Abstract

Considerable research has documented associations between adverse life events and internalizing symptoms in adolescents, but much of this research has focused on the number of events experienced, with less attention to the ecological context or timing of events. This study examined life events in three ecological domains relevant to adolescents (i.e., family, peers, themselves) as predictors of the course of depressive symptoms among a community epidemiologically defined sample of 419 (47.2% females) urban African American adolescents. Given that youth depressive symptoms change over time, grade level was examined as a moderator. For males, the strength of associations between life events happening to participants, family life events, and peer life events and depressive symptoms did not change from grades 6–9. For females, the strength of the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms did not change over time, but the strength of associations between life events happening to participants and family life events and females’ depressive symptoms decreased over time. Implications of the findings and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Depression, Stressors, Inner-city/urban, African American

Introduction

The association between experiences of adverse life events and depressive symptoms in youth has been well-established (Cardemil et al. 2007; Cicchetti and Toth 1998; Deardorff et al. 2003; Hankin and Abramson 2001). Life event stress has been linked with youth depressive symptoms in cross-sectional and prospective studies, and there is evidence that life events predict the developmental course of depressive symptoms (Garber et al. 2002; Ge et al. 1994). In general, this research has examined the number of life events that youth experience without careful examination of the type of life events experienced. Because the salience of life events may vary based on the ecological domain in which these events occur, it is important to examine not only the frequency with which life events occur, but also the ecological domain in which they occur. In addition, the timing of these life events is important, as there is evidence that the prevalence of youth depressive symptoms changes over time, which may be due in part to experiences of adverse life events (Cole et al. 2002; DuBois et al. 1995). Furthermore, much of the current research examining the association between life event stress and youth depressive symptoms has included predominately Caucasian and middle-class samples (Franko et al. 2004; Hammack 2003; Roberts and Sobhan 1992). Thus, it is not clear whether African American youth from low-income urban settings respond similarly to exposure to adverse life events. The present study addresses these issues in the existing literature by examining longitudinal associations between urban African American adolescents’ experiences of adverse life events in three ecological domains (i.e., life events that happen to the adolescents, their family members, and their peers) and depressive symptoms. The present study aims to address two primary research questions: (1) Do family life events, peer life events and/or life events happening to participants predict depressive symptoms in adolescence? and (2) Does the strength of the association between family life events, peer life events and/or life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms change as a function of time?

Adverse Life Events and Depressive Symptoms

Research repeatedly has shown that the more negative life events youth experience, the greater their risk of developing depressive symptoms (Cicchetti and Toth 1998; Hankin and Abramson 2001). Life event stress is associated not only with increases in depressive symptoms but also with depressive syndromes and disorders in adolescents (Cardemil et al. 2007; Cicchetti and Toth 1998; Compas et al. 1994; Deardorff et al. 2003; Hankin and Abramson 2001). Patton et al. (2003) found that adolescents who experienced one negative life event had a five-fold increase in the odds of developing stable depressive disorders compared to controls; those who experienced multiple life events had an eight-fold increase in risk of developing stable depressive disorders (Patton et al. 2003). These findings suggest that exposure to adverse life events can place youth at significant risk for developing depressive symptoms and disorders.

Low-income, urban, African American youth’s disproportionate exposure to adverse life events in multiple domains (e.g., life events that one experiences, life events happening to family members, life events happening to peers) places them at increased risk of experiencing adjustment difficulties in response to these stressors (Attar et al. 1994; Deardorff et al. 2003). However, few studies have examined the association between life event stress and depressive symptoms in this population, or whether the impact of life events on depressive symptoms varies according to the ecological domain in which they occur. Some research with minority youth has found significant cross-sectional and prospective associations between adverse life events and depression (e.g., Deardorff et al. 2003; Hammack et al. 2004). For example, Deardorff et al. (2003) found that experiences of adverse life events were positively correlated with depressive symptoms in their sample of ethnically diverse, urban youth. Natsuaki et al. (2007) found that for their sample of African American youth, stressful life events experienced at age 11 predicted depressive symptoms at age 13. While these studies examined cumulative life event stress (i.e., based on frequency of life events), little work has examined how the impact of adverse life events on depressive symptoms may vary based on the ecological domain in which the life events occur. Because of urban, African American adolescents’ unique ecological niche in society, such as residing in dangerous contexts, more careful examination of how life events across ecological domains impact depressive symptom development in this understudied population is warranted.

Importance of Ecological Domain of Life Event Stress

Research examining the link between life event stress and depressive symptoms has typically focused on the number of life events experienced, with less attention to the ecological domain in which life events occur (Cicchetti and Toth 1998; Compas et al. 1994; Hankin and Abramson 2001). Focusing on the number of life events experienced is consistent with cumulative stress models suggesting that the more stress exposure youth have, the greater adjustment difficulties they experience, including depressive and aggressive symptoms (Morales and Guerra 2006). Although examining the role of cumulative stress on youth’s depressive symptoms can be informative, this approach does not provide information regarding the degree to which specific types of life events are associated with particular outcomes (e.g., youth depressive symptoms) (Grant et al. 2003).

According to Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) Ecological Systems Theory, multiple levels of a youth’s ecology (e.g., family, peers) interact to influence youth development. Similarly, the ecological transactional model suggests that multiple ecological factors can influence the emergence of depression in adolescents depending of how proximal the influence is to the individual (Cicchetti and Toth 1998). These ecological theories suggest that the ecological levels at which life events occur are important for understanding youth developmental outcomes. By examining life events occurring at ecological domains that are “proximal” to the individual, namely events involving family members, close friends, and themselves, it will be possible to gain a better understanding of the specific types of life event stress that impact the development of adolescents’ depressive symptoms. In fact, there is some evidence that life events in different ecological domains differentially impact youth’s psychological adjustment. For example, research has shown that while adolescents who are more reactive to stressful events involving others are more likely to exhibit internalizing symptoms, adolescents who are more reactive to stressful events involving threats to their sense of self are more likely to exhibit both externalizing and internalizing syndromes (Leadbeater et al. 1995). This research suggests that there is some variability in youth’s responses to experiences of adverse life events depending on the ecological domain in which those events occur.

Examining ecological domains of adverse life events also may increase our understanding of gender differences in youth depression. Research suggests that gender differences in prevalence rates and severity of depression begin to emerge during early adolescence (Abela and Sullivan 2003; Shih et al. 2006) and this gender difference in depression may be due, in part, to gender differences in exposure to stress. For example, Shih et al. (2006) found that females experienced significantly more episodic stressful life events, particularly interpersonal stressors, than do males and this difference in stress exposure explained 36% of the gender difference in depression rates in their sample (Shih et al. 2006). Thus, by examining the role of life events in multiple ecological domains, researchers can develop a better understanding of how the context in which life events occur impact youth psychological adjustment, including the development of depressive symptoms.

Multiple ecological domains are salient for low-income, urban African American adolescents, and may impact the development of depressive symptoms in these youth. Life events that occur to the adolescent have been consistently associated with youth’s depressive symptoms (Cardemil et al. 2007; Cicchetti and Toth 1998; Compas et al. 1994; Deardorff et al. 2003; Hankin and Abramson 2001). Given the salience of the family in African American culture (Hammack 2003; Hammack et al. 2004), it is not surprising that research has found that life events within the family are associated with African American youth’s depressive symptoms (e.g., Deardorff et al. 2003; Hammack et al. 2004). Peer relationships are salient during adolescence, and consistent with this developmental trend, research has found an association between peer life events and adolescent depressive symptoms (Berndt 1982; Brown 1990; Deardorff et al. 2003; Larson et al. 1996). Thus, to understand associations between life events and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents, it is important to examine events that happen to the self, to family members, and to peers as each are relevant stressors for African American adolescents and can have implications for depressive symptoms.

Timing of Life Event Stress

In addition to examining the ecological domain in which life events occur, it is important to examine the timing of these events. While there is evidence of some stability in depressive symptoms in youth (for a review see Tram and Cole 2006), research has shown that youth’s depressive symptoms change over time. For example, researchers have estimated that approximately 25% of youth display significant shifts in depressive symptoms during adolescence, with about half of these adolescents showing a decrease in depressive symptoms and half showing an increase in depressive symptoms (DuBois et al. 1995). One possible explanation for these shifts in depressive symptoms is youth’s experience of life event stress. Thus, it is important for researchers to assess when life events occur as well as the impact of life events at different points in development in order to better understand how life events impact both initial levels and changes in youth depressive symptoms.

Longitudinal studies examining the impact of life event stress on the development of depressive symptoms in youth have produced mixed findings (Garber et al. 2002; Ge et al. 1994). For example, research has shown that, for females, initial levels of life event stress (i.e., life events measured at Time 1 of the study) and changes in the rates of life stress are significantly related to initial levels and changes in depressive symptoms (Ge et al. 1994). However, Garber et al. (2002) found that while initial levels of life event stress predicted initial levels of depressive symptoms, they did not predict changes in depressive symptoms (Garber et al. 2002). One possible reason for this discrepancy in findings may be due to the fact that these studies did not examine the domain in which life event stress occurred. It may be that certain types of life events become more salient over time. For example, because peer relationships become more important in adolescence (Berndt 1982; Brown 1990; Larson et al. 1996), peer life events also may become increasingly important for the prediction of depressive symptoms during adolescence. Longitudinal research should examine life events occurring in multiple domains and at multiple time points to examine this possibility. Although some studies have measured adverse life events at multiple time points and/or have modeled change in depressive symptoms (e.g., Ge et al. 1994; Garber et al. 2002; Meadows et al. 2006), these studies have not considered the ecological domain in which these life events occur.

Present Study

Research examining the association between life event stress and adolescents’ depressive symptoms has focused typically on the number of life events experienced, rather than on the ecological domains in which these events occur or how associations between life event stress and depressive symptoms may change with age. However, the ecological contexts in which life event stress occurs as well as when the events occur may be important for understanding depressive symptoms, including what may cause changes in depressive symptoms over time (DuBois et al. 1995; Larson and Ham 1993). Therefore, the present study examines whether life events occurring to youth, their family members, and their peers predict depressive symptoms in adolescence, and whether the strength of associations between these types of events and depressive symptoms change as a function of grade level in a sample of urban, low-income African American youth.

Several hypotheses were examined in the present study. It was hypothesized that there would be a significant association between life events happening to participants and youth depressive symptoms across grade level (i.e., that grade level would not moderate the association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms; hypothesis 1). Given the salience of the family in African American culture (Hammack 2003; Hammack et al. 2004), it was predicted that there would be a significant association between family life events and youth’s depressive symptoms across grade level, specifically that grade level would not moderate the association between family life events and depressive symptoms (hypothesis 2). Because peer relationships become increasingly important during adolescence (Berndt 1982; Brown 1990; Larson et al. 1996), it was expected that the strength of the association between peer life events and youth depressive symptoms would increase as a function of grade level; in other words, it was hypothesized that grade level would moderate the association between peer life events and youth’s depressive symptoms (hypothesis 3). In line with the cost of caring hypothesis, which posits that females may be more likely than males to be distressed by another’s adversity, leading to higher rates of depression in females (Gore et al. 1993; Kessler et al. 1984), it was predicted that the association between peer and family life events and depressive symptoms would be stronger for females than for males (hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants

Participants were 419 middle school students initially assessed in the fall of first grade as part of an evaluation of two school-based preventive interventions targeting early learning and aggressive behavior (Ialongo et al. 1999). The original sample consisted of 678 children and families whom are representative of students entering first grade in nine Baltimore City public elementary schools, and who were recruited for participation in the intervention trials. Classrooms were randomly assigned to one of the intervention conditions or to a control condition, and interventions were provided over the first grade year only. Permission for participation was obtained through written informed consent by at least one guardian and assent by the participating youth. The study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Of the 678 children who participated in the intervention trial in the Fall of 1993, 585 (86.3%) were African American. Approximately 72% (N = 419) of the African American children assessed in first grade had parental consent, verbally assented to complete face-to-face interviews in the 6th grade, and reported about their experiences of adverse life events and depressive symptoms in grades 6, 7, 8 and 9. These 419 youth comprised the sample of interest with 221 (52.8%) males and 198 (47.2%) females. As an indicator of low socioeconomic status, 71.1% of these youth received free or reduced lunch according to parental report. At the sixth grade assessment, the youth ranged in age from 10.63 to 13.12 years (M = 11.77, SD = 0.35). Chi-square tests showed no differences in gender or intervention status between the 419 participants included in this study and the 166 African American children who did not participate in 6th–9th grade assessments (ps >.05), although the two groups differed in lunch status (p <.001) in that more study participants received free or reduced lunch compared to non-participants. The t tests showed no differences between these two groups in terms of age at 6th grade, or the 6th, 7th, 8th or 9th grade study variables, although there was a difference between participants and non-participants in experiences of peer life events in 8th grade; specifically, non-participants experienced more peer life events in 8th grade than study participants. There were no significant differences between the control group and either intervention group for life events happening to participants, family life events, peer life events, or depressive symptoms in 6th–9th grade (ps >0.05). Descriptions of the measures and methods used to assess first grade variables may be found in Ialongo et al. (1999).

Measures

Demographic Information

Participants’ gender, age, race and receipt of free or reduced lunch (as an indicator of socioeconomic status) were collected. Intervention status (i.e., participation in an intervention or control condition during first grade) also was recorded.

Experiences of Adverse Life Events

Adverse life events were assessed using a modified version of the Life Events Questionnaire Adolescent Version (LEQ-C and LEQ-A; adapted from Coddington 1972). The LEQ-A is a self-report checklist of the occurrence of stressful life events occurring in the past year. This measure assesses discrete and identifiable life events. The LEQ-A measure was modified for this study in order to include a broader range of life events relevant to adolescence and family-related stressors by adding items from the Adolescent Perceived Events Scale (APES) (Compas et al. 1985) and the Adolescent-Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes (A-FILE) (McCubbin and Patterson 1983). In addition, the LEQ-A was modified to assess three sets of events including: (1) events experienced directly; (2) events experienced by family members; and (3) events experienced by friends. The wording of the items identified which ecological domain was being assessed; specifically, questions asked whether an event happened to a family member, a peer, or the participant. For example, sample items include “Were you or a family member beaten up this past year?” (coded as self or family life event accordingly) and “Did a close friend have a parent become ill/injured in the past year?” (coded as peer life event). The number of family life events, peer life events and life events happening to participants were summed to create an overall score for life events in each domain. Although the psychometric properties of this modified measure have not been reported, psychometric properties for the component measures are available. Two-week test–retest reliability of the APES for occurrence of events was .85 for young adolescents (ages 12–14) (Compas et al. 1987). Test–retest reliability for the A-FILE is .82 and internal reliability is .69 (Garbarino et al. 1984).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Baltimore How I Feel (BHIF; Ialongo et al. 1999), a 45-item self-report measure of depressive and anxious symptoms. The BHIF was designed to be used as a first stage measure in two-stage epidemiologic investigations of the prevalence of child mood and anxiety disorders as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., rev.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association 1994). Items were drawn from a number of child self-report measures, including the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1983), the Depression Self-Rating Scale (Asarnow and Carlson 1985), the Hopelessness Scale for Children (Kazdin et al. 1986), the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds and Richmond 1985), and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (Spence 1997). For each item, participants reported the frequency of depressive and anxious symptoms over the last 2 weeks using a 4-point scale (0 = Never; 3 = Most times). Summary scores were created by summing the 19 depression items to obtain a BHIF depression subscale score. The internal consistency alphas for the depression subscale ranged from .82 to .87 in 6th through 9th grade, indicating that this is a reliable measure. The BHIF depression subscale was significantly associated with a middle school diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (DISC-IV) (Shaffer et al. 2000), suggesting it has predictive validity.

Data Analytic Strategy

Life events across ecological domains (i.e., life events happening to participants, family life events, peer life events) and depressive symptoms were assessed in each of grades 6–9. These repeated measures of life events and depressive symptoms are nested within each participant. Therefore, multilevel modeling using the SAS PROC MIXED procedure was used to test whether associations between life events and depressive symptoms changed over time. For these analyses, Level 1 of the multilevel model is the repeated measures over time, while Level 2 is the adolescent/individual. Each type of life event (i.e., life events happening to participants, family life events, peer life events) was examined in a separate model. In these models, life events and grade level were the independent variables. Grade level was tested as a moderator of the association between life events and depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms in grades 6–9 were the dependent variables. Because the associations between life events and depressive symptoms may vary by gender, analyses were run separately for males and females.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for study variables by grade level are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The most frequently endorsed life event items in grades 6 and 7 were: (1) “Did a family member have a parent become ill/injured in the past year?” (2) “Did a family member have a sibling become ill/injured during the past year?” (3) “Did a family member have a parent die this past year?” and (4) “Did you see someone beaten up this past year?” In grade 8, the most frequently endorsed life events were: (1) “Did a family member have a parent become ill/injured in the past year?” (2) “Did a family member have a sibling become ill/injured during the past year?” (3) “Did you see someone beaten up this past year?” and (4) “Did a family member have a parent die this past year?” In grade 9, the most frequently endorsed life events were: (1) “Did you see someone beaten up this past year?” (2) “Did a family member have a parent become ill/injured in the past year?” (3) “Did a family member have a sibling become ill/injured during the past year?” and (4) “Did a family member get in trouble with the law during this past year?” Males and females reported similar rates of depressive symptoms in grades 6, 7, and 9, but females reported significantly more depressive symptoms than males in grade 8 (t = −3.80, p <0.001). There were no gender differences in peer life events in grades 6–8. However, results revealed gender differences in 9th grade, with males reporting more experiences of peer life events than females (t = 2.39, p <0.05). There were no gender differences in life events happening to participants or family life events in grades 6–9.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviations of depressive symptoms for total sample and by gender

| Total M (SD) |

Males M (SD) |

Females M (SD) |

t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th grade level | 15.07 (8.89) | 14.97 (8.44) | 15.18 (9.38) | −0.26 |

| 7th grade level | 13.23 (8.44) | 12.61 (7.53) | 13.93 (9.34) | −1.67 |

| 8th grade level | 12.56 (8.41) | 11.40 (7.24) | 13.90 (9.41) | −3.20*** |

| 9th grade level | 12.99 (9.06) | 12.67 (8.91) | 13.36 (9.23) | −0.83 |

p <0.001

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations of life events for total sample and by gender

| Total M (SD) |

Males M (SD) |

Females M (SD) |

t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer life events | ||||

| 6th grade level | 2.69 (2.49) | 2.80 (2.36) | 2.58 (2.61) | 0.94 |

| 7th grade level | 2.28 (2.36) | 2.38 (2.45) | 2.18 (2.25) | 0.90 |

| 8th grade level | 2.42 (2.40) | 2.61 (2.46) | 2.20 (2.31) | 1.83 |

| 9th grade level | 2.20 (2.48) | 2.45 (2.63) | 1.91 (2.27) | 2.39* |

| Participant life eventsa | ||||

| 6th grade level | 3.43 (2.43) | 3.31 (2.33) | 3.57 (2.53) | −1.15 |

| 7th grade level | 3.24 (2.39) | 3.28 (2.48) | 3.21 (2.29) | 0.31 |

| 8th grade level | 3.21 (2.55) | 3.25 (2.59) | 3.15 (2.51) | 0.42 |

| 9th grade level | 2.98 (2.39) | 2.87 (2.35) | 3.11 (2.44) | −1.08 |

| Family life events | ||||

| 6th grade level | 3.44 (2.42) | 3.31 (2.31) | 3.59 (2.52) | −1.28 |

| 7th grade level | 3.24 (2.39) | 3.28 (2.48) | 3.21 (2.29) | 0.31 |

| 8th grade level | 3.21 (2.55) | 3.25 (2.59) | 3.15 (2.51) | 0.42 |

| 9th grade level | 2.98 (2.39) | 2.87 (2.35) | 3.11 (2.44) | −1.08 |

p <.05

Refers to life events happening to participants

Does Grade Level Moderate the Association Between Life Events Happening to Participants and Depressive Symptoms?

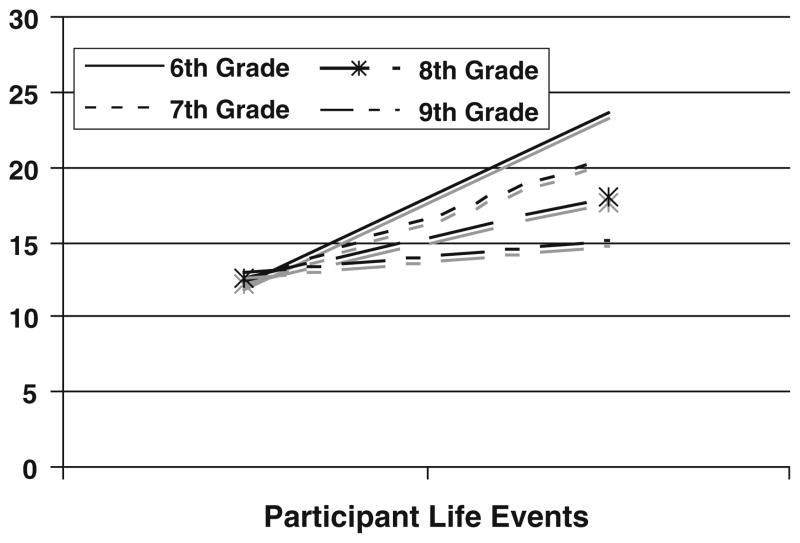

There was a significant positive association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms for females (β = 2.13, p <0.001). However, this association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms was qualified by an interaction with grade level (β = 0.22, p <0.01). As shown in Fig. 1, the strength of the association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms decreased from grades 6–9 for females. For males, there was a significant positive association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms (β = 0.16, p <0.001). The interaction with grade level was not significant (β = 0.11, p >0.05), indicating that the strength of the association between life events happening to participants and depressive symptoms did not vary by grade level for males. Thus, while hypothesis 1 was supported for males, it was not supported for females.

Fig 1.

Association between participant life events and depressive symptoms: Females. “Participant life events” refers to life events happening to participants

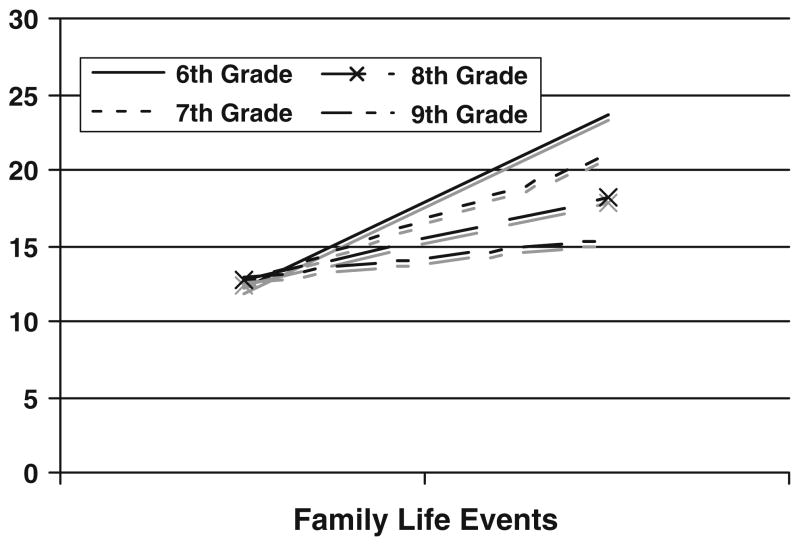

Does Grade Level Moderate the Association Between Family Life Events and Depressive Symptoms?

For females, the significant positive association between family life events and depressive symptoms (β = 2.08, p <0.001) was qualified by a significant interaction with grade level (β = −0.21, p <0.01). As shown in Fig. 2, the strength of the association between family life events and depressive symptoms decreased over time for females. For males, there was a significant positive association between family life events and depressive symptoms (β = 0.16, p <0.001). The interaction between family life events and grade level was not significant for males (β = 0.12, p >0.05), indicating that the strength of the association between family life events and depressive symptoms was similar across grade levels. Thus, while hypothesis 2 was supported for males, it was not supported for females. By visual inspection, the association between family life events and depressive symptoms was stronger for females than males, supporting hypothesis 4.

Fig 2.

Association between family life events and depressive symptoms: Females

Does Grade Level Moderate the Association Between Peer Life Events and Depressive Symptoms?

For females, there was a significant positive association between peer life events and depressive symptoms (β = 0.25, p <0.001). Grade level did not moderate the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms (β = −0.01, p >0.05); the strength of the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms did not significantly vary by grade level for females. For males, there was a significant positive association between peer life events and depressive symptoms (β = 0.29, p <0.001). Grade level did not moderate the positive association between peer life events and depressive symptoms for males (β = −0.03, p >0.05). Thus, hypothesis 3 was not supported for females or males. By visual inspection, the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms was similar for females and males; thus, hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Discussion

Despite recognition that the salience of life events may vary depending on the ecological domain in which they occur (e.g., Leadbeater et al. 1995), much of the existing research has focused on the number of life events experienced rather than the type of life events experienced. The present study examined how life events in three ecological domains, namely life events happening to participants, peer life events, and family life events, impact depressive symptoms in grades 6–9 in a sample of urban, low-income, African American adolescents. Results revealed differences in the predictive utility of life events based on the domain in which these life events occurred and when they occurred. Specifically, peer life events negatively impacted depressive symptoms throughout middle school for males and females, and the strength of the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms was similar across grade levels. The effect of life events happening directly to the participant and their family varied over time for females, while the effect of these life events on depressive symptoms was similar across grade levels for males. Thus, results of this study highlight the importance of examining life events across ecological domains in order to increase our understanding of the development of depressive symptoms in urban, African American youth.

This study examined whether grade moderated the association between three domains of adverse life event stress (life events happening to participants, peer life events, family life events) and depressive symptoms. Results suggest that the importance of experiences of peer life events for depressive symptoms in urban, low-income, African American youth remains consistent during middle school. Although grade level did not moderate the association between peer life events and depressive symptoms, the positive association between peer life events and depressive symptoms was similar throughout grades 6–9 and held regardless of gender. As discussed in the developmental literature, peer relationships are important during adolescence for both males and females (e.g., Larson et al. 1996). During this time in development, adolescents spend much of their time with peers and peer relationships become part of youth’s identities (i.e., I belong to the “in” crowd, I am a “jock”). It may be the case that this increased identification with peers during adolescence has a similar meaning for males and females, and for this reason, peer life events impact youth depression similarly regardless of gender.

Importantly, findings showed gender differences in the impact of family life events and life events happening to participants on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. While the effect of life events happening to participants and family life events remained consistent over time for males, the effects of life events happening to participants and family life events, although still significant, decreased over time for females. It may be that, for females, peer relationships become more salient as they begin to spend much of their time with peers, and life events happening to participants and family life events become less important as compared to peers. According to the “cost of caring” hypothesis, females may be more likely than males to be distressed by another’s adversity (e.g., friends, family), in addition to their own, thus leading to higher rates of depressive symptoms in females (Gore et al. 1993; Kessler et al. 1984). For males, life events happening to participants, peer life events and family life events had similar effects on the development of depressive symptoms over time suggesting that, for males, events involving others, in addition to events directly related to themselves, cause distress in males and impact their depressive symptoms. Counter to prior research documenting simultaneous increases in adverse life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence (e.g., Ge et al. 2001), these data revealed slight decreases in life events and depressive symptoms for males and females from grades 6–9. It may be that these adolescents are reporting less experiences of life event stress because they are habituating to these stressors over time and in turn also experiencing less depressive symptoms. Alternatively, these youth may be responding to distress in ways that are “adaptive” for the setting in which they reside (e.g., externalizing symptoms) rather than responding in ways that may be considered a sign of weakness in the context in which they live (e.g., crying) (Grant et al. 2004; Grant et al. 2005). Findings from this study suggest that life events across ecological domains, specifically life events happening to participants, peer life events, and family life events, impact the development of depressive symptoms in urban, African American youth; this information can be used to design future prevention and intervention efforts.

Implications

Findings from this research suggest that interventions focusing on depressive symptoms in urban, low-income African American youth may be improved by designing targets based on the type of adverse life events experienced. Because peer life events impact depressive symptoms throughout middle school, universal interventions that include adolescents and their peers should help youth learn new ways to manage their distress regarding negative life events occurring to themselves and/or their peers. Findings suggest that a universal intervention approach is warranted given life events of peers are common youth stressors and likely lead to a range in the severity of symptoms depending on how well the youth is able to manage these stressors (e.g., mild to severe depressive symptoms). These interventions could include talking to others, such as peers and parents, to working through solutions for “controllable” peer life events (e.g., If a friend obtains a bad grade, the youth can form a study group including that friend). For peers’ life events that may be more “uncontrollable” (e.g., a peer being a victim of neighborhood violence), youth may benefit from developing a range of coping strategies that help them manage their distress regarding peers’ negative experiences, such as approach coping techniques in which individuals actively confront a problem, including seeking social support. Youth would benefit from learning multiple ways to cope with problems so that they can be well-equipped to face a range of stressful life events and manage their reactions to these events. Having such tools would likely be beneficial for youth displaying varying severity of depressive symptoms.

Because life events happening to participants, peer life events, and family life events predicted depressive symptoms for males and females, clinicians can screen for each of these types of life events. Because African Americans residing in urban settings may experience social and economic marginalization, strong familial support networks are essential to urban, African American youth’s healthy development (Hammack et al. 2004); the family context can serve to ameliorate the negative effects of stressors (Hammack et al. 2004). Given the importance of the family for African American adolescents (Hammack 2003; Hammack et al. 2004), it could be beneficial for intervention strategies to target not only the individual but also the family system (Asarnow et al. 2002; Deardorff et al. 2003; Diamond et al. 2002). For example, interventions can work to increase social support within the family system as well as develop effective communication strategies. By increasing social support and communication within the family system, youth and their families can work together to reduce the impact of certain stressors, such as parental job loss, as well as ventilate negative feelings, or use emotion-focused coping, regarding a common family stressor. These strategies may help youth deal with stressors across ecological domains.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The present study examined the role of life events across ecological domains, including life events happening to participants, peer life events, and family life events, in the development of youth’s depressive symptoms, in contrast to prior research that often has focused only on the number of life events experienced. In addition, the longitudinal design of the present study provides a greater understanding of the changes in youth depressive symptoms that occur in response to life event stress. Finally, this study examined the association between life events and depressive symptoms in urban, low-income, African American youth who, despite disproportionate exposure to adverse life events in multiple ecological domains, do not show elevated depressive symptoms in some research (e.g., Franko et al. 2004).

This study’s strengths should be considered in the context of some limitations. Life events and depressive symptoms were assessed using self-report measures that may be vulnerable to response bias. Future work should use multiple informants, including teacher and parent reports, as they would help corroborate youth’s reports regarding experiences of adverse life events and depressive symptoms. While it should be noted that adolescents are considered better reporters of their own internal experiences, such as depressive symptoms (Weisz et al. 2001), parents and teachers can be reliable reporters of certain depressive symptoms, particularly observable symptoms such as signs of loneliness, withdrawal, somatic complaints, and attention problems, which are likely more severe forms of depressive symptoms (Mesman and Koot 2000); thus, parent and teacher reports of depressive symptoms, in addition to parent and teacher reports of life events, can provide information regarding how life events lead to more severe forms of depression than examined in this research.

While a strength of this study was the examination of the impact of life event stress on depressive symptoms in urban, low-income, African American youth, it remains unclear whether these findings are applicable to African American youth from other backgrounds or youth from other ethnic or racial groups. For example, it may be that the life events of families and peers are more important than those experienced more directly by individuals for understanding depressive symptoms in collectivist cultures, while events directly affecting individuals are more important to individualistic cultures. Future work should examine this possibility, and other ways in which life events across ecological domains impact youth’s depressive symptoms in other ethnic and racial groups and African American youth from other backgrounds. Finally, future work should examine whether there are shifts in the associations between the life events of a participant, peers, and families and depressive symptoms later in development, such as during the transition to late adolescence or emerging adulthood.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children, parents, and teachers who participated in this study. We thank Dr. Philip Wirtz from The George Washington University for his help in the preparation of this paper. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH057005) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11796) to Nicholas Ialongo, and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to Sharon Lambert (5R01MH078995-03).

Biographies

Yadira M. Sanchez is a doctoral student in the Clinical Psychology program in the Department of Psychology at The George Washington University. Her research focuses on the impact of adverse life events on internalizing and externalizing symptoms in urban and ethnic minority youth, youth coping strategies, and early intervention and prevention.

Sharon F. Lambert is an associate professor of Clinical Psychology in the Department of Psychology at The George Washington University. Her research focuses on the etiology, correlates, and course of depressive symptoms in urban and ethnic minority youth, community violence exposure, and school-based prevention.

Nicholas S. Ialongo is a professor in the Department of Mental Health in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Prevention and Early Intervention. His research focuses on the design, implementation, and evaluation of universal preventive interventions to prevent mental health and substance use disorders.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yadira M. Sanchez, Email: ysanchez@gwmail.gwu.edu, Department of Psychology, George Washington University, 2125 G Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA

Sharon F. Lambert, Email: slambert@gwmail.gwu.edu, Department of Psychology, George Washington University, 2125 G Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA

Nicholas S. Ialongo, Email: nialongo@jhsph.edu, Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 624 N. Broadway, 8th Fl., Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

References

- Abela JRZ, Sullivan C. A test of Beck’s cognitive diathesis-stress theory of depression in early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:384–404. doi: 10.1177/0272431603258345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson GA. Depression self-rating scale: Utility with child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(4):491–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Scott CV, Mintz J. A combined cognitive-behavioral family education intervention for depression in children: A treatment development study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26(2):221–229. doi: 10.1023/A:1014573803928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2304_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development. 1982;53(6):1447–1460. doi: 10.2307/1130071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32(7):513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. Peer groups and peer culture. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Reivich KJ, Beevers CG, Seligman MEP, James J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in low-income, minority children: Two-year follow-up. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45(2):313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):221–241. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddington RD. The significance of life events as etiological factors in the diseases of children II: A study of a normal population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1972;16:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(72)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacquez FM, et al. Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A longitudinal investigation of parent and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(1):156–165. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.111.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Davis GE, Forsythe CJ. Characteristics of life events during adolescence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13:677–691. doi: 10.1007/BF00929795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Davis GE, Forsythe CJ, Wagner BM. Assessment of major and daily stressful events during adolescence: The adolescent perceived events scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;4:534–541. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Grant KE, Ey S. Psychosocial stress and child and adolescent depression: Can we be more specific. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 509–523. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Gonzales NA, Sandler IN. Control beliefs as a mediator of the relation between stress and depressive symptoms among inner-city adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(2):205–217. doi: 10.1023/A:1022582410183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Reis BF, Diamond GM, Siqueland L, Issacs L. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: A treatment development study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1190–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Felner RD, Bartels CL, Silverman MM. Stability of self-reported depressive symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 1995;24(4):386–396. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2404_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH, Brown KM, Barton BA, McMahon RP, Schreiber GB, et al. Expanding our understanding of the relationship between negative life events and depressive symptoms in black and white adolescent girls. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1319–1330. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Sebes J, Schellenbach C. Families at risk for destructive parent-child relations in adolescence. Child Development. 1984;55(1):174–183. doi: 10.2307/1129843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):79–95. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(3):404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz F, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(4):467–483. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine R, Colten M. Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1993;3:101–125. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0302_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(3):447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Katz BN, Thomas KJ, O’Koon JH, Meza CM, DiPasquale A, et al. Psychological symptoms affecting low-income urban youth. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:613–632. doi: 10.1177/0743558403260014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, McCormick A, Poindexter L, Simpkins T, Janda CM, Thomas KJ, et al. Exposure to violence and parenting as mediators between poverty and psychological symptoms in urban African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:507–521. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL. Toward a unified theory of depression among urban African American Youth: Integrating socioecologic, cognitive, family stress, and biopsychosocial perspectives. Journal of Black Psychology. 2003;29(2):187–209. doi: 10.1177/0095798403029002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Robinson WL, Crawford I, Li ST. Poverty and depressed mood among urban African-American adolescents: A family stress perspective. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13(3):309–323. doi: 10.1023/B:JCFS.0000022037.59369.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(6):773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Kellam SG, Poduska J. Tech Rep No 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 1999. Manual for the Baltimore how i feel. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, Colbus D. The hopelessness scale for children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:241–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLeod J, Wethington E. The costs of caring: A perspective on the relationship between sex and psychological distress. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory research and applications. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff; 1984. pp. 491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Unpublished manuscript. Pittsburg, PA: University of Pittsburgh; 1983. The children’s depression inventory: A self-rated depression scale for school-age youngsters. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Ham M. Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(1):130–140. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents’ daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM. Gender-linked vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms, stress, and problem behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:1–29. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0501_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. Marriage and Family Review. 1983;6:7–37. doi: 10.1300/J002v06n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO, Brown JS, Elder GH. Depressive symptoms, stress, and support: Gendered trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(1):93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9021-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Koot HM. Child-reported depression and anxiety in preadolescence: I. Associations with parent- and teacher-reported problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(11):1371–1378. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales JR, Guerra NG. Effects of multiple context and cumulative stress on urban children’s adjustment in elementary school. Child Development. 2006;77(4):907–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Ge X, Brody GH, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. African American children’s depressive symptoms: The prospective effects of neighborhood disorder, stressful life events, and parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:163–176. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Posterino M, Carlin JB, Bowes G. Life events and early onset depression: Cause or consequence? Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1203–1210. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised children’s manifest anxiety scale (RCMAS) manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Sobhan M. Symptoms of depression in adolescence: A comparison of Anglo, African and Hispanic Americans. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21(6):639–651. doi: 10.1007/BF01538736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Dulcan M, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):103–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374-424jccp3501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:280–297. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tram JM, Cole DA. A multimethod examination of the stability of depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(4):674–686. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, McCarty CA. Control-related beliefs and depressive symptoms in clinic-referred children and adolescents: Developmental differences and model specificity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):97–109. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]