Abstract

Purpose

To characterize continence, satisfaction, and adverse events in women at least 5 years after a Burch urethropexy or fascial sling with longitudinal follow-up of randomized clinical trial participants at least 5 years post-operatively.

Methods

482 (73.6520 (79.4%) of 655 women participated in a randomized surgical trial comparing efficacy of the Burch and sling treatments enrolled in this long-term observational study. Urinary continence status was assessed yearly for a minimum of five years postoperatively. Continence was defined as no urinary leakage on a three-day voiding diary and no self-reported stress incontinence symptoms AND no stress incontinence surgical retreatment.

Results

Incontinent participants were more likely to enroll in the follow-up study than continent patients (85.5% vs. 52.2%), regardless of surgical group (p <0.0001). Overall the continence rates were lower in the Burch urethropexy group than in the fascial sling group (p=0.002). The continence rates at five years were 24.1% (95% CI 18.5% to 29.7%) compared to 30.8% (24.7% to 36.9%), respectively.

Satisfaction at 5 years was related to continence status and higher in women undergoing a sling (83% vs. 73%, p=0.04). Satisfaction declined over time (P=0.001) and remained higher in the sling group (p=0.03). The two groups had similar adverse event rates (10% Burch vs.9 % sling) and similar numbers of participants with adverse events (23 Burch vs. 22 sling).

Conclusions

Continence rates in both groups declined substantially over five years, yet most women reported satisfaction with their continence status. Satisfaction was higher in continent women and those who underwent fascial sling, despite the voiding dysfunction associated with this procedure.

Keywords: Surgical Outcome, Stress Incontinence, Longitudinal Study

Introduction

An ideal goal of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is achievement of long-term continence and low rates of complications. Currently, preoperative counseling of women planning SUI surgery is based on studies with limited follow-up, while surgeons and patients alike would be better served by realistic long-term consequences of the procedure, including continence. Thus, there is an important need for a better characterization of a wide range of outcomes related to SUI surgery over an extended period of time.

The 2011 Cochrane review for traditional sub-urethral slings was limited by availability of studies of “generally short” follow-up ranging from 6–24 months1. However, current evidence suggests that women who undergo Burch urethropexy can expect overall cure rates of 69–88% with a failure rate of 15–20% in the first 5 years after surgery 2,3. A second meta-analysis of 39 studies on SUI surgery, concluded that the long-term effects of this surgery could not be adequately assessed because of the short duration of follow-up in many studies, differences in outcome measures and analytic techniques to deal with subjects lost to follow-up4.

Although midurethral slings are currently the most commonly used SUI surgical procedures, the Burch urethropexy and pubovaginal fascial sling procedures have been studied extensively. We previously reported the two year results the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr), a randomized controlled trial of the Burch urethropexy and the pubovaginal fascial sling5, 6 Recruitment of this cohort of women provided an opportunity to study the long-term effects of SUI surgery. After women enrolled in the SISTEr trial completed that study, they were invited to enroll in a prospective observational study, the Extended-SISTEr study (E-SISTEr). We report the continence status, frequency of, adverse events and self-reported satisfaction of women enrolled in E-SISTEr a minimum of five years after their randomized surgery.

Materials and Methods

The design and primary outcome of the SISTEr trial have been published previously5, 6. Women who completed the clinical trial (assessment of the primary outcome at two years post-surgery) were eligible for the prospective observational study. The observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of all participating institutions. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Participation included a combination of telephone and mail contact every 6 months starting at month 30 post surgery. The primary outcome of continence status was defined by a composite measure consisting of no symptoms of urinary incontinence on a 3-day voiding diary and no self-reported stress urinary incontinence symptoms on the Medical, Epidemiologic, and Social Aspects of Aging Project (MESA) questionnaire (response of “rarely” or “never” for each stress-type symptom) and no surgical retreatment for SUI. Continence was estimated conservatively, when ≥ 1 of the individual components of the outcome was missing but another measure was positive (incontinence), the woman was considered incontinent. When ≥ 1 measure was missing and all other measures indicated continence, the participant was treated as missing and the subject was not considered continent. Other validated questionnaires assessing lower urinary tract symptom distress and impact included the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ)7.

Self-reported treatment satisfaction was assessed with the question, “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the result of bladder surgery related to the following symptoms…..” where response options included: completely dissatisfied, mostly dissatisfied, neutral, mostly satisfied and completely satisfied. Study participants were also queried over the telephone every 6 months performing surveillance for additional SUI treatment including other SUI surgery, tightening of the randomized incontinence sling, collagen injections. Surveillance was also performed to inquire about treatment for persistent or de novo UUI, urinary retention, prolapse and adverse events. Adverse events were categorized by organ system and assigned a severity code according to a modified version of the classification system developed by Dindo and colleagues8.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were compared among the two surgical groups using a two sample t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. The unadjusted continence rates in the two groups at 5 years were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Repeated measures logistic regression models were used to analyze change in treatment satisfaction over time. Available data up to 7 years are shown. All analyses were carried out with SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

Results

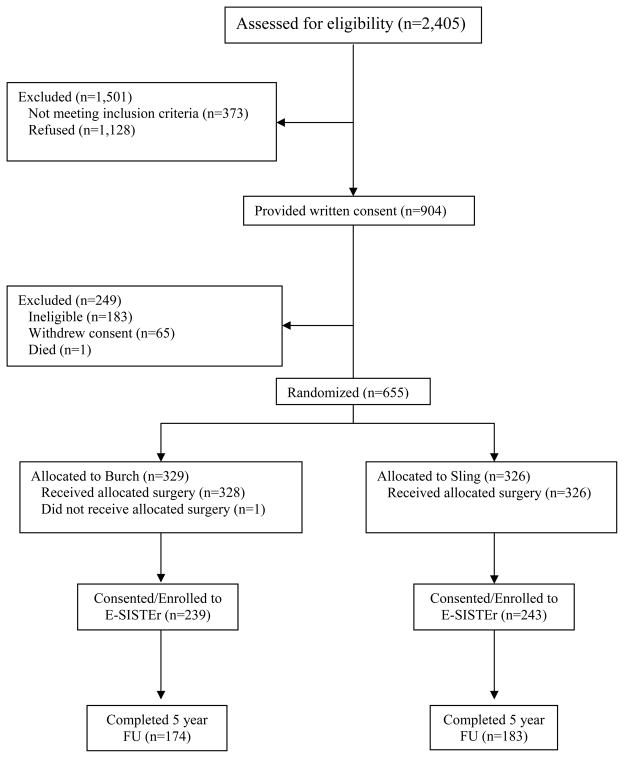

Of the 655 women randomized into SISTEr, 482 (73.6%) were enrolled into E-SISTER. Figure 1 presents patient enrollment and follow-up for the clinical trial and the current prospective observational study. There were no clinically important differences between surgical groups (Burch N=239; sling N=243) in demographic and clinical characteristics at time of enrollment into SISTEr (Table 1). Overall, participants were approximately 53 years old, predominantly Caucasian, parous, and over-weight. Only a minority reported prior incontinence surgery (15%) or were found to have pelvic organ prolapse (POPQ stage III/IV) (17%) during baseline assessment for the SISTEr clinical trial.

Figure 1.

Flow of subjects through SISTEr and E-SISTEr

Table 1.

Selected baseline characteristics of E-SISTEr subjects by randomization group

| Characteristics | Burch (n=239) | Sling (n=243) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age (years): mean (s.d.) | 53.3 (10.5) | 52.3 (9.7) | 0.31 |

| Racial and ethnicity group (%)*: | 0.03 | ||

| Hispanic | 18(8%) | 30(12%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 186(78%) | 179(73%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9(4%) | 19(8%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 25(10%) | 15(6%) | |

| Marital Status (%): | 0.38 | ||

| Not-Married | 68(28%) | 78(32%) | |

| Married/Living as Married | 171(72%) | 165(68%) | |

| Education | 0.90 | ||

| High School or less | 75(31%) | 80(33%) | |

| Some post-HS training | 95(40%) | 92(38%) | |

| Baccalaureate or more | 69(29%) | 71(29%) | |

| Household Income | 0.91 | ||

| <$20,000 | 41(19%) | 39(17%) | |

| $20,000 – $49,999 | 64(30%) | 67(29%) | |

| $50,000 – $79,999 | 45(21%) | 50(22%) | |

| $80,000 + | 63(30%) | 73(32%) | |

| Risk Factors for UI | |||

| BMI: mean (s.d.) | 29.7 (6.3) | 29.9 (5.6) | 0.69 |

| Vaginal Deliveries (%): | 0.19 | ||

| 0 | 21(9%) | 26(11%) | |

| 1–2 | 112(47%) | 94(39%) | |

| 3+ | 106(44%) | 123(51%) | |

| Prior UI surgery (before SISTER) (%): | 0.65 | ||

| No | 201(84%) | 208(86%) | |

| Yes | 38(16%) | 35(14%) | |

| Prolapse (%): | 0.80 | ||

| Stage 0/1 | 53(22%) | 48(20%) | |

| Stage 2 | 1476(61%) | 152(62%) | |

| Stage 3/4 | 40(17%) | 43(18%) | |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Total UDI Score: mean (s.d.) | 151.5 (49.4) | 149.4 (46.1) | 0.62 |

| Total IIQ Score: mean (s.d.) | 172.1 (102.8) | 162.8 (98.3) | 0.31 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Incontinence episodes/day: mean (s.d.) | 3.3 (3.3) | 3.0 (2.7) | 0.29 |

| UI Symptom index£ | |||

| Stress index: mean (s.d.) | 71.7 (16.7) | 70.5 (17.2) | 0.41 |

| Urge index: mean (s.d.) | 36.9 (21.6) | 35.5 (21.5) | 0.46 |

| Q-Tip test (degrees): | |||

| Resting angle: mean (s.d.) | 15.9 (16.8) | 14.8 (17.9) | 0.50 |

| Straining angle: mean (s.d.) | 61.1 (19.2) | 59.7 (17.1) | 0.39 |

| Delta= straining – resting: mean (s.d.) | 45.3 (18.8) | 44.9 (18.2) | 0.83 |

| Any medication for urge or SUI (%) | 0.21 | ||

| No | 183(77%) | 174(72%) | |

| Yes | 56(23%) | 69(28%) | |

| UDS Measures | |||

| Presence of urodynamic stress incontinence (%): | 0.72 | ||

| Yes | 211(91%) | 215(90%) | |

| No | 22(9%) | 25(10%) | |

| VLPP: mean (s.d.) | 114.8 (39.0) | 120.4 (36.2) | 0.21 |

| Delta-VLPP: mean (s.d.) | 78.5 (38.6) | 84.08 (33.8) | 0.19 |

| Detrusor Overactivity (%) | 25(11%) | 16(7%) | 0.11 |

Self-reported

As measured by the MESA questionnaire

BMI- body mass index, UI-urinary incontinence, UDS- urodynamics, VLPP- valsalva leak point pressure. UDI-Urogenital Distress Inventory. IIQ- Incontinence Impact Questionnaire.

E-SISTEr participants were older (mean age 53 vs. 49, p=0.0001), and a higher proportion had at least college education (29% vs. 14%, p=0.005) than SISTEr participants who did not enroll. However, women who were incontinent 24 months after randomized surgery were more likely to enroll in E-SISTEr (85.5%) compared with those who were continent (52.2%), irrespective of assigned surgical group (p <0.0001).

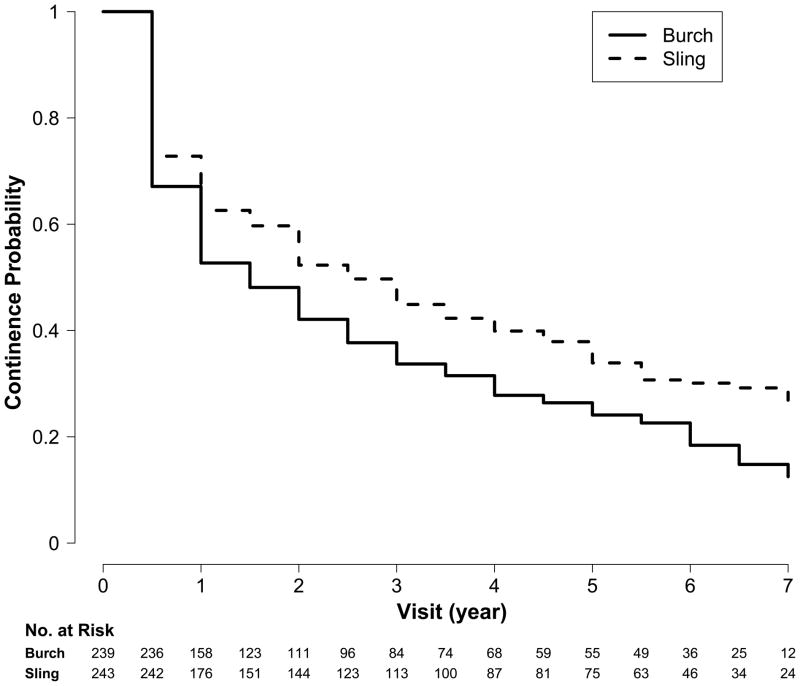

The Kaplan Meier cumulative survival curves for continence rates are significantly different for the Burch urethropexy and fascial sling groups [Log-rank test (Chi-square =10.12, p= 0.002)] as displayed in Figure 2. The continence rates were lower in the Burch urethropexy group than in the fascial sling group as evidenced by the rates at five years: 24.1% (95% CI 18.5% to 29.7%) compared to 30.8% (24.7% to 36.9%), respectively.

Figure 2.

Continence rates over time

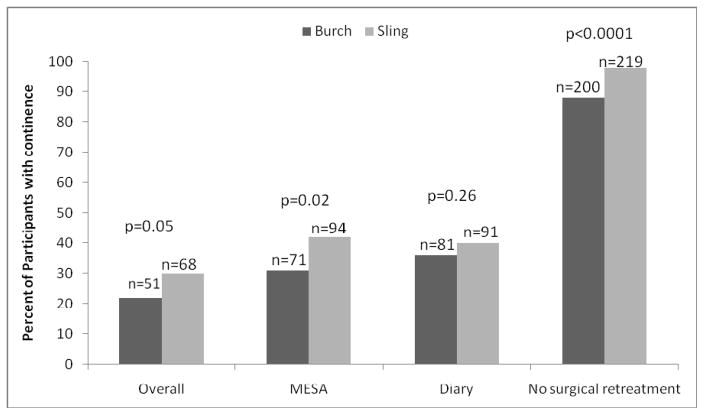

The proportion of continent women by overall composite outcome criteria and by each component of the composite endpoint are represented in Figure 3. Although there was not a clinically or statistically significant important difference in continence status between surgical groups from the 3-day voiding diary, a significantly greater proportion of women in the sling group were continent by self-report on the MESA questionnaire (42% vs. 31%, p=0.02). Fewer women in the fascial sling group experienced surgical retreatment compared to women in the Burch urethropexy group (2% vs. 12%), p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients reporting continence at 5 years by composite criteria and individual outcome components

Note: Other therapy includes medical, device, behavior, and other.

Interestingly, there were no significant differences between the Burch urethropexy and fascial sling groups with regard to lower urinary tract symptom distress at five years post-surgery as measured by UDI scores (50.2 ± 50.9 versus 40.2 ± 45.8, respectively, p=0.05) nor quality of life as measured by IIQ scores (43.1± 68.2 versus 44.8 ± 79.6, respectively, p=0.83). Table 2 displays self-reported treatment satisfaction by randomized surgery group overall and by continence status. A significantly greater proportion of women in the fascial sling group than in the Burch urethropexy group reported satisfaction with their continence status at 5 years (83% vs. 73%, p=0.04). Treatment satisfaction differed by continence status. Almost all continent participants were satisfied; 100% for Burch and 97% for sling. This is in contrast to incontinent women with where the satisfaction rate was 65% for Burch and 75% for sling. As shown in Figure 4, the proportion of women who remained satisfied with treatment declined slightly over time from 24 months to 5 years, i.e. 79% to 73% in the Burch group and 87% to 83% in the sling group. Results of the repeated measures logistic regression models indicated that the change in satisfaction over time was statistically significant (p=0.001) and that satisfaction among participants who received Burch was significantly lower than for those who received the sling (p=0.03). However, the trends over time did not differ significantly between the two treatments (p=0.48).

Table 2.

Satisfaction at 5 year visit

| Burch | Sling | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | N | % | ||

|

| |||||

| 1. All E-SISTEr respondents | 0.04 | ||||

| Satisfied | 126 | 73 | 148 | 83 | |

| Dissatisfied | 46 | 27 | 31 | 17 | |

| 2. Excluding woman with surgical retreatment | |||||

| Satisfied | 115 | 76 | 145 | 83 | 0.13 |

| Dissatisfied | 37 | 24 | 30 | 17 | |

| Total | 152 | 175 | |||

| 3. Assuming those surgically retreated were dissatisfied | |||||

| Satisfied | 115 | 67 | 145 | 81 | 0.003 |

| Dissatisfied | 57 | 33 | 34 | 19 | |

| Total | 172 | 179 | |||

| 4. Stratified by overall success* | |||||

| a. Continence | |||||

| Satisfied | 42 | 100 | 57 | 97 | 0.51 |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| b. Incontinence | |||||

| Satisfied | 84 | 65 | 88 | 75 | 0.10 |

| Dissatisfied | 45 | 35 | 29 | 25 | |

Overall Success was evaluated on or before 5 years; women lost to follow-up and without continence status were excluded.

Figure 4.

The percentage of women who reported being satisfied with their urine leakage after surgery post op.

Treatment for voiding dysfunction was required more frequently in the fascial sling group while treatment for prolapse and urge incontinence occurred with similar frequency in the two groups (Table 3). No serious adverse events were reported in E-SISTEr. Adverse event rates were similar for the two treatment groups: Burch (10%) and sling (9%). There were a total 75 adverse events (38 in Burch and 37 in Sling) in 45 participants (23 in Burch and 22 in sling). Nearly all events (72/75) were recurrent UTI (36 events in 21 Burch patients, 36 events in 21 Sling patients). The other three adverse events occurred in three different women including one case of an exposed suture at the vaginal apex from concomitant prolapse surgery at the time of sling, one case of sacrocolpopexy mesh erosion in a sling patient and an ongoing neuropathy with numbness in the right calf and foot in a Burch patient.

Table 3.

Patients Requiring Treatment for Voiding dysfunction, Urge Incontinence or Prolapse

| Event | Burch # of unique patients | Sling # of unique patients |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| De Novo Urge UI | 7 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Persistent Urge UI | 29 | 33 |

|

| ||

| Prolapse | 5 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Voiding dysfunction* | 1 | 7 |

| Catheter | 1 | 6 |

| Surgery | 0 | 4 |

| Other | 1 | 3 |

Note: The sub-categories under voiding dysfunction represent types of treatment received. A woman could receive more than one treatment

Discussion

These data from well-characterized, randomized trial participants who enrolled into a longitudinal observational cohort clearly demonstrate that continence rates after Burch urethropexy and fascial sling decline steadily during the first 5 years after surgery. Although the rate of decline was similar by surgical group, the higher initial continence rates in the fascial sling group at the onset of E-SISTEr resulted in more continent women at 5 years and subsequently fewer subjects who underwent SUI re-treatment in this group.

The proportion of continent women in this study at 5 years is lower than that reported in previous studies. Ward and Hilton reported a five-year continence rate (based on a negative 1-hour pad test with less than one gram increase in weight)) of 46% of women randomized to Burch colposuspension and 39% in women randomized to tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) 9 Jelovsek et al. reported incontinence rates 4–8 year after randomization to TVT (48%) or laparoscopic Burch (58%)10. In that study, subjects were characterized as continent by a “never” response to the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI) question “How often do you experience urine leakage”. Therefore, it is difficult to compare studies given the variation in outcome measures and definitions of continence. The lower continence rates observed in E-SISTEr are likely related to our use of a composite, unidirectional definition of continence. We and others have shown that composite endpoints are associated with lower continence rates6. The traditional elements in the composite endpoints do not allow for meaningful clinical improvement in symptoms. Also, the unidirectional, “once a failure, always a failure” categorization of continence status is not consistent with current epidemiologic evidence that suggests that continence status can fluctuate 11.

There is likely variation in continence status that depends on patient factors, such as the level of physical activity or the severity of other medical conditions. It is well known that urinary urgency incontinence (UUI) is common in women with stress urinary incontinence, and in fact, most SISTEr participants reported some level of urgency and/or urge incontinence at baseline 12. Even though stress incontinence surgery is not considered a treatment for UUI, many of the outcome measures used to define surgical success do not differentiate between stress and urge incontinent episodes. Thus a patient with persistent urge incontinence would still be considered incontinent, despite resolution of stress incontinence. A significant number of patients, 16%, in both surgical groups, required treatment for urge incontinence in the E-SISTEr trial. This number may not reflect all patients with post-operative incontinence since some may not have sought treatment.

Despite the decline in the proportion of continent women over 5 years, patient satisfaction rates were relatively stable as compared to the 2 year primary outcome time-point (86% fascial sling versus 78% Burch urethropexy)6. The disparity between satisfaction and decreasing continence rates has been reported in other studies and may be due to outcome measures that do not capture “success” from the patient’s perspective, as 63% of women categorized as incontinent were satisfied with their continence status at 5 years13. We found that multiple self -assessment measures of incontinence, including measures of symptom distress and impact, remained markedly improved from baseline despite a statistically significant deterioration of continence rates over the study period. These improvements are likely contributors to the notable satisfaction rates in both groups despite the decreasing continence status.

In addition to factors specific to the individual surgical procedures and the definitional limitations for the primary outcome, long-term continence rates are also influenced by the natural history of the continence mechanism with aging. Epidemiologic data clearly demonstrate that the likelihood of incontinence increases with age. However, we cannot comment on whether the SUI surgeries reduced the proportion of incontinent women compared to similar cohort of women who did not undergo SUI surgery.

We found that incontinent SISTEr participants were more likely to participate in the E-SISTER study, thus biasing the sample toward incontinence over time. It is often assumed that patients with “failed” procedures seek care elsewhere and are therefore less likely to participate in follow-up studies. However, our experience suggests otherwise and may be related to the high level of treatment satisfaction at 2 years or other uncharacterized aspects of the physician-patient relationship. The data in this report are not directly comparable to that of the SISTEr primary outcome paper as the composite outcome in this longitudinal study did not include an objective bladder-fill stress test or a 24 hour pad test which may have further decreased continence rates6.

There were no differences in either serious adverse event (SAE) or adverse event (AE) rates between the two surgical groups in the 5 year period after the index study surgery and were largely related to cystitis type events. Voiding dysfunction continued to occur in this period more almost exclusively in the sling patient population presumably related to new or continuing urge urinary incontinence.

This cohort of randomized women who participated in the E-SISTEr study provided high quality information about the patient’s experience with continence five years after surgery for stress incontinence surgery. The results of this study are robust due to the well-defined surgical cohort, followed closely at multiple centers across the country and assessed by standardized and validated set of measures. Surgical treatments have evolved since this study was designed and implemented. Nonetheless, the findings presented here provide benchmark continence rates using multidimensional/multi-component outcomes for long-term efficacy comparisons of other surgical techniques, such as midurethral slings.

Acknowledgments

Supported by cooperative agreements from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, U01 DK58225, U01 DK58229, U01 DK58234, U01 DK58231, U01 DK60379, U01 DK60380, U01 DK60393, U01 DK60395, U01 DK60397, and 60401 in conjunction with additional support provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Office of Research in Women’s Health, NIH for all aspects of study including design and conduct of the study, data collection, management, analysis and interpretation, as well as manuscript preparation, review and approval.

The authors acknowledge the Yan Xu, MS for her contributions to this analysis. The authors also acknowledge the other investigators of the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network, listed at uitn.org, who participated in the design, conduct, and analysis of these studies.

Abbreviation Key

- SUI

stress urinary incontinence

- SISTEr

Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial

- E-SISTEr

Extended – SISTEr study

- MESA

Medical, Epidemiologic, and Social Aspects of Aging Project

- UDI

Urogenital Distress Inventory

- IIQ

Incontinence Impact Questionnaire

- POPQ

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitation system

- TVT

tension-free vaginal tape

- UUI

urinary urgency incontinence

- SAE

Serious Adverse Event

- AE

Adverse Event

Footnotes

Trial Registration: The randomized trial is NCT00064662 within the registry at clinicaltrials.gov http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rehman H, Bezerra CBC, Bruschini H, et al. Traditional suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001754.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward K, Hilton P, United K, et al. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325:67. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sand PK, Winkler H, Blackhurst DW, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing modified Burch retropubic urethropexy and suburethral sling for treatment of genuine stress incontinence with low-pressure urethra. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novara G, Galfano A, Boscolo-Berto R, et al. Complication rates of tension-free midurethral slings in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing tension-free midurethral tapes to other surgical procedures and different devices. Eur Urol. 2008;53:288–308. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tennstedt S Urinary Incontinence Treatment N. Design of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr) Urol. 2005;66:1213–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albo ME, Richter H, Brubaker L, et al. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2143–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, et al. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: The incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dindo D, Demartines N, Claiven PA. Classification of surgical complications. A new proposal with evlaution in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward KL, Hilton P UK and Ireland TVT Trial, Group. Tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: 5-year follow up. BJOG. 2008;115:226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Karram MM, et al. Randomised trial of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: long-term follow up. BJOG. 2008;115:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lifford KL, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, et al. The epidemiology of urinary incontinence in older women: incidence, progression, and remission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brubaker L, Stoddard A, Richter H, et al. Mixed Incontinence: Comparing Definitions in Women Having Stress Incontinence Surgery. Neurourol Urodynam. 2009;28:268–273. doi: 10.1002/nau.20698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tennstedt SL, Litman HJ, Zimmern P, et al. Quality of life after surgery for stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19:1631–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]