Abstract

Sensory neurons in vertebrates are derived from two embryonic transient cell sources: neural crest (NC) and ectodermal placodes. The placodes are thickenings of ectodermal tissue that are responsible for the formation of cranial ganglia as well as complex sensory organs that include the lens, inner ear, and olfactory epithelium. The NC cells have been indicated to arise at the edges of the neural plate/dorsal neural tube, from both the neural plate and the epidermis in response to reciprocal interactions Moury and Jacobson (Dev Biol 141:243–253, 1990). NC cells migrate throughout the organism and give rise to a multitude of cell types that include melanocytes, cartilage and connective tissue of the head, components of the cranial nerves, the dorsal root ganglia, and Schwann cells. The embryonic definition of these two transient populations and their relative contribution to the formation of sensory organs has been investigated and debated for several decades (Basch and Bronner-Fraser, Adv Exp Med Biol 589:24–31, 2006; Basch et al., Nature 441:218–222, 2006) review (Baker and Bronner-Fraser, Dev Biol 232:1–61, 2001). Historically, all placodes have been described as exclusively derived from non-neural ectodermal progenitors. Recent genetic fate-mapping studies suggested a NC contribution to the olfactory placodes (OP) as well as the otic (auditory) placodes in rodents (Murdoch and Roskams, J NeurosciOff J Soc Neurosci 28:4271–4282, 2008; Murdoch et al., J Neurosci 30:9523–9532, 2010; Forni et al., J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 31:6915–6927, 2011b; Freyer et al., Development 138:5403–5414, 2011; Katoh et al., Mol Brain 4:34, 2011). This review analyzes and discusses some recent developmental studies on the OP, placodal derivatives, and olfactory system.

Keywords: Olfactory placode, Neural crest, Olfactory ensheathing cells, Migratory mass, GnRH-1 neurons

From the Olfactory Placode to the Migratory Mass

Placodes are focal areas of specialized tissue that undergo morphological changes, such as thickening and invagination, in response to environmental and intrinsic stimuli (Fig. 1). It has been proposed that all placodes are derived from the induction of a contiguous pre-placodal field of cells located around the anterior neural plate [1–3]. With respect to the olfactory placodes (OP), graft experiments in chicken and quail have shown that the OP does arise from cells along the anterior neural folds ([4] reviewed in [5]). However, fate-mapping studies in zebrafish and chicken that focused on pre-placodal stages, suggested that both olfactory and otic placodes arise from the recruitment of a large field of intermingled heterogeneous cells, including neural crest (NC) cells, that converge to form placodes in response to inductive signals [6, 7]. Evidence in mouse also indicates that these two cranial placodes are composed of cells of heterogeneous genetic lineages [8, 9]. In the OP of rodents, cells sharing common genetic lineage with the NC have been shown to differentiate into subsets of sensory neurons, support cells, cell of the respiratory epithelium, peptidergic neurons, and olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs; specialized glia of the olfactory system) [8–11]. However, graft based studies in chicken [12, 13] suggest that although NC cells are responsible for the formation of the OECs, sensory neurons and peptidergic neurons solely derive from non-neural ectodermal progenitors of the anterior neural folds [12, 13]. So, are we any closer to understanding the cell lineage of the progenitors of sensory placodes?

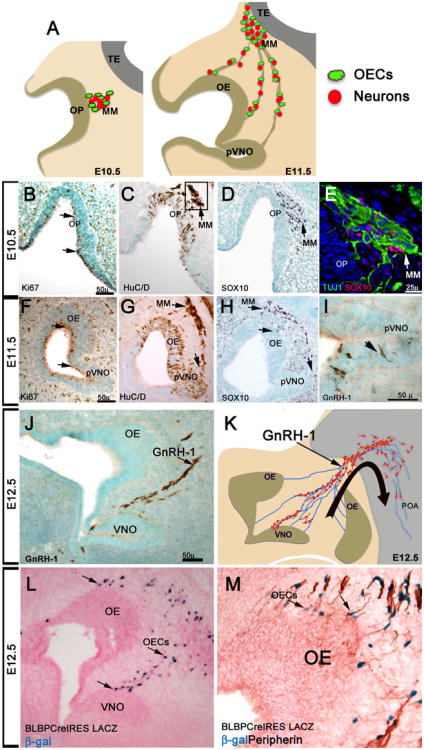

Fig. 1.

Olfactory placode, olfactory pit and migratory mass. a Schematic showing olfactory placode (OP) and migratory mass (MM) at E10.5 and olfactory epithelium (OE), putative vomeronasal organ (pVNO), and MM and telencephalon at E11.5. b–e E10.5. f–i E11.5. b, f Ki67 immunostaining highlights proliferative progenitors in the OP and olfactory pit (brown, arrows). c, g HuC/D immunostaining labels neuronal precursors in the OP and MM at E10.5 (c arrow; boxed) and neurons in the OE, pVNO and along the MM at E11.5 (g, arrows). d, h Sox10 labels the glial component of the MM at E10.5, and glia distributed along the migratory path at E11.5, compare (g)–(h). e Tuj1/Sox10 double immunostaining for neurons (green) and glia (red) in the MM (area corresponds to box in (c) shows no co-expression. i Early GnRH-1 expressing neurons proximal to the putative VNO. j Immunolabeled GnRH-1 neurons migrating, as part of the MM, from the developing VNO to the forebrain. k Schematic illustrating the migration of GnRH neurons from the olfactory area to the preoptic area (POA) of the brain. l X-gal reaction on E12.5 section of BLBP CreIRES LacZ. OECs cells (blue) positive for BLBP expression distributed along the migratory path starting from the developing OE and VNO (arrows). m Peripherin staining and X-gal reaction on section of BLBP Cre IRES LACZ reveals OECs (arrows) associated with olfactory fibers starting from the OE

The OP in mouse is detectable around 9.5 days of development (E9.5) and neuronal differentiation in the OP starts between E10 and 10.5 [14]. Shortly after placodal invagination, numerous cells delaminate [15] and migrate out of the placode to the nasal mesenchyme as neuronal projections start to extend from the invaginating placode to the developing telencephalon [16–18] (Fig. 1). The existence of cells migrating out of the nasal placode has been described over a century ago [16]. Later analysis in multiple species showed that the olfactory pit is a source of heterogeneous migratory cells, including neurons, glia, and proliferative progenitor cells [17, 19–27]. The migratory cells, together with the nascent axons, form the migratory mass (MM) [28]. The identity and destiny of only a subset of the postmitotic neuronal precursors [22, 29, 30] in the MM is known (Fig. 1a–k). These include peptidergic neurons expressing either neuropeptide-Y [31] or gonadotropic releasing hormone-1 (GnRH-1) [17, 27], with the latter forming the GnRH-1 neuroendocrine system that is essential for reproduction (review, [32]) (Fig. 1j, k). Olfactory ensheathing cells are associated with the nascent olfactory fibers and neurons of the MM and migrate toward the part of the developing forebrain that will later form the olfactory bulb [19, 22] (Fig. 1d, e, and h). The OECs can be genetically traced [33, 34] and visualized using mouse models expressing Cre recombinase and or reporter genes under the control of promoters such as Sox10 or BLBP (Fig. 1l, m) [33, 35]. It has been suggested that cells of the MM play a role in perforation of the basal lamina of the OP [22], guiding neuronal projections from the placode to the forebrain, and influencing the induction and development of the olfactory bulb [19, 36–39]. However, the developmental role of the different cells of the MM and their final destination once they have completed development is still only partially understood.

Between E10.5 and E11.5 in mouse, when the placode progressively invaginates forming the olfactory pit and MM, the composition of the pre-olfactory epithelium (OE) and surrounding mesenchyme is dramatically different from what is observed in the developed olfactory mucosa. At early stages, there is no lamina propria and mucus-producing (Bowman's) glands [14], differentiated sustentacular/support cells, and mitotic basal progenitors are absent [40] (see Fig. 2e for a schematic representation). In the invaginating OP, as described in other placodes, the mitotic progenitors are localized at the apical portion of the pit facing the lumen of the developing olfactory cavity [14, 15, 40–42]. Progenitor cells in the invaginating OP respond to environmental cues and are distinguishable based on their expression of molecular markers and proliferative ability [43]. BrdU birth date tracing experiments in mouse, as well as neurogenic marker tracing in chicken, have shown that a large portion of the postmitotic neuronal cells born in the first neurogenic divisions (E9.5 and E10.5 in mouse) are destined to become part of the MM rather than the OE [42, 44]. This suggests that the molecular cues at early phases of placodal development are distinct from those responsible for the formation of the olfactory sensory epithelium at later embryonic and postnatal stages.

Fig. 2.

Structure and cell composition of olfactory mucosa. E19.5 (a– d) OMP immunostaining (a) labels soma of olfactory sensory neurons in olfactory epithelium (OE) and olfactory axons in lamina propria (LP). b p75 immunostaining labels cells and connective tissue of the LP. c BLBP immunostaining labels olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) in LP and at the basal portion of the OE. d Merged image of (b) and (c) showing OECs in LP. e Schematic of the cell composition of the olfactory mucosa. f Ki67/YFP double immunostaining on sections from BLBPCre/RosaYFP mouse highlights OECs in LP and proliferative OECs proximal to the proliferative basal progenitor cells of the OE. g Hu/YFP double immunostaining on BLBPCre/RosaYFP section shows OECs at the basal portion of the OE extend their cytoplasm around Hu+ olfactory neurons. h Olfactory ensheathing cells surrounding peripherin-positive olfactory axons bundles

Kallmann Syndrome, GnRH-1 Neurons, and GnRH-1 Cell Lineage

GnRH-1 neurons, a component of the MM, originate in the nasal area and migrate along axonal projections to the forebrain (Fig. 1j–k). These cells play a central role in controlling sexual development and reproduction via the hypothalamicpituitary-gonadal axis [17, 27, 45]. The embryonic origin of GnRH-1 neurons has been a matter of debate for several decades. Studies on different animal models have provided compelling and contrasting evidence of placodal, nonplacodal ectodermal, and NC origins for these cells [8, 13, 27, 46–50] and thus are an important component in the debate on the origin and composition of the OP itself.

Morphological studies in mouse indicate GnRH-1 neurons originate from slow dividing progenitor cells in the Ap2a and Meis 1 expressing area at the border between the putative respiratory epithelium and developing vomeronasal organ [27, 42, 43, 51]. Postmitotic GnRH-1 precursors, in mouse, start to express the GnRH-1 peptide around E11.5 as they delaminate and migrate, along axonal projections, to the forebrain [27, 32, 42, 46, 52, 53]. Though morphological evidence points to the existence of GnRH-1 progenitors in the olfactory pit, it does not clearly define the embryonic lineage for these cells [7, 42, 50, 54]. Using genetic lineage tracing in mouse, it was confirmed that the majority, but not all, of GnRH-1 neurons originate from placodal ectodermal progenitors [8]. By contrast, recent cell fate tracing in chicken, based on surgical grafts of putative neural fold ectoderm versus NC, suggested exclusive placodal ectodermal origin for GnRH-1 neurons and no NC contribution to the OP in chicken [13]. However, in a variety of species (including chick), progenitor cells of putative NC origin have been identified within the OP [8–10, 50] and together with genetic lineage tracing in mice, indicate an additional NC contribution to the GnRH-1 population can occur [8].

Kallmann syndrome (KS) is a pathology associated with defects in development of the olfactory system and impaired migration of GnRH-1 neurons [55]. The clinical features of KS include total or partial anosmia (lack of smell) and lack of pubertal onset [32, 56, 57]. Though anosmia, which is usually associated with aplasia or hypoplasia of olfactory bulbs and tracts, and hypogonadism are the classic clinical features of KS, additional NC-associated defects have been reported, including craniofacial defects, cleft palate and lip, sensorineural defects, deafness, cerebellar ataxia, dental agenesys, abnormal kidney morphogenesis, heart defects, and coloboma [58–65]. The NC-associated defects in this syndrome are consistent with NC-derived cells contributing to both the GnRH-1 neuronal system as well as the developing olfactory system.

Thus far, only a few genes have been identified that play a role in controlling olfactory/GnRH-1 development and correlate with the etiology of KS in humans [47]. These include mutations affecting Kal1 (Anosmin), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8), prokineticin 2 and its receptor (PROK2/PROKR2), chromodomainhelicase-DNA-binding 7 (CHD7) [66, 67], and nasal embryonic LHRH factor [68] genes, which have been associated with the etiology of ∼35% Kallmann cases [69].

Animal models indicate that genes involved in FGF8 signaling, such as Kal1, FGFR1, FGF8, and CHD7, are crucial for both placodal development and cell specification, as well as for NC formation, migration, and survival [70–75]. Due to the broad effects of the mutations identified thus far and the intimate relation between NC-derived nasal mesenchyme and olfactory placode development [76, 77], no clear picture emerges about cell autonomous effects and the hierarchy of molecular and cellular events underlying normal olfactory/GnRH-1 development.

The Olfactory Mucosa and the Stem Cell Puzzle

The mature olfactory system has a peripheral component, the olfactory mucosa, and a central component, the olfactory bulbs, which process and redirect peripheral inputs to the brain cortex (Fig. 2). The olfactory mucosa (Fig. 2) comprised the OE, which is the superficial layer, and the lamina propria, a layer of vascularized, NC-derived ectomesenchymal tissue juxtaposed to the OE. The OE is a pseudo-stratified epithelium composed of olfactory sensory neurons, sustentacular cells, olfactory progenitor cells, and Bowman's gland ducts. The acinus of the mucus-producing Bowman's glands and the OECs are located within the lamina propria (Fig. 2). Olfactory neurons project their axons from the OE to the brain, going across the lamina propria, connective tissue, and bones. Olfactory ensheathing cells wrap olfactory axons in bundles from the basal lamina of the OE to the olfactory bulb. The OE is in direct contact with the external environment and therefore exposed to a multitude of chemical and biological insults. Luckily, the OE retains a unique regenerative ability throughout life. As such, it is able to regenerate aged or damaged neurons as well as the full repertoire of non-neuronal cells, ensuring functional recovery and chemo-detection [78, 79]. Numerous lines of evidence support the existence of distinct kinds of olfactory progenitors and stem cells in both the OE and lamina propria, which differ in molecular expression profiles, hierarchical lineage relationship, and the ability to differentiate into different cell types (potency). Do these studies help define the make-up of the OP?

Within the OE, two olfactory basal progenitor/stem cell types have been described: globose basal cells (GBCs) and horizontal basal cells (HBCs) [80–82]. Intrinsic cell features, such as receptors, transcriptional factors, and epigenetic factors are determinants in defining the potency of progenitor cells [43, 83]. GBCs and HBCs differ in terms of molecular expression. GBCs express Sox2, Pax6, and GB2 (globose cell marker) and, depending on their differentiation state, can also express ASCL-1/MASH1 (as transit amplifier progenitors) and tubulinIII [84]. HBCs also express Pax6 and Sox2 [85] and express TrKa, p75, NT4, cyto-keratin, EGFR, ICAM-1 (CD54), β1-integrin, and β4-integrin. In addition, α1- (CD49a), α3- (CD49c), and α6-integrins (CD49f) may be differentially expressed among HBCs [84, 86, 87]. Sustentacular cells, also express Pax6 and Sox2 [85] and are able to self-replicate, a potential stem role for this cells is still an open question [34].

HBCs have been described as having a high level of potency (multipotency). In fact, in vivo experiments based on genetic lineage tracing identified populations of HBCs able to regenerate the full repertoire of OE cells after lesion [88] and in vitro observations on clonally selected populations of HBCs proved that these cells can produce OECs in addition to epithelial cells [84]. While studies have identified both the cell types in, and the regenerative ability of olfactory progenitors in postnatal OE, there still is little known about the relationship between early embryonic olfactory progenitors, gene expression, and lineage of the olfactory progenitor/stem cells in postnatal/adult stages [34, 40, 43, 89–91]. Whether HBCs are a homogenous population or composed of multiple cell types is not fully understood, as there is yet no identified unique molecular expression pattern. The embryonic lineage of these cells is also still a matter of investigation [34, 84].

Studies seeking to isolate stem cells from olfactory mucosa for broad regenerative purposes have identified additional multipotent “stem” cells in the lamina propria of mouse, rat and human. These cells are able to generate a wide range of cell types such as bone, adipose, smooth muscle cells, glia and neurons [92–96]. The phenotypic potency of these cells to produce both neuronal and mesodermal cells is similar to that described for skin-derived precursors, which are believed to be of NC origin [97]. It has to be noted that ecto-mesenchymal derivatives of the head (cartilage, bone, and connective tissue), including those of the lamina propria, are in large part derived from the NC and NC subfields [76, 98–100]. Therefore, it is likely that multipotent NC- derived progenitors within the lamina propria of mammals retain the ability to acquire specific phenotypes, including olfactory cell lineages, in response to specific developmental or regenerative cues, and might function as additional stem cell reserves for the olfactory mucosa [10, 97, 101, 102]. This interpretation is consistent with the fact that several genetic lineage tracing studies using Cre-drivers able to recombine in NC (P0, Wnt1, and PAx7), have identified putative NC cells in the embryonic and adult OE and lamina propria [8–11].

NC Origin of OECs and Contribution to the OP; Convergence and Contradictions

The OECs are a specialized glial population of the postnatal olfactory system (Fig. 3). Mature OECs localize together with committed progenitors within the lamina propria and along the olfactory fibers projecting to the bulbs. When transplanted into lesioned spinal cord, OECs have the ability to myelinate axons like Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system [37, 103, 104]. Like Schwann cells [105], OEC precursors express Sox10 and BLBP (brain lipid binding protein or fatty acid-binding protein 7) [22, 34, 42] and OECs can express the astrocyte “specific” marker (GFAP), the low-affinity p75 nerve growth factor receptor (p75 NGFr), S100, Erbb2, as well as adhesion molecules such as laminin and N-CAM. In rodents, the expression of the OEC markers GFAP, p75, and S100 has been reported in putative OEC precursors within the OE and along the axonal projection at later developmental stages [87, 106]. Based on heterogeneity in molecular expression and regenerative ability when transplanted in lesioned spinal cord, the existence of different OEC subpopulations have been hypothesized [107–111].

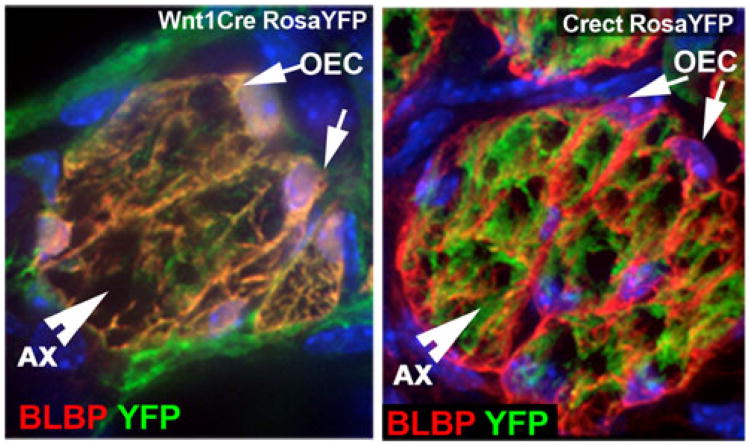

Fig. 3.

Neural crest origin of the OECs, genetic lineage tracing. BLBP immunostaining (red) of OECs on sections from a Wnt1Cre/RosaYFP mouse (left) and Crect/RosaYFP mouse (right) highlights that OECs are positive for Wnt1Cre tracing and negative for Crect tracing (ectodermal) while most axons in the bundle are negative for Wnt1Cre tracing but positive for the ectodermal tracing

The similarity between OECs and Schwann cells (reviewed by Barnett [112]), in molecular marker expression, morphology, and cell behavior has puzzled the scientific community for decades [113–115] and suggested a potential common origin for these cell types [112, 116–120]. Traditional morphological studies, together with studies based on temporal gene/protein marker expression, had been unable to unravel the lineage and ontogeny of OECs. The OECs were initially believed to be peripheral Schwann cells [121] originating from NC precursors that migrated from the developing dorsal neural tube to the lamina propria, but a potential local origin from the placode was not excluded [122]. For the next two and half decades, evidence for a placodal origin of OECs increased, though NC was never totally excluded. These studies included:

Observations at early developmental stages of placodal invagination, when the lamina propria was not yet formed, [123],

Electron microscopy indicating OECs originated from olfactory basal cell progenitors [124],

Quail/chicken grafts of the pre-placodal anterior neural folds [4] and,

Isolation of multipotent stem cells from the OE of mouse with the ability to generate, OMP-, Golf-, adenylate cyclase III-positive olfactory neurons, and cells positive for OEC markers GFAP, S100, and p75 [84, 125, 126].

However, recent reports have provided compelling evidence of a NC origin for these cells [8, 10–12, 127]. Lineage tracing in mouse, based on Pax7 expression [11], an early NC marker that is also expressed by a subset of cells in the anterior neural folds [128], first indicated distinct progenitor cells in the OP. Cells positive for Pax7 lineage were shown to give rise to a discrete population of neuronal and non-neuronal cells within the OE, subsets of neuronal cells of the MM and to the entire population of OECs [11]. These data suggested a potential NC contribution to the OP and NC origin for the OECs. A NC origin for OECs was demonstrated by anterior neural fold ectoderm grafts and by NC grafts in avian animal models [12]. In addition, two other studies in mouse, one using Wnt1Cre genetic lineage [12] and the other tracing placodal ectoderm and NC derivatives using a Cre ectodermal (Crect) mouse line as a superficial ectodermal tracer and Wnt1Cre mouse line as NC tracer [8], converged in defining the origin of OECs from NC- and not from ectodermal- progenitors.

Though these studies agreed about the NC origin of the OECs, some controversies arose. Barraud and coworkers showed, in avian models, that the OECs did not originate from grafted anterior neural fold ectoderm, which gives rise to the OP, but rather by grafted NC that also contributed to the formation of the nasal mesenchyme. Cells originating from the grafted NC were not detected in the placode. This suggested that OECs originate exclusively from NC progenitors that do not belong to the OE [12]. The graft experiments showed that the grafted NC were able to give rise to some of the p75-positive cells in the lamina propria and to P0-positive cells around the bulb. Notably, occasional OECs from anterior neural fold grafts (presumptive ectoderm) have also been described, but these cells are believed to derive from NC contamination of the grafted tissue [12]. These data suggested that the OECs originate from progenitor NC cells that (a) follow unknown routes to invade developing olfactory fibers as previously hypothesized [121] or (b) originate from differentiation of the nasal mesenchyme.

Lineage tracing in mouse [8] also demonstrated, that in mammals as in avian, the OECs were negative for ectodermal tracing (Crect) but positive for NC lineage (Wnt1Cre). In contrast to results described in chick, Forni et al. [8] suggested that multipotent cells of putative NC origin integrated in the OP, giving rise to OECs and contributing to the placodal-derived cell repertoire. This was based on the presence of progenitors positive for Wnt1 tracing in the OP, which was not observed by Barraud et al. [12], but confirmed by others [9, 10], and by complementary chimeric ectodermal (Crect) recombination in the OE and in placodal derivatives [8].

A potentially similar example of contrasting results in cell fate tracing obtained using similar paradigms (tissue grafts VS genetic tracing) has emerged in studies on the otic placode. Quail/chicken otic placode grafts indicated placodal origin for the inner ear though high levels of host/donor chimerism was observed in the inner ear after graft [129]. Yet, a recent genetic lineage tracing in mouse indicated that such chimerism might derive by the ability of NC cells to integrate in the developing otic placode and to contribute to the formation of the inner ear. These studies revealed a dual NC/ectodermal origin for this organ [9], as previously suggested for the neuromasts of the lateral line in fish [130]. So the question remains, for both the otic and olfactory placodes: are the interpretations biased by the technique?

Different Strategies and Different Outcomes

In graft experiments, portions of tissues of presumptive uniform cellular composition and cellular identity are topographically identified (relying on genetic expression maps at given developmental stages), mechanically excised and grafted into a host animal that has been deprived of the corresponding tissue. Though this technology has provided crucial information on topographic lineage of multiple tissues [4], it is not without problems. In fact, it does not allow one to establish if clonal cell heterogeneity existed prior to grafting the chosen tissue [7, 128]. In addition, the substitution of the host tissue with the donor grafted tissue is often incomplete and consequently does not always permit a clear-cut discrimination between cell contamination from remaining host tissue and contributions of cells of other lineages [9, 12, 129]. Tissue graft tracing are intrinsically biased by a priori defining a temporal and topographic boarder and a clonal cell identity based on visual detectability of gene expression and previous fate maps.

Genetic lineage tracing relies on the identification of clonal contribution of progenitors with specific genetic features rather than on topographic localization, a key feature for tracing migratory/invasive cells such as the NC. Broadly described downsides of genetic lineage tracing are:

Potential ectopic [131] transgene expression,

Differences in the timing of transgene/endogenous gene expression, and

Partial penetrance and/or variability of recombination depending on the genetic mouse background [132].

So, one sees that both of these essential “lineage tracing” tools have caveats. However, are both interpretations of NC contributions to the OP possible?

Grafts and genetic lineage data may not necessary be mutually exclusive. The model of olfactory system development after grafts in avian [12], negates the existence of OEC progenitors within the OE [106] and implies that the previously identified olfactory multipotent progenitors isolated from OE [84, 124–126] might result from NC contamination. Support for differentiation of NC nasal mesenchyme to OEC cells, is the fact that mesenchymal cells are able to acquire a Schwann-like phenotype in response to unknown axonal inductive factors [133]. It is also possible that the p75- and P0-positive cells derived by NC grafts identified by Barraud and coworkers [12] could be derived from afferents of the peripheral nervous system. In fact, a contribution to the OEC population, could come from the ethmoid and nasopalatine branches of the trigeminal nerve, as trigeminal afferents to both OE, lamina propria and olfactory bulb have been described in multiple species [134–138].

On the other side, in support for the model proposed by Forni et al. [8] there is the following evidence. First, at E10.5 in mouse, OEC progenitors positive for Sox10 and Wnt1 Cre tracing appeared in a continuum, streaming out of the developing placode in association with the neurons of the MM [8]. Second, few olfactory axons, if any, are detectable at this early stage [22] making a connection between OE and the developing trigeminal nerve unlikely. Third, in vitro recombination experiments in mouse explants [77, 139] showed no mixing of frontonasal mesenchymal cells and presumptive placodal cells in the pit nor in the N-CAM expressing cells (neuronal precursors and OECs) of the migratory mass. Moreover, other independent NC genetic lineage tracing experiments in rodents based on the use of Wnt1cre line as well as other Cre animal models able to recombine in NC, such as Pax7Cre, P0Cre, and Pax3Cre, have confirmed recombination in the OECs as well as in progenitors within the OP and later on in the OE [9–11]. The convergence of these genetic tracing studies, together with the chimerism for ectodermal (Crect) tracing, make it unlikely that these observations are the result of recombination artifacts as suggested by others [13]. So how can one reconcile these different findings?

Possible interpretations that could reconcile the discrepancy between physical tissue grafts [12, 13] and NC genetic lineage experiments [8, 10, 11, 128] are:

At least part of the cells localized within the anterior neural folds, which are accepted as progenitors of the OP, share the same developmental potential of neural crest [140]; however, these cells do not usually undergo epithelial to mesenchymal transitions. The anterior neural folds, in which the expression of NC markers Snail1/2 is prevented by inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling via Dkk1 [140], might be able to generate early subsets of progenitor cells that share common Pax7, Wnt1, P0, PAX3 genetic lineage and potency with the “classic” NC cells originating along the dorsal neural folds [141–144],

Stem cells able to give rise to OECs have been described and isolated from both OE and lamina propria [84, 125, 126, 145], if not simply resulting from mutual tissue contamination, would support the existence of NC progenitors in both regions, and

The results obtained by grafts in chicken and by genetic lineage tracing in mouse, if not species specific, represent two independent NC contributions to the olfactory system. Thus, it is possible that genetic tracing visualized an early developmental event in which a small NC population integrated into the developing pre-placodal tissues, contributing to the formation of placodal-derived neurons, and a second NC contribution, detected by graft experiments, gives rise to the nasal mesenchyme and glial cells in the olfactory system.

Conclusions

Sensory placodes and NC share a number of similarities: they both originate from specialized cells of ectodermal origin at the border of the neural plate. Both placodes and NC are able to generate cells with a plethora of different identities including sensory neurons and secretory cells. A potential common evolution for NC and placodes has been proposed [6, 146]. Based on evidence, proving the ability of the OP to give rise to glial cells and sensory neurons, the OP has for long time been believed to be the only placode able to produce Schwann-like ensheathing glia [4, 124], a concept that found its constrain in the dogmatic vision of its exclusive ectodermal composition [7]. Based on this assumption, an overlapping developmental potential for placode and NC, to produce sensory neurons and glia, has been accepted until recent times.

The identification of a NC origin for the OECs indicates that all ensheathing glial cells of the peripheral system of the head, cranial ganglia, olfactory, and auditory system, are of NC origin. The established NC origin of the OECs and the identification of pluripotent NC-derived progenitors within the placodally derived structures [84] is an important point when considering the evolution of NC and placodal structures and more broadly the cellular and molecular readout of syndromic pathologies such as CHARGE and specific clinical cases of KS [71, 147].

The interaction between NC-derived cells and placodal-derived structures is intimate and crucial at multiple developmental levels. Neural crest-derived glial cells arising from the hindbrain are essential for the migration of epibranchial placode-derived neurons, and for the axonal targeting to the hindbrain [148]. The interaction between placodal and NC-derived components of the trigeminal ganglion is critical for both ganglion development and routing [149]. Various data indicate a key role for OECs in olfactory development, but thus far no specific animal models have been analyzed in this regard. OEC-specific ablation experiments in vivo and identification of genes responsible for OEC development are needed to unravel whether OEC development may underlie specific pathologies affecting olfactory and/or GnRH development.

The existence of progenitor cells in the OE with the ability to give rise to cells with different destinies, has been known for over a decade. Recent isolation and in vitro expansion of progenitors positive for NC tracing suggested these might be part of the previously identified multipotent progenitors [10, 84, 94, 150, 151]. Understanding the NC contribution to the olfactory system [7, 8, 50], is essential for re-interpretation of studies based on the use of olfactory-derived cells for regenerative purposes in the peripheral nervous system [111, 152–154]. Neural crest derivatives such as mesenchymal cells, Schwann cells, skin-derived NC progenitors and peripheral nervous system progenitors retain an extraordinary level of phenotypic plasticity in response of environmental cues [155–161]. The new findings suggesting that NC-derived cells can integrate in the developing sensory placodes and give rise to overlapping cell types as those of ectodermal origin [8–10] are exciting. This possibility provides a new scenario for understanding the biology and potency of NC cells and the role played by environmental milieus [155] in cell fate determination of cells deriving from progenitors of different embryonic origin.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. David H. Gutmann (Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA) for sharing the BLBPCreIRESLacZ mouse line.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya S, Bailey AP, Bronner-Fraser M, Streit A. Segregation of lens and olfactory precursors from a common territory: cell sorting and reciprocity of Dlx5 and Pax6 expression. Dev Biol. 2004;271:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozlowski DJ, Murakami T, Ho RK, Weinberg ES. Regional cell movement and tissue patterning in the zebrafish embryo revealed by fate mapping with caged fluorescein. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:551–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verwoerd CD, van Oostrom CG. Cephalic neural crest and placodes. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1979;58:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couly GF, Le Douarin NM. Mapping of the early neural primordium in quail-chick chimeras. I. Developmental relationships between placodes, facial ectoderm, and prosencephalon. Dev Biol. 1985;110:422–439. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlosser G. Do vertebrate neural crest and cranial placodes have a common evolutionary origin? Bioessays. 2008;30:659–672. doi: 10.1002/bies.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streit A. Extensive cell movements accompany formation of the otic placode. Dev Biol. 2002;249:237–254. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitlock KE, Westerfield M. The olfactory placodes of the zebrafish form by convergence of cellular fields at the edge of the neural plate. Development. 2000;127:3645–3653. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forni PE, Taylor-Burds C, Melvin VS, Williams T, Wray S. Neural crest and ectodermal cells intermix in the nasal placode to give rise to GnRH-1 neurons, sensory neurons, and olfactory ensheathing cells. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:6915–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6087-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freyer L, Aggarwal V, Morrow BE. Dual embryonic origin of the mammalian otic vesicle forming the inner ear. Development. 2011;138:5403–5414. doi: 10.1242/dev.069849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katoh H, Shibata S, Fukuda K, Sato M, Satoh E, Nagoshi N, Minematsu T, Matsuzaki Y, Akazawa C, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. The dual origin of the peripheral olfactory system: placode and neural crest. Mol Brain. 2011;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murdoch B, DelConte C, Garcia-Castro MI. Embryonic Pax7-expressing progenitors contribute multiple cell types to the postnatal olfactory epithelium. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9523–9532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0867-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barraud P, Seferiadis AA, Tyson LD, Zwart MF, Szabo-Rogers HL, Ruhrberg C, Liu KJ, Baker CV. Neural crest origin of olfactory ensheathing glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21040–21045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012248107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabado V, Barraud P, Baker CV, Streit A. Specification of GnRH-1 neurons by antagonistic FGF and retinoic acid signaling. Dev Biol. 2011;362:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuschieri A, Bannister LH. The development of the olfactory mucosa in the mouse: light microscopy. J Anat. 1975;119:277–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham A, Blentic A, Duque S, Begbie J. Delamination of cells from neurogenic placodes does not involve an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Development. 2007;134:4141–4145. doi: 10.1242/dev.02886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedford EA. The early history of the olfactory nerve in swine. J Comp Neurol. 1904;14:390–410. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature. 1989;338:161–164. doi: 10.1038/338161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wray S, Key S, Qualls R, Fueshko SM. A subset of peripherin positive olfactory axons delineates the luteinizing hormone releasing hormone neuronal migratory pathway in developing mouse. Dev Biol. 1994;166:349–354. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doucette R. Glial influences on axonal growth in the primary olfactory system. Glia. 1990;3:433–449. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fornaro M, Geuna S. Confocal imaging of HuC/D RNA-binding proteins in adult rat primary sensory neurons. Ann Anat. 2001;183:471–473. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(01)80206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fornaro M, Geuna S, Fasolo A, Giacobini-Robecchi MG. HuC/D confocal imaging points to olfactory migratory cells as the first cell population that expresses a post-mitotic neuronal phenotype in the chick embryo. Neuroscience. 2003;122:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller AM, Treloar HB, Greer CA. Composition of the migratory mass during development of the olfactory nerve. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4825–4841. doi: 10.1002/cne.22497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarting GA, Gridley T, Henion TR. Notch1 expression and ligand interactions in progenitor cells of the mouse olfactory epithelium. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:543–553. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarozzo G, Peretto P, Fasolo A. Cell migration from the olfactory placode and the ontogeny of the neuroendocrine compartments. Zoolog Sci. 1995;12:367–383. doi: 10.2108/zsj.12.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valverde F, Heredia M, Santacana M. Characterization of neuronal cell varieties migrating from the olfactory epithelium during prenatal development in the rat. Immunocytochemical study using antibodies against olfactory marker protein (OMP) and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;71:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitlock KE, Westerfield M. A transient population of neurons pioneers the olfactory pathway in the zebrafish. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8919–8927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08919.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wray S, Grant P, Gainer H. Evidence that cells expressing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone mRNA in the mouse are derived from progenitor cells in the olfactory placode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8132–8136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farbman AI, Squinto LM. Early development of olfactory receptor cell axons. Brain Res. 1985;351:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conzelmann S, Levai O, Breer H, Strotmann J. Extraepithelial cells expressing distinct olfactory receptors are associated with axons of sensory cells with the same receptor type. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzenbacher K, Fleischer J, Breer H, Conzelmann S. Expression of olfactory receptors in the cribriform mesenchyme during prenatal development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilal EM, Chen JH, Silverman AJ. Joint migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons from olfactory placode to central nervous system. J Neurobiol. 1996;31:487–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199612)31:4<487::AID-NEU8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wray S. From nose to brain: development of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone-1 neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:743–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anthony TE, Mason HA, Gridley T, Fishell G, Heintz N. Brain lipid-binding protein is a direct target of Notch signaling in radial glial cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1028–1033. doi: 10.1101/gad.1302105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murdoch B, Roskams AJ. Olfactory epithelium progenitors: insights from transgenic mice and in vitro biology. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:581–599. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegedus B, Dasgupta B, Shin JE, Emnett RJ, Hart-Mahon EK, Elghazi L, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis-1 regulates neuronal and glial cell differentiation from neuroglial progenitors in vivo by both cAMP- and Rasdependent mechanisms. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:443–457. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graziadei PP, Monti-Graziadei AG. The influence of the olfactory placode on the development of the telencephalon in Xenopus laevis. Neuroscience. 1992;46:617–629. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90149-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramon-Cueto A, Avila J. Olfactory ensheathing glia: properties and function. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stout RP, Graziadei PP. Influence of the olfactory placode on the development of the brain in Xenopus laevis (Daudin). I. Axonal growth and connections of the transplanted olfactory placode. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2175–2186. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe Y, Inoue K, Okuyama-Yamamoto A, Nakai N, Nakatani J, Nibu K, Sato N, Iiboshi Y, Yusa K, Kondoh G, Takeda J, Terashima T, Takumi T. Fezf1 is required for penetration of the basal lamina by olfactory axons to promote olfactory development. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:565–584. doi: 10.1002/cne.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smart IH. Location and orientation of mitotic figures in the developing mouse olfactory epithelium. J Anat. 1971;109:243–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuschieri A, Bannister LH. The development of the olfactory mucosa in the mouse: electron microscopy. J Anat. 1975;119:471–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forni PE, Fornaro M, Guenette S, Wray S. A role for FE65 in controlling GnRH-1 neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2011;31:480–491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucker ES, Lehtinen MK, Maynard T, Zirlinger M, Dulac C, Rawson N, Pevny L, Lamantia AS. Proliferative and transcriptional identity of distinct classes of neural precursors in the mammalian olfactory epithelium. Development. 2010;137:2471–2481. doi: 10.1242/dev.049718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maier E, Gunhaga L. Dynamic expression of neurogenic markers in the developing chick olfactory epithelium. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1617–1625. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berghard A, Hagglund AC, Bohm S, Carlsson L. Lhx2-dependent specification of olfactory sensory neurons is required for successful integration of olfactory, vomeronasal, and GnRH neurons. Faseb J. 2012 doi: 10.1096/fj.12-206193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wray S, Nieburgs A, Elkabes S. Spatiotemporal cell expression of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in the prenatal mouse: evidence for an embryonic origin in the olfactory placode. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989;46:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wray S. Development of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:292–316. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3022(02)00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.el Amraoui A, Dubois PM. Experimental evidence for an early commitment of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons, with special regard to their origin from the ectoderm of nasal cavity presumptive territory. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:991–1002. doi: 10.1159/000126490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metz H, Wray S. Use of mutant mouse lines to investigate origin of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons: lineage independent of the adenohypophysis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:766–773. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitlock KE, Wolf CD, Boyce ML. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) cells arise from cranial neural crest and adenohypophyseal regions of the neural plate in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Dev Biol. 2003;257:140–152. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramer PR, Guerrero G, Krishnamurthy R, Mitchell PJ, Wray S. Ectopic expression of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and peripherin in the respiratory epithelium of mice lacking transcription factor AP-2alpha. Mech Dev. 2000;94:79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehm U, Zou Z, Buck LB. Feedback loops link odor and pheromone signaling with reproduction. Cell. 2005;123:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jasoni CL, Porteous RW, Herbison AE. Anatomical location of mature GnRH neurons corresponds with their birthdate in the developing mouse. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:524–531. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Onuma TA, Ding Y, Abraham E, Zohar Y, Ando H, Duan C. Regulation of temporal and spatial organization of newborn GnRH neurons by IGF signaling in zebrafish. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:11814–11824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6804-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kallmann FJBS. The genetic aspects of primary eunuchoidism. J Ment Defic. 1944;48:203–236. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan YM, Broder-Fingert S, Seminara SB. Reproductive functions of kisspeptin and Gpr54 across the life cycle of mice and men. Peptides. 2009;30:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trarbach EB, Teles MG, Costa EM, Abreu AP, Garmes HM, Guerra G, Jr, Baptista MT, de Castro M, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC. Screening of autosomal gene deletions in patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification: detection of a hemizygosis for the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albuisson J, Pecheux C, Carel JC, Lacombe D, Leheup B, Lapuzina P, Bouchard P, Legius E, Matthijs G, Wasniewska M, Delpech M, Young J, Hardelin JP, Dode C. Kallmann syndrome: 14 novel mutations in KAL1 and FGFR1 (KAL2) Hum Mutat. 2005;25:98–99. doi: 10.1002/humu.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bailleul-Forestier I, Gros C, Zenaty D, Bennaceur S, Leger J, de Roux N. Dental agenesis in Kallmann syndrome individuals with FGFR1 mutations. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaffe MJ, Currie J, Schwankhaus JD, Sherins RJ. Ophthalmic midline dysgenesis in Kallmann syndrome. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1987;8:171–174. doi: 10.3109/13816818709031464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ribeiro RS, Vieira TC, Abucham J. Reversible Kallmann syndrome: report of the first case with a KAL1 mutation and literature review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:285–290. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ueno H, Yamaguchi H, Katakami H, Matsukura S. A case of Kallmann syndrome associated with Dandy–Walker malformation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112:62–67. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Villanueva C, de Roux N. FGFR1 mutations in Kallmann syndrome. Front Horm Res. 2010;39:51–61. doi: 10.1159/000312693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zenaty D, Bretones P, Lambe C, Guemas I, David M, Leger J, de Roux N. Paediatric phenotype of Kallmann syndrome due to mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006:254–255. 78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, McMahon R, Charles SJ, Green JS, Moore AT, Barton DE, Yates JR. Genetic mapping of the Kallmann syndrome and X linked ocular albinism gene loci. J Med Genet. 1993;30:923–925. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.11.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bergman JE, Janssen N, Hoefsloot LH, Jongmans MC, Hofstra RM, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. CHD7 mutations and CHARGE syndrome: the clinical implications of an expanding phenotype. J Med Genet. 2011;48:334–342. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.087106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jongmans MC, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM, Pitteloud N, Ogata T, Sato N, Claahsen-van der Grinten HL, van der Donk K, Seminara S, Bergman JE, Brunner HG, Crowley WF, Jr, Hoefsloot LH. CHD7 mutations in patients initially diagnosed with Kallmann syndrome—the clinical overlap with CHARGE syndrome. Clin Genet. 2009;75:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trarbach EB, Baptista MT, Garmes HM, Hackel C. Molecular analysis of KAL-1, GnRH-R, NELF and EBF2 genes in a series of Kallmann syndrome and normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism patients. J Endocrinol. 2005;187:361–368. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bianco SD, Kaiser UB. The genetic and molecular basis of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:569–576. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abzhanov A, Tabin CJ. Shh and Fgf8 act synergistically to drive cartilage outgrowth during cranial development. Dev Biol. 2004;273:134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bajpai R, Chen DA, Rada-Iglesias A, Zhang J, Xiong Y, Helms J, Chang CP, Zhao Y, Swigut T, Wysocka J. CHD7 cooperates with PBAF to control multipotent neural crest formation. Nature. 2010;463:958–962. doi: 10.1038/nature08733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Creuzet S, Schuler B, Couly G, Le Douarin NM. Reciprocal relationships between Fgf8 and neural crest cells in facial and forebrain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4843–4847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400869101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Falardeau J, et al. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2822–2831. doi: 10.1172/JCI34538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kawauchi S, Shou J, Santos R, Hebert JM, McConnell SK, Mason I, Calof AL. Fgf8 expression defines a morphogenetic center required for olfactory neurogenesis and nasal cavity development in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:5211–5223. doi: 10.1242/dev.02143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trarbach EB, Abreu AP, Silveira LF, Garmes HM, Baptista MT, Teles MG, Costa EM, Mohammadi M, Pitteloud N, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC. Nonsense mutations in FGF8 gene causing different degrees of human gonadotropin-releasing deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3491–3496. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balmer CW, LaMantia AS. Noses and neurons: induction, morphogenesis, and neuronal differentiation in the peripheral olfactory pathway. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:464–481. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.LaMantia AS, Bhasin N, Rhodes K, Heemskerk J. Mesenchymal/epithelial induction mediates olfactory pathway formation. Neuron. 2000;28:411–425. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Graziadei PP, Monti Graziadei GA. Neurogenesis and plasticity of the olfactory sensory neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;457:127–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb20802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawauchi S, Beites CL, Crocker CE, Wu HH, Bonnin A, Murray R, Calof AL. Molecular signals regulating proliferation of stem and progenitor cells in mouse olfactory epithelium. Dev Neurosci. 2004;26:166–180. doi: 10.1159/000082135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carr VM, Farbman AI. Ablation of the olfactory bulb upregulates the rate of neurogenesis and induces precocious cell death in olfactory epithelium. Exp Neurol. 1992;115:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90221-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hinds JW, Hinds PL, McNelly NA. An autoradiographic study of the mouse olfactory epithelium: evidence for long-lived receptors. Anat Rec. 1984;210:375–383. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huard JM, Schwob JE. Cell cycle of globose basal cells in rat olfactory epithelium. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:17–26. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Newman MP, Feron F, Mackay-Sim A. Growth factor regulation of neurogenesis in adult olfactory epithelium. Neuroscience. 2000;99:343–350. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carter LA, MacDonald JL, Roskams AJ. Olfactory horizontal basal cells demonstrate a conserved multipotent progenitor phenotype. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5670–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0330-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo Z, Packard A, Krolewski RC, Harris MT, Manglapus GL, Schwob JE. Expression of Pax6 and Sox2 in adult olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4395–4418. doi: 10.1002/cne.22463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Farbman AI, Buchholz JA. Transforming growth factor-alpha and other growth factors stimulate cell division in olfactory epithelium in vitro. J Neurobiol. 1996;30:267–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199606)30:2<267::AID-NEU8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feron F, Bianco J, Ferguson I, Mackay-Sim A. Neurotrophin expression in the adult olfactory epithelium. Brain Res. 2008;1196:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leung CT, Coulombe PA, Reed RR. Contribution of olfactory neural stem cells to tissue maintenance and regeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:720–726. doi: 10.1038/nn1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beites CL, Kawauchi S, Crocker CE, Calof AL. Identification and molecular regulation of neural stem cells in the olfactory epithelium. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cau E, Gradwohl G, Casarosa S, Kageyama R, Guillemot F. Hes genes regulate sequential stages of neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium. Development. 2000;127:2323–2332. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guillemot F, Lo LC, Johnson JE, Auerbach A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell. 1993;75:463–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Delorme B, Nivet E, Gaillard J, Haupl T, Ringe J, Deveze A, Magnan J, Sohier J, Khrestchatisky M, Roman FS, Charbord P, Sensebe L, Layrolle P, Feron F. The human nose harbors a niche of olfactory ectomesenchymal stem cells displaying neurogenic and osteogenic properties. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:853–866. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Doyle KL, Kazda A, Hort Y, McKay SM, Oleskevich S. Differentiation of adult mouse olfactory precursor cells into hair cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:621–627. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Murrell W, Feron F, Wetzig A, Cameron N, Splatt K, Bellette B, Bianco J, Perry C, Lee G, Mackay-Sim A. Multipotent stem cells from adult olfactory mucosa. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:496–515. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nivet E, Vignes M, Girard SD, Pierrisnard C, Baril N, Deveze A, Magnan J, Lante F, Khrestchatisky M, Feron F, Roman FS. Engraftment of human nasal olfactory stem cells restores neuro-plasticity in mice with hippocampal lesions. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2808–2820. doi: 10.1172/JCI44489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tome M, Lindsay SL, Riddell JS, Barnett SC. Identification of nonepithelial multipotent cells in the embryonic olfactory mucosa. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2196–2208. doi: 10.1002/stem.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fernandes KJ, McKenzie IA, Mill P, Smith KM, Akhavan M, Barnabe-Heider F, Biernaskie J, Junek A, Kobayashi NR, Toma JG, Kaplan DR, Labosky PA, Rafuse V, Hui CC, Miller FD. A dermal niche for multipotent adult skin-derived precursor cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1082–1093. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blentic A, Tandon P, Payton S, Walshe J, Carney T, Kelsh RN, Mason I, Graham A. The emergence of ectomesenchyme. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:592–601. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Breau MA, Pietri T, Stemmler MP, Thiery JP, Weston JA. A nonneural epithelial domain of embryonic cranial neural folds gives rise to ectomesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7750–7755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711344105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Couly GF, Coltey PM, Le Douarin NM. The triple origin of skull in higher vertebrates: a study in quail-chick chimeras. Development. 1993;117:409–429. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fernandes KJ, Toma JG, Miller FD. Multipotent skin-derived precursors: adult neural crest-related precursors with therapeutic potential. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008;363:185–198. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Girard SD, Deveze A, Nivet E, Gepner B, Roman FS, Feron F. Isolating nasal olfactory stem cells from rodents or humans. J Vis Exp. 2011;54:2762. doi: 10.3791/2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Franklin RJ, Gilson JM, Franceschini IA, Barnett SC. Schwann cell-like myelination following transplantation of an olfactory bulb-ensheathing cell line into areas of demyelination in the adult CNS. Glia. 1996;17:217–224. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199607)17:3<217::AID-GLIA4>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ramon-Cueto A. Olfactory ensheathing glia transplantation into the injured spinal cord. Prog Brain Res. 2000;128:265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)28024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, Nave KA, Birchmeier C, Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Astic L, Pellier-Monnin V, Godinot F. Spatio-temporal patterns of ensheathing cell differentiation in the rat olfactory system during development. Neuroscience. 1998;84:295–307. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00496-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chehrehasa F, Ekberg JA, Lineburg K, Amaya D, Mackay-Sim A, St John JA. Two phases of replacement replenish the olfactory ensheathing cell population after injury in postnatal mice. Glia. 2012;60:322–332. doi: 10.1002/glia.22267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Honore A, Le Corre S, Derambure C, Normand R, Duclos C, Boyer O, Marie JP, Guerout N. Isolation, characterization, and genetic profiling of subpopulations of olfactory ensheathing cells from the olfactory bulb. Glia. 2012;60:404–413. doi: 10.1002/glia.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kueh JL, Raisman G, Li Y, Stevens R, Li D. Comparison of bulbar and mucosal olfactory ensheathing cells using FACS and simultaneous antigenic bivariate cell cycle analysis. Glia. 2011;59:1658–1671. doi: 10.1002/glia.21213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Paviot A, Guerout N, Bon-Mardion N, Duclos C, Jean L, Boyer O, Marie JP. Efficiency of laryngeal motor nerve repair is greater with bulbar than with mucosal olfactory ensheathing cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Richter MW, Fletcher PA, Liu J, Tetzlaff W, Roskams AJ. Lamina propria and olfactory bulb ensheathing cells exhibit differential integration and migration and promote differential axon sprouting in the lesioned spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10700–10711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Barnett SC. Olfactory ensheathing cells: unique glial cell types? J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:375–382. doi: 10.1089/089771504323004520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lakatos A, Franklin RJ, Barnett SC. Olfactory ensheathing cells and Schwann cells differ in their in vitro interactions with astrocytes. Glia. 2000;32:214–225. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200012)32:3<214::aid-glia20>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li BC, Xu C, Zhang JY, Li Y, Duan ZX. Differing Schwann cells and olfactory ensheathing cells behaviors, from interacting with astrocyte, produce similar improvements in contused rat spinal cord's motor function. J Mol Neurosci. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vincent AJ, Taylor JM, Choi-Lundberg DL, West AK, Chuah MI. Genetic expression profile of olfactory ensheathing cells is distinct from that of Schwann cells and astrocytes. Glia. 2005;51:132–147. doi: 10.1002/glia.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boyd JG, Jahed A, McDonald TG, Krol KM, Van Eyk JE, Doucette R, Kawaja MD. Proteomic evaluation reveals that olfactory ensheathing cells but not Schwann cells express calponin. Glia. 2006;53:434–440. doi: 10.1002/glia.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Franssen EH, De Bree FM, Essing AH, Ramon-Cueto A, Verhaagen J. Comparative gene expression profiling of olfactory ensheathing glia and Schwann cells indicates distinct tissue repair characteristics of olfactory ensheathing glia. Glia. 2008;56:1285–1298. doi: 10.1002/glia.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Norgren RB, Jr, Ratner N, Brackenbury R. Development of olfactory nerve glia defined by a monoclonal antibody specific for Schwann cells. Dev Dyn. 1992;194:231–238. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001940308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Takami T, Oudega M, Bates ML, Wood PM, Kleitman N, Bunge MB. Schwann cell but not olfactory ensheathing glia transplants improve hindlimb locomotor performance in the moderately contused adult rat thoracic spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6670–6681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06670.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Thompson RJ, Roberts B, Alexander CL, Williams SK, Barnett SC. Comparison of neuregulin-1 expression in olfactory ensheathing cells, Schwann cells and astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:172–185. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000715)61:2<172::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gasser C. Olfactory nerve fibres. J Gen Physiol. 1956;39:483–496. doi: 10.1085/jgp.39.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mendoza AS, Breipohl W, Miragall F. Cell migration from the chick olfactory placode: a light and electron microscopic study. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;69:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Doucette R. PNS-CNS transitional zone of the first cranial nerve. J Comp Neurol. 1991;312:451–466. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chuah MI, Au C. Olfactory Schwann cells are derived from precursor cells in the olfactory epithelium. J Neurosci Res. 1991;29:172–180. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490290206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Calof AL, Guevara JL. Cell lines derived from retrovirus mediated oncogene transduction into olfactory epithelium cultures. Neuroprotocols Companion Meth Neurosci. 1993;3:222–231. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mumm JS, Shou J, Calof AL. Colony-forming progenitors from mouse olfactory epithelium: evidence for feedback regulation of neuron production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11167–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Whitlock KE. A new model for olfactory placode development. Brain Behav Evol. 2004;64:126–140. doi: 10.1159/000079742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Basch ML, Bronner-Fraser M, Garcia-Castro MI. Specification of the neural crest occurs during gastrulation and requires Pax7. Nature. 2006;441:218–222. doi: 10.1038/nature04684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.D'Amico-Martel A, Noden DM. Contributions of placodal and neural crest cells to avian cranial peripheral ganglia. Am J Anat. 1983;166:445–468. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Collazo A, Fraser SE, Mabee PM. A dual embryonic origin for vertebrate mechanoreceptors. Science. 1994;264:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.8153631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Cis-acting regulatory sequences governing Wnt-1 expression in the developing mouse CNS. Development. 1994;120:2213–2224. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hebert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev Biol. 2000;222:296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Keilhoff G, Goihl A, Langnase K, Fansa H, Wolf G. Transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into Schwann cell-like myelinating cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Brand G. Olfactory/trigeminal interactions in nasal chemoreception. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:908–917. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Finger TE, Bottger B. Peripheral peptidergic fibers of the trigeminal nerve in the olfactory bulb of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334:117–124. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Schaefer ML, Bottger B, Silver WL, Finger TE. Trigeminal collaterals in the nasal epithelium and olfactory bulb: a potential route for direct modulation of olfactory information by trigeminal stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:221–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.10143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Silver WL, Finger TE. The anatomical and electrophysiological basis of peripheral nasal trigeminal chemoreception. Ann N YAcad Sci. 2009;1170:202–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Stone H, Rebert CS. Observations on trigeminal olfactory interactions. Brain Res. 1970;21:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rawson NE, Lischka FW, Yee KK, Peters AZ, Tucker ES, Meechan DW, Zirlinger M, Maynard TM, Burd GB, Dulac C, Pevny L, LaMantia AS. Specific mesenchymal/epithelial induction of olfactory receptor, vomeronasal, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1723–1738. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Carmona-Fontaine C, Acuna G, Ellwanger K, Niehrs C, Mayor R. Neural crests are actively precluded from the anterior neural fold by a novel inhibitory mechanism dependent on Dickkopf1 secreted by the prechordal mesoderm. Dev Biol. 2007;309:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Monsoro-Burq AH, Fletcher RB, Harland RM. Neural crest induction by paraxial mesoderm in Xenopus embryos requires FGF signals. Development. 2003;130:3111–3124. doi: 10.1242/dev.00531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Villanueva S, Glavic A, Ruiz P, Mayor R. Posteriorization by FGF, Wnt, and retinoic acid is required for neural crest induction. Dev Biol. 2002;241:289–301. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wu J, Yang J, Klein PS. Neural crest induction by the canonical Wnt pathway can be dissociated from anterior–posterior neural patterning in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2005;279:220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Brun RB. Neural fold and neural crest movement in the Mexican salamander Ambystoma mexicanum. J Exp Zool. 1985;234:57–61. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402340108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Au E, Roskams AJ. Olfactory ensheathing cells of the lamina propria in vivo and in vitro. Glia. 2003;41:224–236. doi: 10.1002/glia.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Northcutt RG, Gans C. The genesis of neural crest and epidermal placodes: a reinterpretation of vertebrate origins. Q Rev Biol. 1983;58:1–28. doi: 10.1086/413055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Williams MS. Speculations on the pathogenesis of CHARGE syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;133A:318–325. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Begbie J, Graham A. Integration between the epibranchial placodes and the hindbrain. Science. 2001;294:595–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1062028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shiau CE, Lwigale PY, Das RM, Wilson SA, Bronner-Fraser M. Robo2-Slit1 dependent cell-cell interactions mediate assembly of the trigeminal ganglion. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nn2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Fernandes KJ, Toma JG, Miller FD. Multipotent skin-derived precursors: adult neural crest-related precursors with therapeutic potential. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:185–198. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Roisen FJ, Klueber KM, Lu CL, Hatcher LM, Dozier A, Shields CB, Maguire S. Adult human olfactory stem cells. Brain Res. 2001;890:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Keyvan-Fouladi N, Raisman G, Li Y. Functional repair of the corticospinal tract by delayed transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9428–9434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09428.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Li Y, Field PM, Raisman G. Regeneration of adult rat corticospinal axons induced by transplanted olfactory ensheathing cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10514–10524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ramon-Cueto A, Nieto-Sampedro M. Regeneration into the spinal cord of transected dorsal root axons is promoted by ensheathing glia transplants. Exp Neurol. 1994;127:232–244. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Binder E, Rukavina M, Hassani H, Weber M, Nakatani H, Reiff T, Parras C, Taylor V, Rohrer H. Peripheral nervous system progenitors can be reprogrammed to produce myelinating oligodendrocytes and repair brain lesions. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:6379–6391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0129-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Dupin E, Calloni GW, Le Douarin NM. The cephalic neural crest of amniote vertebrates is composed of a large majority of precursors endowed with neural, melanocytic, chondrogenic and osteogenic potentialities. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:238–249. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.2.10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Dupin E, Calloni G, Real C, Goncalves-Trentin A, Le Douarin NM. Neural crest progenitors and stem cells. C R Biol. 2007;330:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Nagoshi N, Shibata S, Kubota Y, Nakamura M, Nagai Y, Satoh E, Morikawa S, Okada Y, Mabuchi Y, Katoh H, Okada S, Fukuda K, Suda T, Matsuzaki Y, Toyama Y, Okano H. Ontogeny and multipotency of neural crest-derived stem cells in mouse bone marrow, dorsal root ganglia, and whisker pad. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Real C, Glavieux-Pardanaud C, Vaigot P, Le-Douarin N, Dupin E. The instability of the neural crest phenotypes: Schwann cells can differentiate into myofibroblasts. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:151–159. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041940cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Widera D, Heimann P, Zander C, Imielski Y, Heidbreder M, Heilemann M, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Schwann cells can be reprogrammed to multipotency by culture. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:2053–2064. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Yang J, Lou Q, Huang R, Shen L, Chen Z. Dorsal root ganglion neurons induce transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells along a Schwann cell lineage. Neurosci Lett. 2008;445:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]