Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to describe the proportion and characteristics of cancer patients who perceived that better care would have greatly improved their well-being in (1) specific and (2) multiple domains of patient-centred care.

Design

Cross-sectional touchscreen computer survey.

Setting

Four Australian radiation therapy departments located within major urban public hospitals.

Participants

Radiation therapy outpatients were invited to participate in a touchscreen computer survey. Eligible patients were at least 18 years old, diagnosed with cancer and had sufficient English to complete the survey.

Primary outcome measure

Participants were asked whether their well-being could have been greatly improved if better care had been provided across eight domains of patient-centred care. Characteristics of those respondents who identified (1) specific and (2) multiple domains where it was perceived that better care would have greatly improved their well-being were examined.

Results

Of 508 eligible radiation therapy patients, 344 (68%) completed the survey. Patients most frequently perceived that better care in the following domains could have improved their well-being: information and communication about their cancer (22%; 95% CI 18% to 27%); emotional and spiritual support (22%; 95% CI 18% to 27%); management of physical symptoms (21%; 95% CI 17% to 26%) and involvement of friends and family (21%; 95% CI 17% to 26%). Just under one-third of respondents (31%; 95% CI 26% to 36%) indicated that their well-being could have been improved by better care across two or more domains of care. Patients in younger age groups and migrants to Australia had higher odds of endorsing multiple domains where better care would have improved their well-being.

Conclusions

Further investigation of patients’ perceptions of how their perceived quality of care might be improved is warranted, particularly among patients in younger age groups and migrants to Australia.

Keywords: Patient-Centered Care; Cross-Sectional Studies; Neoplasms; Health Care Quality, Access, and Evaluation

Article summary.

Article focus

The Institute of Medicine has indicated the urgency of evaluating and improving the quality of healthcare, including patient-centred care.

We aimed to describe the proportion and characteristics of radiation oncology outpatients who perceived that better care would have greatly improved their well-being in (1) specific and (2) multiple domains of patient-centred care.

Key messages

Just under one-third of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy treatment indicated that their well-being could have been greatly improved by better care across multiple domains of patient-centred care.

Younger patients and migrants to Australia were more likely to identify that better care in multiple domains would be of benefit to their well-being, suggesting that targeted interventions to improve patient-centred care and well-being outcomes for these groups are required.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study involved radiation oncology outpatients with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses, providing treatment centres with guidance about which patient groups may perceive the need for better care in specific and multiple domains of patient-centredness.

The quality of care measure used appeared to have good face validity and internal reliability; however, further examination of its psychometric properties is needed.

Introduction

Why assess patient views of quality of care?

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the USA, an independent organisation for gathering evidence to assist health decision-making, has indicated the urgency of assessing and improving the quality of healthcare.1 Quality healthcare is care that is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable and patient-centred.2 A patient-centred approach to care is defined as being respectful of, and responsive to, patients’ physical, social and emotional preferences and needs.3 Provision of patient-centred care may contribute to improvements in patients’ physical, mental and social well-being.4 5 A patient-centred approach to care is now endorsed as a key component of quality healthcare by many organisations (including the WHO6) and governments (eg, in Australia, the USA, the UK, Canada, Germany, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland7). Although quality of care is often examined through audit and benchmarking of clinical outcomes data,8 examining patients’ judgements of how their experiences of care correspond with their preferences and needs is required in order to assess the quality of patient-centred care.9

What has previous patient-centred care research contributed to knowledge about prioritising quality improvement efforts?

Quality of patient-centred care has been assessed using a variety of patient-reported outcome measures including surveys of patient satisfaction and experiences which are closely linked to the IOM patient-centred care conceptual framework.10 11 Patient satisfaction surveys have been criticised because responses may be heavily dependent upon patients’ expectations of care, leading to the development of patient experience surveys.10 The Picker Institute survey assesses outpatients’ experiences of care across the domains of patients’ preferences; emotional support; physical comfort; information and education; coordination of care; access to care and involvement of family/friends.10 12 13 Recently, indicators of the quality of patient-centred care have been developed from international patient-centred oncology clinical practice guidelines.11 14 These indicators have been grouped across the domains of information; coordination/organisation of care; physical support; emotional and psychological support; communication and respect; involvement; access and follow-up/after-care. To date, these approaches have not attempted to capture patient perceptions of the degree to which their well-being would benefit from improved care across these different domains.15 Drawing upon the formal supportive care needs assessment approach which aims to identify the level of patient need for help,16 identification of patients’ views of the relative benefit that would be conferred by improvements in different patient-centred domains care may assist with identifying and prioritising quality improvement efforts.11

Some subgroups of patients may perceive that they receive poorer care than others. For instance, older patients may be more likely than younger patients to express satisfaction with care, possibly relating to differences in the expectations for care provision.17 Additionally, cancer patients who have clinically significant levels of anxiety have been found to give lower ratings of satisfaction with care.18 Well-being in patients diagnosed with chronic illness may be linked to aspects of social support such as having a partner,19 and also potentially to ethnicity.20 Given that there is some evidence of increased psychological distress and supportive care needs prior to and during cancer treatment,21 22 it may also be that treatment stage may impact on perceptions of care.

Patient-centred care for radiation therapy patients

It is recommended that approximately 50% of cancer patients undergo radiation therapy (RT) treatment.23 Given that this treatment is often characterised by frequent contact with the healthcare system over the course of treatment, the RT setting provides an opportunity for addressing patient perceived needs across the multiple domains of patient-centred care.23 Although research into specific domains and specific cancer types has been conducted in radiotherapy settings,21 24 25 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to ask cancer patients undergoing RT about their perceptions of how better care across multiple patient-centred domains could improve their well-being.26 Further, no previous studies have identified characteristics of RT patients who are likely to perceive better patient-centred care.27

This study aimed to examine the proportion and characteristics of RT patients who indicate that their well-being could have been greatly improved by better cancer care across each of eight domains of patient-centred care. We also aimed to assess characteristics associated with patient perception that better care across multiple domains of patient-centred care would have improved their well-being.

Methods

Ethics approvals

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle and NSW Population & Health Services Research Ethics Committees.

Design

A cross-sectional survey was completed using touchscreen computers.

Participants

Radiation oncology outpatients were recruited from four RT departments in a major urban centre in Australia between March and December 2010. Each RT department was attached to a major public teaching hospital, and had at least three Linear Accelerators available for treatment. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with cancer and had sufficient command of English to complete the touchscreen computer survey. Patients who were receiving both radical and palliative treatment were eligible. Those who were attending the clinic for the first time or who were considered by the clinic staff to be too unwell or unable to give informed consent were excluded.

Procedure

Patients waiting for RT treatment were invited to participate in the study by a research assistant. Consenting patients were given a unique identification code to login to the touchscreen computer questionnaire. If patients were called into their treatment before finishing their survey, they had the option of resuming after their treatment. Touchscreen computer surveys have been reported as being faster and easier to use for outpatients than pencil and paper surveys,28 and have been found to be acceptable to oncology patients.29

Measures

Digivey survey software (CREOSO—Digivey Survey Center, Phoenix, Arizona) was used to programme the patient survey, which was administered using Dell Latitude XT2 touchscreen laptop computers.

Quality of care: patient-centred care

Questions and domain descriptions were developed to correspond with domains of patient-centred care described in the literature,10 11 ensuring face validity of the items and clinical relevance to patients currently undergoing treatment. Survey items were extensively pilot tested and modified based on feedback from 67 patients. Eight items, each assessing a different domain of care, were presented on separate screens with the stem, ‘During my cancer care, my well-being would have been greatly improved by.’ Table 1 lists the eight items and a short description of each domain that was presented at the bottom of the touchscreen. Patients were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a four-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly agree). Internal consistency of the items was assessed using Cronbach's α.

Table 1.

Survey items and descriptions (each assessing a different domain of care)

| Item | On screen description |

|---|---|

| Better management of my physical symptoms | May relate to your pain, sleeplessness, other side-effects and symptoms |

| Better information and communication about my cancer and care | May include: clear and consistent information about your diagnosis, test results, treatment, taking medications, food you should be eating, exercise you can do safely, etc |

| Better emotional and/or spiritual support | May include services or support to help you cope with: the impact of cancer on your life, doubts/worries, feelings of anxiety or sadness, changes to your body images, etc |

| Better services, information and support for my friends/family | May include helping them to cope with the impact of your cancer, or providing opportunities for them to be involved in your care |

| Better staff approachability and respect for me | Describes staff who are easy to contact and up-to-date with your medical history, and who give you opportunities to ask questions and be involved in treatment decisions |

| Getting better access to the care I need when required | Describes not having to wait too long to get appointments, and having treatment and medical advice available when needed |

| Better services/support to cope with changes to my relationships | May include: knowing what changes to expect, and having some strategies to reduce the impact of cancer on your work, usual social activities, friendships or sexual relationships |

| Better services/advice to assist me with practical concerns | May include being able to access financial support, transport to treatment, home help services or other support needed to manage practical issues |

Demographic characteristics

Patient self-report was used to collect age, gender, whether participants were born in Australia, living with a partner and the postcode of participants' usual place of residence.

Disease characteristics

A multiple choice question, ‘What is your most recent primary cancer diagnosis?’ was used to determine respondents’ most recent primary cancer diagnosis. Common cancer types were listed on screen, along with the categories ‘other—please specify’ and ‘don't know’. Approximate time since diagnosis was calculated from the patient's self-reported year and month of diagnosis and their recruitment date. Patients were asked to indicate the number of RT treatment and outpatient appointments they had attended; whether they had experienced a second diagnosis and/or recurrence; and whether they perceived that the aim of their treatment was to cure the cancer, prevent the cancer from coming back or control symptoms of cancer (cure is not possible).

Psychological characteristics

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a 14-item self-report measure of anxiety and depression.30 Both the anxiety and depression subscales provide scores of between 0 and 21 where 0–7=Normal; 8–10=Mild; 11–14=Moderate; 15–21=Severe. The scale has been utilised in research and in clinical practice,31 with demonstrated reliability and validity.32 HADS scores have been found to be comparable when administered by touchscreen computer and pen-and-paper in a population of patients with cancer.33

Statistical methods

RT patients were defined as having endorsed each domain if they indicated that they ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that better care would have greatly improved their well-being. The proportion of patients endorsing each domain was reported with 95% CIs. Respondents were then dichotomised on the basis of: (1) 0–1 domains endorsed or (2) multiple (2 or more) domains endorsed. Univariate logistic analysis was used to investigate the relationship between demographic characteristics, disease factors and psychological distress and patient endorsement of (1) each of the eight domains of care and (2) multiple (2 or more) domains of care requiring improvement. The explanatory variables examined included age (18–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70 plus), sex (male, female), cancer diagnosis (Breast, Prostate, Other/Don't Know), second diagnosis and/or recurrence (no, yes), Australian-born (no, yes), living with a partner (no, yes), anxiety (no, yes), depression (no, yes), usual place of residence (urban/rural, based on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) score), socioeconomic status (SES) (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas average scores34) and the number of radiotherapy treatment appointments attended (continuous measure). Variables with a p value of 0.2 or less on the univariate likelihood ratio test were included in the multiple logistic regression model. The backwards stepwise method was then used to remove all variables with a p value of 0.1 or more on the likelihood ratio test, with the recruitment site included in all multiple regression models. The fit of the final model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test. For individual domains, ORs with 95% CIs are reported for multiple regression models. For the assessment of characteristics associated with endorsing multiple domains, ORs with 95% CIs are reported for univariate and multiple regression models. Analysis was conducted using STATA V.11.2, and a significance level of 0.05 was used.

Sample size and statistical power

We aimed to recruit a total of 450 patients which, based on 50% of patients perceiving the need for better care in each domain, would allow us to obtain prevalence estimates with 95% CIs within ±5% of the point estimate. This sample size would also be sufficient to detect differences of approximately 15% in characteristics between those who perceive the need for better care in each individual domain and also multiple domains of care with 80% power and 5% significance level.

Results

Of the 639 patients screened for eligibility, 110 were ineligible due to: inadequate English (n=51); not currently receiving RT (n=32); had already been approached about the study (n=6); not being diagnosed with cancer (n=3); clinic staff concern about patient burden or ability to give informed consent (n=3); being aged under 18 (n=2) or no specified reason (n=13). Of the 529 eligible patients, 85% (n=451) consented and 69% (n=365) completed the survey. Incomplete surveys were primarily because patients were called into their treatment appointment before survey completion, and no data were available from these surveys. An additional 21 patients were excluded because they reported that they were attending their first RT treatment. Once these participants were ruled ineligible, the overall response rate was 68% of 508 eligible RT patients. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 344 respondents. 51% were men, the median age was 63.3 (Quartile (Q) 1: 52.2, Q3: 70.5) and the median number of weeks since diagnosis was 27.6 (Q1: 16.0, Q3: 57.3). The majority of respondents (97%) were currently receiving RT treatment, with the remainder reporting that they were attending the treatment centre for a check-up. The distribution of primary cancer type within the sample can be seen in table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and disease characteristics of respondents (n=344)

| Characteristic | Mean (min, max) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.4 (18.9–91.4) |

| n (%) | |

| Males | 176 (51%) |

| Region of birth | |

| Australia | 231 (67%) |

| UK/Ireland | 30 (8.7%) |

| Europe | 29 (8.4%) |

| Asia | 25 (7.2%) |

| Other | 29 (8.4%) |

| Perceived palliative treatment aim | 46 (14%) |

| Primary cancer type | |

| Breast | 93 (27%) |

| Prostate | 73 (21%) |

| Head and neck | 33 (9.6%) |

| Colorectal | 20 (5.8%) |

| Brain | 15 (4.4%) |

| Lung | 15 (4.4%) |

| Other | 89 (26%) |

| Don't know | 6 (1.7%) |

| Second diagnosis/recurrence | 96 (28%) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | |

| Completed appointments with cancer doctor | 3 (2, 5) |

| Completed radiation therapy appointments | 9 (4, 17) |

| Weeks since diagnosis | 27.6 (16, 37.3) |

Note: Observations within each variable may not add to the total due to missing values.

Internal consistency of items

When considering the items with responses on a four-point Likert scale, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) was 0.92. When the responses were dichotomised (agree vs disagree), Cronbach's α was 0.89.

Proportion of patients endorsing individual domains of patient-centred care

Table 3 shows the number and proportion of radiation oncology patients who agreed that their well-being could have been improved by better care across eight different domains of patient-centred care. It can be seen that each domain was endorsed by between 12% and 22% of patients.

Table 3.

Proportion who reported that their well-being would have been improved by better care across eight domains (n=344)

| Agree | |

|---|---|

| n (%, 95% CI) | |

| Information and communication about my cancer and care | 76 (22, 18–27) |

| Emotional and/or spiritual support | 75 (22, 18–27) |

| Management of my physical symptoms | 72 (21, 17–26) |

| Services; information and support for my friends/family | 72 (21, 17–26) |

| Services/advice to assist me with practical concerns | 69 (20, 16–25) |

| Access to the care I need when required | 62 (18, 14–23) |

| Services/support to cope with changes to my relationships | 56 (16, 13–21) |

| Staff approachability and respect for me | 42 (12, 8.9–16) |

Characteristics associated with endorsement of domains

Multiple logistic regression analysis identified that Australian-born participants had lower odds of endorsing perceiving ‘better management of physical symptoms’ would have greatly improved their well-being (OR=0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7; p=0.0008). No other characteristics were significantly associated with endorsing better management of physical symptoms.

Better information and communication about my cancer and care: Australian-born patients had lower odds of perceiving that ‘better information and communication about my cancer and care’ would have greatly improved their well-being (OR=0.5; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.9; p=0.0153), as did patients living with a partner (OR=0.5; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8; p=0.0083). It was also found that patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.7) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.8) had lower odds of endorsing this domain than younger participants (p=0.0042). Patients with a likely presence of depression had three times the odds of endorsing this domain (OR=3.1; 95% CI 1.1 to 9.0; p=0.0396).

Better emotional and/or spiritual support: patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.6) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.8) had lower odds of endorsing this domain than younger participants (p=0.0011). Australian-born patients had lower odds of endorsing this domain (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.5; p<0.0001), while patients with clinically significant levels of depression had higher odds of endorsing (OR=3.5; 95% CI 1.2 to 10.1; p=0.0250).

Better services, information and support for my friends/family: lower odds of endorsing this domain were found in older patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.4) compared with younger participants (p<0.0001), and also in Australian-born patients (OR=0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.6; p=0.0004).

Better staff approachability and respect for me: Australian-born patients had significantly lower odds of endorsing this domain (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5; p=0.0001). Marginally non-significantly lower odds of endorsing this domain were found in older patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) compared with younger participants (p=0.0683).

Getting better access to the care I need when required: older patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.8) had lower odds of endorsing this domain compared with younger participants (p=0.0003). Once again, Australian-born patients had lower odds of endorsing this domain (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.6; p=0.0003). Marginally non-significantly lower odds were also found in socioeconomic group 2 (OR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) and group 3 (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) compared with the lowest socioeconomic group 1 (p=0.0837).

Better services/support to cope with changes to my relationships: older patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.1; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.4) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.4) had lower odds of endorsing this domain compared with younger participants (p<0.0001). Once again, Australian-born patients had lower odds of endorsing this domain (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5; p=0.0001). Patients with clinically significant levels of depression had higher odds of endorsing this domain (OR=7.2; 95% CI 2.3 to 22.5; p=0.0007).

Better services/advice to assist me with practical concerns: older patients aged 60–69 years (OR=0.1; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.3) and aged 70 or over (OR=0.3; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.6) had lower odds of endorsing this domain compared with younger participants (p<0.0001). Australian-born patients also had lower odds of endorsing this domain (OR=0.5; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8; p=0.0070).

Proportion of patients endorsing multiple domains where better care would have improved their well-being

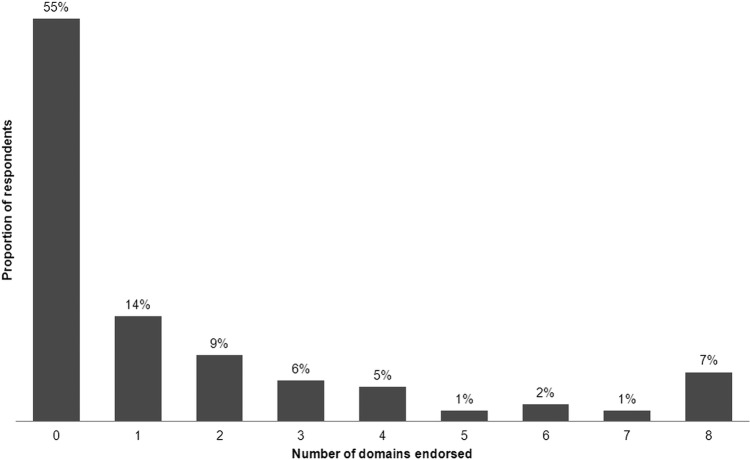

Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents endorsing none, one and multiple domains where better care would have improved their well-being. Overall, 31% of respondents (n=107) endorsed multiple domains where they agreed or strongly agreed that their well-being could have been improved by better care.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents endorsing 0–8 domains in which better care would have greatly improved their well-being.

For 55% of participants, it was perceived that improvement in well-being would not have resulted from better care in any of the examined domains. Fourteen per cent of participants identified only one domain where better care would have greatly improved their well-being. Table 4 shows the results of analyses examining factors associated with the perception that well-being could have been improved by better care in multiple (2 or more) domains. It can be seen that compared with the younger age group (18–49 years), being aged 60 years or over was associated with significantly lower odds of endorsing multiple domains as requiring improvement. Additionally, relative to patients not born in Australia, those who were Australian-born had significantly lower odds of endorsing multiple domains in which well-being would have been improved by better care. Outpatients living with a partner had significantly lower odds of identifying multiple domains where better care would have greatly improved their well-being. There were significantly higher odds of endorsing multiple domains among outpatients with a likely presence of anxiety.

Table 4.

Demographic, disease and HADS associations with endorsement of multiple domains as requiring improvement†

| Multiple domains endorsed n (%) | LR χ2, p value | LR χ2, p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI)‡ | Adjusted OR (95% CI)‡ | ||

| Hospital | 5.0, p=0.1752 | 2.9, p=0.4002 | |

| Site 1 | 36 (36%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Site 2 | 22 (23%) | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.0) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) |

| Site 3 | 23 (32%) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.8) |

| Site 4 | 26 (34%) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| Age category | 35.9, p<0.0001 | 28.9, p<0.0001**** | |

| 18–49 years | 36 (51%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–59 years | 34 (46%) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) |

| 60–69 years | 20 (18%) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| 70 years plus | 17 (19%) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.5) |

| Sex§ | 2.5, p=0.1159 | ||

| Male | 48 (27%) | 1.0 | |

| Female | 59 (35%) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.3) | |

| Cancer type§ | 3.8, p=0.1469 | ||

| Breast | 31 (33%) | 1.0 | |

| Prostate | 16 (22%) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) | |

| Other cancer types¶ | 60 (34%) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | |

| Second diagnosis or recurrence | 1.0, p=0.3123 | ||

| No | 81 (33%) | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 26 (27%) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | |

| Born in Australia | 8.5, p=0.0037 | 5.4, p=0.0205* | |

| No | 47 (42%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 60 (26%) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.3, p=0.5758 | ||

| Low | 5 (22%) | 1.0 | |

| Medium | 8 (16%) | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.4) | |

| High | 59 (22%) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.9) | |

| Usual place of residence | 0.3, p=0.5758 | ||

| Major city | 87 (32%) | 1.0 | |

| Regional or rural | 19 (28%) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.5) | |

| Living with partner | 5.2, p=0.0224 | 3.9, p=0.0481* | |

| No | 50 (38%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 57 (27%) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) |

| Clinically significant anxiety†† | 10.4, p=0.0013 | 4.3, p=0.0383* | |

| No | 82 (28%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 25 (52%) | 2.8 (1.5 to 5.2) | 2.1 (1.0 to 4.1) |

| Clinically significant depression§†† | 5.7, p=0.0167 | ||

| No | 97 (30%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 10 (59%) | 3.3 (1.2 to 9.0) | |

| Completed radiation therapy appointments | 0.02, p=0.8893 |

Note: Observations within each variable may not add to the total due to missing values.

*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001 ****p<0.0001

†p-values for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test were between 0.2 and 0.9 for specific domain models; and was 0.1 for the multiple domain model (Table 4 description, line 755).

‡Reported p-values are from the Likelihood ratio test (Table 4, Column 3 and 4 headers).

§Eliminated during backwards stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis.

¶Including brain, colorectal, head and neck, lung, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and other cancer types.

††Assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Discussion

In which domains would better care greatly improve well-being for the most patients?

For each of the eight domains of care assessed, between 12% and 22% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their well-being would have greatly improved with better care. One-fifth or more agreed that improvements to the following domains would have improved their care: better information and communication about my cancer and care (22%); better emotional and/or spiritual support (22%); better management of physical symptoms (21%); better services information and support for friends/family (21%) and better services/advice to assist with practical concerns (20%). Overall, these frequencies were lower than identified in comparable domains in recent international studies of experiences of care in patients with cancer in Australia, New Zealand, British Colombia, Canada and Europe.11 13 18 35 36 This discrepancy may be a consequence of the differences in measures. Although past measures have assessed experiences of care or unmet need, they have not assessed the impact that patients perceive better care in these patient-centred domains would have on their well-being. Alternatively, the discrepancies between findings may be a result of improved delivery of patient-centred care over time.

Characteristics associated with endorsing each domain of patient-centred care

Country of birth

Australian-born patients had lower odds of endorsing each of the assessed domains of patient-centred care. It may be that Australian-born patients perceive that they are receiving better care than migrants. Alternatively, it may be that Australian-born patients have lower expectations of care and of the degree to which their well-being would be improved by better care.37 Linguistic and cultural barriers to patient perceptions of high-quality healthcare have been previously identified, highlighting the need for responsiveness to cultural background for optimal healthcare delivery.37 Although the current research was limited to patients with adequate English to complete the survey, there has been increased research attention on some of these challenges faced by people with cancer from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Australia.38 39

Age group

Older age was associated with lower odds of endorsing a need for improvement in all domains of patient-centred care, with the exception of management of physical symptoms and staff approachability and respect for the patient. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting that older age is associated with higher overall patient satisfaction ratings40 and that older patients undergoing radiation treatment have lower information needs.24 It may be that older patients perceive pain management and interpersonal care as a traditional role of the doctor, leading to similar perceptions about the need for improvement in these domains as held by younger age groups.

HADS classified depression

Patients with HADS classified depression had higher odds of endorsing the following three domains than non-depressed respondents: information and communication about cancer and care; emotional and spiritual support and support with changes to relationships. A diagnosis of chronic disease with comorbid depression has previously been associated with perceptions of poor doctor–patient communication.41 This may be because depressive symptoms such as negative affect may make interactions with healthcare providers more strained and less effective than for non-depressed patients.42 43 Alternatively, it may be that there are patient recall difficulties arising from depressive symptoms such as poor concentration, leading to negative patient perceptions of information provision and communication.41

Socioeconomic status

Higher socioeconomic groups were found to have marginally significantly lower odds of endorsing issues relating to getting access to care when required. Patients from higher SES areas may be more likely to live in wealthier urban areas that are closer to healthcare facilities, and therefore have less difficulties with access.44 Given Australia's dispersed population, access to cancer care service delivery can be challenging for patients from lower SES areas, particularly those in rural and regional areas. This is particularly the case for accessing RT treatment, which is only available in metropolitan centres and very few major regional centres.45

Multiple domains of patient-centred care: characteristics of particularly vulnerable groups

Overall, 31% of patients indicated that better care in multiple domains of patient-centred care would have greatly improved their well-being. Older patients had lower odds of reporting that improvements in their care needed multiple domains of care. This finding has been frequently reported in patient satisfaction research.40 It has been suggested that this may reflect differences in the expectations or preferences of care of older people compared with younger people.17 Consistent with the findings across the individual domains of care, patients born in Australia had lower odds of endorsing multiple domains where better care would have greatly improved their well-being. This is consistent with findings of lower patient satisfaction that have been reported in migrant groups in international settings.37

A significant trend towards having lower odds of reporting improvements in their care was seen in those respondents living with a partner. Spranger et al19 reported that the quality of life in individuals with chronic disease was higher among those with a partner. Family members and carers may play an important role in assisting patients to navigate the healthcare system and may advocate on the patient's behalf.46 Patients’ self-management skills may also be complemented by having a support person47; however, these findings warrant further exploration in cancer settings.48

As expected, an association was found between clinically significant anxiety levels and patients’ perceptions that their well-being could be improved by better care across multiple patient-centred domains. This is consistent with findings suggesting that individuals suffering from elevated levels of anxiety may be more likely to be critical of the healthcare system.49 Alternatively, anxiety may affect interactions with healthcare providers and the effectiveness of help-seeking behaviours, resulting in the receipt of poorer care across multiple domains. This finding suggests that there is a need to identify these patients in clinical practice and reduce their perceived room for improvement in well-being by alleviating their anxiety and improving their perceptions of care.50 There have been some partially successful intervention studies conducted in radiotherapy settings 51 52 and more generally3 that have aimed to improve patient-centredness of care.

Strengths and limitations

The current study achieved a high consent rate compared with recent research examining cancer outpatient satisfaction with care,13 and to the best of our knowledge, it is also the first large study to assess patient-centred care in RT outpatients.53 Heterogeneous cancer sites and stages were included to provide clinics with information about which patient groups may be missing out on elements of patient-centred care. The quality of care measure was developed following extensive pilot testing and with reference to the literature, and the domains have been supported by a recent qualitative study with radiation oncology patients.53 Therefore, it appears to have face validity as well as internal reliability. However, further examination of its psychometric properties is needed. Demographic information was collected via patient self-report. While the accuracy of this method has been questioned,54 it has been shown to produce reliable responses for these demographic variables,55 and is a cost-effective and feasible way of collecting these data.

It should also be noted that owing to extended pilot testing and low survey completion rates, our final sample size was smaller than planned. However, given that the proportion of patients perceiving the need for better care in each domain was lower than expected, we were still able to obtain prevalence estimates with 95% CIs within ±5% of the point estimate, and detect differences of approximately 15% in characteristics between those who did and did not perceive the need for better care in each domain of care with 80% power and 5% significance level.

Conclusions

Thirty-one per cent of respondents identified that better care across multiple domains would have greatly improved their well-being. ‘Information and education’, ‘emotional and spiritual support’, ‘management of physical symptoms’ and ‘involvement of friends and family’ were the four domains most commonly identified where better care would have increased respondent well-being. Older patients and patients born in Australia had significantly lower odds of identifying multiple domains of patient-centred care where better care would have improved their well-being. This suggests that younger patients and migrants to Australia appear to be more likely to identify that better care would be of benefit to their well-being. Further investigation of how these factors interact with well-being and the provision of patient-centred care may assist in developing targeted interventions to improve outcomes for these groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sundresan Naicker, Jay House, Kelauren Barry and Ryan Courtney for their assistance with data collection for this study. We would also like to thank Dr Patrick McElduff, Mr Daniel Barker and Mr Michael Fitzgerald for their guidance with statistical analysis. We would also like to thank the staff and patients at the participating radiation oncology treatment centres.

Footnotes

Contributors: LM was involved in the conception of the manuscript, study design, coordination of patient recruitment and management of data collection, statistical analysis and data interpretation. MC was involved in the conception of the manuscript, study design, coordination of patient recruitment and data interpretation. RS-F initiated the manuscript conception, and was involved in the study design, coordination of patient recruitment and data interpretation. CD'E was involved in study design and provided statistical support including data interpretation for the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript drafting and revisions for important intellectual content, and approved of this final version of the manuscript.

Funding: LMs PhD candidature is supported by a University of Newcastle School of Medicine and Public Health Professor Jill Cockburn Scholarship in Health Behaviour. MC is supported by a Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) Fellowship. The touchscreen computer resources and patient recruitment costs were covered by a 2009 University of Newcastle Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour research grant.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by a University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee and the New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee. Relevant institutional approvals were also obtained for participating hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Chassin MR, Galvin RW, the National Roundtable on Health Care Quality The urgent need to improve health care quality. JAMA 1998;280:1000–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewin S, Skea Z, Entwistle VA, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001(4): CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. The diabetes care from diagnosis research team. BMJ 1998;317:1202–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, et al. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1489–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arah OA, Westert GP, Hurst J, et al. A conceptual framework for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18 (Suppl 1):5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groene O, Skau JKH, Frølich A. An international review of projects on hospital performance assessment. Int J Qual Health Care 2008;20:162–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eden J, Simone JV, eds. Assessing the quality of cancer care: an approach to measurement in Georgia. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, et al. Patients’ experiences and satisfaction with health care: results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:335–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouwens M, Hermens R, Hulscher M, et al. Development of indicators for patient-centred cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:121–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J. Through the patients’ eyes. Understanding and promoting patient-centred care. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancer Institute NSW New South Wales cancer patient satisfaction survey 2008. Sydney: Cancer Institute NSW, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uphoff EPMM, Wennekes L, Punt CJA, et al. Development of generic quality indicators for patient-centered cancer care by using a RAND modified delphi method. 2012;35:29–37 doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e318210e3a2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ 2001;322:1240–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, et al. Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Cancer 2000;88:217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan GJ, Counte MA, Cella DF, et al. An analysis of the impact of demographic, clinical, and social factors on health-related quality of life. Value Health 1999;2:308–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Essen L, Larsson G, ÖBerg K, et al. ‘Satisfaction with care’: associations with health-related quality of life and psychosocial function among Swedish patients with endocrine gastrointestinal tumours. Eur J Cancer Care 2002;11:91–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprangers MAG, De Regt EB, Andries F, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:895–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotay CC, Holup JL, Pagano I. Ethnic differences in quality of life among early breast and prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2002;11:103–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halkett GK, Kristjanson LJ, Lobb E, et al. Information needs and preferences of women as they proceed through radiotherapy for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2012;86:396–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison J, Young J, Price M, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:1117–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, et al. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment. Cancer 2005;104:1129–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeguers M, De Haes HCJM, Zandbelt LC, et al. The information needs of new radiotherapy patients: how to measure? Do they want to know everything? And if not, why? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:418–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douma KL, Koning CE, Zandbelt L, et al. Do patients’ information needs decrease over the course of radiotherapy? Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2167–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siekkinen M, Laiho R, Ruotsalainen E, et al. Quality of care experienced by Finnish cancer patients during radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008;17:387–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandoval GA, Brown AD, Sullivan T, et al. Factors that influence cancer patients’ overall perceptions of the quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson BW. Touch-screen versus paper-and-pen questionnaires: effects on patients’ evaluations of quality of care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2006;19:328–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newell S, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. Are touchscreen computer surveys acceptable to medical oncology patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 1997;15:37–46 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrmann C. International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale-a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorey S, Greer S, Watson M, et al. The factor structure and factor stability of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with cancer. Br J Psychiatry 1991;158:225–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyes A, Newell S, Girgis A. Rapid assessment of psychosocial well-being: are computers the way forward in a clinical setting? Qual Life Res 2002;11:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Australian Bureau of Statistics SEIFA: Socio-economic indexes for areas. Secondary SEIFA: Socio-economic indexes for areas. 2008. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Seifa_entry_page (accessed Oct 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien I, Britton E, Sarfati D, et al. The voice of experience: results from cancer control New Zealand's first national cancer care survey. N Z Med J 2010;123:10–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson DE, Mooney D, Peterson S. Patient experiences with ambulatory cancer care in British Columbia, 2005/06: UBC Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, 2007

- 37.Harmsen JAM, Bernsen RMD, Bruijnzeels MA, et al. Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:155–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butow P, Sze M, Dugal-Beri P, et al. From inside the bubble: migrants’ perceptions of communication with the cancer team. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:281–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchison D, Butow P, Sze M, et al. Prognostic communication preferences of migrant patients and their relatives. Psychooncology 2012;21:496–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaipaul CK, Rosenthal GE. Are older patients more satisfied with hospital care than younger patients? J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schenker Y, Stewart A, Na B, et al. Depressive symptoms and perceived doctor-patient communication in the Heart and Soul study. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:550–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall JA, Horgan TG, Stein TS, et al. Liking in the physician–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall JA, Roter DL, Milbrun MA, et al. Patients’ health as a predictor of physician and patient behavior in medical visits: a synthesis of four studies. Med Care 1996;34:1205–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul C, Carey M, Anderson A, et al. Cancer patients’ concerns regarding access to cancer care: perceived impact of waiting times along the diagnosis and treatment journey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:321–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann F, Hedges A, Hunt B. Barriers to rural patients electing to have radiotherapy. Special report: radiotherapy Summit 2000. Cancer Council Aust 2002;26:177–8 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sales E. Family burden and quality of life. Qual Life Res 2003;12 (Suppl 1):33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark PC, Dunbar SB. Family partnership intervention: a guide for a family approach to care of patients with heart failure. AACN Clin Issues 2003;14:467–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rijken M, Jones M, Heijmans M, et al. Supporting self-management. In: Nolte E, McKee M, eds. Caring for people with chronic conditions: a health system perspective. Berkshire: Open University Press, 2008:116–42 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Factors affecting patient and clinician satisfaction with the clinical consultation: can communication skills training for clinicians improve satisfaction? Psychooncology 2003;12:599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin H-R, Bauer-Wu SM. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halkett G, Merchant S, Jiwa M, et al. Effective communication and information provision in radiotherapy—the role of radiation therapists. J Radiother Pract 2010;9:3–16 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halkett GK, Schofield P, O'Connor M, et al. Development and pilot testing of a radiation therapist-led educational intervention for breast cancer patients prior to commencing radiotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2012;8:e1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nijman JL, Sixma H, Triest BV, et al. The quality of radiation care: the results of focus group interviews and concept mapping to explore the patient's perspective. Radiother Oncol 2012;102:154–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manjer J, Merlo J, Berglund G. Validity of self-reported information on cancer: determinants of under- and over-reporting. Eur J Epidemiol 2004;19:239–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergmann MM, Calle EE, Mervis CA, et al. Validity of self-reported cancers in a prospective cohort study in comparison with data from state cancer registries. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:556–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.