Abstract

Objective

The objective of the study is to evaluate short-term complications after laparoscopic (LC) or open cholecystectomy (OC) in patients with gallstones by using linked hospital discharge data.

Design

Population-based cohort study.

Setting

Data were obtained from the Regional Hospital Discharge Registry Lazio Region in Central Italy (around 5 million inhabitants) in 2007–2008.

Participants

All patients admitted to hospitals of Lazio with symptomatic gallstones (International Classification of disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)=574) who underwent LC (ICD-9-CM 51.23) or OC (ICD-9-CM 51.22).

Outcome measures

(1)‘30-day surgical-related complications’ defined as any complication of the biliary tract (including postoperative infection, haemorrhage or haematoma or seroma complicating a procedure, persistent postoperative fistula, perforation of bile duct and disruption of wound). (2) ‘30-day systemic complications’ defined as any complications of other organs (including sepsis, infections from other organs, major cardiovascular events and selected adverse events).

Results

13 651 patients were included; 86.1% had LC, 13.9% OC. 2.0% experienced surgical-related complications (SRC), 2.1% systemic complications (SC). The OR of complications after LC versus OC was 0.60 (p<0.001) for SRC and 0.52 (p<0.001) for SC. In relation to SRC, the advantage of LC was consistent across age categories, severity of gallstones and previous upper abdominal surgery, whereas there was no advantage among people with emergency admission (OR=0.94, p=0.764). For SC, no significant advantage of LC was seen among very old people (OR=0.99, p=0.975) and among those with previous upper abdominal surgery (OR=0.86, p=0.905).

Conclusions

This large observational study confirms that LC is more effective than OC with respect to 30-day complications. Population-based linkage of administrative datasets can enlarge evidence of treatment benefits in clinical practice.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Adverse Events < Therapeutics, Qhepatobiliary Surgery <Uality In Health Care < Health Services Administration & Management, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

The advantage of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) approach for the treatment of gallstones versus open surgery has been shown from randomised controlled trials and observational studies.

The use of linked administrative health records has become one of the most powerful tools in observational studies aimed at comparing treatments.

We compared laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in terms of 30-day complications using routinely collected databases in the Lazio Region (Italy).

Key messages

This population-based cohort study contributes to the enlargement of evidence on the effectiveness of LC in a real-life setting.

In relation to surgical-related complications, the advantage of LC was consistent across age categories, severity of gallstones and previous upper abdominal surgery, while there was no advantage among people with emergency admission.

For systemic complications, no significant advantage of LC was seen among very old people and among those with previous upper abdominal surgery.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Population-based design, 30-day outcomes, large numbers and robustness of analytical procedures are the main strengths.

It contributes to the debate on the complex methodology to estimate the risk of adverse events after surgery using secondary databases to monitor the quality of care.

The use of ICD-9-CM codes in the definition of severity of disease presentation and of complications is a major limitation.

Background

Comparative effectiveness research is becoming central in monitoring real-life impact of treatments and supporting public health decisions.1 2 Although the basic concept of comparing therapies is not new, over the last few years many initiatives have been implemented in several countries to provide large-scale evidence on the benefits and harms of different treatments.3–5 The use of linked administrative health records has become one of the most powerful tools in observational studies aimed at comparing treatments. They include hospital inpatient records, birth and death registrations, outpatient care records, dispensed pharmacy drugs.6–9

In the Lazio Region (around 5 000 000 inhabitants), the P.Re.Val.E. Project (Regional Outcome Evaluation Program) was launched in 2005. Its aims are: to measure the quality of healthcare provided in the Lazio Region, to describe variability of care provision across institutions and populations and to compare the effectiveness of treatments for different medical and surgical conditions.10 11 Over 60 outcome indicators are calculated based on data obtained from record-linkage procedures of different health systems. The results are periodically updated and publicly disseminated with discussion on critical methodological points.

Cholecystectomy is one of the most common abdominal surgical procedures in developed countries. Since its introduction in the late 1980s, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has replaced open cholecystectomy (OC) as the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstones.12 13 Beneficial effects of LC have been demonstrated in studies showing the advantages from real-life settings using secondary databases.9 14–19 In the present study, we aimed at developing a methodology to measure short-term complications after LC or OC using large administrative databases on behalf of the P.Re.Val.E. Second, we tested the hypothesis that the advantages of LC versus OC could vary according to age and clinical patients’ characteristics.

Methods

Source of data

Data were derived from the Lazio Hospital Information System (HIS), which provides information on patients’ demographic data (gender, age, place of birth and place of residence), admission and discharge dates, discharge diagnoses (up to 6) and medical procedures or surgical interventions ((up to 6) according to the International Classification of disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), status at discharge (alive, dead or transferred to another hospital), ward(s) of stay, date(s) of inhospital transfer, and a regional code corresponding to the admitting facility for patients discharged from all public and private hospital of the Lazio Region).

Study population

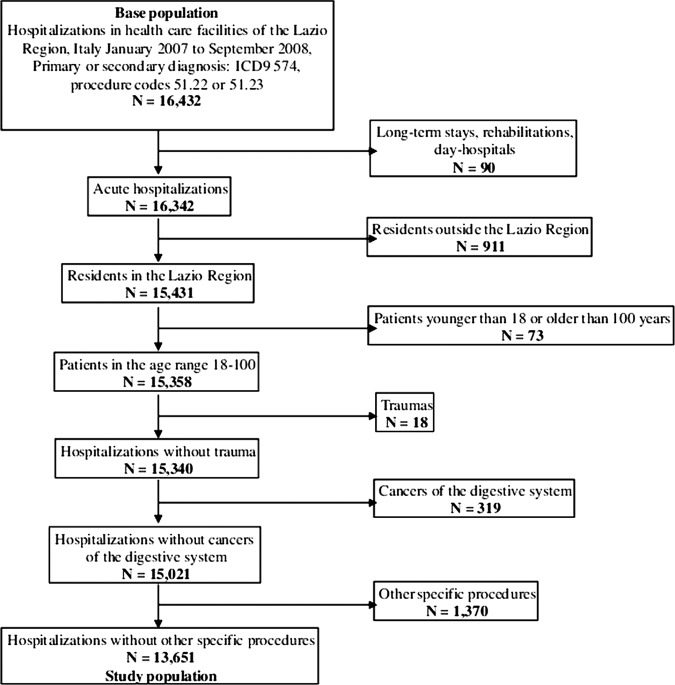

All hospital admissions with a primary or secondary diagnosis of gallstones (ICD-9-CM=574) and a procedure code of cholecystectomy (ICD-9-CM 51.22, 51.23), which occurred in private and public hospitals of the Lazio Region between January 2007 and September 2008, were included, making a total of 16 432 cases (age 18+ years). We a priori decided not to include codes for partial cholecystectomy (ICD-9-CM 51.21 and 51.24) to increase the specificity of our exposure. Information was retrieved from the HIS. In order to increase the case specificity, several exclusion criteria were applied including long-term hospitalisations, rehabilitations, day-hospitals, hospitalisations for delivery or trauma or cancer, hospitalisations with abdominal surgical procedures other than cholecystectomy. The final population consisted of 13 651 individuals (figure 1). See the online supplementary data (Part 1) for details on the exclusion criteria and ICD-9-CM codes. According to the Regional Law, the present study, which was based on anonymous computer records from health information systems, did not require ethical approval.

Figure 1.

Selection of the study population.

Patient-level risk factors

The following characteristics were considered for each patient: age (<70; 70–79; ≥80 years old); gender; severity of gallstones: it was classified as low (not complicated), moderate (presence of cholecystitis or biliary tract obstruction) and high (presence of both inflammation and obstruction of the biliary tract); previous upper abdominal surgery (based on previous 2-year hospitalisations); comorbidities (based on previous 2-year hospitalisations) following validated algorithms20 21; type of admission: either elective or emergency. See the online supplementary data (Parts 2–4) for details on the ICD-9-CM codes. The choice of cut-off for age category was based on previous studies to distinguish adult and old people.22–24

Outcomes

We identified various complications within 30 days after the intervention and grouped them in two categories: (1) ‘30-day surgical-related complications’ defined as any complication of the biliary tract (including postoperative infection, haemorrhage or haematoma or seroma complicating a procedure, persistent postoperative fistula, perforation of bile duct, disruption of wound); (2) ‘30-day systemic complications’ defined as any complications of other organs (including sepsis, infections from other organs, major cardiovascular events and selected adverse events). The complete list of complications with ICD-9-CM codes is reported in the online supplementary data (Part 5). Among the various complications, we included some conditions reported in the list of Patient Safety Indicators developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, while other items were specifically created on the basis of scientific literature on digestive surgery.14–19 25 26 Depending on the type of complication, some ICD-9-CM codes were searched in the index admission as well as the following ones in the 30-day period after the surgery, whereas others were searched only in later hospitalisations. For example, peritonitis or acute pancreatitis was not counted as complications when reported in the index admission. See the online supplementary data (Part 5) for details on the ICD-9-CM codes. In case of a subsequent hospitalisation occurred out of the study area (eg, in a region other than Lazio), we obtained information through record linkage procedure between hospital information systems. Because of the short follow-up time, this happened in a minimal proportion of cases (0.1%). The outcome variables were ‘30-day surgical-related complications’ and ‘30-day systemic complications’; they were coded ‘1’ if at least one of the complications within the group was present and ‘0’ if none was recorded.

Type of cholecystectomy

We defined “type of cholecystectomy” as the exposure variable (LC vs OC). In case of ICD-9-CM codes for both LC and OC (5%), the patient was considered to be exposed to the open surgical procedure. We could not use the specific ICD-9 code for a case converted from LC to OC (ICD-9-CM code V 64.41) because it was highly under-reported in our region in the study period.

Statistical analysis

Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to estimate the relative risk of 30-day complications (either ‘surgical-related’ or ‘systemic’) after LC versus OC, adjusting for demographical and clinical risk factors. The two outcome variables were analysed separately. The predictive model was made of two sets of predictors: (1) variables ‘a priori’ chosen as confounders (age, gender, severity of gallstones, previous upper abdominal surgery and type of admission); (2) variables empirically tested (comorbidities) which were selected using iterative stepwise statistical procedures.27 Once the ‘best’ predictive model was identified for each of the two outcomes, the variable ‘type of cholecystectomy’ was included, and the adjusted OR of LC versus open surgery was estimated, with a corresponding 95% CI and p value.

In order to test the hypothesis of an effect modification by age, relative risk estimates for the age groups were derived by adding an interaction term between the age group and the treatment variable in the final multivariate logistic model. We obtained the OR of laparoscopic versus open surgery within each age stratum by adding the corresponding interaction term coefficients. This was accomplished by adding a coefficient from the reference category and another coefficient from the age stratum of interest, and by computing the corresponding standard error from the corresponding terms of the variance–covariance matrix. Similarly, effect modification was tested with regard to the severity of cholelithiasis, previous upper abdominal surgery and type of admission. The corresponding tests of heterogeneity of the stratum-specific risk estimates were computed.

Sensitivity analyses were performed. First, in order to guarantee adequate control of confounding factors, we identified and adjusted for all the individual factors associated with the treatment, within the propensity adjustment framework.28 This procedure is a two-step technique: (1) it estimates the a priori probability of exposure for each individual, based on clinical and demographic characteristics and (2) it standardises them in the association between treatment and the study outcome. The individual factors related to the exposure in the present study include age, gender, severity of cholelithiasis, previous upper abdominal surgery, type of admission, cardiocirculatory disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or respiratory failure, chronic nephropathy and chronic disease of the liver or pancreas. Second, to take into account the potential heterogeneous experience in laparoscopic surgery across different hospitals because of the patients’ clustering within a single institution, we performed a multilevel regression model with random intercepts for hospitals.29

All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS Software V.8.0 (SAS Institute, Inc SAS/STAT software).

Results

A description of the study population, overall and by cholecystectomy procedure, is presented in table 1. Over 80% of the patients were younger than 70 years, and moderate-to-high severity of the gallstones was diagnosed for 61.7%. As compared with patients undergoing LC, those who underwent OC were more likely to be elderly men with a more severe baseline disease and more chronic conditions. Furthermore, they were operated in emergencies in most of the cases (52.4%), whereas LC was performed in elective hospitalisations much more frequently (73.9%).

Table 1.

Study population, overall and by cholecystectomy procedure: distribution by age, gender, severity of cholelitiasis, previous upper abdominal surgery, type of admission, comorbidities—Lazio Region, Italy, January 2007–September 2008

| Patient characteristics | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Open cholecystectomy |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 11 752 | 86.1 | 1899 | 13.9 | 13 651 | 100.0 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <70 | 9913 | 84.4 | 1162 | 61.2 | 11 075 | 81.1 |

| 70–79 | 1543 | 13.1 | 485 | 25.5 | 2028 | 14.9 |

| ≥80 | 296 | 2.5 | 252 | 13.3 | 548 | 4.0 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 4349 | 37.0 | 979 | 51.6 | 5328 | 39.0 |

| Women | 7403 | 63.0 | 920 | 48.4 | 8323 | 61.0 |

| Severity of cholelitiasis | ||||||

| Low | 4767 | 40.6 | 470 | 24.7 | 5237 | 38.4 |

| Moderate | 6456 | 54.9 | 1200 | 63.2 | 7656 | 56.1 |

| High | 529 | 4.5 | 229 | 12.1 | 758 | 5.6 |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | ||||||

| No | 11714 | 99.7 | 1867 | 98.3 | 13581 | 99.5 |

| Yes | 38 | 0.3 | 32 | 1.7 | 70 | 0.5 |

| Type of admission | ||||||

| Elective | 8690 | 73.9 | 903 | 47.6 | 9593 | 70.3 |

| Emergency | 3062 | 26.1 | 996 | 52.4 | 4058 | 29.7 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cancer | 232 | 2.0 | 75 | 3.9 | 307 | 2.2 |

| Diabetes | 268 | 2.3 | 100 | 5.3 | 368 | 2.7 |

| Obesity | 115 | 1.0 | 25 | 1.3 | 140 | 1.0 |

| Blood disease | 146 | 1.2 | 62 | 3.3 | 208 | 1.5 |

| Hypertension | 842 | 7.2 | 247 | 13.0 | 1089 | 8.0 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 246 | 2.1 | 107 | 5.6 | 353 | 2.6 |

| Past coronary revascularisation | 63 | 0.5 | 22 | 1.2 | 85 | 0.6 |

| Heart failure | 47 | 0.4 | 41 | 2.2 | 88 | 0.6 |

| Other heart disease | 158 | 1.3 | 76 | 4.0 | 234 | 1.7 |

| Conduction disorders or dysrhythmia | 250 | 2.1 | 95 | 5.0 | 345 | 2.5 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 146 | 1.2 | 74 | 3.9 | 220 | 1.6 |

| Vascular disease | 91 | 0.8 | 38 | 2.0 | 129 | 0.9 |

| COPD or respiratory failure | 189 | 1.6 | 84 | 4.4 | 273 | 2.0 |

| Chronic nephropathy | 68 | 0.6 | 46 | 2.4 | 114 | 0.8 |

| Chronic disease of the liver or pancreas | 219 | 1.9 | 70 | 3.7 | 289 | 2.1 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2 reports the relationship between demographic and clinical variables and the occurrence of complications. The adjusted risk of systemic complications increased with age and was much higher in patients with more severe baseline gallstones, whereas no clear age or severity-related differences in risk emerged with regard to surgical-related 30-day complications, once other cofactors were taken into account. Women were less likely to experience both types of complications. Having had a previous intervention on the upper digestive system seemed to enhance the risk of both surgical-related and systemic complications, though results were not statistically significant owing to small power. Finally, the risk of both types of complications was more evident in emergencies as opposed to scheduled interventions. Surgical-related complications were higher among individuals with obesity, blood disease, stroke or chronic nephropathy, whereas systemic complications were associated with blood diseases, ischaemic heart disease, conduction disorders or dysrhythmias, COPD or respiratory failure, chronic nephropathy and chronic diseases of the liver or pancreas.

Table 2.

Factors related to the incidence of 30-day complications after cholecystectomy. OR crude and adjusted, p values—Lazio Region, Italy, January 2007–September 2008 (N=13 651)

| Patient characteristics | 30-Day surgical-related complications (N=278, 2.0%) |

30-Day systemic complications (N=280, 2.1%) |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | ORcrude | 95% CI | p Value | ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | Per cent | ORcrude | 95% CI | p Value | ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | |||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| <70 | 1.8 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.5 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| 70–79 | 2.9 | 1.62 | 1.21 | 2.18 | 0.001 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 1.83 | 0.048 | 3.9 | 2.68 | 2.04 | 3.52 | 0.000 | 2.01 | 1.51 | 2.67 | 0.000 |

| ≥80 | 3.3 | 1.84 | 1.13 | 3.00 | 0.015 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 2.03 | 0.475 | 7.1 | 5.13 | 3.58 | 7.36 | 0.000 | 2.79 | 1.87 | 4.14 | 0.000 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 2.5 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 2.6 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Women | 1.7 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.002 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.96 | 0.022 | 1.7 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.84 | 0.001 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 1.02 | 0.070 |

| Severity of cholelithiasis | ||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 1.9 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.2 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Moderate | 2.0 | 1.08 | 0.84 | 1.40 | 0.538 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.24 | 0.733 | 2.2 | 1.84 | 1.38 | 2.46 | 0.000 | 1.55 | 1.15 | 2.08 | 0.004 |

| High | 3.7 | 2.03 | 1.32 | 3.14 | 0.001 | 1.43 | 0.91 | 2.24 | 0.122 | 6.2 | 5.30 | 3.59 | 7.83 | 0.000 | 3.40 | 2.26 | 5.11 | 0.000 |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 2.0 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 2.0 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 5.7 | 2.94 | 1.07 | 8.13 | 0.037 | 2.29 | 0.81 | 6.51 | 0.119 | 4.3 | 2.15 | 0.67 | 6.88 | 0.197 | 1.72 | 0.52 | 5.74 | 0.376 |

| Type of admission | ||||||||||||||||||

| Elective | 1.6 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.5 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Emergency | 3.0 | 1.85 | 1.45 | 2.35 | 0.000 | 1.66 | 1.29 | 2.13 | 0.000 | 3.4 | 2.34 | 1.85 | 2.97 | 0.000 | 1.64 | 1.27 | 2.11 | 0.000 |

| Comorbidities (presence of the condition) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 2.6 | 1.30 | 0.64 | 2.64 | 0.476 | – | – | – | – | 3.6 | 1.81 | 0.98 | 3.34 | 0.059 | – | – | – | – |

| Diabetes | 3.3 | 1.65 | 0.92 | 2.97 | 0.095 | – | – | – | – | 4.4 | 2.24 | 1.34 | 3.75 | 0.002 | – | – | – | – |

| Obesity | 5.0 | 2.57 | 1.19 | 5.55 | 0.016 | 2.35 | 1.29 | 2.13 | 0.034 | 4.3 | 2.16 | 0.95 | 4.94 | 0.067 | – | – | – | – |

| Blood disease | 5.8 | 3.03 | 1.67 | 5.50 | 0.000 | 2.09 | 1.11 | 3.93 | 0.022 | 7.7 | 4.16 | 2.46 | 7.03 | 0.000 | 1.96 | 1.09 | 3.51 | 0.024 |

| Hypertension | 2.9 | 1.46 | 1.00 | 2.13 | 0.050 | – | – | – | – | 4.0 | 2.20 | 1.58 | 3.05 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.8 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 2.69 | 0.286 | – | – | – | – | 7.4 | 4.08 | 2.69 | 6.20 | 0.000 | 1.74 | 1.09 | 2.78 | 0.020 |

| Past coronary revascularization | 2.4 | 1.16 | 0.28 | 4.74 | 0.836 | – | – | – | – | 9.4 | 5.08 | 2.43 | 10.62 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – |

| Heart failure | 2.3 | 1.12 | 0.27 | 4.57 | 0.875 | – | – | – | – | 4.6 | 2.29 | 0.83 | 6.29 | 0.107 | – | – | – | – |

| Other heart disease | 3.4 | 1.72 | 0.84 | 3.52 | 0.136 | – | – | – | – | 6.8 | 3.66 | 2.17 | 6.16 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – |

| Conduction disorder or dysrhythmia | 4.1 | 2.09 | 1.21 | 3.62 | 0.008 | – | – | – | – | 7.0 | 3.81 | 2.47 | 5.88 | 0.000 | 1.73 | 1.07 | 2.79 | 0.025 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5.9 | 3.12 | 1.76 | 5.54 | 0.000 | 1.98 | 1.09 | 3.60 | 0.025 | 7.7 | 4.19 | 2.52 | 6.98 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – |

| Vascular disease | 0.8 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 2.68 | 0.328 | – | – | – | – | 8.5 | 4.59 | 2.45 | 8.62 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – |

| COPD or respiratory failure | 2.6 | 1.27 | 0.60 | 2.72 | 0.534 | – | – | – | – | 7.7 | 4.22 | 2.66 | 6.70 | 0.000 | 2.02 | 1.23 | 3.31 | 0.006 |

| Chronic nephropathy | 9.7 | 5.31 | 2.82 | 10.00 | 0.000 | 3.24 | 1.65 | 6.36 | 0.001 | 10.5 | 5.82 | 3.16 | 10.72 | 0.000 | 2.27 | 1.15 | 4.46 | 0.018 |

| Chronic disease of the liver or pancreas | 3.5 | 1.75 | 0.92 | 3.33 | 0.087 | – | – | – | – | 4.8 | 2.51 | 1.45 | 4.35 | 0.001 | 1.97 | 1.11 | 3.48 | 0.020 |

Table 3 shows the relationship between the types of cholecystectomy and outcomes, adjusted for the risk factors identified in table 2. We report results of the advantage of LC versus OC (OR, 95% CI) in the cohort and in each stratum of the variables tested in the models with interaction terms. The incidence of ‘30-day surgical-related complications’ and ‘30-day systemic complications’ was 2.0% and 2.1%, respectively. The OR of surgical related complications for patients who underwent LC as compared to patients with OC was 0.60 (p<0.001). The corresponding figure for systemic complications was 0.52 (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Association between the type of cholecystectomy and 30-day complications: OR and p values from a crude model, risk-adjusted model and models with interaction with the age group, severity of cholelithiasis, previous upper abdominal surgery and type of admission; p value of heterogeneity of the strata-specific estimates—Lazio Region, Italy, January 2007—September 2008

| Per cent | ORcrude | 95% CI | p Value | ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | phet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day surgical-related complications: N=278, %=2.0 | ||||||||||

| Open cholecystectomy | 3.9 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 1.7 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 0.000 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.80 | 0.001 | – |

| Age (years) | 0.917 | |||||||||

| <70 | 1.8 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.71 | 0.000 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.012 | – |

| 70–79 | 2.9 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.76 | 0.003 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.043 | – |

| ≥80 | 3.3 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 1.12 | 0.082 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 1.38 | 0.184 | – |

| Severity of cholelithiasis | 0.053 | |||||||||

| Low | 1.9 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.61 | 0.000 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.003 | – |

| Moderate | 2.0 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.005 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 1.16 | 0.224 | – |

| High | 3.7 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.000 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.004 | – |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | 0.654 | |||||||||

| No | 2.0 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.000 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 0.001 | – |

| Yes | 5.7 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 2.64 | 0.256 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 3.69 | 0.388 | – |

| Type of admission | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Elective | 1.6 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.000 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.000 | – |

| Emergency | 3.0 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 1.13 | 0.178 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 1.42 | 0.764 | – |

| 30-Day systemic complications: N=280. %=2.1 | ||||||||||

| Open cholecystectomy | 5.2 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 1.6 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.69 | 0.000 | – |

| Age (years) | 0.136 | |||||||||

| <70 | 1.5 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.000 | – |

| 70–79 | 3.9 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 0.002 | – |

| ≥80 | 7.1 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.37 | 0.309 | 0.99 | 0.50 | 1.94 | 0.975 | – |

| Severity of cholelithiasis | 0.755 | |||||||||

| Low | 1.2 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.000 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.77 | 0.005 | – |

| Moderate | 2.2 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.000 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.77 | 0.001 | – |

| High | 6.2 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.002 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 1.05 | 0.071 | – |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | 0.702 | |||||||||

| No | 2.0 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.000 | – |

| Yes | 4.3 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 4.69 | 0.470 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 10.40 | 0.905 | – |

| Type of admission | 0.545 | |||||||||

| Elective | 1.5 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.50 | 0.000 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 0.000 | – |

| Emergency | 3.4 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.000 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.81 | 0.002 | – |

c There are no 30-day complications in patients with moderately high severity and undergoing laparotomic cholecystectomy

In relation to 30-day surgical-related complications, the protective effect of LC versus OC was consistent across the age category, severity of cholelithiasis and previous upper abdominal surgery, whereas among people with emergency admission, there was no advantage (OR=0.94, p=0.764). Similarly, for systemic complications, the superiority of LC versus OC was consistent, regardless of the level of cholelithiasis severity and elective/emergency admission, but for those 80+ years aged people there was no advantage of LC versus OC (OR 0.99, p=0.975); also, for patients with previous upper abdominal surgery, there was a much weaker advantage (OR=0.86, p=0.905).

When the association between the type of cholecystectomy and 30-day complications was adjusted with the propensity adjustment method, the results were consistent with those obtained with the risk-adjustment procedure (LC vs OC OR=0.61 and OR=0.52, respectively, for the two outcomes). Finally, the results were similar, taking into account the patients’ clustering within different hospitals (data not shown).

Discussion

From this large observational study based on linked administrative health records—taking into account the disomogeneous distribution of factors related to the probability of being offered open surgery—people who end up having an LC have a better short-term prognosis than those who get an OC for the treatment of gallstones. The superiority of the laparoscopic approach in terms of 30-day complications is consistent in different age categories, different severity in disease presentation and history of upper abdominal surgery.

This population-based study contributes to the enlargement of evidence on the effectiveness of LC in a real-life setting by providing an example from the Southern Europe area. It supports the usefulness of observational approaches. The 30-day outcomes linked to admission represent one strength of this study. Despite randomised clinical trials (RCTs) being considered the optimal study design when comparing the efficacy of treatments, observational studies provide a picture of treatment under the usual circumstances of healthcare practice and can also answer the question ‘Does it work in practice?’.3 8 RTCs often have a small sample size and may under-represent vulnerable patient groups, including elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, children and young women, and operate in a highly controlled environment that is far from routine clinical practice. Our study supports the theory that LC is a reliable approach that is safer than OC not only in the old age group—confirming previous findings22 30—but also in the presence of severe disease presentation and in patients with a history of upper digestive system surgery. The beneficial effect of LC in relation to systemic complications tends to be lower in 80+ years aged people in comparison with those in younger age groups, and in patients with emergency admission in comparison to elective admissions in relation to 30-day surgical-related complications. These data add to the evidence on the complex relationship between age and outcomes after surgery.22–24 30

A number of potential biases are present. First of all, people in the two groups of patients analysed are not homogeneous in terms of anaesthesia risk due to a higher frequency of the elderly and more comorbidities in the open group than in the laparoscopic one. When comparing the effect of the two techniques using two different populations, the so-called indication bias may affect study validity.8 31 To limit this problem, we run the propensity adjustment analysis to take into account the different distribution of factors strongly associated with the probability to receive open surgery in the study population. This analytical approach confirmed the advantage of laparoscopic versus open surgery obtained in the main logistic regression analysis. Another critical point is the potential different distribution of laparoscopic experience across surgeons; however, a sensitivity analysis which took this point into account led to similar results. The use of ICD-9-CM codes in the definition of severity of disease presentation and of complications is another major limit. Since discharge abstract data have little insight into clinical details and do not inform on the temporal relationship of the clinical conditions and processes, defining complications is a difficult task.32 In this respect, we tried to improve the accuracy of our measures both by (1) applying a specific coding algorithm with subsequent hospital admissions used to retrieve adverse events and (2) excluding in the ‘count’ of complications specific items if reported in the index only (ie, peritonitis) because of the difficulty in determining whether it was already present at admission. Moreover, we cannot exclude an undernotification of complications—a major limit of our source of data—but it is unlikely that it is influenced by the type of surgery. Another major problem is the potential misclassification of exposure as we were not able to measure the occurrence of conversion of LC to OC. The number of individuals that were switched from LC to OC is low in comparison to the figures documented in other studies, and it may represent a severe source of bias in our study.30 33

Beneficial effects of the laparoscopic approach versus traditional open surgery for the treatment of gallstones come from various randomised controlled trials.34 They found significant shorter hospital stay and quicker convalescence associated with LC but no differences in mortality, complications and operative time between the two procedures. A better trend with the laparoscopic approach, including morbidity and mortality, comes from observational studies. From a surveillance system in eight Swiss hospitals, surgical site infections were less common in the laparoscopic approach in comparison to traditional open surgery (0.5% in LC vs 1.8% in OC).35 Significantly, a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism and surgical site-infections in laparoscopic cases versus open cases was observed in a large administrative dataset-based study in USA.14 15 National estimates for LC in USA showed an increase in LC from 52% in 1991 to 75% in 2000 with a constantly low death rate and a decrease in biliary reconstruction rate over time.16 On the basis of the 1997–2006 trend analysis by the same authors, LC was associated with a low death rate (mean value in the period: 0.52%) while OC was associated with a significantly higher rate (corresponding value: 4.9%).9 In a retrospective study using Medicare beneficiaries, common bile duct (CBD) injury during cholecystectomy was associated with a significant higher risk of death in comparison to cholecystectomy without CBD injury over a 9.2-year follow-up period.17 From a Swiss 1995–2005 hospital database analysis, the incidence rate of bile duct injury after LC was 0.3% and did not change over time.18 The incidence of conversion to OC after LC in all hospitals in England from 2005 to 2006 was examined using Hospital Episode Statistics and recorded (4.6% for elective procedures and 9.4% for emergency procedures).19

Population-based linkage of routinely collected health data represents a precious tool to support large-scale and real-world practice evaluation by measuring specific outcomes and comparing them over time and across populations. Together with results from experimental research settings, the conclusions of research studies evaluating clinical outcomes through data linkage systems should be successfully incorporated into practice by clinicians/surgeons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Roberta Macci and Sandra Magliolo for their support in finding the cited articles, and to Anna Kohn (Azienda Ospedaliera S.Camillo, Rome, Italy) for her precious comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: CAP, MD, DF and NA conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. MS and DF were responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. APB and MD provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by NA, APB and MS and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. MS was responsible for the acquisition of the data and CAP, MD, NA, APB and DF contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Funding: This work was supported by the Regional Health Service, Lazio Region on behalf of P.Re.Val.E. (Regional Outcome Evaluation Program). Lazio Region (Italy) DGR 290/16.05.06. Available at http://www.epidemiologia.lazio.it/prevale11/

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Madigan D, Ryan P. What can we really learn from observational studies? The need for empirical assessment of methodology for active drug safety surveillance and comparative effectiveness research. Epidemiology 2011;22:629–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. JAMA 2012;307:1587–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ)—Effective Health Care Program. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov (accessed May 2012).

- 4.Fink AS, Campbell DA, Jr, Mentzer RM, Jr, et al. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-veterans administration hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Ann Surg 2002;236:344–53 discussion 353–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleetcroft R, Steel N, Cookson R, et al. Incentive payments are not related to expected health gain in the pay for performance scheme for UK primary care: cross-sectional analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall SE, Holman CD, Finn J, et al. Improving the evidence base for promoting quality and equity of surgical care using population-based linkage of administrative health records. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:415–20 Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanley JA, Dendukuri N. Efficient sampling approaches to address confounding in database studies. Stat Methods Med Res 2009;18:81–105 Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneeweiss S. Developments in post-marketing comparative effectiveness research. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;82:143–56 Review [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan JP, Diggs BS, Sheppard BC, et al. The national mortality burden and significant factors associated with open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy: 1997–2006. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fusco D, Barone AP, Sorge C, et al. P.Re.Val.E.: outcome research program for the evaluation of health care quality in Lazio, Italy. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinnarelli L, Nuti S, Sorge C, et al. What drives hospital performance? The impact of comparative outcome evaluation of patients admitted for hip fracture in two Italian regions. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:127–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keulemans YC, Venneman NG, Gouma DJ, et al. New strategies for the treatment of gallstone disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 2002;236:87–90 Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology—guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut 2008;57:1004–21 Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varela JE, Wilson SE, Nguyen NT. Laparoscopic surgery significantly reduces surgical-site infections compared with open surgery. Surg Endosc 2010;24:270–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen NT, Hinojosa MW, Fayad C, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is associated with a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism compared with open surgery. Ann Surg 2007;246:1021–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolan JP, Diggs BS, Sheppard BC, et al. Ten-year trend in the national volume of bile duct injuries requiring operative repair. Surg Endosc 2005;19:967–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, et al. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2003;290:2168–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giger U, Ouaissi M, Schmitz SF, et al. Bile duct injury and use of cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2011;98:391–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballal M, David G, Willmott S, et al. Conversion after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in England. Surg Endosc 2009;23:2338–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armitage JN, van der Meulen JH. Royal College of Surgeons Co-morbidity Consensus Group Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the royal college of surgeons charlson score. Br J Surg 2010;97:772–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yetkin G, Uludag M, Oba S, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients. JSLS 2009;13:587–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russ AJ, Obma KL, Rajamanickam V, et al. Laparoscopy improves short-term outcomes after surgery for diverticular disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2267–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pessaux P, Tuech JJ, Derouet N, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly: a prospective study. Surg Endosc 2000;14:1067–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaafarani HM, Rosen AK. Using administrative data to identify surgical adverse events: an introduction to the Patient Safety Indicators. Am J Surg 2009;198(5 Suppl):S63–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jhung MA, Banerjee SN. Administrative coding data and health care-associated infections. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:949–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcà M, Fusco D, Barone AP, et al. Risk adjustment and outcome research. Part I. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2006;7:682–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Agostino RB. Tutorials in biostatistics. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Statist Med 1998;17:2265–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey Goldstein Multilevel statistical models. 3rd edn New York: Oxford University Press Inc, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HO, Yun JW, Shin JH, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not influenced by chronological age in the elderly. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:722–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman KJ, Lash TL, Grrenland S. Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn, Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glance LG, Dick AW, Osler TM, et al. Accuracy of hospital report cards based on administrative data. Health Serv Res 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1413–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shamiyeh A, Danis J, Wayand W, et al. 14-year analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: conversion—when and why? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2007;17:271–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keus F, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Open, small-incision, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. An overview of Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD008318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romy S, Eisenring MC, Bettschart V, et al. Laparoscope use and surgical site infections in digestive surgery. Ann Surg 2008;247:627–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.