1. Channelopathies: diseases of abnormal ion channel function

Ion channel proteins form pathways for charged ions to cross the hydrophobic barrier of the cell membrane. The physiological importance of ion channel proteins is highlighted by a group of diseases, called channelopathies, where genetic mutations alter channel function and are associated with disease pathogenesis. At the cellular or tissue level the pathological phenotype is often described as a simple gain or loss of channel current but the molecular details often reveal unappreciated complexity. Identification and detailed description of the functional abnormalities the mutations produce have the potential to improve prognostic precision and pharmacological therapy. This review aims to show the bases of channelopathies by illustrating with didactic examples how the molecular properties of a population of ion channels contribute to the generation of a macroscopic ionic current and how mutations change these molecular properties to generate abnormal currents and cause channelopathies.

2. Ion channel structure and function

The phospholipid bilayers of biological membranes compartmentalize cells by impeding the diffusion of hydrophilic molecules in and out of the cell or internal organelles they surround. Therefore, the only path for these species to cross the membrane is through an ion channel or transporter protein embedded in the membrane. The ionic currents that flow passively through ion channels can generate dynamic electrical signals, transfer ions across compartments, and couple to intracellular biochemical pathways. Two fundamental properties of ion channels, selectivity and gating, allow for organized ionic permeation while maintaining the barrier property of the membrane1.

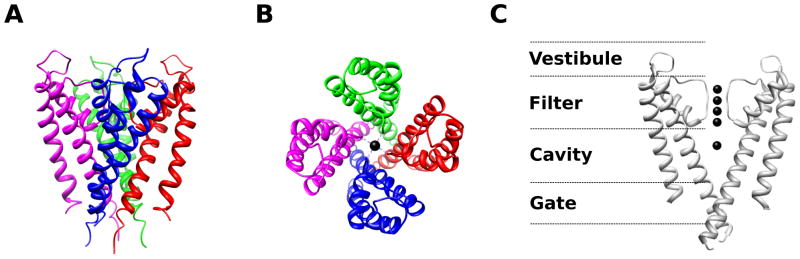

Selectivity refers to the ability of an ion channel to allow the rapid flux of a particular ionic species across the membrane while preventing the permeation of others. The structural determinants of selectivity have been mapped in many channels to a filter-like structure in the central pore that provides direct interactions to substitute for some or most of the waters of hydration that surround the ion in solution2–7 (see Fig. 1). Selectivity arises from the strength of these ion- filter interactions. Ions that cannot make energetically favorable interactions are unable to shed their waters of hydration to enter the filter. Ions that interact too favorably with the filter will get stuck in the filter and not permeate well, as in the case of some blocking ions8. The optimally permeated (selected) ions are those that desolvate, move through the filter, and resolvate on the other side with a smooth energy landscape allowing for rapid permeation in the absence of significant energetic barriers or wells9. Importantly, selectivity is a key determinant of which direction the net current will proceed through the open channel (see below).

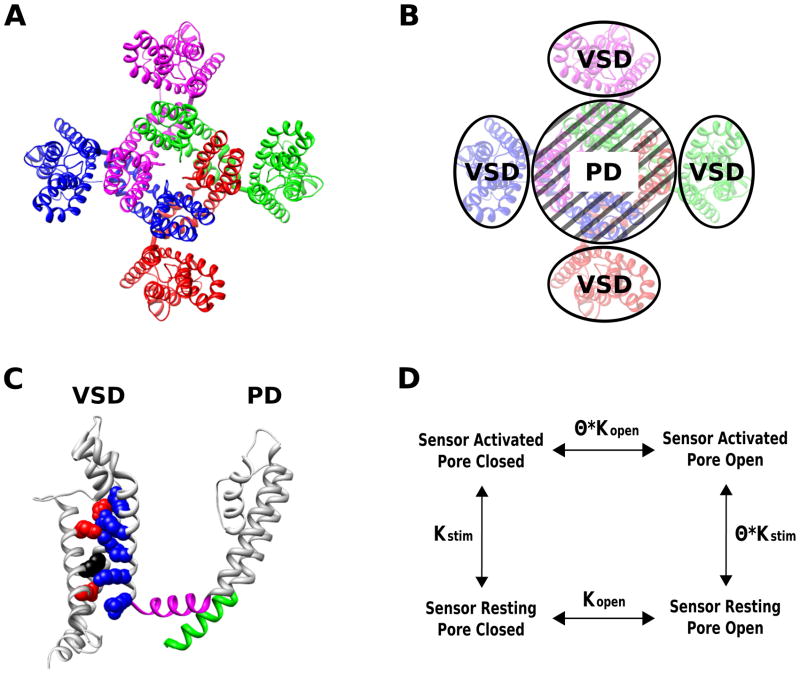

Figure 1.

A crystal structure of the KCSA potassium (K+) channel from Streptomyces lividans3 (PDB 14KC) reveals structural determinants of selectivity and gating. Four KCSA subunits (indicated by different colors) coassemble to form a tetrameric pore structure (A – side view, B – top view). The important structural features are highlighted in panel C – the extracellular vestibule, selectivity filter, pore cavity, and intracellular gate (only two subunits of the tetramer are shown for clarity). Black spheres indicate resolved ions in the filter. The selectivity filter contains a sequence of amino acids (TVGYG) that is highly conserved among K+ channels. The selectivity filter is so narrow that the K+ ions must lose waters of hydration in order to fit. The large energetic penalty associated with desolvation is compensated by interactions with backbone carbonyls of the selectivity filter. Na+ ions do not have the correct geometry to establish stabilizing interactions with the potassium selectivity filter, making the permeability of Na+ through KCSA less likely than K+. In contrast, Rb+, which has a similar geometry as K+, permeates approximately as well as K+ through KCSA4,9. The presence of multiple ions within the selectivity filter allows for rapid permeation of K+ because the repulsive forces between the ions can dislodge the K+ from the stabilizing interaction sites within the filter9. The entry of a new ion into filter pushes the other filter ions along resulting in one ion leaving the filter from the other end. This mode of permeation is analogous to the current in a wire where the rate of current flow is much faster than the drift velocity of individual electrons – even though the entering K+ has only moved part of the way through the filter, one positive charge has been translocated completely across the membrane. The central cavity of the pore is a wide hydrophobic tunnel filled with water molecules that allows for the ion to rejoin with waters of solvation and to continue through the permeation pathway without significant interactions with the protein surface. At the intracellular gate the inner helices of the four subunits form a bundle crossing that creates an impassable constriction of the permeation pathway in the closed state. As revealed by functional studies and the channel structures10,12–18,21, local conformational changes around the intracellular gate lead to dilation of the permeation pathway allowing for the passage of ions at the open state. Structural studies show that Na+ and Cl− channels share similar principles of ion selectivity and permeation6,199–201.

Ion channels have evolved various mechanisms through which the ionic conductance can be turned on and off, a process known as gating, in response to various cellular signals. This process often involves a conformational change in the pore structure resulting in an opening or impassable constriction of the ionic pathway10–21. The stimuli for gating can be diverse and many ion channels contain modular domains that directly sense the stimulus and then modulate the pore through domain-domain interactions (see Fig. 2 for voltage-gated channel example). In other cases, the sensor and the pore are not distinct structural elements22–23. In either case, gating involves coupled sensing and transduction steps involving several conformational states. The consequences of gating behavior are dynamic ion fluxes that are responsive to chemical and physical stimuli arising from physiological processes. At the level of a single channel, opening is stochastic and binary. The channel will exhibit sojourns of zero (closed) and full (open) conductance of varying duration24 (Fig. 3A). Gating stimuli modulate the probability of entering or exiting a sojourn. The conductance of a single channel when open is primarily determined by the permeation properties of the pore; while separately, the probability that the channel is open depends mainly on its gating properties1. Of course these are simplifications as states with various conductances are possible25, and permeation and gating are not always independent26–27. However, this approximate model of the single channel behavior holds well enough to provide a description of the molecular underpinnings of channelopathies.

Figure 2.

The structure of the voltage-gated, chimeric Kv1.2/2.1 K+ channel reveals the regulation of channel open probability by modular sensor domains150. Voltage-gated K+ channels are formed by four subunits (indicated by different colors in A,B) and each of the subunits contains a pore domain and a voltage-sensing domain (VSD) (C). The VSD contains four transmembrane helices (S1–S4), while the pore, like the KCSA pore (Fig. 1), is formed by the coassembly of the pore domains (S5–S6) of all four subunits. The structure clearly reveals the channel’s modular nature consisting of the conserved, central K+ selective pore surrounded by the VSDs (B). VSDs as a structural module have been found in other voltage-gated channels as well as non-ion channel proteins22–23,202–204. The VSD contains a series of positively charged residues in the S4 helix, and the membrane potential exerts a force directly upon these charges to displace the S4 segment outward or inward187,205–210. Within the S2 and S3 helices, negatively charged residues are positioned to interact with S4 charges, providing electrostatic forces to stabilize the S4 within the membrane and define the trajectory of the S4 movement6,150,211–213. In voltage-gated K+ channels the outward translation of the S4 helix exerts a force on the S6 segment (green) through the S4–S5 linker (magenta) that promotes the dilation of the intracellular gate to open the channel pore214–217, and S4–S5 linker to gate interactions are found in other voltage-gated channels as well218–219. Because of these interactions the activation of the VSD and the opening of the pore domain are coupled such that the activation of the sensor increases the probability of the opening of the pore (D). The scheme in panel D represents a general description of the regulation of a channel pore by modular sensor domains. In the scheme, Kstim represents the equilibrium constant for sensor activation which is a function of physiological stimulation, Kopen is the equilibrium constant for the intrinsic pore opening which is independent of the presence of stimulation, θ represents the coupling between the sensor and pore domains whereby sensor activation in response to stimiulation leads to increased pore opening.

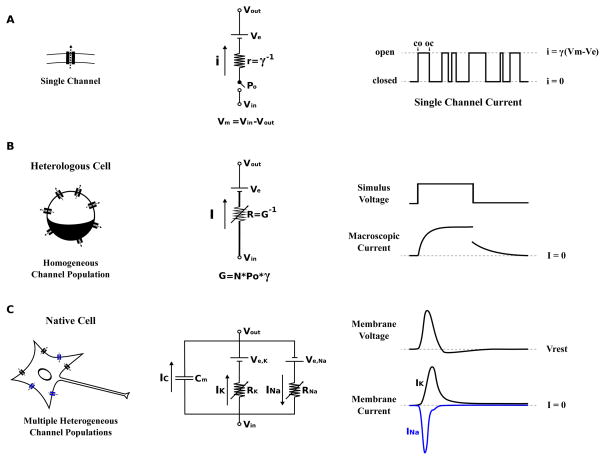

Figure 3.

The various scales of electrophysiology. (A) The single ion channel is the molecular determinant of cellular electrophysiology and the therapeutic target for pharmacological approaches to treating channelopathies. At the level of the single channel the current is all or nothing24 due to the opening and closing of the channel gate(s) (right, CO and OC indicate the first closed to open and open to closed transitions respectively). A circuit model consisting of a battery (Ve), a resistor (r), and a switch (Po) can be used to represent a single ion channel (center). The battery represents the potential generated by asymmetric distribution of permeant ions (the Nernst potential). The selectivity property of the channel determines what ions will permeate and therefore helps to determine the value of Ve. The resistor reflects the ability of the channel to conduct ionic current, resistance is the inverse of conductance (r=γ−1). The switch represents the gating property of the channel through which the conductance can be turned fully on or off (single channel current is all or none). The probability that the switch is open is determined by the probability that the channel gate(s) are open. By convention the membrane potential is defined with respect to the potential inside the membrane (Vm=Vin−Vout). The difference between the membrane potential and the equilibrium potential (Vm−Ve) is called the driving force. This is the equivalent potential that is dropped across the resistor and is therefore linearly related to the magnitude of the current through the resistor by ohms law (Equation 3). (B) Expressing ion channel proteins in heterologous cells, such as Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cell lines (eg. Chinese Hamster Ovary and Human Embryonic Kidney 293 cells), allows for the observation of currents generated by an essentially homogenous population of channels due to relatively low expression of channel proteins in these cells. Macroscopic currents recorded from these cells reflect the summed ensemble of many single channel currents resulting in an apparently smooth response to stimulation. For this reason, the circuit model of a channel population lumps single channel conductance (γ) and the open probability (Po) with the total number of channels (N) into the macroscopic conductance (G). In the circuit model G is represented as a variable conductor as Po changes in response to physiological stimuli (Equation 4). (C) Native cells are yet more complex as they express many different populations of ion channels in the membrane. These channel populations that are coupled through both the membrane potential and physical-chemical environment. Take a simple case of a cell containing only two channel populations; one Na+ channels (Na+ selective), the other K+ channels (K+ permeable), and both are activated by voltage. The opening of the Na+ channels will bias the membrane potential toward the equilibrium potential for Na+ (usually around +50 mV). This depolarization of the membrane potential will open the voltage activated K+ channels that in turn bias the potential back toward the K+ equilibrium potential (usually around −70 mV) meanwhile Na+ channels are closed by inactivation (see main text for the description of inactivation) allowing the K+ channels to dictate the membrane potential. This interplay between the channel populations results in the generation of dynamic electrical signals, known as action potentials, that depend on the properties, shown in Equation 4, for all channels present. Models of these complex systems can be built by connecting the models of individual channel populations (like in B, center) in parallel220. In all these circuit models (A–C) the ability of the membrane to separate charged ions is represented as a capacitor in parallel (as shown in C, center).

Gating and selectivity allow ion channels to tune the ionic permeability of the membrane; however, the permeability simply provides a pathway for ions to move across the membrane. The magnitude and direction of the resulting flow of ions (ie. current) across the membrane will depend on the chemical and electrical forces driving the ions from one side of the membrane to the other. The chemical component comes from asymmetric distribution of ions across the membrane; while the force of the membrane electric field on the charged ion causes the electrical component. At a transmembrane potential of 0 mV (electric component is zero), asymmetric distribution of ions across the membrane will drive a net ionic flux through the membrane due to diffusion (via open channels that selectively permeate the ions), leaving behind an imbalance of charges that alters the transmembrane potential. In the case of a single permeant ion this process will continue until force of the electric potential generated by the charging of the membrane drives an ion flux sufficient to exactly counteract the diffusional ionic flux. At this potential, which is termed the equilibrium potential (Ve), the net transmembrane flux of the ions will be zero. Because relatively few ions have to cross to charge the membrane, the equilibrium potential is reached without significantly changing the concentrations of ions on each side of the membrane. Therefore, the equilibrium potential is solely determined by the concentration gradient of the ion across the membrane and can be calculated using the Nernst equation (Equation 1)28.

| (Equation 1) |

Ve is the equilibrium potential (V)

R is the universal gas constant (J K−1 mole−1)

T is the absolute temperature (K)

z is the valence of the permeant ion

F is the Faraday constant (C mole−1)

[ion]in is the concentration of the permeant ion inside the membrane (M)

[ion]out is the concentration of the permeant ion outside the membrane (M)

If only one permeant ion is present and the membrane potential is different from the equilibrium potential a net ion movement will be generated until the membrane potential is equal to the equilibrium potential. In a more physiological situation, there are multiple ionic species to which the membrane is permeable (ie. contains open ion channels of appropriate selectivity). The current through each open channel will bias the membrane potential toward the equilibrium potential for selected ions. As a result of the competition among these various conductances the equilibrium potential of a single ion is not realized. Rather, a steady-state resting potential that is in between the equilibrium potentials of the various ions will be established at which point the net current, rather then the net flux of any particular ion, will be zero. Because there is a net flux of individual ion species at the resting potential the ionic gradients would be dissipated over time. However, biological membranes contain active transporter proteins that move ions against their electrochemical gradient by hydrolyzing ATP or utilizing gradient of other ions. These transporters maintain the asymmetric distribution of ions across the membrane. If only monovalent ions are taken into account and the small but significant contribution of electrogenic transporters is ignored29, the resting potential can be calculated as an average of the equilibrium potentials of the various ions weighted by the relative permeability of the membrane to those ions, as in the Goldman- Hodgkin-Katz equation (Equation 2)28. This is often an accurate approximation as the permeability to divalent cations is low in many cells at the resting potential.

| (Equation 2) |

Vrest is the resting (steady-state) potential (V)

R is the universal gas constant (J K−1 mole−1)

T is the absolute temperature (K)

F is the Faraday constant (C mole−1)

Pcation is the relative permeability of the membrane to cation x

[cation]in is the concentration of cation x inside the membrane (M)

[cation]out is the concentration of cation x outside the membrane (M)

Panion is the relative permeability of the membrane to anion x

[anion]in is the concentration of anion x inside the membrane (M)

[anion]out is the concentration of anion x outside the membrane (M)

In cells, the major permeant cations are sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and calcium (Ca2+) while the major permeant anion is chloride (Cl−). Under certain conditions the permeability of the membrane is dominated by a single ion and the resting potential approaches the equilibrium potential for that ion. For instance, the resting membrane potential of a neuron lies close to the equilibrium potential for K+ because the nerve cell membrane at rest is far more permeable to K+ than Na+ or Ca2+, while chloride is passively distributed.

Generally, the current carried through a membrane by one ionic species is linearly related to the membrane potential. The difference between the membrane potential and the equilibrium potential, which quantifies the driving force, dictates the magnitude and the direction of the current. This linearity breaks down when conductance is a function of voltage as in the voltage-gated channels (see section 3.3) or rectifying channels where charged blocker molecules bind within the membrane electric field causing the I–V relation to deviate from linear.

| (Equation 3) |

Ix is the current carried by ion x (A)

Gx is the conductance of the membrane to ion x (S)

Vm is the membrane potential (V)

Ve is the equilibrium potential for ion x (V)

(Vm−Ve) is the driving force (V)

If the membrane potential is more positive than the equilibrium potential, the driving force (Vm−Ve) will be positive and the current carried by the movement of the ions will be outward. On the other hand if the membrane potential is more negative than the equilibrium potential the driving force will be negative and the current will flow inward. Ultimately, it is the net macroscopic current across the whole membrane, as described by equation 3, that affects ionic homeostasis and transmembrane potential (outward current hyperpolarizes the membrane while inward current depolarizes the membrane). This macroscopic current is the sum of all of the currents generated by individual ion channels in the membrane (Fig. 3B). Therefore, to express the total current (Ix) in terms of the molecular properties of single ion channels, equation 3 can be expanded as follows:

| (Equation 4) |

I is the macroscopic current generated by a homogeneous population of ion channels (A)

N is the number of ion channels in this population

γ is the conductance of a single open ion channel (S)

Po is the probability that the channel is open

Vm is the membrane potential (V)

Ve is the equilibrium potential for the ion selected by the channel (V)

Mutations in genes encoding ion channels can alter the number of channels (N) in the membrane, the single channel conductance (γ), the gating (Po), or the selectivity that determines the equilibrium potential (Ve). These changes in molecular behavior result in a pathological increase or decrease of the macroscopic current. Through the following examples we will demonstrate the mechanisms through which mutations alter each of the molecular properties of ion channels (N,γ,Po,Ve), change cellular electrophysiology, and are linked to disease symptoms. The characterization of the molecular mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis is of great importance to the design and selection of therapeutics. Unfortunately, many mutations can affect multiple channel properties, making effective treatment challenging.

3. Disease-associated mutations alter ion channel properties

3.1. Number of channels (N)

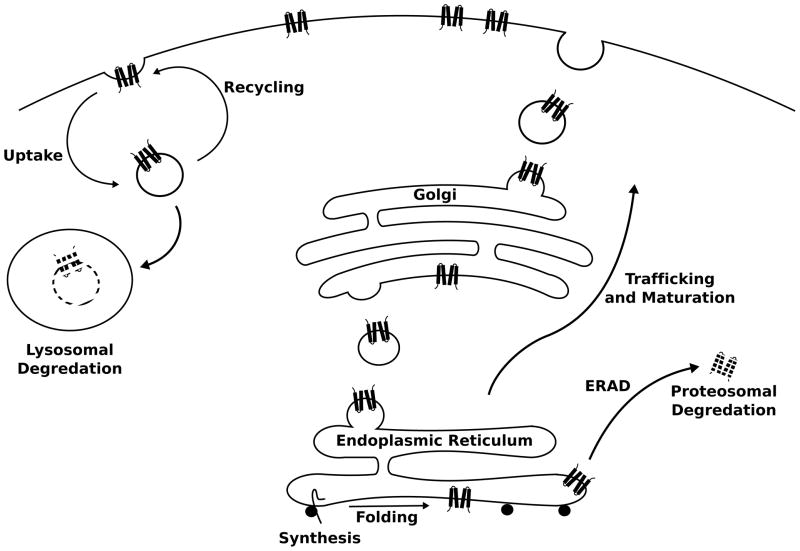

The lifecycle of an ion channel is multifaceted and dynamic. Peptide synthesis and folding of the nascent chain into the quaternary channel structure occurs in the ER. Posttranslational modification, which decorates the protein with sugars and other regulatory molecules, occurs as the channel is trafficked through the ER and golgi networks before the mature protein is delivered to the target membrane. After some time in the membrane, channels are returned to the cytoplasm in vesicles for recycling back to the membrane or targeting to the lysosome for degradation (Fig. 4). This balance between synthesis, degradation, and relocation presents many points for the regulation or pathological dysregulation of the number of channels in a target membrane, sometimes leading to disastrous results.

Figure 4.

Metabolism of ion channel proteins. Ion channels are synthesized into and across the membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Channels that achieve a proper fold go on to traffick through the ER and Golgi comparment while undergoing post-translational modifications en route to the target membrane. Improperly folded channels are recognized by the ER quality control machinery and targeted for removal from the ER membrane and proteasomal degredation within the cytosol. After a period of residency within the target membrane, mature channels are uptaken from the membrane into vesicles that can be later returned to the membrane (recycling) or targeted to the lysosome for degredation95.

3.1.1. CFTR ΔF508: a poorly folded channel

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common fatal inherited disease among the white population30. CF is an autosomal recessive disorder involving multi organ dysfunction associated with defective epithelial chloride conductance31–33. Among these sequelae the resulting pulmonary disease is the largest cause of morbidity and mortality. In the lungs chloride efflux into the airspaces is critical to the transport of ions and water for the maintenance of mucous hydration and effective mucociliary clearance. In CF patients, blockage of airways by thick mucous leads to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, repeated infections, and ultimately degeneration of the lung parenchyma. Genetic mutations in CF patients have been localized to a gene encoding the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator (CFTR), which belongs to the ATP binding cassette family of transporters34–36. However, CFTR is not a transporter, but instead carries a passive chloride conductance that is activated by protein kinase A (PKA) dependent phosphorylation and direct binding of ATP37–41. The mutation found in the majority (> 70 % of CF patients of European descent34) of CF patients causes the deletion of phenylalanine 508 (ΔF508) resulting in channels that fail to achieve the complex glycosylation pattern that is characteristic of the mature wild type (wt) CFTR42. Lowered temperature can rescue the maturation defect of ΔF508 suggesting that ΔF508 is associated with a conformational change that prevents the mutated channel from reaching the maturation43–44. Consistent with this idea, limited proteolysis shows that the conformation of ΔF508 is different from mature wt CFTR, but resembles a folding intermediate of wt CFTR. Furthermore, the kinetics and pathway of degradation of ΔF508 and the poorly folded wt CFTR intermediate are similar45. These results suggest that ΔF508 stabilizes an improperly folded conformation of CFTR that is recognized by the ER quality control machinery and prevented from progressing to the golgi where it would have been glycosylated46. The poorly folded wt and mutant subunits are ubiquitinated, removed from the ER membrane and degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) within the cytosol47. While wild type CFTR is already an inefficiently folded protein such that only 25% of the translated protein matures and progresses to the membrane, the ΔF508 folding defect is so severe that this efficiency drops below 1%48. As a result, the number of mutant channels that are present in the apical membrane of the pulmonary epithelial cells is very low and the chloride transport into the airways is deficient49. A class of CF therapeutics, called correctors, are being developed in order to overcome the maturation defect of ΔF50850. Unfortunately, because the ΔF508 mutation also causes defects in gating and decreased channel stability in the membrane51, correctors alone are unlikely to rescue epithelial chloride conductance. For this reason, potentiator molecules that fix the gating defect are also being developed50.

3.1.2. PHHI: disrupted KATP trafficking

KATP channels expressed in the beta cells of the islets of langerhans play a central role in coupling blood glucose levels and insulin release. These channels are formed by the coassembly of 4 pore-forming Kir6.2 subunits (encoded by the KCNJ11 gene) and 4 sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1) subunits52–55. Members of the Kir family, including Kir6.2, are inwardly rectifying potassium channels whose typical function is to stabilize the resting membrane potential near the potassium equilibrium potential. Elevated blood glucose levels result in corresponding increases in the beta cell glucose concentration, which leads to increased ATP and decreased ADP levels. Because ATP inhibits and ADP activates KATP channels, the change in nucleotide concentrations closes the KATP channels56, leading to a depolarization of the beta cell membrane, and therefore an increased bursting activity, calcium entry, and insulin secretion57.

Loss of function mutations in either the Kir6.258 or the SUR159 subunit are associated with Persistent Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia of Infancy (PHHI). PHHI presents early in life with severe hypoglycemia that can cause seizures, brain-damage and death. In KATP associated PHHI, loss of KATP currents causes hyperexcitability of the beta cells; and therefore, insulin secretion from the pancreas occurs despite severe hypoglycemia60. In other words, despite the dangerously low glucose levels, blood insulin levels remain high due to constitutive secretion by the pancreatic beta cells. Treatment can require total pancreactomy, which can lead to diabetes and digestive problems due to deficiencies in insulin and pancreatic enzymes respectively. Normally Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits do not traffic to the cell surface on their own, and are retained in the ER when expressed alone.

A key determinant of ER retention has been identified as the RKR motif, which is present in both the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits. Removal of the RKR motif by truncation of the Kir6.2 C-terminus or mutation to AAA allows Kir6.2 to be expressed to the membrane without SUR1; likewise, AAA mutation of the SUR1 RKR motif permits expression of SUR1 subunits alone to reach the membrane61. Proper trafficking of the wt subunits appears to require 1:1 coassembly of Kir6.2 and Sur1 subunits52–55 in order to hide the RKR motifs on each of the subunits, because the exposure of even a single RKR motif results in accumulation of the channels in the ER61. In addition to the RKR motif, a forward trafficking motif has been identified in the C terminus of SUR1 that greatly decreases the surface expression of KATP when mutated62–63. Many mutations that have been associated with PHHI can cause defective trafficking of KATP64–65, resulting in too few of these channels in the membrane and loss of the potassium current that would normally prevent insulin release in the setting of low blood glucose by stabilizing the beta cell membrane at the resting potential. Some of these mutations (such as (R1437Q(23)X in SUR166) may disrupt trafficking due to their truncation of the forward trafficking signal in the SUR1 C terminus. Others (such as H259R in Kir6.263 or ΔF138867 or L1544P in SUR168) may unmask the RKR ER retention signal as trafficking for these mutations can be partially rescued in heterologous expression systems by the ablation of the RKR motifs. Not all PHHI associated mutations demonstrate a trafficking defect. Some mutations can affect gating of channels in the membrane instead of, or in addition to, trafficking63,67,69–71. Distinguishing between these molecular mechanisms of decreased KATP current is of therapeutic interest as drug with actions that are limited to the surface membrane are unlikely to be beneficial to patients with trafficking deficient channels that do not reach the membrane to be opened by the drug.

3.1.3. Liddle’s syndrome: defective channel turnover

The Epithelial Sodium Channels (ENaCs) are expressed in certain epithelial tissues including in the distal nephron, the lungs, the colon and sweat glands72–73. ENaCs are Na+ selective channels that are blocked by the diuretic drug amiloride and are thought to be formed by the tetrameric coassembly of related α, β, and γ subunits (2α:1β:1γ)74–76. This model remains controversial with evidence suggesting a possible 9 subunit structure77, the possible involvement of a fourth (δ) subunit78–79, and the crystal structure of a related channel displaying a trimeric architecture80. In the distal nephron, ENaCs expressed in the principal cells of the collecting tubules72 play an important role in the regulation of blood pressure. There is a large driving force for filtered Na+ ions to be reabsorbed across the apical membrane of the principal cell in the collecting tubules due to the active pumping of Na+ across the basal membrane by the Na/K pump. However, under basal conditions the Na+ permeability of the apical membrane is low and the Na+ ions remain in the filtrate and are excreted along with water in the urine. A drop in blood pressure activates the renin-angiotensin system leading to increased secretion of the hormone aldosterone by the adrenal medulla. Aldosterone acts at the principal cell to upregulate ENaC channel expression resulting in increased membrane Na+ permeability, the reclamation of filtered Na+, and the reabsorption of water that follows the osmotic gradient generated by the Na+ reuptake81. Through these mechanisms the extracellular volume can be decreased or increased in response to changes in blood pressure to maintain homeostasis.

Liddle’s syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease that causes severe and early onset hypertension despite low plasma renin and aldosterone levels and is associated with mutations of ENaC82–86. Liddle’s syndrome associated mutations are located in the cytoplasmic C terminus of the ENaC subunits, disrupt or delete a conserved protein motif (the PY motif), and cause increased number of ENaC channels in the apical membrane82– 84,87–92. In wild type channels the PY motif interacts with the WW domain on another protein, Nedd4-293. Nedd4-2 is a ubiquitin ligase (E3) and catalyzes the final step of an enzymatic cascade that results in the covalent linkage of ubiquitin to lysine residues94 in the ENaC N terminus. Ubiquitination of membrane proteins95, including ENaC96, signals for reuptake from the surface membrane and targeting to the lysosome for eventual degradation. In Liddle’s Syndrome ubiquitination of mutant ENaC channels by Nedd4-2 is lost due to disruption of the protein-protein interaction, resulting in an enhanced stability of ENaC channels in the membrane97 and increased Na+ permeability even under conditions of low aldosterone. In heterologous expression mutation of the ubiquitinated lysines, or overexpression of an enzymatically inactive Nedd4 mutant increases the number of expressed ENaC channels in the surface membrane with a corresponding increase in Na+ conductance96,98. In patients with Liddle’s syndrome the increased number of ENaC channels in the apical membranes of principal cells in the collecting ducts leads to pathological reabsorption of Na+ and water, generating volume overload and severe hypertension as seen in a mouse model carrying a Liddle Syndrome mutation when fed a high salt diet99. Treatment for Liddle’s syndrome involves a low salt diet and an ENaC blocking drug, such as amiloride100.

3.2.1. APA and FH-3: loss of ion selectivity

Primary aldosteronism (PAL) is a form of hypertension that is caused by constitutive secretion of the hormone aldosterone by the adrenal glands. Normally low intravascular volume leads to aldosterone production through the renin-angiotensin signaling pathway, and aldosterone acts at the kidneys to increase Na+ and water retention leading to a compensatory increase in volume (see section 3.1.3). In PAL, aldosterone is continuously produced by the adrenal glomerulosa cells despite low plasma renin/angiotensin, hypokalemia and hypertension101. Patients suffer from hypertension that is resistant to treatment, hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis (aldosterone dependent Na+ reabsorption drives K+ and H+ excretion). Severe hypertension puts these patients at risk for cardiovascular events such as stroke and myocardial infarction102. PAL can be caused by different mechanisms, a frequent cause is an adrenal producing adenoma (APA)103, a benign adrenal tumor that occurs sporadically. More rare are inherited mutations that cause hyperplasia and increased aldosterone production in the Familial Hyperaldosteronism (FH). Recently, mutations in the KCNJ5 gene encoding an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir3.4 or GIRK4) have been found to be a common cause of APA (G151R, T158A, L168R)104 and present in five FH type-3 kindred (G151R, G151E, T158A)104–105. All of these mutations are located either directly within the selectivity filter or play a likely role in the stabilization of the filter structure according to the recent structure of the related Kir2.2 channel106. The functional effect of all of these mutations is a loss of potassium selectivity giving rise to significant Na+ current and depolarization of the cell membrane104–105. In glomerulosa cells, membrane depolarization opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, providing calcium influx that triggers aldosterone production107. Expression of the APA associated T158A mutation in an adrenal carcinoma cell line, to simulate in-vivo cellular conditions, caused increased aldosterone production and increased expression of genes involved in the production of aldosterone108. Further, these effects were shown to be dependent on the influx of Na+, Ca2+, and on calmodulin108 supporting the proposed mechanism that the mutant Kir3.4 mediates constitutive aldosterone secretion through calcium dependent pathways104. It was also proposed that the increased Ca2+ influx triggers an increase in cell mass underlying the hyperplasia present in APA and FH104. However, this hyperplastic effect has not been recapitulated in vitro indicating108, perhaps, that some other factor is required or that the cell growth is not simply a direct effect of depolarization and Ca2+ influx. To this point, two mutations of the same position (G151E, G151R) cause different cellular and clinical phenotypes. G151E generates a larger abnormal Na+ current and is associated with milder disease and has not been found in APA, while G151R generates a smaller Na+ influx but is associated with more severe disease. These findings are resolved by the robust cytotoxicity caused by G151E, but not G151R. The constitutive aldosterone production by G151E expressing cells is blunted by increased rates of cell death showing why the milder disease phenotype and absence of adenomas expressing G151E104. These mutations illustrate that there is not a simple relationship between membrane depolarization and cellular mass. Treatment of PAL depends on the underlying pathology. While APA tumors are well defined and conservative surgical excision is effective, FH is caused by germline mutations and therefore is associated with diffuse adrenal gland dysfunction. For FH patients treatment often involves a more severe approach, bilateral adrenalectomy103. Perhaps in the future, identification of patients with KCNJ5 mutations will allow for effective control of hypertension with less drastic treatment such as a blocker targeting the adrenal Kir3.4 channel.

3.2.2. SVD: another case of lost ion selectivity

Snowflake vitreoretinal degeneration (SVD) is an inherited ocular disease characterized by the degeneration of the vitreous, retinal and corneal abnormalities, and crystal deposits in the retina that resemble snowflakes. Patients with SVD experience early onset cataracts and carry a moderate risk of retinal detachment, but usually retain visual acuity109. Mutation of the KCNJ13 gene on chromosome 2 has been associated with SVD110–111. KCNJ13 encodes an inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir7.1, with a low single channel conductance and low sensitivity to extracellular K+ and Ba+ compared to other inward rectifier K+ channels112–113. Kir7.1 has been detected in rat and bovine retinal pigmented epithelium where it is thought to play a role in K+ transport114–115, and has also been detected in the human retina and retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE)111. The SVD associated Kir7.1 mutation, R162W, causes a loss of K+ selectivity resulting in a current that reverses at −9mV (as compared to the equilibrium potential of K+ at −90mV) under the experimental ionic conditions used111. This result indicated that the R162W Kir7.1 in the retina and the RPE would generate an inward depolarizing cation current rather than the outward K+ current of the wild type channel. The mechanism of how these defects eventually lead to the pathology of SVD remains unclear. Interestingly, R162W is not located in or near the selectivity filter like the APA associated KCNJ5 mutations (see section 3.2.1) instead R162W is located at the membrane-cytoplasm interface in a putative binding site for the regulatory lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). How a mutation at this location in the channel structure leads to a loss of selectivity is unclear and remains to be studied.

3.3. Channel gating (Po)

An increase in ion channel open probability (Po) in response to an external stimulus is called activation (Fig. 2 shows an example of activation in response to a voltage stimulus). Conversely, removal of the stimulus causes a reduction in open probability, known as deactivation. Some channels have additional gating processes that reduce open probability when the stimulus is still present, which is called channel inactivation. In the case of the voltage-gated Na+ channel in excitable cells, inactivation occurs several milliseconds after activation to produce a quick spike in current after a change to positive potential (Fig. 5D). The structural motifs for activation and inactivation, i.e., the activation gate and inactivation gate are usually distinct and located separately in the channel protein.

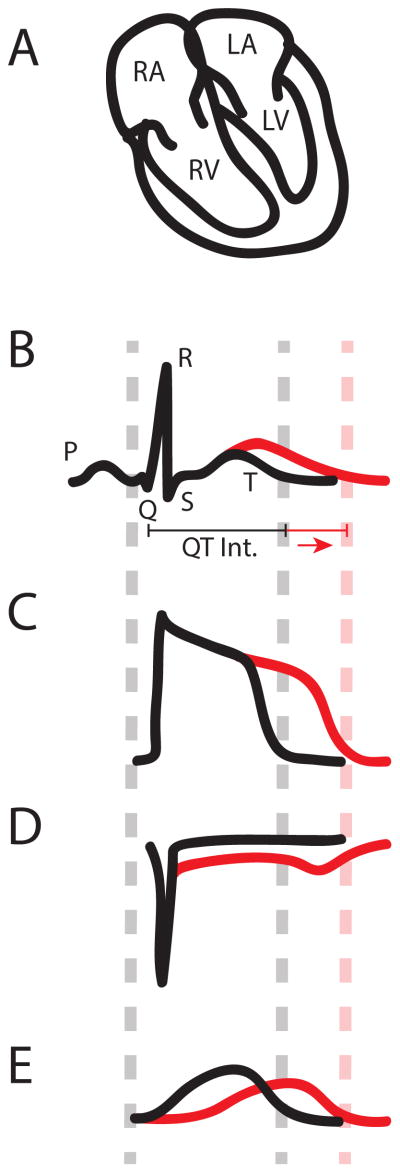

Figure 5.

QT interval and action potential (AP) prolongation caused by genetic mutations. The ECG measures the electrical activity of the heart reflected on the body surface, and the waveform of ECG correlates with electrical depolarization and repolarization of the cardiac muscle in various chambers (A, B). The first upward deflection in panel B (P wave) corresponds to activation of the upper heart chambers, the left and right atria (LA and RA, respectively), which collect blood that is returning from the body (RA) and the lungs (LA). The prominent spike formed by the Q, R, and S points is linked to excitation of the massive lower chambers, the left and right ventricles (LV and RV, respectively). The magnitude of the QRS complex is a consequence of the larger ventricular muscle mass, which is needed to generate the force that pushes blood through the body (LV) and the lungs (RV). Finally, the T wave occurs when the ventricles return to an electrical resting state. Consequently, we would expect that a prolonged QT interval is caused by an increase in the time that the ventricles remain in an electrically excited state. The individual cells in the myocardium, myocytes, each generate an action potential (AP) (C) that is responsible for excitation. Therefore, the QT interval (B) corresponds to the duration of the ventricular AP (C), implying that any change in AP duration (APD) will affect the QT interval. APD is determined by a delicate balance of inward and outward ionic currents. The morphology of the AP (C) is the consequence of positively charged Na+, Ca2+ and K+ ions entering and exiting the myocyte. For example, as the membrane potential (Vm) rises from its resting state, caused by the excitation of a neighboring myocytes, Na+ channels open and positively charged Na+ ions enter the cell (D). This inward sodium current (INa) causes Vm to rise quickly. Once Vm is elevated by INa, voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels open and bring in a sustained inward Ca2+ flux, ICa,L 221 (not shown). It is this influx of Ca2+ that signals contraction of the myocyte222. The sustained ICa,L supports the AP plateau, which continues until the K+ channels open to generate repolarizing outward current (E). Throughout the AP a small inward Na+ current persists and is enhanced towared the end of the AP when channels begin to recover from inactivation, but are not deactivated yet (window current). In ventricular myocytes there are two major repolarizing K+ currents, one rapid component (IKr) and one slow (IKs)223. The IKr α-subunit, Kv11.1, is encoded by the KCNH2 (aka HERG) gene224 and the IKs α-subunit, Kv7.1, is encoded by the KCNQ1 (aka KvLQT1) gene143–144. Once the outward K+ flux overwhelms the inward Ca2+ flux, the myocyte returns to its resting state. APD is therefore determined by the balance of inward and outward ion fluxes. Increasing inward currents (D) or reducing outward currents (E) will prolong APD (C) and therefore the QT interval (B).

Mutations that affect activation, deactivation or inactivation can lead to channelopathies. We describe two mutations that directly modify channel gating to cause disease. The first adversely affects channel activation while the second impairs channel inactivation. Both mutations result in the Long QT Syndrome (LQTS), which is described below.

Patients with LQTS are typically identified after they or family members experience dizziness, heart palpitations, or even an episode of ventricular fibrillation (VF)116. In terms of dizziness the symptom is caused by a lack of adequate blood circulation. Palpitations occur if the heart is not generating its rhythm normally, but instead is excited via triggered activity or a reentrant arrhythmia- when normal heart excitation does not self-terminate and pathologically re-excites previously excited tissue in an unregulated fashion. The rapid heartbeat that ensues is felt as palpitations. If a patient experiences VF, death can occur if the patient is not quickly resuscitated, usually via a strong electrical shock, known as defibrillation. A subsequent visit to a physician usually results in the detection, via electrocardiogram, of a prolonged QT interval, the time duration between the Q and T points on the electrocardiogram (ECG) (Fig. 5)116–117.

The QT interval, as a reflection of ventricular excitation is dependent on ventricular myocyte action potential duration (APD). Since APD is linked to the magnitude of the inward and outward currents, any change in these will alter the QT interval. Figs. 5D and 5E show examples where either inward Na+ current, INa, or outward K+, IK, is increased or decreased, respectively to prolong APD and therefore the QT interval.

AP prolongation is pro-arrhythmic because of its effect on the L-type Ca2+ current, ICa,L. As the membrane potential repolarizes at the end of the AP, ICa,L recovers from both voltage-dependent inactivation, as Vm becomes more negative, and Ca2+-dependent inactivation, as Ca2+ is removed from the cytoplasm into the sarcoplasmic reticulum by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA)118–119 and out into the extracellular space by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger120–121. Normally, deactivation occurs soon thereafter, and inward Ca2+ current stops. However, when the action potential is prolonged, ICa,L can reactivate after recovering from inactivation instead of deactivating. This reactivation causes an increase in Vm that may inappropriately excite adjacent tissue and trigger an arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.

So far mutations in 13 genes have been associated with LQTS. Many of these genes encode cardiac ion channels122–128, three encode auxiliary beta-subunits129–131, while the other four are involved in the organization of ion channels to the macromolecular complexes and tethering to the cytoskeleton132–135. Mutations in three genes are responsible for the majority of LQT mutations – a sodium channel (SCN5a) gene128 which encodes the cardiac Na+ channel, Nav1.5, and two potassium channel (KCNQ1 and KCNH2) genes125,127, which encode the Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 channels respectively. As expected, additional inward Na+ current from SCN5a mutations126,136 and reduced outward K+ current from KCNQ1 and KCNH2 mutations cause the LQTS. However, the mechanism of how these mutations alter currents of these channels varies. For instance, hundreds of mutations in KCNQ1 alone have been associated with LQTS137; some mutations alter channel gating138–139, some alter channel expression140, and yet some alter posttranslational modification of these channels141, while the mechanism of most of these mutations in altering Kv7.1 currents is still unknown.

3.3.1. LQT1: defective channel activation

LQTS type 1 (LQT1) results from mutations to KCNQ1 gene127, which encodes a voltage-gated K+ channel (Kv7.1) α-subunit that forms functional tetrameric channels. The α-subunit contains six transmembrane segments (S1–S6). S1–S4 form a voltage-sensing domain, while S5 and S6 form the pore. In particular, S4 carries several positively charged residues (Arg and Lys) that move when the transmembrane potential changes to open and close the channel (see Fig. 2). The native cardiac current, termed the slow-delayed rectifier current (IKs), is carried by a channel that includes the α-subunit (Kv7.1) as well as a variable number of modulatory β-subunits (KCNE1) with a single-transmembrane segment142–146. Mutations in the KCNE1 gene can also cause LQTS (LQT5)130. Reduction of IKs can happen through a variety of mechanisms. The case of E160K is unique however because it involves a charge switching mutation in a transmembrane helix of the voltage-sensing domain, S2.

For many years, it has been posited that negative charges within the voltage-sensing domain transmembrane spanning domains stabilize the S4 positive charges within the hydrophobic membrane interior147. This hypothesis was later supported with charge neutralizing mutagenesis148–149 and with the recent crystal structure of Kv1.2/2.1 chimera channel showing salt bridges formed between the positive charges in S4 and the negative charges in S2 and S3150. All three negative charges found in the Kv1.2/2.1 S2 and S3 (Fig. 2) are conserved in Kv7.1138. The E160K mutation switches the negative charge near the extracellular surface of the voltage-sensing domain in S2 to a positive charge. We hypothesized that the addition of positive charge at this site would impair voltage sensor movement, locking it in a particular conformation. Subsequent experiments showed that progressively adding charge (E160Q, E160A, and E160K) resulted in slowing of channel activation that was proportional to the charge added138. Indeed, E160K showed no current whatsoever. Subsequent biochemical and electrophysiology studies showed that this channel is able to traffic to the surface of the cell, but its voltage-sensing domain is unable to make the transition from the resting to activated state139. Thus, the E160K mutation, preventing channel activation, removes repolarizing current carried by IKs and causes pro-arrhythmic prolongation of the ventricular AP as in Fig. 5E.

3.3.2. LQT3: defective channel inactivation

In LQTS type 3 (LQT3) the cardiac sodium channel gene (SCN5a) carries a mutation(s) that causes QT interval prolongation. After voltage-gated Na+ channels open to initiate the AP, they typically inactivate and do not play a major role for the duration of the AP. Structurally, the voltage-gated Na+ channel is related to but different from the voltage-gated K+ channel. Instead of being formed by tetramers of identical subunits, functional Na+ channels can be formed by a large monomer that has four unique, but homologous domains (DI–DIV)151, each of which is equivalent to a K+ channel α-subunit. The differences in each domain and the linkers between them allow each to carry out a unique function such as activation (DI, DII and DIII)152, conferring voltage dependence to inactivation (DIV)153–154, and mediating inactivation (DIII–DIV linker)155. As with a voltage-gated K+ channel subunit, each domain contains 4 transmembrane segments (S1–S4) that form a voltage- sensor and 2 segments (S5–S6) that contribute to the pore. Also like voltage-gated K+ channels, the outward movement of the S4 segments causes channel activation. Inactivation is caused by a hydrophobic intracellular motif (IFM) that resides in the DIII–DIV linker156. When the IFM motif binds near the channel pore157–158, the channel can no longer conduct current. Any perturbation to the channel that disrupts this inactivation process results in unwanted inward current, which can prolong the APD. One mechanism of LQT3 is incomplete inactivation that enhances a persistent pedestal current that lasts throughout the AP and pro-arrythmically prolongs APD. The first documented mutation to display this behavior was ΔKPQ, which removes three residues from the inactivation-linked DIII–DIV linker (Fig. 5D)126.

While ΔKPQ quite dramatically affects INa, other mutations are much more subtle. For example, E1295K, which resides near the DIII S4 segment, causes a shift in the voltage dependence of both inactivation and deactivation towards more positive potentials159. The consequence is a shift in the so called “window current”160. The window current refers to a current that occurs at when Vm is low enough that the channel is not fully inactivated, but still high enough for partial channel activation. The result is a fraction of the channels remaining open. In Fig. 5D the inward deflection at the end of the AP in INa is a consequence of the window current. For E1295K Na+ channels, the window current is shifted so that it occurs at a more depolarized potential. The result is an inward current during the AP that overlaps with ICa,L window current (described above), which can cause ICa,L reactivation and dangerous triggered activity.

Finally, and even more subtly, changes in the gating kinetics can cause a non-equilibrium disruption. In this case, the steady-state inactivation and deactivation occupancies are unaffected. Instead the timing of recovery from inactivation and deactivation is altered. For example, In this case, either the rate of recovery from inactivation may be faster so that channels recover from inactivation much more rapidly than they deactivate.

Conversely, if the rate of deactivation is slowed, channels will also recover faster than they deactivate and remain open for a longer period of time. In the presence of the I1768V mutation, which resides in the C-terminus after the DIV S6 segment, mutant channels recover from inactivation much more quickly than in wild type channels161–162. Consequently, channels accumulate in the open state because recovery from inactivation is much faster than the channel deactivation. The increase in open probability due to this gating imbalance ttresults in enhanced pro-arrhythmic, depolarizing Na+ current.

4. Concluding remarks

In recent history, a wide variety of genetic defects that cause ion channel dysfunction have been linked to human diseases. Since ion channels exist in the membranes of all cell types and play important roles in a variety of physiological processes, channelopathies have been found in every organ system. In the central nervous system ion channels have been linked to many diseases such, but not limited to, ataxias, paralyses, epilepsies, and deafness indicative of the roles of ion channels in the initiation and coordination of movement, sensory perception, and encoding and processing of information. These channelopathies in the nervous system often involve complex function of neural networks and it is difficult to trace the symptoms back to an abnormality of a single channel property. In this review we have presented only examples of peripheral channelopathies as the simpler tissue networks and organization make connecting the molecular, cellular, tissue and organ scales more approachable.

There is a great diversity of ion channels that are selective to various ions and are activated by a vast array of physiological stimuli. Aside from Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Cl− channels that are selectively permeant to these major ions inside and outside of cells, channels that are selective for protons22–23 or permeate other metal ions such as iron (Fe2+) 163, zinc (Zn2+)164 and magnesium (Mg2+)165 or selectively permeate water molecules166–167 are also essential in important physiological processes. The physical and chemical changes that accompany these physiological processes serve as signals to open and close ion channels; these signals include membrane potential, heat168, mechanical stretch169, extracellular neurotransmitters170, and intracellular cell signaling molecules such as G-proteins 171, cyclic nucleotides172–173, phospholipids174–176, and Ca2+177–179.

Much work has been done to understand how channels are altered and how these alterations cause disease phenotypes. Despite the diversity of ion channels and the wide variety of channelopathies, the function of ion channels is described by a simple equation, Ichannel = N * gchannel * P0 * (Vm − Vr), which relates the magnitude of ionic current to the number of channels, how much current a single channel carries, the probability of each channel being open, the ionic selectivity and the membrane potential. This elegant description of ion channel function allows a few examples presented here to show how the different components of this equation are perturbed by mutations to affect organ function. Cystic Fibrosis, Persistent Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia of Infancy and Liddle’s Syndrome are all related to changes in the number of channels(N). While the driving force, (Vm−Ve), is altered by a loss of selectivity in set of patients with Adrenal Producing Adenoma/Familial Hyperaldosteronism or Snowflake Vitreoretinal Degeneration. Po is affected by changes in gating properties- we presented two instances that result in the Long QT Syndrome. Surprisingly we were unable to identify an example of a mutation in an ion channel causing disease by altering single channel conductance. The reasons for this are unknown, but we can speculate that such instances exist unappreciated by the literature due to the difficulty associated with recognizing such a mechanism. First, recording single channel currents is technically difficult and therefore not measured in many studies. Second, if the mutation completely eliminates single channel conductance it becomes indistinguishable from a mutation that simply reduces open probability to zero. Therefore only a subtle reduction or an increase in single channel conductance could be readily linked to disease pathogenesis. Of course these more subtle changes can be difficult to detect and may not cause enough of a defect in the macroscopic current to generate symptoms.

While the gain or loss of channel function according to the above equation accounts for the cellular and higher order phenotypes, much remains to be learned regarding the molecular mechanisms that cause channel dysfunction. For example, in LQT1 why a particular mutation causes a trafficking defect, while another alters gating is only beginning to be understood. Mechanistic studies beyond the initial identification of disease-associated mutations and new advances in experimental methodology will allow us to answer some of these questions. One major push is to obtain crystal structures of the disease-linked channels, which will illuminate the structural environment in which mutations reside. For example while the Kv7.1 channel is homologous to the already solved Kv1.2 structure180, a close comparison of the sequences shows that there are many regions, including intracellular region near S4 that are clearly different. Moreover, several LQT1-linked mutations reside in this region181–183. Even less homology is observed between the Kv11.1 K+ channel and Kv1.2 K+ channels. Kv11.1 channels are linked to inherited LQT2 as well as acquired LQT, which is caused by many common drugs including antibiotics, anti- histamines, and anti-psychotics184. Another recent technique is voltage clamp fluorometry185–187, which utilizes fluorescence to correlate protein motion with ionic current. One commonly labeled location is the extracellular S3–S4 linker next to the S4 segment in the voltage sensing domain. When a voltage stimulus is applied, the S4 segment moves outward, and the environment around the fluor changes. These environmental changes, correlating to the S4 motion, are reflected in the magnitude of the fluorescence and measured with a sensitive detector. In the near future, this technology is likely to be applied to understanding disease mutations to identify specific gating transitions that are affected by inherited genetic defects. Finally, the cellular context is vital to understanding diseases. Often, channels introduced into heterologous expression systems display highly variable phenotypes depending on which system was chosen188. The ideal situation would be access to native human cells, which are unfortunately not often available. A recent advance in stem cell technology, induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, offers a way forward189. iPS cells are obtained initially as fibroblasts from a skin biopsy, then transformed into pluripotent stem cells hormonally. Once the stem cells are induced, they can be transformed once again into a differentiated cell such as a cardiac myocyte190. The ability to take cells from a patient that is carrying a mutation, not only allows study of the mutation in a native context, it also provides a means for assessing why some mutation carriers show a deadly phenotype while others are asymptomatic.

In this review, we have presented examples of diseases for which a single mutation within an ion channel gene segregates with disease symptoms. The study of these (often rare) monogenetic channelopathies identified new ion channels underlying various physiological currents and yielded great insight into the structure-function relationships of ion channel proteins. In some cases, the field has come full circle by providing clinically useful insight of prognostic and therapeutic value. The wide expression of ion channels in all tissue indicates that the role of ion channels in disease pathogenesis must extend beyond the identifiable monogenic channelopathies. Many human diseases cannot be attributed to a single disease-linked mutation. Instead disease such as type II diabetes191, schizophrenia192, and essential hypertension193 involve the interplay of many genes and environmental factors. Although not the primary insult, ion channel dysregulation may play important roles in the pathology associated with polygenic diseases. In our new frontier where genome wide association can be quantified, we can now begin to detect the correlation between variations in ion channel genes and these diseases194–198. As these links are made they will warrant additional investigation into the variations in the molecular properties of the identified ion channels that confer additional risk for disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (R01-HL70393 and R01-NS060706 to J.C.), A Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface (1010299 to J.R.S.), and a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (11PRE5720009 to MAZ). J.C. is the Professor of Biomedical Engineering on the Spencer T. Olin Endowment.

Biographies

Mark A Zaydman is an MD/PhD student at Washington University in St Louis studying the mechanisms through which PIP2 potentiates gating of Kv7 channels by membrane voltage. By combining training in biophysics, medicine and biomedical engineering he aims to study ion channels from basic molecular mechanisms up to cellular and organ systems.

Jonathan Silva is an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the Washington University School of Engineering in St. Louis, MO. His group is interested in understanding how molecular interactions propagate across time and spatial scales to affect the cardiac rhythm.

Jianmin Cui is the Professor of Biomedical Engineering on the Spencer T. Olin Endowment at Washington University in St. Louis. He received a Ph.D. in Physiology and Biophysics from State University of New York at Stony Brook and a post-doctoral training at Stanford University. He was an assistant professor of Biomedical Engineering at Case Western Reserve University before moving to St. Louis. His research interests are on membrane permeation to ions, drugs and genes, including the molecular mechanisms of ion channel function and ultrasound-mediated drug/gene delivery. Dr. Cui is a recipient of the Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association.

References

- 1.Armstrong CM, Hille B. Neuron. 1998;20:371. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J, Ellinor PT, Sather WA, Zhang JF, Tsien RW. Nature. 1993;366:158. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2001;414:43. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKinnon R. Angewandte Chemie. 2004;43:4265. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payandeh J, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. Nature. 2011;475:353. doi: 10.1038/nature10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu H, Shen R, Guo W. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piasta KN, Theobald DLM, Christopher J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:421. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morais-Cabral JH, Zhou Y, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2001;414:37. doi: 10.1038/35102000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong CM. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:413. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmgren M, Smith PL, Yellen G. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:527. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Holmgren M, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Neuron. 1997;19:175. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perozo E, Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Science. 1999;285:73. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.del Camino D, Yellen G. Neuron. 2001;32:649. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2002;417:523. doi: 10.1038/417523a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothberg BS, Shin KS, Phale PS, Yellen G. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:83. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothberg BS, Shin KS, Yellen G. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:501. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster SM, del Camino D, Dekker JP, Yellen G. Nature. 2004;428:864. doi: 10.1038/nature02468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Zhao Y, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Roux B, Perozo E. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Perozo E. Nature. 2010;466:203. doi: 10.1038/nature09153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uysal S, Cuello LG, Cortes DM, Koide S, Kossiakoff AA, Perozo E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105112108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki M, Takagi M, Okamura Y. Science. 2006;312:589. doi: 10.1126/science.1122352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsey IS, Moran MM, Chong JA, Clapham DE. Nature. 2006;440:1213. doi: 10.1038/nature04700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neher E, Sakmann B. Nature. 1976;260:799. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman ML, VanDongen HMA, VanDongen AMJ. Biophys J. 1997;72:708. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78707-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend C, Hartmann HA, Horn R. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:11. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Townsend C, Horn R. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malmivuo J, Plonsey R. Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields. Oxford University Press; New York, New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodie C, Bak A, Sampson SR. Brain Res. 1985;336:384. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90674-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heimeshoff M, Hollmeyer H, Schreyögg J, Tiemann O, Staab D. PharmacoEconomics. 2012;30:763. doi: 10.2165/11588870-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frizzell RA, Rechkemmer G, Shoemaker RL. Science. 1986;233:558. doi: 10.1126/science.2425436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welsh MJ. Science. 1986;232:1648. doi: 10.1126/science.2424085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M, McCann JD, Liedtke CM, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Welsh MJ. Nature. 1988;331:358. doi: 10.1038/331358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC. Science. 1989;245:1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL. Science. 1989;245:1066. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N. Science. 1989;245:1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2772657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Souza DW, Paul S, Mulligan RC, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Cell. 1991;253:202. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson MP, Berger HA, Rich DP, Gregory RJ, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Cell. 1991;67:775. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bear CE, Li CH, Kartner N, Bridges RJ, Jensen TJ, Ramjeesingh M, Riordan JR. Cell. 1992;68:809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang TC, Nagel G, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linsdell P, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW. Biophys J. 2000;78:2973. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O’Riordan CR, Smith AE. Cell. 1990;63:827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.French PJ, van Doorninck JH, Peters RH, Verbeek E, Ameen NA, Marino CR, de Jonge HR, Bijman J, Scholte BJ. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1304. doi: 10.1172/JCI118917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Nature. 1992;358:761. doi: 10.1038/358761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang F, Kartner N, Lukacs GL. Nature. 1998;5:180. doi: 10.1038/nsb0398-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lukacs GL, Mohamed A, Kartner N, Chang X, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. EMBO J. 1994;13:6076. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Cell. 1995;83:121. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward CL, Kopito RR. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rich DP, Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Cheng SH, Paul S, Jefferson DM, McCann JD, Klinger KW, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Nature. 1990;347:358. doi: 10.1038/347358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai Z-w, Liu J, Li H-y, Sheppard DN. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:693. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lukacs G, Chang X, Bear C, Kartner N, Mohamed A, Riordan J, Grinstein S. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Science. 1995;270:1166. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shyng S, Nichols CG. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:655. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clement JP, IV, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Neuron. 1997;18:827. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Seino S. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:232. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nichols CG, Shyng SL, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Clement JP, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Permutt MA, Bryan J. Science. 1996;272:1785. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huopio H, Shyng SL, Otonkoski T, Nichols CG. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:E207. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00047.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas P, Ye Y, Lightner E. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1809. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.11.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas PM, Cote GJ, Wohllk N, Haddad B, Mathew PM, Rabl W, Aguilar-Bryan L, Gagel RF, Bryan J. Science. 1995;268:426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kane C, Shepherd RM, Squires PE, Johnson PR, James RF, Milla PJ, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ, Dunne MJ. Nat Med (N Y, NY, U S) 1996;2:1344. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY. Neuron. 1999;22:537. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma N, Crane A, Clement JP, Gonzalez G, Babenko AP, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marthinet E, Bloc A, Oka Y, Tanizawa Y, Wehrle-Haller B, Bancila V, Dubuis J, Philippe J, Schwitzgebel V. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5401. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partridge CJ, Beech D, Sivaprasadarao A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan F-F, Lin Y-W, MacMullen C, Ganguly A, Stanley CA, Shyng S-L. Diabetes. 2007;56:2339. doi: 10.2337/db07-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dunne MJ, Kane C, Shepherd RM, Sanchez JA, James RF, Johnson PR, Aynsley-Green A, Lu S, Clement JP, Lindley KJ, Seino S, Aguilar-Bryan L. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:703. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cartier EA, Conti LR, Vandenberg CA, Shyng S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051499698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taschenberger G, Mougey A, Shen S, Lester L, LaFranchi S, Shyng SL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cartier EA, Shen S, Shyng S. J Biol Chem. 2002;278:7081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shyng SL, Ferrigni T, Shepard JB, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Permutt MA, Nichols CG. Diabetes. 1998;47:1145. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.7.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan KW, Zhang H, Logothetis DE. EMBO J. 2003;22:3833. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duc C, Farman N, Canessa CM, Bonvalet JP, Rossier BC. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1907. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Renard S, Voilley N, Bassilana F, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Pfluegers Arch. 1995;430:299. doi: 10.1007/BF00373903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Firsov D, Gautschi I, Merillat AM, Rossier BC, Schild L. EMBO J. 1998;17:344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berdiev BK, Karlson KH, Jovov B, Ripoll PJ, Morris R, Loffing-Cueni D, Halpin P, Stanton BA, Kleyman TR, Ismailov II. Biophys J. 1998;75:2292. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77673-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kosari F, Sheng S, Li J, Mak DO, Foskett JK, Kleyman TR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Snyder PM, Cheng C, Prince LS, Rogers JC, Welsh MJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Voilley N, Lazdunski M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bangel-Ruland N, Sobczak K, Christmann T, Kentrup D, Langhorst H, Kusche-Vihrog K, Weber WM. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:498. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0053OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Nature. 2007;449:316. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fuller PJ, Young MJ. Hypertension. 2005;46:1227. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000193502.77417.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shimkets RA, Warnock DG, Bositis CM, Nelson-Williams C, Hansson JH, Schambelan M, Gill JR, Ulick S, Milora RV, Findling JW. Cell. 1994;79:407. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hansson JH, Nelson-Williams C, Suzuki H, Schild L, Shimkets R, Lu Y, Canessa C, Iwasaki T, Rossier B, Lifton RP. Nat Genet. 1995;11:76. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hansson JH, Schild L, Lu Y, Wilson TA, Gautschi I, Shimkets R, Nelson-Williams C, Rossier BC, Lifton RP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Cell. 2001;104:545. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liddle GW, Bledsoe T, CWS Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1963;76:199. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Corvol P. J Endocrinol Invest. 1995;18:592. doi: 10.1007/BF03349775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Snyder PM, Price MP, McDonald FJ, Adams CM, Volk KA, Zeiher BG, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ. Cell. 1995;83:969. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schild L, Lu Y, Gautschi I, Schneeberger E, Lifton RP, Rossier BC. EMBO J. 1996;15:2381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tamura H, Schild L, Enomoto N, Matsui N, Marumo F, Rossier BC. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1780. doi: 10.1172/JCI118606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Firsov D, Schild L, Gautschi I, Merillat AM, Schneeberger E, Rossier BC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inoue J, Iwaoka T, Tokunaga H, Takamune K, Naomi S, Araki M, Takahama K, Yamaguchi K, Tomita K. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2210. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Staub O, Dho S, Henry P, Correa J, Ishikawa T, McGlade J, Rotin D. EMBO J. 1996;15:2371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ciechanover A. Cell. 1994;79:13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacGurn JA, Hsu P-C, Emr SD. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:231. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060210-093619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Staub O, Gautschi I, Ishikawa T, Breitschopf K, Ciechanover A, Schild L, Rotin D. EMBO J. 1997;16:6325. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu C, Pribanic S, Debonneville A, Jiang C, Rotin D. 2007;8:1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goulet CC, Volk KA, Adams CM, Prince LS, Stokes JB, Snyder PM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.30012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pradervand S, Wang Q, Burnier M, Beermann F, Horisberger JD, Hummler E, Rossier BC. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2527. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rotin D. BMC Biochem. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Clark D, 3rd, Ahmed MI, Calhoun DA. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:318. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Milliez P, Girerd X, Plouin P-F, Blacher J, Safar ME, Mourad J-J. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mulatero P, Stowasser M, Loh K-C, Fardella CE, Gordon RD, Mosso L, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Veglio F, Young WF. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]