Abstract

Protein complex of the cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane formed by type 2 ryanodine receptor, junction, triadin, and calsequestrin is responsible for controlling SR calcium (Ca) release. Increased intracellular calcium (Cai) activates the electrogenic sodium–Ca exchanger current, which is known to be important in afterdepolarization and triggered activities (TAs). Using optical-mapping techniques, it is possible to simultaneously map membrane potential (Vm) and Cai transient in Langendorff-perfused rabbit ventricles to better define the mechanisms by which Vm and Cai interactions cause early afterdepolarizations (EADs). Phase 3 EAD is dependent on heterogeneously prolonged action potential duration (APD). Electrotonic currents that flow between a persistently depolarized region and its recovered neighbors underlies the mechanisms of phase 3 EADs and TAs. In contrast, “late phase-3 EAD” is induced by APD shortening, not APD prolongation. In failing ventricles, upregulation of apamin-sensitive Ca-activated potassium (K) channels (IKAS) causes APD shortening after fibrillation-defibrillation episodes. Shortened APD in the presence of large Cai transients generates late-phase 3 EADs and recurrent spontaneous ventricular fibrillation. The latter findings suggest that IKAS may be a novel antiarrhythmic targets in patients with heart failure and electrical storms.

Keywords: Triggered activity, After depolarization, Ventricular fibrillation, Calcium dynamics, Optical mapping

Introduction

Protein complex of the cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane formed by type 2 ryanodine receptor, junction, triadin, and calsequestrin is responsible for controlling SR calcium (Ca) release [25]. Increased intracellular Ca (Cai) activates the electrogenic sodium-Ca exchanger current (INCX), causing depolarization and triggered activities (TAs) [20]. Choi and Salama [7] pioneered methods to simultaneously map membrane potential (Vm) and Cai transient in Langendorff-perfused rabbit ventricles. We have adapted their methods to investigate the relationship between Cai transient and ventricular arrhythmogenesis.

Methods of Optical Mapping

All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Animals were anesthetized before any intervention. Most of our studies used New Zealand white rabbits. The hearts were removed while the rabbits were under general anesthesia and were immediately Langendorff-perfused with 37°C oxygenated Tyrode’s solution equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to maintain a pH of 7.40 ± 0.05. The coronary perfusion pressure was regulated and maintained at 70–80 cmH2O. The heart was then stained with Rhod-2 Am for Cai and RH237 for Vm. The hearts were illuminated with a laser (Verdi; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) at a wavelength of 532 nm. The fluorescence was filtered and acquired simultaneously with two complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor cameras (BrainVision, Tokyo, Japan) at 2 ms/frame and 100 × 100 pixels with spatial resolution of 0.35 × 0.35 mm2/pixel. We performed optical mapping of either epicardial or endocardial surface. The average fluorescence level (Ḟ) of an individual pixel was first calculated for the duration of recording. The ratio on each pixel was then calculated as (F − Ḟ)/Ḟ. The image data were spatiotemporally filtered with 3 × 3 × 3 averaging. To generate the ratio maps, shades of red were assigned to represent greater-than-average fluorescence (depolarization), and shades of blue were assigned to represent lower-than-average fluorescence (repolarization).

Types of Afterdepolarizations

Afterdepolarizations can be classified into early afterdepolarization (EAD), delayed afterdepolarization (DAD), and late-phase 3 EAD [6]. All three forms of afterdepolarizations are initiated by spontaneous depolarizations during phase 2, 3, or 4 of the action potential. We will focus the discussion on the mechanisms of phase 3 EAD and late-phase 3 EAD, which are two completely different phenomena. Table 1 lists the two different types of afterdepolarizations. More expanded discussion is given later in the text.

Table 1.

Phase 3 EAD versus Late-phase 3 EAD

| Phase 3 EAD | Late–phase 3 EAD |

|---|---|

| Associated with APD prolongation | Associated with APD shortening |

| Mostly induced by electrotonic current across steep APD gradient | Induced by INCX activation due to persistent Ca2+ increase in late phase 3 |

| May underlie the mechanisms of (1) drug-induced long QT and sudden death and (2) increased arrhythmia during heart failure and hypokalemia | May underlie the mechanisms of (1) immediate recurrence of AF after cardioversion and (2) electrical storm in patients with heart failure |

Phase 3 EADs and TA

Previous studies have shown that EADs are strongly associated with ventricular arrhythmias in long QT syndrome (LQTS). The mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis are thought to be due to either phase 2 or 3 EADs. It is generally accepted that phase 2 EADs result from the reactivation of L-type calcium current (ICa,L) and/or spontaneous Ca release from the SR [8, 12, 21]. The ionic mechanism of phase 3 EADs, however, is less clear. A review of literature showed that phase 3 EADs have usually been reported in intact tissue preparations, such as Purkinje fibers or ventricular muscle [2, 10, 11, 17, 19]. It is rarely observed in single cells. It is possible that most phase 3 EADs observed in tissues are not a genuine cellular-level phenomenon but instead are a consequence of “prolonged repolarization-dependent re-excitation” [3]. The latter phenomenon occurs because the dispersion of repolarization is enhanced in LQTS. A voltage gradient between long and short APD regions could create a “boundary” current that electrotonically depolarizes the short APD region as it tries to repolarize, generating TA. Maruyama et al. [14] tested this hypothesis by performing high-resolution optical mapping of Cai and membrane voltage (Vm) in a rabbit model of acquired LQTS, which was accompanied by computer simulations that reproduced the experimental observations. The experiments were performed in Langendorff-perfused normal rabbit hearts using simultaneous Cai- and Vm-mapping techniques. EADs and TAs were induced by bradycardia after endocardial cryoablation, a selective rapid delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) blocker E–4031 (0.5 μmol L−1; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO), and 50% decrease of extracellular potassium ([K+]0) and magnesium ([Mg2+]0) concentrations [8].

Exposure to 0.5 μmol L−1 E–4031 in combination with a 50% decrease in [K+]0 and [Mg2+]0 prolonged QT intervals and induced R-on-T ectopic beats in all hearts studied. Because the QT interval was prolonged, both APD dispersion and maximal voltage gradient (VG) during repolarization increased. The voltage gradient occurred because APD prolongation was spatially heterogeneous, causing “island”-like long APD regions to emerge (Fig. 1a), with a large VG at the boundary zone between the long and short APD regions. Phase 2 EADs and R-on-T ventricular ectopic beats were observed after decreasing [K+]0 and [Mg2+]0. Phase 2 EADs further enhanced heterogeneity of repolarization because they occurred exclusively in long APD regions. Phase 3 EADs became manifest after E–4031 infusion with low [K+]0 and [Mg2+]0 (Fig. 1b). BAPTA-AM, a Cai chelating agent, decreased the maximal amplitude of Cai transient and abolished phase 2 EADs, but phase 3 EADs persisted after BAPTA-AM loading in all hearts studied. These findings suggest that whereas phase 2 EADs are Cai-dependent, phase 3 EADs are not. Interestingly, the largest phase 3 EADs always occurred at the boundary between long and short APD regions. The EAD amplitude correlated with VG at the time of EAD onset at the site with the largest phase 3 EAD. Taken together, the findings suggest that electrotonic currents flowing from more positive Vm in long APD regions to shorter APD regions can cause phase 3 EADs at the boundary zone without there being any requirement for SR Ca release.

Fig 1.

Development of phase 2 and 3 EADs. a The spatial distribution of APDs and voltage gradients (VG) during repolarization is displayed in color-scaled maps. Optical APs at the maximal (filled squares) and minimal (unfilled squares) APD sites are shown with pECG. In addition to E–4031, decreasing [K+]0 and [Mg2+]0 greatly enhanced repolarization heterogeneity. Note that the appearance of the phase 2 EAD (filled circle) further increased the VGs and was associated with emergence of an R-on-T ventricular ectopic beat (asterisk). APD was not measurable in a blank area of the APD map where repolarization was interrupted by the ectopic beat. b With E–4031 alone, there was no phase 3 EAD. Phase 3 EAD (unfilled circles) and ectopic beats (asterisk) emerged after a decrease in [K+]0 and [Mg2+]0. Phase 3 EAD is discernable as the Vm difference between the resting Vm and the first deviation from the smooth contour during phase 3 repolarization. Reproduced from Maruyama et al. [13] with permission

Late Phase 3 EADs and Their Role in the Initiation of Cardiac Fibrillation

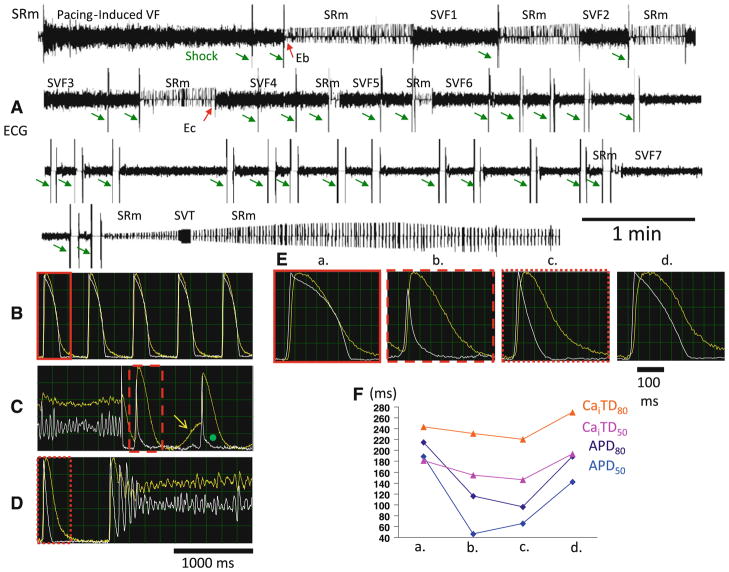

As listed in Table 1, “late-phase 3 EAD” and “phase 3 EAD” are different mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis. The term “late-phase 3 EAD” was coined by Burashnikov and Antzelevitch [4]. This mechanism of arrhythmogenesis may be responsible for immediate recurrence of atrial fibrillation (AF) after cardioversion, and may also be relevant to other types of cardiac arrhythmias [16, 18]. While trying to study the mechanisms of ventricular fibrillation (VF) in rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure, Ogawa et al. discovered that recurrent VF (electrical storm) occurred in some of the failing ventricles. Figure 2a shows a continuous pseudo-electrocardiogram (pECG) recording in a failing heart. The initial sinus rhythm was interrupted by pacing-induced VF, which was terminated by defibrillation shocks (green arrows) and followed by seven spontaneous VF (SVF) and one spontaneous ventricular tachycardia episodes in rapid succession. This sequence of events simulates the electrical storm seen in human patients. Figure 2b, c, d show the Vm recording (white line) and the Cai (yellow line) optical signals obtained during baseline sinus rhythm immediately after direct current termination of pacing-induced VF and spontaneous conversion of sinus rhythm to SVF4, respectively. There was spontaneous Cai increase in a second post-shock beat (shown in Fig. 2c; (yellow arrow). Although the Cai increase was associated with DAD, no VF was initiated. Afterward, the APD is abbreviated, but the Cai is large. Persistent increase of Cai beyond the end of the action potential created a late-phase 3 EAD (green dot). Figure 2d shows SVF4. The first beat of SVF occurred during late phase 3 of a short AP and when Cai was still increased, which is consistent with late-phase 3 EAD. Figure 2e shows single beats at four different time points during the experiment, including baseline, after fibrillation–defibrillation (Eb), immediately before SVF4 (Ec), and 15 min after SVF7. Figure 2f shows time-dependent changes of APD and intracellular calcium transient duration (CaiTD) after defibrillation, showing the transient nature of the APD shortening. Late-phase 3 EAD-induced after defibrillation, showing the transient nature of the APD shortening. Late-phase 3 EAD-induced triggered extrasystoles represent a new concept of arrhythmogenesis in which abbreviated repolarization permits normal SR Ca release to induce an EAD-mediated closely coupled triggered response, particularly under conditions permitting Cai loading. These EADs are distinguished by the fact that they interrupt the final phase of repolarization of the action potential (late phase 3). Compared with previously described DAD or Cai-dependent EAD, it is normal Ca-induced Ca release, not spontaneous SR Ca release, that is responsible for the generation of the EAD.

Fig 2.

VF storm in a failing heart. There were a total of seven episodes of SVF within 20 min after initial successful defibrillation in this rabbit heart. a Continuous recording of pECG. b Baseline Vm (white line) and Cai (yellow line) recordings. c, d Vm and Cai at termination and at onset of SVF, respectively. Yellow arrow points to post-shock spontaneous Ca increase, which was associated with DAD. Afterward, there was an abbreviated action potential and late-phase 3 EAD (green dot). The large persistent Cai increase may be responsible for the occurrence of the late-phase 3 EAD. Note the presence of short APD in the immediate post-shock period (c) and that the first ectopic beat initiating VF occurred from late phase 3 of the preceding action potential (d). The tracings in red boxes in b through d are also shown in (e), which highlights the Vm and Cai changes at different time points during the study. There was transient shortening of APD and, to the lesser extent, CaiTD after defibrillation. f Measurements of APD and CaiTD, depicting the transient nature of these changes. The time points “b” and “c” are marked as Eb and Ec, respectively, in a. The time points “a” and “d” are from baseline and 31 min after the last episode of SVF, respectively. Time point “d” is outside of the range and is not part of the figure. Modified from Ogawa et al. [15] with permission

Small-Conductance Ca-Activated Potassium Channel and Late-Phase 3 EAD

Late-phase 3 EAD occurs only in failing hearts and is associated with APD shortening. The mechanisms by which VF-defibrillation episodes are followed by APD shortening remain unclear. Because VF is associated with Cai accumulation, especially in failing ventricles [1, 13, 24], we hypothesized that apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels may be in part responsible for post-shock APD shortening. Apamin is a neurotoxin that selectively blocks SK channels [5, 26]. Previous studies in cardiac tissues showed that apamin-sensitive K+ current (IKAS) is abundantly present in cardiac atrial cells but not in normal ventricular cells [15, 23]. We were not able to find any studies on IKAS regulation in failing ventricles. Therefore, we [9] studied normal and failing rabbit hearts to determine if IKAS is upregulated in failing ventricles. A rabbit model of tachycardia-induced heart failure was used. Simultaneous optical mapping of Cai and Vm was performed in Langendorff-perfused failing hearts and normal hearts. The results show that after fibrillation–defibrillation episodes, acute but transient shortening of APD occurred in all failing ventricles. Figure 3a (left panel) shows Vm (black line) and Cai (red line) optical signals recorded during one of the SVF episodes. There were 2 post-shock beats (beats 1 and 2) before VF termination. Optical maps confirmed complete cessation of wave fronts after beat 2, consistent with type B successful defibrillation [22]. However, there was a large Cai transient and short APD (beat 3). The first beat of SVF (beat 4) began during late phase 3 of the preceding sinus beat. In Figure 3a (b), an isochronal map illustrates that beat 4 originated from the basal portion of the right ventricle. The right two columns are ratio maps of Vm and Cai, respectively, of the same beat. Cai remained increased throughout the mapped field, whereas Vm had already repolarized. The focal beat originated from the left upper quadrant during persistent Cai increase, consistent with the late-phase 3 EAD mechanism [4, 15]. Five SVF episodes were recorded after initial successful defibrillation in this failing heart. Apamin prevented both the post-shock APD shortening and SVF (Fig. 3b). We repeated fibrillation–defibrillation episodes four times, but no SVF was observed during the post-shock period after apamin.

Fig 3.

Pretreatment with apamin prevents late-phase 3 EAD and refibrillation. The black and red lines indicate optical tracings for Vm and Cai, respectively, obtained from the endocardial surface in a failing ventricle. A (a) Before apamin, a defibrillation shock (arrow) was followed by two post-shock beats (1 and 2). Optical maps (not shown) confirmed complete cessation of wave fronts after beat 2, consistent with type-B successful defibrillation. After a short pause, there was a large Cai transient (red dot), short APD (beat 3), and first beat (beat 4) of SVF arising from late phase 3. A (b) Snapshots of Cai and Vm ratio maps at times from 10 ms before to 20 ms after the onset of beat 4. Note that Cai remained increased throughout the mapped field, whereas Vm has already repolarized. Beat 4 increased during persistently high Cai and initiated the SVF. b After apamin (1 μM) infusion, post-shock beats 5 and 6 had longer APD than beats 1 through 4 in (A). APD and CaiTD were approximately the same, and SVF episodes were completely prevented. PM papillary muscle, S interventricular septum. From Chua et al. [9] with permission

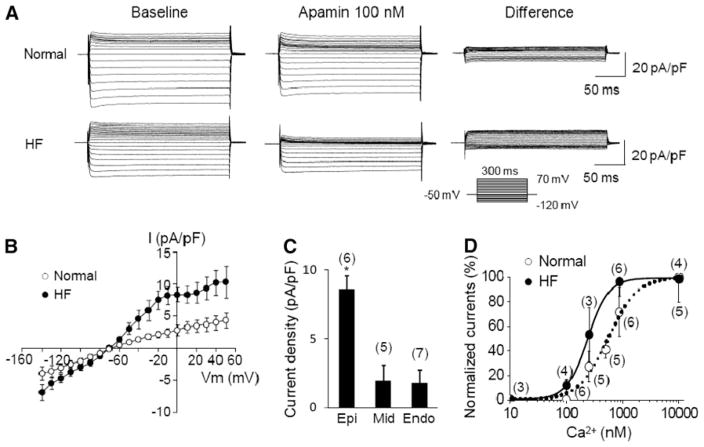

To directly document the upregulation of IKAS in failing ventricles, we performed patch clamp studies in failing and normal ventricles. The density and properties of IKAS were examined in cardiomyocytes isolated from normal and failing rabbit left ventricles using the voltage-clamp technique in whole-cell mode. Figure 4a shows representative current traces obtained with a step-pulse protocol in the absence and presence of 100 nM apamin in the bath solution. Mean IKAS density (determined as the apamin-sensitive difference current) was significantly greater in failing than in normal ventricular epicardial myocytes. In contrast, when the intrapipette free-Ca2+ was buffered to 100 nM, the apamin-sensitive current was much smaller, with no significant difference between normal and failing ventricular myocytes (Fig. 4d). Figure 4b illustrates the IKAS–voltage (I–V) relationships. Transmural distribution of IKAS in failing ventricles was studied using cardio-myocytes isolated from three layers (six epicardial cells, five midmyocardial cells, and seven endocardial cells from five animals). Mean IKAS density in epicardial myocytes was significantly greater than midmyocardial cells and endocardial cells (Fig. 4c). To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying IKAS upregulation, Ca2+-dependence of IKAS was studied in epicardial cells using pipette solutions containing increasing intracellular free Ca2+ concentrations. Figure 4d demonstrates that the steady-state Ca2+ response of IKAS was leftward-shifted in failing cells compared with the normal cells. The data were fitted with the Hill equation and yielded Kd of 232 ± 5 nM for failing and 553 ± 78 nM (p = 0.002) for normal cells and Hill coefficients of 2.38 ± 0.13 for failing and 1.50 ± 0.30 for normal cells (p = 0.01). These results are compatible with the notion that the K+ channels carrying IKAS have increased sensitivity to cytosolic Ca2+ in failing ventricles.

Fig 4.

IKAS in failing rabbit ventricles. a Representative K+ current traces obtained from normal (upper panel) and failing (lower panel) ventricular myocytes. Voltage-pulse protocol is shown in the inset. Baseline shows current traces in the absence of apamin (Ibaseline). “Apamin 100 nM” shows currents in the presence of 100 nM apamin (Iapamin). “Difference” shows IKAS calculated as Ibaseline − Iapamin. b I–V relationship obtained from normal (N = 6) and failing (N = 6) ventricular epicardial cells. c IKAS density at 0 mV with an intrapipette free-Ca2+ of 863 nM recorded from epicardial (Epi), midcardial (Mid), and endocardial (Endo) cells from five failing ventricles. *p < 0.05. d Steady-state Ca2+ response of IKAS in normal and failing epicardial ventricular myocytes. The data were fitted with the Hill equation: y = 1/[1 + (Kd/X)n], where y represents IKAS normalized to the currents with 10 μM intrapipette Ca2+; X is the concentration of Ca2+; Kd is the concentration at half-maximal activation; and n is the Hill coefficient. Error bars represent SEM. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of cells patched. From Chua et al. [9] with permission

Summary

In summary, simultaneous optical mapping of Cai and Vm demonstrated new mechanisms of EADs and cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Phase 3 EAD, which is dependent on prolonged APD, occurs through electrotonic interaction between regions with long APD and short APD. The large VG caused electrotonic current, which results in EAD in phase 3, TA, and arrhythmia. In contrast, late-phase 3 EAD is associated with APD shortening and persistent Cai increase. In failing ventricles, upregulation of IKAS underlies the mechanisms of post-shock APD shortening and recurrent SVF. The latter findings suggest that IKAS may be a novel antiarrhythmic targets in patients with heart failure.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants no. P01 HL78931, R01 HL78932, and HL71140 as well as a Medtronic-Zipes endowment.

Contributor Information

Peng-Sheng Chen, Email: chenpp@iupui.edu, Krannert Institute of Cardiology and the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1800N. Capitol Ave, E475, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Masahiro Ogawa, Department of Cardiology, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan.

Mitsunori Maruyama, Cardiovascular Center, Chiba-Hokusoh Hospital, Nippon Medical School, Chiba, Japan.

Su-Kiat Chua, Shin-Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Po-Cheng Chang, Krannert Institute of Cardiology and the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1800N. Capitol Ave, E475, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Michael Rubart-von der Lohe, Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Zhenhui Chen, Krannert Institute of Cardiology and the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1800N. Capitol Ave, E475, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Tomohiko Ai, Krannert Institute of Cardiology and the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1800N. Capitol Ave, E475, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Shien-Fong Lin, Krannert Institute of Cardiology and the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1800N. Capitol Ave, E475, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

References

- 1.Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Belterman CN, Coronel R, Fiolet JW. SR calcium handling and calcium after-transients in a rabbit model of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00854-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailie DS, Inoue H, Kaseda S, Ben-David J, Zipes DP. Magnesium suppression of early afterdepolarizations and ventricular tachyarrhythmias induced by cesium in dogs. Circulation. 1988;77:1395–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.6.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugada P, Wellens HJ. Early afterdepolarizations: role in conduction block, “prolonged repolarization-dependent reexcitation,” and tachyarrhythmias in the human heart. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1985;8:889–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1985.tb05908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Reinduction of atrial fibrillation immediately after termination of the arrhythmia is mediated by late phase 3 early afterdepolarization-induced triggered activity. Circulation. 2003;107:2355–2360. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065578.00869.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle NA, Haylett DG, Jenkinson DH. Toxins in the characterization of potassium channels. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PS, Antzelevitch C. Mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances. In: Valentin F, Richard AW, Robert H, editors. Hurst’s the heart. McGraw-Hill Professional; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi BR, Salama G. Simultaneous maps of optical action potentials and calcium transients in guinea-pig hearts: mechanisms underlying concordant alternans. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 1):171–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi BR, Burton F, Salama G. Cytosolic Ca2+ triggers early after depolarizations and torsade de pointes in rabbit hearts with type 2 long QT syndrome. J Physiol. 2002;543:615–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua SK, Chang PC, Maruyama M, Turker I, Shinohara T, Shen MJ, et al. Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel and recurrent ventricular fibrillation in failing rabbit ventricles. Circ Res. 2011;108(8):971–979. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.238386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damiano BP, Rosen MR. Effects of pacing on triggered activity induced by early afterdepolarizations. Circulation. 1984;69:1013–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.5.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidenko JM, Cohen L, Goodrow R, Antzelevitch C. Quinidine-induced action potential prolongation, early afterdepolarizations, and triggered activity in canine purkinje fibers. Effects of stimulation rate, potassium, and magnesium. Circulation. 1989;79:674–686. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.January CT, Chau V, Makielski JC. Triggered activity in the heart: cellular mechanisms of early after-depolarizations. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(Suppl F):4–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_f.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koretsune Y, Marban E. Cell calcium in the pathophysiology of ventricular fibrillation and in the pathogenesis of postarrhythmic contractile dysfunction. Circulation. 1989;80:369–379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama M, Lin SF, Xie Y, Chua SK, Joung B, Han S, et al. Genesis of phase 3 early afterdepolarizations and triggered activity in acquired long-qt syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:103–111. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagy N, Szuts V, Horvath Z, Seprenyi G, Farkas AS, Acsai K, et al. Does small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel contribute to cardiac repolarization? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa M, Morita N, Tang L, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN, Lin SF, et al. Mechanisms of recurrent ventricular fibrillation in a rabbit model of pacing-induced heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson E, Szabo B, Scherlag BJ, Lazzara R. Early and delayed afterdepolarizations associated with cesium chloride-induced arrhythmias in the dog. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;15:323–331. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson E, Lazzara R, Szabo B, Liu H, Tang D, Li YH, et al. Sodium–calcium exchange initiated by the Ca2+ transient: an arrhythmia trigger within pulmonary veins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1196–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szabo B, Kovacs T, Lazzara R. Role of calcium loading in early afterdepolarizations generated by Cs+ in canine and guinea pig Purkinje fibers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:796–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:45–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volders PG, Vos MA, Szabo B, Sipido KR, de Groot SH, Gorgels AP, et al. Progress in the understanding of cardiac early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes: time to revise current concepts. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:376–392. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang NC, Lee MH, Ohara T, Okuyama Y, Fishbein GA, Lin SF, et al. Optical mapping of ventricular defibrillation in isolated swine right ventricles: demonstration of a postshock iso-electric window after near-threshold defibrillation shocks. Circulation. 2001;104:227–233. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Tuteja D, Zhang Z, Xu D, Zhang Y, Rodriguez J, et al. Molecular identification and functional roles of a Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49085–49094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeh YH, Wakili R, Qi XY, Chartier D, Boknik P, Kaab S, et al. Calcium-handling abnormalities underlying atrial arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in dogs with congestive heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:93–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.754788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Kelley J, Schmeisser G, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR. Complex formation between junction, triadin, calsequestrin, and the ryanodine receptor. Proteins of the cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23389–23397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Timofeyev V, Lu L, Li N, Singapuri A, Long MK, et al. Functional roles of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel in atrioventricular nodes. Circ Res. 2008;102:465–471. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]