Introduction

Although the obesity epidemic appears to have affected all segments of the U.S. population,1 its impact on children with special health care needs (SHCN) has received little attention. “Children with special health care needs” is a term used in the U.S. to describe children who come to the attention of health care providers and policy makers because they need different services and supports than other children. Government, at both the federal and state levels, has long felt a particular responsibility for safeguarding the health of children with special needs. The definition “children with special health care needs,” in fact, was developed by a work group established by the U.S. Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) to assist states in their efforts to develop community systems of services for children with complex medical and behavioral conditions. According to the MCHB definition:

Children with special health care needs are those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.2

The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, which followed, was the first effort to determine the prevalence of children with SHCH nationwide using a commonly accepted definition (the MCHB definition). This survey estimated that 12.8% of the nation’s children under age eighteen, or about 9.4 million children, have a special health care need.3

Remarkable advances in health care quality and access, and a dramatic broadening of societal opportunities for persons with special needs, have resulted in a marked increase in the number of children with SHCN who live close to normal life spans, and who are in relatively “good health,” despite having an on-going medical condition. Ironically, this remarkable achievement renders this population newly susceptible to secondary conditions associated both with adulthood and with their primary conditions as they grow older. Childhood obesity, because it tends to track into adulthood and is itself a risk factor for the most prevalent chronic diseases, may represent a particular threat to the long-term health of many children with SHCN. Maintenance of a healthy weight in this population is of particular importance because an additional chronic condition, such as type 2 diabetes, may threaten the ability to live independently, or may require a more supervised environment, due to additional demands that accompany disease management. Immediate consequences of excess weight may also make it more difficult for some children to maintain function; for example children with muscular dystrophy who put on excess weight find movement more difficult. Also, because obesity continues to be a highly stigmatized condition,4 it represents another characteristic that identifies a child as “different” from their peers. Although the extent of obesity among children with SHCN as a group is unknown, it is likely that many children with medical conditions or disabilities that affect their activity levels or food intake are at heightened risk for overweight and obesity. (Underweight is a problem for some children as well – it may persist or resolve.) Presumably, children with SHCN are included in prevalence estimates obtained from nationally representative surveys, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys and Youth Risk Behavior Survey, but, as discussed below, this assumption has yet to be verified. Information about risk factors associated with overweight among children with SHCN, including factors that may prevent obesity, is particularly lacking.

The aim of this review is to bring children with special health care needs into the national discussion of the childhood obesity epidemic. In doing so, we seek to understand its impact and to suggest responses to this new health threat facing a group of children who may be particularly vulnerable but have yet to be targeted in widespread efforts to address childhood obesity. Children with SHCN have been identified by the MCHB, state governments, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, among others, as constituting a distinct group of children in need of a coordinated family-centered approach to health care.5 Advocacy efforts and the formulation of health policies at the federal and state level have fostered a network of health services and supports for children with SHCN. Families played a major role in stimulating these reforms and represent a logical and organized constituency with respect to the health promotion needs of these children. The existence of this support network and the policies that sustain it provide an unusual opportunity and also a venue from which to address obesity in this one group of the nation’s children. We approach our review with a social-ecological framework – considering these children and the challenges they face with respect to the maintenance of a healthy weight in the context of their families, schools, health care systems and communities.

This review begins with a profile of children with SHCN. This is followed by an examination of what is known about the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity, first in the general population, and then among children with SHCN. The main body of the review is devoted to an examination, using a social-ecological framework, of how different spheres of influence affect obesity risk factors, primarily in children with SHCN, but referencing the experiences of children in the general population. The review concludes with a discussion including policy recommendations in regard to measures that could help prevent overweight and obesity in this group of children.

Profile of Children with Special Health Care Needs

Children with special health care needs (SHCN) constitute a heterogeneous sub-group of children linked both by the presence of a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and the need for health and related services that differ from those required by children generally in type and in intensity. The federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) promulgated this definition to foster the development of coordinated systems of care capable of addressing the complex and specialized needs of children with chronic health problems and their families, and – by design – the definition is broad and inclusive. Previous approaches to identifying children with chronic health problems, including use of condition lists that categorized children based upon specific medical conditions, such as cerebral palsy, and use of functional status assessments that classified children based upon functional limitations, such as having difficulty walking or seeing, were deemed to have contributed to fragmented, uncoordinated and duplicative health services – problems the new definition was expected to help overcome.6 Although the MCHB definition has been highly effective from policy making and system-building perspectives, its use as a category in surveys makes it difficult to determine the prevalence of particular medical conditions and disabilities among the nation’s children. This is relevant here because overweight is a feature of some medical conditions, and there is very limited published information about the number of children nationwide that these conditions affect.

Despite this limitation, we have elected to use the MCHB terminology – children with SHCN – in this discussion of overweight and obesity in children with chronic health problems, for two reasons. First, this term is used widely in the children’s health field, including in health policy discussions and in recommendations for pediatricians, other primary care providers and families. Second, this term is linked directly to a particular approach to pediatric health care and to health financing mechanisms that affect a sizable population of children and families. The vision of a coordinated approach for safeguarding the health of children with SHCN currently focuses on the provision of health services. There is no reason, however, why this approach could not also encompass efforts to promote healthy weights by addressing lifestyle issues like healthy eating and physical activity. Because population-based information about specific conditions that may be associated with pediatric overweight and obesity is limited, we have used other non-population-based sources, when available. We include, where pertinent, some of what we learned about the challenges children with SHCN face with respect to maintaining healthy weights from eight focus groups we conducted with parents of children with SHCN in five states as part of our formative research for a peer mentoring intervention study.

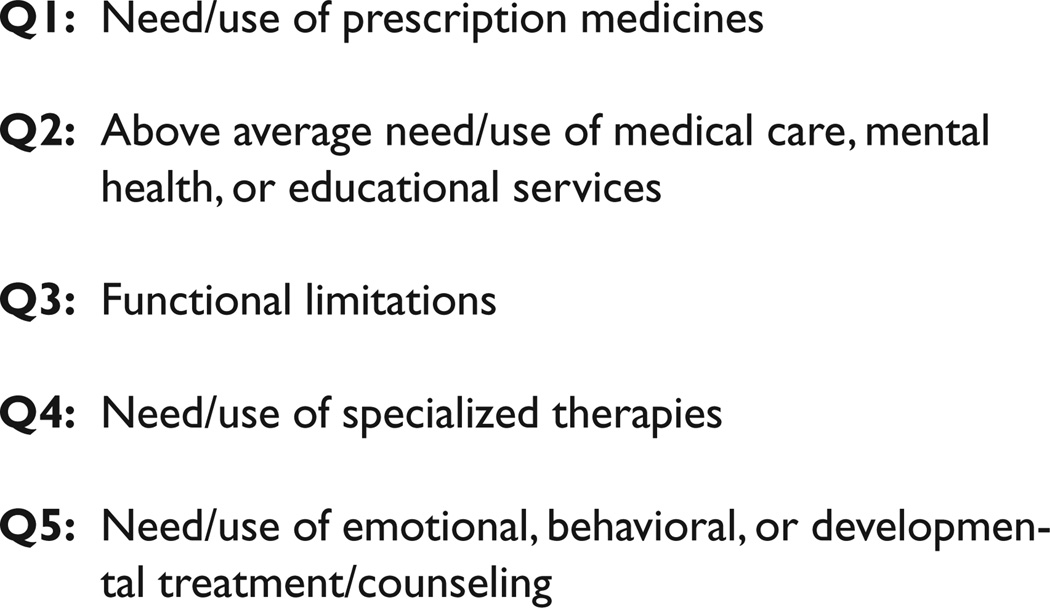

The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs is the primary source of nationally representative information about this population, although this survey does not address topics related to childhood obesity or provide estimates of the prevalence of specific medical conditions or disabilities. This survey was first conducted in 2001 by the National Center for Health Statistics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey (SLAITS) sampling design.7 When households with children under age eighteen were identified, all children in the household were screened for SHCN as follows: Parents who identified a child as having a medical condition of at least one year’s duration were asked five “qualifying” questions about the nature of the child’s health care need (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Five screening questions8 used to identify a child with special health care needs

Responding affirmatively to one of the five questions, in addition to noting that the child’s condition was expected to last twelve months or longer, identified a child as having a “special health care need (Figure 1).” The survey found that almost thirteen percent of children under age eighteen nationwide had a special health care need, and provided detailed descriptive information about these children, including their socio-demographic characteristics, and information about their utilization of health services and the care-taking experiences of their families.

Data from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs make clear that children with SHCN constitute an extremely heterogeneous group. Prevalence varies by gender, age and race/ethnicity, although it does not vary fundamentally by income (Table). Boys are more likely to have a SHCN than girls. Prevalence increases with age, although this may reflect recognition, rather than onset. Large variability across racial/ethnic categories is apparent, with Native Americans/Alaskan Natives with the highest proportion of children with SHCN and Asians the lowest. Although the proportion of specific health care needs overall did not vary across income levels, within certain categories, poor children fared worst. Forty percent of children living in poverty, for example, were reported to need emotional, behavioral, or developmental services, compared to twenty-three percent of children in the highest-income families, while twenty-eight percent were said to have activity limitations compared to seventeen percent in high-income families. When parents were asked to rank the severity of their children’s condition on a scale from zero to ten, where ten is the most severe, the average ranking was 4.2, suggesting moderate severity. When parents were also asked about the degree to which their children’s conditions affect their ability to do things other children of the same age and gender do: twenty-three percent were said to be affected “usually, always, or a great deal” by their conditions. These children represent the subset of children with SHCN with the most serious chronic health problems and disabilities.

Table.

Characteristics of Children with Special Health Care Needs, expressed as percentages (%), unless otherwise indicated

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Males | 15.0 |

| Females | 10.5 |

| Age | |

| 0–5 years | 7.8 |

| 6–11 years | 14.6 |

| 12–17 years | 15.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 14.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.0 |

| Hispanic | 8.5 |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 16.6 |

| Asian | 4.4 |

| Mixed race | 14.2 |

| Poverty status | |

| Below poverty level | 13.6 |

| 1–2 times the poverty level | 13.7 |

| 2–3 times the poverty level | 12.8 |

| >4 times the poverty level | 13.6 |

| Health Care Need | |

| Prescription medicines | 4.3 |

| Medical, mental health, or educational services | 45.6 |

| Emotional, behavioral, developmental services | 28.7 |

| Limitation in the child’s functional abilities relative to peers | 21.3 |

| Use/need for special therapy, such as physical, occupational, or speech therapy | 17.4 |

| Parent-reported severity | 4.2* |

mean on scale of 1 to 10

To supplement this profile and specifically to address the lack of information in the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs about the prevalence of particular medical conditions and disabilities, we are providing recently released prevalence estimates reflecting unweighted frequencies from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Variable Summary for the Sample Child.9 The NHIS is an annual nationally representative cross-sectional household survey conducted continuously by the National Center for Health Statistics to monitor progress toward achieving national health goals. Data are gathered to reflect the experiences of all children, not just children with SHCN. In each household where there was a Sample Child, a knowledgeable adult was asked “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you” that the child had one of a list of different conditions. The sample for the 2005 NHIS included 12,523 children from birth to seventeen years.

We report here the available unweighted frequencies for the responses to select questions, both to depict the range of conditions represented by the term “children with special health care needs,” and to provide rough estimates of the percentage of children nationwide with various conditions and disabilities. (In the few instances where weighted frequencies have been published, they agree well with the unweighted estimates provided herein). Among sample children, about thirteen percent have asthma, seven percent a learning disability (children three to seventeen years old), six percent Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder/Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD/ADD, children two to seventeen years old), 2.5% cerebral palsy, 0.6% mental retardation children (two to seventeen years), 0.5% autism, 0.13% Down syndrome, 0.3% congenital heart disease, and 0.16% diabetes. Almost two percent have an impairment or health problem that limits their ability to crawl, walk, run, or play (lasting more than twelve months for most); just over one percent require special equipment, such as a brace, wheelchair, or hearing aid; just over two percent have trouble seeing, even when wearing glasses or contact lenses; and 0.25% were said to have “a lot of trouble” hearing or to be deaf.

Overweight Prevalence

General Population Estimates and Children with Special Health Care Needs

The current high levels of obesity in American youth have prompted broad concern. Based on the most recent nationally representative U.S. data (2003–2004), 33.6% of children, aged two to nineteen are at risk for overweight (greater than the eighty-fifth percentile BMI) and 17.1% are overweight (greater than the ninety-fifth percentile BMI).10 Estimates from just four years earlier (1999–2000) were 28.2% and 13.9%, respectively. With awareness that these are screening definitions and to avoid unnecessary labeling, the terms at risk for overweight and overweight are generally accepted for the eighty-fifth and ninety-fifth percentiles respectively. We use the term obesity to refer to the overarching concept rather than as a definition, as in “current high levels of obesity.” These nationally-representative obesity prevalence estimates guide the national response to the problem of childhood obesity and are presumed to include children with special health care needs, but specific estimates for this sizeable subgroup of American children are largely unavailable.

Although the sample designs of the large national surveys conducted in the U.S. that are the source of obesity prevalence estimates, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), in no way exclude children with special health care needs, the extent to which they (or their parents on their behalf) elect or are able to participate is not known. Furthermore, children with SHCN who may participate in these surveys are generally not identified as having a “special health care need,” using the definition put forth by the MCHB task force, so the experiences of this group remain invisible. Other characteristics of national surveys may preclude the involvement of children with SHCN. The considerable demands of a protocol such as the NHANES may be unrealistic given the challenges that many parents of children with SHCN face, and it is possible that children with significant behavioral, medical, or physical limitations are not included in proportion to their numbers in the population. Additionally in the NHANES, participants who cannot stand by themselves because of a chronic condition or disability are not measured, and their weight status is thus unavailable.

It is also unlikely that the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), administered by the CDC in partnership with states to monitor health behaviors in high school students includes children with SHCN in proportion to their actual numbers. Children with special health care needs may not participate in school-based surveys like the YRBS because they are attending resource rooms or obtaining special assistance elsewhere when these surveys are administered, and children whose special needs include intellectual disabilities may not comprehend the questions in the YRBS and other self-administered surveys, or be able to complete the survey during the time allocated. The YRBS, for example, is described as having “about a 7th grade reading level.”11

In our own work, which provides, to our knowledge, the only published estimates of overweight in children with disabilities based on nationally representative data, we found ourselves limited to four questionnaire items from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, 1999–2002) that identified children with developmental disorders. We estimated that children with functional limitations in physical activity were more than twice as likely to be overweight (odds ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.7, 3.6) than children without such limitations. Girls identified as having learning disabilities were almost twice as likely to be overweight (95% confidence interval, 1.1, 2.7).12 As discussed earlier, NHANES has several shortcomings with respect to children with SHCN and it is doubtful these findings include children with the most severe disabilities. Nonetheless, these findings, although very incomplete, suggest that, at least for some subgroups, children with SHCN are at equal or elevated risk of overweight compared to the general population.

Estimates of Overweight from Selected Convenience Samples of Children with Specific Medical Conditions and Disabilities

Other estimates of overweight among children with special health care needs are based on non-representative samples and limited to children with specific medical conditions or disabilities. Many are small studies, and the varying sample sizes, select nature of the samples, differences in definitions of overweight, and condition definitions undermine the ability to summarize these reports or to generalize from them to the much larger population of children with SHCN. This section is included to provide the reader with a sampling of what has been published with respect to overweight as it affects different sub-groups of children with SHCN. These examples suggest that children with these particular special health care needs do face risks for overweight and obesity. This sampling also identifies some challenges associated with defining overweight and obesity in children with particular medical conditions and disabilities.

A high prevalence of overweight has long been established for children with specific genetic conditions such as Prader-Willi syndrome,13 Down syndrome,14 and congenital disabilities, such as spina bifida, as discussed below. Conditions including spina bifida,15 Down syndrome, and some types of cerebral palsy result in altered body composition;16 alteration in composition of fat and lean tissue limit the validity of using BMI-derived criteria for overweight. Growth charts for Down syndrome,17 Prader Willi syndrome, Fragile X, and several other rare conditions are available, but have not been constructed to provide useful definitions for overweight.18 A select group of more than five hundred adolescents with intellectual disabilities were screened for obesity at the 1999 and 2001 Special Olympics international games – almost half (forty-five percent) of U.S. participants were found to be at-risk for overweight or were already overweight – this level was four times greater than observed in their non-U.S. counterparts.19 It is noteworthy that standard CDC criteria were used to screen for overweight in this study – despite the fact that many Special Olympics participants are individuals with Down syndrome, whose bodily compositions differ from typically developing children.20 Kristian Holtkamp and colleagues21 evaluated a sample of ninety-seven German boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to test the hypothesis that hyperactive boys would have a lower prevalence of obesity than an age-matched healthy male reference population. Contrary to expectations, they found that a disproportionate number of subjects with ADHD (19.6%) had a BMI greater than or equal to the ninetieth percentile and 7.2% had a BMI greater than or equal to the ninety-seventh percentile. In our chart review of children seen at a specialty clinic, we found that among children with ADHD ages two to nineteen, twenty-nine percent were at risk for being overweight and 17.3% were overweight. For children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, 35.7% were at risk for being overweight, and nineteen percent were categorized as overweight.22 Other studies of children with autism spectrum disorders from Japan and Denmark are inconsistent, with some showing overweight prevalence higher, lower, or similar to rates in the general population.23 A recent report suggested that boys, but not girls, with developmental coordination disorder were at increased risk for overweight.24

A reasonable conclusion from these studies is that the group of children identified as having special health care needs has not escaped the population trend towards higher levels of overweight. An additional conclusion would be recognition that for children with particular special health care needs determining overweight will require new tools or refinements of current tools used for children who are typically developing.

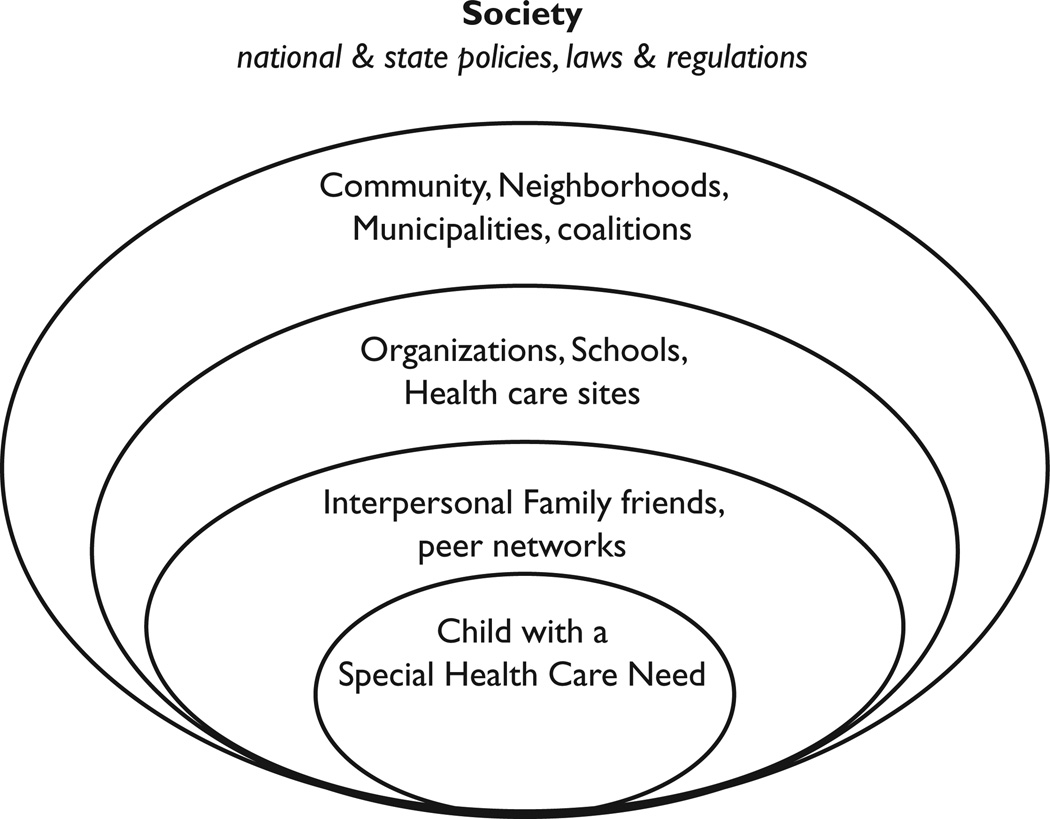

Factors Influencing the Development of Obesity

The social-ecological model provides a useful framework to look at how different spheres of influence affect obesity risk factors, in both children who are typically developing and children with SHCN (see Figure 2). Although the behaviors that give rise to positive energy balance operate at the individual level, the worlds in which children live, play, and learn impact these behaviors both directly and indirectly. In the following sections, we use the social-ecological framework to discuss the factors that may uniquely influence eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviors among children with SHCN. It is important to note that these factors operate in addition to the factors that children experience simply because they are children, and that it is difficult at times to differentiate risk factors associated with the presence of a special health care need from general pediatric risk factors. For this reason, we begin by providing a brief overview of obesity risk factors for children generally, with an emphasis on eating patterns, physical activity, and sedentary behavior, and then move on to discuss the factors that may uniquely influence a child with SHCN with respect to these same behaviors.

Figure.

Spheres of Influences in Childhood Obesity

Key Childhood Obesity Risk Factors in the General Population

Prevention efforts for childhood obesity have focused on food intake and physical activity because overweight results from a positive energy imbalance of energy intake and energy expenditure. Other papers in this symposium discuss the dietary and activity risk factors for childhood obesity.25 In addition, several recent reviews have summarized this large extant literature.26 We focus here on dietary factors, physical activity and sedentary behavior as the key modifiable factors that give rise to overweight in all children, including those with SHCN.

Several dietary factors have been of interest in relation to their known or posited influence on excess energy intake for all children.27 These include soda and other sugar-sweetened beverage consumption,28 skipping breakfast,29 low fruit and vegetable intakes,30 fast food consumption,31 and the proportion of food consumed away from home.32

On the energy expenditure side, low levels of leisure time physical activity in youth and school-based physical education are documented in the general population. Children and adolescents consistently fail to meet current national guidelines for regular physical activity.33 School-based data collected as part of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System indicate that only one in four high school students participated in moderate physical activity for at least thirty minutes at least five days a week preceding the survey, and that fewer than one-third had daily physical education classes.34 The association of low levels of physical activity with the development of higher weights in children was demonstrated in several of the prospective studies we recently reviewed.35

A third area of obesity-risk behaviors for all children is sedentary behavior, which is most often operationalized as screen time – the amount of time children spend watching television, viewing videos, playing video games (on large and small screens), and “working” on the computer. Media use and media multitasking increasingly dominate the lives of young people.36 Screen time is a concern in relation to obesity due to the likelihood that it displaces other activities requiring greater energy expenditure, and because of its association with snacking and exposure to advertising promoting food.37 In addition, frequent mealtime television viewing is associated with lower intake of fruits and vegetables and greater intake of red and processed meats.38 In our recent review of prospective studies in this area, greater amounts of television viewing were related to higher relative weights in youth before adolescence.39

These risk factors now form the basis for the multisectoral action plan, proposed to tackle the prevention of childhood obesity in the U.S. Acknowledging the enormity of the task, short term goals include involvement at all levels to increase availability and use of community recreational facilities, as well as opportunities for play and physical activity, to improve access and affordability of fruits and vegetables, and to implement changes in institutional and environmental policies that promote energy balance.40 However, despite the fact that poor food choice, low level of physical activity, and sedentary behavior are well established and widely accepted as causal in the general population, and that they are likely to operate among children with SHCN as well, they have not received attention with respect to these special populations to date.

Obesity Risk Factors for Children with Special Health Care Needs

As an emerging issue for children with SHCN, there is a dearth of published information about overweight and obesity among children in this group, including information about obesity risk factors. We draw upon multiple and disparate sources in this section. These include published information about clinical features associated with particular conditions seen in some children with SHCN and our focus group research. The section is organized by a series of nested domains of influence, from personal factors to societal influences (see Figure 2).

A. Child/Individual Factors

By definition, children with SHCN have a wide range of chronic health problems and functional impairments/disabilities. Within this highly heterogeneous group are children with relatively rare genetic disorders, such as Prader-Willi syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Cohen syndrome, Borjeson syndrome, Carpenter syndrome, and MOMO syndrome, that include obesity as a clinical feature.41 In addition, the structural phenotypes of certain conditions, such as developmental coordination disorder (or dyspraxia), may result in motor retardation and motor clumsiness, leading to diminished involvement in physical activity.42 It is neither likely, nor is it expected, that the weight status of these children will be addressed in the context of multi-sectoral efforts at obesity prevention.

1. Medication Usage

Medication-induced weight gain is also responsible for a small proportion of the prevalent childhood obesity “cases.” Among these, the atypical antipsychotic medications have received the most attention because the weight gains associated with their use can be substantial. Other drug classes, such as antidepressants, mood stabilizers and anticonvulsants, include specific drugs that have been associated with increased weight.43 Corticosteroids, which are used for a wide range of medical conditions, are of particular concern because other side effects of these drugs include high blood pressure and elevations in blood glucose. Insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents are associated with weight gain as well.44 Risperidone, a commonly prescribed neuroleptic, increasingly used to manage children with autism spectrum disorders, has been associated with weight gain – a side effect that seems to be most pronounced in youth.45 Pharmacotherapy is unlikely to account for a large proportion of pediatric obesity cases; however, the effects on body weight by medications used widely in children may represent an important subgroup of overweight children whose needs are not addressed by population-based obesity prevention efforts. Because nearly seventy-five percent of children with SHCN are known to take at least one prescription drug,46 it is possible that medication-induced weight gain might be a particular issue for children in this group; there is no information at present about the specific medications they take.

Dietary and Activity Behaviors

Little research has been conducted on dietary and activity behaviors that give rise to elevated weight among children with SHCN, and that which has been published is condition- or functional-limitation-specific. By way of example, in one study, youth with physical disabilities were found to have less healthy diets compared with a Canadian national sample. In that study, 101 adolescents with physical disabilities (of whom about half had cerebral palsy) completed the World Health Organization Cross-National Study Questionnaire, which included a limited food frequency questionnaire. Children with physical disabilities more frequently consumed candy and french fries, and consumed fewer servings of low-fat milk products and raw vegetables. A group of subjects in this study indicated that decreased raw vegetable consumption might reflect difficulties chewing or swallowing, and ease of eating less nutritional foods that may be “finger foods.”47 Conditions that are accompanied by difficulty swallowing, like cerebral palsy, are generally associated with poor weight gain, but depending on dietary habits, over-nutrition is also possible.

The dietary behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorders have received considerable attention because they are often characterized by unusual responses to sensory stimuli and abnormalities in eating.48 Children with the condition may be resistant eaters who fixate on certain colors and textures limiting the diversity of their diets and possibly limiting food choices to high calorie-low nutrient meals.49 While these dietary behaviors have yet to be systematically defined, eating patterns among children with these conditions appear to be “abnormal” in ways that would be expected to influence total energy intake. The extent to which these atypical dietary patterns are associated with positive energy balance and the development of overweight in children with autism is worthy of inquiry.

One theme gleaned from our focus group research was that an early need by families to encourage “calories at any cost” as children faced immediate health crises was difficult to replace with more healthful eating patterns when children were older and their health was more stable.50 If this observation has more universal applicability, it suggests that parents and children with SHCN may benefit from guidance around how to change dietary practices as health status improves.

Physical activity may be directly limited for children with certain health care needs as well. Mobility limitations, such as those seen in cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, muscular dystrophy or spina bifida can preclude many activities typically enjoyed by youth. Catherine Steele found that thirty-nine percent of youth with physical disabilities reported never exercising compared to six percent in a national sample. Adolescents with physical disability are four and a half times more likely to exercise only once per week or less when compared to a national sample.51 Children with Down syndrome engaged in less vigorous physical activity and for shorter bouts than their typically developing siblings, based on accelerometry.52 Other conditions, such as developmental coordination disorders or vision or hearing loss may make participation in sports more challenging. Parents in focus groups indicated that certain SHCN, such as cardiac or respiratory conditions, made their child tire more easily.53 The emphasis on competitive activities, especially as children become adolescents, may make it difficult for children with SHCN to be physically active because they may not have the physical prowess to help their team “win.” Time spent watching television or other “screens” may be increased in children with SHCN in order to compensate for time spent not engaged in physical activity – or to provide the needed “downtime.” These sedentary behaviors may also be chosen by children with SHCN as leisure time activities at which they can excel.

B. Interpersonal: Family/Friends/Peer Networks

Although over the course of childhood most children increasingly have more control over their eating and activity patterns, the family exerts major influence on child health behaviors through the options made available, family rules, and parental modeling. Parenting styles have been linked to children’s food intake: overly restrictive and overly permissive approaches have each been shown to negatively impact healthy food choices.54 Authoritarian parenting styles have been linked to increased risk of overweight in first grade.55 The importance of parental modeling was demonstrated by a study showing that children’s fruit and vegetable intake was strongly dependent on maternal intakes of these foods.56 Teachers, friends and peer networks are also major effectors for many children.

1. Family Stressors

In addition to the usual stressors faced by all parents, parents of children with SHCN must address their child’s complex medical needs, perhaps attend behavioral programs or make long trips to and from special schools, engage allied health professional care, obtain referrals for sub-specialty physicians, and fund extraordinary out of pocket health care expenses. In the National Survey of Children with SHCN, parents described some of the challenges their families faced: 20.9% reported that their children’s health care needs created financial problems due to employment issues and out of pocket expenses for supplies and services not covered by insurance. Almost seventeen percent reported having cut back on work, and another 13.2% reported having to stop working to care for their child.57 Time and money needed to arrange for healthy meals, increasing physical activity and reducing screen time may be harder for families also struggling with finances, caretaker time and energy, and pressures associated with employment.

2. Parental Limit-Setting

Parents of children with SHCN may also find it more difficult than other parents to set limits around food choices. Parents in our focus groups indicated that they sometimes felt guilty about the many things their children were unable to do, or that they needed to “pick their battles” with respect to household rules, with the result that healthy eating might be de-emphasized while tooth brushing or a new behavior modification program was emphasized.58 Alternatively, in their desire to have their child “fit in” with their peer group, parents may purchase the foods heavily advertised on television, such as breakfast cereals, or soft drinks, for the child with SHCN’s lunchbox or home pantry. Additionally, the use of foods by parents and/or teachers, particularly energy-dense, low nutrient “junk” foods, as rewards is a common strategy used for behavioral control. This practice may enhance the perceived attractiveness of these foods and may reinforce their desirability – and thereby lead to poor eating habits. In contrast, parents of children with Down syndrome reported use of more restrictive feeding practices with their children with Down syndrome compared to their typically developing siblings.59

3. Family Issues around Physical Activity

Physical activity may be limited for children with SHCN for several reasons that are unique to this population. First, the more limited options that children with mobility limitations have may be further limited by family resources. Adaptive equipment that enables a child with a medical condition or disability to be physically active is an additional expense for families. Furthermore, an activity that particularly suits a child, for example, swimming for a child with a behavioral condition, may require costly pool memberships that are beyond a family’s financial means. Second, parents and/or teachers may be overly protective and discourage participation when it would not be contraindicated. Steele found that sixty-eight percent of interviewed youth with disabilities felt “that their parents stop them from doing what they want to do because they worry too much.”60 Third, many of the opportunities for physical activity in childhood are with other children. To the extent that health conditions result in more social isolation for some children with SHCN, they may be less likely to go out and play with friends after school or in the neighborhood. Finally, children with a range of behavioral problems struggle with peer interactions, and may be excluded from activities with their peers at recess or in other informal settings.

4. Sedentary Behaviors in the Context of Families

Perhaps even more than for parents of typically developing children, parents of many children with SHCN, who often are over-extended by their care-giving responsibilities, may use television and other electronic media to entertain their children and give themselves a needed break. A sizable minority of families have more than one child with a SHCN,61 adding to the burden of child care. Screen time may provide down-time for the child who tires easily. In addition, in our focus group research, parents of children with certain behavioral problems, such as autism spectrum disorders, told us that television and videos provided important social learning that is difficult for the child to obtain through direct peer interaction.62 Video modeling may be more effective than “real” models for children with autism spectrum disorder.63 Particularly compelling was a comment, made by a parent who participated in one of our focus groups that, as a virtual world, cyberspace was for her child the one place where his disability did not matter and could be readily hidden.64 For children with readily apparent disabilities, in cyberspace they are no different from typically developing children.

C. Organizations: Schools, Health Care Sites

The 2004 Institute of Medicine childhood obesity prevention report was a call to action for schools, health care sites, and other organizations to make positive efforts at the proximal behaviors – eating and physical activity – that are responsible for the energy balance that gives rise to obesity in children.65 As a reflection of the urgency for action, that report included the mandate to “take immediate action based on the best available evidence, rather than the best possible evidence.”

1. Schools

Many school systems now serve as venues for interventions, demonstration projects, and curricular reform to address these priorities. The responsibility of states and communities to educate children with disabilities was established during the 1970s, first through federal court rulings, and subsequently through passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (PL 94–142) in 1975, presently enacted as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as amended in 1997.66 A key element of the legislation involves due process protections for children and families; families, by statute, are provided the opportunity to be involved in educational decision-making for their children. Because of these initiatives, most children with disabilities are currently educated in their neighborhood schools in regular classrooms with children who are typically developing, but the extent to which school-based childhood obesity prevention efforts include and/or reach children with special needs is unknown.

We had the opportunity to conduct face-to-face interviews with five special education teachers working in public elementary schools in Somerville, Massachusetts as the teachers completed a community-wide obesity-prevention intervention with a large school-based component.67 As the teachers described it, although they were invited to the teacher-training sessions that were part of the intervention, their ability to incorporate the program elements within their classrooms was highly variable, and they were left to “do the best they could” with un-adapted materials and curricula. The impression of teachers was not that there was any attempt to exclude these children from the intervention activities, but rather that the specialized resources to provide the tailored materials needed were beyond the scope of the project. The extent to which the experiences of these teachers are generalizable is uncertain, but it seems likely that school-wide opportunities implemented as part of school-based interventions may be unavailable for children receiving special education services because of scheduling issues, lack of aides, or lack of adaptive equipment.

The extent to which physical education (PE) classes include children with SHCN or are tailored to meet their needs is also unknown. Based on the CDC’s School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS),68 seventy-five percent of states and school districts have mandatory PE, and while its frequency and make-up is highly variable, physical education classes at a minimum should provide an opportunity for physical activity for all children, including children with SHCN.69

One study of teachers’ attitudes conducted more than twenty years ago found that both regular and adaptive physical education teachers scored below the median on a survey of attitudes toward disabled persons scale.70 National standards for adapted physical education were promulgated more than a decade ago in response to the lack of knowledge among state education leaders.71 Adapted physical education (APE) is physical education that is modified to address the individualized needs of children and youth who have gross motor developmental delays. Other modifications beyond those for gross motor problems may also be needed to address the intellectual and social deficits that some students manifest. The extent of adaptation varies with school system, school, and individual teacher. Although specialized training for physical education teachers in the U.S. exists,72 these programs may be unavailable in schools due to budgetary or personnel constraints. Furthermore, some of the adaptations required may involve special equipment that may exceed financial resources or priorities. Other kinds of modifications may require specialized knowledge and training beyond the scope of most instructors.

As schools respond to the call to serve as a key location for obesity prevention,73 IDEA could be used to advocate for inclusion of all enrolled children – even those in special education classrooms, or with modified schedules, in physical education as well as in new curricula and programming designed for obesity prevention. Individual parents could also advocate for the inclusion of their child in such efforts through provisions of the child’s Individual Education Plan (IEP), the child-specific blueprint for educational programming.

A second law enacted in 2004, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004,74 included a requirement for a Local Wellness Policy. Section 204 requires all public schools that participate in the national school lunch program have a written policy that (at a minimum) includes goals for nutrition education, physical activity, and other school-based activities designed to promote student wellness in a manner that the local educational agency determines is appropriate. Childhood obesity was specifically included in the legislation: localities must have written nutrition guidelines for all food available on each school campus during the school day with the objectives of promoting student health and reducing childhood obesity. Also stated was the obligation to involve parents, students, school representatives, and the public in the development of the policy. Model school wellness policies developed by the National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity75 make specific reference to children with SHCN in relation to during- and after-school physical education. The law took effect June 30, 2006, so it is not yet clear how adherence to it will be monitored. The new policy and specific guidance on how it should be developed could serve as a vehicle to bring parents and teachers of children with SHCN into school-wide discussions of health and wellness.

2. Health Care Services

Physicians have an important role in monitoring children with respect to healthy weights and in counseling parents about the importance of healthy eating and regular physical activity. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ policy on pediatric obesity prevention calls for physicians to screen all children and adolescents annually for excessive weight gain.76 A recent study, however, found that preventive screening for weight occurs at fewer than one-fifth of well-child health supervision visits within the general population.77 Varying rates of counseling by childhood age group were observed in the areas of maintenance of a healthy weight (49–56%), eating a healthful diet (62–71%), and physical activity (41–59%).78 The policy also calls on pediatricians to identify and track patients at risk for weight gain by virtue of family history, birth weight, and socioeconomic, ethnic, cultural, or environmental factors.79

There is no published information about the degree to which children with SHCN receive preventive screening or anticipatory guidance for weight, but it is likely to be even more limited than in the general population – despite the fact that most children with SHCN have access to health care services. According to the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs,80 eighty-eight percent of children were reported to have health insurance coverage for all of the previous year; just twelve percent were uninsured for all or part of that year, and ninety-two percent had a “usual source of sick care.” For almost three-quarters of children surveyed, this source was a private doctor’s office. Despite access, however, some children with SHCN, e.g., a child in a wheelchair, may not be able to be weighed on the scale in a physician’s office. A more fundamental barrier to children with SHCN receiving routine preventive screening is likely the fact that efforts to improve the quality of health services for this group have focused historically on the provision of specialty medical care. Beginning with Title V of the Social Security Act of 1935, the federal government, in partnership with state health departments, assumed responsibility for meeting the needs of children with physical disabilities by providing specialty physicians’ services through the Crippled Children’s Services Program.81 At present, many children with SHCN see sub-specialists, not primary care providers, for their usual source of care, and routine preventive services are typically not within the sub-specialist’s realm of responsibility. According to Bonnie Strickland et al,82 “Although children with SHCN often receive excellent specialty care, evidence suggests that routine health care often is overlooked, and some basic primary care for children with SHCN can be missing.” Preventive weight screening would fall into this category.

More recent policy initiatives promise to extend routine preventive services, including preventive screening for weight and counseling to parents about healthy eating and physical activity, to children with SHCN. The “medical home” initiative that began in 1994 as a collaborative effort between the MCHB and the American Academy of Pediatrics, shifted the policy emphasis from ensuring access to particular kinds of specialty medical care to finding new ways to ensure children receive care that is coordinated, ongoing, and family-centered. A “medical home” has been defined as a “…convenient, reliable source for comprehensive care where families are welcomed and encouraged to be involved in their child’s care and where comprehensive services are provided and coordinated.”83 Efforts to ensure medical homes for children with SHCN are relevant to this discussion, because physician-based efforts to promote healthy weights and prevent obesity are best placed within the context of health care services that are family-centered, coordinated and include “well child care.”

Health professionals may not always encourage limit setting by parents of children with SHCN. In our focus group research, parents indicated that health care providers rarely initiated discussions about healthy eating and physical activity patterns and were not viewed as responsive to parents’ concerns and questions in this area. In fact, parents told us that, in their experience, physicians brushed off their concerns about eating habits, in particular.84

In an initiative designed to support health professionals in their efforts to promote health and wellness for all children, the Maternal and Child Bureau, in collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics, developed Bright Futures Guidelines for the Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents in 1989, defined as a “vision, philosophy, set of expert guidelines, and a practical developmental approach to providing health supervision for children of all ages.”85

Bright Futures is a set of principles, strategies and tools that are theory-based, evidence-driven, and systems-oriented that can be used by health professionals to improve the health and well-being of all children through culturally appropriate interventions that address their current and emerging health promotion needs at the family, clinical practice, community, health system, and policy levels.86 In addition to the basic document Bright Futures, a collection of materials for professionals has been developed in key areas such as nutrition, oral health, physical fitness, and mental health. Organized around developmental periods (infancy, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence), the focus on prevention provides clear roles for families, schools, health providers and communities. The American Academy of Pediatrics, now the home of Bright Futures under contract with MCHB, is presently updating and revising Bright Futures. The revision, which is scheduled to be released by Spring, 2007, includes more substantive inclusion of children with SHCN.

D. Communities: Neighborhoods, municipalities, coalitions

Communities play a key role in obesity prevention as social environments and physical environments. The degree to which community organizations are prepared to accommodate the diverse needs of children with SHCN, particularly with respect to physical activity, appears to be variable. Parents in our focus groups related both positive and negative experiences enrolling their children in programs run by local community groups.87 As discussed above, family and peer factors both common to all children and unique to children with SHCN influence the individual child’s participation in team sports.

Many municipalities provide summer programs for children, including recreational programs, city pools, and community gardens. As community organizations, neighborhood groups, cities, and towns work to improve the physical activity opportunities in their locales, consideration of access and inclusion of all groups is possible, but not ensured. The importance of a community’s built environment in encouraging activity is increasingly recognized.88 The often cited example of how mandated curb cuts for accessibility has benefited cyclists, skaters, skateboarders and mothers with baby carriages suggests that consideration of more inclusive design may reap unexpected rewards for all community residents. Several national organizations are dedicated to advocating for inclusive design and inclusive programming. Organizations such as the National Center on Physical Activity and Disability provide resources on recreational access rights, model “inclusion” communities, self-advocacy, guidance for parents, and many other relevant areas.89 Other programs, like BAM90 and I Can Do It, You Can Do It91 are devoted to children with physical limitations. Communities may make an affirmative effort at inclusion. For example, Prince George’s County in Maryland provides extensive programming, equipment, and accommodation to its residents. Services include adapted equipment, large print/Braille, sign language interpreters, assistive listening devices, audio description, staff consultations, as well as inclusion support staff and volunteers. In addition, they conduct ongoing staff training on disability characteristics, disability etiquette, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The welcoming environment that these services create for children with SHCN can be instrumental in broadening participation. Community recreational activities manned by volunteers who are not comfortable and/or skilled in working with children with SHCN and who lack access to the kind of training opportunities provided in Prince George’s County, may not be perceived as welcoming by children with SHCN and their families.

Bringing Children with SHCN into the National Response to Childhood Obesity

Within the U.S, children with special health care needs (SHCN) have made impressive gains in the past two decades, thanks largely to societal-wide efforts to broaden opportunities for all individuals with special needs, but due also to particular efforts to promote and protect the health of children with SHCN. These efforts have primarily involved ensuring financial access to quality health care services and the model of pediatric health care, called the “medical home,” designed to meet their needs for comprehensive, coordinated, reliable and family-centered care. Currently, the majority of children with SHCN live close to normal life spans, almost all have a usual source of health care, and most are in “good health” all or most of the time. The obesity epidemic currently affecting children nationwide has the potential to slow the advances that children with SHCN have been making with respect to health. Currently, there are no data from nationally representative sources to determine the impact of the rising prevalence of pediatric obesity on children with SHCN, but the limited data suggest these children are not protected from the forces associated with increasing childhood overweight and obesity in the general population. To our knowledge, societal concerns in regard to increases in childhood overweight and obesity have not yet been voiced loudly within the formal network of services and supports that exist for the 9.4 million children with SHCN in the U.S.

In this paper we assert that children with SHCN as a group face at least the same level of risk for overweight and obesity as children who are typically developing, and it is likely that some children with SHCN face elevated risks, although the nature of these risks is currently not well understood. Acting pre-emptively to promote healthy weights in children with SHCN by routine weight monitoring and by providing parents with anticipatory guidance and support with respect to healthy eating, physical activity and sedentary behavior is a timely and important investment in the health of these children. The organized network of health services that support children with SHCN and their families, and the formal role of family organizations within this network provides an infrastructure that is unusually well-poised to address risk factors associated with childhood overweight. The role of families is particularly appropriate because the proximal health behaviors related to childhood obesity – healthy eating, physical activity and sedentary behavior – are in the domain of family responsibilities and occur largely in the context of the home. Our focus here is on multi-sectoral efforts to promote healthy weights in all children and not on those children with SHCN where obesity is a clinical feature such as Prader-Willi. We understand that families with children whose medical conditions are unstable or families that are still searching for skilled health care providers for their children need to remain focused on those issues and not on issues related to health and wellness.

In our focus group research, it is striking that many families of children with SHCN saw family-based health and wellness activities, like promoting children’s healthy weights, as even more important for their children with SHCN than for their children who were typically developing.92 These parents were listening to the ongoing national discussion about childhood overweight and obesity, and thinking about how it affects their children with SHCN.

The challenge moving forward is to convince health care providers, child health advocates, policy makers and families overall that overweight and obesity are a threat to children with SHCN, and to enlist their help in working with families and communities to reduce the risks these children are facing. Children with SHCN are first and foremost children, and efforts must be made to ensure they are reached by population-based efforts to prevent obesity via initiatives directed towards families, pediatricians and other health care providers, schools, communities and the media. Simultaneously, efforts must be made to address issues specific to children with SHCN that place them at elevated risk for obesity. Children with SHCN present with a wide range of health problems and disabilities; efforts to promote healthy weights and prevent obesity in this group must similarly be varied.

As a first step, there is a need for information from a nationally representative sample of children with special health care needs on this issue. Optimally, these data would include information about the prevalence of overweight and obesity and about their associated risk factors. Ideally, these data would also include information about specific medical conditions and disabilities and their associations with health behaviors linked to weight gain, although these data may be hard to come by in surveys utilizing the MCHB definition – “children with special health care needs.” This difficulty could be addressed by the addition of the five screening questions (Figure 1) used in the National Survey of Children with SHCN to ongoing surveys, such as the NHANES. Newly developed instruments will be needed to investigate the role that medications associated with weight gain, directly or indirectly, may play with respect to overweight and obesity in children with SHCN. According to the National Survey of Children with SHCN, 74.3% of children with SHCN take at least one prescription medication.93 It is possible that at least some of the estimates of overweight and obesity we reported, which were based on non-representative samples involving children with specific conditions and disabilities, reflected the child’s use of medications that stimulated their appetites or made them lethargic or otherwise associated with weight gain.

The standard growth reference and screening guidelines94 based on BMI are appropriate to define overweight for the majority of children with SHCN. Children with short stature, however, may not be covered by these charts. For conditions characterized by altered body composition, such as spina bifida and Down syndrome, BMI is not a valid measure on which to establish a definition.

It is also essential that the network of health services and supports for children with SHCN assume more responsibility for routine weight monitoring and for counseling parents about the need for healthy eating and regular physical activities – despite their special health care need or perhaps more importantly because of it. The fact that many children with SHCH see sub-specialists as their usual source of care is potentially problematic because routine preventive practices, like weight monitoring, are typically not a responsibility of the sub-specialist. Nonetheless, the “medical home” and Bright Futures initiatives, both based at the American Academy of Pediatrics, hold great promise for supporting the nation’s pediatricians, including those managing the care of children with SHCN, in their efforts to promote healthy weights and prevent childhood obesity among their young patients. Parents could benefit particularly from guidance around changing dietary patterns/practices in response to changes in their children’s health status. Parents in our focus groups voiced the need for guidance from their children’s doctors about realistic levels of physical activity given their child’s medical condition and need for regular physical activity.95

Children with SHCN must also be included routinely in multi-sectoral efforts to prevent obesity at other places in the community, including school recreational programs and media activities. The degree to which school-based childhood obesity prevention efforts currently include and/or reach children with special needs is unknown. We learned in our own work with special education teachers participating in the school-based component of a community-wide obesity prevention initiative that children with SHCN were not necessarily excluded from obesity prevention activities, but neither did they participate routinely. This was largely because the extra support required to accommodate students with special needs in these activities was not provided to teachers.

Section 204 of the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act, which took effect in June, 2006, presents another opportunity to include children with SHCN in the national response to the obesity epidemic.96 The law will greatly increase the number of schools nationwide with programs designed to promote healthy eating and physical activity among students. Model policies developed by the National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity, intended to support the legislation, make specific reference to children with SHCN in relation to during-and after-school physical education, and could serve as a platform for advocacy efforts.

The legal protections granting all children, including children with special needs, the right to a free and appropriate public education could be extended to protect the right of children with SHCN to participate in health and wellness activities centered in schools. As obesity prevention initiatives increasingly become part of the public school experience, research is needed to examine potential barriers to participation by children with SHCN (e.g., perhaps attitudinal or financial barriers, or concerns on the part of health professionals and school administrators about medical risks or liability issues related to the child’s medical condition or disability), and how these barriers can be overcome.

The Family Opportunity Act, federal legislation passed in February, 2006, contains language to support the establishment of funded Family-to-Family Health Information Centers across the U.S., for families of children with special health care needs and disabilities, in partnership with state organizations.97 Approximately half of the states now have Family Opportunity Act funding. Although the goal of this legislation is to help families gain insurance access and to maneuver more effectively through health insurance policy provisions, at least one state, Washington, has included activities to support families by providing information about health and wellness. If other states follow Washington’s example, more families across the country could be connected to local resources. This represents an exciting potential venue to promote health and wellness to families.

The media environment also exerts a powerful influence in the lives of contemporary children,98 including children with SHCN. Limited research suggests that children with SHCN are not regularly targeted in media, such as magazines and television programs. Hardin et al. found that only 0.3% of the advertising and editorial photos in a three-year time span in Sports Illustrated for Kids included persons with disabilities.99 The known importance of role models for sound development would suggest the need for children and adults with physical, intellectual, and behavioral/emotional disabilities to be portrayed in a positive light in mainstream media. This approach would serve to encourage children with SHCN to take more active roles in physical activities and sports.

As the nation’s attention turns increasingly to preventing overweight and obesity in children, more community-based activities designed to promote healthy eating and regular physical activity will become available. Children with special health care needs must not only be able to participate in these activities but they must be encouraged to do so. The network of services and supports designed to promote the health of children with special health care needs must also embrace this issue and take steps to support families in these areas, so that the remarkable gains in life expectancy are not lost to preventable secondary conditions.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. Obesity Research. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, Lauver C, McManus M, Newacheck PW, Perrin JM, Shonkoff JP, Strickland B. A New Definition of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:137–140. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs: Chartbook 2001. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Health Resources and Services Administration and Maternal and Child Health Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen I. Associations between Overweight and Obesity with Bullying Behaviors in School-Aged Children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1187–1194. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Strauss RS, Pollack H. Social Marginalization of Overweight Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:746–752. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perrin EC, Newacheck P, Pless IB, Drotar D, Gortmaker SL, Leventhal J, Perrin JM, Stein REK, Walker DK, Weitzman M. Issues Involved in the Definition and Classification of Chronic Health Conditions. Pediatrics. 1993;91:787–793. supra note 2.

- 6.Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, Perrin JM, McPherson M, McManus M, Lauver C, Fox H, Arango P. An Epidemiologic Profile of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:117–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs: Methodology Report Number 41. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Health Resources and Services Administration and Maternal and Child Health Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying Children with Special Health Care Needs: Development and Evaluation of a Short Screening Tool. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2002;2:38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC Wonder. 2005 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Variable Summary for the Sample Child. [last visited December 5, 2006]; at < http://aepo-xdv-www.epo.cdc.gov/wonder/sci_data/surveys/nhis/type_txt/nhis2005/samchild_freq.pdf>.

- 10.Supra note 1.

- 11.Kolbe LJ, Kann L, Collins JL. Overview of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Public Health Reports. 1993;108:2–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandini LG, Curtin C, Hamad C, Tybor DJ, Must A. Prevalence of Overweight in Children with Developmental Disorders in the Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. Journal Of Pediatrics. 2005;146:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, Greenswag LR, Whitman BY, Greenberg F. Prader-Willi Syndrome – Consensus Diagnostic-Criteria. Pediatrics. 1993;91:398–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chumlea WC, Cronk CE. Overweight among Children with Trisomy 21. Journal Of Mental Deficiency Research. 1981;25:275–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1981.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes-Allen MC, Tring FC. Obesity - Another Hazard for Spina-Bifida Children. British Journal of Preventive & Social Medicine. 1973;27:192–196. doi: 10.1136/jech.27.3.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trueth MS, Bandini LG. Regulation of Body Weight: Energy Expenditure and Physical Activity. In: Goran MI, Sothern MS, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Obesity. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Styles ME, Cole TJ, Dennis J, Preece MA. New Cross Sectional Stature, Weight, and Head Circumference References for Down’s Syndrome in the UK and Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:104–108. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.2.104. supra note 14.

- 18.Ekvall SW, Bandini LG, Ekvall V, Curtin C. Obesity. In: Ekvall SW, editor. Pediatric Nutrition in Chronic Diseases and Developmental Disorders, Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Oxford University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris N, Rosenberg A, Jangda S, O’Brien K, Gallagher ML. Prevalence of Obesity in International Special Olympic Athletes as Determined by Body Mass Index. Journal of The American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:235–237. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luke A, Roizen NJ, Sutton M, Schoeller DA. Energy Expenditure in Children with Down Syndrome: Correcting Metabolic Rate for Movement. Journal of Pediatrics. 1994;125(no. 5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70087-7. Pt. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtkamp K, Konrad K, Muller B, Heussen N, Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Hebebrand J. Overweight and Obesity in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:685–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtin C, Bandini LG, Perrin EC, Tybor DJ, Must A. Prevalence of Overweight in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Chart Review. BMC Pediatrics. 2005;5:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-5-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiteley P, Dodou K, Todd L, Shattock P. Body Mass Index of Children from the United Kingdom Diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Pediatrics International. 2004;46:531–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Takeuchi E. Incidence of Obesity among School-Children with Mental Retardation in Japan. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1994;99:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sugiyama T. A Research of Obesity in Autism. Japanese Journal on Developmental Disabilities. 1991;13:53–58. [Google Scholar]; Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T. Body Mass Index in Male and Female Children with Infantile Autism. Autism. 2002;6:197–205. doi: 10.1177/1362361302006002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cairney J, Hay JA, Faught BE, Hawes R. Developmental Coordination Disorder and Overweight and Obesity in Children Aged 9–14 y. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:369–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brownell K. Obesogenic Environment. Journal of Law and Medicine & Ethics. 2007;35(no. 1) doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00114.x. XXXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Newby PK. Is Diet Associated with Childhood Obesity? A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Journal of Law and Medical Ethics. 2007;35(no. 1) doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00112.x. XXXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Peterson KE, Fox MK. School Based Interventions. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2007;35(no. 1) doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00116.x. XXXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in Children and Young People: A Crisis in Public Health. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5:4–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood Obesity: Public-Health Crisis, Common Sense Cure. The Lancet. 2002;360:473–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Must A, Tybor DJ. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior: A Review of Longitudinal Studies of Weight and Adiposity in Youth. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:S84–S96. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherry B. Food Behaviors and Other Strategies to Prevent and Treat Pediatric Overweight. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:S116–S126. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between Consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and Childhood Obesity: A Prospective, Observational Analysis. The Lancet. 2001;357:505–508. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkey CS, Rockett HRH, Gillman MW, Field AE, Colditz GA. Longitudinal Study of Skipping Breakfast and Weight Change in Adolescents. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krebs-Smith SM, Cook DA, Subar AF, Cleveland L, Friday J, Kahle LL. Fruit and Vegetable Intakes of Children and Adolescents in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:81–86. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170260085014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pesa JA, Turner LW. Fruit and Vegetable intake and Weight-Control Behaviors among US Youth. American Journal Of Health Behavior. 2001;25:3–9. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.French SA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast Food Restaurant Use among Adolescents: Associations with Nutrient Intake, Food Choices, and Behavioral and Psychosocial Variables. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25:1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin BH, Guthrie J, Frazao E. Quality of Children’s Diets at and away from Home: 1994–1996. Food Review. 1999;22:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1996. [Google Scholar]; Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in Physical Activity Patterns in the United States, by Sex and Cross-Sectional Age. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2000;32:1601–1609. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey 1999. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Must A. supra note 26.

- 36.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8–18 Year-Olds. Menlo Park: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, Varady A, Robinson TN. Children’s Food Consumption during Television Viewing. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of Television During Meals and Children’s Food Consumption Patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e7. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Must A. supra note 26.