Abstract

This study tested the hypothesis that client choice influences intervention outcomes. We recruited 288 student drinkers (60% male, 67% freshmen) required to participate in an intervention due to a violation of campus alcohol policy. Participants were randomized either to self-chosen or researcher-assigned interventions. In the choice condition they selected either a brief motivational intervention (BMI) or a computer-delivered educational program. In the assigned condition they received one of the two interventions, assigned randomly. Follow-up assessments at 1- and 2-months revealed that choice was associated with higher intervention satisfaction. However, the assigned and choice conditions did not differentially change on consumption or consequences across intervention type. Overall, change scores favored the BMI over the computer-delivered intervention on consumption and consequences. Exploratory analyses revealed that, given the choice of intervention, heavier drinking students self-selected into the face-to-face BMI. Furthermore, among the students who received a BMI, the students who chose it (despite their heavier drinking) reduced drinks per drinking day more than the assigned students. In sum, offering a choice of intervention to students mandated for campus alcohol violations increased the chance that at-risk students will select a more intensive and effective intervention.

Keywords: college drinking, mandated students, self-determination theory, choice, autonomy support

Alcohol risk reduction interventions designed for college drinkers produce positive effects (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2007). An important subpopulation of college students are those required to participate in an alcohol intervention because they violated campus alcohol policies (i.e., mandated students). A growing number of well-designed studies document change in consumption and/or problems after interventions that are delivered in individual face-to-face format (e.g.,Borsari & Carey, 2005; Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2009; Doumas, Workman, Smith, & Navarro, 2011; White et al., 2006), by computer (e.g., Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007, Doumas, McKinley & Book, 2009), and in group format (e.g., LaBrie, Thompson, Huchting, Lac, & Buckley, 2007). Although participating in an intervention does produce more risk reduction than the disciplinary sanction alone (Carey, Carey, Henson, Maisto, & DeMartini, 2011; Terlecki, Larimer, & Copeland, 2010), mandated interventions are characterized by small effect sizes. Needed are improved interventions to boost efficacy for these at-risk drinkers.

Both clinical experience and research suggest that the intervention context for mandated students differs from that of students who volunteer for interventions. Reasons for referral vary from minor infractions of residence hall policy to more serious health or legal events related to alcohol (Barnett et al., 2008; Morgan, White, & Mun, 2008). Within mandated samples, students vary on the severity of their alcohol use and problems (Barnett et al., 2008). Not surprisingly, this sample heterogeneity results in differing student responses to the triggering events and the sanction process. Students who have been sanctioned for more serious events may respond with self-initiated change in alcohol consumption, whereas events perceived as less serious may not (Morgan et al., 2008). Perceptions of the aversiveness of the event vary depending on whether drinking on the day of the sanction event is more or less than typical drinking (Barnett et al., 2008; Carey & DeMartini, 2010). As a group, mandated students exhibit more defensiveness and less readiness to change than students who participate in interventions voluntarily, and defensiveness is associated with poorer outcome after a group intervention (Palmer, Kilmer, Ball, & Larimer, 2010). Thus, the efficacy of mandated interventions may be constrained by contextual variables that impact motivation for change.

Self-Determination Theory provides a theoretical context for enhancing motivation for change, positing three fundamental needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Optimal growth and development emerges from satisfying these basic needs and suffers when basic needs are not met. The literatures on mandated student interventions as well as other health behaviors both draw particular attention to the construct of autonomy support. Health behavior interventions that are perceived as supporting autonomy are more effective than those perceived as controlling (Sheldon, Joiner & Williams, 2003). Thus, contextual factors surrounding an intervention that nurture a person’s basic need for autonomy can help the person internalize intervention content (Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, & Leone, 1994; Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006). Furthermore, autonomously regulated behavior change is likely to be more enduring (Markland, Ryan, Tobin, & Rollnick, 2005).

Autonomy and perceived control may be fostered by incorporating an element of choice in a health behavior intervention (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006). Experimental evidence indicates that exercising control through choice is inherently rewarding (Leotti & Delgado, 2011). Furthermore, the perception of choice can promote intrinsic motivation, associated with task effort and persistence (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008).

Needs for autonomy and control may be threatened in the context of mandated interventions. Mandating participation in a behavior change intervention may undermine intrinsic motivation and engagement. Thus, providing an element of choice within a mandated intervention could enhance engagement and outcome. A growing literature on treatment preferences suggests that when patients have a preference, patients matched to preferred treatment leads to better engagement in medical (Preference Collaborative Review Group, 2008) and psychotherapy settings (Swift & Callahan, 2009). The most consistent effects of preference matching are seen on attendance (Janevic et al., 2003) and therapeutic alliance (Iacoviello et al., 2007), with inconsistent effects on clinical outcomes. A recent study with mandated college drinkers revealed that students who chose their intervention reported more satisfaction than those assigned to an intervention (Garey, Luteran, & Carey, 2010). However, no data are yet available on the effects of choice on drinking outcomes for mandated alcohol interventions.

The purpose of this study was to determine if choice of intervention affects drinking outcomes for students mandated to participate in an alcohol intervention. The two interventions used for this study were (a) a counselor-administered brief motivational intervention (BMI), and (b) Alcohol101+ ™, an interactive computer-delivered program. Both interventions consisted of a single hour-long session and were associated with reductions in drinking and related consequences among mandated students in our previous studies (e.g., Carey et al., 2009). We tested four hypotheses. First, based on our previous work (Carey et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2011) and that of others (e.g., Doumas et al., 2011), we predicted greater change after a counselor-facilitated BMI than after Alcohol101+ ™. Second, based on findings from medical and psychotherapy settings, we predicted that choice of intervention would lead to enhanced indicators of engagement after the single session as measured by (a) perceived control (cf. Ryan & Deci, 2000), (b) satisfaction with the intervention (cf. Garey et al., 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2000), and (c) motivation to change (cf. Patall et al., 2008). Third, based on Self-Determination Theory, we predicted that students given a choice of intervention would report improved outcomes (i.e., greater reductions in at-risk drinking and related consequences), relative to students who were assigned to the same two interventions. Fourth, we predicted that student characteristics would moderate the hypothesized effects of choice on outcome. That is, we expected that students whose basic needs for autonomy are met less well would respond most positively to having a choice of intervention, regardless of which intervention they choose.

Finally, with exploratory analyses we sought to identify predictors of intervention choice using demographics and drinking patterns, as well as theory-based person variables (e.g., extraversion or need for relatedness). Overall, the results of this study can be used to enhance the efficacy of mandated alcohol interventions and provide support for the application of Self-Determination Theory in the context of alcohol interventions.

Methods

Participants

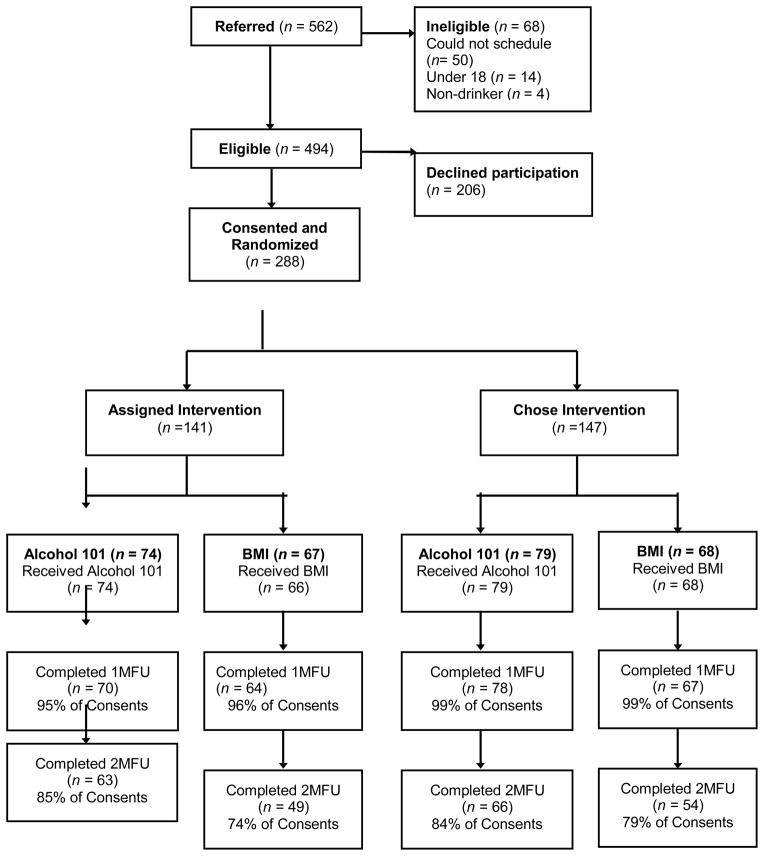

Students were eligible if they were over 18, had no previous alcohol policy violations, their offense did not involve additional behavioral infractions requiring referral to Judicial Affairs (e.g., assault, other drug use), and they reported drinking alcohol in the month before the sanction event. Of the 494 eligible students referred to the study by Residence Life staff, 58% consented to be in the study (see Figure 1). Thus, participants were 288 students (40% female) referred for first-time violations of residence hall alcohol policy. The majority were freshmen (67%) or sophomores (27%). Participants were predominantly white (86%), with 8% identifying as Asian and 4% as African-American. With regard to Greek status, 15% were members or pledges of a fraternity or sorority.

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Chart

Design

The design of this study combined both randomized and non-randomized components. As depicted in Figure 1, mandated students were randomly assigned to either the assigned (n = 141) or the choice (n = 147) arms. Within the assigned arm, they were further randomized to receive Alcohol101+ ™ (n = 74) or BMI (n = 67). The 147 students randomized to the choice arm selected their intervention type: 79 (54%) selected Alcohol101+ ™ and 68 (46%) selected a BMI.

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided information regarding age, gender, year in college, race/ethnicity, current residence, height, weight, and Greek affiliation.

Alcohol use

For all assessments, a standard drink was defined as a 12 oz. can or bottle of 4–5% beer; 5 oz. glass of 12% table wine; 12 oz. bottle or can of wine cooler; or 1.5 oz. shot of 80 proof hard liquor either straight or in a mixed drink (USDA, 2005). All assessments covered the month prior to the day of assessment.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) used a 7-day grid to assess drinking during a typical week of drinking in the previous month. The grid provides information for the calculation of total quantity in a typical week and typical drinks per drinking day. In response to supplemental questions, participants estimated the quantity and time spent drinking for their heaviest drinking night. Peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was estimated from the following formula: [(drinks/2) * (GC/weight)] − (0.016*hours), where (a) drinks = number of standard drinks consumed, (b) hours = number of hours over which the drinks were consumed, (c) weight = weight in pounds, and (d) GC = gender constant (9.0 for females, 7.5 for males) (Matthews & Miller, 1979).

Alcohol Problems

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1989) is a 10-item self-report screening assessment that is sensitive and specific in detecting harmful or hazardous alcohol use in the last year (Allen, Litten, Fertig, & Babor, 1997). Scores range from 0–40, and a score of 8 or higher suggests hazardous drinking (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). Coefficient alpha in the present sample was 0.77.

The 24-item Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) assessed the frequency of alcohol-related problems in the last month. Participants responded “yes” or “no” to 24 statements addressing possible problems during or following alcohol use (e.g., hangover, memory blackouts). Coefficient alpha in the present sample was 0.86.

Motivation for change

The Contemplation Ladder was adapted from a scale measuring readiness to change smoking (Biener & Abrams, 1991). Participants rated their motivation to change on a continuum ranging from a 0 (no thought of changing) to a 10 (taking action to change). The Contemplation Ladder and the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (Rollnick, Heather, Gold, & Hall, 1992) were highly correlated (r = .77) in a sample with male college students (LaBrie, Quinlan, Schiffman, & Earleywine, 2005).

Constructs derived from Self-Determination Theory

The Basic Needs Scale (BNS; Deci & Ryan, n.d.) is a 21-item measure that assesses the degree to which the psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are met in life. Participants rated the truth of statements such as “I really like the people I interact with” on a scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 7 (very true). These scales were administered at baseline and yielded the following coefficient alphas: Autonomy α = .63, Competency α = .73, and Relatedness α = .79.

The Self-Determination Scale – Perceived Choice (SDS-PC; Sheldon & Deci, 1996) is a five-question subscale of the Self-Determination Scale that assesses perceived choice/autonomy in life’s events. Each question consists of a pair of opposing statements labeled A and B (e.g., I feel pretty free to do whatever I choose to; I often do things that I don’t choose to). Participants rated which statement seemed more true for them “currently”, according to a five point scale (1 = Only A feels true to 5 = Only B feels true). This scale was administered immediately post-intervention, to assess whether the participants experienced the interventions in a manner consistent with the choice manipulation.

Personality

The Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) consists of 44 items assessing the personality dimensions of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Participants rated how well the statements (e.g., Tends to find fault with others) applied to them on a scale of 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The five subscales were internally consistent in the present sample (Openness α = .77, Conscientiousness α = .82, Extraversion α = .83, Agreeable α = .81, and Neuroticism α = .78).

Client Satisfaction

Participants rated the session on overall impression (1=very negative; 4=very positive); and whether they would recommend it (1=no, definitely not; 5=yes, definitely), and how informative, interesting, and helpful it was, all on 1 – 5 scales (1=not at all; 5=very),

Procedures

The Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Recruitment, consent, and baseline assessment

Students who violated campus alcohol policy were referred by staff at Residence Life to the research team. A Research Assistant (RA) explained to each referred student that (a) they were required to complete a sanction to remain in good standing, (b) the options for fulfilling the sanction were to complete either the standard sanction (an online alcohol course) or to participate in a research study; (c) participation in the research study through the one-month follow-up would fulfill the sanction; and (d) if students chose to participate, they would be invited to complete a paid 2-month follow-up assessment. Those who selected the standard sanction provided demographic information and completed the first three questions of the AUDIT, for descriptive purposes.

Students interested in satisfying their sanction through participation in the research study provided written consent and contact information, and then completed the online baseline assessment in a private office. At that point, participants were randomized to assigned or choice conditions; those in the assigned condition received their a priori and randomly determined condition assignment and those in the choice condition made their selection. All participants received an intervention appointment within two weeks. RAs who provided the instructions for the online assessments were different than those who conducted interventions.

Interventions

The BMI was administered in a single session lasting approximately one hour by one of 3 clinical psychology graduate student interventionists (2 female, 1 male), trained and supervised by the first author. To structure the session, interventionists provided a personalized feedback sheet that summarized drinking patterns (contrasted with gender-specific national and local norms), estimated typical and peak BAC, alcohol-related negative consequences and associated risk behaviors; interventionists also elicited personalized goal setting for risk reduction, and provided tips for safer drinking. The BMI was administered with a collaborative, supportive, yet directive style, consistent with motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Alcohol101+ ™ is an interactive CD-ROM program set on a “virtual campus,” wherein campus buildings represent venues with topics associated with alcohol use. Thus, students attend a virtual party to engage in social decision making, visit a virtual bar to learn about factors affecting their own BAC, and participate in a game show to test their knowledge about alcohol. The program is self-directed so that students navigate through the campus locations at their own pace. Participants had to spend at least 60 minutes exploring the program.

Follow-ups

RAs sent reminders for the 1- and 2-month follow-up assessments. Most of the online follow-up assessments were completed in the lab but 25% of 1-months were completed remotely and 53% of 2-months were completed remotely due to school breaks. Completion of the 1-month assessment satisfied the sanction requirement; students earned $20 for completing the 2-month follow-up.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To assess for recruitment bias, consenters (n = 288) and non-consenters (n = 135) were compared on gender, ethnicity, year in school, age, and the first 3 questions of the AUDIT. Consenters scored higher on all 3 AUDIT questions (all ps < .02), whereas Asian students were overrepresented in those who opted out of the research, χ2(5) = 26.70, p < .001. Consenters and non-consenters were equivalent on gender, age, and year in school.

As depicted in Figure 1, 97% of participants (95% in assigned; 99% in choice) provided data at 1 month and 80% provided data at 2 months (79% in assigned; 81% in choice). The choice condition was associated with lower attrition only at 1 month, χ2(1) = 4.94, p = .026. Gender, intervention type and drinking variables were unrelated to attrition.

Participants randomized to the assigned and choice arms did not differ on any demographic or drinking variables (see columns B and C in Table 1). Further randomization within the assigned arm to Alcohol101+ ™ (101) and BMI conditions also resulted in equivalent groups (columns D and E). Within the choice arm, self-selection into intervention group resulted in baseline differences (see Table 1). Students who chose BMI had higher AUDIT scores (10.19 vs. 8.33, t(141) = −2.13, p = .04), drinks per drinking day (5.58 vs. 4.16, t(142) = −2.49, p = .01), BYAACQ score (5.57 vs. 3.71, t(142) = −2.77, p = .01), and marginally higher drinks per week (15.45 vs. 12.16, t(139) = −.194, p = .06).

Table 1.

Demographics and Alcohol Variables at Baseline for Sample and by Condition

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Sample N = 288 | Assigned N= 141 | Choice N=147 | Assigned 101 N = 74 | Assigned BMI N = 67 | Chose 101 N=79 | Chose BMI N=68 | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Gender (% male) | 60% | 60% | 60% | 57% | 60% | 59% | 60% |

| Age | 18.60 (.71) | 18.60 (.70) | 18.59 (.73) | 18.55 (.67) | 18.66 (.74) | 18.48 (.86) | 18.72 (.76)* |

| Year (%freshman) | 67% | 65% | 69% | 61% | 69% | 74% | 63% |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 86% | 88% | 85% | 86% | 86% | 88% | 82% |

| Alcohol Use | |||||||

| AUDIT | 9.17 (5.04) | 9.12 (4.80) | 9.22 (5.28) | 9.10 (4.64) | 9.15 (5.00) | 8.33 (4.50) | 10.19* (5.91) |

| Drinks per Week | 13.26 (9.50) | 12.81 (8.80) | 13.70 (10.15) | 13.69 (9.28) | 11.87 (8.23) | 12.16 (8.93) | 15.45 (11.19) |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 4.61 (3.01) | 4.39 (2.46) | 4.83 (3.46) | 4.65 (2.62) | 4.10 (2.26) | 4.16 (2.55) | 5.58* (4.15) |

| Peak BAC | .160 (.097) | .164 (.092) | .155 (.101) | .170 (.094) | .159 (.091) | .152 (.082) | .157 (.119) |

| Consequences (BYAACQ) | 4.63 (4.22) | 4.67 (4.34) | 4.59 (4.12) | 4.20 (4.00) | 5.16 (4.65) | 3.71 (3.21) | 5.57* (4.78) |

Note.

means in columns F and G differ significantly (p < .05) using two-tailed independent samples t-tests. 101 = Alcohol101+ ™; BMI = Brief Motivational Intervention; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BAC = blood alcohol concentration; BYAACQ = Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire.

Intervention effects

To test the first hypothesis that mandated students who received a BMI would report greater changes in alcohol consumption and consequences compared to those who participated in Alcohol101+ ™, one-tailed independent samples t-tests were conducted with intervention condition as the independent variable. Dependent variables were the baseline (BL) to 1-month and BL to 2-month change scores of drinks per drinking day (DDD), drinks per week (DPW), peak BAC (pBAC), and alcohol related consequences. This hypothesis was supported in two of four primary outcomes at one-month, and all four primary outcomes at the 2-month follow-up. At the 1-month follow-up, students that received a BMI reported significantly greater reductions in pBAC (101: M = −.01, SD = .09 vs. BMI: M = −.04, SD = .10; t(270) = 2.42, p < .05) and consequences (101: M = −.57, SD = 2.86 vs. BMI: M = −1.47, SD = 4.20; t(270) = 2.08, p < .05) than those that received Alcohol101+™. At the 2-month follow-up, students that received a BMI reported significantly greater reductions in DDD (101: M = −.09, SD = 2.11 vs. BMI: M = −.89, SD = 2.91; t(221) = 2.39, p < .05), DPW (101: M = −.03, SD = 7.71 vs. BMI: M = −2.53, SD = 8.51; t(221) = 2.30, p < .05), pBAC (101: M = −.01, SD = .10 vs. BMI: M = −.04, SD = .09; t(221) = 2.55, p < .05), and consequences (101: M = −.67, SD = 3.38 vs. BMI: M = −1.67, SD = 4.41; t(221) = 1.94, p < .05) than those that received Alcohol101+™.

To test the second hypothesis, one-tailed independent samples t-tests compared assigned versus choice groups on enhancement of perceived control, satisfaction with the intervention, and motivation to change. Only intervention satisfaction differed by condition. Specifically, those who were given the choice of intervention reported greater satisfaction with the intervention compared to those assigned to an intervention (Assigned: M = 3.50, SD = .84 vs. Choice: M = 3.67, SD = .78; t(270) = −1.82, p < .05). No differences were observed on perceived control or motivation to change.

To test the third hypothesis, that students given the choice of intervention would report greater changes in alcohol use and consequences than those assigned to an intervention, one-tailed t-test were used compare outcomes on change scores at each follow-up. This hypothesis was not supported with any of the primary outcome measures at either 1-month or 2-months (all ps > .05). Given a priori predictions, the effect of intervention choice was tested within each intervention type (i.e. Alcohol101+ and BMI), again using one-tailed t-tests. Differences between students who were assigned versus chose the intervention emerged within intervention type. First, those who chose a BMI reported greater reductions in DDD (Assigned: M = −.14, SD = 2.09 vs. Choice: M = −1.01, SD = 3.41; t(270) = 1.79, p < .05) at the 1-month follow-up compared to those who were assigned to a BMI. Within conditions receiving Alcohol101+ ™, two unexpected findings emerged in the opposite direction of our hypotheses, and thus were explored using two-tailed tests. Specifically, those in the assigned Alcohol101+ ™ condition reported greater reductions in DDD compared to those who chose Alcohol101+ ™ (Assigned: M = −.51, SD = 2.23 vs. Choice: M = .17, SD = 1.52; t(142) = −2.12, p < .05) and DPW (Assigned: M = −2.33, SD = 6.92 vs. Choice: M = .30, SD = 7.29; t(142) = −2.17, p < .05) at the 1-month follow-up. Those who chose Alcohol101+ ™ did not change significantly from baseline to 1-month, as neither change score was significantly different from zero.

Moderation Analyses

To test the fourth hypothesis, that perceived autonomy at baseline would moderate the effect of choice on outcome, we used two sets of hierarchical linear regressions, predicting the four outcome variables at 1-month and again at 2-months. These analyses determined the interactive effects of baseline autonomy and assignment condition, after accounting for the other design dimensions of intervention type, gender and assignment alone. Only one of the models revealed significant moderation of assignment by baseline autonomy: DPW at the 2-month follow-up (b = 1.39, SE = 2.20, β = 1.00, p = .04). Consistent with predictions, greater reductions in DPW were observed for participants with low levels of felt autonomy in the choice condition. To illustrate, students with autonomy scores in the lowest third of the distribution reduced DPW more when they exercised choice (M = −3.72, SD = 9.46) than when they were assigned (M = .79, SD = 7.01), whereas students with autonomy scores in the highest third of the distribution did not differ (Assigned M = −1.49, SD = 7.35; Choice M = −2.10, SD = 7.29).

Predictors of Intervention Choice

To identify predictors of intervention choice, exploratory analyses were conducted using logistic regression. Alcohol consumption indices and alcohol-related consequences were entered as predictor variables in separate models predicting chosen intervention as the dichotomized dependent variable. Additional analyses evaluated personality and motivational variables as correlates of intervention choice.

The data contained in columns F and G of Table 1 reveal that students who chose the BMI over the 101 tended to be heavier drinkers. Logistic regressions using these drinking variables to predict choice (coded 1 = BMI, 0 = 101) revealed significant odds ratios for DDD (OR = 1.14, Wald (df = 1) = 5.49, p = .02) and consequences (OR = 1.13, Wald (df = 1) = 6.83, p = .01). Thus, for every additional drink per drinking day, the probability that a participant will choose BMI over 101 increases by 14%, and the probability of choosing BMI over 101 goes up 13% with every reported consequence on the problems measure.

Parallel analyses explored additional correlates of intervention choice, including motivation for change; Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness from the Basic Needs Scales; and the Big Five dimensions. None were associated with intervention choice (all ps > .10).

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the effect of choice of intervention on drinking outcomes for students sanctioned for violating campus alcohol policy. Mandated students were either randomly assigned or allowed to choose between two interventions (BMI and Alcohol101+ ™). From the students’ perspectives, these interventions varied in mode of administration (face-to-face vs. computer), degree of interpersonal contact, and expectancies of active engagement in intervention content, but they were similar in duration and number of visits, standardizing the demands on the student in structural terms. Four main findings emerged.

First, we found a main effect of intervention type on outcomes. Across both the assigned and choice arms of this study, students who received the BMI reduced their drinking and related consequences more than did students who received the computer-delivered intervention. This finding corroborates results from other studies in our lab that reveal more positive short- and long-term outcomes for face-to-face interventions for mandated students (Carey et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2011). It is possible that counselor-delivered interventions may engage the attention of mandated students to a greater extent than computer-delivered interventions, and a counselor may be able to address issues such as resistance more effectively. However, we must acknowledge that the two interventions represented in this study differed not only on mode of administration but also on content, thus conclusions must be limited to these particular instantiations of counselor- and computer-delivered interventions.

Accumulated data suggest that when differential effects are found for face-to-face BMIs relative to other active interventions, the outcomes always favor BMI (see also Borsari & Carey, 2005; Doumas et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2010). One might speculate that the use of motivational interviewing principles by a skilled counselor would be particularly suited to engaging mandated students in risk reduction efforts. In fact, a recent meta-analysis suggests that the BMI format produces stronger effects when used with mandated students than other students (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that a BMI may be an intervention of choice for mandated students.

Second, being able to choose between two interventions to satisfy the sanction requirement did not enhance outcomes over being assigned to the same interventions. We found that choice was associated with slight increase in client satisfaction with the chosen intervention, However, contrary to our predictions, we did not find a main effect of choice on our theoretically-derived intermediate outcomes (motivation and perceived choice) or the main outcomes. A more nuanced picture emerged when we looked at the effect of choice within each intervention type. Even though the efficacy of and satisfaction with the assigned BMI were high, the element of choice enhanced outcomes. Previous research evaluating the BMI with both mandated and volunteer students reveals robust effects; students generally like the intervention and reliable reductions in drinking and consequences ensue (Borsari & Carey, 2005; Butler & Correia, 2009; Carey et al., 2009). In the current study, the students selecting the BMI drank more than those assigned to BMI, but also reduced their drinking to a greater extent. While regression to the mean is one alternative interpretation, it is important to note that the imbalances between the BMI groups on baseline drinking were not a methodological artifact, but a result of self-selection that cannot be fully controlled for statistically (cf. Lord, 1967). For the Alcohol101+ ™ intervention, choice increased satisfaction with the intervention (consistent with the findings of Garey et al., 2010), but it did not improve outcomes. Perhaps because students who selected the Alcohol101+ ™ intervention tended to be lighter drinkers than those who selected a BMI, they reduced their drinking less at follow-up than the students with a wider range of drinking patterns who got assigned to that intervention. Thus, when given the choice, lighter drinkers who were less interested in changing their drinking chose the less personal computer-administered intervention. Our ability to detect a main effect of choice may have been obscured by self-selection on the basis of drinking habits.

Third, heavier drinking students were more likely to select the face-to-face BMI, and this BMI is consistently associated with better outcomes. Thus, an unexpected positive outcome of offering choice is that some students engaging in risky drinking behaviors will seek out more intensive intervention if given the option. We examined a number of potential predictors of intervention choice, but only baseline drinking predicted intervention choice. Hence, choice may be a mechanism to bring the riskiest drinkers into contact with a counselor. This outcome highlights the limitations of relying solely on computer delivered interventions despite their efficiency (cf. Carey et al., 2009), and also the value of having a continuum of prevention and early intervention strategies available for college drinkers. If the default is a brief computerized intervention, it may be clinically wise to offer the choice of a face-to-face intervention with a counselor who can tailor the intervention to riskier drinkers and assess the need for more intensive intervention options.

Fourth, expectations that satisfaction of basic autonomy needs at baseline would moderate the impact of intervention choice were partially supported. Results for DPW at 2-month follow-up showed that low autonomy enhanced outcomes in the choice condition. It is unclear why the predicted moderation effect was seen on just one of the measured outcomes. We can speculate that DPW may have been more sensitive to changes in frequency of consumption, whereas DDD and peak BAC capture quantity during drinking occasions. Overall, however, the hypotheses derived from Self-Determination Theory received only partial support. It is unclear whether the theory does not apply as well in this context as it does in others, or if the tools used to measure its constructs are not as sensitive when used with college drinkers as they are with other populations. In light of recent reviews of how Self-Determination Theory and motivational interventions may mutually inform each other (Markland et al., 2005; Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006), additional research is needed to determine its relevance to college drinking interventions.

Strengths and limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Strengths included (a) testing theory-driven hypotheses about ways to enhance the efficacy of existing intervention options for mandated students, (b) recruitment of heavier drinkers from the pool of eligible referrals, and (c) evaluating the appeal of interventions equivalent on time commitment but differing on mode of administration.

The limitations of this study must also be acknowledged. First, all participants exercised choice (i.e., whether to participate in the research study) and all did not (i.e., they were mandated to receive an intervention), potentially minimizing the difference between the choice and assigned conditions. Perhaps because the act of electing to participate in the research satisfied the need for autonomy sufficiently, the additional element of choice built into the study did not result in measurable enhancement of perceived control after intervention. Thus, this study was not a pure test of choice. Second, we assessed only short-term (i.e., 2 month) drinking outcomes. Longer follow-ups are necessary. Third, our sample was relatively homogeneous, consisting of primarily white students attending a private four-year university; this restricts generalizability of the findings. Fourth, we evaluated the effect of choice with only two interventions; alternative interventions may reveal additional self-selection processes. Fifth, we explored a limited set of possible predictors of intervention choice. Other dimensions of personality or temperament, or factors such as family history of alcohol problems might predict selection of intervention. Finally, we did not assess the students’ intervention preferences in the assigned condition. Some in the assigned arm of the study might have been equivalently satisfied with their assignment as those who chose their preferred intervention, whereas some may have wanted the alternative they did not get. Given the small but significant effects of receiving a preferred treatment on outcomes (Swift & Callahan, 2009), the effect of this combination of matches and mismatches could have lessened the differences between the choice and the assigned conditions.

Overall, offering a choice of intervention to students mandated for campus alcohol violation improves satisfaction but not outcomes. Our results indicated that the heaviest drinking students (i.e., those who could most benefit from risk reduction) actually preferred the BMI, and for all mandated students, a BMI will produce better short-term outcomes than assigning them to an interactive computer-delivered intervention such as Alcohol101+ ™.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIAAA Grant R01-AA012518 and K02-AA015574 to Kate B. Carey. The authors thank Jamie Bolles, Lorra Garey, Annelise Owen, and Danielle Seigers for their significant contributions to this research.

References

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines For Use In Primary Care. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines For Use In Primary Care. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Borsari B, Hustad JTP, Tevyaw TO, Colby SM, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Profiles of college students mandated to alcohol intervention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:684–694. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy and mediation of counselor vs. computer delivered interventions with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for referred students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LH, Correia CJ. Brief alcohol intervention with college student drinkers: face-to-face versus computerized feedback. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:163–167. doi: 10.1037/a0014892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Henson JM, Maisto SA, DeMartini KS. Brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students: Comparison of face-to-face counseling and computer-delivered interventions. Addiction. 2011;106:528–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, DeMartini KS. The motivational context for mandated alcohol interventions for college students by gender and family history. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Computer versus in-person intervention for students violating campus alcohol policy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:74–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon L, Carey MP, DeMartini K. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Unpublished manuscript. Brown University; 2011. Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Eghrari H, Patrick BC, Leone DR. Facilitating Internalization: The Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:119–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Basic Need Satisfaction in General. n.d Retrieved June 15, 2008, from http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/bpns_scale.php.

- Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Workman C, Smith D, Navarro A. Reducing high-risk drinking in mandated college students: Evaluation of two personalized normative feedback interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;40:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Luteran C, Carey KB. Mandated students’ satisfaction with assigned and chosen interventions. Poster presented at the 44th annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; San Francisco, CA. 2010. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Iacoviello BM, McCarthy KS, Barrett MS, Rynn M, Gallop R, Barber JP. Treatment preferences affect the therapeutic alliance: Implications for randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):194–198. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janevic MR, Janz NK, Dodge JA, Lin X, Pan W, Sinco BR, Clark NM. The role of choice in health education intervention trials: a review and case study. Social Science Medicine. 2003;56:1581–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The big-five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Thompson AD, Huchting K, Lac A, Buckley K. A group motivational interviewing intervention reduces drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences in adjudicated college women. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2549–2562. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Quinlan T, Schiffman JE, Earleywine ME. Performance of alcohol and safer sex change rulers compared with readiness to change questionnaires. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:112–115. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;31:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, Delgado MR. The inherent reward of choice. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1310–1318. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM. A paradox in the interpretation of group comparisons. Psychological Bulletin. 1967;68:304–305. doi: 10.1037/h0025105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:811–831. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TJ, White HR, Mun E. Changes in drinking before a mandated brief intervention with college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:286–290. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:628–639. doi: 10.1037/a0021347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Kilmer JR, Ball SA, Larimer ME. Intervention defensiveness as a moderator of drinking outcome among heavy-drinking mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1157–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patall EA, Cooper H, Robinson JC. The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:270–300. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preference Collaborative Review Group. Patients’ preferences within randomized trials: Systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:a1864. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short “readiness to change” questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Deci EL. Unpublished manuscript. University of Rochester; Rochester, NY: 1996. The Self-Determination Scale. Retrieved June 15, 2008 from http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/sds_scale.php. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Joiner T, Williams G. Motivating health: Applying self- determination theory in the clinic. Yale: Yale University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, Callahan JL. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:368–381. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecki MA, Larimer ME, Copeland AL. Clinical outcomes of a brief motivational intervention for heavy drinking mandated college students: a pilot study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 6. U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste M, Sheldon KM. There’s nothing more practical than a good theory: Integrating motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;45:63–82. doi: 10.1348/014466505X34192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:982–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, LaBouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]