Abstract

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells are associated with tumor prognosis, although the type of immune cells responsible for local immune escape is still unknown. This study examined the relationship between gastric cancer survival and the density of immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells, which represent myeloid-derived suppressor cells, to evaluate the role of immune cells in the progression of gastric cancer. One hundred pathologically confirmed specimens were obtained from stage IIIa gastric cancers between 2003 and 2006 at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, China. The density of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in tumor tissue was examined using immunohistochemical analysis. Clinicopathologic parameters and the survival rate were analyzed in relation to the density of immune cells. A high density of CD8+ T cells and CD20+ B cells was associated with a good clinical outcome, but a high density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells was associated with a poor clinical outcome. Most importantly, the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells was an independent prognostic factor and inversely related to the infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Although the infiltration of CD8+ T cells and CD20+ B cells is involved in the progression of gastric cancer, these data suggest that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells play a central role in the regulation of the local immune response, suggesting that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells might be therapeutic targets in gastric cancer.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, CD33, STAT1, T cell, B cell, Regulation

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most aggressive diseases worldwide, particularly in Asian countries, such as China [1]. In addition, gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death each year due to the resistance and intolerance of this cancer to cytotoxic therapy [2–4]. New therapeutic strategies are needed to treat gastric cancer. Recently, immunotherapy has received increased attention because antibodies targeting immune checkpoint molecules and therapeutic vaccines have been identified [5–8]; therefore, identifying patients who are suitable for immune therapy is critical.

The density of tumor-infiltrating immune cells is associated with the prognosis of multiple types of tumors [9–13]. However, tumor-infiltrating immune cells consist of both tumor-rejecting cells and tumor-promoting cells. Therefore, a detailed analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells would lead to more effective prognostic indicators, and their potential use as biomarkers for immunotherapy could be determined [14, 15].

Immune cells infiltrates are different among tumor types and from patient to patient. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are considered to be a manifestation of the host immune reaction to cancer cells [16]. Large numbers of T and B lymphocytes are associated with a good clinical outcome in many different tumor types [13, 17–26].

In addition to tumor-rejecting immune cells, immune suppressor cells play a pivotal role in tumor progression. Recently, several studies have demonstrated the importance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in tumor-associated immune suppression [27, 28]. MDSCs are recognized as a heterogeneous population of myeloid cells that consist of immature myeloid cells (IMCs) and myeloid cells at early stages of differentiation [27, 29, 30]. The role of the MDSCs that infiltrate into solid tumor tissue is still unclear. An obstacle to assaying the role of MDSCs in human tissue is the lack of defined markers for MDSCs. Among the markers reported, CD33 and CD11b are the basic markers of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Although they are feasible to assay in blood cells, staining cells in tissue for multiple markers is very difficult, especially for markers with the same subcellular localization. To develop a set of markers that are suitable for the detection of infiltrative MDSCs, we reviewed the mechanisms of activation and expansion of MDSCs. The expansion and activation of MDSCs are influenced by several different factors, including VEGF, GM-CSG, SCF, TGF-β, and MMP9, among others [31–39]. These factors trigger the activation of several different signaling pathways in MDSCs that promote JAK-STAT signaling, including STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 [28, 40]. To investigate this role, CD33 was used as a marker of immature myeloid cells, and p-STAT1 was used as a marker of IMCs activated by immune regulatory cytokines [40, 41]. Therefore, CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells were proposed to be a subset of MDSCs in gastric cancer tissues. This study examined the relationship between the survival rate of gastric cancer and the density of immune cells, including TILs and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells, which represented MDSCs, to evaluate the role of the immune response in gastric cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Tissue specimens

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues from 100 gastric cancer patients were used. Gastric cancer biopsy specimens were collected from stage IIIa (2009 UICC staging system) gastric cancer patients between 2003 and 2006 at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. All of the patients underwent radical resection, and none of the patients had chemotherapy or radiotherapy before sample collection. Patients received 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy post-operatively for 6 months. If recurrence or metastasis occurred, 5-FU-based chemotherapy was given according to the NCCN guidelines. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients signed a consent form approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Immunohistochemistry and scoring systems

Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned continuously at a thickness of 4 μm and heated for 1 h at 65 °C. Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized using xylenes and rehydrated with a graded alcohol series and distilled water. The sections were immersed in an EDTA antigen retrieval buffer (pH 8.0), subjected to high pressure for 3 min for antigen retrieval and allowed to cool to room temperature. After blocking with sheep serum, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal antibodies against human CD8, CD20, and GrB (Zymed, San Diego, CA, USA), all of which were diluted 1:400. Following incubation with secondary antibodies, the sections were developed using diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

The co-expression of CD33 and p-STAT1 was detected with sequential immunohistochemical staining using the EnVison™ G/2 Doublestain System (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Endogenous peroxidases and alkaline phosphatase enzymes were blocked with the dual endogenous enzyme-blocking reagent provided in the kit. The sections were treated with normal goat serum for 20 min to reduce nonspecific binding and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal anti-CD33 antibody (1:100; Protein Tech Group, Chicago, IL, USA) and rabbit monoclonal anti-p-STAT1 (1:400; Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA). For the color reaction, diaminobenzidine (brown) and permanent red (red) were must used. As a negative control, the antibodies were replaced with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

The density of immune cells within the tumor specimens was scored as we previously reported [14]. Briefly, the number of cells and the cell size were counted in at least 10 different fields of each section. The size of each high-powered field (400×) was approximately 300 μm × 300 μm, and the cells were counted in the intratumoral compartment. The areas of highest density were chosen, and necrotic areas were avoided. Two observers counted the cells at the same time in the same field using a multiple-lens microscope. The median value was used to distinguish the different groups of immunohistochemical variables in the results.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 16.0 statistical software package. The median value was used to differentiate high- and low-density groups for each immunohistochemical variable. The correlation between the density of immune cells and patient characteristics and the correlation between the density of TILs and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells were analyzed using correlation test. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate the distribution of variables in relation to survival, which were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were based on the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Overall survival (OS) was defined as death from any cause, and disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time prior to relapse of the primary tumor. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 100 patients, there were 71 men and 29 women, and the median age was 59.5 years, with a range of 29–82 years. Fifty-five patients (55 %) were Borrmann classification II, 38 were Borrmann classification III, and 7 cases were Borrmann classification I or IV. All of the patients presented lymph node metastasis before treatment, with 36 patients at the N1 stage, 34 patients at the N2 stage, and 30 patients at the N3 stage. During follow-up, 54 died, and 44 presented with disease progression.

CD8, CD20, GrB, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells in gastric cancer tissues

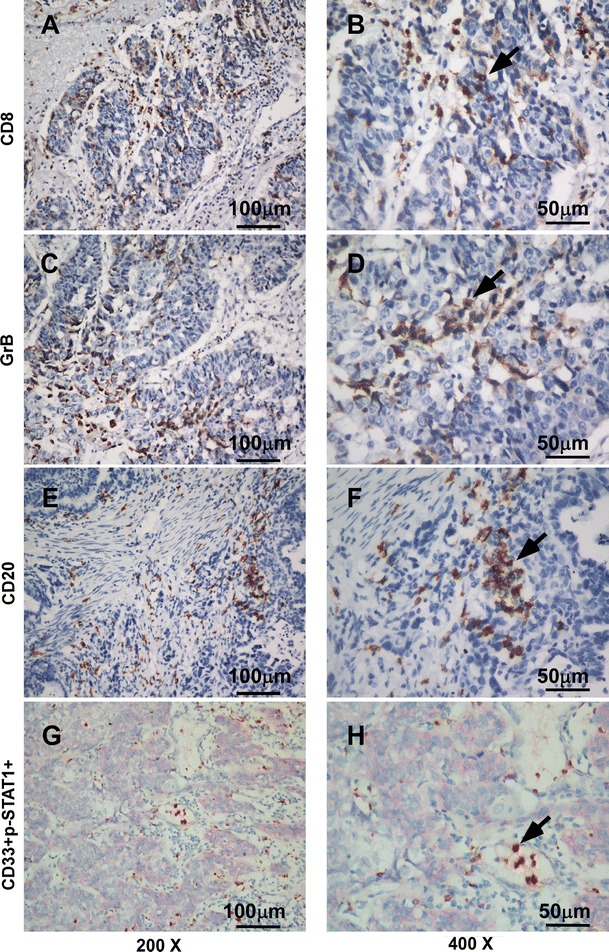

CD8+, CD20+, and GrB+ lymphoid cells displayed strong membrane staining (Fig. 1a–f). CD8+ T cells and CD20+ B cells were primarily observed in cancer nests and along the invasive margin. The infiltrating lymphoid cells in the intratumoral compartment were counted.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for CD8, CD20, GrB, and double immunohistochemical staining for CD33 and p-STAT1 (200× and 400×). a, b CD8+ T lymphocytes in gastric cancer tissue. c, d GrB+ active cytotoxic T lymphocytes in gastric cancer tissue. e, f CD20+ B lymphocytes in gastric cancer tissue. g, h Gastric cancer tissue stained for CD33+ (red) and p-STAT1+ (brown)

To characterize MDSC infiltration in gastric cancer tissue, we defined MDSCs as CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells. These CD33+/p-STAT1+ double-positive cells have been found mostly in the stroma among gastric cancer (Fig. 1g, h), whereas they had not yet been observed in the normal mucosa adjacent to gastric cancer and normal mucosa far from the gastric cancer (data not shown). The CD33 immunostaining demonstrated cytomembrane staining, and p-STAT1 demonstrated nucleus staining. Figure 1g, h shows the CD33/p-STAT1 double-positive cells in a subset of cells around the tumor nests.

Relationship between the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells and the density of CD8+ and CD20+ lymphocytes

The correlation test was used to compare the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells with the density of CD8+ and CD20+ lymphocytes (Table 1). A higher density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells within tumor nests was associated with a lower density of CD8+ T cells (Spearman’s rho = −0.538, p < 0.001). However, CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells were not significantly associated with the density of CD20+ B lymphocytes (Spearman’s rho = −0.036, p = 0.721).

Table 1.

Relationship between CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells and the density of TILs

| CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | p value | |

| Density of CD8+ T cells | −0.538 | <0.001 |

| Density of CD20+ B cells | −0.036 | 0.721 |

Relationship between the density of CD8, CD20, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells and clinicopathologic characteristics

The immune cells were divided into two groups based on the median value (high density and low density). The cutoff value for the density of CD8, CD20, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ groups was 28, 34, and 11 cells, respectively, per high-powered field in the center of the tumor. The density of immune cells was analyzed to identify any association with the clinicopathologic features of gastric cancer. As shown in Table 2, the density of CD8+ T cells and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells was significantly correlated with patient vital status (p = 0.023, p < 0.001) and relapse occurrence (p = 0.005, p = 0.001); in addition, the high-density group of CD8+ T cells had a smaller tumor size (p = 0.005). However, the density of the immune cells was not significantly associated with gender, age, or Borrmann classification.

Table 2.

Correlation between clinicopathologic features and immune cell density

| Characteristics | CD8+ T lymphocytes | CD20+ B lymphocytes | CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High density | Low density | p | High density | Low density | p | High density | Low density | p | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 62) | (n = 43) | (n = 57) | (n = 43) | (n = 57) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 31 | 40 | 0.068 | 32 | 39 | 0.513 | 28 | 43 | 0.260 |

| Female | 7 | 22 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 14 | |||

| Age (year) | |||||||||

| <60 | 11 | 17 | 0.869 | 10 | 18 | 0.359 | 14 | 14 | 0.378 |

| ≥60 | 27 | 45 | 33 | 39 | 29 | 43 | |||

| Borrmann classification | |||||||||

| I | 2 | 2 | 0.554 | 2 | 2 | 0.884 | 1 | 3 | 0.950 |

| II | 23 | 32 | 22 | 33 | 24 | 31 | |||

| III | 13 | 25 | 18 | 20 | 17 | 21 | |||

| IV | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Tumor size (cm3) | |||||||||

| <20 | 25 | 23 | 0.005 | 20 | 28 | 0.796 | 22 | 26 | 0.582 |

| ≥20 | 13 | 39 | 23 | 29 | 21 | 31 | |||

| Vital status | |||||||||

| Alive | 23 | 23 | 0.023 | 19 | 27 | 0.752 | 9 | 37 | <0.001 |

| Dead | 15 | 39 | 24 | 30 | 34 | 20 | |||

| Relapse | |||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 34 | 0.005 | 18 | 26 | 0.708 | 27 | 17 | 0.001 |

| No | 28 | 28 | 25 | 31 | 16 | 40 | |||

Association of the density of immune cells with patient survival

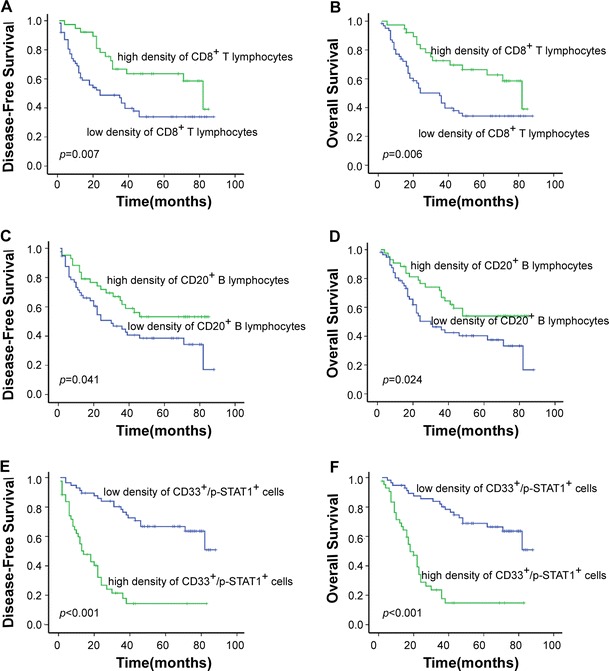

The median follow-up time was 36.5 months, with a range of 2–88 months. The median DFS was 32.5 months, with a range of 2–88 months. At the completion of the study, 46 patients with stage IIIa gastric cancer were alive, whereas 54 patients had died. Fifty-two deaths were cancer related, and two deaths were unrelated to cancer. The cumulative 5-year survival rate was 32.0 % for all patients with stage IIIa gastric cancer. We evaluated whether the density of immune cells was associated with patient prognosis. The disease-free survival time differed significantly between the immune cell groups (CD8+ T cells: p = 0.007; CD20+ B cells: p = 0.041; CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells: p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Patients with a high density of lymphocytes had a longer DFS time than those with low density. We next analyzed the association between the density of immune cells and OS time (CD8+ T cells: p = 0.006; CD20+ B cells: p = 0.024; CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells: p < 0.001; Fig. 2). The cumulative 5-year survival rate was 50.9 % in the low-density CD33+/p-STAT1+ group but only 7.0 % in the high-density CD33+/p-STAT1+ group.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease-free survival and overall survival for each immune cell group. A high density of CD8+ T lymphocytes and CD20+ B lymphocytes was associated with a longer overall survival and longer disease-free survival than a low density, but the inverse result was observed for CD33+/p-STAT1+ cell density

Univariate analysis demonstrated that age, and the density of CD8, CD20, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells were significant prognostic factors for OS and DFS (Table 3). However, clinical prognosis was not associated with gender, age, Borrmann classification, size of the tumor, or N stage.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with OS and DFS

| Variables | OS (n = 100) | DFS (n = 100) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95 % CI) | p value | HR (95 % CI) | p value | |

| Gender | 1.636 (0.934–2.864) | 0.085 | 1.587 (0.906–2.778) | 0.106 |

| Age | 1.903 (1.094–3.311) | 0.023 | 1.946 (1.118–3.390) | 0.019 |

| Borrmann classification | 1.124 (0.750–1.685) | 0.570 | 1.129 (0.751–1.696) | 0.561 |

| Size of tumor | 1.255 (0.733–2.148) | 0.408 | 1.278 (0.746–2.187) | 0.372 |

| N stage | 0.828 (0.586–1.169) | 0.283 | 0.835 (0.594–1.175) | 0.301 |

| CD8+ T cells | 0.446 (0.245–0.811) | 0.008 | 0.452 (0.249–0.821) | 0.009 |

| CD20+ B cells | 0.533 (0.304–0.934) | 0.028 | 0.566 (0.323–0.991) | 0.046 |

| CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells | 5.318 (2.965–9.538) | <0.001 | 5.330 (2.971–9.561) | <0.001 |

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis

A multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed for age, and the density of CD8, CD20, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells. Of the 100 stage IIIa gastric cancer patients, the Cox regression model revealed that only patients with a higher density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells had a significantly reduced OS (hazard ratio [HR]: 4.674; 95 % CI: 2.525–8.625) and DFS (HR: 4.670; 95 % CI: 2.537–8.596) compared to the low CD33+/p-STAT1+ group. However, CD8 and CD20 were not associated with OS or DFS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with OS and DFS

| Variables | OS (n = 100) | DFS (n = 100) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95 % CI) | p value | HR (95 % CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.515 (0.857, 2.677) | 0.153 | 1.603 (0.903, 2.846) | 0.107 |

| CD8+ T cells | 0.595 (0.321, 1.101) | 0.098 | 0.571 (0.309, 1.054) | 0.073 |

| CD20+ B cells | 0.555 (0.312, 0.986) | 0.045 | 0.632 (0.356, 1.121) | 0.116 |

| CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells | 4.674 (2.525, 8.652) | <0.001 | 4.670 (2.537, 8.596) | <0.001 |

Discussion

To enhance our understanding of the contribution of the local immune response to the progression of gastric cancer, this study characterized CD8+ T lymphocytes, CD20+ B lymphocytes, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells in the intratumoral region. The results showed that the density of CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells in tumors was a useful criterion for the prediction of survival in advanced gastric cancer patients. Most importantly, Cox multivariate analysis demonstrated that the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells within the cancer tissue was an independent prognostic factor. These data indicated that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells play an important role in the progression of gastric cancer.

Several recent studies have analyzed the important role of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8+ T and B lymphocytes in the antitumor immune response [42–49]. The effects of CD8+ T cells in cancer cell nests might be related to the effector function of killer T cells, and the role of B lymphocytes as part of the adaptive humoral immune response has been associated with improved survival in several types of cancer [25, 26, 50].

Although some studies have indicated that immune surveillance and immune escape exist in gastric cancer [51–53], the type of immune cells responsible for local immune escape is still unknown. Experimental data indicated that MDSCs suppress the immune response, in contrast to CD8+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. The main obstacle is the markers for MDSCs in the human tissue. As mentioned above, besides the basic markers of human MDSCs, the signaling pathways associate with the MDSCs expansion and activation are also very important. STAT1 is one of the pathways in MDSCs activation; Gabrilovich demonstrated that STAT1 activation in tumor-associated macrophages is responsible for the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and arginase 1 activity in these cells, which results in T-cell suppression [41]. STAT1-deficient MDSCs are unable to inhibit T-cell activation due to their inability to upregulate iNOS and arginase 1 activity [54, 55]. Therefore, CD33 staining on the cell membrane was used as a marker of myeloid cells in this study, and p-STAT1 nuclear staining was used to represent a transcription factor activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines. For this reason, CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells are defined as a specific type of MDSC in gastric cancer tissues, although further functional analysis is required. Using this set of MDSC markers, it was possible to examine the infiltration of MDSCs into cancer tissues.

To confirm the role of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells, which represented MDSCs in gastric cancer tissue, this study detected the density of CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and CD33+/p-STAT1+ immune cells infiltrating tumor tissue. A higher density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells was inversely related to infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes but not B cells, supporting that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cell might be a subset of MDSCs in gastric tumor tissue. Although Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank tests revealed that the all of the immune cells were significantly associated with OS and DFS duration, Cox multivariate analysis demonstrated that only the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells within the cancer tissue was a prognostic factor for OS and DFS, independently, indicating that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells play a key role in the regulation of the local immune response.

Overall, this study demonstrated that the density of CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells is an independent prognostic factor for patients with stage IIIa gastric cancer, indicating that CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells play a central role in the local immune response in gastric cancer. Therefore, CD33+/p-STAT1+ cells might be a useful therapeutic target.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (30972882, 81272341) and the Key Project of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2008B030301079).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Contributor Information

Ying-Bo Chen, Email: chenyb@sysucc.org.cn.

Xiao-Shi Zhang, Phone: +86-20-87343382, FAX: +86-20-87343382, Email: zhangxsh@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roder DM. The epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-002-0203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang L. Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(1):17–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23(38):6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, M D JW, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilic A, Landreneau RJ, Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Schuchert MJ. Density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with disease recurrence and survival in patients with large non-small-cell lung cancer tumors. J Surg Res. 2011;167(2):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. The role of the in situ local inflammatory response in predicting recurrence and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):451–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, Daemen T, Nijman HW. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):93–103. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng RQ, Wu XJ, Ding Y, Li CY, Yu XJ, Zhang X, et al. Co-expression of nuclear and cytoplasmic HMGB1 is inversely associated with infiltration of CD45RO+ T cells and prognosis in patients with stage IIIB colon cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:496. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Peng RQ, Wu XJ, Xia Q, Hou JH, Ding Y, et al. The density of macrophages in the invasive front is inversely correlated to liver metastasis in colon cancer. J Transl Med. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg SA. The immunotherapy of solid cancers based on cloning the genes encoding tumor-rejection antigens. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:481–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menegaz RA, Michelin MA, Etchebehere RM, Fernandes PC, Murta EF. Peri- and intratumoral T and B lymphocytic infiltration in breast cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29(4):321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):610–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano O, Sato M, Naito Y, Suzuki K, Orikasa S, Aizawa M, et al. Proliferative activity of intratumoral CD8(+) T-lymphocytes as a prognostic factor in human renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic demonstration of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5132–5136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawai O, Ishii G, Kubota K, Murata Y, Naito Y, Mizuno T, et al. Predominant infiltration of macrophages and CD8(+) T Cells in cancer nests is a significant predictor of survival in stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Charoentong P, Kirilovsky A, Bindea G, Berger A, et al. Biomolecular network reconstruction identifies T-cell homing factors associated with survival in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(4):1429–1440. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halama N, Michel S, Kloor M, Zoernig I, Benner A, Spille A, et al. Localization and density of immune cells in the invasive margin of human colorectal cancer liver metastases are prognostic for response to chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(17):5670–5677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gobert M, Treilleux I, Bendriss-Vermare N, Bachelot T, Goddard-Leon S, Arfi V, et al. Regulatory T cells recruited through CCL22/CCR4 are selectively activated in lymphoid infiltrates surrounding primary breast tumors and lead to an adverse clinical outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2000–2009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang YL, Li J, Mo HY, Qiu F, Zheng LM, Qian CN, et al. Different subsets of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with NPC progression in different ways. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milne K, Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Barnes RO, Gao D, Gilks CB, et al. Systematic analysis of immune infiltrates in high-grade serous ovarian cancer reveals CD20, FoxP3 and TIA-1 as positive prognostic factors. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoud SM, Lee AH, Paish EC, Macmillan RD, Ellis IO, Green AR. The prognostic significance of B lymphocytes in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(2):545–553. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55(3):237–245. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talmadge JE. Pathways mediating the expansion and immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their relevance to cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1):5243–5248. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181(8):5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G, Bronte V, Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabrilovich D, Ishida T, Oyama T, Ran S, Kravtsov V, Nadaf S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Blood. 1998;92(11):4150–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bronte V, Chappell DB, Apolloni E, Cabrelle A, Wang M, Hwu P, et al. Unopposed production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by tumors inhibits CD8+ T cell responses by dysregulating antigen-presenting cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;162(10):5728–5737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filipazzi P, Valenti R, Huber V, Pilla L, Canese P, Iero M, et al. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan PY, Wang GX, Yin B, Ozao J, Ku T, Divino CM, et al. Reversion of immune tolerance in advanced malignancy: modulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cell development by blockade of stem-cell factor function. Blood. 2008;111(1):219–228. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-086835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta: tumor suppressor or promoter? Are host immune cells the answer? Cancer Res. 2008;68(22):9107–9111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melani C, Sangaletti S, Barazzetta FM, Werb Z, Colombo MP. Amino-bisphosphonate-mediated MMP-9 inhibition breaks the tumor-bone marrow axis responsible for myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and macrophage infiltration in tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2007;67(23):11438–11446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+ CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, Huang J, Ren X, Gorska AE, Chytil A, Aakre M, et al. Abrogation of TGF beta signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+ CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. STAT1 signaling regulates tumor-associated macrophage-mediated T cell deletion. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4880–4891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, Ohuchi A, Saigenji K, Nagura H, et al. CD8+ T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3491–3494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guidoboni M, Gafa R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Santini A, et al. Microsatellite instability and high content of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes identify colon cancer patients with a favorable prognosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(1):297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberg A, Samii S, Stenling R, Lindmark G. Different occurrence of CD8+, CD45R0+, and CD68+ immune cells in regional lymph node metastases from colorectal cancer as potential prognostic predictors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17(1):25–29. doi: 10.1007/s003840100337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Funada Y, Noguchi T, Kikuchi R, Takeno S, Uchida Y, Gabbert HE. Prognostic significance of CD8+ T cell and macrophage peritumoral infiltration in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10(2):309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prall F, Duhrkop T, Weirich V, Ostwald C, Lenz P, Nizze H, et al. Prognostic role of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage III colorectal cancer with and without microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(7):808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menon AG, Janssen-van Rhijn CM, Morreau H, Putter H, Tollenaar RA, van de Velde CJ, et al. Immune system and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a detailed immunohistochemical analysis. Lab Invest. 2004;84(4):493–501. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313(5795):1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogino S, Galon J, Fuchs CS, Dranoff G. Cancer immunology–analysis of host and tumor factors for personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(12):711–719. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Shibli KI, Donnem T, Al-Saad S, Persson M, Bremnes RM, Busund LT. Prognostic effect of epithelial and stromal lymphocyte infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(16):5220–5227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee HE, Chae SW, Lee YJ, Kim MA, Lee HS, Lee BL, et al. Prognostic implications of type and density of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(10):1704–1711. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsutani T, Shiiba K, Yoshioka T, Tsuruta Y, Suzuki R, Ochi T, et al. Evidence for existence of oligoclonal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and predominant production of T helper 1/T cytotoxic 1 type cytokines in gastric and colorectal tumors. Int J Oncol. 2004;25(1):133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, Ishiwata R, Nagai Y, Fukushima M. The baseline ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes is associated with patient prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2007;73(3–4):215–220. doi: 10.1159/000127412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallina G, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, Colombo MP, et al. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(10):2777–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusmartsev S, Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI. Tumor-associated CD8+ T cell tolerance induced by bone marrow-derived immature myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(7):4583–4592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]