Abstract

Objectives

The drug-related locus of control scale (DR-LOC) is a new instrument for assessing a person’s belief of “being in control” in situations involving drug abuse. It consists of 16-item pairs presented in a forced-choice format, based on the conceptual model outlined by Rotter. The model characterizes the extent to which a person believes that the outcome of an event is under their personal control (internal locus of control) or the influence of external circumstances (external locus of control).

Methods

A total of 592 volunteers completed the DR-LOC and the Rotter’s I-E scale. Approximately half of the respondents were enrolled in a drug treatment program for opiates, stimulants and/or alcohol dependence (n = 282), and the remainder (n = 310) had no history of drug dependence.

Results

Factor analysis of DR-LOC items revealed 2 factors reflecting control beliefs regarding (i) the successful recovery from addiction, and (ii) decisions to use drugs. The extent to which a person attributes control in drug-related situations is significantly influenced by their personal or professional experiences with drug addiction. Drug-dependent individuals have a greater internal sense of control with regard to addiction recovery or drug-taking behaviors than health professionals and/or non-dependent control volunteers.

Conclusions

The DR-LOC has shown to effectively translate generalized expectancies of control into a measure of control expectancies for drug-related situations, making it more sensitive for drug-dependent individuals than Rotter’s I-E scale. Further research is needed to demonstrate its performance at discriminating between heterogeneous clinical groups such as between treatment-seeking versus non–treatment-seeking drug users.

Keywords: substance abuse, self-report measure, addiction recovery, drug-taking, health professionals

Drug addiction is a chronically relapsing disorder, characterized by a compulsive drive to seek drugs and a loss of control over drug intake.1 Multiple lines of evidence indicate that drug addiction is associated with significant disruptions in brain systems underlying self-control.2,3 For example, substance-dependent individuals demonstrate significant impairment in the control of behavior,4–6 attention,7–9 and other cognitive functions.10,11 These neurocognitive impairments have a considerable impact on the effectiveness of treatment,12–14 but drug users often lack insight into the extent of their cognitive deficits.15,16 Their beliefs of being in control, rather than their actual abilities, seem to play an important role in their engagement in treatment and determine their efforts in maintaining drug abstinence.17 The assessment of control beliefs of drug-dependent individuals may provide useful information for clinicians concerned with the treatment of drug users and also for researchers investigating drug users’ impairments in executive function.

The psychological concept of locus of control (LOC) reflects the belief of being in control, that is, the degree to which a person feels that rewards in life are contingent on their own behavior, or by contrast, are controlled by other people or external forces.18 LOC was initially formulated as an unidimensional construct representing a single continuum from internal to external sources of control and is measured by Rotter’s internal-external (I-E) scale. On the I-E scale, a person’s generalized control beliefs are reflected by a single score ranging from highly internal to highly external.18 Internally controlled individuals believe that successes or failures in life are due to their own efforts and abilities, whereas those with an external sense of control believe that control is out of their hands and that outcomes in life are determined by forces such as other people, luck or fate.18

To account for the variability of control experiences in different contexts, the LOC concept has been adapted to specific domains such as health,19 work,20 and drinking behavior,21 to mention a few. The drink-related LOC scale (DRIE),21 for example, takes into consideration the distinctive situations that are associated with the LOC in alcohol dependence. As one may expect, alcohol-dependent individuals report having more external control beliefs in alcohol-related situations compared with recovering alcoholics, who score more “externally” on the DRIE than social drinkers.22 The DRIE, however, is not without critics, in particular because of its mixture of both personalized (eg, “Once I start drinking I cannot stop”) and general statements (eg, “If people want something badly enough, they can change their drinking behaviour”). Alcohol-dependent patients have shown to make an external-to-internal shift in scoring on the DRIE during treatment,23 but this change may be confounded by the fact that personalized items may not be sensitive when alcohol is no longer consumed. General statements about drinking might be more appropriate for measuring changes in control beliefs. The DRIE scale has been transferred to drug-related situations by exchanging the world “alcohol” with the word “drug,”24–26 producing similar results to prior studies on the DRIE in alcohol-dependent populations. However, the problem with personalized items has not been addressed by any of the drug-related scales.

The aim of the present study was to develop a brief instrument to assess control beliefs with regard to drug-taking behaviors [drug-related locus of control (DR-LOC)] using only general statements, which has 2 advantages: (i) control beliefs can be assessed in drug users independently from their current drug-taking habits; and (ii) control beliefs can be measured in both drug using and non–drug-using individuals. The latter was a shortcoming for previous DR-LOC measures that were not suitable for non-drug users. We hypothesized that drug-dependent individuals would ascribe more control over their drug use to external forces (ie, deferring responsibility to others or external events rather than to themselves) compared with people who have never excessively used drugs. We will further explore whether a professional contact with drug users influences peoples’ persceptions of LOC in a drug-related context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample, Instruments, and Procedures

A total of 592 volunteers living in the East Anglia region of the UK completed the DR-LOC questionnaire and the Rotter’s I-E scale.18 The overwhelming majority of volunteers were of white race (89%), most of them were male (61% men, 39% women), and the mean age was 35.1 years (SD ± 11.7).

Approximately half of the volunteers were currently enrolled in an outpatient treatment program for opiates, stimulants, and alcohol dependence (n = 310). These individuals were recruited because of their problematic drug-taking history. Drug-dependent volunteers were approached at treatment services in the East Anglia region, including London (UK) by clinically trained staff from the Mental Health Research Network (http://www.mhrn.info/). The other half of the sample (n = 282) were recruited through the healthy volunteer panel at the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute and by word of mouth within the local community. The control volunteers reported no personal history of substance dependence. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants. The study was approved by the NHS Cambridgeshire 2 Research Ethics Committee and the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee and has been performed in accordance with the Ethical Standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki.

All volunteers completed the 2 aforementioned questionnaires and provided further information, including their age, gender, years of education, and ethnic group by self-report. The initial DR-LOC contained 25-item pairs presented in a forced-choice format. Each pairing contained 1 statement indicating an internal control belief (eg, “Those who are successful in getting off drugs are often the lucky ones”) and 1 statement indicative of an external control belief (eg, “Getting off drugs depends upon lots of effort and hard work; luck has nothing to do with it”). Volunteers were instructed to choose the statement in each pair that most accurately described their current beliefs. The questionnaire items were presented in a balanced manner. Individual items were binary scored as either 0 (internal) or 1 (external). Rotter’s I-E scale,18 which measures generalized control beliefs in a neutral context,18,27 was included for comparison with responses in a drug-related context. We decided a priori to remove the 3 items of the I-E scale referring to situations at school, as these 3 items have been found inappropriate for adult samples.28

Statistical Analysis

Group comparisons on demographic data were performed using t tests and χ2 methods, as appropriate, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 13 (SPSS Inc.).

The response data from the initial 25-item DR-LOC questionnaire (shown in the Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/ADTT/A1) were evaluated separately using exploratory factor analysis for binary data using maximum likelihood estimation in modern psychometric software. We used 12 integration points per dimension to increase the accuracy of the model. A χ2 (likelihood ratio test) determined the number of factors. Whist items with low factor loadings (below 0.3) were removed, meaningful factors were retained and interpreted based on their LOC concepts and theory. For completeness, factorial validity of each DR-LOC item was assessed simultaneously by both confirmatory factor analysis and a 2-parameter logistic item response model (both assuming a normal distribution for the latent factor continuum). We then used a more constrained (1-parameter) logistic model for the estimation of latent factor scores for all respondents. Internal consistency coefficients (lower bound estimates of reliability, under a restrictive test model) was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha for each factor as well as the composite reliability of the whole scale (within generalizability theory framework). The latter provides a more valid reliability estimate for these data. Psychometric modeling was performed using Mplus,29 BILOG,30 and mGENOVA.31

The final version of the DR-LOC questionnaire, retained items that loaded on 1 of 2 factors; each of the factors were loaded by 8 items (Table 1). These factors and the Rotter’s I-E were subject to group comparisons. The total scores of the Rotter’s I-E and the DR-LOC were analyzed using analysis of covariance; gender was included as a covariate. For group comparisons on the 2 DR-LOC subscales, multivariate analysis of covariance was conducted, also adjusting for gender. The least significant differences test was used to examine post hoc differences amongst the groups (ie, drug-dependent volunteers, health professionals, non-dependent healthy volunteers). Pearson correlations were performed where appropriate. All tests were 2-tailed and a significance level of 0.05 was assumed.

TABLE 1.

Items of the DR-LOC Questionnaire, Including the Instructions for Participants and Scoring Information

| Instructions: This questionnaire assesses your opinion about drugs and drug use. Each item consists of a pair of alternatives marked with a or b. |

|

| Since this is an assessment of opinions, there are obviously no right or wrong answers. |

|

| Scoring |

| DR-LOC addiction recovery: 3a, 4a, 5a, 7b, 11a, 14a, 15b, 16a |

| DR-LOC drug-taking decisions: 1b, 2a, 6b, 8b, 9a, 10b, 12b, 13a |

DR-LOC indicates drug-related locus of control scale.

RESULTS

Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure of the DR-LOC

The likelihood ratio test of the exploratory factor analysis results revealed that a 2-factor solution was superior to the single unidimensional solution (χ2 = 196.8, df = 29, P<0.001). A 3-factor solution was not indicated over 2 factors (χ2 = 12.9, df = 16, P = 0.68). Interfactor correlation was moderate, at r = − 0.39. The first factor (addiction recovery) contained 8 items, reflecting the extent to which an individual believes that recovery from addiction is determined by their personal efforts rather than by the support provided from other people. The second factor (drug-taking decisions) also contained 8 items and measured the extent to which a person believes that the decision to take drugs is under their own personal control rather than determined by peer pressure, or external needs or problems. Nine items did not load on any of the 2 factors (loadings <0.3) and therefore were excluded from the final scale.

After the exclusion of items with low factor loadings, we applied a more restrictive 1-parameter logistic model, to simplify the interpretation of raw scores and further justify the use of summary scores. The 1-parameter logistic model is a more restrictive model, but model comparisons showed a non-significant decrease of model fit for both DR-LOC factors [ie, the deviance test with 8 degrees of freedom equals to 8.7 (P = 0.46) for addiction recovery, and to 10.7 (P = 0.21) for drug-taking decisions]. Further, graphical inspection supported this simpler model. No gross indications of misfit between any of the individual items and either the empirical item characteristic curve or the modeled item characteristic curve (see also Figure S1) were identified. This provided further support for the use of summary scores within each factor.

Internal consistency of the DR-LOC, as estimated by Cronbach’s alpha, was relatively low for addiction recovery (α = 0.48) and moderate for drug-taking decisions (α = 0.60), reflecting the breadth of the construct measured by these items. Reliability of the whole scale, as estimated by composite Cronbach’s alpha (yield 0.62), which is quite low, but still comparable with LOC measures previously used in drug user samples.26 Although Cronbach’s alpha has been considered the gold standard of indexing reliability, it may be challenged when the number of items are low and when the sampling errors impact on the range of candidate ability. In the present study, we did not find evidence that the SEM was affected by these problems as the SEM yielded 1.06 for addiction recovery and 1.19 for drug-taking decisions. The DR-LOC may therefore be an appropriate measure and could be recommended for routine use, but only for comparing quite large groups (n>100). Further details about the psychometric properties can be obtained from the authors (K.D.E., J.S.).

Study Sample

Volunteers with and without a drug dependency problem did not significantly differ from each other in terms of age (t456.2 = 0.96, P = 0.337) or ethnicity (χ2 = 2.67, P = 0.102). There was, however, a significant difference in the gender ratio (χ2 = 49.22, P<0.001); while in the control group the ratio of men (46%) and women (54%) was almost equally balanced; the drug user group was predominantly male (75% men, 25% women). Consequently, all group comparisons are reported after adjustment for main effects of gender. Drug users reported significantly fewer years of education (mean: 10.4 y, SD ± 2.7) compared with control volunteers (mean: 12.7 y, SD ± 2.5) (t567 = 10.01, P<0.001); this is a common finding, which has also been reported previously.32 As years of education were not correlated with either the DR-LOC scores (r = 0.003, P = 0.946) or the I-E total scores (r = − 0.01, P = 0.789), education was not included as a covariate in further analyses.

Twenty percent of non-dependent volunteers (eg, nurses, key workers, general practitioners) reported having professional contact with chronic drug users. This subgroup of volunteers was slightly older (mean: 39.4 y, SD ± 12.1) than those without professional contact with drug users (mean: 34.6 y, SD ± 14.5) (t272 = 2.34, P = 0.020). However, age was not correlated with DR-LOC (r = − 0.0.03, P = 0.676) or the I-E scale (r = 0.0.07, P = 0.226) within the group of non-dependent volunteers and therefore was not included as a covariate in further analyses. Neither years of education (t261 = − 4.14, P = 0.680), nor the gender ratio (χ2 = 2.0, P = 0.157) differed between these 2 subgroups.

Drug-related Control Orientation With Regard to Personal Experience of Addiction

The drug-dependent individuals reported significantly greater levels of internal control in a drug-related context (mean score: 8.8, SD ± 2.5) compared with non-dependent volunteers (mean: 9.3, SD ± 2.8; F1,577 = 5.09; P = 0.024). This significant difference was due to drug users having an internal sense of control in terms of addiction recovery compared with the non-dependent volunteers (drug users: 6.1, SD ± 1.5; volunteers: 6.5, SD ± 1.4; F1,577 = 12.80; P<0.001). No group difference was observed on the DR-LOC decision-making subscale (drug users: 2.7, SD ± 1.8; volunteers: 2.7, SD ± 2.1; F1,577 = 0.13; P = 0.719). Generalized control beliefs, as measured by Rotter’s I-E scale did not significantly differ between the groups (drug users: 9.2, SD ± 3.2; volunteers: 9.5, SD ± 3.6; F1,577 = 3.43; P = 0.065). The inclusion of the Rotter’s I-E score as a covariate in the analysis of the DR-LOC subscales, to control for variances in generalized control beliefs, did not change the results on the DR-LOC. This is consistent with the notion that drug-related control beliefs are domain specific and not explained by general control beliefs. Yet, Rotter’s I-E scale and the DR-LOC were not independent, rather they weakly correlated with each other (r = 0.27, P<0.001).

Experience With Drug-addicted Individuals and Drug-related Control Orientation

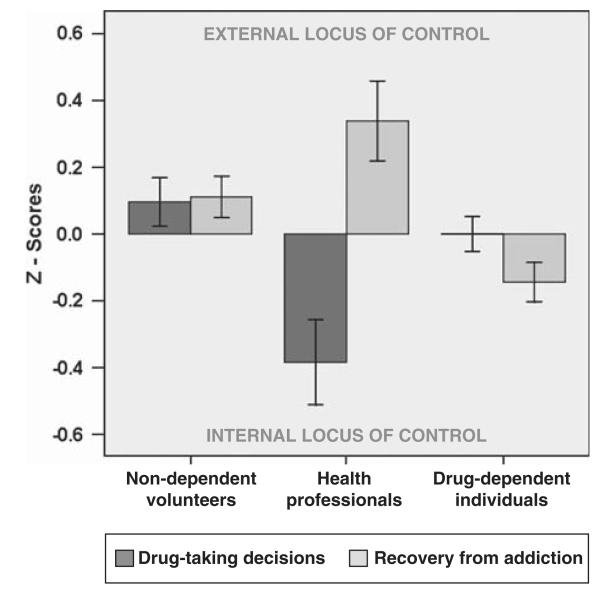

Comparisons between drug users and the 2 subgroups of non-dependent volunteers revealed a significant difference in drug-related control beliefs (F2,576 = 3.70, P = 0.025), but not in terms of generalized control beliefs (F2,576 = 2.22, P = 0.109). Group differences on the DR-LOC were reflected on both subscales. Thus beliefs of “being in control” when deciding to take drugs differed significantly between the groups (F2,576 = 5.19, P = 0.006). As shown in Figure 1, health professionals were significantly more internally orientated when compared with their non-professional counterparts (P = 0.001), and also when compared with the drug users (P = 0.018). However, control beliefs between non-professional volunteers and the drug users did not differ (P = 0.167). There was also a significant group difference in terms of control beliefs regarding addiction recovery (F2,576 = 7.45, P = 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that drug users were significantly more internally controlled when separately compared with either health professionals (P = 0.001) or non-professional volunteers (P = 0.004), while the beliefs in the 2 non-dependent groups were similar (P = 0.150). The significant group differences on both subscales and post hoc tests survived when the analysis was corrected for generalized LOC beliefs using the Rotter’s I-E score as a covariate.

FIGURE 1.

Standardized responses of the drug-related locus of control scale (DR-LOC) in drug-dependent individuals, who are currently enrolled in treatment, and non-dependent individuals from the community. The non-dependent group was subdivided into those individuals who have professional contact with drug-dependent individuals (health professionals) and those who have no such professional contact. These 3 groups differ significantly in their beliefs where the control over the decision to take drugs is located, in the individual such as cravings [internal locus of control (LOC)] or in environmental circumstances such as peer pressure (external LOC). The groups also differed significantly on control beliefs regarding the recovery from addiction. Individuals who have an internal sense of control believe a successful recovery from addiction is determined by a person’s own efforts to stay abstinent (internal LOC), whereas those with an external sense of control hold the view that a successful recovery from addiction is controlled by external factors such as treatment or support from friends and family.

DISCUSSION

The DR-LOC is a new instrument for the assessment of subjective control beliefs in a drug-related context. The questionnaire is short, consisting of 2 scales measuring individuals’ perceptions of control regarding (i) the decision to take drugs; and (ii) the attainment of addiction recovery. In this initial study, we have shown that self-reported drug-related control beliefs differ significantly depending on prior experience with drug addiction, and this variation in control beliefs was not seen on the generalized LOC measure. This is an important first step in the validation of this new instrument; however, further clinical validation is needed to demonstrate its ability to accurately score individuals and to distinguish among clinical groups of patients (eg, in treatment versus non-treatment seeking). These initial validation results suggest that the DR-LOC has greater predictive validity for drug-taking behaviors than the Rotter’s I-E scale, justifying the development of a drug-taking–specific adaptation of the Rotter’s I-E scale.

Personal or Professional Experiences With Addiction Modulate Drug-related Control Beliefs

Drug addiction is associated with significant experiences in losing control, but these experiences are not captured by generalized control beliefs, which may be the reason why the Rotter’s I-E scale does not show discriminative validity between drug-dependent and non-dependent individuals.33–35 The present study provides preliminary evidence that both professional and personal experiences with drug addiction affect how a person perceives control in a drug-related context. Our data show that drug-dependent individuals have a much more internal sense of control in terms of addiction recovery than non-dependent individuals or people with professional experiences of addiction. It is, however, of note that all our drug-dependent volunteers were currently enrolled in a drug treatment program and in previous studies generalized control beliefs have been shown to change during treatment, from a more external toward a more internal orientation.36–38 It is conceivable that their receipt of treatment affected drug users’ judgments about addiction recovery.

Our data also showed that professional experiences with drug users had an impact on their drug-related control beliefs. This observation concurs with findings from previous studies showing that health professionals’ attitudes toward patients with and without drug-taking histories differ notably.39–42 As shown in Figure 1, the health professionals in our study considered external factors as critical for treatment success, whereas the drug-dependent individuals attributed to themselves the control over their treatment progress. A significant discrepancy also emerged with regard to decisions to take drugs: health professionals attributed control over drug-taking to internal sources to a significantly greater degree than the drug users. These discrepancies between drug users and health professionals are striking, but may not be unusual. Previous studies comparing the views of drug users and their therapists on treatment progress and drug-taking habits also found significant discrepancies.43 Furthermore, these studies revealed that the drug users’ perceptions on these issues had greater predictive value for the therapeutic outcome than those provided by their therapists.43,44 The predictive value of the DR-LOC scores for treatment outcome has to be established by future studies, but it is conceivable that the DR-LOC could help improve the therapeutic alliance between drug users and their counselors by highlighting the discrepancies in their control beliefs.

The DR-LOC may be regarded as an equivalent to the DRIE scale for a drug-related context. From a conceptual point of view, this comparison holds, but the item structure in the DR-LOC is different. The DRIE scale, which assesses drink-related control beliefs, includes personalized statements (eg, “I feel completely helpless when it comes to drinking”; or “Once I start drinking I cannot stop”), which are not suitable for individuals who never drink alcohol or those who have given up drinking alcohol. For the DR-LOC, we deliberately avoided personalized statements but used general statements instead (eg, “There are people who feel completely helpless when it comes to resisting taking drugs”), allowing the assessment of control beliefs in individuals irrespective of personal drug-taking experiences. This item structure is a key strength of the DR-LOC and distinguishes it from other LOC measures that were previously used in drug users.24,26 Furthermore, the DR-LOC allows one to measure all types of drug-related control beliefs as opposed to beliefs related to just 1 particular drug (ie, alcohol) because loss of control is a hallmark of addictive behavior in general and not specific to the drug of dependence. Moreover, the DR-LOC scale published here is a questionnaire measure with the potential to investigate environmental factors on control beliefs in individuals from very different backgrounds including, non-dependent family members, prison staff, police officers, or school teachers.

Psychometric Properties of the DR-LOC Compared With Other Measures of LOC

Our data are in keeping with previous studies suggesting that control beliefs are a multidimensional rather than unidimensional construct.45–47 Internal reliability of Rotter’s I-E scale has been deemed as low, but adequate, ranging from 0.65 to 0.79,18,46,47 whereas Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales seem to vary between 0.58 and 0.70 in different populations.28 We acknowledge that the Cronbach’s alphas estimate of 0.62 for the DR-LOC scale was lower than for the average I-E scale, but the low internal consistent reliability estimate should not be considered as a rationale for discarding data.48 The standard error (SE) of measurement and the confidence intervals provide more information than reliability estimates alone,48 and both proved sufficiently low (accurate scores) in our sample to justify its use in research comparing groups (using means). It is also of note that the DR-LOC contains only 16 items compared with 23 items in the I-E scale; a fact that is important to consider when Cronbach’s alpha estimates are based on the total number of items. Future revisions of the DR-LOC scale may therefore involve increasing the total number of items on the scale.

Potential of the DR-LOC

Generalized LOC is thought to be one of the most widely studied psychological constructs.49 The extension of the concept to drug abuse may offer new opportunities for both research and clinical practice. Not only is the loss of control central to the clinical phenotype of addiction, there also is growing evidence that the context in which control is exerted is relevant to drug-dependent individuals. For example, recent research has shown that the brain systems underlying inhibitory cognitive control are not measurably impaired in drug users when challenged in a neutral context, however, these systems become compromised when the neutral stimuli are replaced with drug-related cues.7 Importantly, in alcohol dependence it has recently been shown that compromised cognitive control in an alcohol-related context can improve with cognitive training.50 These cognitive improvements were concomitant with changes in drink-related control beliefs (as assessed using the DRIE) in patients with alcohol dependence.50 Whether or not changes in DR-LOC beliefs are equally amenable to treatment is an important question for future clinical research to address. Preliminary evidence indicates that therapeutic interventions in psychiatric patients are more successful when generalized control beliefs are taken into account.51,52

For neuroscientific research investigating impairments in executive control, the DR-LOC could also prove useful as an adjunct measure to better understand the neural correlates of control in an addicted population. Preliminary evidence suggests that generalized control beliefs are related to cortisol regulation and hippocampal volume in healthy volunteers,53 systems that are known to be altered in addiction.54,55 It has further been hypothesized that individual differences in generalized control beliefs may be mediated by dopaminergic neurotransmission.56,57 In light of the pivotal role of dopamine in drug addiction,58 a link with control beliefs in a drug-related context may be likely.

Limitations and Conclusions

We have presented a brief novel scale with demonstrated validity in measuring drug-related control beliefs in both drug-dependent and non-dependent individuals. When developing the measure, the use of the first person in the wording of the questionnaire items was deliberately avoided in an effort to allow the instrument to assess control beliefs across a range of individuals. In relation to this, it is important to note that we demonstrate that the DR-LOC has good discriminative value in differentiating the control beliefs of individuals with different prior experiences of drug addiction. The weakness of the DR-LOC is the relatively low internal consistency of the addiction recovery scale, despite the good factor loadings of items. However, this issue could be addressed in future studies using a revised DR-LOC scale.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their contributions to this study and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) for their dedicated support with data collection. Special thanks therefore go to Rachel Everett, Harriet McGrath, Muireann McSwiney, Jenny Lacey, Lauren Wright, Lucy Wigg, Lorna Jacobs, Mariam Errington, Naomi Bateman, Gabriel Abotsie, Regina Barreto, Zoe Given-Wilson, Kathryn Betts, Adrian Jackson, and Angela Browne. The authors also thank Paula Cruise for advice on questionnaire design, Anna Brown for statistical advice, and James Wason for comments on the final draft.

This work was funded by an MRC research grant and conducted within the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute, (supported by a joint award from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, www.addictiondisorders.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed, Text Revision American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward- related stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garavan H, Hester R. The role of cognitive control in cocaine dependence. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17:337–345. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillmore MT, Rush CR. Impaired inhibitory control of behavior in chronic cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monterosso JR, Aron AR, Cordova X, et al. Deficits in response inhibition associated with chronic methamphetamine abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ersche KD, Bullmore ET, Craig KJ, et al. Influence of compulsivity of drug abuse on dopaminergic modulation of attentional bias in stimulant dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:632–644. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marissen MAE, Franken IHA, Waters AJ, et al. Attentional bias predicts heroin relapse following treatment. Addiction. 2006;101:1306–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter KM, Schreiber E, Church S, et al. Drug stroop performance: relationships with primary substance of use and treatment outcome in a drug-dependent outpatient sample. Addic Behav. 2006;31:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ersche KD, Clark L, London M, et al. Profile of executive and memory function associated with amphetamine and opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1036–1047. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verdejo-Garcia A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, et al. Executive dysfunction in substance dependent individuals during drug use and abstinence: an examination of the behavioral, cognitive and emotional correlates of addiction. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:405–415. doi: 10.1017/s1355617706060486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aharonovich E, Nunes E, Hasin D. Cognitive impairment, retention and abstinence among cocaine abusers in cognitive-behavioral treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:207–211. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00092-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, et al. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teichner G, Horner MD, Harvey RT. Neuropsychological predictors of the attainment of treatment objectives in substance abuse patients. Int J Neurosci. 2001;106:253–263. doi: 10.3109/00207450109149753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein RZ, Craig AD, Bechara A, et al. The neurocircuitry of impaired insight in drug addiction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdejo-Garcia A, Perez-Garcia M. Substance abusers’ self-awareness of the neurobehavioral consequences of addiction. Psychiatry Res. 2008;158:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy PN, Bentall RP. Motivation to withdraw from Heroin—a factor-analytic study. Br J Addict. 1992;87:245–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallston KA, Wallston BS, Devellis R. Development of multidimensional health locus of control (Mhlc) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6:160–170. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spector PE. Development of the work locus of control scale. J Occup Psychol. 1988;61:335–340. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan DM, Oleary MR. Drinking-related locus of control scale - reliability, factor structure and validity. J Stud Alcohol. 1978;39:759–784. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1978.39.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huckstadt A. Locus of control among alcoholics, recovering alcoholics, and non-alcoholics. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10:23–28. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbott MW. Locus of control and treatment outcome in alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1984;45:46–52. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall EA. Feelings about drug use: drug-related locus of control. Criminal Justice Research Group, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; [Accessed April 16, 2010]. 2001. Available at: http://www.uclaisap.org/CJS/assets/docs/DRLOC_scale_instrumentation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann DJ. Replication and extension analyzing the factor structure of locus of control scales for substance-abusing behaviors. Psychol Rep. 1999;84:277–287. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald LM, Walker GC, Krajewski KJ, et al. General and specific locus of control in cocaine abusers. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:179–190. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coombs WN, Schroeder HE. Generalized locus of control: an analysis of factor analytic data. Personal Individ Diff. 1988;9:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherlin A, Bourque LB. Dimensionality and reliability of Rotter I-E scale. Sociometry. 1974;37:565–582. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical Analysis With Latent Variables. Version 6.1 Los Angeles; CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimovski M, Muraki E, Mislevy R, et al. BILOG-MG. Version 3.0.2776.1 Scientific Software Inernational; Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan RL. Manual for mGENOVA. Version 2.1 University of Iowa, Iowa Testing Programs; Iowa City, IA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth BM, Leukefeld C, Falck R, et al. Correlates of rural methamphetamine and cocaine users: results from a multistate community study. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:493–501. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty O, Matthews G. Personality characteristics of opiate addicts. Personal Individ Diff. 1988;9:171–172. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platt JJ. “Addiction proneness” and personality in heroin addicts. J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84:303–306. doi: 10.1037/h0076727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell JM, Tavares VC, Fields HL, et al. Endogenous opioid blockade and impulsive responding in alcoholics and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:439–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lennings CJ. Changes in responses of heroin-addicts on the locus of control scale in a therapeutic-community—Odyssey House. Aust Psychol. 1980;15:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Figurelli GA, Hartman BW, Kowalski FX. Assessment of change in scores on personal control orientation and use of drugs and alcohol of adolescents who participate in a cognitively oriented pretreatment intervention. Psychol Rep. 1994;75:939–944. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.2.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Leon G, Skodol A, Rosenthal MS. Phoenix house: changes in psychopathological signs of resident drug addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:131–135. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750310103017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard MO, Chung SS. Nurses’ attitudes toward substance misusers. II. Experiments and studies comparing nurses to other groups. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:503–532. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moodleykunnie T. Attitudes and perceptions of health-professionals toward substance use disorders and substance-dependent individuals. Int J Addict. 1988;23:469–475. doi: 10.3109/10826088809039212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson H, Maclaren W, Kerr S. Staff attitudes towards working with drug users: development of the Drug Problems Perceptions Questionnaire. Addiction. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knox WJ. Attitudes of psychologists toward druga-busers. J Clin Psychol. 1976;32:179–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197601)32:1<179::aid-jclp2270320145>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walton MA, Blow FC, Booth BM. A comparison of substance abuse patients’ and counselors’ perceptions of relapse risk: relationship to actual relapse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barber JP, Luborsky L, Crits-Christoph P, et al. Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome in treatment of cocaine dependence. Psychother Res. 1999;9:54–73. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parkes KR. Dimesionality of Rotter’s locus of control scale: an application of the ‘very simple structure’ technique. Personal Individ Diff. 1985;6:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harper H, Oei TPS, Mendalgio S, et al. Dimensionality, validity, and utility of the I-E scale with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 1990;4:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lange RV, Tiggemann M. Dimensionality and reliability of the Rotter I-E locus of control scale. J Personal Assess. 1981;45:398. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4504_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onwuegbuzie AJ, Daniel LG. A framework for reporting and interpreting internal consistency reliability estimates. Meas Eval Counsel Dev. 2002;35:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judge TA, Erez A, Bono JE, et al. Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83:693–710. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fadardi JS, Cox WM. Reversing the sequence: reducing alcohol consumption by overcoming alcohol attentional bias. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abramowitz CV, Abramowitz SI, Roback HB, et al. Differential effectiveness of directive and nondirective group therapies as a function of client internal-external control. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:849–853. doi: 10.1037/h0037572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snowden LR. Personality tailored covert sensitization of heroin abuse. Addict Behav. 1978;3:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pruessner JC, Baldwin MW, Dedovic K, et al. Self-esteem, locus of control, hippocampal volume, and cortisol regulation in young and old adulthood. NeuroImage. 2005;28:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neuro-circuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1442–1444. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nestler EJ. Common molecular and cellular substrates of addiction and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:637–647. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Brabander B, Declerck CH. A possible role of central dopamine metabolism associated with individual differences in locus of control. Personal Individ Diff. 2004;37:735–750. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Declerck CH, Boone C, De Brabander B. On feeling in control: a biological theory for individual differences in control perception. Brain Cogn. 2006;62:143–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, et al. Imaging dopamine’s role in drug abuse and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

a. Everybody has a choice as to whether they take drugs or not; what other people say or do has nothing to do with it.

a. Everybody has a choice as to whether they take drugs or not; what other people say or do has nothing to do with it. b. There is often a lot of pressure from peers to join in and use drugs.

b. There is often a lot of pressure from peers to join in and use drugs. a. It is difficult to resist drinking at a party where everybody is enjoying the booze.

a. It is difficult to resist drinking at a party where everybody is enjoying the booze. b. There should be no problems resisting temptations to drink on a night out if somebody has made up their mind beforehand that they don’t want to drink.

b. There should be no problems resisting temptations to drink on a night out if somebody has made up their mind beforehand that they don’t want to drink. a. Those who are successful in getting off drugs are often the lucky ones.

a. Those who are successful in getting off drugs are often the lucky ones. b. Getting off drugs depends upon lots of effort and hard work; luck has nothing to do with it.

b. Getting off drugs depends upon lots of effort and hard work; luck has nothing to do with it. a. For people who are addicted to drugs, it is impossible to stop taking drugs for good.

a. For people who are addicted to drugs, it is impossible to stop taking drugs for good. b. By taking an active part in a treatment program, it is possible to learn to control the use of drugs.

b. By taking an active part in a treatment program, it is possible to learn to control the use of drugs. a. Drugs bring out the bad side of people, making themdo things that they later regret.

a. Drugs bring out the bad side of people, making themdo things that they later regret. b. People who have become addicted to drugs have to take responsibility for their drug problems.

b. People who have become addicted to drugs have to take responsibility for their drug problems. a. There is no such thing as an irresistible temptation to take drugs.

a. There is no such thing as an irresistible temptation to take drugs. b. There are people who experience strong irresistible urges to take drugs that they cannot control.

b. There are people who experience strong irresistible urges to take drugs that they cannot control. a. Only when people come to terms with the long-term effects the drugs have on their lives, are they able to change their behaviour and give up drugs for good.

a. Only when people come to terms with the long-term effects the drugs have on their lives, are they able to change their behaviour and give up drugs for good. b. Drugs are so powerful; just knowing that they are around undermines all good intentions of giving up.

b. Drugs are so powerful; just knowing that they are around undermines all good intentions of giving up. a. The idea that people are driven to take drugs because of peer pressure is nonsense.

a. The idea that people are driven to take drugs because of peer pressure is nonsense. b. People are unaware of their friends’ influence when taking drugs.

b. People are unaware of their friends’ influence when taking drugs. a. Feelings of helplessness and anxiety drive people to drink or to take drugs.

a. Feelings of helplessness and anxiety drive people to drink or to take drugs. b. The idea that people use drugs or drink alcohol to cope with feelings of anxiety is just an excuse for their behaviour.

b. The idea that people use drugs or drink alcohol to cope with feelings of anxiety is just an excuse for their behaviour. a. There isn’t such a thing as an addictive personality.

a. There isn’t such a thing as an addictive personality. b. Not getting involved in drugs mainly depends on things going right for you.

b. Not getting involved in drugs mainly depends on things going right for you. a. For people who have known drugs for all their lives, it is almost impossible to break away because they cannot compare drugs to anything else.

a. For people who have known drugs for all their lives, it is almost impossible to break away because they cannot compare drugs to anything else. b. There is a direct connection between how hard people try and how successful they are in getting off drugs.

b. There is a direct connection between how hard people try and how successful they are in getting off drugs. a. Everybody can pull themselves together and fight the urge to drink or to take drugs.

a. Everybody can pull themselves together and fight the urge to drink or to take drugs. b. There are people who feel completely helplesswhen it comes to resisting taking drugs.

b. There are people who feel completely helplesswhen it comes to resisting taking drugs. a. Anybody can become addicted to drugs when they get off the straight and narrow.

a. Anybody can become addicted to drugs when they get off the straight and narrow. b. Drug use is an excuse for not doing the things that you are supposed to do.

b. Drug use is an excuse for not doing the things that you are supposed to do. a. Addiction is for life: once contracted, it will never go away, no matter what you do.

a. Addiction is for life: once contracted, it will never go away, no matter what you do. b. Successful recovery from addiction is possible but it is hard work.

b. Successful recovery from addiction is possible but it is hard work. a. If people want something badly enough, they can make it happen; they can even beat addiction.

a. If people want something badly enough, they can make it happen; they can even beat addiction. b. People with addictive personalities will always be addicted to something; if they stop using drugs they start using something else.

b. People with addictive personalities will always be addicted to something; if they stop using drugs they start using something else. a. No one is in control of what they do when drunk or drugged up.

a. No one is in control of what they do when drunk or drugged up. b. With enough effort, everybody is able to control what they do.

b. With enough effort, everybody is able to control what they do.