Abstract

Objective

To explore the relational challenges for general practitioner (GP) leaders setting up new network-centric commissioning organisations in the recent health policy reform in England, we use innovation network theory to identify key network leadership practices that facilitate healthcare innovation.

Design

Mixed-method, multisite and case study research.

Setting

Six clinical commissioning groups and local clusters in the East of England area, covering in total 208 GPs and 1 662 000 population.

Methods

Semistructured interviews with 56 lead GPs, practice managers and staff from the local health authorities (primary care trusts, PCT) as well as various healthcare professionals; 21 observations of clinical commissioning group (CCG) board and executive meetings; electronic survey of 58 CCG board members (these included GPs, practice managers, PCT employees, nurses and patient representatives) and subsequent social network analysis.

Main outcome measures

Collaborative relationships between CCG board members and stakeholders from their healthcare network; clarifying the role of GPs as network leaders; strengths and areas for development of CCGs.

Results

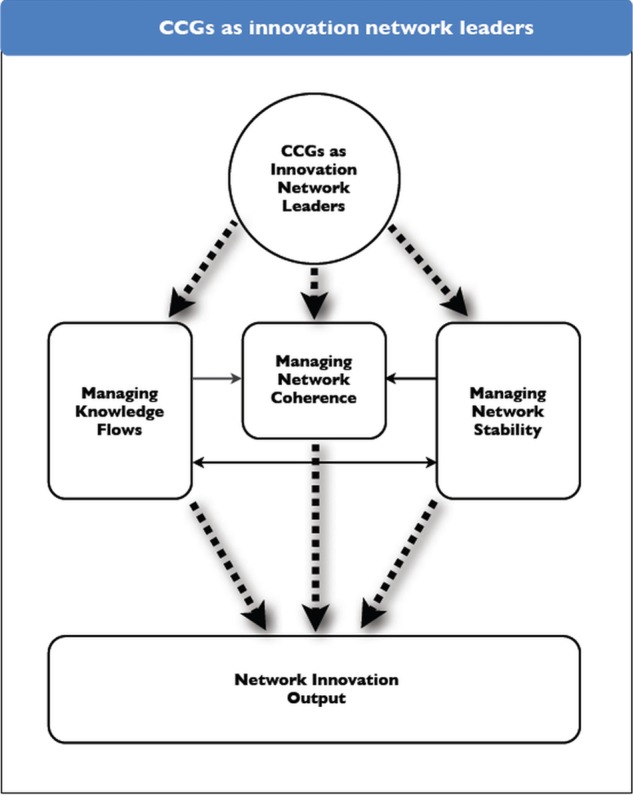

Drawing upon innovation network theory provides unique insights of the CCG leaders’ activities in establishing best practices and introducing new clinical pathways. In this context we identified three network leadership roles: managing knowledge flows, managing network coherence and managing network stability. Knowledge sharing and effective collaboration among GPs enable network stability and the alignment of CCG objectives with those of the wider health system (network coherence). Even though activities varied between commissioning groups, collaborative initiatives were common. However, there was significant variation among CCGs around the level of engagement with providers, patients and local authorities. Locality (sub) groups played an important role because they linked commissioning decisions with patient needs and brought the leaders closer to frontline stakeholders.

Conclusions

With the new commissioning arrangements, the leaders should seek to move away from dyadic and transactional relationships to a network structure, thereby emphasising on the emerging relational focus of their roles. Managing knowledge mobility, healthcare network coherence and network stability are the three clinical leadership processes that CCG leaders need to consider in coordinating their network and facilitating the development of good clinical commissioning decisions, best practices and innovative services. To successfully manage these processes, CCG leaders need to leverage the relational capabilities of their network as well as their clinical expertise to establish appropriate collaborations that may improve the healthcare services in England. Lack of local GP engagement adds uncertainty to the system and increases the risk of commissioning decisions being irrelevant and inefficient from patient and provider perspectives.

Keywords: Health Services Administration & Management, Qualitative Research

Article summary.

Article focus

Examines how clinical commissioning group leaders can act as relational catalysts across their healthcare networks as they seek to facilitate healthcare innovation in light of the recent reform in the healthcare sector in England.

Key messages

The new clinical commissioning scheme foregrounds the need for leaders to be relational and effective in integrating across innovation networks.

Knowledge sharing and collaboration between stakeholder groups are key tasks of clinical leadership which play a significant role in ensuring network coherence and stability.

Lack of clear political direction and dialogue discourages network participation and catalyses instability.

Clinical leaders need to focus on aligning patient-centred services locally as well as across the network.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study provides in-depth accounts of the emerging role of GPs as healthcare network leaders in the early stages of the new commissioning process.

We highlight the relational focus of the network leadership role which enables knowledge sharing, network coherence and network stability.

The use of multimethod approach (interviews, observations of CCG board meetings, extensive study of documentation and CCG network analysis) allowed us to validate our findings and minimise bias owing to limitations of specific methods.

The on-going change in the health sector and the political uncertainty limits the generalisability of this qualitative research.

Introduction

Following the announcement of the latest NHS reform,1 the health system in England has entered a new cycle of radical changes that aim to improve healthcare outcomes and increase efficiency. At the centre of the strategy proposed by the current coalition government is the goal to ‘liberate the NHS’ by putting clinicians such as general practitioners (GPs) ‘in the driving seat and set hospitals free to innovate, with stronger incentives to adopt best practice’,1 thus, challenging the way the commissioning of healthcare services is organised and executed. In this context, the new Health and Social Care Bill creates a duty for the new clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to ‘promote research and innovation and the use of research evidence’.

The commissioning of healthcare services is traditionally understood to be the process by which ‘the health needs of a population are assessed, the responsibility is taken for ensuring that appropriate services are available which meet these needs, and the accountability for the associated health outcomes is established’.2 Until recently, commissioning activities such as planning (assessment and evaluation), purchasing (identifying and negotiating) and monitoring health services3 4 were performed primarily by non-clinical managers in primary care trusts (PCTs) with little clinical input. In response to that the recent reform transferred commissioning duties over to GPs, nurses and other healthcare professionals who represent a range of both provider and purchasing interests. The diversity of the actors involved as well as the complexity of the tasks demands a more integrated approach to commissioning than performed earlier.

Based on the NHS White Paper,1 apart from establishing population needs and planning and controlling their budgets, commissioners must also work with a wider group of stakeholders to identify opportunities to improve value through innovation. This new approach to clinical commissioning shifts from contracting of stand-alone healthcare services based on dyadic relationships to a more dynamic network-centric approach of the healthcare system that brings together a large number of actors to collaborate and purchase integrated services which will deliver the desired outcomes. Recent research emphasises on the importance of networks in healthcare practice and argues that healthcare and clinical networks have the potential to enable multidisciplinary coalitions to address diverse agendas and achieve best practices. Integrating across networks, by allowing for the people and ideas to come together, can also prevent fragmentation, which has been a key challenge of previous commissioning arrangements, and facilitate integrated care with the development of collective contracts that can be more cost-effective and focus on new pathways and care packages, thus, increasing the quality of services and outcomes.5–7

Given the importance of networks in healthcare and the fact that innovation is inherent in, and central to, the new commissioning structure, we used an innovation network theory to study the newly established clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) (figure 2). GP leaders are seen as network leaders within their healthcare service environment with CCGs being the nucleus of innovation activity. Drawing upon this theory, we were able to obtain unique insights of the emerging leadership activities of GPs and their efforts to establish best practices as well as to develop new clinical services tailored to the needs of their population. We believe that this approach will shed light on the emerging forms and functions of evolving commissioning entities and will offer a fresh viewpoint on clinical leadership in healthcare networks.

Figure 2.

Clinical commissioning groups as innovation network leaders.

Clinical commissioning and healthcare networks

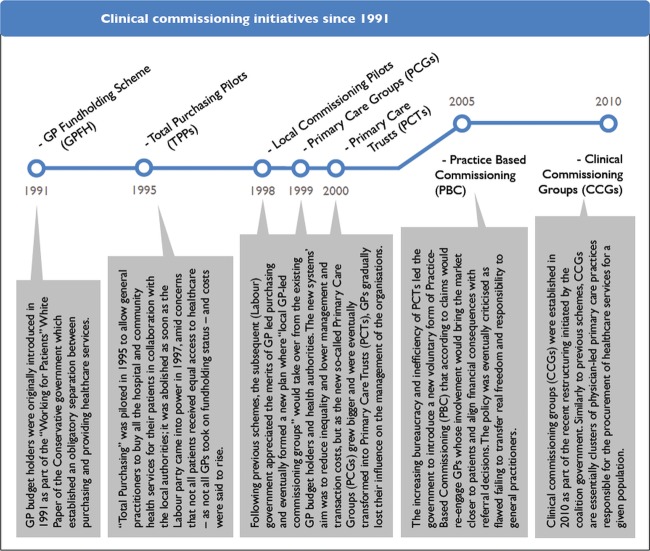

The success of clinical commissioning and its potential to deliver has long been discussed in health services research. In the past couple of decades, the government has endorsed and funded a number of alternative primary care-led purchasing schemes receiving mixed signals from clinicians, policy makers and the public. Figure 1 provides a timeline of clinical commissioning initiatives since 1991 when the internal market reform took place and the separation of purchasing and providing health services was introduced for the first time in the English NHS.8

Figure 1.

Clinical commissioning initiatives since 1991.

Overall, the different primary care-led commissioning models can be seen as part of a continuum of schemes available to use for purchasing healthcare services. Smith et al9 provide a scale of the different commissioning levels in the UK, whereby approaches vary from the individual patient level to a whole nation's population. As the different commissioning levels in the continuum respond to different policies, it is expected that there will be implications for the respective purchasing practices and for commissioners. More specifically, different approaches to commissioning will demand the involvement of actors across various levels and different locations. For example, GP fund holding was considered to be much more practice-led than practice-based commissioning (PBC) which involved groups of practices rather than individual practices.10 Alternative approaches will also lead to the formation of different clinical and healthcare networks as a response to meeting commissioning challenges within the health system and bringing together purchasers and providers.5

Drawing from the historical research evidence on commissioning organisations and their effectiveness, a number of implications emerge for the structure, governance and size of clinical networks. For example, small, high-density networks can ensure alignment of services with the local population needs but are often expensive. Overall, there has been a trade-off between lower levels of commissioning and transaction costs as the more local and smaller the network, the more expensive it is to maintain and deal with an increased number of purchasers. This issue was evident during the GP fund holding and total purchasing pilot (TPP) periods where the average size of the commissioning consortia was small and purchasing decisions were divided between several local commissioning organisations. Having said that, general practitioner fundholding scheme (GPFH) and TPPs were more effective in dealing with a more focused set of issues and managed to reduce waiting times for patients as well as achieve better collaboration between participating GPs.6 8 11 12 Their voluntary character, however, has created significant inequalities as those local networks that were engaged had a clear advantage over groups of GPs that were not involved.

In addition, as clinical networks aim to promote information exchange and understanding between physicians, local government, voluntary sector and so on and translate this discussion into innovative healthcare solutions for patients, GP leaders need to develop leadership (and commissioning) skills that will enable these relationships across multiple stakeholder groups.13 Rather than emphasising contracts and provider–purchaser negotiations, multiple stakeholders with different interests need to be integrated across an emerging network. Leadership activities in the new commissioning process emphasises on sharing knowledge and managing knowledge flows, collaborating with colleagues and external stakeholders and seeking advice from peers in different clusters.

Finally, incentives need to be embraced to motivate GPs and to influence their behaviour in their network. This can be achieved by facilitating autonomy and independence in being creative around contracting appropriate services.14 15 In the wake of CCGs, commissioning groups were much larger than previous clinical networksi and attempts were made to put financial incentives in place. In addition, clinical networks are primarily led by GPs who would be managing real budgets and will be required to join a commissioning group. Within this system of regulation and governance, clinical leaders will need to balance between managerial and professional interests, encourage collaboration and knowledge exchange and reduce boundaries between practitioners, institutions and other organisations.5

Table 1 provides a breakdown of the different primary care-led commissioning organisations and the implications for the healthcare networks that were developed.

Table 1.

Healthcare network implications of primary care-led commissioning organisations

| Coordinating mechanism | Key features | Governance and autonomy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Ham, Smith and Eastmure 2011; Ham 2008) | (Mannion 2011; Checkland, Coleman, Harrison et al 2009) | (Curry, Goodwin, Naylor, et al 2008; Smith and Goodwin 2002) | |

| General practitioner fundholding scheme (GPFH) | Market driven/emphasis on competition, strong procurement focus | Good for local commissioning and healthcare practice, local coherence Increased inequities |

No clinical governance, control of real budget, independent body |

| Total purchasing pilots (TPPs) | Market driven/emphasis on competition | Better integrated purchasing and provision Higher costs and risks |

No clinical governance, control of indicative budget, body within health authority |

| Primary care trust (PCTs) | Market driven/emphasis on competition, focus on administration of purchasing | Better control, budget allocation/management and economies of scale due to centralisation Less clinical input |

Statutory organisation, governed by PCT board (includes clinical input), own budget |

| Practice-based commissioning (PBC) | Market driven/emphasis on competition, transactions oriented | Increased engagement of clinicians Higher management and transaction costs |

Led by general practitioners (GPs), little clinical governance, indicative budget, voluntary scheme |

| Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) | Network-centric, trust, collaboration driven with emphasis on good communication, some degree of accountability | Potential to encourage innovation, best practice, higher quality, integration and cost-effectiveness of commissioned services High risk of network instability |

Clinical (GP) governance, real budget (2013), independent body, compulsory scheme |

Although network leadership that seeks to achieve collaboration and knowledge sharing is important in the commissioning process, research in this area has largely been focused on describing and comparing the different policies,6 8 by measuring resource allocation and economic outcomes.16 17 Our innovation network theory approach will explore GP-led commissioning by looking at knowledge mobility and collaborations in networks of clinicians, PCTs, patients, providers and other entities which play an important role in the development of novel commissioning arrangements and improved outcomes. We carried out research on six CCGs that examined the early function and emerging forms of CCGs; analysed how CCG leads orchestrate commissioning activities towards three key network leadership processes: managing knowledge flows, managing network coherence and managing network stability; identified strengths, issues and areas for development of the newly established CCGs; and contributed to the theoretical and methodological knowledge base in the study of clinical leadership in the context of commissioning practice.

Methods

This study is part of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) initiative, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which aims at supporting and translating research evidence into NHS practice. The study itself took place within NIHR CLAHRC for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and was facilitated by the collaborative partnerships between the University of Cambridge and surrounding NHS organisations.

Design and theoretical framework

We conducted a theoretically informed, mixed-methods case-study research across multiple CCG sites. While the responsibilities of the CCGs (initially known as GP commissioning consortia) are outlined in the recent government bill, very little is known about the organisational practices commissioners have adopted to develop novel local services. To fill that gap, the aim of the project is to understand the emerging role of CCG leaders and outline their coordination activities as leaders of their health network. In this process we chose to utilise innovation network theory for two reasons. First, the delivery of clinical commissioning and development of innovative services around it requires complex collaborations between a large number of stakeholders including patients and the public, local government and authorities, acute and other providers as well as front-line GPs, in the form of a value network. These so-called innovation networks are often characterised by loose, semitemporal linkages between actors who seek to employ the right resources and engage in strategic collaborations to deal with specific problems and develop innovative services and solutions.18 Second, this network-centric innovation model also recognises the need for a leading entity that will orchestrate the innovation activity within the network through a number of coordination processes19 20 thus emphasising the relationships that need to be established. Therefore, by mapping our findings on this theoretical framework we were able to identify various coordination processes that CCG leaders use. In addition, we are able to pinpoint particular strengths, issues and areas for further development of CCGs and identify key leadership skills that will help GP leads manage their network in the future.

Sampling

During our fieldwork we conducted an in-depth and systematic study of six CCGs and local clusters (also called localities) in the East of England region (sites A, B, C, D, E and F). These groups covered mixed patient populations varying between 50 000 and 550 000 patients. In total, our sample groups covered 1 662 000 patients served by 208 GPs. The number of board members of the CCGs also varied according to the size of the population they covered with the smallest numbering four members and the largest being 14. The total number of board members of all six commissioning groups at the time of data collection was 63.

The first wave of GP commissioning consortia took place in December 2010 and introduced 52 ‘pathfinders’ initially covering 12.9 m people. Second, third and fourth waves followed soon after and by the end of April 2011 GP commissioning covered 9 of 10 people in England.ii Most of the groups in our sample were given pathfinder status during the first two waves. Table 2 presents all the main characteristics of our CCGs and localities sample, and points to the variability of network structure. The size variation in our sample is similar to that in the national statistics of the first two waves (numbering 137 consortia): the average population covered per CCG was approximately 207 000 with a standard deviation of 146 000 (minimum 14 000/maximum 693 000), and the average number of practices under a CCG was 30 with a standard deviation of 22 (minimum 1/maximum 105).

Table 2.

Main characteristics of CCGs and localities sample

| Status | Pathfinder wave | Covering |

Localities (clusters) | Board representation |

Executive support | PBC roots | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Practices | Secondary care | Nurse | Patient | ||||||

| Site A | CCG | 1 | 300 000 | 30 | 6 | N | N | Y | N | None |

| Site B | CCG | 2 | 550 000 | 60 | 4 | N | N | Y | N | Strong |

| Site C | Locality | – | 50 000 | 4 | – | N | N | N | N | Weak |

| Site D | CCG | 2 | 325 000 | 47 | 2 | N | Y | N | Y | Strong |

| Site E | CCG | 1 | 230 000 | 27 | 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Medium |

| Site F | CCG | 1 | 77 000 | 10 | – | N | Y | Y | Y | Strong |

Data collection and analysis

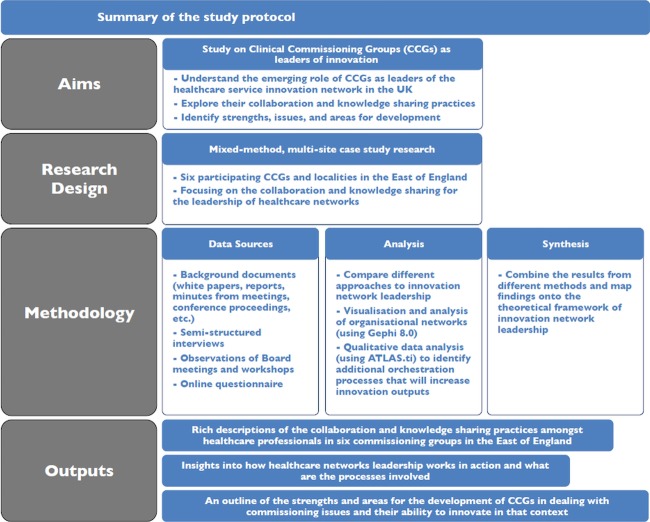

Access and pilot interviews were initiated in November 2010 and the main data collection took place between February and December 2011. During that time commissioning groups were in a preliminary pathfinder stage and did not have any fund holding rights or statutory powers. In addition, at that time there was no official guidance from the Department of Health other than the initial bill and supplementary information on commissioning. However, nearly all CCGs we examined had established formal operating procedures that allowed them to function as organisations with particular membership and board structure. In total 56 healthcare professionals were interviewed: 35 board members (mostly GPs but also PCT employees and practice managers) plus an additional 21 people from various organisations including acute provider representatives and health authorities executives. In addition, we observed 21 CCG board meetings and executive committees within local clusters. This helped us to witness how these groups work in action rather than rely solely on the espoused views of their members. We kept field notes during meetings and transcribed all interviews after recording (apart from few exceptions). We used ATLAS.ti to categorise, code and analyse qualitative data including hundreds of pages of background documents such as national-level policy reports, minutes from meetings and speech transcripts from conferences and workshops (table 3) (figure 3).

Table 3.

Breakdown of interviews, observations and survey response by site and type

| GPs | PCT employees | Practice managers | Hospital | Other | Total | Meeting observations | Number of board members | Survey participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site A | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 13 | 100% (13/13) |

| Site B | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 13 | 92% (12/13) |

| Site C | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 100% (4/4) |

| Site D | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 92% (12/13) |

| Site E | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 14 | 93% (13/14) |

| Site F | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 83% (5/6) |

| Total | 21 | 13 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 56 | 21 | 63 | 94% (59/63) |

Figure 3.

Summary of the study protocol.

Having CCG board members as our unit of analysis helped us to confine our research and also limit our study of their healthcare innovation network to their immediate contacts. Moreover, GP leaders as main stakeholders also assisted us in identifying potential targets to question. Additional interviewees were also recognised through the observation of board meetings with the intention of getting a variety of perspectives and evidence. Interviews usually lasted between 35 and 90 min and were conducted either by phone or in person. We compared organisational forms and leadership routines across the six groups and highlighted their variations. Key themes that emerged from the interviews were coded according to the coordination processes with which they were related. Based on network leadership theory, three innovation network leadership routines were identified as relevant with our CCG study: managing knowledge flows, managing network coherence and managing network stability.

In order to provide external validity to our research results, and debate whether the theoretical approach we have used could be useful for the future development of CCGs nation-wide, we presented our findings to a number of CCG board of directors and (particularly to those who were interested in the feedback) at a regional event on clinical commissioning where most of the commissioning groups were represented.

Social network analysis

In addition to interviews, CCG documentation and other publications, we also collected responses using an electronic survey on knowledge sharing and collaboration practices which were emailed to all board members of the CCGs we studied. The response rate for this was approximately 94%iii and the results helped us identify knowledge exchange patterns among board members and outside parties regarding clinical commissioning. We used social network analysis (SNA) to discern the popularity of certain individuals in the network and the individuals that board members go to in order to acquire advice regarding commissioning issues. More specifically, we were able to measure the number of ties the CCG board members have (also called ‘degree’) as well as their centrality into the network (also known as ‘betweenness centrality’) to understand which members act as brokers and have the ability to transfer knowledge from other parts of the healthcare network and across CCGs. Finally, we calculated the density of the CCGs which measures the extent to which board members are interrelated and go to their colleagues for advice. This measure indicates in someway the good communication and team-working activities among CCG members.

The visualisation and analysis of the CCG board networks were performed using Gephi 8.0.

Results

Commissioning context: the challenges of network leadership

The current commissioning context presents a number of challenges for leaders in establishing innovation networks. In the following analysis, we examine the dynamics of multiple relationships which CCG leaders needed to establish to facilitate commissioning across their health networks, and in particular the need to enable knowledge exchange, network coherence and network stability as dynamic capabilities that support innovation networks. We consider the CCG board relationship with PCTs, health providers and service users, frontline GPs and the broader health polity. We conclude our analysis by comparing two innovative developments in CCG board commissioning practices in the sites studied, using them as illustrative rather than exemplars.

Establishing relationships with PCTs

There were variations in viewpoints among the CCG leaders at the six sites as to the way relationships with PCTs were managed. Leaders in some sites worked well with PCTs describing the relationship as cooperative and being ‘open’ and ‘supportive’, ‘getting better at seeing each other's point of view’. Some CCG leaders viewed PCT employees as a useful source of information and commissioning expertise. A CCG board member at site B pointed out: ‘I see my role as coordinating, having some ideas and then asking PCT people to develop those ideas. There’re only so many hours in a week and I can't do everything, so I draw on the skilled people at the PCT’. At site C whereby leaders developed a novel and collaborative arrangement whereby GPs and PCT managers were paired together to form a PCT sub-committee to resolve commissioning issues. These examples reveal the important role many PCT staff played as knowledge brokers who facilitated knowledge sharing and transfer across the network.

At the same time, however, GP leaders were acutely aware of the perceived limitations of the knowledge held by PCTs in commissioning. It was generally understood by CCG board members that PCTs were ‘being abolished [because they] haven't delivered what [they] should have done” (site B). A GP in site A was similarly critical pointing out that: “the contracting has been poor and it hasn't been adequately informed […] it is basically a legacy […] There wasn't actually any thinking or decision making’. Thus leaders were wary of adopting the knowledge and ideas of PCT commissioning practices.

A similar dilemma was faced by the PCT staff. On the one hand they recognised that ‘you've got the PCT trying to offload its activities to the CCGs’, in a supportive manner. On the other hand, a number of PCT employees felt threatened by CCG formation and were highly aware of their own job insecurity. As a result PCT members were not always willing to openly cooperate with CCG leaders, for example restricting funding of new commissioning arrangements. A GP described how the indifference of PCT employees towards the success of the CCG led to frustration in his board. There was a perceived view that a ‘not invented syndrome’ limited the potential for innovation; ‘nobody got the idea and they just refused to fund it’ (site C). The wavering support of PCTs stemming from the uncertainty of their future contributed to instability across the health network. There was also system-wide concern as to who would be responsible for the essential non-commissioning tasks currently being done by PCTs, and how they would be undertaken in the new health system. This hindered the development of trust and commitment as a critical basis for collaborative relationships with CCG board members.

Co-location arrangements further constrained (or enabled) communication between CCG members and PCT employees, leading to misinterpretations and delays in the transfer of information and data. One PCT director (site D) felt that their good relationship with GP leaders ‘was due to geography […] we brought the PBC support unit into the PCT building so they are in the same place as us […] sitting side-by-side with the PCT staff […Now with CCGs] that absolutely helped’. In our research sample, sites that had supportive relations between respective PCTs and CCGs used the PCT premises to hold their board meetings. In networks where CCGs were detached from PCTs, the board meetings were held elsewhere (eg, in sites B and E). These results are reflected by the social network analysis (see comparison between sites A and B in table 4).

Table 4.

Site A and site B network ties

| GP practices | PCT (Local health administration) | Acute providers | Regional NHS (SHA) | Community providers | Local authorities | Other ties | Total ties | Board density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site A | 3 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 0.737 |

| Site B | 6 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 36 | 0.622 |

Relating to providers and users

As discussed later on in our vignettes, a critical CCG leadership task is embedding relationships with health providers within the commissioning network, integrating secondary care provision with primary care in novel ways. A CCG board member suggested: “We need to get that relationship (commissioner-provider) off from a good start […] to sort a strategy that is going to pull them (providers) in from the beginning [and realise] that it's not ‘take all our money and continue to deliver as you've always done’. We've got to do things differently” (site B). Establishing trust and adequate knowledge exchange between CCG and provider entities remained an on-going challenge.

See online supplementary box 1 highlights multiple instances from our analysis regarding the importance of knowledge exchange and collaboration in enabling service integration across primary and secondary care structures.

Further, our results from the SNA analysis showed that there was generally a substantial lack of communication between CCGs and acute providers. In our CCG network sample, boards had a maximum of three ties with acute providers; this is very low when considering that these relationships are at the core of clinical commissioning and central to all the sample local innovations, including those summarised in the vignettes.

Another important network dynamic between CCG boards and healthcare providers related to knowledge sharing around appropriate level and type of costing data relevant to commissioning. This lack of information often described as ‘a black box’ around the services being provided and their associated costs leads to challenges of network level coherence of information to support innovation. A GP board member at site C explained, “we have actually no idea what the costs are of these pathways…it is very difficult to get any data or real information from [the acute provider]…they haven't had to share this before we can't commission [properly] without it.” Another GP board member reinforced that even in their own medical practice it was difficult to manage patients’ care in a way that optimised commissioning efficiency; ‘When I sign the referral letter I commission the spending of that money, but effectively what I'm doing is signing a blank cheque because I have no idea what the cost will be as the patient goes down that pathway. And if say there were two competing providers … which of those two pathways would be better to use and what are the costs and the outcomes of the two pathways, well I don't have that information’. As discussed later in the vignettes, comparative information and data analysis were important initial drivers of the innovation process. The tension between GP commissioners and secondary care specialists is described by a PCT employee as a conflict of interest where ‘providers want to maximise their income while [commissioners] want to maximise efficiency’ (site B).

In addition to providers, users constituted another important stakeholder that contributed knowledge towards the commissioning process. Over half of the CCGs had a patient representative on their board (sites A, B, E and F) to improve the final service offering. One of the patient representatives interviewed felt that he made ‘direct input’ into the board meetings, and felt that he made an important contribution as ‘any service user knows what it's like on the other side, to be on the receiving end. They can give very practical suggestions about what works, what doesn't, what are glitches in the system’ (patient representative, site A).

However, there was voiced confusion among leaders regarding how experiential knowledge from service users should be used and incorporated into the wider, population-level commissioning agenda of CCGs. A GP leader (site C) highlighted it was a challenge to engage patient groups into providing inputs at the locality and or CCG level: ‘Patients are not usually interested in it’, ‘they are busy and do not want to do things like this’ (site B), ‘patients will only be involved if there is money to be made’ (site A). In addition, many GPs commented that when inviting patients to provide feedback ‘you get half a dozen […] with particular reason or agenda’, suggesting this form of engagement did not lead to constructive dialogue on improving patient care. A GP from site B pointed out: ‘I think they [patients] are just there representing their own views as they see it’. Even though the wider perception from policy documents on public and patient involvement in commissioning was that patient views were valuable, there was no mechanism in place to operationalise lay representation and overall it was often carried out in a piecemeal fashion. For example, in some of the locality meetings we observed, individuals who had the flexibility to attend were listening attentively to discussions without engaging in overt dialogue. In other meetings, there was a set time given to patient representatives to present their perspectives. As such, several GP leaders felt that in the current fiscal climate and organisational upheaval, investing scarce resources in organising patient groups and their input was questionable, revealing the challenge in genuine public or patient representation.21

Engaging with frontline GPs

In order for commissioning decisions to reflect the corpus of primary care views across the network, CCG leaders need to find mechanisms for knowledge exchange with frontline clinicians. As shown though both case vignettes of innovations uncovered within our sample CCGs, novel ways of delivering a service or new services entailed commitment and engagement of frontline GPs, both in providing the new ideas and also enrolling colleagues in the new practice. Enabling knowledge flows across the network also enables the development of innovative ideas. Engagement and nurtured relationships with frontline GPs helps ensure that the knowledge held by these members is made available across the network, contributes to new practices and guides the leaders’ decision making.

Yet the ability to engage with front line GPs is related to the CCG size; smaller networks can more easily be densely connected, as it is easier to maintain ties with a smaller number of individuals. Network size in our context, is directly related to the proportion of population covered as government payments follow the patients. In the commissioning context, larger networks create a more stable environment (ie, network stability) as risk (in particular for financial failure) can be spread across the whole network. This more stable position also improves the leaders’ ability to negotiate, owing to their increased purchasing power across the network. “There's this sense that we have to be big in order to have the clout to negotiate” (site B). However, as network size increases, it becomes more difficult for leaders to engage with frontline members. Thus leaders also kept stressing that ‘if they [completely] ignore the size issue, they will fail to get [GPs] engaged and on board’ (site B), thus, highlighting the difficulty of engaging frontline GPs in clinical commissioning.

To manage the concern of maintaining a necessary network size, several sites developed smaller localities, clusters of practices within their network which resolve local issues, including commissioning. The localities’ leaders are typically part of the CCG board, responsible for leading the overall commissioning process. A GP commented, ‘[frontline engagement] won't work at three hundred thousand [patients] level […therefore] having those sub-groups, those cluster level groups is vitally important’ (site C). CCGs structure reflects the tension in achieving strong local commitment and efficiency through scale (see table 2 for a summary of the range in population size across study CCGs).

An important contextual feature that shaped the network size and its membership ties was the commissioning history, in particular, the legacy of PBC. Even though PBCs never held actual commissioning funds throughout their existence, they had established a distinctive ‘organisational archetype’22 which itself was a result of the sedimentation that took place during the organisational changes of the reform at that time. By and large, the specifications of the previous organisational archetype (in this case PBC groups) has an apparent effect on network formation and knowledge capability. In the reform process, change ‘represents not so much a shift from one archetype [PBC] to another [CCG], but a layering of one archetype on another’ (ref. 22, p.624), so that the new entity embodies the interlacing of previous structures and relationships with novel network features. As highlighted in our analysis of the vignettes around innovation between one former PBC and a non-PBC group, legacy ties between stakeholders influenced the innovation process.

CCG relationship with policy and administrative authorities

Another significant relationship influencing the new commissioning scheme is the relationship between GPs and health policy makers and administrators who oversee the implementation of the policy. Numerous GP leaders expressed frustration that a number of their colleagues are hesitant to engage because of the perceived weak engagement and lack of dialogue between policy makers (or their representatives) and CCG leaders. On the whole communication is seen as a one way process. During the course of the study we observed an increasing frustration among the CCG leaders. Several of them who were enthusiastic and motivated early on started to believe that their efforts were misplaced: ‘it was clear that there were many unfinished episodes and contradictions in the legislation, the Minister then turned to the professions in order to get their input and called those pathfinder organisations’. A GP from site A mentioned: ‘I was happy to contribute as a pathfinder under those terms but the pathfinders (forerunners of policy implementation) were used as evidence that the profession supported the Bill […] then I felt that I'd been tricked into being a pathfinder’.

As a result, numerous frontline GPs and CCG leaders commented they were becoming increasingly cynical and started questioning their engagement in CCG activities: ‘We're in between at the moment, waiting to know what the new world is going to look like, and not really being able to get on with things until that's clear’ (site A). In parallel with the uncertainty around the future of the reform contributing to network stability, CCG leaders felt that they have little guidance from the policy makers regarding their new activities and responsibilities: ‘the government is being less than explicit’. Yet at the same time CCG leaders did not feel able to shape the strategic direction nor develop new rules for the commissioning process, and this uncertainty was compounded by the simultaneous restructuring of PCTs.

Relational dynamics of early stage innovation in two CCG networks

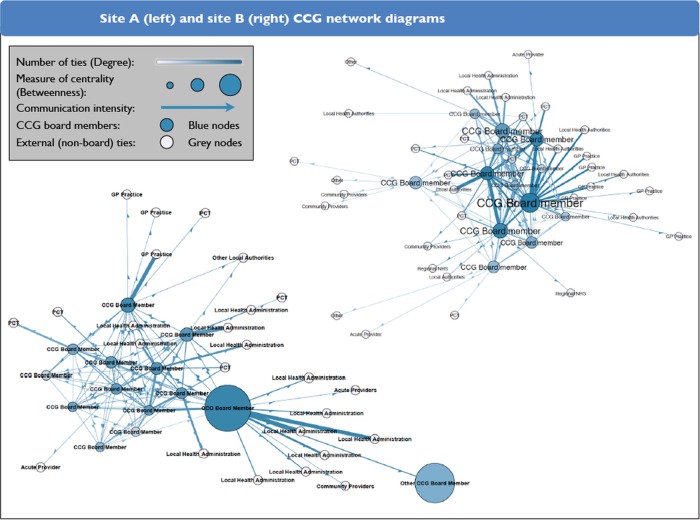

In the vignettes below (see online supplementary boxes 2 and 3), we compare two interesting examples as to how relational dynamics in nascent CCG networks surrounding site A and site B enabled (and constrained) early stage innovation. We develop our insights concerning the relational dynamics drawing on the social network data (figure 4 and table 4) and the leadership challenges of working across the multiple stakeholders involved.

Figure 4.

Site A (left) and site B (right) clinical commissioning group network diagrams.

In site A, where CCG leaders had access to comparative data from across the health system, the board leaders drew on existing strong relationships with the PCT to develop a solution in the form of joint working groups within the specialist areas and pathways of concern. The stimulus for the innovation process came from the available data highlighting the importance of network (in)coherence, coupled with the numerous ties with the PCT. As can be seen from table 4 the social network analysis comparatively illustrates the numerous ties among the CCG board and local health administration entities (PCT) in site A (18) which is higher than site B (13). The strong ties with the PCT was crucial in bringing together the other critical stakeholders (eg, acute providers) as the CCG board, had established ties with other stakeholders. In addition, the density of the ties across the board itself (0.737) indicates a high level of knowledge sharing and cohesion among the CCG leaders. This facilitated centrally coordinated action to develop the multiple pathway groups.

The social network diagram in figure 4 illustrates the relatively uniform communication pattern across the board; it also brings to fore the very heavy reliance on a single knowledge broker (large blue node with high degree and betweenness centrality in site A). Overreliance on a small number of knowledge brokers adds risk to the network, for example in the case where the individual should exit the network. The network also becomes dependent on a few individuals who are able to commit a considerable amount of time for developing leadership processes.

Innovation emerged in site B from a frontline GP who recognised incoherence in one area of the network, given her knowledge of local primary-based care and specialist care. The board in site B is characterised by high levels of front-line GP engagement, illustrated both by the high numbers of direct ties to the board (6) and also the communication intensity between those ties, with relatively thicker blue lines in the social network diagram between board members and GP practices, as compared to site A. This enabled the innovation to be embedded and taken up by the GP community. However, as evidenced by the lower density of ties between CCG board members (0.622) there was an element of competition between the CCG leaders who represented the former PBC groups, indicated as the larger blue circles in the social network diagram (site B graph on the right of figure 4). This influenced the integration and coordination of practices across the network as a whole, and hampered the scaling up of the innovative practice to other regions within the network.

In both cases, the development of novel care pathways arose from information regarding network incoherence, and a realisation that local care was out of alignment with care being provided in equivalent regions elsewhere. There was also a reliance on engaged frontline GPs and the use of strategically reconfigured knowledge flows to facilitate the development and delivery of a new service. Across the innovations new practices were knitted together from new relationships at multiple levels; structuring knowledge in new ways enabled novel insight as to how services could be integrated. Acting as relational catalysts rather than necessarily involving themselves in all relationship building, clinical leaders facilitated network coherence, stability and knowledge sharing in enabling innovations to emerge.

Discussion

In this study we have shown the importance of understanding and developing a network-centric approach to clinical commissioning and the need for network leadership to facilitate integrated care and provide innovative, patient-centred healthcare solutions. A critical part of the new role of GP leaders is to enable coordination and new relationships across the health network. Our study suggests that they need to go beyond focusing on transactions and bilateral relationships to fostering knowledge sharing with multiple stakeholders, while ensuring network stability and coherence. In addition to establishing a number of brokering ties themselves, leaders need to strategically enable adequate inter connectivity across the wider system acting like a relational catalyst.

Characteristics of clinical commissioning networks

Recent research and reviews have shown that commissioning arrangements have suffered from increasing fragmentation,6 hampered communication across primary and secondary care, challenged integration of purchaser and provider interests,23 high transaction costs8 and unresponsive secondary care provision.8 However, they do not have to focus only on the procurement and administrative aspects of commissioning.

We see the evolving clinical commissioning networks as falling within the characterisation of innovation networks,19 whereby the coordination of network activities are usually performed by key entities. The newly established CCGs act as innovation hubs ensuring that information and knowledge are circulated around the network to establish collaborations and warrant the creation and extraction of value.20 Just as with any other research of healthcare networks, clinical commissioning networks have the potential to generate multidisciplinary coalitions7 between GPs, acute providers, local authorities and other key healthcare professionals to agree upon the services to be purchased. This network-centric approach can allow CCGs to revisit the existing clinical pathways and develop new integrated, patient-centred healthcare solutions by leveraging the structural characteristics of their network—expansive, decentralised, open, less hierarchical, thereby providing increased flexibility and encouraging knowledge brokering.5

Network leadership and practice implications

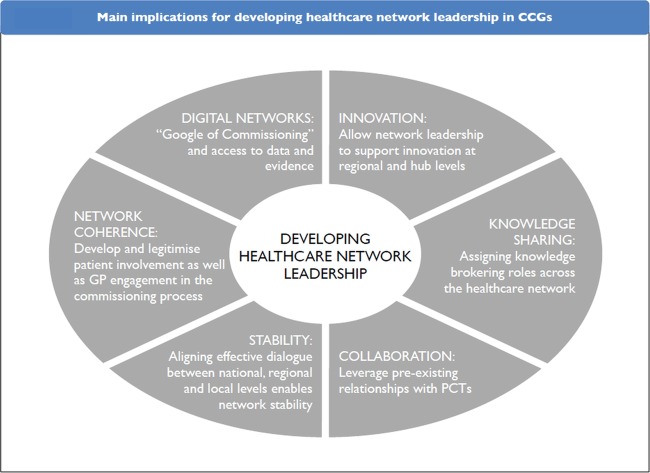

A new breed of clinical leaders is required that would coordinate innovative activity and ensure healthcare service delivery through collaborative and teamwork efforts in the broader healthcare network.24 Current understanding of enabling innovation networks points to the importance of knowledge exchange, network stability and network coherence in achieving ecosystem outcomes (figure 5).19 20 CCG leaders are required to provide ‘subtle leadership’,25 focusing on visioning, motivating and sense-making, rather than controlling.26 Having said that, such delegative leadership from one hand can enhance social autonomy and boost innovative outcomes but on the other hand it may be challenged to drive knowledge integration.27 In the absence of strict hierarchies, these leaders need to develop brokering strategies that will not only facilitate links between stakeholders but will also couple healthcare professionals to deliver outcomes. For example, it is necessary to adopt ‘soft’ strategies that will inspire people and engage grass root GPs but might also need to provide ‘hard’ incentives that will motivate people to commit to quality service and cost reduction. We suggest that these skills are important to re-emphasise given the historical commissioning focus on planning, monitoring and assessing.

Figure 5.

Main implications for developing healthcare network leadership in clinical commissioning group.

CCGs need to encourage knowledge exchange and collaboration

Perhaps one of the most significant leadership practices of CCGs as innovation hubs should be to manage the flow of information and knowledge sharing across their clinical commissioning network. Such coordination of knowledge mobility can allow to direct efforts that will lead to strategic collaborations and synergies between commissioners, healthcare providers and other key parties such as local organisations and authorities. Expansive and open networks allow for more information to travel from ‘distant’ members through knowledge brokers who will introduce new ideas. In turn, good interconnectedness and high-density at the CCG board level can help operationalise these ideas and translate them to actual services. In relation to frontline GPs in particular, clinical CCG leaders are in a position to relate to them at a collegial level, relating to their priorities and practice dynamics; replacing this relational focus with a mind-set that emphasises tasks to be accomplished will more likely stymie engagement and innovation instead of helping.

Efforts need to be aligned with patient needs and medical developments

In addition, GPs as network leaders must not only generally encourage more involvement of PCTs, local authorities and providers in designing cost-effective and quality pathways, but will also need to streamline the patients’ feedback and find a consistent and structured way to capture and take into account their views. Both these ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ strategies for network leadership are imperative in facilitating the development of new clinical practices and novel commissioning ideas. CCGs are in a good position to implement these as they are trying to establish a new organisational form and leadership style that will fit the current culture which does not adhere to directive leadership, but encourages a delegative approach.

Further, external network coherence goes beyond the patients’ perspective. It is also necessary to follow medical and research developments, technological advancements, as well as international trends and to benchmark these with the practices and clinical decisions made locally. To manage coherence at this external level, leaders need to draw knowledge in through clinical, research and public health networks in a systematic way.7

Develop incentives and accountability for network stability

Network stability is imperative in any organisational context, so a critical leadership task for network leaders is to promote it at any cost.19 The risk to unstable innovation networks is inherent owing to their flexible less-hierarchical nature, which is necessary to encourage innovative activities based on ad hoc collaborations between different parties in the healthcare ecosystem. In that sense there is a trade-off between ordered relationships (that are forced from top down) and loosely coupled interactions that emerge from the personal incentives of the collaborators. However, excessive erosion of network relationships can lead to a state of instability, thereby reducing the value and innovation output of the network.28

In this context, clear financial incentives and transparent accountability mechanisms have the ability to prevent discouragement and distrust in the network. GP leads and the concerned polity need to keep network members motivated to engage with the commissioning activities and be encouraged to share their ideas and knowledge and establish collaborations with other parties. In addition, some degree of accountability that will be open, transparent and comprehensible to everyone needs to be in place to manage risk and sharing of the rewards and value. These activities motivate members and will sustain their efforts while contributing towards the stability of the overall commissioning network (box 1).

Box 1. Summary of emerging key policy recommendations.

Overall network leadership strategy

GPs need to realise their new role not only as clinicians but also as coordinators that will lead the healthcare network in both a delegative and directive manner.

Build a strategy around clinical commissioning that will include not only developing collaborative relationships and knowledge sharing with PCTs and local authorities but also the inputs of patients and the public (healthcare ecosystem).

The CCG board should develop 'soft' strategies that will inspire and engage front-line GPs at the grass roots level and provide 'hard' incentives that will motivate people to commit to quality service and cost-effectiveness. Implementation of such a strategy should include a system of measurement and accountability.

Integration of primary and secondary healthcare activities which delivers not only a more cost-effective service, but crucially ensures a patient-centric pathway service too.

Managing knowledge mobility

Identify well-connected individuals who maintain extensive advice and knowledge-sharing networks. Because of their connectedness, knowledge brokers in the network are expected to bring novel information to the group as they have access to a lot of people outside their cluster, potentially allowing for better commissioning decisions.

Considering the importance of the brokers (who may be clinicians, practice managers or PCT directors) in circulating knowledge, it may be justified to develop personal coaching and training sessions to improve individual brokering performance.

Developing digital networks and technological infrastructure can play a key role in disseminating best clinical practice and valuable knowledge by creating large integrated information repositories where commissioners will be able to access the necessary intelligence and evidence to support their work.

Apart from knowledge circulation that encourages healthcare service innovation, GPs will also need to translate and integrate this knowledge into their commissioning practice.

Managing network coherence

CCGs need to streamline the patients' feedback and find a consistent and structured way to capture and take into account their views.

Following medical and research developments, technological advancements, as well as international trends, will help benchmark and increase the quality of clinical decisions made locally.

Managing network stability

Establish a transparent clinical commissioning vision and values that will promote trust and collaboration among GPs and other healthcare professionals. This will also indirectly promote knowledge mobility and network coherence.

Health policy and leaders need to provide clear incentives as well as evident accountability mechanisms to establish trust and prevent discouragement.

Conclusions

In conclusion, clinical commissioning leaders can play a critical role in the coordination of healthcare innovation networks through a number of processes which include managing: knowledge flows, network coherence and network stability. Building relational capabilities in a delegative and directed manner is an important leadership issue for CCGs in establishing and expanding their networks with local health administration, NHS providers and other stakholders. To achieve this they will need to assign and exploit knowledge-brokering roles and leverage good communication between their board members and others outside their board to bring new ideas into the group, facilitate new synergies and alliances, and allow for projects that take advantage of the available resources. In addition, they need to identify and assess pre-existing relationships, which have institutional influences on them (eg, PBC groups), that they can capitalise upon while incorporating the views of local stakeholders as well as patient and public voice in a systematic way. Finally, technology can play a key role in disseminating practices and knowledge by creating integrated information repositories where commissioners will be able to access the necessary intelligence and evidence to support their work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the board members of the clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) for their participation as well as the rest of healthcare professionals that agreed to be interviewed for this project. The authors would also like to thank Celine Miani for her help on data collection and for providing administrative aid during the research project.

Contributors: EO and MB contributed to the research proposal, applied for the CLAHRC grant, and conceptualised the study. MZ, EO and MB completed the data collection. All authors contributed to the analysis of the data, the writing and revising of the paper. EO is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded by a research grant from the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) initiative, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The funders were not involved in the selection or analysis of data, or in contributing to the content of the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

The median population covered by the 212 CCGs so far preparing for authorization is 226 000.

Statistics as well as interactive maps on GP commissioning consortia can be found online at: www.gponline.co.uk.

Out of the 63 board members who received the electronic survey 59 replied. Two of the four people who did not respond were new board members.

References

- 1.Department of Health Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS,London, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health Practice based commissioning: technical guidance, London, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams D. Under Doctors’ orders. Public Finance 2010;August

- 4.Woodin J, Wade E. Towards World Class Commissioning Competency, Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin N. Are networks the answer to achieving integrated care? J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:58–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mays N, Goodwin N, Bevan G, et al. General practice what is total purchasing? BMJ 1997;315:7109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas P, Griffiths F, Kai J, et al. Primary care networks for research in primary health care. BMJ 2001;322:588–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannion R. General practitioner-led commissioning in the NHS: progress, prospects and pitfalls. Br Med Bull 2011;97:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith J, Mays N, Dixon J, et al. A review of the effectiveness of primary care-led commissioning and its place in the NHS. London, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman A, Checkland K, Harrison S, et al. Local histories and local sensemaking: a case of policy implementation in the English National Health Service. Policy Polit 2010;38:289–306 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowling B. GPs and purchasing in the NHS. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J, Goodwin N. Towards managed primary care: the role and experience of primary care organisations. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood J, Curry N. PBC two years on: moving forward and making a difference? London, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry N, Goodwin N, Naylor C, et al. Practice-based commissioning: reinvigorate, replace or abandon? London: The King's Fund, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith J, Curry N. Commissioning. In: Mays N, Dixon A, Jones L, eds. Understanding New Labour's market reforms of the English NHS. London: The King's Fund, 2011:30–51 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon J, Smith P, Gravelle H, et al. A person based formula for allocating commissioning funds to general practices in England: development of a statistical model. BMJ 2011;343:6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hine CE, Bachmann MO. What does locality commissioning in Avon offer? Retrospective descriptive evaluation. BMJ 1997;314:1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Wijk R, Van Den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW. Knowledge and networks. In: Easterby-Smith M, Lyles MA, eds. The Blackwell handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2003:429–53 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhanaraj C, Parkhe A. Orchestrating innovation networks. Acad Manage Rev 2006;31:659–69 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nambisan S, Sawhney M. Orchestration processes in network-centric innovation: evidence from the field. Acad Manage Perspect 2011;25:40–57 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin GP. Whose health, whose care, whose say? Some comments on public involvement in new NHS commissioning arrangements. Crit Public Health 2009;19:123–32 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper DJ, Hinings B, Greenwood R, et al. Sedimentation and transformation in organizational change: the case of Canadian law firms. Organization Stud 1996;17:623–47 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ham C, Smith J, Eastmure E. Commissioning integrated care in a liberated NHS. London: The Nuffield Trust, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TH. Turning doctors into leaders. Harv Bus Rev 2010:50–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orton JD, Weick KE. Loosely coupled systems: a reconceptualization. Acad Manage Rev 1990;15:203–23 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ancona D, Malone TW, Orlikowski WJ, et al. In praise of the incomplete leader. Harv Bus Rev 2007;February:1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebert D, Boerner S, Kearney E. Fostering team innovation: why is it important to combine opposing action strategies? Organization Sci 2009;21:593–608 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenzoni G, Lipparini A. The leveraging of interfirm relationships as a distinctive organizational capability: A longitudinal study. Strateg Manage J 1999;20:317–38 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.