Abstract

Tumor suppressor p53 is critical to suppress all types of human cancers, including breast cancers. The p53 gene is somatically mutated in over half of all human cancers. The majority of the p53 mutations are missense mutations, leading to the expression of the full-length p53 mutants. Several hotspot mutations, including R175H, are frequently detected in human breast cancers. P53 cancer mutants not only lose tumor suppression activity, but more problematically, gain new oncogenic activities. Despite correlation of the expression of p53 cancer mutants and the poor prognosis of human breast cancer patients, the roles of p53 cancer mutants in promoting breast cancer remain unclear. We employed the humanized p53 cancer mutant knock-in (R175H) mice and MMTV-Wnt-1 transgenic (mWnt-1) mice to specifically address the gain of function of R175H in promoting breast cancer. While both R175H/R175HmWnt-1(R175HmWnt-1) and p53−/−mWnt-1 mice died from mammary cancers at the same kinetics, which was much earlier than mWnt-1 mice, most of the R175HmWnt-1 mice developed multiple mammary tumors per mouse, whereas p53−/−mWnt-1 and mWnt-1 mice mostly developed one tumor per mouse. The multiple mammary tumors arose in the same R175HmWnt-1 mouse exhibited different histological characters. Moreover, R175H gain-of-function mutant expands the mammary epithelial stem cells (MESCs) that give rise to the mammary tumors. Since ATM suppresses the expansion of MESCs, the inactivation of ATM by R175H in mammary epithelial cells could contribute to the expansion of MESCs in R175HmWnt-1 mice. These findings provide the basis for R175H to promote the initiation of breast cancer by expanding MESCs.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women worldwide (1, 2). The tumor suppressor p53 is the most commonly altered gene in human breast cancer (3). The importance of p53 in preventing breast cancer was also illustrated by genetically engineered mice. Conditional inactivation of p53 in mouse mammary epithelial cells leads mammary tumors with a high rate of metastasis (4). Deficiency of p53 promotes chromosomal instability and accelerates mammary tumorigenesis in Wnt-1 transgenic mice (5).

P53 is a transcription factor that regulates genes critical for cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and cell senescence to maintain genome stability(6). In cancer cells, its function can be compromised by various mechanisms: mutations of Tp53, alteration of p53 regulators, alteration of p53 target genes (7). Interestingly, the proportion of missense mutations in p53 is higher than that seen in other tumor suppressor genes, suggesting that expression of p53 mutants may confer selective advantage over and above loss of wild-type function(8).

Accumulating data have shown that R175H mutation, a hotspot mutation found in various human cancers including breast cancer, have lost wild type p53-dependent tumor suppression activity, and more problematically, acquired new oncogenic properties. For example, when R175H is overexpressed in a nontransformed cell line lacking p53, it promotes tumorigenesis in immunodeficient mice, while the parental cell line does not (9). Transgenic mice overexpressing R175H in epithelial cells exhibit an increased susceptibility to chemical carcinogenesis with faster tumor development when compared to mice lacking p53 (10, 11). To investigate the function of R175H in promoting cancer in a physiological context, we recently established the humanized R175H knock-in mice (12). R175H/R175H mice develop tumor with similar kinetics as p53−/− mice but with a more complex tumor spectrum, indicating the gain-of-function of R175H in tumorigenesis. In addition, R175H shares a common gain of function with other common p53 cancer mutants such as R248W in inactivating ATM function in mouse fibroblasts and thymocytes (12, 13).

Despite the convincing evidence implicating gain-of-function of R175H in breast neoplasia, the function of R175H in the development and progression of breast cancer remains unknown. Most R175H/R175H mice died of lymphomas, sarcomas, germ cell tumors. Therefore, to study the role of R175H in the mammary tumorigenesis, we introduced the R175H allele into the mWnt-1 transgenic mice, which express Wnt-1 transgene in the mammary epithelial cells (MECs) under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) long terminal repeat and develop mammary cancer (14). MWnt-1 mice exhibit expanded mammary stem cell pool and spontaneously develop mammary tumors (15). Here we found that both R175HmWnt-1 and p53−/−mWnt-1 mice had identical survival curves. However, R175HmWnt-1 mice had an increased number of tumors in multiple mammary glands. We also found that R175H could inactivate ATM activity in mWnt-1 MECs and expand MESC pool.

Results

R175HmWnt-1 mice developed multicentric mammary tumors with facilitated kinetics

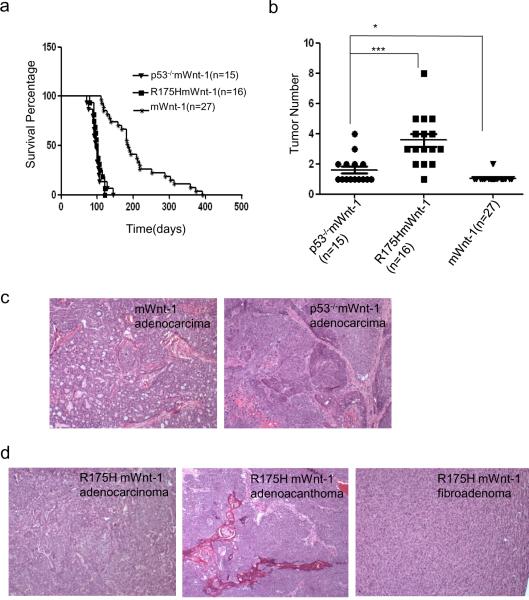

To examine the gain of function of R175H in promoting mammary tumorigenesis, we generated R175HmWnt-1 mice, control p53−/−mWnt-1 and mWnt-1 mice. All three strains of mice developed mammary tumors spontaneously (Figure 1a). However, the median survival time for virgin female R175HmWnt-1 and p53−/−mWnt-1 mice died from breast cancer are 100.5 and 98 days respectively, which are significantly shorter than that of mWnt-1 mice (185 days). The number of mammary tumor developed in p53−/−mWnt-1 (on average 1.5 tumor/mouse) is slightly more than in mWnt-1 female mice that mostly developed only one tumor (Figure 1b). Interestingly, most R175HmWnt-1 female mice developed multiple mammary tumors that affect single or multiple mammary glands (on average 3.5 tumors/mouse) (Figure 1b). Therefore, R175H gains new oncogenic activity to promote the mammary tumorigenesis.

Figure 1.

Mammary tumorigenesis in mWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 mice. (a) Survival curve of mWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice. The survival time of p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice are shorter than mWnt-1 (both of the P value <0.0001), but there is no difference between p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice (P=0.7871). P values were calculated using log-rank test analysis (b) The number of mammary tumors developed in mWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice. The number of tumors in p53−/−Wnt-1 mice is more than in mWnt-1 mice (P=0.0382<0.05); the number of tumors in R175HmWnt1-1 mice is more than in mWnt-1 and p53−/−Wnt-1 mice (P<0.0001 and P=0.0004<0.0005 respectively). P value was obtained from unpaired, 2-tailed t test with Welch's correction. The mean number of mammary tumors in mWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1, and R175HmWnt-1 female mice is 1.056, 1.600 and 3.563 respectively. (c) Mammary tumors developed in mWnt-1 and p53−/−mWnt-1 female mice are all adenocarcinomas and poorly differentiated. (d) Mammary tumors developed in R175HmWnt-1 female mice include adenocarcinomas, fibroadenoma and adenoacanthoma.

In human breast cancer patients, mammary tumors with multiple foci are associated with an advanced stage, regardless of the sizes of the tumors (16). In addition, the breast cancer patients with multicentric mammary tumors exhibit shorter survival time than patients with the unifocal or multifocal mammary cancer (17). The histopathologic analysis of the differentiation grade of human mammary tumors remains one of the most important prognostic factors to predict the prognosis of the cancer patients. To examine whether the expression of R175H affects the differentiation state of mammary cancer, histological examination of the tumor sections showed that all the mammary tumors derived from mWnt-1 and p53−/−mWnt-1 mice are adenocarcinomas (Figure 1c). However, in addition to adenocarcinomas, the fibroadenoma and adenoacanthoma were also found in R175HmWnt-1 mice (Figure 1d). While most mammary tumors from mWnt-1 mice exhibited tubular and typical focal glad formation of tumor cells, most mammary tumors from p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 mice lost the focal glad formation and showed poor differentiation, suggesting that the mammary tumors in p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 mice were of more advanced stage of tumorigenesis (Figure 1c, d).

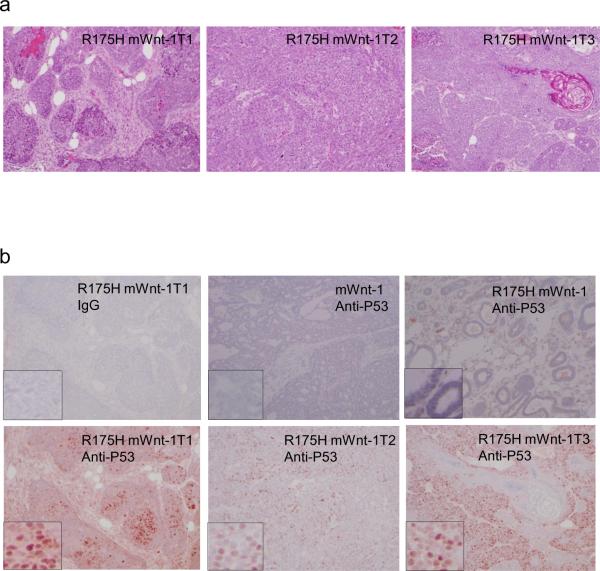

The histological characteristics of the multiple mammary tumors developed in the same R175HmWnt-1 mouse were distinct, more fibroblast tissues was present in tumor 1(T1), while some keratinized areas in the Tumor 3 (T3), suggesting that these mammary tumors might be independent tumors (Figure 2a). Consistent with the findings that p53 cancer mutants are overexpressed in the human breast cancer cells (18), the mammary cancer cells but not their neighboring non-cancerous tissues expressed high levels of R175H, further supporting the notion that R175H promotes the mammary tumorigenesis (Figure 2b). Therefore, our findings of multiple tumors in the mammary glands of R175HmWnt-1 mice and the overexpression of R175H in the cancer cells support the gain of oncogenic function of R175H in promoting the mammary cancer initiation.

Figure 2.

Characterization of mammary tumors developed in the R175HmWnt-1 female mice. (a) H&E stained sections of three mammary tumors developed in the same R175HmWnt-1 mouse. Magnifications are 100×. (b) p53 mutant protein is accumulated in the mammary cancer cells but not in the neighboring normal mammary tissues in R175HmWnt-1 mice.

The MESC pool is significantly expanded in R175HmWnt-1 mice

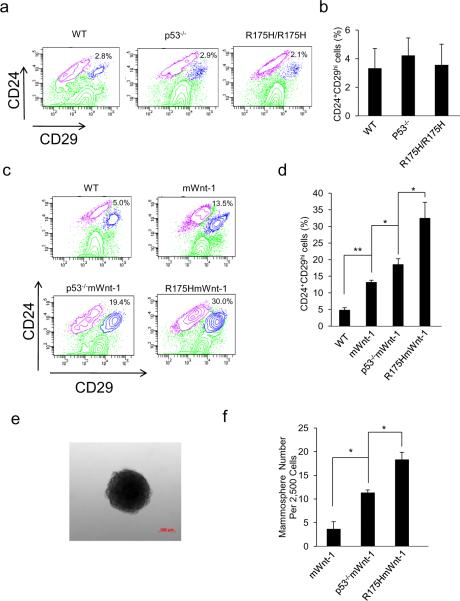

The expression of oncogene Wnt-1 in MECs expands the MESC pool and induces mammary tumorigenesis, suggesting a functional link between the expansive state of the mammary stem cell and breast cancer development (15, 19). Therefore, we analyzed the impact of R175H on the expansion of MESCs. We initially analyzed the MESCs in the wild type (WT), p53−/− and R175H/R175H mammary gland using the MESCs markers Lin−(CD45−CD31−TER119−) CD24+CD29hi as previously described (15). Compared with MESCs in the wild type mice, our results showed that there were no apparent difference of MESCs in the p53−/− and R175H/R175H mice when compared with WT mice (Figure 3a and b). To understand how R175H promotes mammary tumorigenesis in the presence of Wnt-1 transgene, we further analyzed the MESCs in the mammary gland of R175HmWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and mWnt-1 mice. While p53-deficiency led to increased MESCs in mWnt-1 mice, the expression of R175H further increased the MESC population in mWnt-1 mice when compared with p53−/−mWnt-1 mice (Figure 3c and d). In further support of this conclusion, using mammosphere assay widely used to evaluate MESCs with functional characteristics of stem/progenitor cells (20), we showed increased MESCs in R175HmWnt-1 mice when compared with p53−/−mWnt-1 mice (Figure 3e and f). To confirm whether the increased MESCs in R175HmWnt-1 mice are responsible for the mammary tumors, we sorted MESCs (Lin−CD24+CD29hi) and non-stem cells (Lin− but not CD24+CD29hi) from the MECs of R175HmWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and mWnt-1 mice, into the empty fat pad of severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice. Four months after transplantation, 4 of 5 SICD mice transplanted with Lin−CD24+CD29hi cells from R175HmWnt-1 mice and 1 of 5 SICD mice transplanted with Lin−CD24+CD29hi cells from p53−/−mWnt-1 mice developed mammary tumor in both sides of 4th reconstructed empty fat pad of SICD mice. Neither mammary gland nor breast cancer developed in the non-stem cells (Lin– but not CD24+CD29hi) transplanted into the empty fat pad (Supplement Table1 and Figure S1). The histology of the mammary tumors developed in SCID mice transplanted with MESCs sorted from R175HmWnt-1 mice is consistent with the mammary tumor developed in R175Hmwnt-1 mice (Supplementary Figure S2). These results suggest that gain of function of R175H leads to the expansion of the MESC pool in the mWnt-1 mouse model that can be targeted for transformation, thus promoting the initiation of the mammary tumorigenesis. Mammary tumors developed in both sides of the mammary empty fat reconstructed with R175HmWnt-1 mice, but never in the mammary gland of the same SCID mice without the transplantation, supporting the notion that the multiple mammary tumors developed in R175HmWnt-1 mice are not due to the metastasis of a primary tumor.

Figure 3.

R175H promotes the expansion of MESC pool. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of MESCs in wild type, p53−/− and R175H female mice based on the expression of CD24 and CD29. The Lin+ cells were gated out. Percentage of the Lin−CD24+29hi stem cell population is indicated (b). Histogram depicting the percentage (mean±SD) of Lin−CD24+29hi stem cell population in the mammary glands from three independent experiments. (c) Flow cytometric analysis of MESCs in pre-cancerous mWnt-1, p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice based on the expression of CD24 and CD29. The Lin+ cells were gated out. (d) Histogram depicting the percentage (mean±SD) of Lin−CD24+29hi population in female mice of various genotypes from three independent experiments. (e) Micrograph of representative mammosphere. (f) Quantification of mammospheres formed by mWnt-1, P53−/−mWnt-1, R175HmWnt-1 MECs. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. “*” Indicated P<0.05. P value was obtained from unpaired, 2-tailed t test with Welch's correction.

Impaired ATM function in R175HmWnt-1 mammary epithelial cells

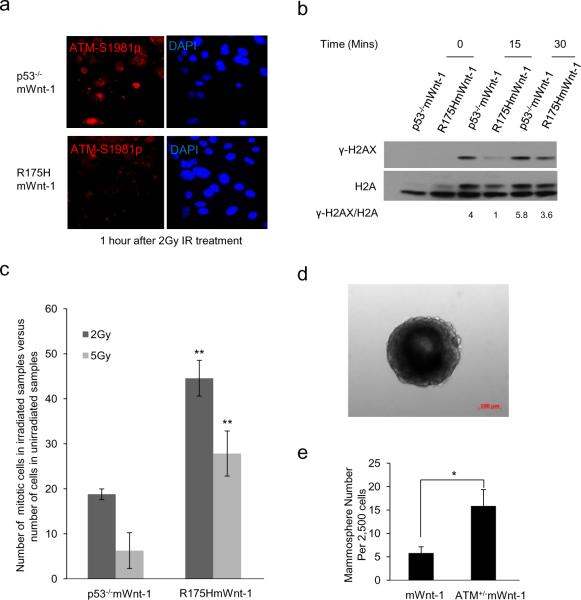

ATM is important to suppress mammary tumorigenesis and the expansion of normal and transformed mammary stem cells (21–24). Since our previous studies have shown that the common p53 cancer mutants including R175H inactivate Mre11/ATM in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and thymocytes (12), we tested whether R175H has the same gain of function in mammary epithelial cells. Immediately after DNA double-stranded break damage, activated ATM, which is autophosphorylated at Ser1981 (Bakkenist and Kastan, 2003), was recruited to the site of DNA damage and form IR induced foci (IRIF). When compared with that in p53−/−mWnt-1 mammary epithelial cells, the IRIF of phosphorylated ATM was significantly impaired in R175HmWnt1 mammary epithelial cells, indicating that ATM activation is impaired in R175HmWnt1 MECs after IR (Figure 4a). Furthermore, compared with that in p53−/− mWnt-1 MECs, the ATM-dependent phosphorylation of H2AX (γ-H2AX) after IR was impaired in R175HmWnt-1 MECs (Figure 4, b). In addition, we analyzed the ATM-dependent G2/M checkpoint after IR, demonstrating that the G2/M checkpoint was significantly impaired in R175HmWnt1 MECs compared with that in p53−/−mWnt-1 MECs (Figure 4c). These results support the notion that R175H inactivates ATM in Wnt-1-expressing MECs.

Figure 4.

Impaired ATM activation and function in MECs of R175HmWnt-1 female mice. (a) IRIF of ATM-1981p in the MECs from p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice 1 hr after IR (2Gy). (b) ATM-dependent phosphorylation of H2AX (γ-H2AX) 15 and 30 min after IR (2Gy) is impaired in MECs of R175HmWnt-1 mice when compared with those of p53−/−mWnt-1 mice. The densitometric ratio γ-H2AX/H2AX is shown below. (c) G2/M checkpoint in the MECs of p53−/−mWnt-1 and R175HmWnt-1 female mice after increasing dosages of IR. (d) Micrograph of representative mammosphere formed by R175HmWnt-1 MECs. (e) Quantification of mammospheres formed by mWnt-1 and ATM+/−mWnt-1 MECs. Mean value from independent experiments are shown with SD (n=3), “*” indicate P<0.05; “**” showed P<0.01, P value was obtained from unpaired, 2-tailed t test with Welch's correction.

Consistent with the findings that ATM suppresses the expansion of MESCs, more mammosphere formation was observed in the MECs from ATM+/−mWnt-1 mice than those from mWnt-1 mice (Figure 4, d and e). In addition, ATM+/−p53+/− mice developed breast cancer with an increased average number of mammary carcinomas per mouse, indicating a role of ATM in suppressing the development of multicentric mammary tumors. Therefore, our findings support the model that R175H gains new oncogenic activities in inactivating ATM in MECs, contributing to the expansion of mammary stem cell pool and the multicentric mammary tumorigenesis. The distinct impact of R175H on MESCs in R175H and R175HmWnt-1 mice might be due to the elevated DNA damage in the mammary gland with Wnt-1 expression, because the increased DNA damage in the mammary gland as a result of Wnt-1 expression activates ATM (25).

Discussion

While the p53 gene is frequently mutated in human bresat cancer and the expression of p53 cancer mutants correlated with the poor prognosis of the breast cancer patients, the gain of oncogenic functions of p53 cancer mutants in breast cancers remain unclear. Using the common gain of function of p53 cancer mutant knock-in mice, we have identified a novel role of this common p53 cancer mutant in promoting the expansion of the MESCs that are correlated with mammary tumorigenesis(15, 19, 26). Based on the findings that inactivation of ATM could expand normal and transformed MESCs(21–24), our findings that R175H mutant inhibits ATM activity in mammary epithelial cells could account for the increased MESCs by inhibiting ATM activity. Since ATM inactivation appears to be a common gain of function among the most frequent p53 cancer mutants(12, 13), our findings suggest that the common p53 cancer mutants could share this gain of oncogenic activity in promoting mammary tumorigenesis by inactivating ATM. While our data point to a gain of function of R175H mutant in promoting breast cancer by inactivating ATM, we cannot rule out the possibility that one or more additional gain of function of R175H mutant also contributes to the breast cancer phenotype. In this context, other gain of functions of R175H cancer mutant include the regulation of the functions of p63 and p73 (27), the TGF-beta/Smad pathway (28), Daxx (29), MBP1 (30), Integrin (31), NF-Y (32), Nuclear factor κB (33), promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein (34). The contribution of these gain of functions of R175H to the increased MESCs and multiple breast cancers in R175HmWnt-1 mice remains to be investigated.

Many current breast cancer therapies such as radiation therapy or treatment with topoisomerase inhibitors eliminate the cancer cells by inducing high levels of DNA DSB damage into their genome. ATM is responsible for activating cellular responses to DNA DSB damage and maintaining genomic stability (35). Therefore, when treating p53 cancer mutant expressing breast cancers with these DNA damage agents, the combination of impaired ATM function and the lack of effective cell death pathways might induce genetic instability and thus promote drug resistance of the breast cancer cells that survive the treatments. Our findings in this mouse model suggest that the overexpression of R175H promotes the early stage of mammary tumorigenesis partially by inactivating ATM. Therefore, destabilization of this common p53 cancer mutant and restoration of ATM function could improve the efficiency of current therapies in eliminating breast cancer cells expressing R175H.

Methods

Isolation and culture of primary mammary epithelial cell from mouse

MECs were isolated as before (15). Breast glands were dissected from 8-week-old female mice, and minced with a razor blade. The tissue was placed in culture medium (DMEM/F12 with 1mM glutamine, 5 μg/ml insulin, 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor and 20 ng/ml cholera toxin) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone) and containing 300U/ml collagenase IV (Invitrogen) and 100U/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma), and digested for 1 hr at 37 °C. The resultant organoid suspension was sequentially digested in 0.25% trypsin-EGTA for 2min, 5mg/ml dispase (Stemcell technologies) and 0.1mg/ml DNase (Stemcell technologies) for 5min, and 0.64% NH4Cl for 3min before filtration through a 40-μmcell strainer. The filtrated cell ware cultured or labeled. The cell culture medium was used as before(36),Cells were cultured in complete growth media containing 5 μg/ml insulin, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 3 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF),10%FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen). All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Histology analysis

Mammary gland and mammary cancer samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sliced. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological assessment as previously described (12), the PAb1081 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used for immunochemistry.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were stained at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per 100μl of FACS buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline with 2% FBS and 0.09% sodium azide). Cells were first labeled with biotin-conjugated anti-mouse TeR-119, CD45, CD31 (eBioscicence) at appropriate dilutions at 4C for 15 min, after washed with FACS buffer for three times, stained with APC-strepavidin (ebioscience), PE-anti-CD24 (Biolegend), FITC-anti-CD29 (Biolegend) at appropriate dilutions at 4C for 15 mins. The stained samples were then analyzed using BD LSR II™ flow cytometer. Cell sorting was carried out on BD FACSAria™ II cell sorter.

Mammosphere culture

Mammosphere culture was performed as described (20). The isolated MECs were cultured in MEC culture medium for 1 day. Single cells were plated in ultralow attachment plates (Corning) at a density of 25,000 viable cells/ml in primary culture. Cells were grown in a serum-free mammary epithelial growth medium (Lonza), supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen), 20 ng/mL EGF (Sigma) and 20 ng/mL bFGF (Invitrogen), and 4μg/mL heparin (Sigma). Half of the medium was changed every 3 days. The mammospheres were cultured for 20 days, and the ones with diameter >50 μm were counted.

Cell cycle analysis

To analyze the G2-M checkpoint, asynchronously growing MECs were irradiated (2 and 5 Gy) and harvested 1 hr after treatment. Cells in mitosis were identified by staining with propidium iodide for DNA content and FITC-conjugated antibody recognizing Histone 3 phosphorylated at Ser 10 (Millipore).

Western blotting analysis

Protein extract from 4×105 MECs was resolved on 12–15% SDS polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, which was probed with anti-γ-H2AX and anti-H2A antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). The membrane was subsequently probed with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody and developed with Super signal West Dura (Thermo).

Immunoflorescence microscopy

Primary MECs grown on Lab-TekTM Chamber Slide (Thermo) were exposed to 2 Gy of IR, and 1hr later, fixed with methanol. The fixed cells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30min at room temperature, and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing ATM phosphorylated at Ser1981 (1:600 dilution; Rockland Inc.) in 1% BSA in PBS for overnight at 4C. After washing, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. After mounting on glass slides with VECTASHIELD mounting media with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories), images were acquired by Olympus confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Yi Li for the MMTV-Wnt-1 mice. This work was supported by Grants from the NIH (R01 CA94254) and DOD Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-08-1-0381) to YX.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elledge RM, Allred DC. The p53 tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:39–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00666204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin SC, Lee KF, Nikitin AY, Hilsenbeck SG, Cardiff RD, Li A, et al. Somatic mutation of p53 leads to estrogen receptor alpha-positive and -negative mouse mammary tumors with high frequency of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3525–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donehower LA, Godley LA, Aldaz CM, Pyle R, Shi YP, Pinkel D, et al. Deficiency of p53 accelerates mammary tumorigenesis in Wnt-1 transgenic mice and promotes chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:882–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meek DW. Tumour suppression by p53: a role for the DNA damage response? Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:714–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasco M, Shami S, Crook T. The p53 pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:70–6. doi: 10.1186/bcr426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain SP, Harris CC. Molecular epidemiology and carcinogenesis: endogenous and exogenous carcinogens. Mutat Res. 2000;462:311–22. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittmer D, Pati S, Zambetti G, Chu S, Teresky AK, Moore M, et al. Gain of function mutations in p53. Nat Genet. 1993;4:42–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li B, Murphy KL, Laucirica R, Kittrell F, Medina D, Rosen JM. A transgenic mouse model for mammary carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 1998;16:997–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang XJ, Greenhalgh DA, Jiang A, He D, Zhong L, Brinkley BR, et al. Analysis of centrosome abnormalities and angiogenesis in epidermal-targeted p53172H mutant and p53-knockout mice after chemical carcinogenesis: evidence for a gain of function. Mol Carcinog. 1998;23:185–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199811)23:3<185::aid-mc7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu DP, Song H, Xu Y. A common gain of function of p53 cancer mutants in inducing genetic instability. Oncogene. 2010;29:949–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song H, Hollstein M, Xu Y. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:573–80. doi: 10.1038/ncb1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukamoto AS, Grosschedl R, Guzman RC, Parslow T, Varmus HE. Expression of the int-1 gene in transgenic mice is associated with mammary gland hyperplasia and adenocarcinomas in male and female mice. Cell. 1988;55:619–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML, et al. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature. 2006;439:84–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabioglu N, Ozmen V, Kaya H, Tuzlali S, Igci A, Muslumanoglu M, et al. Increased lymph node positivity in multifocal and multicentric breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissenbacher TM, Zschage M, Janni W, Jeschke U, Dimpfl T, Mayr D, et al. Multicentric and multifocal versus unifocal breast cancer: is the tumor-node-metastasis classification justified? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidoff AM, Humphrey PA, Iglehart JD, Marks JR. Genetic basis for p53 overexpression in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5006–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCoy EL, Iwanaga R, Jedlicka P, Abbey NS, Chodosh LA, Heichman KA, et al. Six1 expands the mouse mammary epithelial stem/progenitor cell pool and induces mammary tumors that undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2663–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI37691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy JP, Peddibhotla S, Bu W, Zhao J, Haricharan S, Du YC, et al. Defining the ATM-mediated barrier to tumorigenesis in somatic mammary cells following ErbB2 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910665107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Yu Y, Tsuyada A, Ren X, Wu X, Stubblefield K, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates the sphere-initiating stem cell-like feature in breast cancer through miRNA-181 and ATM. Oncogene. 2011;30:1470–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu S, Shen K, Wang Y, Santner SJ, Chen J, Brooks SC, et al. Atm-haploinsufficiency enhances susceptibility to carcinogen-induced mammary tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:848–55. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowen TJ, Yakushiji H, Montagna C, Jain S, Ried T, Wynshaw-Boris A. Atm heterozygosity cooperates with loss of Brca1 to increase the severity of mammary gland cancer and reduce ductal branching. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8736–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayyanan A, Civenni G, Ciarloni L, Morel C, Mueller N, Lefort K, et al. Increased Wnt signaling triggers oncogenic conversion of human breast epithelial cells by a Notch-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F, Sheridan JM, Pal B, Wu D, Simpson ER, et al. Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature. 2010;465:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature09027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalo E, Buganim Y, Shapira KE, Besserglick H, Goldfinger N, Weisz L, et al. Mutant p53 attenuates the SMAD-dependent transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-beta1) signaling pathway by repressing the expression of TGF-beta receptor type II. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8228–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00374-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitamura T, Fukuyo Y, Inoue M, Horikoshi NT, Shindoh M, Rogers BE, et al. Mutant p53 disrupts the stress MAPK activation circuit induced by ASK1-dependent stabilization of Daxx. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7681–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallagher WM, Argentini M, Sierra V, Bracco L, Debussche L, Conseiller E. MBP1: a novel mutant p53-specific protein partner with oncogenic properties. Oncogene. 1999;18:3608–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller PA, Caswell PT, Doyle B, Iwanicki MP, Tan EH, Karim S, et al. Mutant p53 drives invasion by promoting integrin recycling. Cell. 2009;139:1327–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Agostino S, Strano S, Emiliozzi V, Zerbini V, Mottolese M, Sacchi A, et al. Gain of function of mutant p53: the mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisz L, Damalas A, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Fontemaggi G, Maor-Aloni R, et al. Mutant p53 enhances nuclear factor kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2396–401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haupt S, di Agostino S, Mizrahi I, Alsheich-Bartok O, Voorhoeve M, Damalas A, et al. Promyelocytic leukemia protein is required for gain of function by mutant p53. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4818–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y. DNA damage: a trigger of innate immunity but a requirement for adaptive immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:261–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smalley MJ. Isolation, culture and analysis of mouse mammary epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;633:139–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-019-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.