Abstract

This paper aims to report ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice. Health literacy is defined as the ability to access, understand, evaluate and communicate information as a way to promote, maintain and improve health in various settings over the life-course. A scoping study of the scientific and grey literature on health and, specifically, occupational therapy and health promotion was done from 1980 to May 2010. Five databases were searched by combining key words 1) “health literacy” with 2) “rehabilitation”, “occupational therapy” or “health promotion”. Data were extracted from 44 documents: five textbooks, nine reports and 29 articles. The literature on health literacy needs enhancing in both quantity and quality. Nevertheless, six ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice were identified (frequency; %): occupational therapists should 1) be informed about and recognize health literacy (27; 61.4), 2) standardize their practice (10; 22.7), 3) make information accessible (37; 84.1), 4) interact optimally with clients (26; 59.1), and 5) intervene (29; 65.9) and 6) collaborate to increase health literacy (21; 47.7). Since health literacy can directly impact intervention efficacy, further studies are needed on how to integrate health literacy into occupational therapy practice.

Keywords: Health education, health knowledge, attitudes, practice, communication, cooperative behavior, health determinant, literature review, empowerment, rehabilitation, health promotion, health services accessibility

Policy priorities (1, 2) and growing evidence indicate that health professionals, including occupational therapists (3), need to consider their clients’ level of health literacy in order to tailor their interventions accordingly and optimize their impact (4–8). “Literacy is the ability to understand and use reading, writing, speaking and other forms of communication as ways to participate in society and achieve one’s goals and potential. (p. 10)” (9). More specifically, health literacy is “[t]he ability to access, understand, evaluate and communicate information as a way to promote, maintain and improve health in a variety of settings across the life-course. (p. 11)” (9). Derived from health promotion, this definition of health literacy introduces a new dimension to capture and describe what influences the health choices that individuals make for themselves and others in their everyday lives. The concept of health literacy has emerged from two different roots: clinical care (as a clinical “risk”) and public health [as a personal “asset”; (7)]. On the one hand, poor literacy skills in clinical care are leading to various changes in clinical practice and organization. On the other hand, public health focuses on the development of skills and capacities intended to enable people to exert greater control over their health and the factors that shape health (7). Health literacy is so complex that even people with strong literacy skills may have difficulty obtaining, understanding, and using health information (10). From a health promotion perspective, health literacy has foundations consistent with occupational therapy in that it goes beyond individual abilities and considers the context and interactions in which these abilities are needed. Health literacy also highlights the importance of individuals developing more control over their health and its determinants (7, 11) to increase the likelihood that they will improve their health-related living conditions (12) and take appropriate health care decisions (10).

In addition to being a pillar of modern life (11, 13, 14), health literacy is one of the foundations of individual health (9). Since it affects everyday tasks [e.g. purchase food, plan exercise regimen, describe and measure symptoms, collect information on merits of various treatment regimes for discussion with health professionals, follow health professional recommendations (15)], low levels of health literacy have varied and serious consequences (9, 11). In fact, poor health literacy might be a better predictor of health status than education, socioeconomic status, employment, race or gender (16, 17). The possible consequences of poor health literacy range from lower levels of empowerment and participation to situations and behaviors that could jeopardize safety and health, i.e. increase morbidity and risk of premature mortality (9, 11, 16). An example of a behavior that jeopardizes safety and health would be when a client continues to use the stairs when the occupational therapist has strongly advised against it. People with low levels of health literacy might also have a reduced likelihood of achieving life goals and poorer quality of life. In addition, they might use more health services including hospitalization (9, 11, 16). Health literacy might also explain diverging results from educational intervention studies [e.g. (18, 19)]. Poor health literacy not only impacts individual health and development, it also has enormous economic, social and cultural consequences (11, 15, 16, 20). Low levels of health literacy are a widespread problem in many countries (9, 11). In the United States, Australia and Canada, for example, an estimated 46 to 60% of the population has a low level of health literacy (15–17, 21). Finally, health literacy has been identified as essential to optimizing the impact of health interventions and fostering clients’ long-term health.

The relevance of health literacy to rehabilitation (13, 22–24) or occupational therapy (1, 3, 25, 26) practice has been discussed in the literature. Rehabilitation is particularly linked to health literacy because both stress the importance of 1) capacities, functioning, participation and empowerment of clients; 2) holistic approach; 3) client-centered practice; 4) teaching of information and methods; and 5) access to services and equity issues (22). Given these links, occupational therapists are especially called upon and have specific competences to make a significant contribution to addressing health literacy challenges. To date, however, there is no detailed discussion in the scientific literature on ways to integrate health literacy into occupational therapy practice. This scoping review of the scientific and grey literature on rehabilitation, occupational therapy, health promotion and health literacy reports ways to incorporate health literacy in practice. This paper will help occupational therapists gain a better understanding of health literacy, identify the clinical implications and find ways to actively contribute to improving it.

Material and methods

To report ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice, a scoping review of the scientific and grey literature was conducted. In addition to the rehabilitation and occupational therapy literature, the review looked specifically at the health promotion literature. Derived from an area still generally underutilized by health professionals (27), the vision of health literacy in health promotion is more complete, holistic and proactive than that found in other health fields (7). Such a vision is, however, more complex to understand and difficult to measure. The methodology of scoping studies (28) was followed to conduct the literature review. Scoping studies are used to examine the extent, range and nature of publications in a particular field. It is a way to rapidly, systematically and extensively identify and numerically and narratively analyze a body of knowledge in the existing literature (28). The framework of scoping studies is a rigorous procedure that includes 5 stages: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. The Medline, OTDBASE, CINAHL, Allied & Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) and MANTIS databases were searched by combining the key words 1) “health literacy” with the key words 2) “rehabilitation”, “occupational therapy” or “health promotion” for the period from 1980 to May 2010. Papers were excluded if written in a language other than English or French. An extensive review of the titles and available abstracts identified all types of articles (empirical studies, conceptual articles, etc.) that might help identify what could be done to integrate health literacy. The search criteria were very inclusive to allow an extensive scoping of the field and, considering the limited body of knowledge on health literacy, provide as complete a portrait as possible (28). For the same reason, the key authors on health literacy in the health promotion field (Kickbusch, Rootman and Nutbeam), bibliographies and Websites were also included in the search strategy. Based on a discussion between the two authors, ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice were extracted by the first author from selected papers. Using content analysis (29), all data were then exhaustively analyzed, organized and synthesized by the first author and discussed with the co-author. Content analysis involved an extraction chart and identification of categories that best attributed meaning to the results, i.e. described ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice. Half of the content analysis was independently performed by the two authors and all discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Results are presented both numerically and narratively.

Results

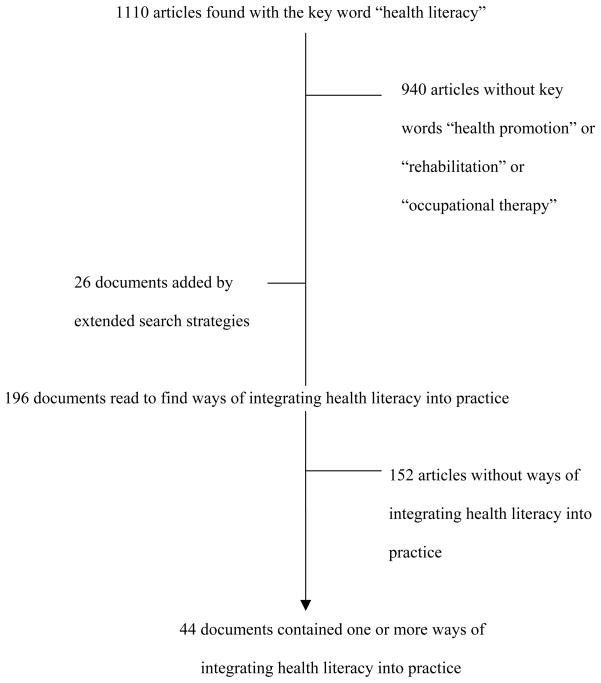

Of the 1110 articles found using the key words “health literacy”, 152 (13.7%) also included the key words “health promotion” and 22 (2.0%) included the key words “rehabilitation” or “occupational therapy” (Figure 1). Six of these articles (22, 24–26, 30, 31) (0.5%) included both categories of key words, but only one of these (26) was an empirical article where information was collected by means of observation, experience, or experiment. Of the sixteen other references that also included the rehabilitation or occupational therapy key words, nine articles (7, 8, 32–38) were not primarily concerned with occupational therapy or rehabilitation, and five others (23, 39–42) only touched on health literacy, one (1) was a position paper by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy, and the last (43) was an unpublished doctoral dissertation. In addition, two articles (13, 44) not picked up in the rehabilitation category also dealt with health literacy and rehabilitation, but without specifically discussing ways to integrate it into practice. All told and considering the documents added by the extended search strategies, thirteen articles, two reports and three textbooks addressed both health literacy and rehabilitation in sufficient detail. However, none provided a detailed and complete discussion about the various ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy or rehabilitation practice. The analysis of the scientific and grey literature was done on health literacy documents including, consecutively, health promotion, rehabilitation or occupational therapy. In all, 29 articles (65.9%), 9 reports (20.5%) and 5 textbooks (11.4%) were analyzed to identify how occupational therapists can adapt their practice to incorporate health literacy.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of articles retrieved to articles providing ways of integrating health literacy into practice

Most documents come from United States (n = 20; 45.5%) or Canada (n = 12; 25.0%). Year of publication of the documents ranged from 2000 to 2010. Of these, the majority were published after 2005, with the most productive years being 2005, 2007, 2008 and 2010 (n = 6, 8, 6 and 6 respectively). More than one quarter of the documents (n = 12) came from the field of public health and more than one third (n = 17) were specific to rehabilitation. Overall, a majority of the documents were conceptual in nature, i.e. review, textbook, or editorial (n = 33; 75.0%). Others reported empirical results (n = 11; 25.0%), mostly from quantitative cross-sectional (n =7; 15.9%) or qualitative (n = 3; 6.8%) studies.

Ways to integrate health literacy into occupational therapy practice

Six ways to integrate health literacy into occupational therapy practice were identified (Table 1): 1) Be informed about health literacy and recognize it; 2) Standardize practice to health literacy; 3) Consider health literacy by making information accessible; 4) Strengthen interactions; 5) Intervene to increase clients’ health literacy; and 6) Collaborate to increase clients’ health literacy. Of these six categories, four (1, 3, 4 and 5) were found in the majority of the documents (Table 1). The other two categories (2 and 6) were present in almost one quarter and one half of the documents, respectively. ‘Be informed’ refers to occupational therapists’ knowledge about and ability to identify challenging health literacy situations. ‘Standardize’ focuses on regulation and organization of occupational therapists’ interventions to systematically include health literacy. ‘Make accessible’ refers to the tips and skills that occupational therapists must use or develop to improve how they communicate the information to their clients, while ‘Strengthen interactions’ involve tips and skills that occupational therapists could use or develop to enhance the effectiveness of their clinical interventions. ‘Intervene’ specifically refers to interventions aimed at improving the client’s health literacy level, while ‘Collaborate’ refers to interventions that aim to improve a population’s health literacy level, in partnership with other actors. While ‘Strengthen interactions’ most often comes from rehabilitation documents, ‘Collaborate’ mostly comes from public health documents.

Table 1.

Strategies for occupational therapists to improve clients’ health literacy (n = 44)

| Categories of strategies (Frequency; %) | Examples of strategies |

|---|---|

| 1. Be informed about health literacy and recognize it (27; 61.4) |

|

| 2. Standardize practice to health literacy (10; 22.7) | |

| 3. Consider health literacy by making information accessible (37; 84.1) |

|

|

|

| 4. Strengthen interactions (26; 59.1) |

|

| 5. Intervene to increase client’s health literacy (29; 65.9) |

|

| 6. Collaborate to increase clients’ health literacy (21; 47.7) |

Discussion

The research on health literacy is undoubtedly in its early days, and the literature needs to be enhanced in both quantity and quality. Nevertheless, the documents found, including those on health promotion, provided some suggestions about ways to integrate health literacy into health professional and occupational therapy practice. Since the papers mostly come from industrialized countries, these results might be specific to Western countries.

To take advantage of all the opportunities to improve their clients’ health literacy, occupational therapists may take concrete action on various fronts (3, 24, 31) that use their essential competencies[(45); Table 1] For the most part, however, the impact of such actions has not been evaluated. Nevertheless, considering that low levels of health literacy is a widespread complex problem which has serious consequences (9, 11), occupational therapists may act now.

First, occupational therapists could be informed through university programs and professional development activities (9) about the issue of health literacy and its impact on interventions, the individual and society. Clients with low literacy levels are usually reluctant to ask questions and are skillful at hiding their problems (46). Although diverging opinions exist about whether (34, 44) or not (47, 48) clinicians may systematically evaluate clients’ health literacy, it is important to recognize individual and societal barriers to the promotion of health literacy (9). These barriers are: 1) functional declines associated with aging, 2) lack of reading and writing proficiency, 3) low levels of formal education or lack of health knowledge and skills, 4) different mother tongue or cultural beliefs (49), 5) living with disabilities and social stigma, and 6) experiences in early childhood. In addition to being informed, the national professional associations or regulatory/licensing bodies can contribute to developing professional standards and position statements that will help standardize the integration of health literacy into practice. In fact, all employees may value health literacy and it may be included in every health and medical care facility’s policies (3) and goals (50).

Next, it is important for occupational therapists to make their knowledge and services accessible (3, 7, 9, 11, 12, 24, 49). It has been shown that there is a gap between the reading level required for the majority of educational material used by occupational therapists and their clients’ reading and comprehension skills (26). The most common way to bridge this gap is to simplify the written material: shorten sentences to 10 words or less; use elementary concepts (corresponding to a grade 5 or 6 education; Table 2) with as few syllables as possible (ideally one or two), words that can be illustrated (audiovisually) and active verbs; and eliminate unnecessary words (9). This effort could be followed by a rigorous procedure including an evaluation of the readability of the material using, for example, the Fry Readability Scale (3) and verification with the target population (24). Some word processing programs (e.g. Microsoft Word) include an automatic function providing reading ease statistics (30, 32). There are also other resources such as editing services to clarify and simplify English texts (9). For example internationally, the International Reading Association provides a wide range of resources to support literacy professionals (51). Also in Canada, there are the National Literacy and Health Program and the Centre for Literacy of Québec. Although such efforts are important, there is no evidence that simplifying written material improves clinical outcomes, in part because research on the subject is still scarce and methodological challenges in studying this complex subject are numerous (52). Nevertheless, occupational therapists may simplify written material. Health literacy is fostered by adapting the information to individual needs and circumstances (3, 5, 11) and using anecdotal information from everyday life presented as personal stories (31). Occupational therapists may also interact and intervene (Table 2) to improve health literacy.

Table 2.

Five key clinical messages

|

Interactions between clients and occupational therapists could be optimized (3, 7). This optimization is one of the occupational therapists’ responsibilities and may be encouraged by the practice setting (50). To help their clients understand, occupational therapists can improve their own ability to communicate in clear, simple (4, 5) and culturally competent language, which is an essential competency for their practice (45, 53). When exchanging information with them, it is important to be aware of clients’ perceived powerlessness (54), culture, attitudes, and priorities as well as obstacles (5) to rehabilitation interventions. For example, it is important to identify clients’ false beliefs and understand their emotions and motivation (3, 47, 55). In addition, being informed about cultural differences and using an interpreter can be helpful in interacting effectively (49).

Occupational therapists can also, through educational and social marketing interventions, increase their clients’ health literacy and consequently their empowerment and participation. They can intervene in schools to optimize children’s learning skills and improve literacy. Also, improving health literacy involves more than transmitting health information, although this is still an essential task (56). Occupational therapists’ interventions could allow the client to develop: 1) knowledge that is adapted to his/her age and situation (including consideration of his/her personal experience), and 2) a feeling of self-efficacy in applying this knowledge (7, 56). More personal forms of communication encourage this development (20). As a result, clients might be empowered by achieving a certain level of knowledge (e.g. social determinants of health, signs and symptoms of disease, etc.), personal competencies and confidence in their ability to act and participate. Fostering the acquisition of skills to enable clients to interact with health professionals (3) will also develop people’s capacities in effectively navigating through and actively participating in the health system and their community (11). In addition to intervening to empower their clients, occupational therapists can also foster the empowerment of families and even communities (57).

Finally, the health literacy issue requires a public health effort involving the close collaboration of various disciplines, including rehabilitation. Occupational therapists can have an important advocacy role in influencing the goals of their health facility regarding health literacy (3) and participate actively in public health initiatives and research on health literacy (Table 2). They could help raise awareness among other players in clinical settings (3) and the organization of care (other stakeholders, support staff and managers), and community partners (5, 7, 11). For example, they can 1) get involved on the social or political level in defending their clients’ interests or showing leadership with regard to all health determinants (27, 58), including health literacy; 2) participate in community initiatives to improve people’s reading, writing and math skills (5); 3) work to reduce the complexity of the organization of health services (3, 54); 4) reduce resistance to change in society (59); and 5) educate other health professionals about health literacy issues (3). Current changes that lead to increased responsibility of the health system and policies regarding the health of the population are conducive to the integration of actions aimed at considering and intervening to improve health literacy.

Further research is needed on the determinants of health literacy, people’s habits with regard to accessing health information (9, 11) and the effectiveness of innovative interventions to improve health literacy (9, 11). Occupational therapists can collaborate in designing and implementing such research projects. We also need a better understanding of gender differences, and the relationship between health literacy and 1) chronic diseases requiring lifestyle changes, and 2) some clinical outcomes. Therefore, research on disease self-management programs could consider health literacy. It is also important to improve the operationalization of the concept for both research and clinical purposes (56) and the framework for research development (52). There is still a lot of work to be done to develop a more comprehensive measure to evaluate people’s level of health literacy in terms of their ability to access, understand and use health information in a way that promotes and maintains good health (7) and to evaluate rehabilitation programs’ health literacy level (3). Finally, research on clinical outcomes of interventions integrating health literacy could address efficacy and effectiveness issues, which has not been done so far (3).

In short, occupational therapists could consider if their actions are consistent with these ways to improve health literacy (Table 2). Through such actions, they can act on various levels (60); for example, they can 1) intervene directly with disadvantaged individuals (onto) and their immediate environment (micro), 2) take action with local communities, including the organization of the health system (micro), and 3) influence local, national and global authorities (micro and meso), and 4) be aware of and consider beliefs and culture, including their own [macro; (57, 61)]. Improving health literacy thus requires concerted action at many levels (7).

Strengths and limitations

This study systematically reviewed health literacy articles from the rehabilitation and health promotion literature. Using the rigorous procedures of scoping studies, heterogenous documents were synthesized to discuss ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy practice. However, the scoping study methodology is not intended to systematically combine the results of previous studies or to appraise the quality of the evidence. Even if a rigorous and innovative procedure involving two persons was used to analyze the content of the literature, the importance the authors attribute to each theme might have influenced the content of the synthesis. Moreover, the electronic search did not specifically include other potentially interesting concepts such as “literacy” and “illiteracy” per se. Finally, the number of rehabilitation papers on health literacy is small (n = 17) and since ways of integrating health literacy were, for the most part, not based on empirical evidence, further research is needed to evaluate the interventions synthesized in the present scoping study. Nevertheless, even though research could continue, in the meantime occupational therapists may integrate health literacy into their practice.

Conclusion

Internationally, the low level of health literacy in the population is a serious problem requiring innovative and proactive initiatives. Despite major policy reports on the urgent need to improve health literacy, little improvement has been made (46). Health professionals in general, and occupational therapists in particular because of our specific competencies, may act. We could work hard to increase health education, improve health communication and foster a client-centered approach to promote a health literate society and reduce health inequalities (46). Health literacy enables clients and occupational therapists to engage in a true dialogue fostering: 1) a common perspective on how to address the situation, 2) listening, 3) mutual learning, and 4) a climate of trust and partnership (5). Given the impact of health literacy on interventions, the individual and society, occupational therapists could seize every opportunity to improve it. To do so, we need to be informed, standardize practice, make rehabilitation information and services accessible, and interact optimally with clients. For example, creating readable client educational material is important in improving health literacy (46). We could also intervene and collaborate to increase the health literacy of our clients and of the population in general and raise awareness regarding the importance of health literacy among health care professionals. It is also important to avoid certain mistakes made in health education, such as taking a reductionist approach to health literacy, limited development of personal competencies, and investing only in information, education and communication (62). Emphasizing empowerment, self-confidence, feelings of personal efficacy and being in control, and a range of skills (e.g. reading and writing skills) might be the key to success. These characteristics give individuals more control over their health and environment and the ability to make healthy choices (63). However, these choices and the resulting health behaviors will only be possible if individuals have sufficient knowledge and understanding of health and its determinants (11, 63) and a supportive environment.

Research could continue so that occupational therapists base their actions on the best possible evidence. It is also important to make a concerted effort to improve the health literacy of individuals and communities. Improving health literacy could lead not only to personal benefits but also to social benefits (59). The potential impacts of improving the health literacy of the population are wide-ranging and substantial: increase in general population health; decline in the use of health services; reduction in average costs of treatment including shorter treatment times and fewer errors; decline in work accidents; increased productivity; growth in the country’s economy; and reduction in health inequities (15). Therefore it is important that we, as occupational therapists, integrate health literacy into our practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kate Frohlich, Lise Gauvin, Louisette Mercier and Irene Ilott for their suggestions and comments on a preliminary version of this article. The Léa-Roback Research Centre on Social Inequities in Health of Montréal provided financial support for the translation of this paper.

Footnotes

Note: The references that were used to specifically extract ways of integrating health literacy into occupational therapy are the following: 1–5, 7–15, 17, 20, 22–27, 30–32, 34–37, 43, 44, 46–48, 50, 51, 55, 56, 59, 62–66.

References

- 1.Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. CAOT Position Statement Health and Literacy. Ottawa (Ontario): Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC: 2010. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DL, Hedrick W, Earhart H, Galloway H, Arndt A. Evaluating two health care facilities’ ability to meet health literacy needs: A role for occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2010;24(4):348–59. doi: 10.3109/07380577.2010.507267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI at Forefront of National Program to Advance Patient Self-Management of Care. Cambridge, MA: 2007. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kickbusch I, Wait S, Maag D. Navigating Health: The Role of Health Literacy. London: 2005. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McQueen DV. Critical Issues in Theory for Health Promotion. In: McQueen DV, Kickbusch I, Potvin L, Pelikan JM, Balbo L, Abel T, editors. Health Modernity The role of theory in health promotion. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008 Dec;67(12):2072–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rootman I. Health promotion and literacy: implications for nursing. Can J Nurs Res. 2004 Mar;36(1):13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rootman I, Gordon-El-Bihbety D. Report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy. Ottawa (Ontario): 2008. A vision for a Health Literate Canada. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002 May;40(5):395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kickbusch I, Maag D. Health Literacy. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008:204–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel T. Cultural Capital in Health Promotion. In: McQueen DV, Kickbusch I, Potvin L, Pelikan JM, Balbo L, Abel T, editors. Health Modernity. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston MV, Diab ME, Kim SS, Kirshblum S. Health literacy, morbidity, and quality of life among individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28(3):230–40. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2005.11753817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kickbusch I. Health Governance: The Health Society. In: McQueen DV, Kickbusch I, Potvin L, Pelikan JM, Balbo L, Abel T, editors. Health Modernity. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Council on Learning. Initial results from the International Adult Literacy and Skills Survey. 2007. Health literacy in Canada. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keheler H. Turning the key on health literacy to achieve better health outcomes. CDN Conference Darwin; 2009 September 10; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keheler H, Hagger V. Health Literacy in Primary Health Care. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2007;13(2):24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Hara L, Cadbury H, De SL, Ide L. Evaluation of the effectiveness of professionally guided self-care for people with multiple sclerosis living in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2002;16:119–28. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr478oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward CD, Turpin G, Dewey ME, Fleming S, Hurwitz B, Ratib S, et al. Education for people with progressive neurological conditions can have negative effects: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2004;18:717–25. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr792oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15(3):259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Assessment of Adult Literacy. A Nationally Representative and Continuing Assessment of English Language Literacy Skills of American Adults. 2003. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levasseur M, Carrier A. Do rehabilitation professionals need to consider their clients’ health literacy for effective practice? Clin Rehabil. 2010 Aug;24(8):756–65. doi: 10.1177/0269215509360752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magasi S, Durkin E, Wolf MS, Deutsch A. Rehabilitation consumers’ use and understanding of quality information: a health literacy perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Feb;90(2):206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanderhoff M. Patient education and health literacy. Physical Therapy. 2005;13(9):42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa DM. Facilitating health literacy. OT Practice. 2008;13(15):13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin J, McKenna K, Tooth L. Discrepancy between older clients’ ability to read and comprehend and the reading level of written educational materials used by occupational therapists. Am J Occup Ther. 2006 Jan-Feb;60(1):70–80. doi: 10.5014/ajot.60.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hills M, Carroll S, Vollman A. Health Promotion and Health Professions in Canada: Toward a Shared Vision. In: O’Neill M, Dupéré SAP, Rootman I, editors. Health promotion in Canada Critical perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc; 2007. pp. 330–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.L’Écuyer R. Méthodologie de l’analyse développementale de contenu : méthode GPS et concept de soi [Methodology of developmental content analysis: GPS method and self concept] Québec, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin J, McKenna K, Tooth L. Written health education materials: Making them more effective. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2003;50:170–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath T. Health Literacy: Implications for Client-Centred Practice - Insights from a health promotion pilot project. Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;33(2):2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billek-Sawhney B, Reicherter EA. Literacy and the older adult: Educational considerations for health professionals. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2005;21(4):275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenhalgh T, Wood GW, Bratan T, Stramer K, Hinder S. Patients’ attitudes to the summary care record and HealthSpace: qualitative study. BMJ. 2008 Jun 7;336(7656):1290–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med [Review] 2009 Sep;121(5):171–7. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.09.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborne H. Health literacy: how visuals can help tell the healthcare story. J Vis Commun Med. 2006 Mar;29(1):28–32. doi: 10.1080/01405110600772830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rootman I, Edwards P. As the ship sails forth. Can J Public Health. 2006 May-Jun;97(Suppl 2):S43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rootman I, Ronson B. Literacy and health research in Canada: where have we been and where should we go? Can J Public Health. 2005 Mar-Apr;96(Suppl 2):S62–77. doi: 10.1007/BF03403703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.St John W, Wallis M, James H, McKenzie S, Guyatt S. Targeting community-dwelling urinary incontinence sufferers: a multi-disciplinary community based model for conservative continence services. Contemp Nurse. 2004 Oct;17(3):211–22. doi: 10.5172/conu.17.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anglin C. Providing pediatric psychosocial support through patient library services in an outpatient hematology/oncology clinic. Primary Psychiatry. 2008;15(7):78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moghimi C. Issues in caregiving: The role of occupational therapy in caregiver training. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2007;23(3):269–79. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasson R, Grinshpoon A, Lachman M, Ponizovsky A. A program of supported education for adult Israeli students with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005 Fall;29(2):139–41. doi: 10.2975/29.2005.139.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith CM, Pristach CA. Management of psychiatric disorders in patients with poor insight. Disease Management and Health Outcomes. 1998;4(3):157–75. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamel PC. Communication and health literacy: a changing focus in physical therapist education [Research] Boston: Boston University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hahn EA, Cella D. Health outcomes assessment in vulnerable populations: measurement challenges and recommendations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Apr;84(4 Suppl 2):S35–42. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Profile of occupational therapy practice in Canada. Ottawa (Ontario): Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2007. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dreeben O. Patient Education and Communication Variables. In: Dreeben O, editor. Patient education in rehabilitation. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2010. pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauthier J. Le patient aux prises avec des problèmes d’alphabétisme fonctionnel [Patients with functional literacy problems] In: Richard C, Lussier M-T, editors. La communication professionnelle en santé [Professional communication in health] Saint-Laurent (Québec): Éditions du Renouveau Pédagogiques Inc; 2005. pp. 401–25. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lurie N, Parker R. Editorial: moving health literacy from the individual to the community. Am J Health Behav. 2007 Sep-Oct;31(Suppl 1):S6–7. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) Guiding Principles on Diversity and Culture. Forrestfield WFOT; 2009. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, D.C: National Academy of Sciences; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Reading Association. About the International Reading Association: The World’s Leading Organization of Literacy Professionals. 2010 Jul 12;2010 Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCaffery KJ, Smith SK, Wolf M. The Challenge of Shared Decision Making Among Patients With Lower Literacy: A Framework for Research and Development. Med Decis Making. 2010 Aug 19;30(1):35–44. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Occupational Therapy Association. Position Paper: Scope of Practice. 2009. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Townsend E. Reflections on power and justice in enabling occupation. Can J Occup Ther. 2003 Apr;70(2):74–87. doi: 10.1177/000841740307000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phaneuf M. Communication, entretien, relation d’aide et validation [Communication, discussion, help relation and validation] Montréal (Québec): Les Éditions de la Chenelière inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nutbeam D, Kickbusch I. Advancing health literacy: a global challenge for the 21st century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15(3):183–4. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Townsend E. Nicole Ébacher Address. Vol. 2009. Université Laval; Dec, 2009. The world at our feet: Walking the global talk of collaborative, experience-based practices; p. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Townsend E. Occupational therapy language: Matters of respect, accountability and leadership. Canadian journal of occupational therapy. 1998;65(1):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rootman I, Frankish J, Kaszap M. Health Literacy: A New Frontier. In: O’Neill M, Dupéré SAP, Rootman I, editors. Health promotion in Canada Critical perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc; 2007. pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Restall G, Ripat J, Stern M. A framework of strategies for client-centred practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2003 Apr;70(2):103–12. doi: 10.1177/000841740307000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nutbeam D. What would the Ottawa Charter look like if it were written today? Critical Public Health. 2008;18(4):435–41. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Green J. Health education-the case for rehabilitation. Critical Public Health. 2008;18(4):447–56. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lagarde F. Les clés d’une communication-santé réussie [The keys to successful health communication]. Journées annuelles de santé publiques [Annual public health days]; 10 mars 2010; Montréal (Qc). 2010. p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Browning N. Literacy of children with physical disabilities: a literature review. Can J Occup Ther. 2002 Jun;69(3):176–82. doi: 10.1177/000841740206900308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rothschild B. Health literacy: what the issue is, what is happening, and what can be done. Health Promot Pract. 2005 Jan;6(1):8–11. doi: 10.1177/1524839904270387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]