% formic acid and 20% sodium citrate | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – |

| Milgram [16] | 1978 | Radiol | – | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Portigliatti Barbos et al. [20] | 1985 | Ital J Orthop Traumatol | Alcohol | None | – | – | – | – | – |

| Uozumi et al. [28] | 2009 | AJSM | Formalin 10% | EDTA | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Yonetani et al. [31] | 2010 | KSSTA | Formalin 10% | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – |

| Yonetani et al. [30] | 2010 | Arthroscopy | – | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Author | Year | Journal | Histological analysis | Immunochemical analysis | Additional comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Von Kossa stain | Gomorri trichrome stain | Goldner stain | Tetracycline Labeling | Collagen Type I | Collagen Type II | ||||

| Campbell and Ranawat [3] | 1966 | J Trauma | – | – | – | – | – | – | Staining techniques not reported |

| Chiroff and Cooke [4] | 1975 | J Trauma | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Green and Banks [8] | 1953 | JBJS | – | – | – | – | – | – | Staining techniques not reported |

| King [9] | 1932 | JBJS | – | – | – | – | – | – | Staining techniques not reported |

| Koch et al. [10] | 1997 | KSSTA | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes | – |

| Linden and Telhag [14] | 1977 | Acta Orthop Scand | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – |

| Milgram [16] | 1978 | Radiol | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Portigliatti Barbos et al. [20] | 1985 | Ital J Orthop Traumatol | – | – | – | Yes | – | – | – |

| Uozumi et al. [28] | 2009 | AJSM | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yonetani et al. [31] | 2010 | KSSTA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yonetani et al. [30] | 2010 | Arthroscopy | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

H/E = hematoxylin and eosin; JBJS = Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; KSSTA = Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy; AJSM = American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Only the study by Koch et al. [10] conducted an immunohistochemical analysis. They found OCD lesions had Type I and Type II collagen in a normal distribution (Table 1). None of the studies included in the review used a histological grading system.

In addition to the variation in histological analysis of the specimens, the source of the specimens and biopsy dimensions, if reported, also had substantial variability (Table 2). A majority of the studies analyzed specimens from medial femoral condyle lesions (Table 2). Four studies only reported the histology of the progeny fragments that were removed from the knee [4, 8, 9, 16] and six studies reported histology of the progeny fragments and the associated parent bone with inconsistent methodology [3, 10, 14, 20, 28, 31]. One study collected biopsy specimens from both the progeny fragment and parent bone but did not report these separately [30].

Table 2.

Tissue source for histological analysis

| Author | Year | Journal | Loose body/excised fragment | Progeny and parent | Lesion location | Cylindrical biopsy dimension (width × length) | Histological analysis, section thickness | Time from subjective symptom onset to surgery, mean (range) | Time from diagnosis to biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell and Ranawat [3] | 1966 | J Trauma | – | Yes | MFC | – | – | – | – |

| Chiroff and Cooke [4] | 1975 | J Trauma | Yes | – | – | – | – | 3–10 years* | – |

| Green and Banks [8] | 1953 | JBJS | Yes | – | MFC | – | – | Approximately 14 and 18 months | Approximately 17 and 2 months |

| King [9] | 1932 | JBJS | Yes | – | MFC | – | – | Acute, approximately 3 years | – |

| Koch et al. [10] | 1997 | KSSTA | – | Yes | – | – | 10 mm | – | – |

| Linden and Telhag [14] | 1977 | Acta Orthop Scand | – | Yes | MFC | 2 mm | 7 mm | 4.9 years (9 months to 17 years) | – |

| Milgram [16] | 1978 | Radiol | Yes | – | – | – | – | 1.5 years, several years, 10 years† | – |

| Portigliatti Barbos et al. [20] | 1985 | Ital J Orthop Traumatol | – | Yes | 8 MFC, 3 LFC, 1 both | – | 30–40 μm | – | – |

| Uozumi et al. [28] | 2009 | AJSM | – | Yes | MFC | 6–10 mm × 20 mm | – | 1–60 months | – |

| Yonetani et al. [31] | 2010 | KSSTA | – | Yes | MFC | 14-gauge biopsy needle | 4 mm | 17 months (5–24 months) | – |

| Yonetani et al. [30] | 2010 | Arthroscopy | Unclear | Unclear | 6 MFC, 2 LFC, 1 trochlea | 14-gauge biopsy needle, 20-mm depth | – | 1 week to 9 months* | – |

* One case was unknown; †of 50 cases, subjective symptom onset was reported only in three; JBJS = Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; KSSTA = Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy; AJSM = American Journal of Sports Medicine; MFC = medial femoral condyle; LFC = lateral femoral condyle.

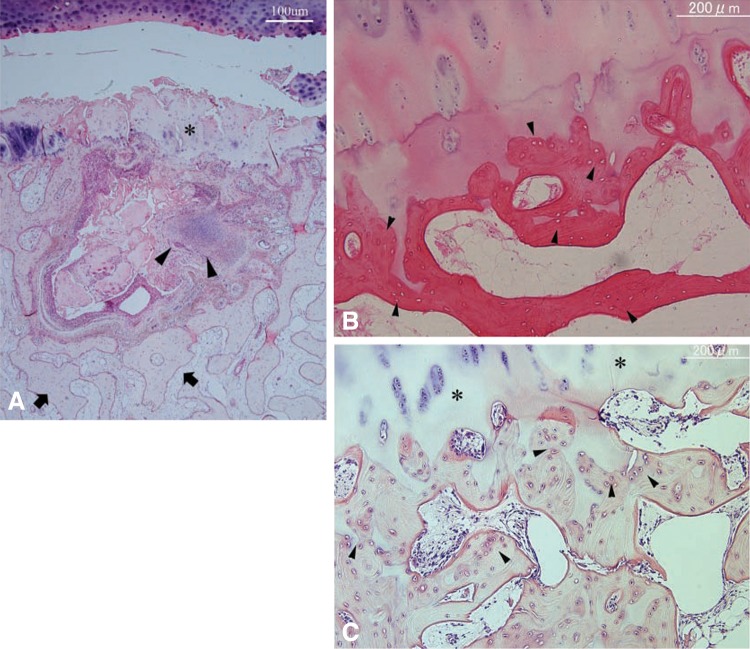

The presence of subchondral bone necrosis was determined by the studies from the results of their histological analyses, if used. Study authors per the findings of their histological analyses assessed articular cartilage viability (Fig. 3). Etiology was reported by the authors of the study reviewed based on their findings.

Fig. 3A–F.

Safranin-O staining of cylindrical tissue sample with wide homogeneous cartilage (Patient 2). (A) Entire view of the slide (original magnification, ×40). Separation site (arrow). (B) CT image, sagittal view. (C) MRI T1-weighted image of the OCD lesion. Cylindrical tissue sample was obtained from central portion (dotted square). (D) Superficial layer of articular cartilage showing normal appearance of chondrocytes, no degenerative change, and no decrease of Safranin-O staining. (E) Cloning of chondrocytes (black arrow) and microfracture (arrowhead) were observed in the deep end of the cartilage layer just above the separation site. (F) Cartilage tissue with decreased Safranin-O staining was observed over the normal subchondral bone trabeculae. Fibrous tissue with blood vessels was observed within normal trabecular bone (D–F, original magnification, ×100). Reproduced with permission from Yonetani Y, Nakamura N, Natsuume T, Shiozaki Y, Tanaka Y, Horibe S. Histological evaluation of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: a case series. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:723–730.

Results

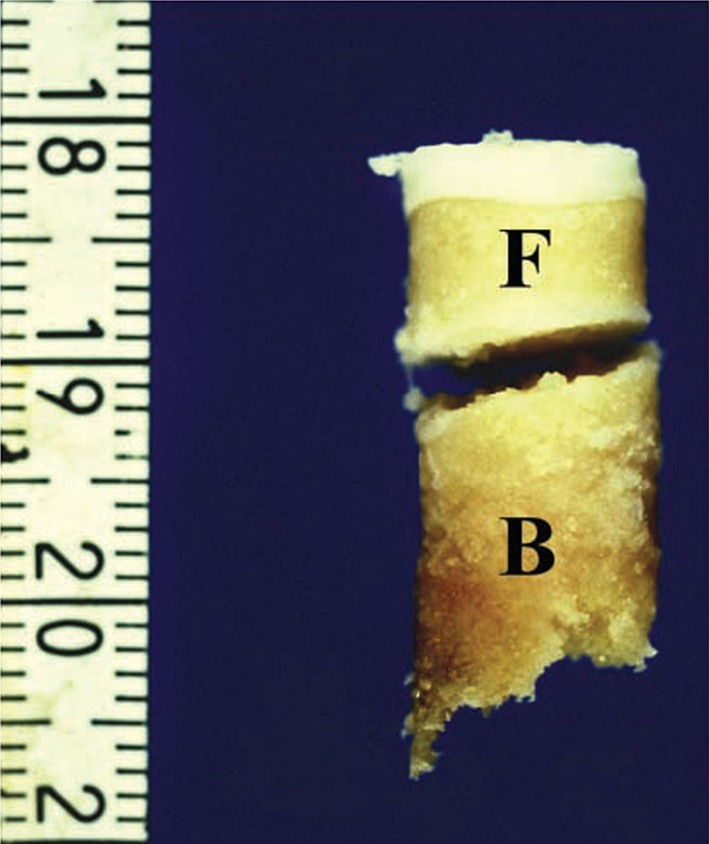

Ten of the 11 studies evaluated the subchondral bone for necrosis (Fig. 4) [3, 4, 8, 10, 14, 16, 20, 28, 30, 31]. Seven studies reported subchondral bone necrosis [3, 8, 14, 16, 20, 28, 30], two found no subchondral bone necrosis [4, 31], and one found samples were often not necrotic [10].

Fig. 4A–C.

(A) Photomicrograph of the basal side of the osteochondral plug. The surface is covered with fibrillated cartilaginous tissue (asterisk). Beneath the surface, active bone remodeling (arrowheads) with proliferation of fibrovascular tissue, bone formation, and bone resorption is evident. The deep area (arrows) is composed of normal trabeculae and marrow tissue (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×20). (B) Photomicrograph of the deep area of the fragment side indicating necrotic subchondral trabeculae, because many of the lacunae are empty (arrowheads) (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×40). (C) Photomicrograph of the deep area of the fragment side showing viable subchondral trabeculae, because osteocytes are detected in the lacunae (arrowheads). The superficial part of this area consists of articular cartilage (asterisks) (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×40). Reproduced with permission from Uozumi H, Sugita T, Aizawa T, Takahashi A, Ohnuma M, Itoi E. Histologic findings and possible causes of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2003–2008.

The details of articular cartilage findings in OCD lesions of the knee varied widely in the studies of this review. Four studies reported normal articular cartilage [4, 14, 20, 28]. Five studies found a combination of normal articular cartilage and degenerated or irregular articular cartilage [8, 9, 16, 30, 31]. Two studies reported only degenerated or irregular articular cartilage findings [3, 10].

Six of the 11 studies proposed an etiology for OCD (Table 3). Five studies proposed trauma or repetitive stress as the etiology [4, 10, 14, 16, 28]. Two studies proposed that OCD was the result of poor blood supply to the area [3, 14].

Table 3.

Summary of findings

| Author | Year | Journal | Subchondral bone necrosis | Proposed relationship between findings and etiology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma or repetitive stress | Poor blood supply | ||||

| Campbell and Ranawat [3] | 1966 | J Trauma | Yes | – | Yes |

| Chiroff and Cooke [4] | 1975 | J Trauma | No | Yes | – |

| Green and Banks [8] | 1953 | JBJS | Yes | – | – |

| King [9] | 1932 | JBJS | – | – | – |

| Koch et al. [10] | 1997 | KSSTA | Often not necrotic | Yes | – |

| Linden and Telhag [14] | 1977 | Acta Orthop Scand | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Milgram [16] | 1978 | Radiol | Yes | Yes | – |

| Portigliatti Barbos et al. [20] | 1985 | Ital J Orthop Traumatol | Yes | – | – |

| Uozumi et al. [28] | 2009 | AJSM | Yes | Yes | – |

| Yonetani et al. [31] | 2010 | KSSTA | No | – | – |

| Yonetani et al. [30] | 2010 | Arthroscopy | Yes | – | – |

JBJS = Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; KSSTA = Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy; AJSM = American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Discussion

Despite König defining OCD in 1888, many theories still exist today regarding the possible etiogenic factors of OCD. MRI and arthroscopy are useful in evaluating OCD; however, these modalities provide little insight into the cause of this condition. Histological analysis can provide important observations about the condition of the bone and cartilage that could be used to determine the etiology and progression of OCD. We focused on several areas relevant to the pathophysiology for OCD of the knee, including: (1) presence of necrosis; (2) articular condition; and (3) proposed etiology.

We identified a number of limitations in the published literature. First, we found marked variation in analytical histological techniques between studies (Table 1), from microscopic examination of photomicrographs to the use of multiple stains on one specimen. Second, the biopsy location of specimens also had a high degree of variability (Table 2). One biopsy from a lesion is also not necessarily representative of the entire tissue of the OCD lesion. Third, the time from subjective symptom onset to diagnosis and from diagnosis to biopsy was not consistently reported. Fourth, this review only included case series or case reports. To our knowledge, there are no published studies with better methodology. Fifth, these histological studies of biopsies of bone and cartilage from OCD lesions are typically obtained only in the later, symptomatic stages of the condition because surgery is typically performed only on symptomatic patients. We found the biopsy specimens were obtained from 1 week to 10 years after onset of symptoms [4, 8, 9, 14, 16, 28, 30, 31]. Specimens from early-stage disease would be valuable but are not available, because it is unethical to remove this tissue at this stage of disease. Sixth, a limitation of our methodology is that our review was limited to articles published in English. We chose to limit the review to the knee, because this is the most common joint affected by this condition. At the initiation of the study, the group consensus was that including other joints with a diagnosis of OCD might make the results more variable and less focused on one anatomic area. Seventh, we excluded the terms osteochondral fractures, osteonecrosis, and osteochondral fragments. This exclusion may have reduced the number of relevant publications on this condition as a result of the overlap and evolution of the terms related to OCD. The impact of this strategy was mitigated by manually searching the references from the final list of studies.

Of the 11 studies we reviewed, necrosis of the subchondral bone was identified in seven of the 10 that evaluated for the presence of necrosis [3, 8, 14, 16, 20, 28, 30]. Inconsistent methodology of the studies precludes definitive conclusions regarding the etiology of OCD. The studies reviewed did not clarify the stage or chronicity of the OCD, and thus, it was difficult to determine if the biopsies were performed early or late in the stage of OCD. It is unclear from this review if the presence of necrosis in subchondral bone in seven of the 10 studies is primary or secondary to the pathogenesis of OCD. The histological appearance of the necrotic bone in OCD is consistent with vascular occlusion [5, 23]. Enneking [5] described the vascularity of the subchondral bone as an end arterial arcade much like that of the gastrointestinal mesentery with poor anastomoses. He proposed that insufficient arterial branching could produce infarction of subchondral bone that progresses to form an OCD. Trauma could then cause the articular cartilage to fracture and result in a loose body within the joint. Several studies have questioned the presence of an ischemic zone in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle [4, 10, 21, 22]. Furthermore, the ischemic zone theory seems implausible when OCD is more common in young patients, because these patients probably have a good distal femoral blood supply [29], and OCD lesions occur in other locations in the knee.

Nine of the 11 studies reported normal articular cartilage in all or part of their specimens, whereas seven studies reported degenerated or irregular cartilage. Both the methods and description of cartilage findings varied between studies.

Although the presence of subchondral bone necrosis is consistent with the theory of vascular occlusion, necrosis may be caused by other mechanisms [2]. Repetitive microtrauma to the subchondral bone may cause a stress fracture phenomenon [25], leading to necrosis in the progeny fragment. In this scenario, bone necrosis could be considered secondary to trauma rather than secondary to a local primary vascular insult [2]. Six of the studies comment on how the findings of their study relate to either the course of OCD development or etiology of the disorder. Possible etiologic causes still include trauma or repetitive stress [4, 10, 14, 16, 28] and poor blood supply [3, 14].

We identified several areas for future research. A majority of the studies identified for review were retrospective case series. Prospective studies of OCD lesions should be conducted with larger sample sizes using consistent techniques and a validated grading scale for both cartilage and subchondral bone. The International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) II grading scale, which evaluates both articular cartilage and subchondral bone, could be used to conduct histological analyses of osteochondritis dissecans biopsy specimens to standardized methodology [15]. The ICRS II has an associated protocol for the biopsy of specimens and procedure for the histological analysis. However, one limitation of this grading system is that it has an emphasis on findings within the articular cartilage. Because OCD cases frequently contain substantial changes in the subchondral bone, a more vivid set of descriptive criteria may be necessary for subchondral bone. Most of the histological studies on OCD have focused on the bone from the abnormal cartilage/bone area, or the “progeny” fragment. The normal, parent bone underlying the lesion should also be analyzed with histological and/or immunochemical methods.

Future studies should report time from the subjective onset of symptoms to diagnosis and time from diagnosis to biopsy. It is assumed that the secondary cartilage changes in OCD occur after progressive change (advanced or prolonged periods of bone necrosis, increased volume of bone involvement, or mechanical collapse of the underlying bone) in the bone. However, to definitively determine the order of events in disease progression, longitudinal studies will be required to directly assess the temporal changes within the joint, combining the analysis of subchondral bone changes with assessment of biomarkers of cartilage degeneration within the synovial fluid. Additionally, future research, including the use of cartilage sequences on more powerful MRI scanners, may help address the presence and staging of associated cartilage changes with OCD.

There is a paucity of research using consistent histological techniques for OCD lesions in the knee that assesses both the subchondral bone and articular cartilage. Within the studies that were reviewed, there was very limited immunohistochemical analysis of the articular cartilage in OCD lesions. Subchondral bone necrosis was noted in most of the studies reviewed. In those studies that commented on specific etiological factors, trauma, repetitive stress, and poor vascularity were most frequently proposed. Future studies using standardized histological and immunohistochemical methodologies need to be conducted for OCD to better determine etiology and optimal treatment strategies. These studies should include an analysis of both the parent and progeny bone in their analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Eric Wall, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, for his substantial contributions to this review. We also thank Mary McFarland, Information & Technology Consultant, Eccles Health Sciences Library, University of Utah School of Medicine, for consultation in the search strategy.

Footnotes

Funding provided by the INBRE Program (JTO), National Institutes of Health grants P20 RR016454 (National Center for Research Resources), and P20 GM103408 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

References

- 1.Andrew TA, Spivey J, Lindebaum RH. Familial osteochondritis dissecans and dwarfism. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:519–523. doi: 10.3109/17453678108992141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cahill BR. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: treatment of juvenile and adult forms. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:237–247. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell CJ, Ranawat CS. Osteochondritis dissecans: the question of etiology. J Trauma. 1966;6:201–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiroff RT, Cooke CP., 3rd Osteochondritis dissecans: a histologic and microradiographic analysis of surgically excised lesions. J Trauma. 1975;15:689–696. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197508000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enneking WF. Clinical Musculoskeletal Pathology. 1990. University Press of Florida. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=20727&site=ehost-live. Accessed December 15, 2011.

- 6.Fairbank HA. Osteochondritis dissecans. Br J Surg. 1933;21:67–73. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800218108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green JP. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48:82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green WT, Banks HH. Osteochondritis dissecans in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35:26–47; passim. [PubMed]

- 9.King D. Osteochondritis dissecans: a clinical study of twenty-four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1932;14:535–544. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch S, Kampen WU, Laprell H. Cartilage and bone morphology in osteochondritis dissecans. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:42–45. doi: 10.1007/s001670050023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.König F. [About free body in the joints] [in German] Zeiteschr Chir. 1888;27:90–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02792135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozlowski K, Middleton R. Familial osteochondritis dissecans: a dysplasia of articular cartilage? Skeletal Radiol. 1985;13:207–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00350575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krappel FA, E B, U H. Are bone bruises a possible cause of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum? A case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:545–549. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linden B, Telhag H. Osteochondritis dissecans. A histologic and autoradiographic study in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48:682–686. doi: 10.3109/17453677708994817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mainil-Varlet P, Van Damme B, Nesic D, Knutsen G, Kandel R, Roberts S. A new histology scoring system for the assessment of the quality of human cartilage repair: ICRS II. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:880–890. doi: 10.1177/0363546509359068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milgram JW. Radiological and pathological manifestations of osteochondritis dissecans of the distal femur. A study of 50 cases. Radiology. 1978;126:305–311. doi: 10.1148/126.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paget J. On the production of some of the loose bodies in joints. Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital Reports. 1870;6.

- 18.Paré A, Malgaigne JF. [Complete works of Ambroise Paré] [in French] Paris, France: J.-B. Baillière; 1840. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips HO, Grubb SA. Familial multiple osteochondritis dissecans. Report of a kindred. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:155–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portigliatti Barbos M, Brach del Prever E, Borroni L, Salvadori L, Battiston B. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. A histological study with pre-operative fluorescent bone labelling and microradiography. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1985;11:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy AS, Frederick RW. Evaluation of the intraosseous and extraosseous blood supply to the distal femoral condyles. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:415–419. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers WM, Gladstone H. Vascular foramina and arterial supply of the distal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:867–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schenck RC, Jr, Goodnight JM. Osteochondritis dissecans. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:439–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smillie IS. Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39:248–260. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.39B2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokoloff RM, Farooki S, Resnick D. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee associated with ipsilateral tibial plateau stress fracture: report of two patients and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:53–56. doi: 10.1007/s002560000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stattin EL, Tegner Y, Domellof M, Dahl N. Familial osteochondritis dissecans associated with early osteoarthritis and disproportionate short stature. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stougaard J. Familial occurrence of osteochondritis dissecans. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:542–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uozumi H, Sugita T, Aizawa T, Takahashi A, Ohnuma M, Itoi E. Histologic findings and possible causes of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2003–2008. doi: 10.1177/0363546509346542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall E, Von Stein D. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yonetani Y, Matsuo T, Nakamura N, Natsuume T, Tanaka Y, Shiozaki Y, Wakitani S, Horibe S. Fixation of detached osteochondritis dissecans lesions with bioabsorbable pins: clinical and histologic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yonetani Y, Nakamura N, Natsuume T, Shiozaki Y, Tanaka Y, Horibe S. Histological evaluation of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: a case series. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:723–730. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0898-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]