Abstract

BACKGROUND

Self-management (SM) is proposed as the standard of care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but details of the process and training required to deliver effective SM are not widely available. In addition, recent data suggest that patient engagement and motivation are critical ingredients for effective self-management. This manuscript carefully describes a self-management intervention using Motivational Interviewing skills, aimed to increase engagement and commitment in severe COPD patients.

METHODS

The intervention was developed and pilot tested for fidelity to protocol, for patient and interventionist feedback (qualitative) and effect on quality of life. Engagement between patient and interventionists was measured by the Working Alliance Inventory. The intervention was refined based in the results of the pilot study and delivered in the active arm of a prospective randomized study.

RESULTS

The pilot study suggested improvements in quality of life, fidelity to theory and patient acceptability. The refined self-management intervention was delivered 540 times in the active arm of a randomized study. We observed a retention rate of 86% (patients missing or not available for only 14% the scheduled encounters).

CONCLUSIONS

A self-management intervention, that includes motivational interviewing as the way if guiding patient into behavior change, is feasible in severe COPD and may increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management. This provides a very detailed description of the SM process for (the specifics of training and delivering the intervention) that facilitates replicability in other settings and could be translated to cardiac rehabilitation.

Key words or phrases: COPD, self-management, behavior change, physical activity, motivational interviewing

Patient self-management has been proposed as a critical part of the management of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),1 given the positive effect on hospitalization,2 health status,3 or both.4 These results fueled a significant interest in COPD self-management in recent years. However, a recent report from an expert panel concluded that publications on COPD self-management interventions lack detailed description of intervention content and process.5 Such a description is particularly relevant given that not every self-management intervention has shown effectiveness.6–9 Patient motivation for engagement in self-management (behavior change), is an aspect that has been recently shown to adversely impact the effectiveness of a self-management intervention on COPD patient outcomes.7 Consequently, Motivational Interviewing, a method for enhancing personal commitment to change, appears to be a complimentary approach to self-management education. Motivational Interviewing is an evidence-supported collaborative, person centered form of guidance to elicit and strengthen motivation for change.10,11

We aimed to develop and test an intervention that focused on patient engagement for behavior change in important aspects of the daily life in severe COPD patients that can have impact on their perception of health and hospitalizations12 and that could be integrated with pulmonary rehabilitation. This manuscript describes the development, training required, pilot testing, and delivery of the motivational interviewing-based, self-management intervention, with results addressing intervention feasibility, patient acceptability, retention, and opinion of the intervention and relationship with interventionist.

METHODS

This intervention was developed for a randomized clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health (USA). The overarching goal of the study is to reduce further COPD-related hospitalizations in COPD patients that have been recently hospitalized. It is hospitalizations that drive the high cost of COPD and other chronic disease care.13

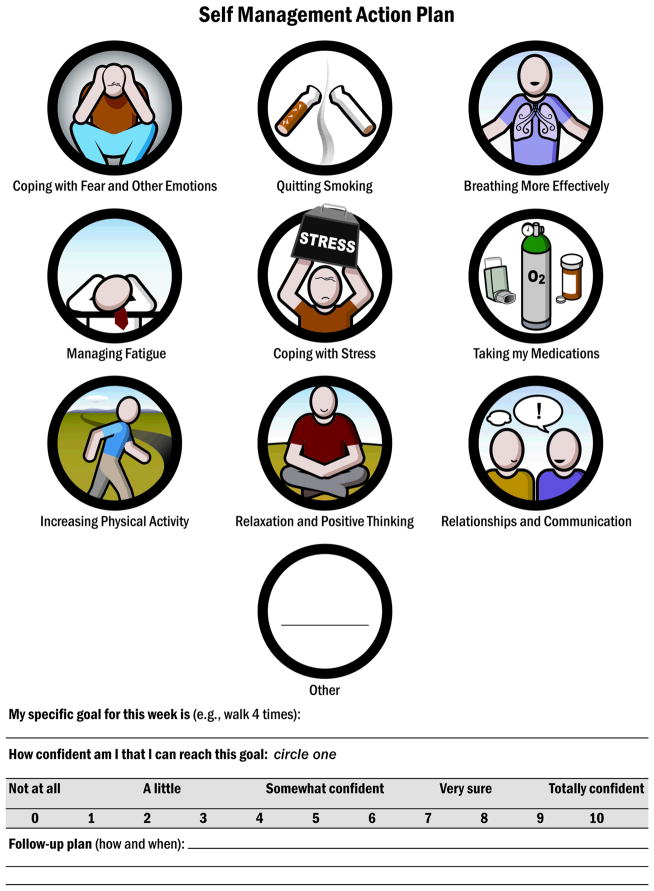

The study intervention merges both self-management education14 and Motivational Interviewing.15 The latter with the intention of facilitating the resolution of ambivalence, fostering engagement in self-management, and encouraging behavior change. To ensure that the intervention protocol matched the spirit of these approaches, recognized experts in self-management education, and in Motivational Interviewing, were active consultants during intervention design and training. An intervention protocol or “roadmap” (see Tables 1–3 for condensed content from the intervention roadmap) guided intervention training and delivery. However, the roadmap is not meant to be used as a strictly observed algorithm or script, instead it is a guide for the interventionist, who is empowered to use it with flexibility. A recent meta-analysis of motivational interviewing interventions revealed that if a protocol was too rigid, it was associated with poorer outcomes.16 Core intervention content includes collaborative goal setting grounded in a COPD self-management action plan. The key action plan domains (Figure 1) are based on previously studied self-management domains17 and prior findings from our previous work with COPD patients.12 We were particularly careful to keep the written action plan for antibiotics and steroids (called emergency plan in this manuscript) that has shown to be a necessary (but not sufficient) component for preventing a rehospitalization in COPD.4

Table 1.

Brief Summary of Intervention Content for Session 1

| Content Outline | Additional Considerations for Interventionist |

|---|---|

| Welcome, introduce program, and set agenda for session | |

| Elicit participant thoughts and feelings about health and health behavior eg, What are you doing for your health now? What are your thoughts about your recent hospitalization?) |

|

Introduce self-management tools briefly

|

|

| Personalized discussion of Emergency Plan |

|

| Breathing training |

|

| Physical activity daily practice |

|

| Elicit participant thoughts and feelings about the session |

|

| Discuss the guidelines and expectations for the home visit. | |

| Provide brief overview of session 2 and close session |

Table 3.

Brief Summary of Intervention Content for Followup Sessions

| Content Outline | Additional Considerations for Interventionist |

|---|---|

| Greeting, set agenda for session | |

| Review progress since previous session |

|

| Reinforce all steps toward change, discuss lessons learned, and collaborate in problem-solving around barriers |

|

| Collaborate with new, revised, or continued Self-Management Action Plan |

|

| Elicit participant thoughts and feelings about the session |

|

| Briefly describe what patient can expect in next session and close |

Abbreviations: O.A.R.S., open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries; E-P-E, Elicit-Provide-Elicit.

Figure 1.

Self-Management Action Plan

Intervention Content

In the first of 8 weekly sessions (Table 1), participants learn key behaviors for COPD management

First key behavior - the use of an Emergency Plan (ie, self-administration of antibiotic and prednisone in the context of an exacerbation), which has been previously associated with reduction in health care utilization.2,4

Second key behavior - a breathing awareness practice (slow, mindful, pursed lips breathing) including demonstration and rehearsal with patient.

Third key behavior - consisted on a daily practice, a time carved out in the day to just dedicate to embrace simple physical exercises (3 or 4 upper extremity exercises and lower extremity movements that could be just walking or using a portable, inexpensive [less $80] stationary cycle ergometer provided as part of this study).

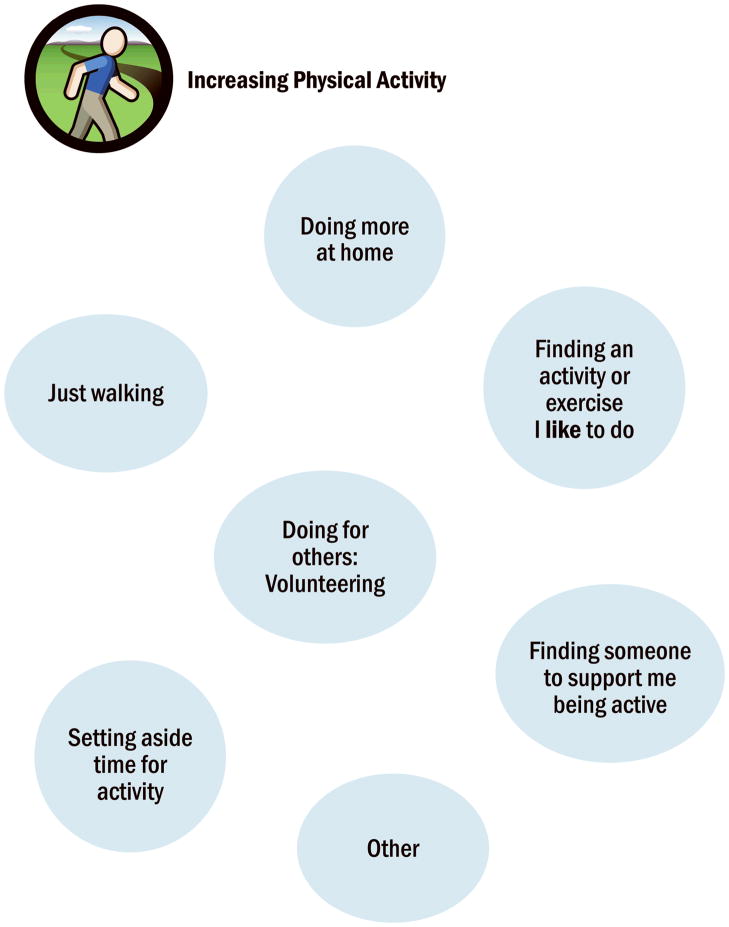

The following 7 sessions involve self-management action planning, in which the patients selects a self-management domain (Figure 1) of interest to them and collaborates with the interventionist in identifying specific strategies that can be used to make progress in that area (Tables 2, 3). Action planning continues by collaboratively setting a realistic goal that is completed in the next several days. The interventionist continuously elicits ideas from the patient and helps connect the discussion to what is personally relevant to the patient. Patients are asked to rate their self-efficacy (confidence) to accomplish their goals by using a self-efficacy scale in their action plan (scale: 0 (no confidence) to 10 (maximal confidence, Figure 1). At times, the patient is unable to identify a self-management strategy in the action planning process. The interventionist then provides a self-management worksheet that shows a “menu of options” (Figure 2) of selected self-management strategies for that behavioral domain as reported in other motivational interviewing-health coaching guides,18 At each session, the patient describes experiences with daily practice of physical activity, self-management goals, and any use of the Emergency Plan.

Table 2.

Brief Summary of Intervention Content for Session 2

| Content Outline | Additional Considerations for Interventionist |

|---|---|

| Greeting, set agenda for session | |

| Elicit participant experience and opinions about the self-management goals from session 1 |

|

| Individualized, collaborative conversation about physical activity recommendations |

|

| Describe and then discuss “self-management” |

|

| Review the Self-Management Action Plan (Figure 1) |

|

| Collaborate in creating action plan on the Self-Management Action Plan form (most often physical activity at session 2) |

|

| Elicit participant thoughts and feelings about the session |

|

| Briefly describe what patient can expect in session 3 and close session |

Abbreviations: O.A.R.S., open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries; E-P-E, Elicit-Provide-Elicit.

Figure 2.

Sample Bubble sheet for increasing physical activity

Interventionist Training

The intervention was designed for integration within the standard medical care of COPD patients, thus, we purposefully designed it to be delivered by pulmonary rehabilitation professionals, respiratory therapists, or nurses versus psychologists or trained health coaches. Both interventionists (1 registered nurse, 1 respiratory therapist) received the same training, which included 1) face-to-face training on theory and strategies associated with self-management education and motivational interviewing in general (6 hours); 2) reading materials that detailed skills and strategies associated with self-management education19 and motivational interviewing;18 3) role play-based experiential learning of intervention strategies with patient vignettes (5 hours); and 4) recorded intervention sessions were reviewed and interventionists were provided tailored training to discuss strengths, missed opportunities for use of intervention strategies, and any deviations from the intervention protocol (10 hours over 6 months). Training sessions that incorporate feedback from coded sessions increase skill retention.15 All training sessions were audio or video recorded for future review to minimize drift from intervention protocol.

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment fidelity strategies were considered in all stages of intervention development, interventionist training and intervention delivery. These strategies,20 which are used to monitor and improve the reliability and validity of behavioral trials, were used in the present study to inform the methods and monitoring of study design, interventionist training, and delivery of the intervention. Table 4 provides details of treatment fidelity strategies included in the development and implementation of the COPD self-management intervention. The 2 study interventionists were evaluated against defined performance criteria, which included a score of 3 or higher on the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) 3.1.1 global scale scores.21

Table 4.

Treatment Fidelity Strategies Used in Design of Study, Training Interventionists, and Intervention Delivery

| Goal | Strategies Used |

|---|---|

| Study design: Ensure the same treatment dose within condition |

|

| Training interventionists: Standardize training |

|

| Training interventionists: Ensure provider skill acquisition |

|

| Training interventionists: Standardize training: Minimize drift in provider skills |

|

| Training interventionists: Accommodate provider differences |

|

| Intervention delivery: Standardize delivery and ensure adherence to intervention protocol |

|

Pilot Testing of Intervention

A pilot study was conducted to collect data regarding interventionist fidelity to treatment during intervention delivery, feasibility of the intervention based on our ability to recruit and retain participants, and patient acceptability of the intervention based on qualitative interviews following intervention participation.

Pilot Study Participants and Procedure

Eleven patients hospitalized for a COPD exacerbation in 1 of the participating hospitals (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (n=6) and Health Partners Regions Hospital, Minneapolis, MN (n=5) participated in the IRB approved pilot study. The intervention included weekly in-person sessions over 8 weeks. Each session included self-management coaching (60 minutes first session, 30 minutes subsequent session) and 60 minutes of pulmonary rehabilitation. All encounters were audio recorded for fidelity analysis. Measures included the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ),22 a measure of quality of life, and the (modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) 0–4 scale),23 a measure of dyspnea and spirometry, and an individual interview-eliciting opinions of the intervention.

RESULTS

Patients attended all scheduled sessions of the Pilot Study. The mean (SD) age was 70 (7) years, with a mean percent of predicted forced expiratory volume in the first second of exhalation (FEV1%) of 40 (20) indicating mostly severe obstruction of the airway, and a mean modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score of 2.5 (1) indicating clinically meaningful shortness of breath.

The CRQ results showed a positive trend in all domains and a statistically significant change in the domain of emotions: CRQ Dyspnea (baseline / postintervention): 4.0 (1.48)/ 4.1 (1.33); CRQ Fatigue: 3.4 (1.11)/ 3.6 (0.87); CRQ Emotional: 4.0 (1.32)/ 4.5 (1.01) P=.04; and CRQ Mastery: 4.0 (1.63)/ 4.4 (1.17). Responder analysis indicated that 7 of the 11 patients tested improved in at least 1 domain of the CRQ by the minimal clinical important difference of 0.5.

Qualitative Analysis of the Pilot Study

All 11 participants were interviewed by a study investigator who did not deliver the intervention. These interviews were conducted by telephone and were guided by a semistructured interview guide, which included open-ended questions and rating scales. These questions assessed satisfaction with program content and delivery, perceived benefits of the program and behavior changes resulting from the program. Scaling questions revealed that participants viewed the program as very practical (mean rating 8.19 on a 10 point scale where 10=most practical), reported themselves very likely to use their Emergency Plan (antibiotic and prednisone) when short of breath (mean rating 9.72, 10=very likely), and highly likely to use slow, pursed lip breathing (mean rating 9.72, 10=very likely). The majority of participants (90%) rated the overall program as “very good” or “excellent”. Participants were satisfied with the length of sessions, but several (18%) recommended increasing the number of sessions.

Data from interview questions was analyzed independently by 2 study investigators using methods of content analysis.33 Interview data was overwhelmingly positive, and participant responses revealed several predominant themes: the intervention and the accompanying workbook34 provided new knowledge about COPD and self-management of COPD, the intervention helped participants increase their physical activity and breathing, and participants valued the relationship with and support from the interventionist.

Intervention Refinement Following Pilot Study

Based on feedback from patients in the pilot study and patient barriers to treatment identified in the literature, the program length and location was refined. The intervention was increased from 8 sessions to 12 sessions based on patient feed-back in the qualitative interview. Due to transportation barriers,35 the intervention was refined to include an initial in-person visit either at the medical center or in the patient home, and the remainder of sessions could be completed over the telephone in order to maximize to availability of the intervention to patients.

Alliance Between Patient and Interventionist

In the delivery of the refined intervention, we added a tool, the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-SR) that, measures a) agreement between patient and provider on the self-management tasks, b) agreement on the goals of self-management, and (c) development of an affective bond between the interventionist and the patient.36 Based on previous research,37 we hypothesize that higher working alliance will be associated with better patient outcomes.38,39

Working alliance constructs have been shown to influence medical outcomes, including: communication,24 agreement on treatment,25 and treatment adherence.26 The working alliance is a construct that partially captures communication and relationship factors that have an impact on healing in certain contexts.27 Many healthcare providers create a sense of collaboration and mutual respect while working with their patients which influences treatment outcomes.24–26 This study expands the use of the working alliance construct as a possible outcome predictor for physical therapists working with chronic pain patients.

Ely et al23 reported a reliability estimate for the short version of the WAI as 0.88. Catty et al, in reviewing alliance measures, described the WAI as having “a clear conceptual basis, with evidence of face, content, and construct validity”28 p246 and that the WAI questions are based on a sound trans theoretical model of working alliance.28 Responses are given in the form of a 5 item Likert Scale (with endorsements from completely disagree to completely agree). The WAI produces a continuous measurement of the working alliance that ranges from 12–60 with higher scores indicating better alliances.

Results After the Delivery of the Refined Intervention

The refined intervention was delivered in 544 encounters in 44 severe COPD patients randomized to the treatment arm of the above referenced study. Completion of scheduled sessions was high (83.6%), indicating feasibility of the intervention and patient acceptability and retention. The mean time duration of each intervention session was 29±10 minutes. Goals were set in 83% of the intervention sessions and the mean patient-reported confidence (self-efficacy) score to attain the goal was 8.1±1) on a scale of 0 (no confidence) to 10 (maximal confidence) (see figure 1 for confidence rule in the self-management action plan).

Goals were focused on activity in 41% of the encounters, use of medication (including the use of an emergency plan for exacerbations) - 12 %, dealing with emotions and stress - 10%, learning ways to breathe more effectively - 10%, quitting smoking - 4%, and communications -3%. The remainders of goals were more specific to individual patients that could not be included in the selected domains. In 60% of the encounters, patients rated their awareness of their goal for the week as “very often” or “all the time”. Interventionists rated the patient progress toward the goal as “very good” or “excellent” in 58% of the encounters, “good” progress in 16 %, “fair” progress in 14%, and “poor” progress on 12%.

WAI-SR results revealed positive perceptions of the patient/interventionist relationship. Patients reported that: 1) they frequently agreed with the interventionist about strategies to improve the patient situation (“very often” or “always” in 88.5% the interventions); 2) they had confidence that the interventionist could help them (“very often” or “always” in 84% the interventions); 3) they worked towards mutually agreed upon goals (“very often” or “always” in 84.6% the interventions) and agreed on what was important to work on (“very often” or “always” in 84.6% the interventions); and 4) the way they were working on their problems was correct (“very often” or “always” in 100% the interventions).

DISCUSSION

This manuscript confirms that a COPD self-management intervention that uses motivational interviewing tools is feasible. We can report with confidence after pilot testing, refinement, and final delivery in the clinical setting, that the intervention produced no harm, increased patient satisfaction, and merges self-management14 and Motivational Interviewing.14 The personalized approach was clearly recognized and valued by the patients in the qualitative analysis, and expressed in the Working Alliance Inventory, indicating that this approach fosters real collaboration, which is a desired outcome in every self-management intervention. We believe that the observed intervention retention (86%) is an indicator of patient acceptability.

Importantly this intervention keeps the component that seems to be important for positively affecting health care utilization, that is, the use a written emergency action plan while adding a component aimed to patient engagement (Motivational Interviewing) what seem to be critical factor for effectiveness.8,11 The qualitative study indicated study patients felt very likely that they would use their Emergency Plan (behavior modification) in the context of a impending flare-up of COPD (mean rating 9.72, 10=very likely).

Study limitations

While our results thus far indicate feasibility, patient acceptance, and perceived positive impact, it is not yet clear that the intervention will effectively reduce hospitalizations, as that question is being addressed in an active clinical trial. Training for this intervention requires access to a professional with expertise in motivational interviewing, self-management education, and fidelity monitoring. Some medical centers may need to access external consultants and health coach training programs for interventionist training and fidelity to treatment monitoring.

CONCLUSION AND PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

This intervention honored a set of principles that we believe are key for participatory medicine in rehabilitation: eliciting motivation and patient engagement by avoiding a prescriptive behavior and honoring patient autonomy. In doing so, we have discovered that behavior change is needed not only in patients but also in health care providers, in using proper communication to create conditions which foster self-management and a spirit of collaboration. Our preliminary results support a feasible and acceptable intervention that can be used in clinics, pulmonary rehabilitation, and likely, cardiac rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work has been funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Grant 5R01HL094680-03 (PI: R Benzo) Multicomponent Intervention to Decrease COPD-Related Hospitalizations.

References

- 1.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Self-management abilities, physical health and depressive symptoms among patients with cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A disease-specific self-management intervention. Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163:585–591. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trappenburg JC, Monninkhof EM, Bourbeau J, et al. Effect of an action plan with ongoing support by a case manager on exacerbation-related outcome in patients with copd: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2011;66:977–984. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:890–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1579OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effing TW, Bourbeau J, Vercoulen J, et al. Self-management programmes for copd: Moving forward. Chronic respiratory disease. 2012;9:27–35. doi: 10.1177/1479972311433574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benzo R. Collaborative self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Learning ways to promote patient motivation and behavioral change. Chronic respiratory disease. 2012;9:257–258. doi: 10.1177/1479972312458683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucknall CE, Miller G, Lloyd SM, et al. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSUST) for patients with moderate to severe copd: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walters JA, Turnock AC, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Action plans with limited patient education only for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD005074. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005074.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:673–683. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. BMJ. 2010;340:c1900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benzo RP, Chang CC, Farrell MH, et al. Physical activity, health status and risk of hospitalization in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80:10–18. doi: 10.1159/000296504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perera PN, Armstrong EP, Sherrill DL, Skrepnek GH. Acute exacerbations of copd in the united states: Inpatient burden and predictors of costs and mortality. COPD. 2012;9:131–141. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.650239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010;78:868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39:1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosengren D. Building motivational interviewing skills. Guilford Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama. 2002;288:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the nih behavior change consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JE, Singh SJ, Sewell L, Guyatt GH, Morgan MD. Development of a self-reported chronic respiratory questionnaire (crq-sr) Thorax. 2001;56:954–959. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.12.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ely B, Alexander LB, Reed M. The working alliance in pediatric chronic disease management: A pilot study of instrument reliability and feasibility. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Kominski GF, Yu F, Chiang LM. A randomized trial of chiropractic and medical care for patients with low back pain: Eighteen-month follow-up outcomes from the ucla low back pain study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:611–621. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000202559.41193.b2. discussion 622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG, 3rd, Young G, Coster G, Arroll B. Physician-patient relationship and medication compliance: A primary care investigation. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:455–461. doi: 10.1370/afm.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulliam C, Gatchel RJ, Robinson RC. Challenges to early prevention and intervention: Personal experiences with adherence. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:114–120. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000;68:438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catty J, Winfield H, Clement S. The therapeutic relationship in secondary mental health care: A conceptual review of measures. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:238–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]