Abstract

Objective

To develop a predictive risk stratification model for the identification of preterm infants at risk of 2-year suboptimal neuromotor status.

Design

Population-based observational study.

Setting

Regional preterm infant follow-up programme (Loire Infant Follow-up Team (LIFT) cohort) implemented in 2003.

Participants

4030 preterm infants were enrolled in the LIFT cohort, and examined by neonatologists using a modified version of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool.

Main outcome criteria

2 year neuromotor status based on clinical examinations was conducted by trained paediatricians and parents’ responses to the Ages and Stages Questionnaire were reported.

Results

At 2 years of corrected age, 3321 preterm infants were examined, and suboptimal neuromotor status was found in 355 (10.7%). The study population was divided into training and validation sets. In the training set, 13 neonatal neurological items were associated with a 2-year suboptimal neuromotor status. Having at least one abnormal item was defined as an abnormal neurological status at term. In the validation set, these data predicted a 2-year suboptimal neuromotor status with a sensitivity of 0.55 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.62) and a specificity of 0.65 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.67). Two predictive risk stratification trees were built using the training set, which were based on the neurological assessment at term along with either gestational age or severe cranial lesions or birth weight. Using the validation set, the first tree identified a subgroup with a relatively low risk of suboptimal neuromotor status (3%), representing 32% of infants, and the second tree identified a subgroup with a risk of 5%, representing 42% of infants.

Conclusion

A normal neurological assessment at term allows the identification of a subgroup of preterm infants with a lower risk of non-optimal neuromotor development at 2 years.

Keywords: NEONATOLOGY

Article summary.

Article focus

Preterm infants born before 35 weeks of gestation should receive follow-up care to identify disabilities.

However, it could be a real challenge because the number of surviving infants increases with gestational age, which would potentially lead to excessive costs and lack of resources for universal access to follow-up.

The aim of this study was to develop a risk stratification model, including neurological assessment at term, to identify a population with a lower risk of neuromotor impairment at 2 years of corrected age.

Key message

A normal neurological assessment at term helps to identify a large subgroup of preterm infants with a lower risk of neuromotor impairment at 2 years of corrected age.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main limitation of this cohort study is neuromotor evaluation at 2 years, because most of the evaluations were performed by the 120 trained paediatricians, and not by the highly trained examiners, neuropaediatricians or rehabilitation physicians.

But it is also the strengths: it is a population-based study and this is a strong aspect because it better describes real-life conditions.

Introduction

High preterm infants, born before 32 weeks of gestation, are at a risk of developing neurodevelopmental disabilities, with rates of cerebral palsy as high as 5% to 15%.1–3 However, moderate preterm infants, born before 35 weeks of gestation, are also at risk. Indeed, although more mature infants usually experience better outcomes, 4% of children born at 33 weeks and 1% of children born at 34 weeks present cerebral palsy at 5 years, 10-fold of that expected in a general population.4 Thus, preterm infants born before 35 weeks of gestation should receive follow-up care to identify disabilities and improve outcomes. However, it could be a real challenge because the number of surviving infants increases with gestational age, which would potentially lead to excessive costs and lack of resources for universal access to follow-up.

Neuroimaging data are often used to predict outcome. In fact, abnormal findings on MRI in high preterm infants at term-equivalent age can predict neuromotor impairment at 2 years of age and also be used to stratify infants by risk.5–7 However, MRI use in daily practice is significantly limited by the cost, accessibility and expertise required. Cranial ultrasounds are routinely performed in neonatal intensive care units, and a strong correlation between severe lesions observed on neonatal cranial ultrasound and school-age MRI has been reported.6 Moreover, neonatal cranial ultrasound is highly reliable for the detection of intraventricular haemorrhage and cystic white matter injury, although its ability to accurately diagnose non-cystic lesions is limited.8 Thus, the value of cranial ultrasound in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates remains controversial. This concerns cognitive development rather than cerebral palsy.9 10 Indeed, a relatively low sensitivity to predict cerebral palsy has been reported in a population-based study.11

Amiel-Tison12 13 has developed a clinical instrument for the neurological assessment of preterm infants at term. This instrument considers signs that depend on the integrity of upper structures, such as passive and active tones in the axis and limbs, spontaneous movements, behaviour and alertness, as well as cranial characteristics. Interobserver reliability of the Amiel-Tison assessment tool is very good, and when performed by a highly trained examiner, the results correlate with developmental performance at 2 years of corrected age.14–16

Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a risk stratification model for predicting the neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age, using a modified version of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool at term.

Methods

Study population

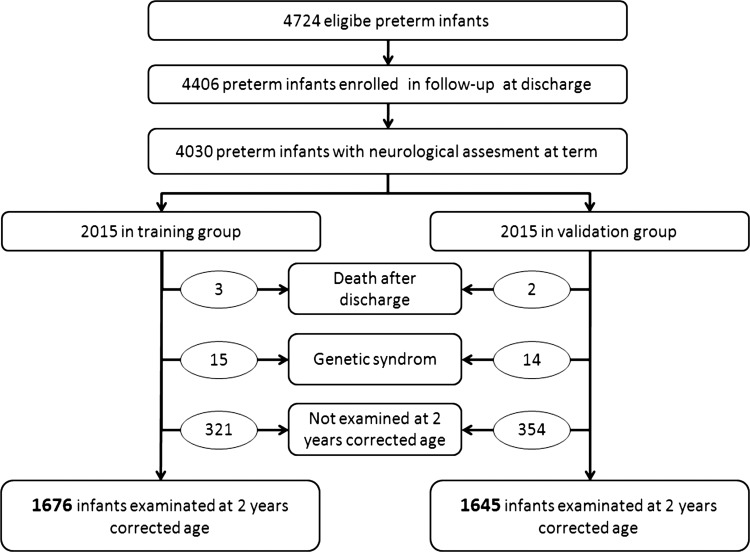

The study population consisted of surviving preterm infants, born before 35 weeks of gestation between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2008 and enrolled in the Loire Infant Follow-up Team (LIFT) cohort (figure 1). Written consent was obtained at enrolment. The cohort was registered at the French Comité National Informatique Et Liberté (no. 851117).

Figure 1.

Cohort profile.

Neonatal neurological status

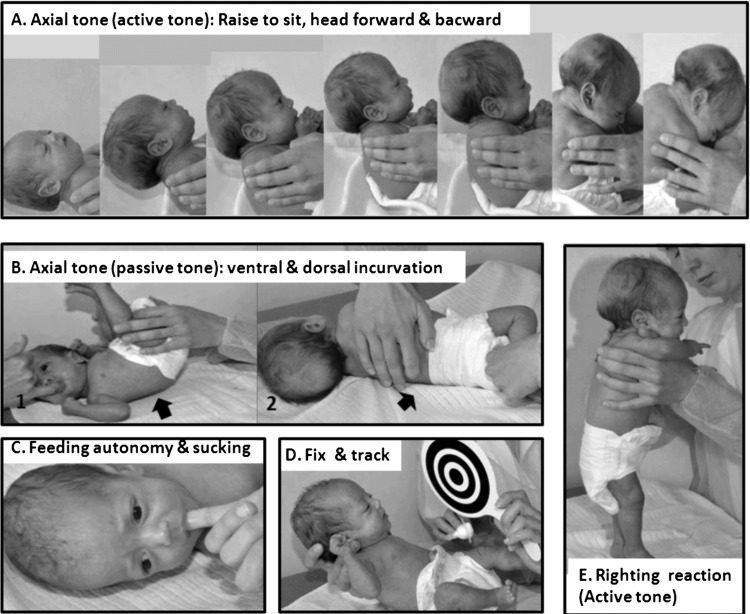

Neurological assessment was performed as described by Amiel-Tison by a neonatologist, who examined all preterm infants upon enrolment in the study and during the week preceding discharge. Amiel-Tison and Gosselin trained neonatologists for administering the neurological assessment tool at 2 years of age. This assessment is divided into six sections and includes 35 items covering neurosensory aspects, cranial morphology, passive and active muscle tones, spontaneous motor activity and primary reflexes. The original scoring system is based on a three-point ordinal scale wheren ‘0’ corresponds to a typical response, ‘1’ to a moderately abnormal response, and ‘2’ to a definitely abnormal response. However, in the present study, we have used a modified version of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool, because we have combined some items into a single item (ie, head circumference, anterior fontanels, squamous sutures and other sutures were combined into cranial morphology). Moreover, seven items were not analysed because they were previously described as poorly informative owing to their rarity (ocular signs, seizures, Moro reflex and fasciculation of the tongue), lack of relevance in preterm infants (high arched palate) or poor interobserver reproducibility (palmar grasp and asymmetric tonic neck).12 Finally, 16 items were analysed: adaptedness during assessment, social interaction, excitability, feeding autonomy and non-nutritive sucking, spontaneous motor activity, response to voice, visual fixing and tracking, lower limbs recoil, popliteal angle, upper limbs recoil, scarf manoeuvre, ventral or dorsal incurvation, comparison of curvatures, pull to sit and reverse manoeuvre, righting reaction and cranial morphology (figure 2). For each item, a dichotomous score was recorded (normal: 0 vs abnormal: 1 or 2), and when an item was not recorded as abnormal, it was considered normal.

Figure 2.

Five of the 13 items from the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool at term were significantly associated with suboptimal neuromotor developmental status at 2 years. (A) Active tone in flexor and extensor muscles of the neck: pull to site manoeuvre from left to right and back-to-lying response from back to left. Both responses are comparable at term; (B) passive tone in the body axis: ventral incurvation (B1) typically exceeds dorsal incurvation (B2); (C) non-nutritive sucking: sucking movements occur by burst. The resulting negative pressure is perceived; (D) visual fixing and tracking: semireclined position on a flat hand; when visual fixation of the target is obtained, tracking is tested on both sides; (E) active tone in the body axis: when placed in the standing position, a strong contraction of the antigravity muscles is observed; the infant is able to support his/her body weight for a few seconds without hyperextension.

Neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age

The children were then evaluated at 2 years of corrected age by trained paediatricians of our regional follow-up network.17 The paediatricians received yearly training concerning a 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment, which was provided by Amiel-Tison and Gosselin in 2003–2006. The children were then classified as showing suboptimal neuromotor function when severe neuromotor impairment (resulting in a diagnosis of cerebral palsy with inability to walk independently) or milder signs (consistent with independent walking by 2 years of corrected age, such as phasic stretch in the triceps surae muscle and imbalance of passive axial tone with a predominance of extensor tone) were detected. Neurodevelopmental assessment also included the parent-completed ages and stages questionnaires (ASQ).9 This tool assesses five domains of child development: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving and personal-social. If an abnormal response was recorded for the two neuromotor domains (gross motor and fine motor), the child was classified as showing suboptimal neuromotor function, in order to limit the risk of underestimating suboptimal neuromotor status.

Statistical analysis

The total population with assessment at term or near term was split into two groups: a training group and a validation group. The items significantly associated with suboptimal neuromotor status in the training group were selected, and sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios were calculated for these items and for their combination.

Next, the number and frequency of children with suboptimal neuromotor status in case of no abnormal item, one or two abnormal items and three or more abnormal items were calculated. To validate our encoding strategy (ie, when an item was not recorded as abnormal, it was considered normal), we compared our results obtained for the association between neurological status at term and outcome at 2 years, with the results obtained with 50 datasets where non-recorded items were imputed using a multiple imputation module included in the SPSS Statistics software.

Finally, two predictive risk stratification trees were built using the training dataset. The purpose was to establish a diagnostic decision tree capable of distinguishing between children with optimal or suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age. In the first tree, gestational age, severe cranial lesions detected by neuroimaging and abnormal neurological status at term, defined as presenting at least one abnormal item, were included in the model and prioritised by χ2 automatic interaction detector analysis. In the second tree, only birth weight and abnormal neurological status were included. Then, the validation dataset was used to validate the items’ prioritisation and the two diagnostic trees. All p values resulted from two-sided tests. The analyses were performed with SPSS V.19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) except for sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratio calculation, performed with the Diagnostic Test Calculator (Department of Medical Education, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

From the 4724 infants deemed eligible, 4406 were enrolled in the LIFT cohort and 4030 received a neurological examination at term. All 16 items were completed for 83% of the children, one of the 16 items was not completed for 11%, two items were not completed for 3% and more than two items were not completed for 3% of the children. From the 4030 infants with neurological examination, five died, 29 presented a genetic syndrome, 3321 were examined at 2 years of corrected age and 675 were not examined (figure 2). The 675 children not examined at 2 years were very similar except in terms of birth year (table 1). The 4030 infants with a recorded neurological examination at term were split into two groups: a training group and a validation group. These two groups were not significantly different (table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison between infants examined and not examined at 2 years of corrected age

| Examined at 2 years | Not examined at 2 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=3321 (%) | n=675 (%) | p Value | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||||

| 22–26 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 0.06 | |

| 27–28 | 9.0 | 8.0 | ||

| 29–30 | 14.8 | 12.4 | ||

| 31–32 | 25.4 | 23.3 | ||

| 33–34 | 46.1 | 52.3 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | ||||

| 450–999 | 12.8 | 11.3 | 0.29 | |

| 1000–1499 | 25.5 | 23.4 | ||

| 1500–1999 | 36.0 | 36.9 | ||

| 2000 and more | 25.7 | 28.4 | ||

| Male | 54.6 | 51.4 | 0.13 | |

| Birth year | ||||

| 2003–2004 | 32.1 | 23.6 | 0.001 | |

| 2005–2006 | 33.3 | 36.2 | ||

| 2007–2008 | 34.6 | 42.5 | ||

| Cranial ultrasound/MRI abnormalities | ||||

| No cranial ultrasound, no MRI | 23.0 | 24.0 | 0.54 | |

| No lesions at cranial ultrasound and/or MRI | 69.6 | 70.7 | ||

| Intraventricular haemorrhage (grade II) | 3.6 | 2.7 | ||

| Intraventricular haemorrhage (grades III and IV) | 0.5 | 0.3 | ||

| White matter damage | 3.1 | 2.2 | ||

| White matter damage and intraventricular haemorrhage | 0.2 | 0.1 |

Table 2.

Comparison between the training and validation groups

| Training Group | Validation group | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=2015) (%) | (n=2015) (%) | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||

| 22–26 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 0.24 |

| 27–28 | 9.1 | 8.6 | |

| 29–30 | 15.6 | 13.3 | |

| 31–32 | 24.2 | 25.9 | |

| 33–34 | 46.7 | 47.4 | |

| Birthweight (g) | |||

| 450–999 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 0.96 |

| 1000–1499 | 25.5 | 25.1 | |

| 1500–1999 | 36.1 | 36.2 | |

| ≥2000 | 26.2 | 25.9 | |

| Male | 53.6 | 54.6 | 0.45 |

| Birth year | |||

| 2003–2004 | 30.0 | 30.5 | 0.62 |

| 2005–2006 | 34.6 | 33.2 | |

| 2007–2008 | 35.6 | 36.3 | |

| Cranial ultrasound/MRI abnormalities | |||

| No cranial ultrasound, no MRI | 23.8 | 22.2 | 0.13 |

| No lesion on cranial ultrasound and/or MRI | 68.4 | 71.1 | |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage (grade II) | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Severe cranial ultrasound/MRI abnormalities | 4.2 | 3.2 | |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage (grades III and IV) | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| White matter damage | 3.5 | 2.6 | |

| White matter damage and intraventricular haemorrhage | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| Outcome at 2 years | |||

| Not examined at 2 years | 15.9 | 17.6 | 0.71 |

| Death after discharge | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Genetic syndrome | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| Optimal neuromotor development | 74.2 | 73.0 | |

| Suboptimal neuromotor development | 8.9 | 8.7 | |

| Cerebral palsy without independent walking | 1.6 | 2.1 | |

| Cerebral palsy with independent walking | 3.8 | 4.2 | |

| Gross and/or fine motor domain impairment (ASQ) | 3.5 | 2.4 |

ASQ, ages and stages questionnaires.

In the training group, 180 of 1676 infants (10.7%) presented a suboptimal neurological status at 2 years of corrected age owing to cerebral palsy without independent walking (1.9%), cerebral palsy with independent walking (4.5%) or impairment in gross and/or fine motor function as revealed by the ASQ (4.3%). Thirteen of the 16 items of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool at term were significantly associated with suboptimal neurological status at 2 years. The specificity of all items was higher than 0.88, and the sensitivity was always lower than 0.20 (table 3). The abnormal neurological assessment at term, defined as children with one or more abnormal items, was significantly associated with suboptimal neurological outcome at 2 years, with a specificity of 0.70 (0.67 to 0.71), a sensitivity of 0.48 (0.41 to 0.56), a positive likelihood ratio of 1.59 (1.34 to 1.89) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.74 (0.64 to 0.86). Two predictive risk stratification trees were built. The first tree, including the abnormal neurological assessment at term, gestational age and the severe cranial lesions on imaging identified a subgroup of 508 (30%) preterm infants having a relatively low risk of suboptimal neurological outcome (5%) at 2 years of corrected age. The third node was ‘abnormal neurological assessment at term’, the second node was ‘severe cranial lesions’ and the first node was ‘gestational age less than 27 weeks’. The second tree, including neurological assessment at term and birth weight, identified a subgroup of 698 (42%) preterm infants with a relatively low risk of suboptimal outcome (6%). The first node was neurological assessment at term.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity and positive likelihood ratio for predicting suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years

| Items | Validation group (n=1645) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurosensory function and spontaneous activity during assessment | ||||

| Spontaneous motor activity | 19 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.09) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | 6.11 (2.50 to 14.98) |

| Response to voice | 43 | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.12) | 0.98 (0.98 to 0.98) | 3.64 (1.94 to 6.85) |

| Visual fixing and tracking | 179 | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.24) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.91) | 1.76 (1.24 to 2.50) |

| Social interaction | 48 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.13) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | 3.46 (1.90 to 6.31) |

| Excitability | 28 | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.09) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | 3.98 (1.83 to 8.66) |

| Passive tone | ||||

| Upper limbs recoil | 78 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.13) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) | 1.84 (1.05 to 3.21) |

| Lower limbs recoil | 55 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.10) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 1.87 (0.96 to 3.64) |

| Comparison of curvatures | 42 | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.14) | 0.98 (0.98 to 0.99) | 5.17 (2.83 to 9.45) |

| Active tone | ||||

| Pull to sit manoeuvre | 187 | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.24) | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.91) | 1.67 (1.17 to 2.37) |

| Righting reaction | 51 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.10) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) | 2.05 (1.05 to 4.02) |

| Others | ||||

| Adaptedness during assessment | 132 | 0.19 (0.05 to 0.14) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) | 7.32 (1.05 to 4.02) |

| Non-nutritive sucking/feeding autonomy | 54 | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.14) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 3.23 (1.81 to 5.73) |

| Head circumference | 167 | 0.19 (0.14 to 0.26) | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.92) | 2.15 (1.52 to 3.02) |

| Items combination | ||||

| One item or more | 615 | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.62) | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.67) | 1.55 (1.33 to 1.81) |

| Three items or more | 108 | 0.19 (0.14 to 0.25) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 3.70 (2.53 to 5.40) |

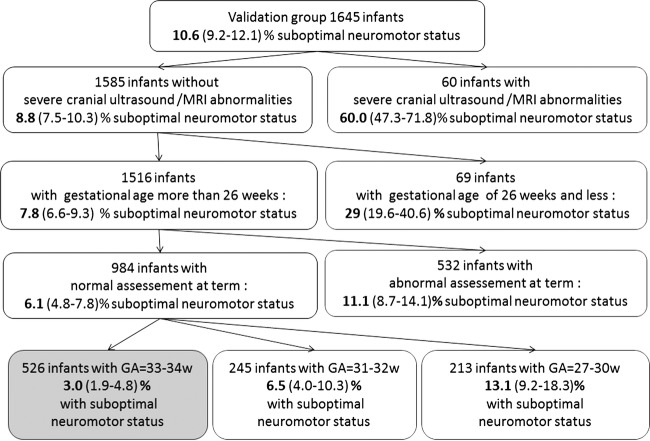

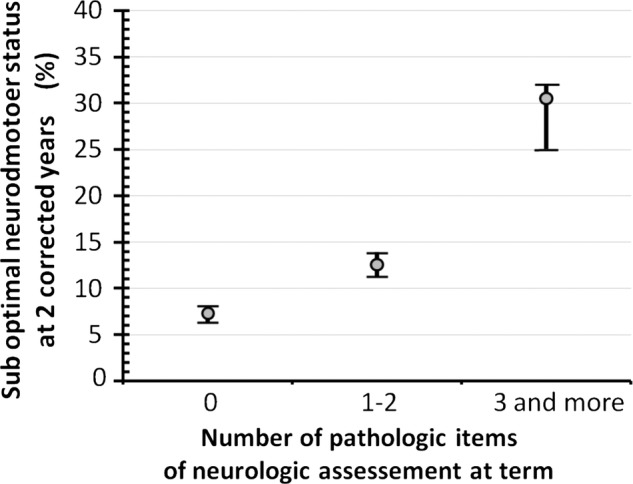

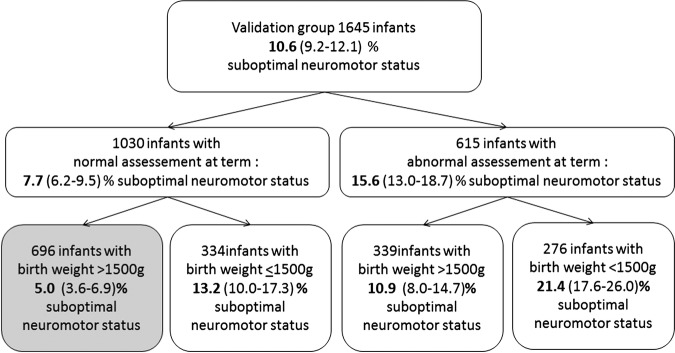

In the validation group, 175 of 1645 infants (10.6%) had a suboptimal neurological status at 2 years of corrected age owing to cerebral palsy without independent walking (2.5%), cerebral palsy with independent walking (5.1%) or impairment in gross and/or fine motor function as revealed by the ASQ (3%). Twelve of the 13 items of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment tool at term selected in the training group were significantly associated with neurological outcome. Specificity, sensitivity and positive likelihood of each item are reported in table 1. Specificity and sensitivity of the abnormal neurological assessment at term were 0.64 (0.62 to 0.66) and 0.56 (0.48 to 0.63), respectively, for predicting suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years, and 0.65 (0.62 to 0.67) and 0.55 (0.48 to 0.61), respectively, for predicting cerebral palsy. The predictive capacity for suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years increased with the number of items included in the neurological assessment at term (figure 3). Also, the predictive capacity for suboptimal outcome increased when calculated with a multiple imputation method in 50 datasets. In addition, we validated the two predictive risk stratification trees built using the training group. The first tree included neurological assessment, gestational age and severe cranial lesions, and identified a subgroup of 526 (32%) preterm infants exhibiting a relatively low rate of suboptimal outcome (3%). The second tree only included neurological assessment and birth weight, and identified a subgroup of 696 (42%) preterm infants exhibiting a relatively low rate of suboptimal outcome (5%) (figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Rates of suboptimal neuromotor developmental status at 2 years of corrected age according to the number of abnormal items observed during neurological assessment at term. Circles indicate rates observed in the validation group. Intervals indicate the range of virtual rates calculated in 50 datasets by imputation in case of missing items.

Figure 4.

Classification and regression trees predicting suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age. Trees were built by χ2 automatic interaction detector analysis in the training set. The classifications obtained in the validation group are shown. Each node shows the selected splitting variable, number and proportion (95% CI) of infants with suboptimal outcome at 2 years. The terminal nodes marked in grey represent the subgroup of infants considered at ‘low risk’. Neuromotor assessment at term, gestational age and the presence of cerebral lesions on imaging were included in this first model.

Figure 5.

Classification and regression trees predicting suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age. Trees were built by χ2 automatic interaction detector analysis in the training set. The classifications obtained in the validation group are shown. Each node shows the selected splitting variable, number and proportion (95% CI) of infants with suboptimal outcome at 2 years. The terminal nodes marked in grey represent the subgroup of infants considered at ‘low risk’. Neuromotor assessment at term and birth weight were included in this second model.

Discussion

A normal neurological status at term predicts a lower risk of suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age. Thus, the neurological examination at term, including the five following elements (feeding autonomy and non-nutritive sucking, visual fixing and tracking, comparison of ventral and dorsal curvatures, pull to sit and reverse manoeuvre and righting reaction), should be assessed at term by a neonatologist or by a general practitioner during the follow-up of preterm infants.

Different neonatal neurological assessment tools have been proposed and tested to predict cerebral palsy at 2 years. In a recent review, eight neurological assessment tools were evaluated, although the Amiel-Tison instrument was not included.18 Among them, Prechtl's method for the assessment of general movements had the best sensitivity and specificity for predicting cerebral palsy. However, a comprehensive review of all the studies using Prechtl's method revealed that specificity and sensitivity varied depending on the studies, but mostly on the judgement criterion and population studied.19 Moreover, a study comparing the methods of Amiel-Tison and Prechtl showed that the correlation between neurological and developmental outcome was better with the Amiel-Tison method.20 Thus, the Amiel-Tison tool for neurological assessment at term seems to be a robust instrument and should be recommended, even in the simplified form that we have presented in this study. Nevertheless, several limitations apply to studies evaluating neurological assessment: (1) they always include fewer than 200 infants, and most of the time fewer than 60; (2) the examination is usually performed by experts, and often by direct collaborators of the author of the study and (3) the examiners are very rarely blinded to the neonatal assessment results, which may influence how they score a child on the outcome measures. In the present study, the number of infants included is consequent; more than 120 different paediatricians performed the evaluations, and most of them were blinded to the initial neonatal assessment. In real-life conditions, we obtained a good specificity with our model, and with an acceptable sensitivity when adding risk factors, such as a low gestational age or severe cerebral lesions observed by imaging.

Severe cerebral lesions detected on imaging constituted the main criterion for neuromotor status prediction, especially cerebral palsy.10 In a large cohort, a good correlation was found between severe lesions on neonatal cranial ultrasound and MRI at term. Mild MRI abnormalities, rather than mild ultrasound abnormalities, were associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes.6 The sensitivity and specificity of neonatal cranial ultrasound for predicting cerebral palsy at 20 months were 29% and 86% vs 71% and 91%, respectively, for MRI in the study by Mirmiran.21 In Inder's9 study, the sensitivity of moderate-to-severe MRI abnormalities for predicting cerebral palsy was 65, with a specificity of 79%. Thus, MRI shows a little better sensitivity than neuromotor assessment in the short term, but with a much better specificity. MRI in very low birth weight preterm neonates seems superior to cranial ultrasound to predict cerebral palsy, but MRI is not always available (MRI was not systematically performed in this cohort). In sum, cerebral imaging remains the main criterion, despite a lower sensitivity and specificity being reported in population-based studies compared to institutional studies.11 In our population-based study, 80% of the preterm infants with suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years did not show severe neonatal cerebral lesions by brain imaging. However, 60% of infants with severe cerebral lesions had a suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years. Thus, our study confirms that cerebral lesions are the most important predictors of cerebral palsy in preterm infants.22

Gestational age is another classical criterion used to select children for follow-up enrolment. A very low gestational age (ie, less than 27 weeks of gestation) is a very specific predictor of suboptimal outcome, but it concerns only 12% of the infants with suboptimal neuromotor status. If we increase the gestational age cut off (ie, to 30, 32 or 34 weeks of gestation), the predictive sensitivity increases, but the specificity decreases. The fact that preterm infants born at 33–34 weeks of gestation without severe cerebral lesions on imaging do not receive follow-up care means that up to 22% of infants with a suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years do not receive appropriate follow-up care. Thus, gestational age should not be the only criterion used. In countries where gestational age is not reliable, and access to cranial ultrasound and MRI is limited, the combination of neurological assessment at term and birth weight seems to be an acceptable compromise to detect children at higher risk for suboptimal neuromotor status at 2 years of corrected age.

The main limitation of this cohort study was neuromotor evaluation at 2 years, because most of the evaluations were performed by the 120 trained paediatricians, and not by the highly trained examiners, neuropaediatricians or rehabilitation physicians. Indeed, although cerebral palsy with or without independent walking is relatively easy to diagnose, it is more difficult to diagnose infants with mild neuromotor disability. For this reason, we took into account two domains of the ASQ regarding neuromotor status (gross and fine motor functions). Despite this fact, the population with suboptimal neuromotor status might have been underestimated. Nevertheless, this study was population based, and not institution based, which is a strength because it better describes real-life conditions. Moreover, sensitivity and specificity were similar when they were calculated for predicting cerebral palsy only. Another limitation was the relationship between assessment at term and at 2 years. Most of the paediatricians who performed the examination at 2 years were blinded to the neonatal neurological assessment results, although they were not blinded to the neonatal history. This could modify the specificity and sensitivity of gestational age or cerebral lesion imaging. However, the fact that most paediatricians were blinded to the neonatal neurological assessment is another strength of this study.

Normal neurological assessment of preterm infants at term, together with gestational age, more than 33 weeks of gestation and no severe cerebral lesions data, is associated with significantly lower risk of suboptimal neuromotor development at 2 years of corrected age. Moreover, a model based on neurological assessment at term and birth weight could identify a subgroup of preterm infants with a lower risk of suboptimal neuromotor development at 2 years. This predictive model could be useful in countries where the gestational age of preterm infants is not known with precision and brain imaging is not available.

In conclusion, a fairly straightforward neurological examination provides clinically useful information, especially when combined with other important determinants of outcome—gestational age, significant imaging abnormalities and birth weight. This neurological examination should be performed in all preterm neonates, prior to discharge or just after, to better inform parents and to better understand the risk of a poor outcome and therefore have a better idea of which baby requires more intensive follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions Professor Julie Gosselin and Dr Claudine Amiel-Tison, who taught and trained the paediatricians of our regional follow-up network for the assessment of neurodevelopment.

Footnotes

Contributors: BG drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SN'G The Tich conceptualised and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. BB coordinated and supervised data collection in all sites, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GG coordinated and supervised data collection in one site, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. VR coordinated and supervised data collection in all sites, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. IB coordinated and supervised data collection in all sites, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. YM coordinated and supervised data collection in one site, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. P-YA carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. J-CR conceptualised and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. CF conceptualised and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The Loire Infant Follow-up Team cohort is supported by grants from the Regional Health Agency of Pays de la Loire.

Competing interests: No funding body had any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Comité National Informatique Et Liberté no. 85117.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1.Larroque B, Ancel PY, Marret S, et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2008;371:813–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, et al. EPICure Study Group. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2005;352:9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, et al. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;302:2235–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marret S, Ancel PY, Marpeau L, et al. Neonatal and 5-year outcomes after birth at 30–34 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Msall ME, Limperopoulos C, Park JJ. Neuroimaging and cerebral palsy in children. Minerva Pediatr 2009;61:415–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rademaker KJ, Uiterwaal CS, Beek FJ, et al. Neonatal cranial ultrasound versus MRI and neurodevelopmental outcome at school age in children born preterm. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90:F489–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodward LJ, Anderson PJ, Austin NC, et al. Neonatal MRI to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2006;355:685–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inder TE, Anderson NJ, Spencer C, et al. White matter injury in the premature infant: a comparison between serial cranial sonographic and MR findings at term. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:805–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De vries LS, Van Haastert IC, Benders MJ, et al. Myth: cerebral palsy cannot be predicted by neonatal brain imaging. Semin Fetal Neonatal Me 2011;16:279–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vries LS, Van Haastert IL, Rademaker KJ, et al. Ultrasound abnormalities preceding cerebral palsy in high-risk preterm infants. J Pediatr 2004;144:815–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ancel PY, Livinec F, Larroque B, et al. Cerebral palsy among very preterm children in relation to gestational age and neonatal ultrasound abnormalities: the EPIPAGE cohort study. Pediatrics 2006;117:828–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amiel-Tison C. Clinical assessment of the infant nervous system. In: Levene MI, Lilford RJ, eds. Fetal and neonatal neurology and neurosurgery. 2nd edn London: Churchill Livingstone, 1995: 83–104 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amiel-Tison C. Update of the Amiel-Tison neurologic assessment for the term neonate or at 40 weeks corrected age. Pediatr Neurol 2002;27:196–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschênes G, Gosselin J, Couture M, et al. Interobserver reliability of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment at term. Pediatr Neurol 2004;30:190–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simard MN, Lambert J, Lachance C, et al. Interexaminer reliability of Amiel-Tison neurological assessments. Pediatr Neurol 2009;41:347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simard MN, Lambert J, Lachance C, et al. Prediction of developmental performance in preterm infants at two years of corrected age: contribution of the neurological assessment at term age. Early Hum Dev 2011;87:799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosselin J, Amiel-Tison C. Évaluation neurologique de la naissance à 6 ans. 2nd edn Montréal, Québec: Presses du CHU Ste-Justine/Paris Masson, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble Y, Boyd R. Neonatal assessments for the preterm infant up to 4 months corrected age: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54:129–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darsaklis V, Snider LM, Majnemer A, et al. Predictive validity of Prechtl's method on the qualitative assessment of general movements: a systematic review of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53:896–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paro-Panjan D, Sustersic B, Neubauer D. Comparison of two methods of neurologic assessment in infants. Pediatr Neurol 2005;33:317–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirmiran M, Barnes PD, Keller K, et al. Neonatal brain magnetic resonance imaging before discharge is better than serial cranial ultrasound in predicting cerebral palsy in very low birth weight preterm infants. Pediatrics 2004;114:992–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaino G, Khoshnood B, Kaminski M, et al. Predictors of cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE prospective population-based cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010;52:e119–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.