Abstract

Objectives

A growing body of evidence suggests that there is a relationship between impaired lung function and the risk of developing diabetes mellitus (DM). However, it is not known if this reflects a causal effect of lung function on glucose metabolism. To clarify the relationship between lung function and the development of DM, we examined the incidence of newly diagnosed prediabetes (a precursor of DM) among subjects with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) at baseline.

Design

Primary analysis of an occupational cohort with both cross-sectional and longitudinal data (follow-up duration mean±SD: 28.4±6.1 months).

Setting and participants

Data were analysed from 1058 men in a cross-sectional study and from 560 men with NGT in a longitudinal study.

Outcomes and methods

Impaired lung function (per cent predicted value of forced vital capacity (%FVC) or per cent value of forced expiratory volume 1 s/FVC (FEV1/FVC ratio)) in relation to the ratio of prediabetes or DM in a cross-sectional study and development of new prediabetes in a longitudinal study. NGT, prediabetes including impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and increased fasting glucose (IFG) and DM were diagnosed according to 75 g oral glucose tolerance tests.

Measurements and main results

%FVC at baseline, but not FEV1/FVC ratio at baseline, was significantly associated with the incidences of DM and prediabetes. Among prediabetes, IGT but not IFG was associated with %FVC. During follow-up, 102 subjects developed prediabetes among those with NGT. A low %FVC, but not FEV1/FVC ratio, was predictive of an increased risk for development of IGT, but not of IFG.

Conclusions

Low lung volume is associated with an increased risk for the development of prediabetes, especially IGT, in Japanese men. Although there is published evidence for an association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and DM, prediabetes is not associated with the early stage of COPD.

Keywords: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Impaired Glucose Tolerance, Increased Fasting Glucose, Prediabetes, Pulmonary Function

Article summary.

Article focus

We hypothesised that lung function is associated with the development of impaired glucose metabolism. To investigate this, the data of an occupational cohort were analysed from 1058 men in a cross-sectional study and from 560 men with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) in a longitudinal study.

Key messages

Low lung volume was significantly associated with the incidence of prediabetes or diabetes mellitus (DM) in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.

Low lung volume is an independent risk factor for a particular type of prediabetes, impaired glucose tolerance rather than impaired fasting glucose. Our results suggested that prediabetes is not associated with the early stage of COPD, although there are published evidences for an association between COPD and DM.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study that prospectively examined the incidence of newly diagnosed prediabetes among subjects with NGT at baseline. There are several limitations including that the subjects were limited to Japanese men and our occupational cohort may possibly be healthier than the general population.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that there is a close relationship between impaired lung function and diabetes mellitus (DM). Population-based studies have demonstrated associations between both obstructive and restrictive lung impairment and insulin resistance or DM.1–9 A representative obstructive lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is now well known to be associated with a variety of comorbidities, including DM.10–13 However, an accelerated decline of lung function has been observed in patients with DM.14 The incidence rates of COPD, asthma, lung fibrosis and pneumonia are greater in patients with DM than in those without DM.15 The incidence of death from COPD is also increased in DM.16

The metabolic stage between normal glucose homeostasis and DM is called prediabetes, which the WHO divides into impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and increased fasting glucose (IFG).17 Both IFG and IGT are the established risk factors for DM.18 The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group15 found that about 30% of subjects with prediabetes developed DM during 3–5 years of follow-up. IFG and IGT are also risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), relationships that are not confounded by the development of DM.19 20 Subjects with prediabetes also have higher incidence rates of microvascular complications, including neuropathy, retinopathy and nephropathy, than do those with normal glucose tolerance (NGT).21 22

We reported previously that smokers with airflow limitation had subclinical atherosclerosis as evidenced by carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT).12 Although we excluded subjects with DM, the prediabetic state may influence the association, since prediabetes per se was accompanied by a modest but significant increase in the risk for developing CVD, as described above. However, there is no information regarding the association between lung function and prediabetes. Therefore, we explored the incidence of newly diagnosed prediabetes among selected subjects with NGT to further elucidate the nature of the relationship between lung function and the development of DM.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects were recruited from 1218 men who attended the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone West Corporation Chugoku Health Administration Center for general health checkups between April 1999 and March 2006. One hundred and sixty subjects were excluded, because they did not meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) between 40 and 59 years of age at the first examination, and able to perform both a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and adequate spirometric measurements (146 subjects excluded); (2) no known respiratory disease (14 excluded). Data from the remaining 1058 subjects were used for a baseline cross-sectional analysis. For the longitudinal study, subjects were restricted to those who had NGT (365 excluded), and could be followed up for more than 20 months (133 excluded). The remaining 560 subjects were included. Among these subjects, 77 were receiving medication for hypertension, 43 for dyslipidaemia and 11 for hyperuricaemia. The distributions of these subjects among the quartiles of percent predicted value of %FVC and percent value of 1 s/FVC (FEV1/FVC ratio) were not significantly different.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kochi University.

75 g oral glucose tolerance test

DM and prediabetes were diagnosed according to the 2003 criteria of the WHO.17 Subjects with prediabetes were classified into two categories: isolated IFG and IGT. Isolated IFG was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level of 6.1–6.9 mmol/l and a 2 h postload plasma glucose level of <7.8 mmol/l; and IGT was defined by a fasting plasma glucose level of <7.0 mmol/l and a 2 h postload plasma glucose level of 7.8–11.1 mmol/l. Blood samples were collected after a 10 h fast, and then 2 h after a 75 g oral glucose load.

Fasting insulin was measured by an enzyme immunoassay (Dainabot, Tokyo, Japan) with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 3.1–4.4%. The homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) formula, (fasting insulin (mU/l)×fasting glucose (mmol/l))/22.5, was used to calculate the insulin resistance score.

Pulmonary function test

Pulmonary function was measured using a spirometer (Chest HI-801; Chest Co., Tokyo, Japan) by an experienced technician according to the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society.23 The Japanese reference values were used.24

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS, V.18.0 (SPSS Japan Inc, Tokyo, Japan). Statistical comparisons of the baseline characteristics of each group were performed using either the χ-square test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons among the groups were performed by using post-hoc Tukey test. In the cross-sectional study, logistic regression models were used to estimate the relevant ORs. In the longitudinal study, the HR of each covariate for the risk of development of prediabetes with 95% CI was calculated using the Cox hazard model. Tests for a linear trend across increasing categories of spirometric indices were conducted by treating the categories as continuous variables in a model. In all analyses, p<0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline analysis

At baseline, our study population (n=1058) consisted of 693 normal subjects, 93 with isolated IFG, 167 with IGT and 105 with DM. To examine the relationship between lung function parameters and impaired glucose metabolism, the subjects were divided into quartiles according to baseline %FVC and the FEV1/FVC ratio. Some parameters, including age, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol, differed significantly among the quartiles (table 1). After adjustment for these parameters, impaired glucose metabolism was significantly associated with %FVC (p<0.001), but not with the FEV1/FVC ratio (p=0.80). Specifically, IGT (p=0.04) and DM (p=0.008), but not isolated IFG (p=0.28), were associated with %FVC (table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects with NGT, isolated IFG, IGT and DM in the cross-sectional study

| NGT | Isolated IFG | IGT | DM | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 693 | 93 | 167 | 105 | |

| Current smokers (%) | 48 | 42 | 45 | 50 | 0.54 |

| Age (years) | 49.5±5.5 | 50.9±5.3* | 51.1±5.3** | 52.2±4.7*** | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 169.9±5.7 | 168.8±5.8 | 169.1±6.0 | 168.4±5.0* | 0.03 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1±2.5 | 23.9±3.1** | 24.6±2.8*** | 24.8±3.2*** | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 126.4±16.3 | 135.1±16.4*** | 135.9±18.2*** | 140.2±16.3*** | <0.001 |

| Pack-year smoking | 30.5±15.6 | 38.0±22.6* | 31.1±17.3 | 38.0±18.5** | 0.002 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 80.1±7.0 | 79.6±7.8 | 80.9±7.4 | 79.4±8.5 | 0.36 |

| %FVC | 97.9±14.2 | 96.5±12.9 | 92.0±13.3*** | 89.2±15.7*** | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5.3±0.4 | 6.3±0.2*** | 5.9±0.5*** | 8.1±1.6*** | <0.001 |

| 120 min glucose (mmol/l) | 5.7±1.0 | 6.5±0.8*** | 8.8±0.8*** | 12.4±4.0*** | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.10±0.33 | 5.34±0.36*** | 5.37±0.41*** | 6.57±1.20*** | <0.001 |

| HOMA-R | 1.08±0.56 | 1.91±2.23** | 1.56±0.88*** | 2.33±1.41*** | <0.001 |

| C reactive protein (mg/l) | 0.11±0.29 | 0.09±0.14 | 0.14±0.28 | 0.18±0.46 | 0.13 |

| T-chol (mg/dl) | 202.1±32.6 | 210.0±28.7* | 209.5±36.3* | 214.8±32.2*** | <0.001 |

Values are numbers, percentages (%) or means ±SD.

*p<0.05.

**p<0.01.

***p<0.001 vs NGT.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CRP, C reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HOMA-R, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IFG, increased fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; T-chol, total cholesterol.

Table 2.

ORs*(95% CI) of prediabetes and DM according to the quartiles of %FVC† or FEV1%‡ in the cross-sectional study

| I | II | III | IV | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFG | |||||

| %FVC | 1.0 | 4.60 (1.29 to 16.39) | 2.03 (0.53 to 7.79) | 2.57 (0.69 to 9.60) | 0.06 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.0 | 1.00 (0.32 to 3.12) | 1.39 (0.49 to 3.93) | 1.81 (0.67 to 4.90) | 0.53 |

| IGT | |||||

| %FVC | 1.0 | 1.35 (0.57 to 3.19) | 2.18 (1.02 to 4.05) | 2.59 (1.17 to 5.69) | 0.04 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.0 | 0.60 (0.35 to 1.15) | 0.62 (0.37 to 1.16) | 0.50 (0.30 to 1.02) | 0.12 |

| IFG or IGT | |||||

| %FVC | 1.0 | 2.18 (1.08 to 4.42) | 2.09 (1.04 to 4.18) | 2.55 (1.28 to 5.09) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.0 | 0.56 (0.31 to 1.07) | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.14) | 0.65 (0.36 to 1.17) | 0.29 |

| DM | |||||

| %FVC | 1.0 | 3.77 (1.29 to 11.03) | 1.28 (0.41 to 3.99) | 2.50 (0.87 to 7.16) | 0.02 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.0 | 2.08 (0.72 to 5.99) | 3.05 (1.12 to 8.31) | 2.13 (0.76 to 6.00) | 0.18 |

| IFG or IGT, or DM | |||||

| %FVC | 1.0 | 3.32 (1.71 to 6.42) | 2.04 (1.06 to 3.94) | 3.33 (1.74 to 6.38) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.0 | 0.74 (0.40 to 1.35) | 0.98 (0.56 to 1.75) | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.49) | 0.70 |

*OR was adjusted for age, BMI, pack-year smoking, systolic BP and T-chol.

†%FVC quartile; I (highest group) (≥104.2%), II (96.0%≤%FVC<104.2%), III (86.4%≤%FVC<96.0%), IV (lowest group) (%FVC<86.4%).

‡FEV1/FVC quartile; I (highest group) (≥85.0), II (81.1%≤FEV1/FVC<85.0%), III (76.5%≤FEV1/FVC<81.1%), IV (lowest group) (FEV1/FVC<76.5%).

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IFG, increased fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; T-chol, total cholesterol.

Frequencies of newly diagnosed prediabetes in subjects with NGT

After the observation period (mean±SD: 28.4±6.1 months), there were 44 subjects with isolated IFG and 58 with IGT among those previously categorised as NGT (n=560), but no subject developed DM. As shown in table 3, there were significant differences in several parameters at baseline, including height, BMI, systolic blood pressure and %FVC, but not in FEV1/FVC ratio.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of subjects who remained NGT, developed isolated IFG and IGT in the longitudinal study.

| NGT | Isolated IFG | IGT | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 458 | 44 | 58 | |

| Current smokers (%) | 48 | 30* | 50 | 0.05 |

| Age (years) | 49.3±5.7 | 50.2±4.4 | 50.5±4.9 | 0.14 |

| Height (cm) | 169.9±5.6 | 170.2±4.9 | 167.1±6.7** | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0±2.5 | 23.8±2.3* | 23.7±3.0* | 0.04 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 125.4±16.7 | 130.5±16.9* | 129.3±14.5 | 0.048 |

| Pack-year smoking | 29.9±15.6 | 31.1±12.1 | 30.1±18.5 | 0.97 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 80.1±7.1 | 79.7±6.3 | 79.9±7.9 | 0.95 |

| %FVC (%) | 97.5±14.2 | 93.0±14.7* | 90.0±16.0*** | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5.3±0.4 | 5.6±0.2*** | 5.5±0.3** | <0.001 |

| 120 min glucose (mmol/l) | 5.6±0.9 | 6.0±1.2 | 6.4±0.9*** | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.07±0.33 | 5.31±0.37*** | 5.19±0.30* | <0.001 |

| HOMA-R | 1.04±0.53 | 1.19±0.61 | 1.31±0.64** | 0.001 |

| C reactive protein (mg/l) | 0.10±0.23 | 0.18±0.42 | 0.16±0.30 | 0.26 |

| T-chol (mg/dl) | 201.4±34.5 | 205.3±27.1 | 212.5±28.6* | 0.05 |

| Duration (month) | 28.6±6.2 | 28.5±5.1 | 27.6±5.6 | 0.13 |

Values are number, percentage (%) or mean±SD.

*p < 0.05.

**p<0.01.

***p<0.001 vs NGT.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CRP, C reactive protein; HOMA-R, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IFG, increased fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; T-chol, total cholesterol.

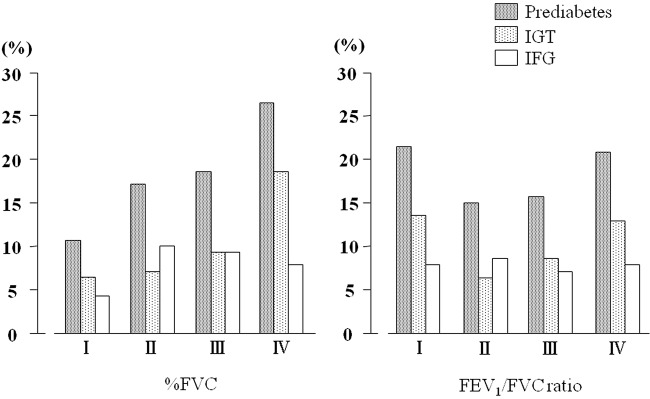

Lung function parameters were divided into quartiles according to baseline %FVC and the FEV1/FVC ratios. Among the quartiles the parameters, including age, BMI and systolic blood pressure, were significantly different (data not shown). Both in the crude model and following adjustment by age, BMI, pack-year smoking and systolic blood pressure, the development of prediabetes occurred significantly more frequently in the lowest quartile of %FVC, but not in that of the FEV1/FVC ratio (table 4). Among prediabetes, IGT, but not isolated IFG, was significantly associated with %FVC, as in the baseline cross-sectional analysis (table 4; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incidences of newly diagnosed prediabetes, isolated IFG and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) according to quartiles of % FVC and the FEV1/FVC ratio. The incidence of prediabetes was significantly associated with %FVC, but not with the FEV1/FVC ratio (p=0.01). Among subjects with prediabetes, lower %FVC was significantly associated with a higher incidence of IGT (p=0.04), but not of IFG (p=0.47).

Table 4.

HRs (95% CI) for development of isolated IFG or IGT according to the quartiles of %FVC*or FEV1%†

| I | II | III | IV | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFG | |||||

| %FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 0.85 (0.38 to 1.92) | 0.81 (0.36 to 1.79 | 1.96 (0.71 to 5.26) | 0.31 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.07 (0.48 to 2.39) | 1.35 (0.60 to 3.03) | 0.54 (0.20 to 1.49) | 0.32 |

| FEV1/FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 0.96 (0.42 to 2.17) | 1.20 (0.51 to 2.86) | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.27) | 0.95 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 0.99 (0.43 to 2.31) | 0.84 (0.35 to 2.00) | 1.04 (0.45 to 2.47) | 0.96 |

| IGT | |||||

| %FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.96 (1.00 to 3.85) | 2.63 (1.27 to 5.56) | 3.03 (1.43 to 6.67) | 0.006 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 2.22 (1.02 to 3.88) | 2.26 (1.07 to 4.78) | 2.74 (1.26 to 5.98) | 0.02 |

| FEV1/FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 2.13 (0.96 to 4.76) | 1.67 (0.81 to 3.45) | 1.03 (0.54 to 1.96) | 0.15 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 2.09 (0.92 to 4.72) | 1.69 (0.81 to 3.52) | 1.11 (0.57 to 2.16) | 0.10 |

| IFG or IGT | |||||

| %FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 2.13 (0.93 to 3.03) | 1.85 (1.03 to 3.57) | 2.63 (1.43 to 4.76) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.48 (0.89 to 2.44) | 1.38 (0.82 to 2.34) | 2.40 (1.30 to 4.44) | 0.04 |

| FEV1/FVC | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.47 (0.84 to 2.56) | 1.47 (0.85 to 2.56) | 1.01 (0.61 to 1.69) | 0.32 |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.47 (0.83 to 2.61) | 1.47 (0.84 to 2.56) | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.84) | 0.21 |

*%FVC quartile; I (highest group) (≥106.0%), II (96.6%≤%FVC<106.0%) III (88.1%≤%FVC<96.6%), IV (lowest group) (%FVC<88.1%).

†FEV1/FVC quartile; I (highest group) (≥85.0%), II (80.9%≤FEV1/FVC<85.0%), III (76.0%≤FEV1/FVC<80.9%), IV (lowest group) (FEV1/FVC<76.0%).

IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IFG, increased fasting glucose.

Model 1 denotes crude model and model 2, adjusted for age, BMI, pack-year smoking and systolic BP.

Discussion

In the baseline cross-sectional study, we found that a low %FVC, but not a low FEV1/FVC ratio, was significantly associated with increased prevalences of prediabetes and DM. As lung function might be impaired by DM, a causal effect of lung function on DM could not be established by these data. Therefore, we also explored prospectively the effect of lung function on the development of newly diagnosed prediabetes in the population with normal glucose metabolism, as evidenced by the results of an OGTT. We found that reduced lung volume (%FVC), but not airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC ratio), was significantly associated with the future development of prediabetes.

This study demonstrated that IGT, but not IFG, was closely associated with lower lung volume in both cross-sectional and longitudinal settings. Our finding was supported by previous studies conducted in an Asian population with relatively low BMI but high smoking prevalence.8 9 In addition, such association between lower lung function and impaired glucose metabolism was also demonstrated in Western populations with higher BMI but lower smoking prevalence, and the association had been shown to be independent of smoking or obesity (refs. 1–6, for review ref. 7).

The mechanisms for the association are not clarified at present. It has been suggested that IGT is caused mainly by insulin resistance in the muscle, and IFG mainly by insulin resistance in the liver.25 Reduced lung volume is associated with reduced maximum oxygen uptake, which may lead to poorer physical fitness and physical activity, and thus result in insulin resistance and DM.26–28 This may explain why IGT is more closely associated with lung volume. Furthermore, poorer lung function in adulthood may be due to low birth weight or early-life malnutrition,29 30 both of which have been reported to be associated with the development of diabetes.31 Malnutrition as a neonate may be an important early cause of cardiac and metabolic disorders in adulthood as a consequence of fetal programming.32 33

This study had several limitations. The study population was limited to men, owing to the fact that sufficient female subjects were not available at the institute. The occupational cohort used in this study may not be representative of Japanese men in general. For example, the prevalence rates of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia in this cohort were 13% and 7%, respectively (data not shown). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in Japan showed prevalence rate of these in general Japanese men aged 40–60 years, in general, were around 30% and 35%, respectively, suggesting that our occupational cohort may be healthier. Subjects taking medications, including simvastatin, which have been shown to lower the risk of impaired glucose metabolism were not excluded, although the distributions of %FVC and the FEV1/FVC ratio in those taking drugs for hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hyperuricaemia were not significantly different from those of subjects not on such medication.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for a prospective relationship between lung volume and the incidence of newly diagnosed prediabetes among subjects with normal glucose metabolism at baseline. Among subjects with prediabetes, the study also suggests that lung volume may be a risk factor for the development of IGT, which is mainly caused by insulin resistance in the muscle, but not IFG, which is caused mainly by insulin resistance in the liver. Although there is published evidence for an association between COPD and DM, our results suggest that prediabetes is not associated with at least the early stage of COPD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone West Corporation Chugoku Health Administration Center.

Footnotes

Contributors: TY contributed to the collection of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the draft. AY contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, editing of the draft and acquisition of funding. YK and SM contributed to the collection of data and analysis, YH, NH and KY contributed to the collection and interpretation of data, and editing the draft. NK contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and editing of the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (No. 23390222 and 24659405), and a grant to the Respiratory Failure Research Group from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee of Kochi University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Engström G, Janzon L. Risk of developing diabetes is inversely related to lung function: a population-based cohort study. Diabet Med 2002;19:167–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Mannino DM; National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study Prospective association between lung function and the incidence of diabetes: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2966–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Associations of measures of lung function with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study. Diabetologia 2004;47:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh HC, Punjabi NM, Wang NY, et al. Cross-sectional and prospective study of lung function in adults with type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Diabetes Care 2008;31:741–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HM, Le H, Lee BT, et al. Forced vital capacity paired with Framingham Risk Score for prediction of all-cause mortality. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1002–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickson DA, Burchfiel CM, Liu J, et al. Diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and metabolic biomarkers in individuals with normal glucose tolerance are inversely associated with lung function: the Jackson Heart Study. Lung 2011;189:311–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein OL, Krishnan JA, Glick S, et al. Systematic review of the association between lung function and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2010;27:977–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heianza Y, Arase Y, Tsuji H, et al. Low lung function and risk of type 2 diabetes in Japanese men: the Toranomon Hospital Health Management Center Study 9 (TOPICS 9). Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:853–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon CH, Rhee EJ, Song JU, et al. Reduced lung function is independently associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Korean men. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2012;11:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinden NJ, Stockley RA. Systemic inflammation and comorbidity in COPD: a result of ‘overspill’ of inflammatory mediators from the lungs? Review of the evidence. Thorax 2010;65:930–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, et al. Prevalence and outcome of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:962–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwamoto H, Yokoyama A, Kitahara Y, et al. Airflow limitation in smokers is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, et al. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax 2010;65:956–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis WA, Knuiman M, Kendall Pet al. Glycemic exposure is associated with reduced pulmonary function in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:752–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrlich SF, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Van Den Eeden SK, et al. Patients diagnosed with diabetes are at increased risk for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and pneumonia but not lung cancer. Diabetes Care 2010;33:55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011;364:829–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabetes Med 2002;19:708–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiao Q, Jousilahti P, Eriksson J, et al. Predictive properties of impaired glucose tolerance for cardiovascular risk are not explained by the development of overt diabetes during follow-up. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2910–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabir MM, Hanson RL, Dabelea D, et al. Plasma glucose and prediction of microvascular disease and mortality: evaluation of 1997 American Diabetes Association and 1999 World Health Organization criteria for diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:1113–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singleton JR, Smith AG, Bromberg MB. Increased prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance in patients with painful sensory neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1448–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Thoracic Society Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:1107–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee report of pulmonary physiology in Japan Respiratory Society Reference values for spirogram and arterial blood gas analysis in Japanese. (In Japanese.) Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 2001;39:1S–17S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdul-Ghani MA, Jenkinson CP, Richardson DK, et al. Insulin secretion and action in subjects with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study. Diabetes 2006;55:1430–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson KF, Lindgärde F. Poor physical fitness, and impaired early insulin response but late hyperinsulinaemia, as predicts of NIDDM in middle-aged Swedish men. Diabetologia 1996;39:573–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burney PG, Hooper R. Forced vital capacity, airway obstruction and survival in a general population sample from the USA. Thorax 2011;66:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Venker C, et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax 2011;65:499–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orfei L, Strachan DP, Rudnicka AR, et al. Early influences on adult lung function in two national British cohorts. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:570–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebert S, Sharkey D, Budge H, et al. The early programming of metabolic health: is epigenetic setting the missing link? Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1953S–8S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Owen CG, et al. Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;300:2886–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osmond C, Barker DJ. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:545S–53S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of adult disease. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:588S–95S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.